Nicotine marketing: Difference between revisions

Fails WP:NFCC#8, because there is no relevant text discussing the image or its marketing message. |

rmv policy violations and unreliable sources |

||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

====Products claiming reduced harms==== |

====Products claiming reduced harms==== |

||

To imply that some types of cigarettes are healthier than others, marketing also uses brand descriptors such as "light", "mild", "natural", "gentle", "calm", "soft", and "smooth".<ref name=FDA_review/>{{rp|62–65}}<ref name=media_role/>{{rp|}} Switching to a product branded to suggest that it is less harmful or addictive ([[Lights (cigarette type)|"mild", "light", "low-tar", "filtered" etc.]]) is, in terms of health effects, meaningless.<ref name=adolescent_light>{{cite journal |doi=10.1542/peds.2004-0893 |pmid=15466070 |title=Adolescents' Beliefs About the Risks Involved in Smoking 'Light' Cigarettes |journal=Pediatrics |volume=114 |issue=4 |pages=e445–51 |year=2004 |last1=Kropp |first1=R. Y |last2=Halpern-Felsher |first2=B. L }}</ref><ref name="National Cancer Institute">{{Cite web| last = National Cancer Institute| title = "Light" Cigarettes and Cancer Risk| work = National Cancer Institute| format = cgvFactSheet| accessdate = 2018-05-23| url = https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/tobacco/light-cigarettes-fact-sheet}}</ref><ref name="The fallacy of light cigarettes">{{cite journal |doi=10.1136/bmj.328.7440.E278 |pmid=15016715 |pmc=2901853 |title=The fallacy of 'light' cigarettes |journal=BMJ |volume=328 |issue=7440 |pages=E278–9 |year=2004 |last1=Rigotti |first1=Nancy A |last2=Tindle |first2=Hilary A }}</ref><ref name=filters_dangerous>{{cite journal |doi=10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i40 |pmid=11893814 |pmc=1766061 |title=Cigarette filter ventilation is a defective design because of misleading taste, bigger puffs, and blocked vents |journal=Tobacco Control |volume=11 |pages=I40–50 |year=2002 |last1=Kozlowski |first1=L T |last2=O'Connor |first2=R J }}</ref> [[Menthol cigarettes]] are also marketed as healthier (by implication, using words like "mild", "natural", "gentle", "calm", "soft", "smooth", and imagery of healthy natural environments).<ref name=FDA_review/>{{rp|62–65}} There is no evidence that menthol cigarettes are healthier, but there is evidence that they are somewhat easier to become addicted to and harder to quit.<ref name=FDA_review/>{{rp|25–27}} Ventilated cigarettes (marketed as "light" etc.) do feel cooler, airier, and less harsh, and a smoking machine will give lower tar and nicotine readings for them. But they do not actually reduce human intake or health risks, as a human responds to the lower resistance to breathing through them by taking bigger puffs.<ref name=filters_dangerous/> They were also designed to be equally addictive, as manufacturers did not want to lose customers.<ref name=darklite>{{cite journal |doi=10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i18 |pmid=11893811 |pmc=1766068 |title=The dark side of marketing seemingly 'Light' cigarettes: Successful images and failed fact |journal=Tobacco Control |volume=11 |pages=I18–31 |year=2002 |last1=Pollay |first1=R W |last2=Dewhirst |first2=T }}</ref> |

To imply that some types of cigarettes are healthier than others, marketing also uses brand descriptors such as "light", "mild", "natural", "gentle", "calm", "soft", and "smooth".<ref name=FDA_review/>{{rp|62–65}}<ref name=media_role/>{{rp|}} Switching to a product branded to suggest that it is less harmful or addictive ([[Lights (cigarette type)|"mild", "light", "low-tar", "filtered" etc.]]) is, in terms of health effects, meaningless.<ref name=adolescent_light>{{cite journal |doi=10.1542/peds.2004-0893 |pmid=15466070 |title=Adolescents' Beliefs About the Risks Involved in Smoking 'Light' Cigarettes |journal=Pediatrics |volume=114 |issue=4 |pages=e445–51 |year=2004 |last1=Kropp |first1=R. Y |last2=Halpern-Felsher |first2=B. L }}</ref><ref name="National Cancer Institute">{{Cite web| last = National Cancer Institute| title = "Light" Cigarettes and Cancer Risk| work = National Cancer Institute| format = cgvFactSheet| accessdate = 2018-05-23| url = https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/tobacco/light-cigarettes-fact-sheet}}</ref><ref name="The fallacy of light cigarettes">{{cite journal |doi=10.1136/bmj.328.7440.E278 |pmid=15016715 |pmc=2901853 |title=The fallacy of 'light' cigarettes |journal=BMJ |volume=328 |issue=7440 |pages=E278–9 |year=2004 |last1=Rigotti |first1=Nancy A |last2=Tindle |first2=Hilary A }}</ref><ref name=filters_dangerous>{{cite journal |doi=10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i40 |pmid=11893814 |pmc=1766061 |title=Cigarette filter ventilation is a defective design because of misleading taste, bigger puffs, and blocked vents |journal=Tobacco Control |volume=11 |pages=I40–50 |year=2002 |last1=Kozlowski |first1=L T |last2=O'Connor |first2=R J }}</ref> [[Menthol cigarettes]] are also marketed as healthier (by implication, using words like "mild", "natural", "gentle", "calm", "soft", "smooth", and imagery of healthy natural environments).<ref name=FDA_review/>{{rp|62–65}} There is no evidence that menthol cigarettes are healthier, but there is evidence that they are somewhat easier to become addicted to and harder to quit.<ref name=FDA_review/>{{rp|25–27}} Ventilated cigarettes (marketed as "light" etc.) do feel cooler, airier, and less harsh, and a smoking machine will give lower tar and nicotine readings for them. But they do not actually reduce human intake or health risks, as a human responds to the lower resistance to breathing through them by taking bigger puffs.<ref name=filters_dangerous/> They were also designed to be equally addictive, as manufacturers did not want to lose customers.<ref name=darklite>{{cite journal |doi=10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i18 |pmid=11893811 |pmc=1766068 |title=The dark side of marketing seemingly 'Light' cigarettes: Successful images and failed fact |journal=Tobacco Control |volume=11 |pages=I18–31 |year=2002 |last1=Pollay |first1=R W |last2=Dewhirst |first2=T }}</ref> |

||

E-cigarettes are also marketed as an intelligent alternative to quitting for [[Nicotine marketing#unwilling smokers|unwilling smokers]], and make health claims.<ref>http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images_ecigs.php?token2=fm_ecigs_st437.php&token1=fm_ecigs_img21854.php&theme_file=fm_ecigs_mt053.php&theme_name=Smart,%20Pure%20&%20Fresh&subtheme_name=Smarter</ref>{{unreliable-inline|date=June 2018}}<ref name=FDA_review/>{{rp|62-63}}{{FV|date=June 2018}} As once with the similarly-marketed{{SYN|date=June 2018}} "lite" cigarettes<ref name=darklite/>{{SYN|date=June 2018}} and menthol cigarettes<ref name=FDA_review/>{{SYN|date=June 2018}} there are concerns that they might delay and deter quitting, by giving users an excuse to keep using nicotine.<ref name=Grana2014>{{cite journal |doi=10.1161/circulationaha.114.007667 |pmid=24821826 |pmc=4018182 |title=E-Cigarettes: A Scientific Review |journal=Circulation |volume=129 |issue=19 |pages=1972–86 |year=2014 |last1=Grana |first1=R |last2=Benowitz |first2=N |last3=Glantz |first3=S. A }}</ref>{{Relevance inline|date=June 2018}}<ref name="Kalkhoran2016">{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/s2213-2600(15)00521-4 |pmid=26776875 |pmc=4752870 |title=E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis |journal=The Lancet Respiratory Medicine |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=116–28 |year=2016 |last1=Kalkhoran |first1=Sara |last2=Glantz |first2=Stanton A }}</ref> |

|||

{{failed verification span|text=Marketing often claims that |date=June 2018}} e-cigarettes are less harmful than combustible cigarettes.<ref>{{Cite web| title = Evidence review of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products 2018: executive summary| work = GOV.UK| accessdate = 2018-06-03| url = https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/e-cigarettes-and-heated-tobacco-products-evidence-review/evidence-review-of-e-cigarettes-and-heated-tobacco-products-2018-executive-summary}}</ref> Some other often implicit marketing claims made both online and by some [[sales rep]]s in vape shops are that<ref name=vape_shops>{{Cite web| title = Vape Shops Clouding Issues of Safety| work = Truth In Advertising| accessdate = 2018-05-26| date = 2016-05-24| url = https://www.truthinadvertising.org/vape-shops-clouding-issues-safety/}}</ref>{{unreliable-inline|date=June 2018}}<ref name=Grana2014/>{{FV|date=June 2018}} |

