Hallstatt culture

| |

| Geographical range | Europe |

|---|---|

| Period | Late Bronze Age, Early Iron Age |

| Dates | 1200 – 500 BC Hallstatt A (1200 – 1050 BC); Hallstatt B (1050 – 800 BC); Hallstatt C (800 – 500 BC); Hallstatt D (620 – 450 BC) |

| Type site | Hallstatt |

| Preceded by | Urnfield culture |

| Followed by | La Tène culture |

The Hallstatt culture was the predominant Western and Central European culture of Late Bronze Age (Hallstatt A, Hallstatt B) from the 12th to 8th centuries BC and Early Iron Age Europe (Hallstatt C, Hallstatt D) from the 8th to 6th centuries BC, developing out of the Urnfield culture of the 12th century BC (Late Bronze Age) and followed in much of its area by the La Tène culture. It is commonly associated with Proto-Celtic populations. Older assumptions of the early 20th century of Illyrians having been the bearers of especially the Eastern Hallstatt culture are indefensible and archeologically unsubstantiated.[2][3]

It is named for its type site, Hallstatt, a lakeside village in the Austrian Salzkammergut southeast of Salzburg, where there was a rich salt mine, and some 1,300 burials are known, many with fine artifacts. Material from Hallstatt has been classified into four periods, designated "Hallstatt A" to "D". Hallstatt A and B are regarded as Late Bronze Age and the terms used for wider areas, such as "Hallstatt culture", or "period", "style" and so on, relate to the Iron Age Hallstatt C and D.

By the 6th century BC, it had expanded to include wide territories, falling into two zones, east and west, between them covering much of western and central Europe down to the Alps, and extending into northern Italy. Parts of Britain and Iberia are included in the ultimate expansion of the culture.

The culture was based on farming, but metal-working was considerably advanced, and by the end of the period long-range trade within the area and with Mediterranean cultures was economically significant. Social distinctions became increasingly important, with emerging elite classes of chieftains and warriors, and perhaps those with other skills. Society was organized on a tribal basis, though very little is known about this. Only a few of the largest settlements, like Heuneburg in the south of Germany, were towns rather than villages by modern standards.

Chronology

| Bronze Age Central Europe[4] | |

|---|---|

| Bell Beaker | 2600–2200 BC |

| Bz A | 2200–1600 BC |

| Bz B | 1600–1500 BC |

| Bz C | 1500–1300 BC |

| Bz D | 1300–1200 BC |

| Ha A | 1200–1050 BC |

| Ha B | 1050–800 BC |

| Iron Age Central Europe | |

| Hallstatt | |

| Ha C | 800–620 BC |

| Ha D | 620–450 BC |

| La Tène | |

| LT A | 450–380 BC |

| LT B | 380–250 BC |

| LT C | 250–150 BC |

| LT D | 150–1 BC |

| Roman period[5] | |

| B | AD 1–150 |

| C | AD 150–375 |

According to Paul Reinecke's time-scheme from 1902,[6] the end of the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age were divided into four periods:

Bronze Age Urnfield culture:

- HaA (1200-1050 BC)

- HaB (1050-800 BC)

Early Iron Age Hallstatt culture:

- HaC (800-620 BC)

- HaD (620-450 BC)[7]

Paul Reinecke based his chronological divisions on finds from the south of Germany.

Already by 1881 Otto Tischler had made analogies to the Iron Age in the Northern Alps based on finds of brooches from graves in the south of Germany.[8]

Absolute dating

It has proven difficult to use radiocarbon dating for the Early Iron Age due to the so-called "Hallstatt-Plateau", a phenomenon where radiocarbon dates cannot be distinguished between 750 to 400 BC. There are workarounds however, such as the wiggle matching technique. Therefore dating in this time-period has been based mainly on Dendrochronology and relative dating.

For the beginning of HaC wood pieces from the Cart Grave of Wehringen (Landkreis Augsburg) deliver a solid dating in 778 ± 5 BC (Grave Barrow 8).[9]

Despite missing an older Dendro-date for HaC, the convention remains that the Hallstatt Period begins together with the arrival of the iron ore processing technology around 800 BC.

Relative dating

HaC is dated according to the presence of Mindelheim-type swords, binocular brooches, harp brooches, and arched brooches.

Based on the quickly changing fashions of brooches, it was possible to divide HaD into three stages (D1-D3). In HaD1 snake brooches are predominant, while in HaD2 drum brooches appear more often, and in HaD3 the double-drum and embellished foot brooches.

