Upton Sinclair

Upton Sinclair | |

|---|---|

| |

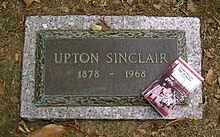

| Born | Upton Beall Sinclair, Jr. September 20, 1878 Baltimore, Maryland, United States |

| Died | November 25, 1968 (aged 90) Bound Brook, New Jersey, United States |

| Occupation | Novelist, writer, journalist, political activist, politician |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse | Meta Fuller (1902–11) Mary Craig Kimbrough, (1913–61) Mary Elizabeth Willis (1961–67) |

| Signature | |

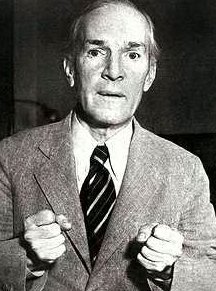

Upton Beall Sinclair, Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer of nearly 100 books and other works across a number of genres. Sinclair's work was well-known and popular in the first half of the twentieth century, and he won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1943.

In 1906, Sinclair acquired particular fame for his classic muckraking novel, The Jungle, which exposed conditions in the U.S. meat packing industry, causing a public uproar that contributed in part to the passage a few months later of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act.[1] In 1919, he published The Brass Check, a muckraking exposé of American journalism that publicized the issue of yellow journalism and the limitations of the “free press” in the United States. Four years after publication of The Brass Check, the first code of ethics for journalists was created.[2] Time magazine called him "a man with every gift except humor and silence."[3] He is remembered for writing the famous line: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it."

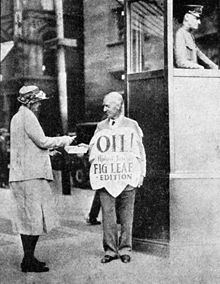

Many of his novels can be read as historical works. Writing during the Progressive Era, Sinclair describes the world of industrialized America from both the working man's point of view and the industrialist. Novels like King Coal (1917), The Coal War (published posthumously), Oil! (1927) and The Flivver King (1937) describe the working conditions of the coal, oil and auto industries at the time.

He attacked J. P. Morgan, whom many regarded as a hero for ending the Panic of 1907, saying that he had engineered the crisis in order to acquire a bank.[citation needed]The Flivver King describes the rise of Henry Ford, his "wage reform" and the company's Sociological Department to his decline into antisemitism as publisher of "The Dearborn Independent". King Coal confronts John D. Rockefeller Jr. and his role in the 1913 Ludlow Massacre in the coal fields of Colorado.

Sinclair was an outspoken socialist and ran unsuccessfully for Congress as a nominee from the Socialist Party. He was also the Democratic Party candidate for Governor of California during the Great Depression, running under the banner of the End Poverty in California campaign, but was defeated in the 1934 elections.

Early life and education

Sinclair was born in Baltimore, Maryland, to Upton Beall Sinclair and Priscilla Harden. His father was a liquor salesman whose alcoholism shadowed his son's childhood. Priscilla Harden Sinclair was a strict Episcopalian who disliked alcohol, tea, and coffee. As a child, Sinclair slept either on sofas or cross-ways on his parents' bed. When his father was out for the night, he would sleep alone in the bed with his mother.[4] Sinclair did not get along with her when he became older because of her strict rules and refusal to allow him independence. Sinclair later told his son, David, that around Sinclair's 16th year, he decided not to have anything to do with his mother, staying away from her for 35 years because an argument would start if they met.[5] His mother's family was highly affluent: her parents were very prosperous in Baltimore, and her sister married a millionaire. Sinclair had wealthy maternal grandparents with whom he often stayed. This gave him insight into how both the rich and the poor lived during the late nineteenth century. Living in two social settings affected him and greatly influenced his books. Upton Beall Sinclair, Sr. was from a highly respected family in the South, but due to the Civil War and disruptions of the labor system during the Reconstruction era, as well as an extended agricultural depression, the family's wealth evaporated, and the family was financially ruined.