|||

* e-cigarettes are harmless, or even beneficial, to the user, compared with not smoking<ref name=Grana2014/><ref name=England2015/><ref name=vape_shops/>{{unreliable-inline|date=June 2018}}<ref name=adverse_effects>See also a reference list [[:File:Adverse effects of vaping (raster).png#Summary|here]] on the adverse effects of vaping</ref>{{Relevance inline|date=June 2018}} |

|||

* e-cigarettes are harmless to others breathing the same air<ref name=Grana2014/><ref name=standford_bystanders>http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images_ecigs.php?token2=fm_ecigs_st387.php&token1=fm_ecigs_img17157.php&theme_file=fm_ecigs_mt036.php&theme_name=Healthier&subtheme_name=Second%20Hand</ref>{{unreliable-inline|date=June 2018}} |

|||

* e-cigarettes [[Electronic cigarette#Smoking cessation|help smokers quit]] (weak evidence);{{Relevance inline|date=June 2018}}<ref name="Cochrane2016">{{cite journal |last1=Hartman-Boyce |first1=Jamie |last2=McRobbie | first2=Hayden | last3=al | first3=et |title=Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation |journal=Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |date=2016 |volume=9 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub3 | pmid=27622384 | page=CD010216}}</ref><ref name=vape_shops/>{{unreliable-inline|date=June 2018}} {{Relevance inline|date=June 2018}} |

|||

The evidence for these claims is weak to negative.{{Relevance inline|date=June 2018}}{{SYN|date=June 2018}}<ref>see individual per-bullet-point refs</ref> Nonsmokers are more likely to start vaping if they think e-cigarettes are not very harmful or addictive; beliefs about harmfullness and addiction don't affect the probability that smokers will start vaping.{{Relevance inline|date=June 2018}}<ref name=nonsmokers_vaping>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.11.027| issn = 1879-0046| volume = 186| pages = 257–263| last1 = Cooper| first1 = Maria| last2 = Loukas| first2 = Alexandra| last3 = Case| first3 = Kathleen R.| last4 = Marti| first4 = C. Nathan| last5 = Perry| first5 = Cheryl L.| title = A longitudinal study of risk perceptions and e-cigarette initiation among college students: Interactions with smoking status| journal = Drug and Alcohol Dependence| date = 2018| pmid = 29626778| pmc = 5911205}}</ref><ref name=harm_addiction>{{cite journal |doi=10.1542/peds.2015-4306 |pmid=27940754 |pmc=5079074 |title=Perceptions of e-Cigarettes and Noncigarette Tobacco Products Among US Youth |journal=Pediatrics |volume=138 |issue=5 |pages=e20154306 |year=2016 |last1=Amrock |first1=Stephen M |last2=Lee |first2=Lily |last3=Weitzman |first3=Michael }}</ref>{{Relevance inline|date=June 2018}} |

|||

== Targets == |

== Targets == |

||

Revision as of 15:56, 21 June 2018

| Part of a series on |

| Tobacco |

|---|

|

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (May 2018) |

Nicotine marketing is the marketing of nicotine-containing products or use. Traditionally, the tobacco industry markets cigarette smoking, but it is increasingly marketing other products, such as e-cigarettes. Products are marketed through social media, stealth marketing, mass media, and sponsorship (particularly of sporting events). Expenditures on nicotine marketing are in the tens of billions a year; in the US alone, spending was over US$ 1million per hour in 2016;[1] in 2003, per-capita marketing spending was $290 per adult smoker, or $45 per inhabitant. Nicotine marketing is increasingly regulated; some forms of nicotine advertising are banned in many countries. The World Health Organization recommends a complete tobacco advertising ban.[2]

Effects

The effectiveness of tobacco marketing is widely documented;[3] tobacco marketing increases consumption. Ads cause new people to become addicted, mostly when they are minors.[4][5][6][3] Ads also keep established smokers from quitting. Advertising peaks in January, when the most people are trying to quit, although the most people take up smoking in the summer.[3]: 61

The tobbaco industry has frequently claimed that ads are only about "brand preference", encouraging existing smokers to switch to and stick to their brand.[7] There is, however, substantial evidence that ads cause people to become, and stay, addicted.[7]

Marketing is also used to oppose regulation of nicotine marketing and other tobacco control measures, both directly and indirectly, for instance by improving the image of the nicotine industry and reducing criticism from youth and community groups. Industry charity and sports sponsorships are publicized (with publicity costing up to ten times the cost of the publicized act), portraying the industry as actively sharing the values of the target audience. Marketing is also used to normalize the industry ("Just Another Fortune 500 Company", "More Than a Tobacco Company").[3]: 198–201 Finally, marketing is used to give the impression that nicotine companies are responsible, "Open and Honest". This is done through an emphasis on informed choice and "anti-teen-smoking" campaigns,[3]: 198–201 although such ads have been criticized as counterproductive (causing more smoking) by independent groups.[3]: 190–196 [8]

Magazines, but not newspapers, that get revenue from nicotine advertising are less likely to run stories critical of nicotine products. Internal documents also show that the industry used its influence with the media to shape coverage of news, such as a decision not to mandate health warnings on cigarette packages or a debate over advertising restrictions.[3]: 345–350

Counter-marketing is also used, mostly by public health groups and governments. The addictiveness and health effects of tobacco use are generally described, as these are the themes missing from pro-tobacco marketing.[3]: 150

Regulation and evasion techniques

Because it harms public health, nicotine marketing is increasingly regulated.

Advertising restrictions typically shift marketing spending to unrestricted media. Banned on television, ads move to print; banned in all conventional media, ads shift to sponsorships; banned as in-store advertising and packaging, advertising shifts to shill (undisclosed) marketing reps, sponsored online content, viral marketing, and other stealth marketing techniques.[3]: 272–280 Unlike conventional advertising, stealth marketing is not openly attributed to the organization behind it. This neutralizes mistrust of tobacco companies, which is widespread among children and the teenagers who provide the industry with most new addicts.[3]: Ch.6&7

Another method of evading restrictions is to sell less-regulated nicotine products instead of the ones for which advertising is more regulated. For instance, while TV ads of cigarettes are banned in the United States, similar TV ads of e-cigarettes are not.[9]

The most effective media are usually banned first, meaning advertisers need to spend more money to addict the same number of people.[3]: 272 Comprehensive bans can make it impossible to effectively substitute other forms of advertising, leading to actual falls in consumption.[3]: 272–280 However, skillful use of allowed media can increase advertising exposure; the exposure of U.S. children to nicotine advertising is increasing as of 2018.[9]

Methods

Rebellion

Nicotine marketing makes extensive use of reactance, the feeling that one is being unreasonably controlled. Reactance often motivates rebellion, in behaviour or belief, which demonstrates that the control was ineffective, restoring the feeling of freedom.[10]

Ads thus rarely explicitly tell the viewer to use nicotine; this has been shown to be counter-productive. Instead, they frequently suggest using as a way to rebel and be free.[10] Mention of addiction is avoided.

Reactance can be eliminated by successfully concealing attempts to manipulate or control behaviour. Unlike conventional advertising, stealth marketing is not openly attributed to the organization behind it. This neutralizes mistrust of tobacco companies, which is widespread among children and the teenagers who provide the industry with most new addicts.[3]: Ch.6&7 The internet and social media are particularly suited to stealth and viral marketing, which is also cheap;[11] nicotine companies now spend tens of millions per year on online marketing.[12]

Counter-advertising also shows awareness of reactance; it rarely tells the viewer what to do. More commonly, it cites statistics about addictiveness and other health effects. Some anti-smoking ads dramatise the statistics (e.g. by piling 1200 body bags in front of the New York headquarters of Philip Morris, now Altria, to illustrated the number of people dying daily from smoking);[13] others document individual experiences.[14] Providing information does not generally provoke reactance.

