Alcoholic liver disease

| Alcoholic liver disease | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

Alcoholic liver disease is a term that encompasses the hepatic manifestations of alcohol over consumption, including fatty liver, alcoholic hepatitis, and chronic hepatitis with hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis.[1] It is the major cause of liver disease in Western countries. Although steatosis (fatty liver) will develop in any individual who consumes a large quantity of alcoholic beverages over a long period of time, this process is transient and reversible.[1] Of all chronic heavy drinkers, only 15–20% develop hepatitis or cirrhosis, which can occur concomitantly or in succession.[2]

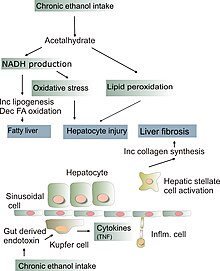

How alcohol damages the liver is not completely understood. 80% of alcohol passes through the liver to be detoxified. Chronic consumption of alcohol results in the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alpha, IL6 and IL8), oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and acetaldehyde toxicity. These factors cause inflammation, apoptosis and eventually fibrosis of liver cells. Why this occurs in only a few individuals is still unclear. Additionally, the liver has tremendous capacity to regenerate and even when 75% of hepatocytes are dead, it continues to function as normal.[3]

Risk factors

The risk factors presently known are:

- Quantity of alcohol taken: consumption of 60–80g per day (about 75–100 ml/day) for 20 years or more in men, or 20g/day (about 25 ml/day) for women significantly increases the risk of hepatitis and fibrosis by 7 to 47%,[1][4]

- Pattern of drinking: drinking outside of meal times increases up to 2.7 times the risk of alcoholic liver disease.[2]

- Gender: females are twice as susceptible to alcohol related liver disease, and may develop alcoholic liver disease with shorter durations and doses of chronic consumption. The lesser amount of alcohol dehydrogenase secreted in the gut, higher proportion of body fat in women, and changes in fat absorption due to the with menstrual cycle may explain this phenomenon.[2]

- Hepatitis C infection: a concomitant hepatitis C infection significantly accelerates the process of liver injury.[2]

- Genetic factors: genetic factors predispose both to alcoholism and to alcoholic liver disease. Monozygotic twins are more likely to be alcoholics and to develop liver cirrhosis than dizygotic twins. Polymorphisms in the enzymes involved in the metabolism of alcohol, such as ADH, ALDH, CYP4502E1, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cytokine polymorphism may partly explain this genetic component. However, no specific polymorphisms have currently been firmly linked to alcoholic liver disease.

- Iron overload (hemochromatosis)

- Diet: malnutrition, particularly vitamin A and E deficiencies, can worsen alcohol-induced liver damage by preventing regeneration of hepatocytes. This is particularly a concern as alcoholics are usually malnourished because of a poor diet, anorexia, and encephalopathy.[2]

Pathophysiology

Fatty change

Fatty change, or steatosis is the accumulation of fatty acids in liver cells. These can be seen as fatty globules under the microscope. Alcoholism causes development of large fatty globules (macro vesicular steatosis) throughout the liver and can begin to occur after a few days of heavy drinking.[5] Alcohol is metabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) into acetaldehyde, then further metabolized by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) into acetic acid, which is finally oxidized into carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O).[6] This process generates NADH, and increases the NADH/NAD+ ratio. A higher NADH concentration induces fatty acid synthesis while a decreased NAD level results in decreased fatty acid oxidation. Subsequently, the higher levels of fatty acids signal the liver cells to compound it to glycerol to form triglycerides. These triglycerides accumulate, resulting in fatty liver.

