William Evans-Gordon

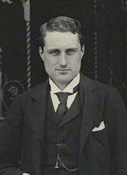

Major Sir William Eden Evans Gordon (8 August 1857 – 31 October 1913)[1] was a British politician, military officer, and diplomat. He was a Member of Parliament (MP) who had served as a military diplomat in India.

As a political officer on secondment from the British Indian Army from 1876 to 1897 during the British Raj, he was attached to the Foreign Department of the Indian Government. His career in India was a mixture of military administrative business on the volatile North-West Frontier, and of diplomacy and foreign policy in advising maharajas or accompanying the viceroy in the princely states.

After leaving the army, Evans Gordon returned to Britain and in 1900 was elected as Conservative Party MP for Stepney on an "anti-alien platform". As a result of the pogroms in Eastern Europe, Jews were arriving in increasing numbers in Britain to stay or en route for America. Evans Gordon, as a "restrictionist", was heavily and actively involved in the passing of the Aliens Act 1905, which sought to limit the number of people allowed to enter Britain even temporarily. He held Stepney from 1900 to 1907.

Early life

[edit]William Eden Evans Gordon was born in Chatham, Kent, the youngest son of Major-General Charles Spalding Evans Gordon (19 September 1813 – 18 January 1901)[2] and his first wife, Catherine Rose (23 July 1815 – 1858),[3] daughter of Rev. Dr. Alexander Rose, D.D., a Presbyterian minister of Inverness.[4][5] William was the youngest of seven children. See also Family life below.

His mother died in 1858, soon after he was born.[6] He was educated at Cheltenham College and entered in October 1870, at the same time as his older brother Charles [Jr.]),[7] and at the Royal Military College, where he was an unattached Sub-Lieutenant on 15 July 1876.[8]

Political career in India

[edit]

Evans-Gordon was commissioned as a second lieutenant into the 67th Foot on 15 January 1877. He transferred on 3 July to the Madras Staff Corps of the Indian Army,[9] attached to the 41st Madras Native Infantry in 1880 as Wing Officer and Quartermaster.[n 1][10] From November 1881 to December 1883 he was extra ADC to the Governor of Madras, M. E. Grant Duff,[9] serving as Wing Officer and Quartermaster in 1883 with the 8th Madras Native Infantry.[11] In 1884, Evans Gordon served under the Foreign Department attached to 1st Regt. Central India Horse (Mayne's Horse) in Guna.[n 2]

During the joint Russo-British Afghan Boundary Commission 1885–1887[12] under Colonel Joseph West Ridgeway, he was busy working as Boundary Settlement Officer and Assistant in charge of Banswara State and Pratapgarh. As an Attaché of the Indian Foreign Department, he worked on translating documents into French and German, apparently for the uniformed but "unofficial" military observers from those countries. He had charge of the Frontier Branch of the Foreign Department and collated the Boundary Commission's documentation.[9][13]

From 1884 to 1888, he was Assistant Secretary during the greater part of the Viceroy Lord Dufferin's tenure by accompanying the Viceroy on his tours and translating at his interviews with Indian princely rulers.[9] In 1885, Evans-Gordon was back with the 8th Madras Regiment in Saugor as Officiating 3rd Class Political Assistant,[14] and the following year, he was attached to the Foreign Department of the Indian Government.[15]

In September 1886, he accompanied the Foreign Secretary of the Indian Government (Sir Mortimer Durand) up the military road being built through the Khyber Pass by Colonel Robert Warburton to the new fort at Landi Kotal.[16] The Durand Line remains the international boundary between Afghanistan and modern-day Pakistan.

On 15 July 1887, Evans-Gordon was promoted to Captain in the Indian Staff Corps, as Assistant Secretary at the Foreign Department from 1888 to 1892.[9][17] As political officer in 1888, he was prominently connected with negotiations for the surrender of Ghazi Ayub Khan, who eight years earlier had defeated a British army at the Battle of Maiwand during the Second Anglo-Afghan War and had laid siege to Khandahar. He sought refuge in Iran, where he entered into negotiations with Sir Mortimer Durand, now ambassador at Teheran. Evans-Gordon took charge of him on his arrival in India and escorted him and his entourage from Karachi to Rawalpindi.[9]

He was appointed Joint-Commissioner in Ladakh in 1889 (where he was described as "an energetic and able officer"),[18] and Assistant Resident in the recently annexed Jammu and Kashmir in November 1890, ruled by Maharaja Pratap Singh. During his Indian furloughs, he travelled in many parts of the East and penetrated some distance into Tibet in 1891. He accomplished a remarkable ride on horseback from Leh to Srinagar, 250 miles, in 33 hours; crossed three passes of the Himalayas at around 13,500 feet.; covered the distance, 152 miles, in 37 hours.[19]

He was a political officer in attendance on the Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad III[n 3] when he travelled to Europe in 1894.[20] In March 1895, he was appointed Officiating Political Resident in Jhalawar State (a subdivision of the Rajputana Agency during the British Raj) Evans-Gordon was promoted Major on 15 July 1896.