The transition to the La Tène Period is often connected with the emergence of the first animal-shaped brooches, with Certosa-type and with Marzabotto-type brooches.

Hallstatt type site

In 1846, Johann Georg Ramsauer (1795–1874) discovered a large prehistoric cemetery near Hallstatt, Austria (47°33′40″N 13°38′31″E / 47.561°N 13.642°E), which he excavated during the second half of the 19th century. Eventually the excavation would yield 1,045 burials, although no settlement has yet been found. This may be covered by the later village, which has long occupied the whole narrow strip between the steep hillsides and the lake. Some 1,300 burials have been found, including around 2,000 individuals, with women and children but few infants.[10] Nor is there a "princely" burial, as often found near large settlements. Instead, there are a large number of burials varying considerably in the number and richness of the grave goods, but with a high proportion containing goods suggesting a life well above subsistence level.

The community at Hallstatt was untypical of the wider, mainly agricultural, culture, as its booming economy exploited the salt mines in the area. These had been worked from time to time since the Neolithic period, and in this period were extensively mined with a peak from the 8th to 5th centuries BC. The style and decoration of the grave goods found in the cemetery are very distinctive, and artifacts made in this style are widespread in Europe. In the mine workings themselves, the salt has preserved many organic materials such as textiles, wood and leather, and many abandoned artifacts such as shoes, pieces of cloth, and tools including miner's backpacks, have survived in good condition.[11]

Finds at Hallstatt extend from about 1200 BC until around 500 BC, and are divided by archaeologists into four phases:

Hallstatt A–B (1200–800 BC) are part of the Bronze Age Urnfield culture. In this period, people were cremated and buried in simple graves. In phase B, tumulus (barrow or kurgan) burial becomes common, and cremation predominates. The "Hallstatt period" proper is restricted to HaC and HaD (800–450 BC), corresponding to the early European Iron Age. Hallstatt lies in the area where the western and eastern zones of the Hallstatt culture meet, which is reflected in the finds from there.[12] Hallstatt D is succeeded by the La Tène culture.

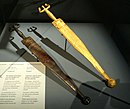

Hallstatt C is characterized by the first appearance of iron swords mixed amongst the bronze ones. Inhumation and cremation co-occur. For the final phase, Hallstatt D, daggers, almost to the exclusion of swords, are found in western zone graves ranging from c. 600–500 BC.[13] There are also differences in the pottery and brooches. Burials were mostly inhumations. Halstatt D has been further divided into the sub-phases D1–D3, relating only to the western zone, and mainly based on the form of brooches.[13]

Major activity at the site appears to have finished about 500 BC, for reasons that are unclear. Many Hallstatt graves were robbed, probably at this time. There was widespread disruption throughout the western Hallstatt zone, and the salt workings had by then become very deep.[14] By then the focus of salt mining had shifted to the nearby Hallein Salt Mine, with graves at Dürrnberg nearby where there are significant finds from the late Hallstatt and early La Tène periods, until the mid-4th century BC, when a major landslide destroyed the mineshafts and ended mining activity.[15]

Much of the material from early excavations was dispersed,[10] and is now found in many collections, especially German and Austrian museums, but the Hallstatt Museum in the town has the largest collection.

- Finds from the Hallstatt site

-

Bronze vessel with cow and calf, Hallstatt

-

Wood and leather carrying pack from the mine

-

Bronze artefacts from Hallstatt

-

Textile fragment from the salt mine

-

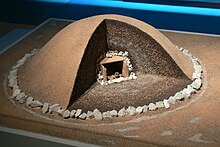

Hallstatt grave reconstruction

-

Ha C axehead, Hallstatt

-

Preserved wood stairs from the Hallstatt salt mine

-

Fibula brooch with animal figures

-

Tools and weapons from the Hallstatt cemetery

-

"Antenna hilt" Hallstatt 'D' swords, from Hallstatt

-

Finds from the Hallstatt cemetery

-

Finds from the Hallstatt cemetery

-

Gold and bronze beltplates from Hallstatt

Culture and trade

Languages

It is probable that some if not all of the diffusion of Hallstatt culture took place in a Celtic-speaking context.[17][18][19][20] In northern Italy the Golasecca culture developed with continuity from the Canegrate culture.[21][22] Canegrate represented a completely new cultural dynamic to the area expressed in pottery and bronzework, making it a typical western example of the western Hallstatt culture.[21][22][23]