As he was growing up, Upton's family moved frequently as his father was not successful in his career. He became close with Reverend William Wilmerding Moir. Moir specialized in sexual abstinence and taught his beliefs to Sinclair. He was taught to "avoid the subject of sex." Sinclair was to report to Moir monthly regarding his abstinence. Despite their close relationship, Sinclair identified as agnostic.[6] Sinclair, Jr. developed a love for reading at age five years. He read every book his mother owned for a deeper understanding of the world. He did not start school until he was ten years old. He was deficient in math and worked hard to catch up quickly because of his embarrassment.[6] In 1888, the Sinclair family moved to Queens, New York, where his father sold shoes. Sinclair, Jr. entered the City College of New York five days before his 14th birthday,[7] on September 15, 1892.[8] He wrote jokes, dime novels, and magazine articles in boys' weekly and pulp magazines to pay for his tuition.[9] He was able to move his parents to an apartment when he was seventeen years old with that income.[10]

He graduated in June 1897 and studied for a time at Columbia University.[11] His major was Law, but he was more interested in writing, and he learned several languages including Spanish, German and French. He paid the one-time enrollment fee to be able to learn a variety of different things. He would sign up for a class and then later drop it.[12] He again supported himself through college by writing boys' adventure stories and jokes. He also sold ideas to cartoonists.[10] Using stenographers, he wrote up to 8,000 words of pulp fiction per day. His only complaint about his educational experience was that it failed to educate him about socialism.[13] After leaving Columbia, he wrote four books in the next four years; they were commercially unsuccessful though critically well-received: King Midas (1901), Prince Hagen (1902), The Journal of Arthur Stirling (1903), and a Civil War novel titled Manassas (1904).[citation needed]

Career

Upton Sinclair imagined himself a poet and dedicated his time to writing poetry initially.[14]

In 1904, Sinclair spent seven weeks in disguise, working undercover in Chicago's meatpacking plants to research his novel, The Jungle (1906), a political exposé that addressed conditions in the plants as well as the lives of poor immigrants. When it was published two years later, it became a bestseller.

With the income from The Jungle, Sinclair founded the utopian Helicon Home Colony in Englewood, New Jersey (Helicon Home Colony was a white-only space which "explicitly banned jewish bolsheviks and less publicly banned Jews"[15]). He ran as a Socialist candidate for Congress.[16][17] The colony burned down under suspicious circumstances within a year.[18]

In the spring of 1905, Sinclair issued a call for the formation of a new organization, a group to be called the Intercollegiate Socialist Society.[19]

In 1913-1914, Sinclair made three trips to the coal fields of Colorado which led him to write King Coal and caused him to begin work on the larger, more historical The Coal War. In 1914, Sinclair helped organize demonstrations in New York City against Rockefeller at the Standard Oil offices. The demonstrations touched off more actions by the IWW and the Mother Earth group, a loose association of anarchists and IWW members, in Rockefeller's hometown of Tarrytown.[20]

The Sinclairs moved to California in the 1920s and lived there for nearly four decades. During his years with his second wife, Mary Craig, Sinclair wrote or produced several films. Recruited by Charlie Chaplin, Sinclair and Mary Craig produced Eisenstein's ¡Qué viva México! in 1930–32.[21]

Other interests

Aside from his political and social writings, Sinclair took an interest in occult phenomena and experimented with telepathy. His book Mental Radio (1930) included accounts of his wife Mary's telepathic experiences and ability.[22][23] William McDougall read the book and wrote an introduction to it, which led him to establish the parapsychology department at Duke University.[citation needed]

Political career

Sinclair broke with the Socialist party in 1917 and supported the war effort. By the 1920s, however, he had returned to the fold.

In the 1920s, the Sinclairs moved to Monrovia, California, near Los Angeles, where Sinclair founded the state's chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Wanting to pursue politics, he twice ran unsuccessfully for United States Congress on the Socialist ticket: in 1920 for the House of Representatives and in 1922 for the Senate. He was the party candidate for governor California in 1930, winning nearly 50,000 votes.

During this period, Sinclair was also active in radical politics in Los Angeles. For instance, in 1923, to support the challenged free speech rights of Industrial Workers of the World, Sinclair spoke at a rally during the San Pedro Maritime Strike, in a neighborhood now known as Liberty Hill. He began to read from the Bill of Rights and was promptly arrested, along with hundreds of others, by the LAPD. The arresting officer proclaimed: "We'll have none of that Constitution stuff".[24]

In 1934, Sinclair ran in the California gubernatorial election as a Democrat. Sinclair's platform, known as the End Poverty in California movement (EPIC), galvanized the support of the Democratic Party, and Sinclair gained its nomination.[25] Gaining 879,000 votes made this his most successful run for office, but incumbent Governor Frank F. Merriam defeated him by a sizable margin,[26] gaining 1,138,000 votes.[27][28]

Sinclair's plan to end poverty quickly became a controversial issue under the pressure of numerous migrants to California fleeing the Dust bowl. Conservatives considered his proposal an attempted communist takeover of their state and quickly opposed him, using propaganda to portray Sinclair as a staunch communist. Sinclair had been a member of the Socialist Party from 1902 to 1934, when he became a Democrat, though always considering himself a Socialist in spirit.[29] The Socialist party in California and nationwide refused to allow its members to be active in any other party including the Democratic Party and expelled him, along with socialists who supported his California campaign. The expulsions destroyed the Socialist party in California.[30]

