Samarkand

39°39′15″N 66°57′35″E / 39.65417°N 66.95972°E

سمرقند Samarkand

Samarqand / Самарқанд | |

|---|---|

View of the Registan | |

| Country | |

| Province | Samarqand Province |

| Elevation | 702 m (2,303 ft) |

| Population (2008) | |

| • City | 596,300 |

| • Urban | 643,970 |

| • Metro | 708,000 |

Samarkand (Tajik: Самарқанд; Persian: سمرقند; Uzbek: Samarqand; from Sogdian: "Stone Fort" or "Rock Town") is the second-largest city in Uzbekistan and the capital of Samarqand Province. The city is most noted for its central position on the Silk Road between China and the West, and for being an Islamic centre for scholarly study. In the 14th century it became the capital of the empire of Timur (Tamerlane) and is the site of his mausoleum (the Gur-e Amir). The Bibi-Khanym Mosque remains one of the city's most notable landmarks. The Registan was the ancient center of the city.

In 2001, UNESCO added the city to its World Heritage List as Samarkand – Crossroads of Cultures.

Etymology

The city was known by an abbreviated name of Marakanda when Alexander the Great took it in 332BC. There are various theories of how Marakanda evolved into Samarkanda/Samarkan. One derives the name from the Old Persian asmara, "stone", "rock", and Sogdian kand, "fort", "town".[1] Others less convincingly derive the name from the old Turkic "Semiz-Kent" meaning "Rich City".[citation needed]. Since the name Marakanda was already in existence 2300 years ago and long before anyone had heard of Turks in that region of Transoxiana, this version is likely a folk etymology.

Population

The population of Samarkand grew from 134,346 in 1939[2] to 384,000 in 2005. Around 10 percent of Samarkand population is Tajik and speak Persian.[citation needed]

History

Along with Bukhara,[3] Samarkand is one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world, prospering from its location on the trade route between China and the Mediterranean (Silk Road). At times Samarkand has been one of the greatest cities of Central Asia.

Early history

Founded circa 700 BC by the Sogdians, Samarkand has been one of the main centres of Persian civilization from its early days. It was already the capital of the Sogdian satrapy under the Achaemenid dynasty of Persia when Alexander the Great conquered it in 329 BC. The Greeks referred to Samarkand as Maracanda.[4]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Bibi-Khanym Mausoleum | |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv |

| Reference | 603 |

| Inscription | 2001 (25th Session) |

Although a Persian-speaking region, it was not united politically with Iran most of the times between the disintegration of the Seleucid Empire and the Arab conquest (except at the time of early Sassanids, such as Shapur I).[5] In the 6th century it was within the domain of the Turkic kingdom of the Göktürks.[6]

At the start of the 8th century Samarkand came under Arab control. Under Abbasid rule, the legend goes,[7] the secret of papermaking was obtained from two Chinese prisoners from the Battle of Talas in 751, which led to the first paper mill in the Islamic world being founded in Samarkand. The invention then spread to the rest of the Islamic world, and from there to Europe.

From the 6th to the 13th century it grew larger and more populous than modern Samarkand[citation needed] and was controlled by the Western Turks, Arabs (who converted the area to Islam), Persian Samanids, Kara-Khanid Turks, Seljuk Turks, Kara-Khitan, and Khorezmshah before the Mongols arrived in 1220.

Although Genghis Khan "did not disturb the inhabitants [of the city] in any way," according to Juvaini he killed all who took refuge in the citadel and the mosque. He also pillaged the city completely and conscripted 30,000 young men along with 30,000 craftsmen. Samarkand suffered at least one other Mongol sack by Khan Baraq to get treasure he needed to pay an army. The town took many decades to recover from these disasters.

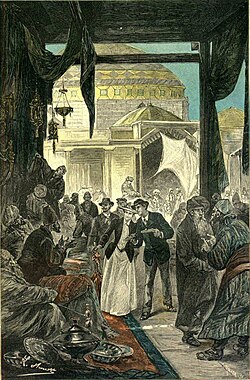

The Travels of Marco Polo, where Polo records his journey along the Silk Road, describes Samarkand as a "a very large and splendid city..." Here also is related the story of a Christian church in Samarkand, which miraculously remained standing after a portion of its central supporting column was removed.