The Lepontic Celtic language inscriptions of the area show the language of the Golasecca culture was clearly Celtic making it probable that the 13th-century BC precursor language of at least the western Hallstatt was also Celtic or a precursor to it.[21][22] Lepontic inscriptions have also been found in Umbria,[24] in the area which saw the emergence of the Terni culture, which had strong similarities with the Celtic cultures of Hallstatt and La Tène.[25] The Umbrian necropolis of Terni, which dates back to the 10th century BC, was virtually identical in every aspect to the Celtic necropolis of the Golasecca culture.[26]

Trade

Trade with Greece is attested by finds of Attic black-figure pottery in the elite graves of the late Hallstatt period. It was probably imported via Massilia (Marseilles).[27] Other imported luxuries include amber, ivory (as found at the Grafenbühl Grand Tomb) and probably wine. Red kermes dye was imported from the south as well; it was found at Hochdorf. Notable individual imports include the Vix krater (the largest known metal vessel from Western classical antiquity), the Etruscan lebes from Sainte-Colombe-sur-Seine, and the Grächwil Hydria.

Settlements

The largest settlements were mostly fortified, situated on hilltops, and frequently included the workshops of bronze-, silver-, and goldsmiths. Major settlements are known as 'princely seats' (or Fürstensitze in German), and are characterized by elite residences, rich burials, monumental buildings and fortifications. These central sites are described as urban or proto-urban by numerous scholars,[28][29][30] and as 'the first cities north of the Alps' by some authors.[31][32] Typical sites of this type are the Heuneburg on the upper Danube surrounded by nine very large grave tumuli, Mont Lassois in eastern France near Châtillon-sur-Seine with, at its foot, the very rich grave at Vix,[33] and the hill fort at Molpír in Slovakia. However, most settlements were much smaller villages. The large monumental site of Alte Burg may have had a religious or ceremonial function, and possibly served as a location for games and competitions.[34][35]

At the end of the Hallstatt period many major centres were abandoned and there was a return to a more decentralized settlement pattern, prior to the emergence of urban centres across temperate Europe in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC during the La Tène period.[36]

Burial rites

In the central Hallstatt regions toward the end of the period (Ha D), very rich graves of high-status individuals under large tumuli are found near the remains of fortified hilltop settlements. Tumuli graves had a chamber, rather large in some cases, lined with timber and with the body and grave goods set about the room. There are some chariot or wagon burials, including (possibly) Býčí Skála,[37] Vix and Hochdorf.[38] A model of a chariot made from lead has been found in Frögg, Carinthia, and clay models of horses with riders are also found. Wooden "funerary carts", presumably used as hearses and then buried, are sometimes found in the grandest graves. Pottery and bronze vessels, weapons, elaborate jewellery made of bronze and gold, as well as a few stone stelae (especially the famous Warrior of Hirschlanden) are found at such burials.[39] The daggers that largely replaced swords in chief's graves in the west were probably not serious weapons, but badges of rank, and used at the table.[13]

Social structure

The material culture of Western Hallstatt culture was apparently sufficient to provide a stable social and economic equilibrium. The founding of Marseille and the penetration by Greek and Etruscan culture after c. 600 BC, resulted in long-range trade relationships up the Rhone valley which triggered social and cultural transformations in the Hallstatt settlements north of the Alps. Powerful local chiefdoms emerged which controlled the redistribution of luxury goods from the Mediterranean world that is also characteristic of the La Tène culture.

The apparently largely peaceful and prosperous life of Hallstatt D culture was disrupted, perhaps even collapsed, right at the end of the period. There has been much speculation as to the causes of this, which remain uncertain. Large settlements such as Heuneburg and the Burgstallkogel were destroyed or abandoned, rich tumulus burials ended, and old ones were looted. There was probably a significant movement of population westwards, and the succeeding La Tène culture developed new centres to the west and north, their growth perhaps overlapping with the final years of the Hallstatt culture.[14]

Technology

Occasional iron artefacts had been appearing in central and western Europe for some centuries before 800 BC (an iron knife or sickle from Ganovce in Slovakia, dating to the 18th century BC, is possibly the earliest evidence of smelted iron in Central Europe).[40] By the later Urnfield (Hallstatt B) phase, some swords were already being made and embellished in iron in eastern Central Europe, and occasionally much further west.[41][40] Initially iron was rather exotic and expensive, and sometimes used as a prestige material for jewellery.[42] Iron swords became more common after c. 800 BC,[43] and steel was also produced from c. 800 BC as part of the production of swords.[44] The production of high-carbon steel is attested in Britain after c. 490 BC.[45]