In 1896, he was also connected with the deposition of the Maharaja of Jhalawar, Rana Zalim Singh, for which he was criticised in Parliament, but the Secretary of State asserted that the Political Agent had acted with "discretion and tolerance".[21]

He retired on pension on 13 May 1897,[9][20][22] and on 17 February 1900, he was appointed a Major in the Reserve of Officers.[23] he was awarded the Legion of Honour, Reserve of Offs., 4th Class, on 17 February 1900.[9]

The Times of India Illustrated Weekly of 5 September 1906 reported that in Kashmir, at Ladakh and in attendance on the Gaekwar in Europe, he "won the trust and esteem of all the chiefs and magistrates with whom he was brought into relation".[24]

Indian attitudes to Jews

[edit]Unlike in many other parts of the world, Jews have historically lived in India without any instances of anti-Semitism from the local majority populace, the Hindus, but Jews were persecuted by the Portuguese during their control of Goa.[25]

Political career in Britain

[edit]Background

[edit]

The Stepney constituency, one of the poorest districts of London, saw in a rise in immigration during the late 19th century and early 20th century, partially as a result of the anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire[26] As far back as 1889, a House of Commons Committee had concluded that there had been an increase in pauperism in the East End of London by the crowding out of English labour from foreign immigrants.

In July 1894, Lord Rosebery proposed a Bill in the House of Lords designed to reform the current legislation on aliens although it was withdrawn in August 1894 after its second reading.[27] Restrictionism came to be a notable canvassing topic in the 1892 and 1895 general elections,[28] and the recently-succeeded Earl of Hardwicke proposed a similar Aliens Bill in 1898. That year, a year after Evans-Gordon had left the Army, a by-election was held in Stepney after the sudden death of the Tory MP Frederick W. Isaacson.[n 5] Evans-Gordon stood as the Conservative candidate but lost to the Liberal journalist William Charles Steadman by 20 votes.[29]

MP for Stepney

[edit]Evans-Gordon was elected as MP for Stepney on an anti-alien platform in the 1900 general election and held the seat until 1907.[30] Along with the somewhat older Howard Vincent, he was among the first MPs to arouse public opposition to immigration.[31] Although the growing sense of anti-alien feeling found expression in certain localised quarters of the franchised electorate,[32] the primary issues in the 1900 poll were a desire to end the Second Boer War (hence the nickname (khaki election) and the vexed question of home rule for Ireland.[33][34]

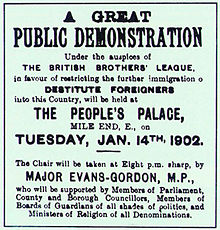

After his election, Evans-Gordon became the brains and driving force behind the British Brothers' League (BBL), an anti-alien pressure group formed in Stepney in May 1901, but he took care to front the League with one William Stanley Shaw, an unimportant City clerk who was its first president.[35][36][37] Howard Vincent (MP for Sheffield Central since 1885) and several East End Conservative MPs (Murray Guthrie, Spencer Charrington and Thomas Dewar) became members of the League.

Evans-Gordon became known as one of the most vocal critics of aliens at the time and commented that "a storm is brewing which, if it is allowed to burst, will have deplorable results".[26][38] Once elected he continued his theme of anti-immigrant rhetoric. He claimed in 1902 that "not a day passes but English families are ruthlessly turned out to make room for foreign invaders. The rates are burdened with the education of thousands of foreign children".[39]

Evans-Gordon and the BBL were instrumental in setting up a Royal Commission on immigration of which he was a member.[40][n 6]