At the same time, American and Soviet communists disassociated themselves from him, considering him a capitalist.[31] Science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein was deeply involved in Sinclair's campaign, although he attempted to move away from the stance later in his life.[32]

After his loss to Merriam, Sinclair abandoned EPIC and politics to return to writing. In 1935, he published I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked, in which he described the techniques employed by Merriam's supporters, including the then popular Aimee Semple McPherson, who vehemently opposed socialism and what she perceived as Sinclair's modernism. Sinclair's line from this book "It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it" has become well known and was for example quoted by Al Gore in An Inconvenient Truth.[33]

Of his gubernatorial bid, Sinclair remarked in 1951:

The American People will take Socialism, but they won't take the label. I certainly proved it in the case of EPIC. Running on the Socialist ticket I got 60,000 votes, and running on the slogan to 'End Poverty in California' I got 879,000. I think we simply have to recognize the fact that our enemies have succeeded in spreading the Big Lie. There is no use attacking it by a front attack, it is much better to out-flank them.[34]

Personal life

In April 1900, Sinclair went to Lake Massawippi in Quebec to work on a novel. He had a small cabin rented for three months and then he moved to a farmhouse.[6] It was here he and his future wife, Meta Fuller, became close. She was three years younger than him and had aspirations of being more than a housewife. Sinclair gave her direction as to what to read and learn.[6] Meta had been a childhood friend whose family was one of the First Families of Virginia. Each had warned the other about themselves and would later bring that up in arguments. They married October 18, 1900.[6] They used abstinence as their main form of birth control. Meta became pregnant with a child shortly after they married and attempted to abort it multiple times.[6] The child was born on December 1, 1901, and named David.[35][page needed] Meta and her family tried to get Sinclair to give up writing and get "a job that would support his family."[14] Around 1911, Meta left Sinclair for the poet Harry Kemp, later known as the "Dunes Poet" of Provincetown, Massachusetts.

In 1913, Sinclair married Mary Craig Kimbrough (1883–1961), a woman from an elite Greenwood, Mississippi, family. She had written articles and a book on Winnie Davis, the daughter of Confederate States of America President Jefferson Davis. He met her when she attended a lecture by him about The Jungle.[36] In the 1920s, the Sinclair couple moved to California. They were married until her death in 1961.

Sinclair married again, to Mary Elizabeth Willis (1882–1967).[37]

Sinclair was opposed to sex outside of marriage and he viewed marital relations as necessary only for procreation.[38] He told his first wife Meta that only the birth of a child gave marriage "dignity and meaning".[39] Despite his beliefs, he had an adulterous affair with Anna Noyes during his marriage to Meta. He wrote a novel about the affair called Love's Progress, a sequel to Love's Pilgrimage. It was never published. [40] His wife next had an affair with John Armistead Collier, a theology student from Memphis; they had a son together named Ben.[41]

In his novel, Mammonart, he suggested that Christianity was a religion that favored the rich and promoted a drop of standards. He was against it.[42]

Late in life Sinclair, with his third wife Mary Willis, moved to Buckeye, Arizona. They returned East to Bound Brook, New Jersey. Sinclair died there in a nursing home on November 25, 1968, a year after his wife.[43] He is buried in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C., next to Willis.

Writing

Sinclair devoted his writing career to documenting and criticizing the social and economic conditions of the early twentieth century in both fiction and non-fiction. He exposed his view of the injustices of capitalism and the overwhelming effects of poverty among the working class. He also edited collections of fiction and non-fiction.

The Jungle

His novel based on the meatpacking industry in Chicago, The Jungle, was first published in serial form in the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason, from February 25, 1905 to November 4, 1905. It was published as a book by Doubleday in 1906.[44]

Sinclair had spent about six months investigating the Chicago meatpacking industry for Appeal to Reason, the work which inspired his novel. He intended to "set forth the breaking of human hearts by a system which exploits the labor of men and women for profit".[45] The novel featured Jurgis Rudkus, a Lithuanian immigrant who works in a meat factory in Chicago, his teenage wife Ona Lukoszaite, and their extended family. Sinclair portrays their mistreatment by Rudkus' employers and the wealthier elements of society. His descriptions of the unsanitary and inhumane conditions that workers suffered served to shock and galvanize readers. Jack London called Sinclair's book "the Uncle Tom's Cabin of wage slavery".[46] Domestic and foreign purchases of American meat fell by half.[47]