Social conformity

Despite products being marketed as individualistic and non-conformist, people generally actually start using due to peer pressure. Being offered a cigarette is one of the largest risk factors for smoking.[3]: 256–257 Boys with a high degree of social conformity are also more likely to start smoking.[3]: 216

Social pressure is deliberately used in marketing, often using stealth marketing techniques to avoid triggering reactance. "Roachers", selected for good looks, style, charm,[3]: 110 and being slightly older than the targets,[15] are hired to offer samples of the product.[3]: 110 "Hipsters" are also recruited clandestinely from the bar and nightclub scene to sell cigarettes, and ads are placed in alternative media publications with "hip credibility".[3]: 108–110 Other strategies include sponsoring bands and seeking to give an impression of usage by scattering empty cigarette packages.[16].

Ads also use the threat of social isolation, implied or explicit (e.g. "Nobody likes a quitter").[17] Great care is taken to maintain the impression that a brand is popular and growing in popularity, and that people who smoke the brand are popular[3]: 217

Marketing seeks to create a desirable identity as a user, or a user of a specific brand. It seeks to associate nicotine use with rising social identities (see, for instance, the history of tobacco advertising in the woman's and civil rights movements, and its use of western affluence in the developing world, below). It also seeks to associate nicotine use with positive traits, such as intelligence, fun, sexiness, sociability, high social status, wealth, health, athleticism, and pleasant outdoor pursuits. Many of these associations are fairly implausible; smoking is not generally considered an intelligent choice, even by smokers; most smokers feel miserable about smoking,[18] smoking causes impotence,[19][20][21][22] many smokers feel socially stigmatized for smoking,[18] and smoking is expensive and unhealthy.

Marketing also uses associations with loyalty, which not only defend a brand, but put a positive spin on not quitting. A successful campaign playing on loyalty and identity was the "rather fight than switch" campaign, in which the makeup the models wore made it seem as if they had black eyes, by implication from a fight with smokers of other cigarettes (campaign by a subsidiary of American Tobacco Company, now owned by British American Tobacco).[23]

Mood changes

Nicotine is also advertised as good for "nerves", irritability, and stress. Again, ads have moved from explicit claims ("Never gets on your nerves") to implicit claims ("Slow down. Pleasure up"). It is certainly true that nicotine products temporarily relieve nicotine withdrawal symptoms.[24][25]

It is thought that nicotine withdrawal is worse for those who are already stressed or depressed, making quitting more difficult.[24][25] About 40% of the cigarettes sold in the U.S. are smoked by people with mental health issues. Smoking rates in the U.S. military were also high, and over a third started smoking after entering the military; deployment was also a risk factor.[26] Disabled people are more likely to smoke; smoking causes disability, but the stress of disability might also cause smoking[27]

According to the CDC Tobacco Product Use Among Adults 2015 report, people who are American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic, less-educated (0–12 years education; no diploma, or General Educational Development), lower-income (annual household income <$35,000), Lesbian, gay, or bisexual, the uninsured, and those under serious psychological distress have the highest reported percentage of any tobacco product use.[28]

Clearly, the sole reason for B&W's interest in the black and Hispanic communities is the actual and potential sales of B&W products within these communities and the profitability of those sales... Consistency and dominance is a acutely necessary in addressing the minority community because of its relatively small size and highly developed methods of informal communications. If B&W were to send conflicting signals to the smaller arena of the minority community, inconsistencies would be far more noticeable. However, this relatively small and often tightly knit [minority] community can work to B&W's marketing advantage, if exploited properly. Peer pressure plays a more important role in many phases of life in the minority community. Therefore, dominance of the marketplace and the community environment is necessary to successfully increase sales share.

Brown & Williamson, a now-defunct subsidiary of British American Tobacco (7 September 1984). Total minority marketing plan (Report)., also cited in [29]

Poorer people also smoke more. When marketing cigarettes to the developing world, tobacco companies associate their product with an affluent Western lifestyle.[30] However, in the developed world, smoking has almost vanished among the affluent. Smoking rates among the American poor are much higher than among the rich, with rates of over 40% for those with a high school equivalency diploma.[31] These differences have been attributed to both lack of healthcare and to selective marketing to socio-economic, racial, and sexual minorities.[31][32] The tobacco industry targeted young rural men by creating advertisements with images of cowboys, hunters, and race car drivers. Teens in rural areas are less likely to be exposed to anti-tobacco messages in the media. Low-income and predominantly minority neighborhoods often have more tobacco retailers and more tobacco advertising than other neighborhoods.[33]

The tobacco industry has marketed heavily to African Americans,[29] sexual minorities,[34] and even the homeless and the mentally ill.[35]

In 1995, Project SCUM, which targeted sexual and racial minorities and homeless people in San Francisco, was planned by R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (a British American Tobacco subsidiary).[36][37]

The tobacco industry focusses marketing towards vulnerable groups, contributing to the large disparity in smoking and health problems.[38]

Tobacco companies have often been progressive in their hiring policies, employing women and blacks when this was controversial. They also donate some of their profits to a variety of organisations that help people in need.[39][29]

Non-addictiveness and healthiness

[new marketing approaches should] "create brands and products which reassure consumers, by answering to their needs. Overall marketing policy will be such that we maintain faith and confidence in the smoking habit... All work in this area [communications] should be directed towards providing consumer reassurance about cigarettes and the smoking habit... by claimed low deliveries, by the perception of low deliveries and by the perception of 'mildness'. Furthermore, advertising for low delivery or traditional brands should be constructed in ways so as not to provoke anxiety about health, but to alleviate it, and enable the smoker to feel assured about the habit and confident in maintaining it over time"

British American Tobacco. Emphasis in original[40]

Reference to the addictiveness of nicotine is avoided in marketing.[41]: 150

The nicotine industry frequently markets its products as healthy, safe, and harmless; it has even marketed them as beneficial to health. These marketing messages were initially explicit, but over the decades, they became more implicit and indirect. Explicitly claiming something that the consumer knows to be untrue tend to make them distrust and reject the message, so the effectiveness of explicit claims dropped as evidence of the harms of cigarettes became more widely known. Explicit claims also have the disadvantage that they remind smokers of the health harms of the product.[41]: 63

Implicit claims include slogans with connotations of health and vitality, such as "Alive with pleasure", and imagery (of instance, images of athletic, healthy people, the presence of healthy children, healthy natural environments, and medical settings).[41]: 62–65 [3]

Products claiming reduced harms

To imply that some types of cigarettes are healthier than others, marketing also uses brand descriptors such as "light", "mild", "natural", "gentle", "calm", "soft", and "smooth".[41]: 62–65 [3] Switching to a product branded to suggest that it is less harmful or addictive ("mild", "light", "low-tar", "filtered" etc.) is, in terms of health effects, meaningless.[42][43][44][45] Menthol cigarettes are also marketed as healthier (by implication, using words like "mild", "natural", "gentle", "calm", "soft", "smooth", and imagery of healthy natural environments).[41]: 62–65 There is no evidence that menthol cigarettes are healthier, but there is evidence that they are somewhat easier to become addicted to and harder to quit.[41]: 25–27 Ventilated cigarettes (marketed as "light" etc.) do feel cooler, airier, and less harsh, and a smoking machine will give lower tar and nicotine readings for them. But they do not actually reduce human intake or health risks, as a human responds to the lower resistance to breathing through them by taking bigger puffs.[45] They were also designed to be equally addictive, as manufacturers did not want to lose customers.[40]

Targets

Unwilling smokers: customer retention

Smokers mostly want to quit and can't.[18][46] On average, smokers start as adolescents and make over 30 quit attempts, at a rate of about 1 per year, before breaking a nicotine addiction in their 40s or 50s.[47] Most say they feel addicted, and feel misery and disgust at their inability to quit (in surveys, 71-91% regret having started, over 80% intend to quit, around 15% plan to quit within the next month).[18] The industry calls this group "concerned smokers" and seeks to retain them as customers.[7] Techniques for lowering their quit rate include dissuading them from wanting to quit and offering them meaningless product choices which help them feel in control of their habit. For instance, downplaying the risks, and encouraging them to take pride in smoking as an identity, reduces desire to quit. Suggesting that they can reduce their risk by choosing to switch to another product (branded to suggest that it is less harmful or addictive) can reduce their cognitive dissonance[41]: 63 and sense of lack of control, without offering a health improvement.[43][44][45][41]: 62–65

Youth: new customers

Younger adult smokers are the only source of replacement smokers. Repeated government studies (Appendix B) have shown that:

- Less than one-third of smokers (31%) start after age 18.

- Only 5% of smoker start after age 24

Thus, today's young adult smoking behavior will largely determine the trend of Industry volume over the next several decades. If younger adults turn away from smoking, the Industry must decline, just as a population that does not give birth will eventually dwindle. In such and environment, a positive RJR sales trend would require disproportionate share gains and/or steep price increases (which could depress volume).

