Historical criticism

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

Historical criticism (also known as the historical-critical method (HCM) or higher criticism,[1] in contrast to lower criticism or textual criticism[2]) is a branch of criticism that investigates the origins of ancient texts to understand "the world behind the text"[3] and emphasizes a process that "delays any assessment of scripture's truth and relevance until after the act of interpretation has been carried out".[4] While often discussed in terms of ancient Jewish, Christian, and increasingly Islamic writings, historical criticism has also been applied to other religious and secular writings from various parts of the world and periods of history.[5]

The historian applying historical criticism has several goals in mind. One is to understand what the text itself is saying in the context of its own time and place, and as it would have been intended to and received by its original audience (sometimes called the sensus literalis sive historicus, i.e. the "historical sense" or the "intended sense" of the meaning of the text). The historian also seeks to understand the credibility and reliability of the sources in question, understanding sources as akin to witnesses to the past as opposed to straightforward narrations of it. In this process, it is important to understand the intentions, motivations, biases, prejudices, internal consistency, and even the truthfulness of the sources being studied. Involuntary witnesses that did not intend to transmit a piece of information or present it to an external audience, but end up doing so nonetheless, are considered greatly valuable. All possible explanations must be considered by the historian, and data and argumentation must be used in order to rule out various options.[6] In the context of biblical studies, an appeal to canonical texts is insufficient to settle what actually happened in biblical history. A critical inspection of the canon, as well as extra-biblical literature, archaeology, and all other available sources, is also needed.[7] Likewise, a "hermeneutical autonomy" of the text must be respected, insofar as the meaning of the text should be found within it as opposed to being imported into it, whether that is from one's conclusions, presuppositions, or something else.[8]

The beginnings of historical criticism are often associated with the Age of Enlightenment, but it is more appropriately related to the Renaissance.[9] Historical criticism began in the 17th century and gained popular recognition in the 19th and 20th centuries. The perspective of the early historical critic was influenced by the rejection of traditional interpretations that came about with the Protestant Reformation. With each passing century, historical criticism became refined into various methodologies used today: philology, textual criticism, literary criticism, source criticism, form criticism, redaction criticism, tradition criticism, canonical criticism, and related methodologies.[10]

Definition

[edit]Historical-critical methods are the specific procedures[3] used to examine the text's historical origins, such as the time and place in which the text was written, its sources, and the events, dates, persons, places, things, and customs that are mentioned or implied in the text.[11] Investigations using the historical-critical method are open to being challenged and re-examined by other scholars, and so some conclusions may be probable or more likely than others, but not certain.[12] This, nevertheless, enables a field to be self-correcting, as mistakes in earlier work can be corrected in subsequent work, and some have argued that this clarifies the level of confidence that someone today is capable of attaining when it comes to what happened in the past.[13]

Critical approaches

[edit]The sense of the historical-critical method involves an application of both a critical and a historical reading of a text. To read a text critically

means to suspend inherited presuppositions about its origin, transmission, and meaning, and to assess their adequacy in the light of a close reading of that text itself as well as other relevant sources ... This is not to say that scripture should conversely be assumed to be false and mortal, but it does open up the very real possibility that an interpreter may find scripture to contain statements that are, by his own standards, false, inconsistent, or trivial. Hence, a fully critical approach to the Bible, or to the Qur’an for that matter, is equivalent to the demand, frequently reiterated by Biblical scholars from the eighteenth century onwards, that the Bible is to be interpreted in the same manner as any other text.[4]

Historical approaches

[edit]By contrast, to read a text historically would mean to

require the meanings ascribed to it to have been humanly 'thinkable' or 'sayable' within the text's original historical environment, as far as the latter can be retrospectively reconstructed. At least for the mainstream of historical-critical scholarship, the notion of possibility underlying the words 'thinkable' and 'sayable' is informed by the principle of historical analogy – the assumption that past periods of history were constrained by the same natural laws as the present age, that the moral and intellectual abilities of human agents in the past were not radically different from ours, and that the behaviour of past agents, like that of contemporary ones, is at least partly explicable by recourse to certain social and economic factors.[4]

