Medieval cuisine: Difference between revisions

revert for the time being: ravaging the existing article structure is not an improvement |

→Beer and ale: drinking olive oil? |

||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

===Beer and ale=== |

===Beer and ale=== |

||

While wine was the most common [[table beverage]] in much of Europe, this was not the case in the northern regions where grapes were not cultivated. Those who could afford it purchased imported wine, but even among royalty and nobility in these areas, it was common to drink [[beer]] or [[ale]], particularly towards the end of the Middle Ages. In England, the [[Lowlands]], northern [[Germany]] and [[Scandinavia]] beer was consumed on a daily basis by most of the population. However, the heavy influence from Arab and Mediterranean culture on medical science (particularly due to the [[Reconquista]] and the influx of Arabic texts) meant that beer was often heavily disfavored. For most medieval Europeans, it was a humble brew compared with common southernly drinks and cooking ingredients, such as wine or olive oil. Even comparatively exotic products like [[camel]]'s milk and [[gazelle]] meat could receive more positive attention in many medical treatises. Beer was usually no more than an acceptable alternative and was assigned various negative qualities. In 1256, the [[Siena|Sienese]] physician [[Aldobrandino]] described beer in the following way: |

While wine was the most common [[table beverage]] in much of Europe, this was not the case in the northern regions where grapes were not cultivated. Those who could afford it purchased imported wine, but even among royalty and nobility in these areas, it was common to drink [[beer]] or [[ale]], particularly towards the end of the Middle Ages. In England, the [[Lowlands]], northern [[Germany]] and [[Scandinavia]] beer was consumed on a daily basis by most of the population. However, the heavy influence from Arab and Mediterranean culture on medical science (particularly due to the [[Reconquista]] and the influx of Arabic texts) meant that beer was often heavily disfavored. For most medieval Europeans, it was a humble brew compared with common southernly drinks and cooking ingredients, such as wine or olive oil{{fact}}. Even comparatively exotic products like [[camel]]'s milk and [[gazelle]] meat could receive more positive attention in many medical treatises. Beer was usually no more than an acceptable alternative and was assigned various negative qualities. In 1256, the [[Siena|Sienese]] physician [[Aldobrandino]] described beer in the following way: |

||

{{cquote|But from whichever it is made, whether from oats, barley or wheat, it harms the head and the stomach, it causes bad breath and ruins the teeth, it fills the stomach with bad fumes, and as a result anyone who drinks it along with wine becomes drunk quickly; but it does have the property of facilitating urination and makes one's flesh white and smooth.}} |

{{cquote|But from whichever it is made, whether from oats, barley or wheat, it harms the head and the stomach, it causes bad breath and ruins the teeth, it fills the stomach with bad fumes, and as a result anyone who drinks it along with wine becomes drunk quickly; but it does have the property of facilitating urination and makes one's flesh white and smooth.}} |

||

The intoxication induced by beer was believed to last longer than that of wine, but it was also, almost grudgingly, admitted that it did not create the "false thirst" associated with wine. Though less prominent than in the north, beer was known and consumed in northern France and the Italian mainland. Perhaps as a consequence of the Norman conquest and the movement of nobles from France to England and back, one French variant described in the 14th century [[cookbook]] ''[[Le Menagier de Paris]]'' called ''godale'' (most likely a direct borrowing from the English "good ale") was made from barley and [[spelt]], but without [[hops]]. In England there were also the variants ''[[posset|poset ale]]'', made from hot milk and cold ale, and ''brakot'' or ''braggot'', a spiced ale prepared much like [[hypocras]].<ref>Scully pg. 151-154</ref> |

The intoxication induced by beer was believed to last longer than that of wine, but it was also, almost grudgingly, admitted that it did not create the "false thirst" associated with wine. Though less prominent than in the north, beer was known and consumed in northern France and the Italian mainland. Perhaps as a consequence of the Norman conquest and the movement of nobles from France to England and back, one French variant described in the 14th century [[cookbook]] ''[[Le Menagier de Paris]]'' called ''godale'' (most likely a direct borrowing from the English "good ale") was made from barley and [[spelt]], but without [[hops]]. In England there were also the variants ''[[posset|poset ale]]'', made from hot milk and cold ale, and ''brakot'' or ''braggot'', a spiced ale prepared much like [[hypocras]].<ref>Scully pg. 151-154</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:02, 20 March 2007

Medieval cuisine refers to the variety of foods eaten by the various European cultures during the Middle Ages. During this period, diets and cooking changed across Europe, and many of these changes laid the foundations for contemporary regional and folk cuisines. Transportation and communication was slow and prevented the export of many foods, especially fresh fruit and meat, which today are commonplace in all industrialized nations, and imported ingredients were the preserve of the wealthy. Thus the foods eaten by the wealthy nobility were considerably more prone to foreign influence than the foods of lower strata of society, as nobles and the upper gentry sought to emulate the royal table. As each level of society imitated the one above it, innovations from international trade and foreign wars were gradually disseminated through the upper middle class of medieval towns.