Over a two-month period, Evans-Gordon travelled extensively in Eastern Europe, found out at first hand about the highly-restrictive conditions imposed on Jews in the Pale of Settlement and in Rumania[42][n 7] His book (with map) about his fact-finding mission, The Alien Immigrant, (Evans-Gordon 1903) is an even-handed account of his research. In the first chapter, it highlights the apparent concern of the British Board of Deputies for and sometimes its antipathy toward the refugees from foreign shores.[43] Although it contains some gratuitous low-level antisemitism,[44] the book in general disinterestedly records the situation of the Jews and at one point favourably compares conditions of the poor of Libau to the "horrors of the East End."[45] On the other hand, the conditions of hand-loom workers in Łódź moved him to this description:

The industry is carried on under appalling conditions. I shall never forget the places in which I saw this work being done. It would need the pen of a Zola to describe them. Three or four looms were crammed into one room with as many families. I have never, even in Vilna or the East of London, seen human beings condemned to live in such surroundings. They had the appearance of half-starved consumptives.[46]

The last chapter contains examples of other unwelcome aliens such as organised gangs of German robbers.[n 8] The book was dedicated "To my friend Edward Steinkopff",[n 9] who bought the deep blue St. James's Gazette in 1886.[n 10] The St. James Gazette under its new owner may have been connected with the start of a new anti-alienism movement in the press in 1886.[49]

The book was used in the evidence that he presented to the Aliens Commission in its inquiries and eventually resulted in the Aliens Act 1905, which placed restrictions on Eastern European immigration,[26] but discussion of the Bill in Parliament provoked considerable opposition. Winston Churchill was MP for Manchester North West, where one third of his constituents were Jewish. Like his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, Churchill bucked the trend of widespread antisemitism in the British upper classes and actively opposed the Aliens Bill.[50] In an open letter to Nathan Laski[51] (a prominent member of the Jewish community in his constituency and father of Harold Laski), Churchill quoted a speech by Lord Rothschild, a Liberal supporter and member of the Aliens Commission:

"The Bill introduced into the House of Commons proposes to establish in this country a loathsome system of police interference and espionage, of passports and arbitrary power exercised by police officers who in all probability will not understand the language of those upon whom they are called to sit in judgement. This is all contrary to the recommendations proposed by the Royal Commission. [...] The whole bill looks like an attempt on the part of the Government to gratify a small but noisy section of their own supporters and to purchase a little popularity in the constituencies by dealing harshly with a number of unfortunate aliens who have no votes."[52]

A committed Zionist, Churchill crossed the floor of the House of Commons on the day the letter appeared.[n 11]

Despite the repeated denials of Arnold White and Evans-Gordon, anti-Semitism was a central element of the campaign for the Aliens Bill 1900–1905.[53][54][36] The indigent refugees from Russia, Rumania and Poland had further defenders in Parliament, such as Sir Charles Trevelyan, 3rd Baronet, Liberal MP for Elland who, speaking against the Aliens Bill in 1904, said:

"Among many people already—not many in this House, but many people outside of it – there is a frankly anti-Semitic movement, and I deplore it. I believe this is an evil step in the same direction as the Governments of Russia and Rumania have been going. It may be that it is not intended, but the action of many Members of this House has been calculated to excite the feeling which we know to exist in part of our population, and with the case of the persecution of Dreyfus reverberating through the West of Europe there is no use saying that there is no danger of this kind in our own country. I think it is a fortunate thing that we have been peculiarly free from any anti-Semitic movement in England, and we have not lost by it. We have had statesmen, manufacturers, merchants, and the like who themselves, or their predecessors, came to this country as aliens exactly as do those people you now wish to exclude. It seems to me a useless and short-sighted, and at this moment very largely an inhuman policy, to keep out those who may, after all, be like those of whom I have just spoken".[55]

In his 1905 election address, Evans-Gordon laid stress on the recently passed Aliens Act, which he had been greatly instrumental in carrying. He proceeds to explain his position with regard to the Jews.