Role of methodological naturalism

[edit]Historical phenomena are accepted to be interrelated in a cause-and-effect relationship, and therefore modifications in putative causes will correlate to modifications in putative effects. In this context, an approach called historicism may be applied, where the historical interpretation of cause-and-effect relationships takes place under the framework of methodological naturalism. Methodological naturalism is an approach taken from the natural sciences that excludes supernatural or transcendental hypotheses from consideration as hypotheses. Nevertheless, the historical-critical method can also be pursued independently of methodological naturalism. Approaches that do not methodologically exclude supernatural causes may still take issue with instances of their use as hypotheses, as such hypotheses can take on the form of a deus ex machina or simply involve special pleading in the favor of a religious position. Likewise, present experience suggests that known events are associated with natural causes, and this in turn increases the weight of natural explanations for phenomena in the past when they are competed with supernatural explanations.[14][15] Therefore, without being excluded, natural explanations may still be favored due to their being more in line with the regular scientific and historical understanding of reality.[16]

Methods

[edit]

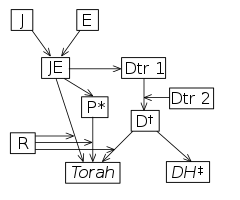

| * | includes most of Leviticus |

| † | includes most of Deuteronomy |

| ‡ | "Deuteronomic history": Joshua, Judges, 1 & 2 Samuel, 1 & 2 Kings |

Historical criticism comprises several disciplines, including[11] textual criticism, source criticism, form criticism, redaction criticism, tradition criticism, and radical criticism.

Textual criticism

[edit]Textual criticism seeks to reconstruct the original form of a text. This is often a prerequisite for the application of downstream critical methods, as some confidence in what the text originally said is needed before dissecting it for its sources, form, and editorial history.[17] The challenge of textual criticism is that the original manuscripts (autographs) of the texts of the Bible have not survived, and that the copies of them (manuscripts) are not identical (as they contain variants). Variants range from spelling mistakes, to accidental omissions of words, to (albeit more rarely) more substantial variants such as those involved in the ending of Mark 16 and the Johannine Comma. The task of the textual critic is to compare all the variants and establish which reading is the original.[18]

Source criticism

[edit]Source criticism is the search for the original sources which lie behind a given text. Source criticism focuses on textual or written sources, whereas the consideration of oral sources lies in the domain of form criticism. A prominent example of source criticism in the study of the Old Testament is the Documentary Hypothesis, a theory proposed to explain the origins of the Pentateuch in five earlier written sources denoted J, E, P, and D. Source criticism also figures in attempts to resolve the Synoptic problem, which concerns the textual relationships between the Gospel of Mark, the Gospel of Matthew, and the Gospel of Luke, as well as hypothetical documents like the Q source.[19] In recent years, source-critical approaches have been increasingly applied in Quranic studies.[20]

Form criticism

[edit]Form criticism is the identification and analysis of "forms" in a text, defined by the use of recognizable and conventional patterns. For example, letters, court archives, hymns, parables, sports reports, wedding announcements, and so forth are recognizable by their use of standardized formulae and stylized phrases. In the Old Testament, prophetic forms are typically introduced by the formula "Thus says the Lord". Many sayings of Jesus have a recognizable formulaic structure, including the Beatitudes and the woe pronouncements upon the Pharisees. Form critics are especially interested in (1) the genre of a text, such as 'letter', 'parable', etc (2) Sitz im leben ("setting in life") referring to the real-life contexts or settings (be they cultural, social, or religious) in which particular forms or language is employed, and (3) oral prehistory of forms, which tend to be short and stereotypical, and so easy to memorize and pass on to others, and their (4) history of transmission.[21]

Redaction and composition criticism

[edit]Redaction criticism studies "the collection, arrangement, editing and modification of sources" and is frequently used to reconstruct the community and purposes of the authors of the text.[22] Whereas source and form criticism are concerned with the units out of which the text originated, redaction criticism shifts the focus to how the author has, by the time of the final composition of the text, modified earlier forms of the text. This editing process of the text is called redaction, and the author redacting the text is called the redactor (or editor). The redactor may be the same figure as the original author. Instances of redaction may cover "the selection of material, the editorial links, summaries and comments, expansions, additions, and clarifications" on the part of the redactor. Redaction criticism can become complicated when multiple redactors are involved, especially over the course of time, producing an iteration of stages or recensions of the text. An investigation of such a process can rely on internal features of the text and, when available, parallel texts, such as between the Books of Kings and the Books of Chronicles.[23] With the progression of scholarship, some have begun to distinguish redaction criticism into redaction criticism and composition criticism. Composition criticism more strictly focuses on the final stages of the redaction of a text, in which the various materials are brought together and fused into a unified whole, and whence the author has imposed a coherent narrative onto the text. The more coherent the final structure is, the more of a "composition" it is, whereas the less coherent the material has been welded, the more it should be seen as a "redaction". Nevertheless, there is no precise boundary in which a text can be said to have moved from a redaction to a composition. Another difference between the two is that redaction criticism is diachronic, looking at the development of the layers of the text through time, whereas composition criticism is synchronic, focusing on the structure of the final text.[24]