Internal documents of the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, circa 1985, in the collection of Stanford Research Into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising (note that statistics are out-of-date).

Smokers typically start young, often as teenagers. As a result, much cigarette advertising is intended to target youth, and depicts young people smoking and using tobacco as a form of leisure and enjoyment.[2]

Before 2009, many tobacco companies made flavored tobacco packaged often in colorful candy like wrappers to attract new users, many of which were a younger audience. However these flavored cigarettes were banned on September 22, 2009 by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Despite this initiative, flavored cigarettes are still on the rise because tobacco companies change their products slightly so they are filtered or slim cigarettes, which are not banned by the act.[clarification needed][49]

The intended audience of tobacco advertising has changed throughout the years, with some brands specifically targeted towards a particular demographic. According to Reynolds American Inc, the Joe Camel campaign in the United States was created to advertise Camel brand to young adult smokers. Class action plaintiffs and politicians described the Joe Camel images as a "cartoon" intended to advertise the product to people below the legal smoking age. Under pressure from various anti-smoking groups, the Federal Trade Commission, and the U.S. Congress, Camel ended the campaign on 10 July 1997.[citation needed]

Vending machines, individually-sold single cigarettes, and product displays near schools, next to candy and sweet drinks, and at the eye-level of young children are all used around the world to sell nicotine-containing products. Even large brands are frequently advertised in ways that break local regulations.[50][51] In many countries, such marketing methods are not illegal. Where they are illegal, enforcement is often a problem. For instance, Dr. Suresh Kumar Arora, New Delhi's chief tobacco control officer, said: "We were wasting our time fining cigarette vendors and distributors. They had no idea of the law. Most are illiterate. Our teams would tear down posters and in no time, they would be up again because the real culprits were the big tobacco companies – ITC, Philip Morris (now Altria), Godfrey Phillip. I told them to stop giving posters to their dealers otherwise I would drag them through the courts. Since last May, Delhi has been free of tobacco posters, 100% free". He has, however, been unable to keep mobile vendors from illegally selling cigarettes next to schools.[50]

"Harm reduction" advertising

- Stress that smoking is for adults only

- Make it difficult for minors to obtain cigarettes

- Continue having smoking perceived as a legitimate, albeit morally ambiguous adult activity. Smoking should occupy the middle ground between activities that everyone can partake in vs. activities that only the fringe of society embraces.

- Stress that smoking is dangerous.

- Smoking is for people who like to take risks, who are not afraid of taboos, who take life as an adventure to prove themselves.

- Emphasize the ritualistic elements of smoking, particularly fire and smoke.

- Emphasize the individualism/conformity dichotomy

- Stress the popularity of a brand, that choosing it will reinforce your identity and your integration into the group.

Recommendations of the 1991 "Archetype Project", commissioned by Philip Morris (now Altria) from Rapaille Associates: [2]

Some tobacco companies have sponsored ads that claim to discourage teen smoking. Such ads are unregulated. However, these ads have been shown, in independent studies, to increase the self-reported likelihood that teens will start smoking. They also cause adults to see tobacco companies as more responsible and less in need of regulation. Unlike promotional ads, tobacco companies do not track the effects of these ads themselves. These ads differ from independently-produced antismoking ads in that they do not mention the health effects of smoking, and present smoking as exclusively an "adult choice", undesirable "if you're a teen".[3]: 190–196 There is more exposure to industry-sponsored "antismoking" ads than to antismoking ads run by public health agencies.[3]: 189

Tobacco companies have also funded "anti-smoking" groups. On such organization, funded by Lorillard, enters into exclusive sponsorship agreements with sports organisations. This means that no other anti-smoking campaigns are allowed to be involved with the sporting organisation. Such sponsorships have been criticised by health groups.[8]

History

Nicotine marketing has continually developed new techniques in response to historical circumstances, societal and technological change, and regulation. Countermarketing has also changed, in both message and commoness, over the decades, often in response to pro-nicotine marketing.

Pre-1800

The coughing, throat irritation, and shortness of breath caused by smoking are obvious, and tobacco was criticized as unhealthy long before the invention of the clinical study. In the 1604 A Counterblaste to Tobacco, James VI of Scotland and I of England described smoking as "A custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse", and urged his subjects not to use tobacco.[52] In the 1600s, many countries banned its use.[53] Pope Urban VIII issued a 1624 papal bull condemning tobacco and making its use in holy places punishable by excommunication;[54] Pope Benedict XIII repealed the ban one hundred years later.[55]

1800–1880

The first known nicotine advertisement in the United States was for the snuff and tobacco products and was placed in the New York daily paper in 1789. At the time, American tobacco markets were local. Consumers would generally request tobacco by quality, not brand name, until after the 1840s.[56]

Many European tobacco bans were repealed during the Revolutions of 1848.

Cigarettes were first made in Seville, from cigar scraps. British soldiers took up the habit during the Crimean War (1853–1856).[57] The American Civil War in the early 1860s also led to increased demand for tobacco from American soldiers, and in non-tobacco-growing regions.[57]

Public health measures against chewing tobacco (spitting, especially other than in a spitoon, spread diseases such as flu and tuberculosis) increased cigarette consumption.[57]

After the development of color lithography in the late 1870s, collectible picture series were printed onto cigarette cards, previously only used to stiffen the packaging.[56]

In 1913, a cigarette brand was advertised nationally for the first time in the US. RJ Reynolds advertised it as milder than competing cigarettes.[45]

Mass production and temperance, 1880–1914

Pre-rolled cigarettes, like cigars, were initially expensive, as a skilled cigarette roller could produce only about four cigarettes per minute on average[58] Cigarette-making machines were developed in the 1880s, replacing hand-rolling.[59] One early machine could roll 120,000 cigarettes in 10 hours, or 200 a minute.[58][60][61] Mass production revolutionized the cigarette industry.[62] Cigarette companies began to reckon production in millions of cigarettes per day.[56]

Higher production and cheaper cigarettes gave companies an incentive to increase consumption. By the last quarter of the 19th century, magazines carried advertisements for different brands of cigarettes, snuff, and pipe tobacco.[59] Demand for cigarettes rose exponentially, ~doubling every five years in Canada and the US (until demand began to rise even faster, ~tripling during the four years of World War I).[57]: 429, Fig.1

Anti-tobacco movements

In the late 1800s, the temperance movement was strongly involved in anti-tobacco compaigns, and particularly with the prevention of youth smoking. They argued that smoking was addictive, unhealthy, stunted the growth of children, and, in women, was harmful during pregnancy.[63]

By 1890, 26 American states had banned sales to minors. Over the next decade, further restrictions were legislated, including prohibitions on sale; measures were widely circumvented, for instance by selling expensive matches and giving away cigarettes with them, so there were further bans on giving out free samples of cigarettes.[57]

After women won the vote in the early 1900s, temperance groups successfully campaigned for Juvenile Smoking Laws throughout Australia. At this time, most adults there smoked pipes, and cigarettes were used only by juveniles.[63]

1914–1950

World War I

Free or subsidized branded cigarettes were distributed to troops during World War I.[59] Demand for cigarettes in North America, which had been ~doubling every five years, began to rise even faster, ~tripling during the four years of war.[57]: 429, Fig.1

In the face of imminent violent death, the health harms of cigarettes became less of a concern, and there was public support for drives to get cigarettes to the front lines.[63] Billions of cigarettes were distributed to soldiers in Europe by national governments, the YMCA, the Salvation Army, and the Red Cross. Private individuals also donated money to send cigarettes to the front, even from jurisdictions where the sale of cigarettes was illegal. Not giving soldiers cigarettes was seen as unpatriotic.[57]

Interwar

By the time the war was over, a generation had grown up, and a large proportion of adults smoked, making anti-smoking campaigns substantially more difficult.[63] Returning soldiers continued to smoke, making smoking more socially acceptable. Temperance groups began to concentrate their efforts on alcohol.[63] By 1927, American states had repealed all their anti-smoking laws, except those on minors.[57]

Modern advertising was created with the innovative techniques used in tobacco advertising beginning in the 1920s.[65][66]

Advertising in the interwar period consisted primarily of full page, color magazine and newspaper advertisements. Many companies created slogans for their brand and used celebrity endorsements from famous men and women. Some advertisements contained fictional doctors reassuring customers that their specific brand was good for health.[67]

Smoking was also widely seen in films, possibly due to paid product placement.