"It has been falsely asserted that the Aliens Act is aimed against the Jewish people, and that I have been actuated by anti-Semitism. I will not stoop to repudiate such charges. No man views with greater horror and indignation than I the recent barbarous and indescribable massacres of Jews in Russia. But in expressing my deep sympathy with the victims of this most terrible persecution I am bound to repeat my conviction that the solution of the Jewish problem in Eastern Europe will not and cannot be found in the transference of thousands of poverty-stricken and helpless aliens to the most crowded quarters and overstocked markets of our greatest cities. It will be found in the statesmanlike scheme of the Jewish Territorialist Organization for the inauguration of which we are indebted to the genius and patriotism of Mr. Israel Zangwill."[56]

Vincent and Evans-Gordon successfully "stampeded their party into introducing laws to keep the foreigner out".[57] Although a section of the Conservative Party had managed to persuade the Commons to pass anti-Jewish legislation, the Liberals only six months later had a landslide election victory in 1906. Although the Aliens Act was not repealed by the incoming Liberal government, the law was not strictly enforced.[36] Evans-Gordon held on to his seat during the general Conservative defeat and continued to campaign for further anti-immigration legislation. In his successful bid for re-election in 1906, he spoke against the Sinti (German Gypsies) who were trying to settle in England,[58] and, borrowing the slogan of the BBL, he campaigned with the slogan "England for the English and Major Gordon for Stepney".[59]

However, Evans-Gordon's anti-Semitism has been questioned, as he was a supporter of Zionism and kept up regular correspondence with Chaim Weizmann, who would later write of him:

I think our people were rather hard on him. The Aliens Bill in England and the movement which grew around it were natural phenomenon which might have been foreseen.... Sir William Evans-Gordon had no particular anti-Jewish prejudices... he was sincerely ready to encourage any settlement of Jews almost anywhere in the British Empire but he failed to see why the ghettoes of London or Leeds should be made into a branch of the ghettoes of Warsaw and Pinsk.... Sir William Evans-Gordon gave me some insight into the psychology of the settled citizen. [60]

Evans-Gordon received a knighthood in 1905.[61]

Other parliamentary business

[edit]Pilotage Bill 1903

[edit]Evans-Gordon was one of the sponsors of the Pilotage Bill 1903, which dealt with Pilotage Certificates.[n 12] Although the bill was read a second time in May 1906, it was withdrawn.[62]

Anglo-French Festival 1905

[edit]During the Anglo-French Festival 1904 to celebrate the Entente Cordiale, Evans-Gordon apparently proposed an unprecedented multiple joint gathering in Westminster Hall, London, in August.[63]

Later life

[edit]On 1 May 1907, Evans Gordon resigned from the Commons and retired from politics by becoming a steward of the Chiltern Hundreds.

He died suddenly on 31 October 1913 (aged 56) at his home at 4 Chelsea Embankment, London.[1] A notice of his memorial service appeared in The Times.[64]

He was the owner of a 24 hp Thornycroft Phaeton, delivered on 1 June 1906.[65][66]

He was a member of several clubs: Carlton, Boodle's, Naval & Military and Orleans.

Family life

[edit]In 1892 Captain William Evans Gordon married Julia Charlotte Sophia Stewart (b. 21 June 1846) (Julia, Marchioness of Tweeddale),[67] daughter of Lt.-Colonel Keith William Stewart Mackenzie (9 May 1818 – ? June 1881)[n 13] and of Hannah Charlotte Hope Vere.[n 14]

Julia was previously twice married: firstly (as his second wife, on 8 October 1873) to the Right Hon. Arthur Hay, 9th Marquess of Tweeddale, d. 1878; without issue.[69] Secondly, in 1887 she married (as his second wife), the Right Hon. Sir John Rose, 1st Baronet, GCMG, of Queensgate, London, who died in 1888; without issue. Her third marriage to William Evans Gordon was also without issue.[70]

Julia was the sister of James Stewart-Mackenzie, 1st Baron Seaforth, who fought with the 9th Lancers during the Second Anglo-Afghan War of 1878–1880 (later Colonel of the regiment), and was later military secretary to M. E. Grant Duff. He married the daughter of Edward Steinkopff, owner of the St James's Gazette and dedicatee of Evans-Gordon's The Alien Immigrant.[71] Julia and James had one further sibling, Mary Jeune, Baroness St Helier, society hostess and politician.[72]

Evans-Gordon's siblings included:

- Henry (1842–1909), a stockbroker in London; married to Mary Sartoris, daughter of Edward Sartoris MP.

- Jessica (1852–1887), who married Thomas Gibson Bowles MP.

Evans-Gordon's paternal grandfather was Col. George Evans (d.1819), whose principal service in the Napoleonic wars was with the Royal African Corps.[73]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The British Raj, an essentially-military operation, needed a sizable administrative staff. The Madras Staff Corps was a branch of the Indian Staff Corps, itself a department of the Foreign Department of the Indian Government.

- ^ The regiment's CO was the ex officio British Political Officer for a number of small states previously administered by Gwalior Residency.