The remarkable uniformity of spoked-wheel wagons from across the Hallstatt region indicates a certain standardisation of production methods, which included the use of lathe-turning.[46] Iron tyres were also developed and refined in this period, leading to the invention of shrunk-on iron tyres without nails in the later La Tène period.[46] The potter's wheel appeared towards the end of the Hallstatt period.[47]

The extensive use of planking and massive squared beams indicates the use of long saw blades and possibly two-man sawing.[48] The planks of the Hohmichele burial chamber (6th c. BC), which were over 6m long and 35cm wide, appear to have been sawn by a large-timber-yard saw.[49] The construction of monumental buildings such as the Vix palace further demonstrates a "mastery of geometry and carpentry" that was capable of freeing up vast interior spaces.[50]

-

Funerary wagon, Strasbourg Museum

-

Wagon wheel, Vix Grave, France

-

Wagon wheel hub from the Vix Grave

-

Pottery from Heuneburg, Germany

-

Gold bracelets from Sainte-Colombe-sur-Seine

-

The Vix krater, imported from Greece

-

Hallstatt 'C' swords in Wels Museum, Austria.

-

Dagger with "antenna hilt"

-

Ceramics and sword with gold hilt from Gomadingen

-

Metal vessels from Kleinklein

-

Gold artefacts from the Heuneburg

-

Burial goods from Oss, Netherlands

-

Cult wagon from La Côte-Saint-André, France.[51]

Art

At least the later periods of Hallstatt art from the western zone are generally agreed to form the early period of Celtic art.[52] Decoration is mostly geometric and linear, and best seen on fine metalwork finds from graves (see above). Styles differ, especially between the west and east, with more human figures and some narrative elements in the latter. Animals, with waterfowl a particular favourite, are often included as part of other objects, more often than humans, and in the west there is almost no narrative content such as scenes of combat depicted. These characteristics were continued into the succeeding La Tène style.[53]

Imported luxury art is sometimes found in rich elite graves in the later phases, and certainly had some influence on local styles. The most spectacular objects, such as the Strettweg Cult Wagon,[54] the Warrior of Hirschlanden and the bronze couch supported by "unicyclists" from the Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave are one of a kind in finds from the Hallstatt period, though they can be related to objects from other periods.[55]

More common objects include weapons, in Ha D often with hilts terminating in curving forks ("antenna hilts").[13] Jewellery in metal includes fibulae, often with a row of disks hanging down on chains, armlets and some torcs. This is mostly in bronze, but "princely" burials include items in gold.

The origin of the narrative scenes of the eastern zone, from Hallstatt C onwards, is generally traced to influence from the Situla art of northern Italy and the northern Adriatic, where these bronze buckets began to be decorated in bands with figures in provincial Etruscan centres influenced by Etruscan and Greek art. The fashion for decorated situlae spread north across neighbouring cultures including the eastern Hallstatt zone, beginning around 600 BC and surviving until about 400 BC; the Vače situla is a Slovenian example from near the final period. The style is also found on bronze belt plates, and some of the vocabulary of motifs spread to influence the emerging La Tène style.[56]

According to Ruth and Vincent Megaw, "Situla art depicts life as seen from a masculine viewpoint, in which women are servants or sex objects; most of the scenes which include humans are of the feasts in which the situlae themselves figure, of the hunt or of war".[57] Similar scenes are found on other vessel shapes, as well as bronze belt-plaques.[58] The processions of animals, typical of earlier examples, or humans derive from the Near East and Mediterranean, and Nancy Sandars finds the style shows "a gaucherie that betrays the artist working in a way that is uncongenial, too much at variance with the temper of the craftsmen and the craft". Compared to earlier styles that arose organically in Europe "situla art is weak and sometimes quaint", and "in essence not of Europe".[59]

Except for the Italian Benvenuti Situla, men are hairless, with "funny hats, dumpy bodies and big heads", though often shown looking cheerful in an engaging way. The Benevenuti Situla is also unusual in that it seems to show a specific story.[60]