Sinclair wrote in Cosmopolitan Magazine in October 1906 about The Jungle: "I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach."[3] The novel brought public lobbying for Congressional legislation and government regulation of the industry, including passage of the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act.[48][49] At the time, President Theodore Roosevelt characterized Sinclair as a "crackpot",[50] writing to William Allen White, "I have an utter contempt for him. He is hysterical, unbalanced, and untruthful. Three-fourths of the things he said were absolute falsehoods. For some of the remainder there was only a basis of truth."[51] After reading The Jungle, Roosevelt agreed with some of Sinclair's conclusions but was opposed to legislation that he considered "socialist." He said, "Radical action must be taken to do away with the efforts of arrogant and selfish greed on the part of the capitalist."[52]

The Brass Check

In The Brass Check (1919), Sinclair made a systematic and incriminating critique of the severe limitations of the “free press” in the United States. Among the topics covered is the use of yellow journalism techniques created by William Randolph Hearst. Sinclair called The Brass Check "the most important and most dangerous book I have ever written."[53]

Sylvia novels

- Sylvia (1913) was a novel about a Southern girl. In her autobiography, Mary Craig Sinclair said she had written the book based on her own experiences as a girl, and Upton collaborated with her. [note 1][54] She asked him to publish it under his name.[55] When it appeared in 1913, the New York Times called it "the best novel Mr. Sinclair has yet written–so much the best that it stands in a class by itself."[56]

- Sylvia's Marriage (1914), Craig and Sinclair collaborated on a sequel, also published by John C. Winston Company under Upton Sinclair's name.[57] In his 1962 autobiography, Upton Sinclair wrote: "[Mary] Craig had written some tales of her Southern girlhood; and I had stolen them from her for a novel to be called Sylvia."[58]

I, Governor of California, and How I Ended Poverty

This was a novel he published in 1934 as a preface to running for office. He outlined his plans in it.[59]

Lanny Budd series

Between 1940 and 1953, Sinclair wrote a series of 11 novels featuring a central character named Lanny Budd. The son of an American arms manufacturer, Budd is portrayed as holding in the confidence of world leaders, and not simply witnessing events but often propelling them. As a sophisticated socialite, who mingles easily with people from all cultures and socioeconomic classes, Budd has been characterized as the antithesis of the stereotyped "Ugly American".[60]

Sinclair placed Budd within the important political events in the United States and Europe in the first half of the twentieth century. There was an actual company named the Budd Company which manufactured arms during World War II, founded by Edward G. Budd in 1912.

The novels were bestsellers upon publication and were published in translation, appearing in twenty-one countries. The third book in the series, Dragon's Teeth (1942), won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1943.[61] Out of print and nearly forgotten for years, ebook editions of the Lanny Budd series were published in 2016.[62]

The Lanny Budd series includes:

- World's End, 1940

- Between Two Worlds, 1941

- Dragon's Teeth, 1942

- Wide Is the Gate, 1943

- Presidential Agent, 1944

- Dragon Harvest, 1945

- A World to Win, 1946

- Presidential Mission, 1947

- One Clear Call, 1948

- O Shepherd, Speak!, 1949

- The Return of Lanny Budd, 1953

Other works

Sinclair was keenly interested in health and nutrition. He experimented with various diets, and with fasting. He wrote about this in his book, The Fasting Cure (1911), another bestseller.[63] He believed that periodic fasting was important for health, saying, "I had taken several fasts of ten or twelve days' duration, with the result of a complete making over of my health".[64]

Sinclair favored a raw food diet of predominantly vegetables and nuts. For long periods of time, he was a complete vegetarian, but he also experimented with eating meat. His attitude to these matters was fully explained in the chapter, “The Use of Meat,” in the above-mentioned book.[65]

Representation in popular culture

- Sinclair is featured as one of the main characters in Chris Bachelder's satirical novel, U.S.! (2005). Repeatedly, Sinclair is resurrected after his death and assassinated again, a "personification of the contemporary failings of the American left". He is portrayed as a quixotic reformer attempting to stir an apathetic American public to implement socialism in America.[66]

- Sinclair Lewis refers to Sinclair and his EPIC plan in Lewis' novel, It Can't Happen Here (1935).

- Joyce Carol Oates refers to Sinclair and his first wife, Meta, in her novel The Accursed (2013).