In a time when famines were commonplace and social hierarchies often enforced with considerable brutality, food was an important marker of social status in a way that has no equivalent today. Other than economic unavailability of luxuries like imported spices, there were decrees that outlawed the consumption of certain foods for individuals of certain social classes and sumptuary laws were used to limit the conspicuous consumption of the nouveau riche who were not nobility. Social norms also dictated that the food of the working class should be less refined, since it was believed that there was a divine or natural resemblance between one's labor and one's food, so manual labor required coarser, cheaper food. Contemporary medicine similarly recommended expensive tonics, theriacs, and exotic spices to cure the maladies of the nobility, while recommending the more odorous and lower-ranked garlic to the common man.

The single most important foodstuff was bread, and to a lesser extent other foods made from cereals such as porridge and pasta. Meat, as today, was more prestigious but more expensive and therefore less cost-efficient than grain or vegetables. Common ingredients used in cooking were verjuice, wine and vinegar. These, combined with the widespread usage of sugar (among those who could afford it), gave many dishes a distinctly sweet-sour flavor. The most popular types of meat were pork and chicken, while beef required greater investment in land and grazing and therefore was less common. Cod and herring formed the mainstay for a large proportion of the northern populations, but a wide variety of both saltwater and freshwater fish was also eaten. Almonds, both sweet and bitter, were eaten whole as garnish, or more commonly ground up and used as a thickener in soups, stews, and sauces. Particularly popular was almond milk, which was a common substitute for animal milk during Lent and fasts.

Meals

There were typically two meals a day in medieval society: dinner (the medieval equivalent of the modern lunch) around noon and a lighter supper later at night. Moralists of the day frowned on breaking the overnight fast too early in the day, and members of the church and the cultivated gentry avoided it. For practical reasons breakfast was still eaten by a large proportion of working men and having an early morning meal was tolerated for young children, women, the elderly and the sick. Because the medieval church preached against gluttony at least as often as other weaknesses of the flesh, men tended to be ashamed of breakfast and would not admit to succumbing to this weak practicality. Lavish dinner banquets and late night reresopers with considerable amounts of alcohol were considered immoral. The latter especially was associated with vices like gambling, crude language, drinking, and lewd flirtation. Minor meals and snacks were common (though also disliked by the church), and working men commonly received an allowance from their employers in order to purchase nuncheons, small morsels to be eaten during breaks.

There was an increasing trend throughout the Middle Ages to escape the stern collectivism that permeated the entire period to allow for a minimum of privacy. Nevertheless, the medieval meal was, like just about every part of life, considered a communal affair. The entire household, wife and husband, parents and children, master and servant, should ideally dine together. To furtively sneak off to enjoy the private company of a friend or two was considered inefficient; a haughty display of egotism in a world where every member of society depended on the goodwill of one's fellow man. In the 13th century, English bishop Robert Grosseteste gave the following advice to the Countess of Lincoln: "forbid dinners and suppers out of hall, in secret and in private rooms, for from this arises waste and no honour to the lord and lady." He followed this lecture with a reminder to keep an eye on the servants in order that they would not make off with the leftovers to make merry at reresopers, rather than giving it as alms to the poor. Regretfully absent from most sources is any great detail about the everyday meals of the elite, or just about any details about the eating habits of the common people or the destitute. Mealtimes were similar, but little or nothing is known of table manners, except that they did not generally involve such extravagant luxuries as multiple courses, luxurious spices or handwashing in scented water.[1]

Before the meal and after each course shallow basins filled with water and linen towels were offered to guests so they could wash their hands, and great emphasis was put on cleanliness. Overall, banqueting and fine dining was a predominantly male affair. It was uncommon for anyone but the most honored of guests to bring his wife or her ladies-in-waiting. Since social codes made it difficult for women to uphold the stereotype of being neat, delicate and immaculate while enjoying a sumptuous feast, the wife of the host often dined in private with her entourage. She could then join dinner only after the potentially messy and practical business of eating was finished. The collective and hierarchical nature of medieval society was reinforced in rules of etiquette where the lower ranked were expected to help those in a higher position, the younger to assist the older, and men to spare women the risk of sullying dress and reputation by having to handle the food in an unwomanly fashion. Shared drinking cups were common even at lavish banquets for all but those who sat at the high table, as was the standard etiquette of breaking bread and carving meat for one's fellow diners.[2]

Food was mostly served on plates or in stewpots, and diners would help themselves by taking their share from the shared dishes and place it on trenchers of stale bread, wood or pewter with the help of spoons or bare hands. In lower class households it was common to eat food straight off the table. Knives were used at the table, but most people were expected to bring their own, and only highly favored guests would be given a personal knife. A knife was usually shared with at least one other dinner guest unless one was of very high rank or well-acquainted with the host. Forks for eating were not in widespread usage in Europe until the Modern era and early on were limited to Italy, most likely because the most common staple food was pasta. Still, it was not until the 14th century that the fork became common among Italians of all social classes. The change in attitudes can be illustrated by the reactions to the table manners of the Byzantine princess Theodora Doukaina in the 11th century. She was the future wife of the Doge of Venice, Domenico Selvo, and caused considerable dismay among upstanding Venetians. The foreign consort's insistence on having her food cut up by her eunuch servants and then eating the pieces with a golden fork shocked and upset the diners so much that the Bishop of Ostia later interpreted her refined foreign manners as pride and later referred to her as "...the Venetian Doge's wife, whose body, after her excessive delicacy, entirely rotted away."[3]