-

Late Halstatt gold collar from Austria, c. 550 BC

-

Gold shoe plaques from Hochdorf

-

Dagger with gold foil from Hochdorf

-

Replica of the Warrior of Hirschlanden

-

Armband with engraved decoration

-

Bull from Býčí skála Cave, Czech Republic[37]

-

Detail from the Vače situla, Slovenia

-

Wagon model from Frög, Austria

-

Drinking horn from Tuttlingen, Germany

-

Bronze recliner from Hochdorf

-

Pottery from Hegau, Germany

-

Ceramic vessel from Donnerskirchen, Austria

-

Pottery from Hungary, 7th century BC.[61]

Geography

Two culturally distinct areas, an eastern and a western zone are generally recognised.[62] There are distinctions in burial rites, the types of grave goods, and in artistic style. In the western zone, members of the elite were buried with sword (HaC) or dagger (HaD), in the eastern zone with an axe.[52] The western zone has chariot burials. In the eastern zone, warriors are frequently buried with helmet and a plate armour breastplate.[1] Artistic subjects with a narrative component are only found in the east, in both pottery and metalwork.[63] In the east the settlements and cemeteries can be larger than in the west.[52]

The approximate division line between the two subcultures runs from north to south through central Bohemia and Lower Austria at about 14 to 15 degrees eastern longitude, and then traces the eastern and southern rim of the Alps to Eastern and Southern Tyrol.[citation needed]

Western Hallstatt zone

Taken at its most generous extent, the western Hallstatt zone includes:

- northeastern France: Champagne-Ardenne, Lorraine, Alsace

- northern Switzerland: Swiss plateau

- Southern Germany: much of Swabia and Bavaria

- western Czech Republic: Bohemia

- western Austria: Vorarlberg, Tyrol, Salzkammergut

More peripheral areas were:

- Central and North Italy: Po valley, Liguria, Venetia, Marche, Abruzzo, Friuli

- northern, western and central Spain: Galicia, Asturias, Extremadura, Castile, Cantabria

- northern and north-central Portugal: Minho, Douro, Tras-os-Montes, Beira Alta

While Hallstatt is regarded as the dominant settlement of the western zone, a settlement at the Burgstallkogel in the central Sulm valley (southern Styria, west of Leibnitz, Austria) was a major centre during the Hallstatt C period. Parts of the huge necropolis (which originally consisted of more than 1,100 tumuli) surrounding this settlement can be seen today near Gleinstätten, and the chieftain's mounds were on the other side of the hill, near Kleinklein. The finds are mostly in the Landesmuseum Joanneum at Graz, which also holds the Strettweg Cult Wagon.

Eastern Hallstatt zone

The eastern Hallstatt zone includes:

- eastern Austria: Lower Austria, Upper Styria

- eastern Czech Republic: Moravia

- southwestern Slovakia: Danubian Lowland

- western Hungary: Little Hungarian Plain

- eastern Slovenia: Hallstatt Archaeological Site in Vače (at the border between Lower Styria and Lower Carniola regions), Novo Mesto

- northern Croatia: Hrvatsko Zagorje, Istria

- northern and central Serbia

- parts of southwestern Poland

- northern and western Bulgaria

Trade, cultural diffusion, and some population movements spread the Hallstatt cultural complex (western form) into Britain, and Ireland.

Genetics

A genetic study published in Nature in May 2018 examined the remains of a male and female buried at a Hallstatt cemetery near Litoměřice, Czech Republic between ca. 600 BC and 400 BC. The male was found to be a carrier of the paternal haplogroup R1b and the maternal haplogroup H6a1a. The female was a carrier of the maternal haplogroup HV0.[64]

A genetic study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America in June 2020 examined the remains of 5 individuals ascribed to either Hallstatt C or the early La Tène culture. The sample of Y-DNA extracted was determined to belong to haplogroup G2a, while the 5 samples of mtDNA extracted were determined to belong to the haplogroups K1a2a, J1c2o, H7d, U5a1a1 and J1c-16261.[65] The examined individuals of the Hallstatt culture and La Tène culture displayed genetic continuity with the earlier Bell Beaker culture, and carried about 50% steppe-related ancestry.[66]