- Sinclair is extensively featured as a figure in Harry Turtledove's American Empire trilogy (2001-2003) as part of the Southern Victory Series, an alternate history in which the American Socialist Party succeeds in becoming a major force in U.S. politics. This follows two humiliating military defeats to the Confederate States, the United Kingdom, and France and the post-1882 collapse of the Republican Party, with former president Abraham Lincoln leading a large number of Liberal Republicans into the Socialist Party. Sinclair wins the 1920 and 1924 presidential elections and becomes the first Socialist President of the United States. He was also the 29th president in the timeline. On March 4, 1921, his inauguration attended by crowds of jubilant militants waving red flags. However, his policies as portrayed by Turtledove are not particularly radical. Sinclair served as president until 1929 when his Vice President Hosea Blackford is elected in 1928 and becomes the 30th president.

Films

- The Jungle (1914) is a silent film adaptation of the 1906 novel, with George Nash playing Jurgis Rudkus and Gail Kane playing Ona Lukozsaite. The film is considered lost.[67] Sinclair appears at the beginning and end of the film "as a form of endorsement."[68]

- The Wet Parade (1932) is a film adaptation of Sinclair's eponymous 1931 novel, directed by Victor Fleming and starring Robert Young, Myrna Loy, Walter Huston, and Jimmy Durante.

- The Walt Disney Company adapted The Gnomobile (1937) as an eponymous musical motion picture released in 1967.[69]

- Oil! (1927) was adapted as the film There Will Be Blood (2007), starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Paul Dano, and written, produced, and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson. The film received eight Oscar nominations and won two.[70]

In Quotes

"Our newspapers do not represent public interests, but private interests; they do not represent humanity, but property; they value a man, not because he is great, or good, or wise, or useful, but because he is wealthy, or of service to vested wealth." (Source: The Brass Check, p. 125)

"I was determined to get something done about the Condemned Meat Industry. I was determined to get something done about the atrocious conditions under which men, women and children were working the Chicago stockyards. In my efforts to get something done, I was like an animal in a cage. The bars of this cage were newspapers, which stood between me and the public; and inside the cage I roamed up and down, testing one bar after another, and finding them impossible to break." (Source: The Brass Check, p. 39)

"The social body to which we belong is at this moment passing through one of the greatest crises of its history . . . What if the nerves upon which we depend for knowledge of this social body should give us false reports of its condition?" (Source: The Brass Check, p. 9)