- ^ The barely audible pronunciation of the final 'd' in 'Gaekwad' was lost on the tone-deaf Britishers, who called the rulers of Baroda the 'Gaekwar'.

- ^ NB may belong somewhere else... The term "Tommy Dodd" (used by Hardwicke's close friends) is variously defined as:

- Hotten's Slang Dictionary; "Tommy Dodd," a game of or pitch and toss. For cheating the unwary at this game, a "Gray" is often used, a halfpenny, with either two "heads" or two "tails"—both sides alike. They are often "rung in" with a victim's own money[182], so that the caller of "heads" or "tails" cannot lose. Thus if A has to call, he or a confederate manages to mix the selected Grays with B's tossing halfpence. There are various and almost obvious uses for Grays.

- Tommy Dodd, Brewers' Dictionary; The "odd" man who, in tossing up as above, either wins or loses according to agreement with his confederate. There is a music-hall song so called, in which Tommy Dodd is the "knowing one."

- A(nother?) rendition of a song "Tommy Dodd" The Saturday Evening Mail, Vol. 3, #23, 7 December 1872;

- 19th-century Cockney rhyming slang for 'sod' or sodomite. Slang pages

- Memories and Base Details by Lady Angela Forbes, p. 65

- Anecdote about Hardwicke's hunting alter ego from Badminton magazine

- ^ "Other London Conservatives were self-made entrepreneurs, such as the Stepney MP F. W. Isaaacson (Con.), who had made his fortune in the silk and coal trades [...] the cost and all-consuming demands of metropolitan representation could be prohibitive to all but the wealthiest candidates". The Newington West Liberal MP noted "the great difficulty in obtaining suitable candidates for London constituencies, owing to the perpetual tax upon their time and pockets".(Windscheffel 2007, p. 112).

- ^ "Now know ye, that We, reposing great trust and confidence in your knowledge and ability, have authorized and appointed, and do by these presents authorize and appoint, you the said Henry, Baron James of Hereford; Nathaniel Mayer, Baron Rothschild; Alfred Lyttelton; Sir Kenelm Edward Digby; William Eden Evans-Gordon; Henry Norman [who uncovered the truth on the Alfred Dreyfus affair]; and William Vallance [clerk to the Whitechapel Board of Guardians][41] to be Our Commissioners for the purposes of the said inquiry." London Gazette, date pls?

- ^ (Evans-Gordon 1903, pp. 48ff). His itinerary took him to Saint Petersburg in Russia; Dvinsk, Riga, Liepāja (Libau), Vilnius and Pinsk in Latvia; Warsaw, Łódź and Kraków in Poland; Galicia (which belonged to Austria); Bucharest, Galați (Galatz) and Lemberg in Rumania; and Berlin and boat from Hamburg.

- ^ Another book published in 1903 amid a growing general anti-German feeling was the spy novel The Riddle of the Sands, by Erskine Childers. (Monaghan 2013, p. 27)

- ^ Edward Steinkopff made a considerable fortune (in excess of £1,500,000 in 1897 from the sale of the Apollinaris mineral water company to the hotelier Frederick Gordon.[47] Steinkopff founded Apollinaris after a suggestion by Ernest Hart, the editor of the British Medical Journal, to George Murray Smith of Smith, Elder & Co. previous owner of the Pall Mall Gazette (out of which the St. James's Gazette was created.)[48] Frederick Gordon was possibly not related to William Evans-Gordon.

- ^ The suddenly Liberal Pall Mall Gazette (whose former owner George Smith was in business with Steinkopff, owner of the St James's Gazette), was previously owned and funded by Henry Hucks Gibbs (later Baron Aldenham) of Gibbs, Bright and Co. of Bristol and Liverpool. The firm of slave traders and owners of sugar plantations in the West Indies cannot possibly have been unknown to William Evans-Gordon's brother George, a partner in § Gladstone, Wyllie & Co. of Calcutta, whose parent company in Liverpool was engaged in the very same trade.

- ^ For more details of this period see WinstonChurchill.org and Hyam, Ronald (1968). Elgin and Churchill at the Colonial Office 1905–1908. London and New York: Macmillan (UK) and St. Martin's Press (US).

- ^ "Boatmen's Association.

News and Notes.

By Julius.