A genetic study published in iScience in April 2022 examined 49 genomes from 27 sites in Bronze Age and Iron Age France. The study found evidence of strong genetic continuity between the two periods, particularly in southern France. The samples from northern and southern France were highly homogenous, with northern samples displaying links to contemporary samples form Great Britain and Sweden, and southern samples displaying links to Celtiberians. The northern French samples were distinguished from the southern ones by elevated levels of steppe-related ancestry. R1b was by far the most dominant paternal lineage, while H was the most common maternal lineage. The Iron Age samples resembled those of modern-day populations of France, Great Britain and Spain. The evidence suggested that the Celts of the Hallstatt culture largely evolved from local Bronze Age populations.[67]

See also

- Basarabi culture

- Bronze- and Iron-Age Poland

- Celtic warfare

- Iron Age sword

- Irschen

- Noric steel

- Prehistoric France

- Zollfeld

Citations

- ^ a b Megaw, 34

- ^ Paul Gleirscher: Von wegen Illyrer in Kärnten. Zugleich: von der Beständigkeit lieb gewordener Lehrmeinungen. In: Rudolfinum. Jahrbuch des Landesmuseums für Kärnten. 2006, p. 13–22 (online (PDF) in ZOBODAT).

- ^ "Kein Illyrikum in Norikum – Norisches Kulturmagazin".

- ^ Reinecke, Paul (1965). Mainzer Aufsätze zur Chronologie der Bronze- und Eisenzeit (in German). Bonn: Habelt. OCLC 12201992.

- ^ Eggers, Hans Jürgen (1955). "Zur absoluten Chronologie der römischen Kaiserzeit im Freien Germanien". Jahrbuch des römisch-germanischen Zentralmuseums (in German). 2. Mainz: 192–244. doi:10.11588/jrgzm.1955.0.31095.

- ^ Paul Reinecke: Zur Chronologie der 2. Hälfte des Bronzealters in Süd- und Norddeutschland. Korrespondenzbl. d. Deutsch. Ges. f. Anthr., Ethn. u. Urgesch. 33, 1902, 17—22. 27—32.

- ^ Paul Reinecke: Chronologische Übersicht der vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Zeiten. Bayer. Vorgeschichtsfreund 1—2, 1921—1922, 18—25.

- ^ Otto Tischler: Über die Formen der Gewandnadeln (Fibeln) nach ihrer historischen Bedeutung. In: Zeitschrift für Anthropologie und Urgeschichte Baierns. 4 (1–2), 1881, S. 3–40.

- ^ Michael Friedrich, Hening Hilke: Dendrochronologische Untersuchung der Hölzer des hallstattzeitlichen Wagengrabes 8 aus Wehringen, Lkr. Augsburg und andere Absolutdaten zur Hallstattzeit. Bayerische Vorgeschichtsblätter, 60. München : Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1995.

- ^ a b Megaw, 26

- ^ McIntosh, 88

- ^ Koch

- ^ a b c d Megaw, 40

- ^ a b Megaw, 48–49

- ^ Ehret, D. (2008). "Das Ende des hallstattzeitlichen Bergbaus". In Kern, A.; Kowarik, K.; Rausch, A. W.; Reschreiter, H. (eds.). Salz-Reich. 7000 Jahre Hallstatt (in German). Wien: VPA 2. p. 159. ISBN 978-3-902421-26-5.

- ^ Megaw 25, 29

- ^ Chadwick, Nora (1970). The Celts. p. 30.

- ^ Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. pp. 89–102.

- ^ Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages - Addenda. p. 25.

- ^ Alfons Semler, Überlingen: Bilder aus der Geschichte einer kleinen Reichsstadt,Oberbadische Verlag, Singen, 1949, pp. 11–17, specifically 15.

- ^ a b c Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. pp. 93–100.

- ^ a b c Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages (PDF). p. 24.

- ^ "Celtophile," Ryan Setliff Online. Dec. 24, 2019. https://www.ryansetliff.online/#celtophile

- ^ Percivaldi, Elena (2003). I Celti: una civiltà europea. Giunti Editore. p. 82.

- ^ Leonelli, Valentina. La necropoli delle Acciaierie di Terni: contributi per una edizione critica (Cestres ed.). p. 33.

- ^ Farinacci, Manlio. Carsulae svelata e Terni sotterranea. Associazione Culturale UMRU - Terni.

- ^ Megaw, 39–41

- ^ Fichtl, Stephan (2018). "Urbanization and oppida". In Haselgrove, Colin; Rebay-Salisbury, Katharina; Wells, Peter (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the European Iron Age. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199696826.013.13. ISBN 978-0-19-969682-6.