Controversy

[edit]Terminology

[edit]"Historical"

[edit]Controversy has emerged emerged regarding terms "historical" and "critical" in the historical-critical method. Two concerns exist surrounding "historical": (1) Critical approaches are not only historical but also literary and (2) The word "history" is too broad. It can refer to the reconstruction of the historical events behind the text, a study of the history of the text itself, the historical (or intended) sense of the text, or a historicist approach that excludes consideration of the supernatural in the interpretation of the past. John Barton has instead preferred the term "biblical criticism" for these reasons. In response, it has been argued that literary approaches may also have a historical character to them (such as the historical circumstances or motivations that led authors to making specific literary decisions), but more importantly, that the term "historical-critical method" need not refer to all critical approaches but only the ones with an interest in historical questions. Therefore, "biblical criticism" may be adopted as a broader term referring to all critical approaches to the Bible, whereas "historical criticism" only refers to those that relate back to the happenings of history.[25]

"Critical"

[edit]Others have been concerned in that the word "critical" might sound as though it implies a critique, or a hostile judgement of the text. However, in the context of the historical-critical method, the term "critical" is more appropriately understood as referring to an act of objective evaluation, and an approach that stresses not only the use of particular methods but in following them through to their conclusions, regardless of what those conclusions are.[26]

"Method"

[edit]The status of the historical-critical method as a "method" has been questioned. For the theologian Andrew Louth, it presupposes objective reality and an objective meaning embedded within a text that can be extracted by a skillful interpreter. John Barton argues that it is not so systematic as in the original sense of the "scientific method". Further, argues Barton, the scientific method is applied methodically and an understanding is only extracted from the results produced by the method, whereas the application of, say, source criticism, presupposes a prior understanding of the text. In response, Law has argued that the historical-critical method is similar as opposed to dissimilar to the scientific method in this regard, and that neither are theory-free. Instead, in using both, the investigator begins with a hypothesis, tests it by applying the method to what is being studied, and in light of the data produced, may either accept the initial hypothesis or revise it if needed.[27]

Question of commitment to a secular worldview

[edit]Another concern expressed by some is that the historical-critical method commits the investigator to a secular worldview, ruling out the possibility of any transcendental truth to the claims of the text being studied.[28] David Law has argued that this criticism is a strawman. Law argues that the method only eliminates a theological worldview as a presupposition, not as a conclusion. What the historical-critical method does, therefore, is allow one to study the text without prejudice as to what conclusion they will arrive at.[29] Similarly, the notion of the inspiration of a religious text is not rejected, but is treated with indifference insofar as it does not act as a guiding hand for the examination of the text.[30]

Criticisms since the 1970s

[edit]Since the 1970s, historical criticism has been said by some to be on the decline or even in "crisis" in the face of two trends. The first is the shift, by many scholars, away from studying historical questions related to past texts, and instead to literary questions that center around the reader. As part of this trend, postmodernist scholars have sought to challenge the concept of "meaning" itself as interpreted by historical critics who seek to study the historical, intended, or original meaning of a text. The second trend emerges from the work of feminist theologians who have argued that historical criticism is not impartial or objective, but instead is a tool for reasserting the hegemony of the interests of Western males. No reading of a text is free from ideological influences, including the readings produced by historians who apply historical criticism: just as with the texts they read, they too have social, political, and class interests. Proponents of historical criticism have responded to both of these charges. First, literary criticism has been emphasized as a supplement, as opposed to acting as a replacement, of historical criticism. Second, postcolonial and feminist readings of the Bible are easily integrated as a part of historical criticism, and these can play their role as a corrective of argumentation in the field that has proceeded from ideological influences. As such, historical criticism has been adopted by its critics, as in the case of feminist theologians who seek to recover the views of women in the Bible. Therefore, as opposed to being in crisis, historical criticism can be said to have been "expanded, corrected and complemented by the introduction of new methods."[31]