Works

Fiction

- Courtmartialed - 1898

- Saved By the Enemy - 1898

- The Fighting Squadron - 1898

- A Prisoner of Morro - 1898

- A Soldier Monk - 1898

- A Gauntlet of Fire - 1899

- Holding the Fort (story) - 1899

- A Soldier's Pledge - 1899

- Wolves of the Navy - 1899

- Springtime and Harvest - 1901, reissued the same year as King Midas

- The Journal of Arthur Stirling - 1903

- Off For West Point - 1903

- From Port to Port - 1903

- On Guard - 1903

- A Strange Cruise - 1903

- The West Point Rivals - 1903

- A West Point Treasure - 1903

- A Cadet's Honor - 1903

- Cliff, the Naval Cadet - 1903

- The Cruise of the Training Ship - 1903

- Prince Hagen - 1903

- Manassas: A Novel of the War - 1904, reissued in 1959 as Theirs be the Guilt

- A Captain of Industry - 1906

- The Jungle - 1906

- The Overman - 1907

- The Industrial Republic - 1907

- The Metropolis - 1908

- The Money Changers - 1908

- Samuel The Seeker - 1910

- Love's Pilgrimage - 1911

- Damaged Goods - 1913

- Sylvia - 1913

- Sylvia's Marriage - 1914

- King Coal - 1917

- Jimmie Higgins - 1919

- Debs and the Poets - 1920

- 100% - The Story of a Patriot - 1920

- The Spy - 1920

- The Book of Life - 1921

- They Call Me Carpenter: A Tale of the Second Coming - 1922

- The Millennium - 1924

- The Goslings A Study Of The American Schools - 1924

- Mammonart - 1925

- The Spokesman's Secretary - 1926

- Money Writes! - 1927

- Oil! - 1927

- Boston, 2 vols. - 1928

- Mountain City - 1930

- Roman Holiday - 1931

- The Wet Parade - 1931

- American Outpost - 1932

- The Way Out (novel) - 1933

- Immediate Epic - 1933

- The Lie Factory Starts - 1934

- The Book of Love (novel) - 1934

- Depression Island - 1935

- Co-op: a Novel of Living Together - 1936

- The Gnomobile - 1936, 1962

- Wally for Queen - 1936

- No Pasaran!: A Novel of the Battle of Madrid - 1937

- The Flivver King: A Story of Ford-America - 1937

- Little Steel - 1938

- Our Lady - 1938

- Expect No Peace - 1939

- Marie Antoinette (novel) - 1939

- Telling The World - 1939

- Your Million Dollars - 1939

- World's End - 1940

- World's End Impending - 1940

- Between Two Worlds - 1941

- Dragon's Teeth - 1942

- Wide Is the Gate - 1943

- Presidential Agent, 1944

- Dragon Harvest - 1945

- A World to Win - 1946

- A Presidential Mission - 1947

- A Giant's Strength - 1948

- Limbo on the Loose - 1948

- One Clear Call - 1948

- O Shepherd, Speak! - 1949

- Another Pamela - 1950

- Schenk Stefan! - 1951

- A Personal Jesus - 1952

- The Return of Lanny Budd - 1953

- The Cup of Fury - 1956

- What Didymus Did - UK 1954 / It Happened to Didymus - US 1958

- Theirs be the Guilt - 1959

- Affectionately Eve - 1961

- The Coal War - 1976

Autobiographical

- The Autobiography of Upton Sinclair. With Maeve Elizabeth Flynn III. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1962.

- My Lifetime in Letters. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1960.

Non-fiction

- Good Health and How We Won It: With an Account of New Hygiene (1909) - 1909

- The Fasting Cure - 1911

- The Profits of Religion - 1917

- The Brass Check - 1919

- The McNeal-Sinclair Debate on Socialism - 1921

- The Goose-Step - 1923

- Letters to Judd, an American Workingman - 1925

- Mental Radio: Does it work, and how? - 1930, 1962

- Upton Sinclair Presents William Fox - 1933

- We, People of America, and how we ended poverty : a true story of the future - 1933

- I, Governor of California - and How I Ended Poverty - 1933

- The Epic Plan for California - 1934

- I, Candidate for Governor - and How I Got Licked - 1935

- Epic Answers: How to End Poverty in California (1935) - 1934

- What God Means to Me - 1936

- Upton Sinclair on the Soviet Union - 1938[71]

- Letters to a Millionaire - 1939

Drama

- Plays of Protest: The Naturewoman, The Machine, The Second-Story Man, Prince Hagen - 1912

- The Pot Boiler - 1913

- Hell: A Verse Drama and Photoplay - 1924

- Singing Jailbirds: A Drama in Four Acts - 1924

- Bill Porter: A Drama of O. Henry in Prison - 1925

- The Enemy Had It Too: A Play in Three Acts - 1950

As editor

See also

- Upton Sinclair House — in Monrovia, California.

- Will H. Kindig, a supporter on the Los Angeles City Council

- J.P.Morgan

Notes

- ^ According to Craig, at her insistence Sinclair published Sylvia (1913) under his name. In her 1957 memoir, she described how she and her husband had collaborated on the work:

"Upton and I struggled through several chapters of Sylvia together, disagreeing about something on every page. But now and then each of us admitted that the other had improved something. I was learning fast now that this novelist was not much of a psychologist. He thought of characters in a book merely as vehicles for carrying his ideas."

References

- ^ The Jungle: Upton Sinclair's Roar Is Even Louder to Animal Advocates Today, Humane Society of the United States, March 10, 2006, archived from the original on January 6, 2010, retrieved June 10, 2010

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Upton Sinclair", Press in America, PB works.

- ^ a b "Uppie's Goddess", Books, Time, November 18, 1957, retrieved November 6, 2010.

- ^ Harris, Leon. (1975) “Upton Sinclair: American Rebel.” Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York.

- ^ Derrick, Scott (2002), "What a Beating Feels Like: Authorship Dissolution, and Masculinity in Sinclair's The Jungle", in Bloom, Harold (ed.), Upton Sinclair's The Jungle, Infobase, pp. 131–32.

- ^ a b c d e f Harris, Leon. (1975). "Upton Sinclair: American Rebel." Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York.

- ^ Sinclair, Upton, "Joslyn T Pine Note", in Negri, Paul (ed.), The Jungle, Dover Thrift, pp. vii–viii.

- ^ Harris, Leon. (1975) "Upton Sinclair: American Rebel." Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York.

- ^ Sinclair, Upton (1906). "What Life Means to Me". The Cosmopolitan. Schlicht & Field. pp. 591ff. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ a b Harris, Leon. (1975). "Upton Sinlclair: American Rebel." Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York.

- ^ "Upton Sinclair", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Yoder, Jon A. (1975) "Upton Sinclair." Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., New York.

- ^ Yoder, Jon. (1975). "Upton Sinclair." Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., New York.

- ^ a b Harris, Leon. (1975.) "Upton Sinclair: American Rebel." Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York.

- ^ "How Upton Sinclair Turned The Jungle Into a Failed New Jersey Utopia".