Food preparation

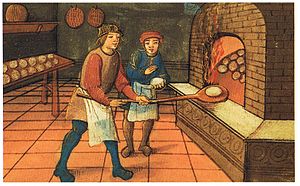

All types of medieval cooking were in one way or another done with fire. Stoves, let alone electric ones, didn't appear until the 18th century, and any cook had to have a minimum of knowledge of how to regulate cooking utensils directly over an open fire. Ovens were used, but they were expensive to construct and were something that only existed in fairly large households and bakeries. It was common for a community to have shared ownership of an oven to ensure that the bread baking essential to everyone was made a communal concern, rather than a private one. There were also portable ovens designed to be filled with food and then buried in hot coals, and even larger ones on wheels that were used to sell pies in the streets of medieval towns. But for most people almost all cooking was done in simple stewpots, since this was the most efficient use of firewood and did not waste precious cooking juices, making potages and stews the most most common dishes.[4]

One of the things that sets medieval cuisine apart from modern cooking norms was less (or at least different kind of) prejudices against what type of foods that could be combined. Fruit was readily and without hesitation combined with meat, fish and eggs. The recipe for Tart de brymlent, a fish pie from the recipe collection Forme of Cury includes a mix of figs, raisins, apples and pears with fish (salmon, codling or haddock) and pitted damson plums under the top crust.[5] It was more important to make sure that the dish agreed with contemporary standards of medicine and dietetics. This meant that food had to be "tempered" according to its nature by an appropriate combination of preparation and mixing certain ingredients, condiments and spices. For example, fish was considered to be quite cold and moist and should preferably be cooked in a way that heated and dried it, such as frying or oven baking, and seasoned with hot and dry spices; beef was dry and hot and should therefore be boiled; pork was hot and moist and should therefore always be roasted.[6] In some recipe collections, alternative ingredients were assigned with more consideration to the humoral nature than similarity in taste. In a recipe for quince pie, cabbage is given as working equally well, and in other turnips is considered the be equivalent of pears.[7]

Preservation

Methods of preserving food during the Middle Ages were basically the same methods that had been used since antiquity, and didn't change significantly until the invention of canning in the early 19th century. The most common and simplest method was to expose foodstuffs to heat or wind to remove moisture and thereby significantly prolonging the durability, though not the flavor, of almost any type of food from cereals to meats; the drying of food worked by killing or drastically reducing the activity of various microorganisms that cause decay. In warm climates this was mostly achieved by leaving food out to dry in the sun, and in the cooler northern climates by exposure to strong winds (especially common for the preparation of stockfish), in warm ovens, and cellars, attics and at times even in living quarters.

Subjecting food to a number of chemical processes such as cooking, salting, brining, conserving or fermenting also made it keep longer. Most of these methods had the advantage of shorter preparation times and of introducing new flavors. Smoking or salting meat of livestock butchered in the fall was a common household strategy to avoid the need of having to feed more animals than necessary during the lean winter months. Butter tended to be heavily salted (5-10%) in order not to spoil. Vegetables, eggs or fish were also often pickled in tightly packed jars, containing brine and acidic liquids (lemon juice, verjuice or vinegar). Another method was to create a seal around the food by cooking it in sugar or honey, or in fat, in which it was then stored. Other than slowing or halting the process of putrefaction, it was also encouraged through a number of methods; grains, fruit and grapes were turned into alcoholic drinks that disinfected the beverage, and milk was fermented and cured into a multitude of cheeses or buttermilk.[8]

Cereals

The phrase Our daily bread is largely figurative to most Europeans today, but was a concrete reality during the Middle Ages. Food intake among all social classes consisted mainly of cereals, usually in the form of bread and, to a lesser extent, gruel, porridge, and pasta. Estimates of bread consumption all over Europe have turned out to be fairly similar: around 1–1.5 kg (2–3 lb) of bread per person per day. The most common grains were rye, barley, buckwheat, millet and oats. Rice remained a fairly expensive import for most of the Middle Ages and was grown in northern Italy only towards the end of the period. Wheat was common all over Europe and was considered to be the most nutritious of all grains, but was far more expensive since it carried with it a higher social prestige. The finely sifted white flour that modern Europeans are most familiar with was reserved for the bread of the upper classes, while those of lower status ate bread that became coarser, darker and of a higher bran content the lower one was on the social ladder. In times of grain shortages or outright famine, grains could be supplemented with cheaper and less desirable substitutes like chestnuts, dried legumes, acorns, ferns and a wide variety of more or less nutritious vegetable matter.