We are pleased to be in a position to state that, persistent rumours to the contrary notwithstanding, Major Evans Gordon still retains his generous interest in our case, and it is very probable that by the time these notes appear the question will have again been raised in Parliament.Customs Journal, 29 May 1905, No. 30. - ^ Julia's father, Keith Mackenzie was a lieutenant in the 90th Regiment; subsequently Major and CO, Ross-shire Highland Rifle Volunteers (1st Volunteer Bn. Seaforth Highlanders).[68]

- ^ Hannah was the daughter of James Joseph Hope Vere, MP, of Craigie Hall and Blackwood, Midlothian (and grandson of Charles Hope-Weir), and of Lady Elizabeth Hay, daughter of the 7th Marquess of Tweeddale.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b The Times, 3 November 1913 p. 11d

- ^ Skelton & Bulloch 1912, p. 394.

- ^ "Catherine Rose, 23 Jul 1815, in 'Alexander Rose'". Scotland, Births and Baptisms, 1564–1950 (index). FHL microfilm 990,667, 990,668, 990,669. FamilySearch. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Scott 1926, pp. 462–3.

- ^ Rose 1835, p. 3.

- ^ He may possibly have lived in Dublin, where his father was Town Major from 1864, and where his father re-married in 1866.

- ^ Cheltenham College Register 1841–1889, p. 277, pdf p. 319

- ^ Hart, H. G (ed.) The New Annual Army List, Militia List, and Indian Civil Service List, 1877, p. 112. London: John Murray. NB His name here is hyphenated..

- For the militarily curious: among other unattached sub-lieutenants at Sandhurst that year were: J.B. De la Poer Beresford, 8th Marquess of Waterford; Walter Kitchener; Aldred Lumley, 10th Earl of Scarbrough; Horace G. Proctor-Beauchamp, 6th Baronet; Frederick W.R. Ricketts, 5th Baronet; (later General) Horace Smith-Dorrien; Richard Garnons Williams; Sir Herbert Williams-Wynn, 7th Baronet; H.C. Wylly, et al.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Skelton & Bulloch 1912, p. 395.

- ^ The New Annual Army List, Militia List, and Indian Civil Service List, 1880. London: John Murray, p. 502

- ^ The New Annual Army List, Militia List, and Indian Civil Service List, 1883. London: John Murray, p. 497 (pdf p. 481).

- ^ See, for example, Ballard 1996, pp. 406–415 and Yate 1888.

- ^ Photographs taken 1885-7 during the desert journeys of the Commission."Collections – Afghan Boundary Commission 1885–1887". Phototheca Afghanica. Foundation Bibliotheca Afghanica. 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ^ The New Annual Army List, Militia List, and Indian Civil Service List, 1885. London: John Murray, p. 497 (pdf p. 501).

- ^ The New Annual Army List, Militia List, and Indian Civil Service List, 1886. London: John Murray, p. 497 (pdf p. 505)

- ^ Warburton 1900, p. 165 See also photograph of Landi Kotal, p. 184.

- ^ Fox-Davies 1905, p. 450.

- ^ "The present Joint-Commissioner in Ladakh is Captain Evans Gordon, an energetic and able officer, as are most of those appointed by the Indian Government to this unsettled and peculiarly situated State. He had not yet arrived at Leh, as his presence had been required at Srinagar; so we were unfortunate in not meeting him here". (Knight 1893, p. 179)

- ^ The Times, 11 November 1891, cited in Skelton & Bulloch 1912, p. 395

- ^ a b India List 1905, p. 489.

- ^ Commons Sitting, 21 July 1896 HC Deb 21 July 1896 vol 43 cc277-92

- ^ "Indian Service Gossip". The Colonies and India. London: 13. 12 June 1897.

- ^ "No. 27165". The London Gazette. 16 February 1900. p. 1078.

- ^ Hansard – Parliamentary Debates, vol. 43, 277–92.

- ^ "When the Portuguese arrived in 1498, they brought a spirit of intolerance utterly alien to India. They soon established an Office of Inquisition at Goa, and at their hands Indian Jews experienced the only instance of antisemitism ever to occur in Indian soil."(Katz 2000, p. 26)

- ^ a b c "Leaving the Homeland". Moving Here. The National Archives (UK). Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Monaghan 2013, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Cesarani 1993, p. 29.

- ^ Liberal Year Book 1905, pp. 302–3.

- ^ Dod's peerage, baronetage and knightage of Great Britain and Ireland for 1908

- ^ Foot 1965, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Some women first got the vote in 1918, and only in 1928 were all females over 21 enfranchised.