14th century

In 1365, a revolt against Mongol control occurred in Samarkand.[8]

In 1370, Timur the Lame decided to make Samarkand the capital of his empire, which extended from India to Turkey. During the next 35 years he built a new city and populated it with artisans and craftsmen from all of the places he had conquered. Timur gained a reputation as a patron of the arts and Samarkand grew to become the centre of the region of Transoxiana. During this time the city had a population of about 150,000.[9]

15th century

Between 1424 and 1429, the great astronomer Ulugh Beg built the Samarkand Observatory. The sextant was 11 metres long and once rose to the top of the surrounding three-storey structure, although it was kept underground to protect it from earthquakes. Calibrated along its length, it was the world’s largest 90-degree quadrant at the time.[10] However, the observatory was destroyed by religious fanatics in 1449.[10]

Modern history

This article needs to be updated. (November 2011) |

In 1500 the Uzbek nomadic warriors took control of Samarkand.[9] The Shaybanids emerged as the Uzbek leaders at or about this time.

In the second quarter of 16th century, the Shaybanids moved their capital to Bukhara and Samarkand went into decline. After an assault by the Persian king, Nadir Shah, the city was abandoned in the 18th century, about 1720 or a few years later.[11]

From 1599 to 1756, Samarkand was ruled by the Ashtarkhanid dynasty of Bukhara.

From 1756 to 1868, Samarkand was ruled by the Manghyt emirs of Bukhara.[2]

The city came under Russian rule after the citadel had been taken by a force under Colonel Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman in 1868. Shortly thereafter the small Russian garrison of 500 men were themselves besieged. The assault, which was led by Abdul Malik Tura, the rebellious elder son of the Bukharan Emir, and Bek of Shahrisabz, was beaten off with heavy losses. Alexander Abramov, became the first Governor of the Military Okrug which the Russians established along the course of the Zeravshan River, with Samarkand as the administrative centre. The Russian section of the city was built after this point, largely to the west of the old city.

In 1886 the city became the capital of the newly formed Samarkand Oblast of Russian Turkestan and grew in importance still further when the Trans-Caspian railway reached the city in 1888. It became the capital of the Uzbek SSR in 1925 before being replaced by Tashkent in 1930.

Main sights

- The Registan, one of the most relevant examples of Islamic architecture. It consists of three separate buildings:

- Madrasa of Ulugh Beg (1417–1420)

- Sher-Dor Madrasah (Lions Gate) (1619–1635/36).

- Tilya-Kori Madrasah (1647–1659/60).

- Bibi-Khanym Mosque (replica)

- Gur-e Amir Mausoleum (1404)

- Observatory of Ulugh Beg (1428–1429)

- Shah-i-Zinda necropolis

- Historical site of Afrasiyab (13th–7th centuries BC)

Climate

Samarkand features a semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk) with hot, dry summers and relatively wet, cool winters. July and August are the hottest months of the year with temperatures reaching, and exceeding, 40 °C (104 °F). Most of the sparse precipitation is received from December through April.[12]

| Climate data for Samarkand | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

20.8 (69.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.8 (92.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

27.9 (82.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

14.9 (58.8) |

9.2 (48.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

2.2 (36.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

14.5 (58.1) |

19.5 (67.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

26.2 (79.2) |

24.2 (75.6) |

19.3 (66.7) |

12.7 (54.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

3.3 (37.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.3 (26.1) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

12.7 (54.9) |

16.4 (61.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

15.9 (60.6) |

11.2 (52.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

7.4 (45.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 44 (1.7) |

39 (1.5) |

71 (2.8) |

63 (2.5) |

33 (1.3) |

4 (0.2) |

4 (0.2) |

0 (0) |

4 (0.2) |

24 (0.9) |

28 (1.1) |

41 (1.6) |

355 (14.0) |

| Source: Hong Kong Observatory[13] | |||||||||||||

Notable people

- Amoghavajra, 8th century Buddhist monk, translator of Vajrayana scripture, figure in the Tang court, remembered as one of the three founders of Chinese esoteric Buddhism.