One of the most common constituents of a medieval meal, either as part of a banquet or as a small snack, were sops, pieces of bread with which a liquid like wine, soup, broth, or sauce could be soaked up and eaten. Another common sight at the medieval dinner table was the frumenty, a thick wheat porridge often boiled in a meat broth and seasoned with spices. Porridges were also made of every type of grain and could be served as desserts or dishes for the sick if boiled in milk (or almond milk) and sweetened with sugar. Pies[9] filled with meats, eggs, vegetables or fruit were common throughout Europe as were turnovers, fritters, donuts and many similar pastries. By the Late Middle Ages biscuits, and especially wafers, eaten for dessert had become high-prestige foods and came in many varieties. Grain, either as bread crumbs or flour, was also the most common thickener of soups and stews along, or in combination, with almond milk.

The importance of bread as a daily staple meant that bakers played a crucial role in any medieval community. Among the first town guilds to be organized were the bakers', and laws and regulations were passed to keep bread prices stable. The English Assize of Bread and Ale of 1266 listed extensive tables where the size, weight, and price of a loaf of bread was regulated in relation to grain prices. The baker's profit margin stipulated in the tables was later increased through successful lobbying from the London Baker's Company by adding the cost of everything from firewood and salt to the baker's wife, house and dog. Since bread was such a central part of the medieval diet, swindling by those who were trusted with supplying the precious commodity to the community was considered a serious offense. Bakers who were caught tampering with weights or diluting their doughs with less expensive ingredients could receive severe penalties.[10]

Bread was put to use for more than just eating: though often of wood or metal (mostly pewter), trenchers that served as dinner plates in affluent households were made out of old bread made from unsifted flour far into the early modern era, and bread was used to wipe off knives when passing them to the next diner or before fishing out salt from the shared salt cellars. Even the seemingly carefree handling of hot metal serving plates could be achieved with slices of bread neatly tucked into the hands of servants, but still away from the unforgiving gaze of fussy, high-ranking diners.[11]

Fruit and vegetables

While grains were the primary constituent of almost every meal, various vegetables such as cabbage, beets, onions, garlic and carrots were also common foodstuffs. Many of these plants were eaten on a daily basis by peasants and workers, but were less prestigious than meat. The cookbooks, intended mostly for those who could afford such luxuries, that appeared in the late Middle Ages only contain a small percentage of recipes using vegetables other than side dishes and the occasional potage. Carrots had been known in Europe since prehistoric times, and existed in two variants during the Middle Ages: a tastier redish-purple variety and a less prestigous green-yellow type. The orange carrot that is the most common today did not appear until the 17th century. Various legumes, like chickpeas, fava beans and peas were also common and important sources of protein. With the exception of peas, they were generally frowned on by contemporary dietetics, partly because of their tendency to cause flatulence. The importance of vegetables to the common people is exemplified by accounts from 16th century Germany stating that many peasants ate sauerkraut three to four times a day.[12]

Fruit was popular and could be served fresh, dried, or preserved, and was a common ingredient in many meat dishes. The practice of eating raw fruit was disfavored by physicians because of the belief that they were generally too cold or moist to be eaten uncooked. Since sugar and honey were expensive, it was common to include many types of fruit in dishes that called for sweeteners of some sort. The fruits of choice in the south were lemons, citrons, bitter oranges (the sweet type was not introduced until several hundred years later), pomegranates, quinces, and, of course, grapes. Further north apples, pears, plums, and strawberries were more common. Figs and dates were eaten all over Europe, but remained rather expensive imports in the north.

Common and often basic ingredients in many modern European cuisines like potatoes, kidney beans, cacao, tomatoes, chili peppers and maize were not available to Europeans until the late 15th century with the discovery of the Americas, and even then it often took a long time for the new foodstuffs to be accepted by society at large.[13]

Meats

While all forms of wild game were popular among those who could obtain it, most meat came from domesticated animals. Beef was not as common as today because raising cattle was labor-intensive, requiring pastures and feed, and oxen and cows were much more valuable as draught animals and for producing milk. The flesh of animals that were slaughtered because they were no longer able to serve was not particularly appetizing and therefore less valued. Far more common was pork, as pigs required less attention and cheaper feed. Domestic pigs often ran freely even in towns and could be fed on just about any organic kitchen waste, and suckling pig was a sought-after delicacy. Mutton and lamb was fairly common, especially in areas with a sizeable wool industry, as was veal. Unlike many parts of the modern Western world just about every part of the animal was eaten, including ears, snout, tail, tongue, and womb. Intestines, bladder and stomach could be used as casings for sausage or even illusion food such as giant eggs. Among the meats that today are rare or even considered inappropriate for human consumption were hedgehog and porcupine, occasionally mentioned in late medieval recipe collections.[14]

A wide range of birds were eaten, including swans, peafowl, quail, partridge, storks, cranes, larks and just about any wild bird that could be hunted successfully. Swans and peafowl were often domesticated, but were only eaten by the social elite and were more praised for their fine appearance (often used to create stunning subtleties) than their meat. As today, geese and ducks had been domesticated but were not as popular as the chicken, the fowl equivalent of the pig. Interestingly enough, barnacle geese were by legend considered to reproduce not by laying eggs like other birds, but by growing in barnacles and were hence considered acceptable food for fast and Lent.[13]