- ^ Cesarani 1993, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Politics in 1901. 1901 Census. National Archives. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ^ Bloom 2004, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Field 1993, pp. 302–3.

- ^ The BBL can be viewed as part of a wider effort of certain elements in the Conservative Party to build a base of popular support in the East End and thus drive a wedge between Liberal and labour.(Field 1993, pp. 302–3)

- ^ D. Rosenberg, 'Immigration'

- ^ 'Dispersing the Myths about Asylum' Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine from the Socialist Review

- ^ Harrison 1995.

- ^ Stepney Board of Guardians. AIM25. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ Evans-Gordon 1903, pp. 163–192.

- ^ Evans-Gordon 1903, pp. 2–4.

- ^ Evans-Gordon 1903, pp. 77, 157.

- ^ Evans-Gordon 1903, p. 105.

- ^ Evans-Gordon 1903, p. 145.

- ^ Frederick Gordon at Stanmore Tourist Board.

- ^ Dasent, Arthur Irwin. Piccadilly in three centuries, with some account of Berkeley square and the Haymarket, pp 255–6.

- ^ That is mentioned in passing in Cesarani 1993, p. 29.

- ^ Lyons, Justin D. (Winter 2009). "Churchill and the Jews: A Lifelong Friendship by Martin Gilbert". Shofar (Review). 27 (2). Purdue University Press: 174–176. doi:10.1353/sho.0.0243. JSTOR 42944469. S2CID 144711005.

- ^ "Mr. Churchill and the Aliens Bill". The Times. 31 May 1904. p. 10.

- ^ The Times & 31 May 1904.

- ^ Bloom 2004, pp. 2–5.

- ^ Johnson 2013, p. 2.

- ^ HC Deb 25 April 1904 vol 133 cc1062-131

- ^ The Standard (London), 27 December 1905, p. 6. The ITO came about through Zangwill's response to the Kishinev Pogrom.

- ^ Foot 1965, p. 141.

- ^ Clark 2001, p. 96.

- ^ Monaghan 2013, p. vi.

- ^ Weizmann 1949, pp. 90–92

- ^ Whitehall, 18 December 1905. The KING was also pleased this day to confer the honour of Knighthood upon:— [...] Major William Eden Evans-Gordon, M.P., 4, Chelsea-embankment, S.W. The London Gazette, 19 December 1915

- ^ See Hansard, Pilotage Bill

- ^ Journal des débats, 14 August 1905, p. 1] (in French)

- ^ The Times, 10 November 1913, p. 11b

- ^ No 516 Mapplebeck Stuart & Co. 24 hp Phaeton, works #2441 delivered 1 June 1906 to Sir William Evans Gordon. Thornycroft vehicle register. Thornycroft. Hampshire Cultural Trust. Retrieved 7 July 2019

- ^ Info on the Thornycroft 1905 24hp Phaeton with picture. Thornycroft cars 1905. Thornycroft. Hampshire County Council. Retrieved 8 March 2015

- ^ Keith William Stewart at Geneall.net

- ^ Grierson, James Moncrieff (1909). Records of the Scottish volunteer force, 1859–1908. Edinburgh, London: W. Blackwood and sons. p. 278. (with colour plates)

- ^ Julia's mother was the daughter of the 7th Marquess. Source: Hannah Charlotte Hope-Vere at Geneall.net

- ^ History of the Mackenzies by Alexander Mackenzie, 1894

- ^ Evans-Gordon 1903, p. v.

- ^ Reynolds, K. D. (2016). "Jeune [née Stewart-Mackenzie other married name Stanley], (Susan Elizabeth) Mary, Lady St Helier (1845–1931), hostess". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/51948. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 31 May 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ PRO Kew, file WO 12.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baines, Thomas (1852). History of the commerce and town of Liverpool, and of the rise of the manufacturing industry in the adjoining counties, Vol. II. London: Longman, Brown, Green; Liverpool: The author.

- Ballard, Daniel (1996). "Boundaries: iii. Boundaries of Afghanistan". Encyclopaedia Iranica, IV/3. Online edition. New York: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. pp. 406–415. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- Bloom, Cecil (2004). "Arnold White and Sir William Evans-Gordon: their involvement in immigration in late-Victorian and Edwardian Britain". Jewish Historical Studies. 39. Jewish Historical Society of England: 153–166. JSTOR 29780074.