- ^ Fernández-Götz, Manuel; Ralston, Ian (2017). "The Complexity and Fragility of Early Iron Age Urbanism in West-Central Temperate Europe". Journal of World Prehistory. 30 (3): 259–279. doi:10.1007/s10963-017-9108-5. S2CID 55839665.

- ^ Zamboni, Lorenzo; Fernández-Götz, Manuel; Metzner-Nebelsick, Carola, eds. (2020). Crossing the Alps:Early Urbanism between Northern Italy and Central Europe (900-400 BC). Sidestone Press. ISBN 9789088909610.

- ^ Fernández-Götz, Manuel (2018). "Urbanization in Iron Age Europe: Trajectories, Patterns, and Social Dynamics". Journal of Archaeological Research. 26 (2): 117–162. doi:10.1007/s10814-017-9107-1.

- ^ Krausse, Dirk; Fernández-Götz, Manuel (2012). "Heuneburg: First city north of the Alps". Current World Archaeology. 55: 28–34.

- ^ Megaw, 39–43

- ^ Hansen, Leif; Krausse, Dirk; Tarpini, Roberto (2020). "Fortifications of the Early Iron Age in the surroundings of the Princely Seat of Heuneburg". In Delfino, Davide; Coimbra, Fernando; Cardoso, Daniela; Cruz, Gonçalo (eds.). Late Prehistoric Fortifications in Europe: Defensive, Symbolic and Territorial Aspects from the Chalcolithic to the Iron Age. Archaeopress. pp. 113–122.

- ^ Die Alte Burg bei Langenenslingen - Ein keltischer Kultplatz? (2021).

- ^ Fernández-Götz, Manuel (2018). "Urbanization in Iron Age Europe: Trajectories, Patterns, and Social Dynamics". Journal of Archaeological Research. 26 (2): 117–162. doi:10.1007/s10814-017-9107-1.

- ^ a b Megaw, 28

- ^ Megaw, 41–43, 45–47

- ^ Megaw, 25-30; 39–47

- ^ a b Hansen, Svend (2019). "The Hillfort of Teleac and Early Iron in Southern Europe". In Hansen, Svend; Krause, Rüdiger (eds.). Bronze Age Fortresses in Europe. Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn. p. 204.

- ^ Harding, D.W. (2007). The Archaeology of Celtic Art. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 9781134264643.

- ^ Jope, Martyn (1995). "The social implications of Celtic art: 600 BC to 600 AD". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. p. 400. ISBN 9781135632434.

- ^ Sandars, 209

- ^ Wells, Peter (1995). "Resources and Industry". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. p. 218. ISBN 9781135632434.

- ^ "East Lothian's Broxmouth fort reveals edge of steel". BBC News. 15 January 2014.

- ^ a b Piggot, Stuart (1995). "Wood and the Wheelwright". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. p. 325. ISBN 9781135632434.

- ^ Megaw, 43–44

- ^ Jope, Martyn (1995). "The social implications of Celtic art: 600 BC to 600 AD". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. pp. 400–401. ISBN 9781135632434.

- ^ Piggot, Stuart (1995). "Wood and the Wheelwright". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. p. 322. ISBN 9781135632434.

- ^ Chaume, Bruno (2011). Vix (Côte-d'Or), une résidence princière au temps de la splendeur d'Athènes. DRAC Bourgogne - Service Régional de l’Archéologie. p. 6.

- ^ "Char de la Côte-Saint-André". lugdunum.grandlyon.com.

- ^ a b c Megaw, 30

- ^ Megaw, Chapter 1; Laing, chapter 2

- ^ Megaw, 33-34

- ^ Megaw, 39-45

- ^ Megaw, 34-39; Sandars, 223-225

- ^ Megaw, 37

- ^ Sandars, 223-224

- ^ Sandars, 225, quoted

- ^ Sandars, 224

- ^ Megaw, 30–32

- ^ Koch; Kossack (1959); N. Müller-Scheeßel, Die Hallstattkultur und ihre räumliche Differenzierung. Der West- und Osthallstattkreis aus forschungsgeschichtlicher Sicht (2000)

- ^ Megaw, 30–39

- ^ Damgaard et al. 2018.

- ^ Brunel et al. 2020, Dataset S1, Rows 215-219.

- ^ Brunel et al. 2020, p. 5.

- ^ Fischer et al. 2022.