In 1924, menthol cigarettes were invented,[68] but they were not initially popular, remaining at a few percent of market share until marketing in the fifties.[41]: 35–37

In the 1920s, tobacco companies continued to target women, aiming to increase the number of smokers.[69] At first, in light of the threat of tobacco prohibition from temperance unions, marketing was subtle; it indirectly and deniably suggested that women smoked. Testimonials from smoking female celebrities were used. Ads were designed to "prey on female insecurities about weight and diet", encouraging smoking as a healthy alternative to eating sweets.[70]

Campaigns used the traditional association that smoking was improper for women to advantage. They marketed cigarettes as "Torches of Freedom", and made a dependence-inducing drug a symbol of women's independence. Lung cancer rates in women rose sharply.[71]

In 1929 Edward Bernays, commissioned by the American Tobacco Company to get more women smoking, decided to hire women to smoke their "torches of freedom" as they walked in the Easter Sunday Parade in New York. He was very careful when picking women to march because "while they should be good looking, they should not look too model-y" and he hired his own photographers to make sure that good pictures were taken and then published around the world.[72]

In 1929, the Sturmabteilung, the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, founded a cigarette company as a way to raise funds and make itself less financially dependent on the party leadership. SA members were expected to smoke only SA brands.[73] There is evidence that coercion was used to promote the sale of these cigarettes. Through this scheme, a typical SA unit earned hundreds of Reichsmarks each month.[74] The brand also promoted political ideas, with sets of cigarette cards showing historical army uniforms.[75]

Medical concerns

Of course it is perfectly easy to give up smoking. One would not like to think that one has become such a slave to tobacco that one cannot do without it—a drug which weakens the heart, damages the nerves, gives you cancer and catarrh and so on. Personally I have given up smoking repeatedly.

"On Giving Up Smoking". Punch or The London Charivari. London. 7 November 1934. p. 506.; this was an old joke even in 1934[76]

Skyrocketing European lung cancer rates drew attention from doctors in the twenties and thirties.[77] Lung cancer had been a vanishingly rare disease. Before 1900, there were only 140 documented cases worldwide.[78] Then, suddenly, lung cancer became a leading cause of death in many countries (a status it retains to this day).[78][3]: 4 [better source needed]

Initially, suspicion was cast on causes including road tar, car exhaust, the 1918 flu pandemic, racial mixing, and the use of chemical weapons in World War I. However, in 1929, a statistical analysis strongly linking lung cancer to smoking was published by Fritz Lickint of Dresden. He did a retrospective cohort study showing that those with lung cancer were, disproportionately, smokers. He also found that men got lung cancer at several times the rate of women, and that, in countries where more women smoked, the difference was much smaller.[78] In 1932, a study in Poland came to the same conclusion, pointing out that the geographic and gender patterns of Polish lung cancer deaths matched those of smoking, but no other suggested cause, such as industry or cars (rare in Poland at the time).[78]

The medical community was criticized for its slow response to these findings. One 1932 paper attributed the slow response to smoking being common among doctors, as well as the general population.[77] Some temperance activists had continued to attack tobacco as expensive, addictive, and leading to petty theft. In the thirties, they also began to publicize the medical findings.[63] There was popular awareness these dangers of smoking (see accompanying quote).

World War II

Despite these findings, free and subsidized branded cigarettes were again distributed to Allied troops during World War II.[59]

Cigarettes were included in American soldiers' C-rations, since many tobacco companies sent the soldiers cigarettes for free. Cigarette sales reached an all-time high at this point, as cigarette companies were not only able to get soldiers addicted, but specific brands also found a new loyal group of customers as soldiers who smoked their cigarettes returned from the war.[79]

Nazis came to oppose tobacco us on grounds of "racial hygiene". The well-funded Institute for Tobacco Hazards Research was founded. Some of those working with it were involved in mass murder and unethical medical experiments, and killed themselves at the end of the war, including Karl Astel, the head of the institute. The institute and other organizations directed anti-smoking campaigns at both the general public and doctors. Campaigns included pamphlets, reprints of academic articles and books, and smoking bans in many public places. An industry-funded counter-institute, the Tabacologia medicinalis, was shut down by Leonardo Conti.[78]

Tobacco companies continue to exploit associations with Nazis to fight anti-tobacco measures. Modern Germany has some of Europe's worst tobacco control policies,[78] and more Germans both smoke and die of it in consequence.[80][81]

1945–70

In the late 1940s, scientific evidence that tobacco harmed health mounted.[67]

However, until the 1970s, most tobacco advertising was legal in the United States and most European nations. In the 1940s and 50s, tobacco was a major radio sponsor; in the 1950s and 60s, they became predominantly involved in televison.[3]: 100 In the United States, in the 1950s and 1960s, cigarette brands frequently sponsored television shows—notably To Tell the Truth and I've Got a Secret. Brand jingles were commonly used on radio and television. Major cigarette companies would advertise their brands in popular TV shows such as The Flintstones and The Beverly Hillbillies, which were watched by many children and teens.[82] In 1964, after facing much pressure from the public, The Cigarette Advertising Code was created by the Tobacco companies, which prohibited advertising directed to youth.[83]

Advertising continued to use celebrities and famous athletes. Popular comedian Bob Hope was used to advertise for cigarette companies.[83] The African-American magazine Ebony often used athletes to advertise major cigarette brands.[84]

In the 1950s, manufacturers began adding filter tips to cigarettes to remove some of the tar and nicotine as they were smoked. "Safer," "less potent" cigarette brands were also introduced. Light cigarettes became so popular that, as of 2004, half of American smokers preferred them over regular cigarettes,[85] According to The Federal Government's National Cancer Institute (NCI), light cigarettes provide no benefit to smokers' health.[86][87]

Racial marketing strategies changed during the fifties, with more attention paid to racial market segmentation. The civil rights movement lead to the rise of African-American publications, such as Ebony. This helped tobacco companies to target separate marketing messages by race.[3]: 57 Tobacco companies supported civil rights organizations, and advertised their support heavily. Industry motives were, according to their public statements, to support civil rights causes; according to an independent review of internal tobacco industry documents, they were "to increase African American tobacco use, to use African Americans as a frontline force to defend industry policy positions, and to defuse tobacco control efforts". There had been internal resistance to tobacco sponsorship, and some organizations are now rejecting nicotine funding as a matter of policy.[29]

Race-specific advertising exacerbated small (a few percent) racial differences in menthol cigarette product preferences into large (tens of percent) ones.[88] Menthol cigarettes are somewhat more addictive,[41] and it has been argued that race-specific marketing for a more addictive product is a social injustice.[89][90]

Despite it being illegal at the time, tobacco marketers gave out free cigarette samples to children in black neighbourhoods in the U.S.[91] Similar practices continue in parts of the world; a 2016 study found over 12% of South African students had been given free cigarettes by tobacco company representative, with lower rates in five other subsaharan countries.[92] Worldwide, 1 in 10 children had been offered free cigarettes by a tobacco company representative, according to a 200-2007 survey.[93]

Tobacco companies supported civil rights organizations, and advertised their support heavily. They also hired key figures in the civil rights movement. Industry motives were, according to their public statements, to support civil rights causes; according to an independent review of internal tobacco industry documents, they were "to increase African American tobacco use, to use African Americans as a frontline force to defend industry policy positions, and to defuse tobacco control efforts". Defenses of the industry mounted with the help of vulnerable groups include "our critics are elitist and racist". Some organizations are now rejecting nicotine funding as a matter of policy.[29]

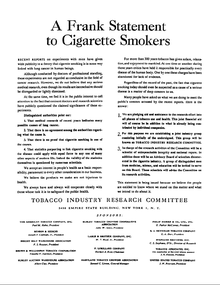

In 1954, tobacco companies ran the ad "A Frank Statement." The ad was the first in a disinformation campaign, disputing reports that smoking cigarettes could cause lung cancer and had other dangerous health effects.[94] It also referred to "research of recent years",[94] although solid statistical evidence of a link between smoking and lung cancer had first been published 25 years earlier.[78]

Prior to 1964, many of the cigarette companies advertised their brand by claiming that their product did not have serious health risks. A couple of examples would be "Play safe with Philip Morris" and "More doctors smoke Camels". Such claims were made both to increase the sales of their product and to combat the increasing public knowledge of smoking's negative health effects.[83] A 1953 industry document claims that the survey brand prefernce among doctors was done on doctors entering a conference, and asked (among a great many camouflage questions) what brand they had on them; marketers had previously placed packs of their Camels in doctors' hotel rooms before the doctors arrived,[95] which probably biassed the results.