- Cesarani, David (1993). "An Alien Concept? The concept of Anti-Alienism in British society before 1940". In Cesarani, David; Kushner, Tony (eds.). The Internment of Aliens in Twentieth Century Britain. Routledge. ISBN 9781136293641.

- Clark, Colin R. (October 2001). 'Invisible Lives': the Gypsies and Travellers of Britain (PDF) (Thesis). University of Edinburgh.

- Evans-Gordon, William (1903). The Alien immigrant. London: William Heinemann.

- Fairbairn, James (1905). Fox-Davies, Arthur C. (ed.). Fairbairn's Book of Crests of the Families of Great Britain and Ireland, 4th edition, Vol. I. London: T.C. & E. C. Jack.

- Field, Geoffrey G. (1993). Strauss, Herbert A. (ed.). Hostages of Modernization Volume 1: Germany – Great Britain – France. Current Research on Antisemitism. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110855616.

- Foot, Paul (1965). Immigration and Race in British Politics. Penguin Books.

- Fox-Davies, Arthur C., ed. (1905). Armorial Families: A Directory of Gentlemen of Coat-Armour, 5th edition. Edinburgh: T.C. & E.C. Jack.

- Harrison, Elaine, ed. (1995). "List of commissions and officials: 1900–1909 (nos. 103–145)". Office-Holders in Modern Britain: Volume 10, Officials of Royal Commissions of Inquiry 1870–1939. University of London. pp. 42–57. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- The India List and India Office List for 1905. London: Harrison & Son. 1905.

- Johnson, Sam (2013). "A veritable Janus at the Gates of Jewry. British Jews and Mr Arnold White". Patterns of Prejudice. 47 (1). published online 19 October 2012: 41–68. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2012.735130.

- Katz, Nathan (2000). Who are the Jews of India?. The S. Mark Taper Foundation imprint in Jewish studies. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21323-4.

- Knight, E. F. (1893). Where Three Empires Meet. London: Longman Green & Co.

- The Liberal Year Book for 1905. London: The Liberal Publication Dept. (in association with the National Liberal Federation and the Liberal Central Association). 1905.

- MacGregor, Gordon (2014). "Stirling of Kippendavie". The Red Book of Perthshire. ISBN 0-954-56282-8.

- Monaghan, Casey (2013). England For the English! Anti-Alienism and German Internment in England 1870–1918 (PDF) (Thesis). Brandeis University.

- Pellew, Jill (June 1989). The Home Office and the Aliens Act 1905, Historical Journal, vol. 32, no. 2, June 1989, p. 369-85.

- Rose, Alexander (1835). "Parish of Inverness". The New Statistical Account of Scotland, No. 6 – Inverness and Berwick.

- Scott, Hew (1926). Fasti ecclesiæ scoticanæ; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation, Volume VI. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

- Skelton, Constance Oliver and Bulloch, John Malcolm (1912). Gordons under Arms: A Biographical Muster Roll of Officers named Gordon in the Navies and Armies of Britain, Europe, America and in the Jacobite Risings. Aberdeen University Studies No. 59. Aberdeen: Printed for the University.

- Warburton, Robert (1900). Eighteen Years in the Khyber 1879–1898. London: John Murray.

- Weeden, Edward St. Clair (1911). A year with the Gaekwar of Baroda. Boston: Dana Estes & Co.

- Weizmann, Chaim (1949). Trial and Error. New York: Harper.

- Windscheffel, Alex (2007). Popular Conservatism in Imperial London, 1868–1906. Volume 57 of Royal Historical Society studies in history, New series. Royal Historical Society (Great Britain); Boydell Press. ISBN 9780861932887. ISSN 0269-2244.

- Yate, C. E. (1888). Northern Afghanistan, or Letters from the Afghan Boundary Commission. Edinburgh & London: William Blackwood & Sons.

External links

[edit]- 1857 births

- 1913 deaths

- Military personnel from Kent

- 19th-century British military personnel

- 19th-century British Army personnel

- Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies

- 67th Regiment of Foot officers

- UK MPs 1900–1906

- UK MPs 1906–1910

- Kemble family

- Indian Staff Corps officers

- Madras Staff Corps officers

- British far-right politicians

- Knights Bachelor

- Commanders of the Legion of Honour

- Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

- People from Chatham, Kent

- People educated at Cheltenham College

- Indian Political Service officers

- British people in colonial India

- Antisemitism in the United Kingdom