Alcoholic hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitis is characterized by the inflammation of hepatocytes. Between 10% and 35% of heavy drinkers develop alcoholic hepatitis (NIAAA, 1993). While development of hepatitis is not directly related to the dose of alcohol, some people seem more prone to this reaction than others (citation?). This is called alcoholic steato necrosis and the inflammation appears to predispose to liver fibrosis. Inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alpha, IL6 and IL8) are thought to be essential in the initiation and perpetuation of liver injury by inducing apoptosis and necrosis. One possible mechanism for the increased activity of TNF-α is the increased intestinal permeability due to liver disease. This facilitates the absorption of the gut-produced endotoxin into the portal circulation. The Kupffer cells of the liver then phagocytose endotoxin, stimulating the release of TNF-α. TNF-α then triggers apoptotic pathways through the activation of caspases, resulting in cell death.[2]

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is a late stage of serious liver disease marked by inflammation (swelling), fibrosis (cellular hardening) and damaged membranes preventing detoxification of chemicals in the body, ending in scarring and necrosis (cell death). Between 10% to 20% of heavy drinkers will develop cirrhosis of the liver (NIAAA, 1993). Acetaldehyde may be responsible for alcohol-induced fibrosis by stimulating collagen deposition by hepatic stellate cells.[2] The production of oxidants derived from NADPH oxi- dase and/or cytochrome P-450 2E1 and the formation of acetaldehyde-protein adducts damage the cell membrane.[2]

Symptoms include jaundice (yellowing), liver enlargement, and pain and tenderness from the structural changes in damaged liver architecture. Without total abstinence from alcohol use, will eventually lead to liver failure. Late complications of cirrhosis or liver failure include portal hypertension (high blood pressure in the portal vein due to the increased flow resistance through the damaged liver), coagulation disorders (due to impaired production of coagulation factors), ascites (heavy abdominal swelling due to build up of fluids in the tissues) and other complications, including hepatic encephalopathy and the hepatorenal syndrome.

Cirrhosis can also result from other causes than alcohol abuse, such as viral hepatitis and heavy exposure to toxins other than alcohol. The late stages of cirrhosis may look similar medically, regardless of cause. This phenomenon is termed the "final common pathway" for the disease.

Fatty change and alcoholic hepatitis with abstinence can be reversible. The later stages of fibrosis and cirrhosis tend to be irreversible, but can usually be contained with abstinence for long periods of time.

Diagnosis

There are many tests to assess alcoholic liver damage. Besides blood examination, doctors use ultrasound and a CT scan to assess liver damage. In some cases a liver biopsy is performed. This minor procedure is done under local anesthesia, and involves placing a small needle in the liver and obtaining a piece of tissue. The tissue is then sent to the laboratory to be examined under a microscope. The differential diagnoses for fatty liver non-alcoholic steatosis, drug-induced steatosis, include diabetes, obesity and starvation.

Treatment

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2010) |

The first treatment of alcohol-induced liver disease is cessation of alcohol consumption. This is the only way to reverse liver damage or prevent liver injury from worsening. Without treatment, most patients with alcohol-induced liver damage will develop liver cirrhosis. Other treatment for alcoholic hepatitis include:

Early Treatments

In the 1920s, it was believed that a "Liver Exercise" could help with a large amount of Alcohol Consumption.[citation needed]

Nutrition

Doctors recommend a calorie-rich diet to help the liver in its regeneration process. Dietary fat must be reduced because fat interferes with alcohol metabolism. The diet is usually supplemented with vitamins and dietary minerals (including calcium and iron). [citation needed]

Many nutritionists recommend a diet high in protein, with frequent small meals eaten during the day, about 5–6 instead of the usual 3. Nutritionally, supporting the liver and supplementing with nutrients that enhance liver function is recommended. These include carnitine, which will help reverse fatty livers, and vitamin C, which is an antioxidant, aids in collagen synthesis, and increases the production of neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine and serotonin, as well as supplementing with the nutrients that have been depleted due to the alcohol consumption. Eliminating any food that may be manifesting as an intolerance and alkalizing the body is also important. There are some supplements that are recommended to help reduce cravings for alcohol, including choline, glutamine, and vitamin C. As research shows glucose increases the toxicity of centrilobular hepatotoxicants by inhibiting cell division and repair, it is suggested fatty acids are used by the liver instead of glucose as a fuel source to aid in repair; thus, it is recommended the patient consumes a diet high in protein and essential fatty acids, e.g. omega 3. Cessation of alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking, and increasing exercise are lifestyle recommendations to decrease the risk of liver disease caused by alcoholic stress. [citation needed]

Drugs

Abstinence from alcohol intake and nutritional modification form the backbone in the management of ALD. Symptom treatment can include: corticosteroids for severe cases, anticytokines (infliximab and pentoxifylline), propylthiouracil to modify metabolism and colchicine to inhibit hepatic fibrosis.