In 1964, Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the United States was published. It was based on over 7,000 scientific articles that linked tobacco use with cancer and other diseases. This report led to laws requiring warning labels on tobacco products and to restrictions on tobacco advertisements. As these began to come into force, tobacco marketing became more subtle (for instance, the Joe Camel campaign resulted in increased awareness and uptake of smoking among children).[96] However, restrictions did have an effect on adult quit rates, with its use declining to the point that by 2004, nearly half of all Americans who had ever smoked had quit.[97]

Post-advertising-restrictions; 1970 and later

The period after nicotine advertising restrictions were brought in is characterised by ingenious circumvention of progressively stricter regulations. The industry continued to dispute medical research: denying, for instance, that nicotine was addictive, while deliberately spiking their cigarettes with additional nicotine to make them more addictive.[67]

Advertising restrictions typically shift advertising spending to unrestricted media. Banned on television, ads move to print; banned in all conventional media, ads shift to sponsorships; banned as in-store advertising and packaging, advertising shifts to shill (undisclosed) marketing reps, sponsored online content, viral marketing, and other stealth marketing techniques.[3]: 272–280

Another method of evading restrictions is to sell less-regulated nicotine products instead of the ones for which advertising is more regulated. For instance, while TV ads of cigarettes are banned in the United States, similar TV ads of e-cigarettes are not.[9]

The most effective media are usually banned first, meaning advertisers need to spend more money to addict the same number of people.[3]: 272 Comprehensive bans can make it impossible to effectively substitute other forms of advertising, leading to actual falls in consumption.[3]: 272–280 However, skillful use of allowed media can increase advertising exposure; the exposure of U.S. children to nicotine advertising is increasing as of 2018.[9]

In the US, sport and event sponsorships and billboards became important in the 1970s and 80s, due to TV and radio advertising bans. Sponsors benefit from placing their advertising at sporting events, naming events after themselves, and recruiting political support from sporting agencies. In the 1980s and 90s, these sponsorships were banned in the US and many other countries. Spending has since shifted to point-of-sale advertising and promotional allowances (where legal), direct mail advertising, and Internet advertising. Stealth marketing is also becoming more common,[3]: 100 partly to offset mistrust of the tobacco industry.[3]: Ch.6&7

One major Indian company gives annual bravery awards in its own name; some recipients have rejected or returned them.[98]

Nicotine use is frequently shown in movies. While academics had long speculated that there was paid product placement, it was not until internal industry documents were released that there was hard evidence of such practices.[3]: 363–364 The documents show that in the 1980s and 1990s, cigarettes were shown return for ≤six-figure (US$) sponsorship deals. More money was paid for a star actor to be shown using nicotine. While this sponsorship is now banned in some countries, it is unclear whether the bans are effective, as such deals are generally not publicized or investigated.[3]: 401

Smokers in movies are generally healthier, more successful, and more racially privileged than actual smokers. Health effects, including coughing and addiction, are shown or mentioned in only a few percent of cases, and are less likely to be mentioned in films targeted at younger viewers.[3]: 372–374

In the nineties, internet access expanded in many countries; the web is a major medium for nicotine advertising.

Both Google and Microsoft have policies that prohibit the promotion of tobacco products on their advertising networks.[99][100] However, some tobacco retailers are able to circumvent these policies by creating landing pages that promote tobacco accessories such as cigar humidors and lighters.On Facebook, unpaid content, created and sponsored by tobacco companies, is widely used to advertise nicotine-containing products, with photos of the products, "buy now" buttons and a lack of age restrictions, in contravention of ineffectively enforced Facebook policies.[101][102][103]

In 1998, the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement was reached between the then four largest United States tobacco companies Philip Morris (now Altria), R. J. Reynolds, Brown & Williamson and Lorillard.

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration wrote a major review of menthol cigarettes, which are somewhat more addictive but not healthier,[104] It was subsequently proposed that they should be banned, partially on grounds that race-specific marketing for a more addictive product is racist.Tavernise, Sabrina (13 September 2016). "Black Health Experts Renew Fight Against Menthol Cigarettes". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

E-cigarettes

Advertising tobacco products on TV and radio is banned in many countries, but, in some jurisdictions, the same restrictions do not apply to e-cigarette advertising.[citation needed] Television and radio e-cigarette advertising in some countries may be indirectly advertising traditional cigarette smoking.[105] A 2014 review said, "the e-cigarette companies have been rapidly expanding using aggressive marketing messages similar to those used to promote cigarettes in the 1950s and 1960s."[105] In the US, six large e-cigarette businesses spent $59.3 million on promoting e-cigarettes in 2013.[106]

E-cigarettes are marketed as a alternative to smoking.[105] E-cigarettes are harmless, or even beneficial, to the user are marketing claims.[107] Unsupported claims of safety and quitting smoking are common marketing claims targeted at smokers.[108]

E-cigarettes and nicotine are regularly promoted as safe and beneficial in the media and on brand websites.[107] It is marketed that e-cigarettes emit merely "water vapor".[105] The claim that e-cigarettes produce "only water vapor" is incorrect since the e-cigarette aerosol contains possibly harmful chemicals such as nicotine, carbonyls, heavy metals, and organic volatile compounds, in addition to particulate matter.[109]

E-cigarettes are heavily promoted, mostly via the internet, as a healthy alternative to smoking in the US.[110] Easily circumvented age verification at company websites enables minors to access and be exposed to marketing for e-cigarettes.[111] E-cigarettes are marketed to youth[112] using cartoon characters and candy flavors.[113] E-cigarettes are also marketed on Facebook, where age restrictions are in many cases not implemented.[101]

Celebrity endorsements are also used to encourage e-cigarette use.[114] A national US television advertising campaign starred Steven Dorff exhaling a "thick flume" of what the ad describes as "vapor, not tobacco smoke", exhorting smokers with the message "We are all adults here, it's time to take our freedom back."[115] The ads, in a context of longstanding prohibition of tobacco advertising on TV, were criticized by organizations such as Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids as undermining anti-tobacco efforts.[115] Cynthia Hallett of Americans for Non-Smokers' Rights described the US advertising campaign as attempting to "re-establish a norm that smoking is okay, that smoking is glamorous and acceptable".[115] University of Pennsylvania communications professor Joseph Cappella stated that the setting of the ad near an ocean was meant to suggest an association of clean air with the nicotine product.[115]

Economics

As tobacco companies keep spending money on marketing until it stops being profitable, marginal changes in marketing typically have no measurable effect, but the total amount of marketing has a strong effect.[3]: 276

Econometric studies have been done into the endogeneity[116] and other aspects of bans.[117][118]

Budgets

Tobacco companies have had particularly large budgets for their advertising campaigns. The Federal Trade Commission claimed that cigarette manufacturers spent $8.24 billion on advertising and promotion in 1999, the highest amount ever at that time. The FTC later claimed that in 2005, cigarette companies spent $13.11 billion on advertising and promotion, down from $15.12 billion in 2003, but nearly double what was spent in 1998. The increase, despite restrictions on the advertising in most countries, was an attempt at appealing to a younger audience, including multi-purchase offers and giveaways such as hats and lighters, along with the more traditional store and magazine advertising.[69]

Marketing consultants ACNielsen announced that, during the period September 2001 to August 2002, tobacco companies advertising in the UK spent £25 million, excluding sponsorship and indirect advertising, broken down as follows:

- £11 million on press advertising

- £13.2 million on billboards

- £714,550 on radio advertising

- £106,253 on direct mail advertising

Figures from around that time also estimated that the companies spent £8m a year sponsoring sporting events and teams (excluding Formula One) and a further £70m on Formula One in the UK.[119]

The £25 million spent in the UK amounted to approximately US$0.60 per person in 2002. The 15.12 billion spent in the United States in 2003 amounted to more than $45 for every person in the United States, more than $36 million per day, and more than $290 for each U.S. adult smoker.

Gallery

-

In a 1922 ad, a small child, smoking a cigarette, tells his amused parents not to worry, as he is smoking for a veteran's charity. Children were often used in early cigarette ads, where they helped normalize smoking as part of family living, and gave associations of purity, vibrancy, and life.[120]

-

"We claim no curative powers for Phillip Morris" say this 1943 ad, in the small text. The FDA was prosecuting brands that did for false advertising.