History

[edit]Precursors

[edit]A number of authors, throughout history, have applied methods that resembled the approaches used with the historical-critical method. For example, some Church Fathers engaged in disputes regarding some of the authorship attributions of some of the canonical biblical books, such as whether Paul was the author of Epistle to the Hebrews, or whether the author of the Gospel of John was also the author of the Book of Revelation, on the basis of stylistic criteria. Jerome reports widespread doubt concerning whether Peter was the true author of 2 Peter. Julius Africanus advanced several critical arguments in a letter to Origen as to why he believed that the story of Susanna in the Book of Daniel was not authentic. Augustine stressed the use of secular learning in interpreting the Bible against those who would instead follow the interpretation of the claimants of divine inspiration. Many have viewed the exegetical School of Antioch as strikingly critical, especially with respect to their confutation of various allegorical readings of the Bible as advanced in the School of Alexandria, viewed as being contrary to the original sense of the text. In 1440, Lorenzo Valla demonstrated that the Donation of Constantine was a forgery on the basis of linguistic, legal, historical, and political arguments. The Protestant Reformation saw an increase in efforts to plainly interpret the text of the Bible without the overriding lenses of tradition. The Middle Ages saw several trends that increasingly de-prioritized the allegorical readings, but it took until the Renaissance for them to lose their dominance. Approaches in this period saw an attitude that stressed going "back to the sources", collecting manuscripts (whose authenticity was assessed), establishing critical editions of religious texts, the learning of original languages, etc. The rise of vernacular translations of the Bible, alongside the rise of Protestantism, also challenged the exegetical monopoly of the Catholic Church. Joachim Camerarius argued that scriptures needed to be interpreted from the perspective of the authors, and Hugo Grotius argued that they needed to be interpreted in light of their ancient setting. John Lightfoot stressed the Jewish background of the New Testament, whose understanding would involve the study of texts included in the rabbinic literature. The rise of Deism and Rationalism added to the pressure exerted on traditional views of the Bible. For example, Johann August Ernesti sought to see the Bible not as a homogeneous whole but as a collection of distinct pieces of literature.[32][33]

Origins and use

[edit]Historical criticism as applied to the Bible began with Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677).[34] The phrase "higher criticism" became popular in Europe from the mid-18th century to the early 20th century to describe the work of such scholars as Jean Astruc (1684–1766), Johann Salomo Semler (1725–1791), Johann Gottfried Eichhorn (1752–1827), Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792–1860), and Wellhausen (1844–1918).[35] In academic circles, it now is the body of work properly considered "higher criticism", but the phrase is sometimes applied to earlier or later work using similar methods.

"Higher criticism" originally referred to the work of German biblical scholars of the Tübingen School. After the groundbreaking work on the New Testament by Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), the next generation, which included scholars such as David Friedrich Strauss (1808–1874) and Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–1872), analyzed in the mid-19th century the historical records of the Middle East from biblical times, in search of independent confirmation of events in the Bible. The latter scholars built on the tradition of Enlightenment and Rationalist thinkers such as John Locke (1632–1704), David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Gotthold Lessing, Gottlieb Fichte, G. W. F. Hegel (1770–1831) and the French rationalists.

Such ideas influenced thought in England through the work of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and, in particular, through George Eliot's translations of Strauss's The Life of Jesus (1846) and Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity (1854). In 1860, seven liberal Anglican theologians began the process of incorporating this historical criticism into Christian doctrine in Essays and Reviews, causing a five-year storm of controversy, which completely overshadowed the arguments over Charles Darwin's newly published On the Origin of Species. Two of the authors were indicted for heresy and lost their jobs by 1862, but in 1864, they had the judgement overturned on appeal. La Vie de Jésus (1863), the seminal work by a Frenchman, Ernest Renan (1823–1892), continued in the same tradition as Strauss and Feuerbach. In Catholicism, L'Evangile et l'Eglise (1902), the magnum opus by Alfred Loisy against the Essence of Christianity of Adolf von Harnack[citation needed] (1851–1930) and La Vie de Jesus of Renan, gave birth to the modernist crisis (1902–61). Some scholars, such as Rudolf Bultmann (1884–1976) have used higher criticism of the Bible to "demythologize" it.