- Abu Mansur Maturidi, Sunni theologist of the 10th century

- Omar Khayyám, poet and mathmatician of the 11th century

- Nizami Aruzi Samarqandi, poet and writer of the 12th century

- Suzani Samarqandi, poet of the 12th century

- Najib ad-Din-e-Samarqandi, scholar of the 13th century

- Jamshīd al-Kāshī, astronomer and mathmatician of the 15th century

- Shams al-Dīn al-Samarqandī, scholar

- Nawab Khwaja Abid Siddiqi and Nawab Qaziuddin Siddiqi, grandfather and father of Mir Qamaruddin Siddiqi Asaf Jah I whose dynasty ruled Hyderabad Deccan for seven generations from 1724 to 1951

- Islam Karimov, 1st President of Uzbekistan.

Also said to be the place of death of Muhammad b. Isma'il al-Bukhari, one of the six prominent collectors of hadith of Sunni Islam. See Sahih Bukhari

Popular culture

Fiction

- Chapters 37 and 38 of Jin Yong's Wuxia novel The Legend of the Condor Heroes briefly portray the Mongolian siege of Samarkand in March 1220.

- Samarkand is the title of a 1988 novel by Amin Maalouf, about Omar Khayyám's life.

- The Amulet of Samarkand is the first book in the Bartimaeus Trilogy written by Jonathan Stroud.

- The Road to Samarcand is one of Patrick O'Brian's early novels (1954) about an American teenage boy, the son of recently deceased missionary parents, who travels from China with a small party on the Silk Road en route to the West.

- In Corto Maltese graphical novels by Hugo Pratt one episode is titled "The Golden House of Samarkand"

- The fictional city of Zanarkand in the Final Fantasy series, used Samarkand as inspiration.[14]

- Samarkand is the name of a continent in the Fable fictional universe, though it is more based on Africa and the Orient than Central Asia.

- For part of the history espoused in Clive Barker's novel Galilee, the city of Samarkand is held as a shining light of humanity, and one of the characters longs to go there.[15]

- 'Trębacz z Samarkandy' (The Trumpeter of Samarkand) a short story by Ksawery Pruszyński set during the Second World War, inspired by a Polish legend.

- In The Venetian Betrayal, Samarkand was the world's most powerful city and the "cradle of civilization".

- The objective of the fourth mission in the Ghengis Khan campaign of the video game Age of Empires 2 is to destroy the city of Samarkand.

- Lord of Samarcand is a work of historical fiction by Robert E. Howard.

- An ice-world in Gridlinked, part of Neal Asher's Polity Universe.

- The location of the rose of the DeVirga World Map on the 39 clues.

Poetry, drama and film

- Samarkand can appear as an archetype of romantic exoticism, notably in the work by James Elroy Flecker: The Golden Journey to Samarkand (1913).

- In Islamic literature and discussions, Samarkand has taken on a semi-mythological status and is often cited as an ideal of Islamic philosophy and society, a place of justice, fairness, and righteous moderation.

- Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka, winner of the 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature, explores the metaphysical significance of the marketplace in a volume of poetry entitled Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known, 2002.

- Samarkand has a large featuring in the originally Russian film Day Watch, originally written by Sergei Lukyanenko as part of a Trilogy. Samarkand is the place where the fictional battle for the "Chalk of fate" takes place.

- The American musical Once Upon a Mattress features a character known as the Nightingale of Samarkand. The bird supposedly sings people to sleep.

Non-fiction

- Ibn Battuta, the Muslim 14th century traveler, spent time in Samarkand in the 1330s

- Murder in Samarkand by Craig Murray is a book about the UK Ambassador to Uzbekistan's experiences in this role, until he resigned over human rights abuses in the country in October 2004.