Meats were more expensive than grain and vegetables throughout the entire Middle Ages. Though rich in protein, the calorie-to-weight ratio of meat was always less than that of any vegetable food. Meat could be up to four times as expensive as bread. Fish was up to 16 times as costly, and was still fairly expensive even for coastal populations. This meant that fasts could mean an especially meager diet for those who could not afford alternatives to meat and animal products like milk and eggs. It was only after the demographic catastrophe of the Black Death had eradicated up to half of the European population that meat became more common even for the poorer segments. The drastic reduction in many over-populated areas resulted in a labor shortage, meaning that wages shot up. It also left vast areas of farmland without anyone to tend them, making them available for pasture and putting more meat on the market.[15]

Fish and seafood

Although ranked lower in prestige than other animal meats, and often seen as merely an alternative to meat on fast days, seafood was still the mainstay of many coastal populations. "Fish" to the medieval man was also a general category under which anything that wasn't considered a proper land-living animal was sorted, including marine mammals such as whales and porpoises. And through rather original reasoning the tails of beavers, due to the scaly nature and the considerable time it spent in water, and barnacle geese, due to the lack of knowledge of where they migrated, were also sorted into this category and deemed appropriate food for fast days.[16] Especially important was the fishing and trade in herring and cod in the Atlantic and the Baltic Sea. The herring was of unprecedented significance to the economy of much of Northern Europe, and it was one of the most common commodities traded by the Hanseatic League, a powerful north German allience of trading guilds. Kippers made from herring caught in the North Sea could be found in markets as far away as Constantinople. While large quantities of fish were eaten fresh, a large proportion was salted, dried, and, to a lesser extent, smoked. Stockfish, cod that was split down the middle, fixed to pole and dried, was very common, though preparation could be time consuming, and meant beating the dried fish with a mallet and soaking it in water. A wide range of mollusks including oysters, mussels and scallops were eaten by coastal and river dwelling populations, and freshwater crayfish were generally seen as a desirable alternative to meat during fish days. Compared to meat, fish was much more expensive for the inland population, especially in Central Europe, and therefore not an option for most. Fresh water fish such as pike, carp, bream, perch, lamprey, and trout were common.[13]

Drink

Water is often seen today as a common and neutral choice to drink with a meal. In the Middle Ages concerns over purity, medical recommendations and its low prestige value made it a less favorable option and alcoholic beverages were always preferred. They were considered to be more nutritious and beneficial to digestion than water with the invaluable bonus of being less prone to putrefaction due to the alcohol content. Wine was consumed on a daily basis in most of France and all over the Western Mediterranean wherever grapes were cultivated. Further north it remained the preferred drink of the bourgeoisie and the nobility who could afford it, and far less common among peasants and workers. The drink of commoners in the northern parts of the continent was primarily beer or ale; due to problems with preservation of this beverage for any long period (especially before the introduction of hops) it was mostly consumed fresh; it was therefore cloudier and perhaps of a lower alcohol content than the typical modern equivalent. Plain milk was not consumed by adults except the poor or sick, being reserved for the very young or elderly, and then usually as buttermilk or whey. Fresh milk was overall less common than other dairy products because of the lack of technology to keep it from spoiling.[17]

Juices, as well as wines, of a multitude of fruits and berries had been known at least since Roman antiquity and were still consumed in the Middle Ages; perry, cotignac from medlars or quince, wine from pomegranate, mulberries, blackberries and cider, which was especially popular in the north where both apples and pears were plentiful. Medieval drinks that have survived to this day include prunellé from wild plums (modern-day slivovitz), mulberry gin and blackberry wine. Many variants of mead have been found in medieval recipes, with or without alcoholic content. However, the honey-based drink became less common as a table beverage towards the end of the period and eventually wound up primarily as a sick-potion. Kumis, the fermented milk of mares or camels, was known in Europe but as with mead, was mostly something prescribed by physicians.[18]

Wine

Wine had the highest social prestige of all drinks and was also regarded as the healthiest choice. According to the dietetics based on Galenic theory it was considered to be hot and dry (hence the modern use of "dry" in describing the flavor of wine), but these qualities were moderated when wine was mixed with water before drinking, as it frequently was. Unlike water or beer, which were considered cold and moist, consumption of wine in moderation (especially red wine) was, among other things, believed to aid digestion, generate good blood and brighten the mood. The quality of wine differed considerably according to vintage, the type of grape and more importantly, on the number of grape pressings. The first pressing was made into the finest and most expensive wines which were reserved for the upper classes. The second and third pressings were subsequently of lower quality and alcohol content. Common folk usually had to settle for a cheap white or rosé from a second or even third pressing, meaning that it could be consumed in quite generous amounts without leading to heavy intoxication. For the poorest (or hard-line religious ascetics), watered-down vinegar would often be the only available choice.