Antioxidants

It is widely believed[by whom?] that alcohol-induced liver damage occurs via generation of oxidants.[citation needed] Thus alternative health care practitioners routinely recommend natural antioxidant supplements like milk thistle[citation needed]. Currently, there exists no substantive clinical evidence to suggest that milk thistle or other antioxidant supplements are efficacious beyond placebo in treating liver disease caused by chronic alcohol consumption.[7][8]

Transplant

When all else fails and the liver is severely damaged, the only alternative is a liver transplant. While this is a viable option, liver transplant donors are scarce and usually there is a long waiting list in any given hospital. One of the criteria to become eligible for a liver transplant is to discontinue alcohol consumption for a minimum of six months.[9]

Complications and prognosis

As the liver scars, the blood vessels become noncompliant and narrow. This leads to increased pressure in blood vessels entering the liver. Over time, this causes a backlog of blood (portal hypertension), and is associated with massive bleeding. Enlarged veins, also known as varicose veins, also develop to bypass the blockages in the liver. These veins are very fragile and have a tendency to rupture and bleed. Variceal bleeding can be life-threatening and needs emergency treatment. Once the liver is damaged, fluid builds up in the abdomen and legs. The fluid buildup presses on the diaphragm and can make breathing very difficult.[10] As liver damage progresses, the liver is unable to get rid of pigments like bilirubin and both the skin and eyes turn yellow (jaundice). The dark pigment also causes the urine to appear dark; however, the stools appear pale. Also with the progression of the disease, the liver can release toxic substances (including ammonia) which then lead to brain damage. This results in altered mental state, and may cause behavior and personality changes.

References

- ^ a b c O'Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ (2010). "Alcoholic liver disease" (PDF). Hepatology. 51 (1): 307–28. doi:10.1002/hep.23258. PMID 20034030.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Menon KV, Gores GJ, Shah VH (2001). "Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of alcoholic liver disease" (PDF). Mayo Clin. Proc. 76 (10): 1021–9. PMID 11605686.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Longstreth, George F.; Zieve, David (eds.) (18 October 2009). "Alcoholic Liver Disease". MedLinePlus: Trusted Health Information for You. Bethesda, MD: US National Library of Medicine & National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mandayam S, Jamal MM, Morgan TR (2004). "Epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease". Semin. Liver Dis. 24 (3): 217–32. doi:10.1055/s-2004-832936. PMID 15349801.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Inaba, Darryl; Cohen, William B. (2004). Uppers, downers, all arounders: physical and mental effects of psychoactive drugs (5th ed.). Ashland, Or: CNS Publications. ISBN 0-926544-27-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Inaba & Cohen 2004, p. 185

- ^

Rambaldi A, Jacobs BP, Iaquinto G, Gluud C (2005). "Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C liver diseases—a systematic cochrane hepato-biliary group review with meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100 (11): 2583–91. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00262.x. PMID 16279916.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Bjelakovic G, Gluud LL, Nikolova D, Bjelakovic M, Nagorni A, Gluud C (2011). "Antioxidant supplements for liver diseases". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD007749. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007749.pub2. PMID 21412909.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Alcoholic Liver Disease: Introduction". Johns Hopkins Medicine: Gastroenterology & Hepatology. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Hospital. 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ^ "Alcoholic Liver Disease" (PDF). Common Gastrointestinal Problems: A Consumer Health Guide. Arlington, VA: American College of Gastroenterology. 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2010. (Plain text version also available.)

External links

- Morphology of Alcoholic Liver Disease | Medchrome

- "Alcoholic liver disease (per capita) (most recent) by country". NationMaster. Retrieved 29 July 2009.