Sources

- Barth, F.E., J. Biel, et al. Vierrädrige Wagen der Hallstattzeit ("The Hallstatt four-wheeled wagons" at Mainz). Mainz: Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum; 1987. ISBN 3-88467-016-6

- Brunel, Samantha; et al. (June 9, 2020). "Ancient genomes from present-day France unveil 7,000 years of its demographic history". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (23). National Academy of Sciences: 12791–12798. doi:10.1073/pnas.1918034117. PMC 7293694. PMID 32457149.

- Damgaard, P. B.; et al. (May 9, 2018). "137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes". Nature. 557 (7705): 369–373. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..369D. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2. hdl:1887/3202709. PMID 29743675. S2CID 13670282. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Fischer, Claire-Elise; et al. (2022). "Origin and mobility of Iron Age Gaulish groups in present-day France revealed through archaeogenomics". iScience. 25 (4). Cell Press: 104094. Bibcode:2022iSci...25j4094F. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2022.104094. PMC 8983337. PMID 35402880.

- Leskovar, Jutta (2006). "Hallstat [2] the Hallstat culture". In Koch, John T (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- Laing, Lloyd and Jenifer. Art of the Celts, Thames and Hudson, London 1992 ISBN 0-500-20256-7

- McIntosh, Jane, Handbook to Life in Prehistoric Europe, 2009, Oxford University Press (USA), ISBN 9780195384765

- Megaw, Ruth and Vincent, Celtic Art, 2001, Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-28265-X

- Sandars, Nancy K., Prehistoric Art in Europe, Penguin (Pelican, now Yale, History of Art), 1968 (nb 1st edn.)

Further reading

- Kristinsson, Axel (2010), Expansions: Competition and Conquest in Europe since the Bronze Age, Reykjavík: Reykjavíkur Akademían, ISBN 978-9979-9922-1-9, retrieved 10 October 2011

Documentary

- Klaus T. Steindl: MYTHOS HALLSTATT - Dawn of the Celts. TV-Documentary subjecting new findings and state of archeological research (2018)[1][2][3]

External links

![]() Media related to Hallstatt culture at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hallstatt culture at Wikimedia Commons

- ^ Hallstatt-forschung (2018-11-08). "STIEGEN-BLOG Archäologische Forschung Hallstatt: Mythos Hallstatt - Eine Dokumentation von Terra Mater". STIEGEN-BLOG Archäologische Forschung Hallstatt. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ Nolf, Markus. "Dokumentarfilm "Terra Mater: Mythos Hallstatt"". www.uibk.ac.at (in German). Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ COMPANY. "Mystery of the Celtic Tomb". Terra Mater Factual Studios (in German). Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- Archaeological cultures of Central Europe

- Archaeological cultures of Southeastern Europe

- Archaeological cultures of Southern Europe

- Archaeological cultures of Southwestern Europe

- Archaeological cultures of Western Europe

- Archaeological cultures of West Asia

- Iron Age cultures of Europe

- Celtic archaeological cultures

- Iron Age of Slovenia

- Archaeological cultures in Austria

- Archaeological cultures in Belgium

- Archaeological cultures in Bulgaria

- Archaeological cultures in Croatia

- Archaeological cultures in the Czech Republic

- Archaeological cultures in England

- Archaeological cultures in France

- Archaeological cultures in Germany

- Archaeological cultures in Hungary

- Archaeological cultures in Portugal

- Archaeological cultures in Romania

- Archaeological cultures in Serbia

- Archaeological cultures in Slovakia

- Archaeological cultures in Slovenia

- Archaeological cultures in Spain

- Archaeological cultures in Switzerland

- Archaeological cultures in Turkey

- World Heritage Sites in Austria

- 8th-century BC establishments

- 6th-century BC disestablishments

- States and territories established in the 8th century BC

- States and territories disestablished in the 6th century BC

![Sword hilt inlaid with ivory and amber.[16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a6/Alice_Schumacher_PA_NHM_Wien_Abb_Salz-Reich_2008_Seite_131_1.jpg/130px-Alice_Schumacher_PA_NHM_Wien_Abb_Salz-Reich_2008_Seite_131_1.jpg)

![Cult wagon from La Côte-Saint-André, France.[51]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d1/Char-gaulois-d-apparat.jpg/130px-Char-gaulois-d-apparat.jpg)

![Bull from Býčí skála Cave, Czech Republic[37]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/NHM_-_Byci_Skala_Stier.jpg/130px-NHM_-_Byci_Skala_Stier.jpg)