-

This WWII ad shows a mother sending her soldier son a carton of cigarettes, and urges others to do the same. In an echo of the claim that doctors prefer the brand, it claims that men in the military prefer it, too. A mention of War Stamps associates the brand still more closely to war patriotism.

-

Women in the War cigarette ad showing a woman signalling civilian aircraft. The ad associates taking a "man's job" and smokign cigarettes like a man: "Co-ed leaves Campus to fill a Man's job. She's "in the service" -- even to her choice of cigarettes..."

-

1900 cigarette ad; targeting women is not a new strategy

-

Cigar ad claiming that a fictional doctor called this brand "harmless" and "never gets on your nerves" (a term then used for nicotine withdrawal symptoms)

-

Ad showing a fictional doctor endorsing a cigar brand. At the time, it was considered a breach of medical ethics to advertise; doctors who did so would risk losing their license.[121]

-

Belomorkanal – Russian cigarettes

-

Hans Rudi Erdt: Problem Cigarettes, 1912

-

French Painted Mural Advertisement

-

Tobacco display in a store Munich in 2008. In many countries, cigarettes may not be displayed, but must be kept behind the counter.

-

Advertisement for "Murad" Turkish cigarettes 1918

-

Advertisement for "Egyptian Deities" cigarettes 1919

-

Veterans Stadium Philadelphia 1986

-

Early 20th Century Cigarettes in Durham, NC

See also

- Plain tobacco packaging

- Cigarette packets in Australia

- Tobacco marketing and African Americans

- Tobacco packaging warning messages

- Torches of Freedom

- Smoking ban

- WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- Philip Morris v. Uruguay

- Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps

- Jeff Wigand – former tobacco company executive and whistleblower

- Advertising to children

- Tobacco usage in sport

References

- ^ https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/economics/econ_facts/index.htm

- ^ a b WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: The MPOWER Package. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2008. p. 38. ISBN 978 92 4 159628 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj Davis, Ronald M.; Gilpin, Elizabeth A.; Loken, Barbara; Viswanath, K.; Wakefield, Melanie A. (2008). The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use (PDF). National Cancer Institute tobacco control monograph series. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. p. 684.

- ^ Biener L, Siegel M (March 2000). "Tobacco marketing and adolescent smoking: more support for a causal inference". Am J Public Health. 90 (3): 407–11. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.3.407. PMC 1446173. PMID 10705860.

- ^ Choi WS, Ahluwalia JS, Harris KJ, Okuyemi K (May 2002). "Progression to established smoking: the influence of tobacco marketing". Am J Prev Med. 22 (4): 228–33. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00420-8. PMID 11988378.

- ^ Saffer H, Chaloupka F (November 2000). "The effect of tobacco advertising bans on tobacco consumption". J Health Econ. 19 (6): 1117–37. doi:10.1016/S0167-6296(00)00054-0. PMID 11186847.

- ^ a b c Pollay, R. W (2000). "Targeting youth and concerned smokers: Evidence from Canadian tobacco industry documents". Tobacco Control. 9 (2): 136–47. doi:10.1136/tc.9.2.136. PMC 1748318. PMID 10841849.

- ^ a b https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/content/pressoffice/sternletter.pdf

- ^ a b c d Reuters. "More U.S. teens seeing e-cigarette ads". Business Insider. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Grandpre, Joseph; Alvaro, Eusebio M; Burgoon, Michael; Miller, Claude H; Hall, John R (2003). "Adolescent Reactance and Anti-Smoking Campaigns: A Theoretical Approach". Health Communication. 15 (3): 349–66. doi:10.1207/S15327027HC1503_6. PMID 12788679.

- ^ Maria Woerndl; Savvas Papagiannidis; Michael Bourlakis; Feng Li (2008). "Internet-induced marketing techniques: Critical factors in viral marketing campaigns". International Journal of Business Science and Applied Management. 3 (1).

- ^ TOBACCO PRODUCT MARKETING ON THE INTERNET (PDF), retrieved 25 May 2018

- ^ Newman, Andrew Adam (10 August 2014). "A Less Defiant Tack in a Campaign to Curb Smoking by Teenagers". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Newman, Andrew Adam (24 July 2014). "Hard-to-Watch Commercials to Make Quitting Smoking Easier". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Recommendations of the 1991 "Archetype Project", commissioned by Philip Morris (now Altria) from Rapaille Associates: [1]

- ^ Except from an internal industry document, in the collection of Stanford Research Into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising

- ^ Source for example quote: File:No-one_likes_a_quitter,_e-cigarette_ad.jpg This 2011 e-cigarette ad plays on social anxieties with the phrase "Nobody likes a quitter". The ad is explicitly addressed at the "concerned smoker", someone considering quitting, and it suggests a more harmful alternative to quitting.

- ^ a b c d Pechacek, Terry Frank; Nayak, Pratibha; Slovic, Paul; Weaver, Scott R; Huang, Jidong; Eriksen, Michael P (2017). "Reassessing the importance of 'lost pleasure' associated with smoking cessation: Implications for social welfare and policy". Tobacco Control: tobaccocontrol-2017-053734. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053734. PMID 29183920.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20060715183626/[full citation needed]

- ^ Peate I (2005). "The effects of smoking on the reproductive health of men". British Journal of Nursing. 14 (7): 362–6. doi:10.12968/bjon.2005.14.7.17939. PMID 15924009.

- ^ "The Tobacco Reference Guide". Archived from the original on 15 July 2006. Retrieved 15 July 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kendirci M, Nowfar S, Hellstrom WJ (January 2005). "The impact of vascular risk factors on erectile function". Drugs of Today. 41 (1): 65–74. doi:10.1358/dot.2005.41.1.875779. PMID 15753970.

- ^ Elliott, Stuart (6 February 2004). "James J. Jordan, advertising sloganeer, dies at 73". New Your Times. NYTimes.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2006. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Parrott, Andrew C (2009). "Cigarette-Derived Nicotine is not a Medicine". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 4 (2): 49–55. doi:10.3109/15622970309167951. PMID 12692774.

- ^ a b Parrott, Andrew C (2006). "Nicotine psychobiology: How chronic-dose prospective studies can illuminate some of the theoretical issues from acute-dose research". Psychopharmacology. 184 (3–4): 567–76. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-0294-y. PMID 16463194.

- ^ Wan, William (24 August 2017). "New ads accuse Big Tobacco of targeting soldiers and people with mental illness". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/resources/data/cigarette-smoking-in-united-states.html[full citation needed]

- ^ Phillips, Elyse; Wang, Teresa W; Husten, Corinne G; Corey, Catherine G; Apelberg, Benjamin J; Jamal, Ahmed; Homa, David M; King, Brian A (2017). "Tobacco Product Use Among Adults — United States, 2015". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 66 (44): 1209–1215. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6644a2. PMC 5679591. PMID 29121001.

- ^ a b c d e Yerger, V B; Malone, R. E (2002). "African American leadership groups: Smoking with the enemy". Tobacco Control. 11 (4): 336–45. doi:10.1136/tc.11.4.336. PMC 1747674. PMID 12432159.

- ^ Nichter, Mark; Cartwright, Elizabeth (1991). "Saving the Children for the Tobacco Industry". Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 5 (3): 236–56. doi:10.1525/maq.1991.5.3.02a00040. JSTOR 648675.

- ^ a b Wan, William (13 June 2017). "America's new tobacco crisis: The rich stopped smoking, the poor didn't". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ "#STOPPROFILING: Tobacco is a social justice issue". Truth Initiative. 9 February 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ Health, CDC's Office on Smoking and. "CDC - Tobacco-Related Disparities - Tobacco Use by Geographic Region - Smoking & Tobacco Use". Smoking and Tobacco Use. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ Lee, J G L; Griffin, G K; Melvin, C L (2009). "Tobacco use among sexual minorities in the USA, 1987 to May 2007: A systematic review". Tobacco Control. 18 (4): 275–82. doi:10.1136/tc.2008.028241. PMID 19208668.

- ^ Apollonio, D E; Malone, R. E (2005). "Marketing to the marginalised: Tobacco industry targeting of the homeless and mentally ill". Tobacco Control. 14 (6): 409–15. doi:10.1136/tc.2005.011890. PMC 1748120. PMID 16319365.

- ^ San Francisco - News - Smoking Gun: Tobacco industry documents expose an R.J. Reynolds marketing plan targeting S.F. gays and homeless people. Its name: Project SCUM., by Joel P. Engardio, Wednesday, May 2, 2001

- ^ Original document from Project SCUM, from the collection of Stanford Research Into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising

- ^ Baig, Sabeeh A; Pepper, Jessica K; Morgan, Jennifer C; Brewer, Noel T (2017). "Social identity and support for counteracting tobacco company marketing that targets vulnerable populations". Social Science & Medicine. 182: 136–141. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.052. PMC 5474382. PMID 28427731.