- In her 2010 memoir The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them[16] Elif Batuman writes three chapters about her experiences studying the Uzbek language as a graduate exchange student in Samarkand.

Music

- In 1972, Swedish composer Thorstein Bergman wrote "Om du någonsin kommer fram till Samarkand" ("If you ever reach Samarkand") made notable by Swedish singer Lill Lindfors in 1978.

- In 1977, the Italian singer and composer Roberto Vecchioni issued an LP titled Samarcanda.

- In 2004, violinist Lucia Micarelli released the album Music from a Farther Room, which includes the song "Samarkand".

- In 2008, the Norwegian singer and musician Odd Nordstoga released the album Pilegrim, which includes the song "I byen Samarkand" ("In the city of Samarkhand").

- In 2011, the Australian/British string quartet BOND released the album Play featuring the recording "Road to Samarkand".

- The Uzbek group Yalla made a song in Russian called "The Blue Domes of Samarkand".

In 2012, the Swedish singer Thåström released the album "Beväpna dig met vingar" which includes a song called "Samarkanda".

Sister cities

Boonton, USA

Boonton, USA Nishapur, Iran

Nishapur, Iran Bukhara, Uzbekistan

Bukhara, Uzbekistan Balkh, Afghanistan

Balkh, Afghanistan Merv, Turkmenistan

Merv, Turkmenistan Cuzco, Peru

Cuzco, Peru Lahore, Pakistan

Lahore, Pakistan Lviv, Ukraine

Lviv, Ukraine Kairouan, Tunisia

Kairouan, Tunisia Eskişehir, Turkey

Eskişehir, Turkey Istanbul, Turkey

Istanbul, Turkey İzmir, Turkey

İzmir, Turkey Khujand, Tajikistan

Khujand, Tajikistan Banda Aceh, Indonesia

Banda Aceh, Indonesia

See also

- Samarkand Airport

- Semerkand a monthly religious magazine published in Turkey, named after this city because Samarkand has long been a major centre for Islamic scholars.

References

- ^ Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features and Historic Sites (2nd edition ed.). London: McFarland. p. 330. ISBN 0-7864-2248-3.

Samarkand City, southeastern Uzbekistan. The city derives its name from that of the former Greek city here of Marakanda, captured by Alexander the Great in 329 B.C.. Its own name derives from the Old Persian asmara, "stone", "rock", and Sogdian kand, "fort", "town".

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Columbia-Lippincott Gazeteer. p. 1657

- ^ Vladimir Babak, Demian Vaisman, Aryeh Wasserman, Political organization in Central Asia and Azerbaijan: sources and documents, p.374

- ^ Columbia-Lippincott Gazeteer (New York: Comubia University Press, 1972 reprint) p. 1657

- ^ Guitty Azarpay (1980), Sogdian painting: the pictorial epic in Oriental art, Berkeley : University of California Press, page 16.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984) Vol. 16, p. 204

- ^ Quraishi, Silim "A survey of the development of papermaking in Islamic Countries", Bookbinder, 1989 (3): 29–36.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Ed., p. 204

- ^ a b Columbia-Lippincott Gazeteer, p. 1657

- ^ a b "Samarqand". Raw W Travels. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ Britannica. 15th Ed., p. 204

- ^ Samarkand.info. "Weather in Samarkand". Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ "Climatological Normals of Samarkand". Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ^ (2001) in Studio BentStuff: Final Fantasy X Ultimania Ω (in Japanese). DigiCube/Square Enix, 476. ISBN 4-88787-021-3.

- ^ Clive Barker, Galilee ISBN 0-00-617805-7rm

- ^ Batuman, Elif. "The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People who Read Them" Farrar, Straus and Giroux Paperbacks, February 2010. ISBN 978-0-374-53218-5.

Bibliography

- Alexander Morrison, Russian Rule in Samarkand 1868-1910: A Comparison with British India (Oxford, OUP, 2008) (Oxford Historical Monographs).

External links

- Samarkand – Silk Road Seattle Project, University of Washington

- The history of Samarkand, according to Columbia University's Encyclopædia Iranica