- ^ "Upton Sinclair's Colony To Live At Helicon Hall. Luxury In Co-Operation And There May Be Some Compromises Just At First" (PDF). The New York Times. 7 October 1906. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Paulin, LRE (March 1907). "Simplified Housekeeping: The Present Quarters of Upton Sinclair's Colony At Englewood, New Jersey". Indoors and Out: the Homebuilder's Magazine. III (6): 288–92. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ^ "Fire Wipes Out Helicon Hall, And Upton Sinclair Hints That the Steel Trust's Hand May Be In It" (PDF). The New York Times. 17 March 1907. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Harry W. Laidler, "Ten Years of ISS Progress," The Intercollegiate Socialist, vol. 4, no. 1 (Oct.-Nov. 1915), pg. 16.

- ^ Graham, John (1976). The Coal War. Boulder, CO: Colorado Associated University Press. pp. lvi–lxxv. ISBN 0-87081-067-7.

- ^ Dashiell, Chris (1998), "Eisenstein's Mexican Dream", Cinescene, retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (1957), Fads & Fallacies in the Name of Science, Courier Dover, pp. 309–10

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help), Google Books. - ^ Mental Radio (Books), Google, retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ^ The Next Los Angeles: The Struggle for a Livable City (second ed.). Berkeley, California: University of California Press. 2005. ISBN 978-0-520-25009-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Katrina Vanden Heuvel, The Nation 1865-1990, p. 80, Thunder's Mouth Press, 1990 ISBN 1-56025-001-1

- ^ Sinclair, Upton. "End Poverty in California The EPIC Movement", The Literary Digest, 13 Oct 1934

- ^ Bread Upon The Waters, ch. 31, by Rose Pesotta, 1945

- ^ Rob Leicester Wagner, Hollywood Bohemia: The Roots of Progressive Politics in Rob Wagner's Script (Janaway Publishing, 2016) (ISBN 978-1-59641-369-6)

- ^ Alden Whitman, Rebel With a Cause, New York Times, November 26, 1968

- ^ James N. Gregory, "Upton Sinclair's 1934 EPIC Campaign: Anatomy of a Political Movement." Labor 12#4 (2015): 51-81.

- ^ Greg Mitchell, The Campaign of the Century: Upton Sinclair and the EPIC Campaign in California (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1991)

- ^ Patterson, William H. Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue with His Century: Volume 1 (1907-1948): Learning Curve New York: Tor Books, 2010; pp. 187-205, 527-530, and passim

- ^ Rossiter, Caleb S. The Turkey and the Eagle: The Struggle for America's Global Role. p. 207.

- ^ Spartacus Educational: "Socialist Party of America," Upton Sinclair, letter to Norman Thomas (25th September, 1951), accessed June 10, 2010

- ^ Arthur 2006.

- ^ Arthur 2006, pp. 132–33.

- ^ "Mrs. Upton Sinclair, Author's Wife, Dies". The Bridgeport Post. Bridgeport, Connecticut. 20 Dec 1967. p. 72. Retrieved 17 May 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Arthur 2006, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Arthur 2006, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Arthur 2006, p. 109.

- ^ Arthur 2006, pp. 111–12.

- ^ Upton Sinclair, Mammonart, p. 270

- ^ "Upton Sinclair, Author, Dead", The New York Times, November 26, 1968, retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ "The Jungle", History News Network

- ^ Sinclair, Upton. The Jungle, Dover Thrift Editions, General Editor Paul Negri; Editor of The Jungle, Joslyn T Pine. Note: pp. vii-viii

- ^ Socalhistory.org

- ^ "Sinclair's 'The Jungle' Turns 100", PBS Newshour, 10 May 2006, accessed 10 June 2010

- ^ Marcus, p. 131

- ^ Bloom, Harold. Ed., 'Upton Sinclair's The Jungle,' Infobase Publishing, 2002, p. 11

- ^ Fulton Oursler, Behold This Dreamer! (Boston: Little, Brown, 1964), p. 417

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore (1951–54), "July 31, 1906", in Morison, Elting E (ed.), The Letters, vol. 5, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, p. 340.

- ^ "Upton Sinclair, The Jungle", Spartacus, UK: School net.

- ^ "Upton Sinclair & The Jungle", Socialist standard, no. 1227, World socialism, Nov 2006.

- ^ Sinclair, Mary Craig, Southern Belle, pp. 106–8, 111–2, 129–32, 142, quote 111–2.