Reception in religious circles

[edit]Catholic Church

[edit]The Catholic Church did not adopt historical criticism as an approach until the twentieth century. The method was rejected by the Council of Trent in 1546, stressing the interpretation promoted by the Church as opposed to personal interpretation. The earlier decision was confirmed at the First Vatican Council in 1869–1870. In 1907, Pope Pius X condemned historical criticism in the 1907 Lamentibili sane exitu.[36] However, around the time of the mid-twentieth century, attitudes changed. In 1943, Pope Pius XII issued the encyclical Divino afflante Spiritu, making historical criticism not only permissible but "a duty".[36] Catholic biblical scholar Raymond E. Brown described this encyclical as a "Magna Carta for biblical progress".[37] In 1964, the Pontifical Biblical Commission published the Instruction on the Historical Truth of the Gospels, which confirmed the method and delineated how its tools can be used to aid in exegesis.[38] The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) reconfirmed this approach. Another reiteration of this came with The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church by the Pontifical Biblical Institute. Due to these trends, Roman Catholic scholars entered into academia and have since made substantial contributions to the field of biblical studies.[39]

Lutheran Church

[edit]In 1966, the Commission on Theology and Church Relations of the Luthern Church-Missouri Synod approved the steps taken towards acceptance of historical criticism as had been done earlier by the Catholic Church.[38]

Evangelical objections

[edit]Beginning in the nineteenth century, effort on the part of evangelical scholars and writers was expended in opposing theories of historical critical scholars. Evangelicals at the time accused the 'higher critics' of representing their dogmas as indisputable facts.[citation needed] Bygone churchmen such as James Orr, William Henry Green, William M. Ramsay, Edward Garbett, Alfred Blomfield, Edward Hartley Dewart, William B. Boyce, John Langtry, Dyson Hague, D. K. Paton, John William McGarvey, David MacDill, J. C. Ryle, Charles Spurgeon and Robert D. Wilson pushed back against the judgements of historical critics. Some of these counter-views still have support in the more conservative evangelical circles today. There has never been a centralised stance on historical criticism, and Protestant denominations divided over the issue (e.g. Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy, Downgrade controversy etc.). The historical-grammatical method of biblical interpretation has been preferred by evangelicals, but is not held by the preponderance of contemporary scholars affiliated to major universities.[40] Gleason Archer Jr., O. T. Allis, C. S. Lewis,[41] Gerhard Maier, Martyn Lloyd-Jones, Robert L. Thomas, F. David Farnell, William J. Abraham, J. I. Packer, G. K. Beale and Scott W. Hahn rejected the historical-critical hermeneutical method as evangelicals.

Evangelical Christians have often partly attributed the decline of the Christian faith (i.e. declining church attendance, fewer conversions to faith in Christ and biblical devotion, denudation of the Bible's supernaturalism, syncretism of philosophy and Christian revelation etc.) in the developed world to the consequences of historical criticism. Acceptance of historical critical dogmas engendered conflicting representations of Protestant Christianity.[42] The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy in Article XVI affirms traditional inerrancy, but not as a response to 'negative higher criticism.'[43]

On the other hand, attempts to revive the extreme historical criticism of the Dutch Radical School by Robert M. Price, Darrell J. Doughty and Hermann Detering have also been met with strong criticism and indifference by mainstream scholars. Such positions are nowadays confined to the minor Journal of Higher Criticism and other fringe publications.[44]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Hahn, Scott, ed. (2009). Catholic Bible dictionary (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51229-9.

- ^ Soulen, Richard N. (2001). Handbook of Biblical Criticism. John Knox. pp. 108, 190.

- ^ a b Soulen, Richard N.; Soulen, R. Kendall (2001). Handbook of biblical criticism (3rd ed., rev. and expanded. ed.). Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-664-22314-1.

- ^ a b c Sinai, Nicolai (2017). The Qur'an: a historical-critical introduction. The new Edinburgh Islamic surveys. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 2–5. ISBN 978-0-7486-9576-8.

- ^ Oliver, Isaac (2023). "The Historical-Critical Study of Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Scriptures". In Dye, Guillame (ed.). Early Islam: The Sectarian Milieu of Late Antiquity?. Editions de l'Universite de Bruxelles.

- ^ Krentz 1975, p. 35–47.

- ^ Krentz 1975, p. 48.

- ^ Krentz 1975, p. 53–54.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 25–26.

- ^ Law 2012, p. viii–ix.

- ^ a b Soulen, Richard N. (2001). Handbook of Biblical Criticism. John Knox. p. 79.

- ^ Krentz 1975, p. 56–57.

- ^ Krentz 1975, p. 66–67.