The aging of high quality red wines required more specialized knowledge as well as expensive storage and equipment, and resulted in an even more expensive end product. Judging from the advice given in many medieval documents on how to salvage wine that bore signs of going bad, preservation must have been a widespread problem. Even if vinegar was a common ingredient in many dishes, there was only so much of it that could be used at one time. In the 14th century cookbook Le Viandier there are several methods for salvaging spoiling wine; making sure that the wine barrels are always topped up or adding a mixture of dried and boiled white grapeseeds with the ash of dried and burnt lees of white wine were both effective bactericides, even if the chemical processes were not understood at the time. Spiced or mulled wine was not only popular among the affluent, but also considered especially healthy by physicians. Wine was believed to act as a kind of vaporizer and conduit of other foodstuffs to every part of the body, and the addition of fragrant and exotic spices would make it even more wholesome. Spiced wines were usually made by mixing an ordinary (red) wine with an assortment of spices such as ginger, cardamom, pepper, grains of paradise, nutmeg, cloves and sugar. These would be contained in small bags which were either steeped in wine or had liquid poured over them to produce hypocras and claré, and by the 14th century bagged spice mixes could be bought ready-made from spice merchants.[19]

Beer and ale

While wine was the most common table beverage in much of Europe, this was not the case in the northern regions where grapes were not cultivated. Those who could afford it purchased imported wine, but even among royalty and nobility in these areas, it was common to drink beer or ale, particularly towards the end of the Middle Ages. In England, the Lowlands, northern Germany and Scandinavia beer was consumed on a daily basis by most of the population. However, the heavy influence from Arab and Mediterranean culture on medical science (particularly due to the Reconquista and the influx of Arabic texts) meant that beer was often heavily disfavored. For most medieval Europeans, it was a humble brew compared with common southernly drinks and cooking ingredients, such as wine or olive oil[citation needed]. Even comparatively exotic products like camel's milk and gazelle meat could receive more positive attention in many medical treatises. Beer was usually no more than an acceptable alternative and was assigned various negative qualities. In 1256, the Sienese physician Aldobrandino described beer in the following way:

But from whichever it is made, whether from oats, barley or wheat, it harms the head and the stomach, it causes bad breath and ruins the teeth, it fills the stomach with bad fumes, and as a result anyone who drinks it along with wine becomes drunk quickly; but it does have the property of facilitating urination and makes one's flesh white and smooth.

The intoxication induced by beer was believed to last longer than that of wine, but it was also, almost grudgingly, admitted that it did not create the "false thirst" associated with wine. Though less prominent than in the north, beer was known and consumed in northern France and the Italian mainland. Perhaps as a consequence of the Norman conquest and the movement of nobles from France to England and back, one French variant described in the 14th century cookbook Le Menagier de Paris called godale (most likely a direct borrowing from the English "good ale") was made from barley and spelt, but without hops. In England there were also the variants poset ale, made from hot milk and cold ale, and brakot or braggot, a spiced ale prepared much like hypocras.[20]

That hops could be used for flavoring beer had been known at least since Carolingian times, but was adopted only gradually due to the difficulties in establishing the appropriate proportions. Before the discovery of hops as a beer flavorer, gruit, a mix of various herbs, had been used for this purpose. Gruit did not have the same conserving properties as hops and the end result usually had to be consumed rather quickly, since it spoiled in relatively short time. Another method of flavoring beer was to increase the alcohol content, but this was more expensive and lent the beer the undesired characteristic of being a quick and heavy intoxicant when imbibed. In the Early Middle Ages beer was primarily brewed in monasteries, and on a smaller scale in individual households. By the High Middle Ages breweries in the fledgling medieval towns of northern Germany began to take over the production. Though most of the breweries were small family businesses that employed at most eight to ten people, the regular production allowed for investments in better equipment and increased experimentation with new recipes and brewing techniques. These types of operations later spread to Holland in the 14th century, then to Flanders and Brabant and reached England by the 15th century. Hopped beer became very popular in the last decades of the Late Middle Ages. In England and the Low Countries, the per capita consumption lay around 275-300 liters (60-66 gallons) a year and was consumed with practically every meal: low alcohol-content beers for breakfast and stronger ones later in the day. When perfected as an ingredient, hops could make beer keep for six months or more, and facilitated extensive exports.[21]

Distillates

The art of distillation was practiced by the Chinese, who prepared a form of rice whiskey in porcelain stills as early as the 9th century BC. The ancient Greeks and Romans also knew of the technique, but it was not practiced on a major scale until some time around the 12th century, when Arabic innovations in the field combined with water-cooled glass alembics were introduced. Distillation was believed by medieval scholars to produce the essence of the liquid being purified, and the term aqua vitae ("water of life") was used as a generic term for all kinds of distillates into the 17th century. The early use of various distillates, alcoholic or not, was varied, but it was primarily culinary or medicinal; grape syrup mixed with sugar and spices was prescribed for a variety of ailments and rose water was used as a perfume, a cooking ingredient and for hand washing. Alcoholic distillates were also occasionally used to create dazzling, fire-breathing subtleties (a type of entertainment dish served between courses) by soaking a piece of cotton in spirits. It would then be placed in the mouth of the stuffed, cooked and occasionally redressed animals, and lit just before presenting the creation.