- ^ Prenshaw, Peggy W, "Sinclair, Mary Craig Kimbrough", in Lloyd, James B (ed.), Lives of Mississippi Authors, 1817–1967 (Google Books), pp. 409–10, retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "'Sylvia': Mr. Upton Sinclair's Novel upon a Much-Discussed Theme", The New York Times, 25 May 1913, retrieved November 6, 2010

- ^ Southern Belle, p. 146.

- ^ Upton Sinclair, The Autobiography of Upton Sinclair, NY: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1962, pp. 180, 195

- ^ Lepore, Jill. "The Lie Factory." The New Yorker.

- ^ Salamon, Julie (22 July 2005). "Upton Sinclair: Revisit to Old Hero Finds He's Still Lively". New York Times. Books. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ Brennan, Elizabeth A.; Clarage, Elizabeth C. (1999). Who's Who of Pulitzer Prize Winners. Phoenix: Oryx Press. p. 493. ISBN 978-1-57356-111-2. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Openroadmedia.com

- ^ "'The Fasting Cure', by Upton Sinclair", Soil and Health

- ^ "Perfect Health!" (chapter), The Fasting Cure, at Soil and Health

- ^ "The Use of Meat" (chapter). The Fasting Cure, at Soil and Health

- ^ L'Official, Peter. "Left Behind". The Village Voice (14 February 2006). Villagevoice.com. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ "The Jungle". silentera.com.

- ^ "The Jungle (1914)", The New York Times, retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "The Gnome-Mobile", Internet Movie Database, retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ "There Will Be Blood", Internet Movie Database, 2007.

- ^ New York : Weekly Masses Co.

Further reading

- Arthur, Anthony (2006), Radical Innocent Upton Sinclair, New York: Random House.

- William A. Bloodworth, Jr., Upton Sinclair. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1977.

- Lauren Coodley, editor, The Land of Orange Groves and Jails: Upton Sinclair's California. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 2004.

- Lauren Coodley, Upton Sinclair: California Socialist, Celebrity Intellectual. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2013.

- Engs, Ruth Clifford, [Ed] Unseen Upton Sinclair: Nine Unpublished Stories, Essays and Other Works. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. 2009.

- Graham, John, The Coal War, Colorado Associated University Press, 1976.

- Ronald Gottesman, Upton Sinclair: An Annotated Checklist. Kent State University Press, 1973.

- Harris, Leon. Upton Sinclair, American Rebel. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co, 1975.

- Leader, Leonard. "Upton Sinclair's EPIC Switch: A Dilemma for American Socialists." Southern California Quarterly 62.4 (1980): 361-385.

- Mattson, Kevin. Upton Sinclair and the Other American Century. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2006.

- Mitchell, Greg. The Campaign of the Century: Upton Sinclair and the EPIC Campaign in California. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1991.

- Swint, Kerwin. Mudslingers: The Twenty-five Dirtiest Political Campaigns of All Time. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2006.

- Jon A. Yoder, Upton Sinclair. New York: Frederick Ungar, 1975.

- Martin Zanger, "Upton Sinclair as California's Socialist Candidate for Congress, 1920," Southern California Quarterly, vol. 56, no. 4 (Winter 1974), pp. 359–73.

External links

- Works by Upton Sinclair at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Upton Sinclair at Internet Archive

- Works by Upton Sinclair at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Jungle Department of American Studies, University of Virginia

- The Cry for Justice: An Anthology of the Literature of Social Protest, Bartleby.com

- Guide to the Upton Sinclair Collection, Lilly Library, Indiana University

- Phelps, Christopher (26 June 2006), The Fictitious Suppression of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, History News network.

- Upton Sinclair, "EPIC", Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

- "A Tribute To Two Sinclairs", Sinclair Lewis & Upton Sinclair

- Information about Sinclair and Progressive Journalism today

- "Writings of Upton Sinclair" from C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History

- Upton Sinclair at Find a Grave

- "Upton Sinclair's 1929 letter to John Beardsley", Upton Sinclair to John Beardsley

- Upton Sinclair - Induction into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame

- 1878 births

- 1968 deaths

- Writers from California

- Writers from New York

- American investigative journalists

- 19th-century American novelists

- American male novelists

- Pulitzer Prize for the Novel winners

- 20th-century American novelists

- American activists

- American socialists

- American progressives

- California Democrats

- American temperance activists

- Mustin family

- City College of New York alumni

- Columbia University alumni

- Socialist Party of America politicians from California

- Writers from Baltimore

- People from Englewood, New Jersey

- People from the San Gabriel Valley

- Progressive Era in the United States

- People associated with the Dil Pickle Club

- Burials at Rock Creek Cemetery

- Self-published authors

- War Resisters League activists

- Criticism of Christianity

- 20th-century American writers

- 19th-century male writers