- ^ Krentz 1975, p. 57–61.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 20.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 22–23.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 23–24.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 81–82.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 113–123.

- ^ Pregill 2023, p. 549–560.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 140–143.

- ^ "Religious Studies Department, Santa Clara University". Archived from the original on February 28, 2006.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 181–182.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 194–196.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 4–8.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 8.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 10–14.

- ^ Meier 1977.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 9–10.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 75–80.

- ^ Krentz 1975, p. 6–10.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 25–52.

- ^

Compare:

Durant, Will (1961) [1926]. "4: Spinoza". The Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the Great Philosophers of the Western World. A Touchstone book. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 125. ISBN 9780671201593. Retrieved 2017-07-23.

...the movement of higher criticism which Spinoza initiated has made into platitudes the propositions for which Spinoza risked his life.

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2007

- ^ a b Law 2012, p. 74.

- ^ Brown, Raymond E. (1990). "Church Pronouncements". In Brown, Raymond E.; Fitzmyer, Joseph A.; Murphy, Roland E. (eds.). The New Jerome Biblical Commentary. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 1167. Cited in Donahue 1993, p. 76.

- ^ a b Krentz 1975, p. 2.

- ^ Law 2012, p. 75.

- ^ https://ehrmanblog.org/how-do-we-know-what-most-scholars-think/ Archived 2021-07-30 at the Wayback Machine Quote: "First, what is taught about the New Testament to undergraduates at the colleges and universities that are NOT evangelical? You can pick any type of school you want, and I (and virtually every other scholar in the field) can tell you the answer, simply because I (and they) know (either personally or through reputation) virtually every senior (and many junior) scholar at those places. These scholars pretty much all toe the line that I indicate: about John, 1 Timothy, the dating of the Gospels, and most other critical issues."

- ^ Lewis, Clive Staples (1969). "Modern Theology and Biblical Criticism". BYU Studies Quarterly. 9 (1).

- ^ "D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones on the Authority of Scripture—We Must Choose Between Two Positions". Albert Mohler. 19 June 2005. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ Baptist Church, Duncan Street. "Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy". duncanstreetbaptistchurch.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2023-01-22. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2012-03-20). Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-208994-6. Archived from the original on 2022-08-08. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

Sources

[edit]- Fogarty, Gerald P., S.J. American Catholic Biblical Scholarship: A History from the Early Republic to Vatican II, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1989, ISBN 0-06-062666-6. Nihil obstat by Raymond E. Brown, S.S., and Joseph A. Fitzmyer, S.J.

- Krentz, Edgar (1975). The Historical-Critical Method (PDF). Fortress Press.

- Law, David R. (2012). The Historical-Critical Method: A Guide for the Perplexed. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-40012-3.

- Meier, Gerhard (1977). The End of the Historical–Critical Method. Concordia Publishing House.

- Pregill, Michael (2023). "From the Mishnah to Muḥammad: Jewish Traditions of Late Antiquity and the Composition of the Qur'an". Studies in Late Antiquity. 7 (4): 516–560. doi:10.1525/sla.2023.7.4.516.

- Wilson, Robert Dick. Is the Higher Criticism Scholarly? Clearly Attested Facts Showing That the Destructive "Assured Results of Modern Scholarship" Are Indefensible. Philadelphia: The Sunday School Times, 1922. 62 pp.; reprinted in Christian News 29, no. 9 (4 March 1991): 11–14.

Further reading

[edit]- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (2008). The Interpretation of Scripture: In Defense of the Historical-Critical Method. Paulist Press.

External links

[edit]- Rutgers University: Synoptic Gospels Primer: introduction to the history of literary analysis of the Greek gospels, and aids in confronting the range of factors that need to be taken into consideration in accounting for the literary relationship of the first three gospels.

- Journal of Higher Criticism

- From the Divine Oracle to Higher Criticism

- Catholic Encyclopedia article "Biblical Criticism (Higher)"

- Dictionary of the history of Ideas – Modernism and the Church

- Dictionary of the history of Ideas: Modernism in the Christian Church

- Teaching Bible based on Higher Criticism

- "Historical Criticism and the Evangelical" by Grant Osborne

- "From the Divine Oracle to Higher Criticism" from The Warfare of Science With Theology by Andrew White, 1896

- Catholic Encyclopedia article (1908) "Biblical Criticism (Higher)"

- Radical criticism, link to articles in English

- Library of latest modern books of biblical studies and biblical criticism