Aqua vitae in its alcoholic forms was highly praised by medieval physicians. In 1309 Arnaldus of Villanova wrote that "It prolongs good health, dissipates superfluous humours, reanimates the heart and maintains youth." In the Late Middle Ages, the production of moonshine started to pick up, especially in the German-speaking regions. By the 13th century, Hausbrand (literally "home-burnt" from gebrannter wein, brandwein; "burnt (distilled) wine") was commonplace and is the origin of brandy. Towards the end of the Late Middle Ages, the consumption of spirits became so ingrained even among the general population that restrictions on sales and production began to appear in the late 15th century. In 1496 the city of Nuremberg issued restrictions on the selling of aquavit on Sundays and official holidays.[22]

Herbs and spices

Spices were among the most luxurious products available in the Middle Ages, the most common being black pepper, cinnamon (and the cheaper alternative cassia), cumin, nutmeg, ginger and cloves. They all had to be imported from plantations in Asia and Africa, which made them extremely expensive. It has been estimated that around 1,000 tons of pepper and 1,000 tons of the other common spices were imported into Western Europe each year during the late Middle Ages. The value of these goods was the equivalent of a yearly supply of grain for 1.5 million people.[23] While pepper was the most common spice, the most exclusive was saffron, and was used as much for its vivid yellow-red color as for its flavor. Spices that have now fallen into some obscurity include grains of paradise, a relation of cardamom which almost entirely replaced pepper in late medieval north French cooking, long pepper, mace, spikenard, galangal and cubeb. Sugar, unlike today, was considered to be a type of spice due to its high cost and humoral qualities.

Common herbs such as sage, mustard, and especially parsley were grown and used in cooking all over Europe, as were caraway, mint, dill and fennel. Anise could be used to flavor fish and chicken dishes and its seeds were served as sugar-coated comfits. Locally grown herbs were more affordable, and also used in upper-class food, but were then usually less prominent or included merely as coloring. A popular modern-day misconception is that medieval cooks used liberal amounts of spices, particularly black pepper, merely to disguise the taste of spoiled meat. A medieval feast was as much a culinary event as it was a display of the host's vast resources and generosity. Most European nobles had a wide selection of fresh or preserved meats, fish or seafood to choose from, and using ruinously expensive spices on cheap, rotting meat would have made little sense.[24]

Sweets and desserts

The term "dessert" comes from the Old French desservir, "to clear a table", literally "to un-serve" and originated during the Middle Ages. It would typically consist of dragées and mulled wine accompanied by aged cheese, and by the Late Middle Ages could also include fresh fruit covered in sugar, honey or syrup and boiled-down fruit pastes. There was a wide variety of fritters, crêpes with sugar, sweet custards and darioles, almond milk and eggs in a pastry shell that could also include fruit and sometimes even bone marrow or fish.[25] German-speaking areas had a particular fondness for krapfen: fried pastries and dough with various sweet and savory fillings. Marzipan in many forms was well-known in Italy and southern France by the 1340s and is assumed to be of Arab origin.[26] Anglo-Norman cookbooks are full of recipes for sweet and savory custards, potages, sauces and tarts with strawberries, cherries, apples and plums. The English chefs also had a penchant for using flower petals of roses and elderberry. An early form of quiche can be found in Forme of Cury, a 14th century recipe collection, as a Torte de Bry with a cheese and egg yolk filling.[27]

In northern France a wide assortment of waffles and wafers was eaten with cheese and hypocras or a sweet malmsey as issue de table ("departure from the table"). The ever-present candied ginger, coriander, aniseed and other spices were referred to as épices de chambre ("parlor spices") and were taken as digestibles at the end of a meal to "close" the stomach.[28] Like their Muslim counterparts in Spain, the Arab conquerors of Sicily introduced a wide variety of new sweets and desserts that eventually found their way to the rest of Europe. Just like Montpellier, Sicily was once famous for its comfits, nougat candy (torrone, or turrón in Spanish) and almond clusters (confetti). From the south, the Arabs also brought the art of ice cream making that produced delightful sherbets and a few marvelous examples of sweet cakes and pastries; cassata alla Siciliana (from Arabic qas'ah, the term for the terra cotta bowl with which it was shaped), made from marzipan, sponge cake and sweetened ricotta and cannoli alla Siciliana, originally cappelli di turchi ("Turkish hats"), fried, chilled pastry tubes with a sweet cheese filling.[29]

Dietary norms

The Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches and their calendars had great influence on eating habits; consumption of meat was forbidden for a full third of the year for most Christians, and all animal products such as eggs and dairy products (but not fish) were generally prohibited during Lent and fast. The church often made exceptions where non-animal alternatives were unavailable or simply unaffordable (e.g. the puffin being considered a fish for coastal fishermen in Norway). Exempt from fasting regulations were children, the old, pilgrims, workers and beggars, but not the poor as long as they had some sort of shelter. Additionally, it was customary for all citizens to fast prior to taking the eucharist, and these fasts were occasionally for a full day and required total abstinence.

Medical science of the Middle Ages had a much greater influence on what was considered healthy and nutritious. One's lifestyle — including diet, exercise, appropriate social behavior, and approved medical remedies — was the way to good health, and all types of food were assigned certain properties that affected a person's health. All foodstuffs were also classified on scales ranging from hot to cold and moist to dry, according to the four bodily humors theory proposed by Galen that dominated Western medical science from late Antiquity until the 17th century.

Medieval dietetics

Medieval scholars considered human digestion to be a process similar to cooking. The processing of food in the stomach was seen as a continuation of the preparation initiated by the cook. In order for the food to be properly "cooked" and for the nutrients to be properly absorbed, it was important that the stomach be filled in an appropriate manner. Easily digestible foods would be consumed first followed by gradually heavier dishes. If this regimen were not respected it was believed that heavy foods would sink to the bottom of the stomach, thus blocking the digestion duct, so that food would digest very slowly and cause putrefaction of the body and draw bad humors into the stomach. It was also of vital importance that food of differing properties not be mixed.[30]

Before a meal, the stomach would preferably be "opened" with an apéritif (from Latin aperire, "to open") that was preferably of a hot and dry nature; confections made from sugar- or honey-coated spices like ginger, caraway and seeds of anise, fennel or cumin, wine and sweetened fortified milk drinks. As the stomach had been opened, it should then be "closed" at the end of the meal with the help of a digestive, most commonly a dragée, which during the Middle Ages consisted of lumps of spiced sugar, or hypocras, a wine flavored with fragrant spices, along with aged cheese.

A meal would ideally begin with easily digestible fruit, such as apples. It would then be followed by vegetables such as lettuce, cabbage, purslane, herbs, moist fruits, light meats like chicken or goat kid with potages and broths. Later would be consumed heavy meats such as pork and beef, as well as vegetables and nuts like pears and chestnuts, both considered difficult to digest. It was popular (and recommended by medical expertise) to finish the meal with aged cheese and various digestives.[31]

See also

Notes

- ^ Henisch chapter 2

- ^ Adamson pg. 161–164,

- ^ Henisch pg. 185–186

- ^ Adamson, Chapter 2: Food Preparation

- ^ Scully pg. 113

- ^ Scully pg. 44-46

- ^ Scully pg. 70

- ^ Medieval science...; Food storage and preservation

- ^ Early pies had bottom crusts that were not intended to be eaten. The modern equivalent of a pie, with a completely edible crust, was not conceived until the 14th century.

- ^ Scully pg. 35–38

- ^ Adamson pg. 161–164

- ^ Cabbage and other foodstuffs in common use by most German-speaking peoples are mentioned in Walther Ryff's dietary from 1549 and Hieronymus Bock's Deutsche Speißkamer ("German Larder") from 1550, see Regional Cuisines pg. 163

- ^ a b c Adamson chapter 1

- ^ Regional Cuisines pg. 89

- ^ Adamson pg. 164

- ^ The rather contrived notion of the non-animal classification of barnacle geese was not universally accepted. The Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II examined barnacles and noted the lack of any evidence of any bird-like embryo in them, and the secretary of Leo of Rozmital provided a highly skeptical account of his reactions to being served barnacle goose at a fish-day dinner in 1456; Henisch pg. 48-49.

- ^ Adamson pg. 48–51

- ^ Scully pg. 154-157

- ^ Scully pg. 138–146

- ^ Scully pg. 151-154

- ^ Medieval Science...; Brewing

- ^ Scully pg. 157-165

- ^ Adamson pg. 65; by comparison, the estimated population of Britain in 1340, right before the Black Death was only 5 million and a mere 3 million by 1450 (Fontana pg. 36)

- ^ Scully pg. 84-86

- ^ Scully 135-136

- ^ Adamson pg. 89

- ^ Adamson pg. 97

- ^ Adamson pg. 110

- ^ Regional Cuisines pg. 120-121

- ^ Scully pg. 135-136

- ^ Scully pg. 126-135

References

- Adamson, Melitta Weiss (2004) Food in Medieval Times ISBN 0-313-32147-7

- The Fontana Economic History of Europe: The Middle Ages (1972); J.C Russel Population in Europe 500-1500 ISBN 0-00-632841-5

- Henisch, Bridget Ann (1976), Fast and Feast: Food in Medieval Society ISBN 0-271-01230-7

- Medieval science, technology, and medicine : an encyclopedia (2005) Thomas Glick, Steven J. Livesey, Faith Wallis, editors ISBN 0-415-96930-1

- Regional Cuisines of Medieval Europe: A Book of Essays (2002), edited by Melitta Weiss Adamson ISBN 0-415-92994-6

- Scully, Terence (1995) The Art of Cookery in the Middle Ages ISBN 0-85115-611-8

External links

- Le Viandier de Taillevent - An online translation of the 14th century cookbook by James Prescott

- How to Cook Medieval - A guide on how to make medieval cuisine with modern ingredients

- The Forme of Cury - A late 14th century English cookbook, available from Project Gutenberg

- Cariadoc's Miscellany, a collection of articles and recipes on medieval and Renaissance food

- MedievalCookery.com - Recipes, information, and notes about cooking in medieval Europe.

- Getting your bread in medieval society

- Feeding the poor in medieval Catalonia

- Nutrition and the Early-Medieval Diet

- Dietary Requirements of the Medieval Peasant

- Making Medieval Sauces