- ^ Rosenblatt, Roger (20 March 1994). "How Do Tobacco Executives Live With Themselves?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ^ a b Pollay, R W; Dewhirst, T (2002). "The dark side of marketing seemingly 'Light' cigarettes: Successful images and failed fact". Tobacco Control. 11: I18–31. doi:10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i18. PMC 1766068. PMID 11893811.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) of the Center for Tobacco Products of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (21 July 2011). Menthol Cigarettes and Public Health: Review of the Scientific Evidence and Recommendations (PDF). US Food and Drug Administration. p. 252. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Kropp, R. Y; Halpern-Felsher, B. L (2004). "Adolescents' Beliefs About the Risks Involved in Smoking 'Light' Cigarettes". Pediatrics. 114 (4): e445–51. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0893. PMID 15466070.

- ^ a b National Cancer Institute. ""Light" Cigarettes and Cancer Risk" (cgvFactSheet). National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ a b Rigotti, Nancy A; Tindle, Hilary A (2004). "The fallacy of 'light' cigarettes". BMJ. 328 (7440): E278–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7440.E278. PMC 2901853. PMID 15016715.

- ^ a b c d Kozlowski, L T; O'Connor, R J (2002). "Cigarette filter ventilation is a defective design because of misleading taste, bigger puffs, and blocked vents". Tobacco Control. 11: I40–50. doi:10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i40. PMC 1766061. PMID 11893814.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (11 November 2011). "Quitting smoking among adults--United States, 2001-2010". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 60 (44): 1513–1519. PMID 22071589.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Chaiton, Michael; Diemert, Lori; Cohen, Joanna E; Bondy, Susan J; Selby, Peter; Philipneri, Anne; Schwartz, Robert (2016). "Estimating the number of quit attempts it takes to quit smoking successfully in a longitudinal cohort of smokers". BMJ Open. 6 (6): e011045. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011045. PMC 4908897. PMID 27288378.

- ^ Gilpin, Elizabeth A; White, Martha M; Messer, Karen; Pierce, John P (2007). "Receptivity to Tobacco Advertising and Promotions Among Young Adolescents as a Predictor of Established Smoking in Young Adulthood". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (8): 1489–95. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.070359. PMC 1931446. PMID 17600271.

- ^ Laura Bach, "FLAVORED TOBACCO PRODUCTS ATTRACT KIDS", Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, (April. 2017)

- ^ a b Boseley, Sarah; Collyns, Dan; Lamb, Kate; Dhillon, Amrit (9 March 2018). "How children around the world are exposed to cigarette advertising". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ "Big Tobacco, Tiny Targets". Takeapart: Big Tobacco, Tiny Targets. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ A Counterblaste to Tobacco (retrieved February 22, 2008) Quote: A custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse.

- ^ Alston, Lee J.; Dupré, Ruth; Nonnenmacher, Tomas (2002). "Social reformers and regulation: the prohibition of cigarettes in the United States and Canada" (PDF). Explorations in Economic History. 39 (4): 425–445.

- ^ Gately, Iain (2001). Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-8021-3960-4.

- ^ Cutler, Abigail. "The Ashtray of History", The Atlantic Monthly, January/February 2007.

- ^ a b c More About Tobacco Advertising and the Tobacco Collections. Scriptorium.lib.duke.edu.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Alston, Lee J.; Dupré, Ruth; Nonnenmacher, Tomas (2002). "Social reformers and regulation: the prohibition of cigarettes in the United States and Canada" (PDF). Explorations in Economic History. 39 (4): 425–445.

- ^ a b Bonsack's cigarette machine Archived 2006-11-13 at the Wayback Machine. URL last accessed 2006-10-11.

- ^ a b c d James, Randy (15 June 2009). "A Brief History Of Cigarette Advertising". TIME. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ U.S. patent 238,640, with diagrams. URL last accessed 2006-10-11.

- ^ U.S. patent 247,795, with diagrams. URL last accessed 2006-10-11

- ^ Bennett, W.: The Cigarette Century[permanent dead link], Science 80, September/October 1980. URL last accessed 2006-10-11.

- ^ a b c d e f "The anti-tobacco reform and the temperance movement in Australia: connections and differences. - Free Online Library". Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images.php?token2=fm_st232.php&token1=fm_img6772.php&theme_file=fm_mt001.php&theme_name=Doctors%20Smoking&subtheme_name=Hospitalized%20Patients

- ^ Donald G. Gifford (2010) Suing the Tobacco and Lead Pigment Industries, p.15 quotation:

...during the early twentieth century, tobacco manufacturers virtually created the modern advertising and marketing industry as it is known today.

- ^ Stanton Glantz in Mad Men Season 3 Extra – Clearing the Air – The History of Cigarette Advertising, part 1, min 3:38 quotation:

...development of modern advertising. And it was really the tobacco industry, from the beginning, that was at the forefront of the development of modern, innovative, advertising techniques.

- ^ a b c Markel, Howard (20 March 2007). "Tracing the Cigarette's Path From Sexy to Deadly". The New York Times.

- ^ "Process of Treating Cigarette Tobacco". United States Patent Office.

- ^ a b Statement: Surgeon General's Report on Women and Tobacco Underscores Need for Congress to Grant FDA Authority Over Tobacco (Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids). Tobaccofreekids.org.

- ^ "Targeting women: Mass marketing begins, Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising". Retrieved 19 May 2018.

As the threat of tobacco prohibition from temperance unions settled down in the late 1920s, tobacco companies became bolder with their approach to targeting women through advertisements, openly targeting women in an attempt to broaden their market and increase sales. The late 1920s saw the beginnings of major mass marketing campaigns designed specifically to target women. Cigarette manufacturers have for a long time subtly suggested in some of their advertising that women smoked, a New York Times article from 1927 reveals. But Chesterfield s 1927 Blow some my way campaign was transparent to the public even at the time of printing, and soon after, the campaigns became less and less subtle. In 1928, Lucky Strike introduced its Cream of the Crop campaign, featuring celebrity testimonials from female smokers, and then followed with Reach for a Lucky Instead of a Sweet in 1929, designed to prey on female insecurities about weight and diet. As the decade turned, many cigarette brands came out of the woodwork and joined in on unabashedly targeting women by illustrating women smoking, rather than hinting at it.

- ^ "Targeting women:Let's Smoke Girls, Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising". Retrieved 19 May 2018.

Before the First World War, smoking was associated with the loose morals of prostitutes and wayward women. Clever marketers managed to turn this around in the 1920s and 1930s, latching onto women s liberation movements and transforming cigarettes into symbols of women's independence. In 1929, as part of this effort, the American Tobacco Company organized marches of women carrying Torches of Freedom (i.e., cigarettes) down New York s 5th Avenue to emphasize their emancipation. The tobacco industry also sponsored training sessions to teach women how to smoke, and competitions for most delicate smoker. Many of the advertisements targeting women throughout the decades have concentrated on women s empowerment. Early examples include I wish I were a man so I could smoke (Velvet, 1912), while later examples like You ve come a long way baby (Virginia Slims) were more clearly exploitive of the Women s Liberation Movement. It is interesting to note that the Marlboro brand, famous for its macho Marlboro Man, was for decades a woman s cigarette (Mild as May with Ivory tips to protect the lips) before it underwent an abrupt sex change in 1954. Only 5 percent of American women smoked in 1923 versus 12 percent in 1932 and 33 percent in 1965 (the peak year). Lung cancer was still a rare disease for women in the 1950s, though by the year 2000 it was killing nearly 70,000 women per year. Cancer of the lung surpassed breast cancer as the leading cause of cancer death among women in 1987.

- ^ Brandt, Allan M. (2007). The Cigarette Century. New York: Basic Books, pp. 84-85.

- ^ Robert N. Proctor, The Nazi War on Cancer, pp. 234–237.

- ^ Thomas D. Grant, Stormtroopers and Crisis in the Nazi Movement, p. 102.

- ^ Joyce Goodman and Jane Martin, Gender, Colonialism and Education, p. 81.

- ^ https://quoteinvestigator.com/2012/09/19/easy-quit-smoking/

- ^ a b Rolleston, J. D (1932). "The Cigarette Habit". Addiction. 30 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1932.tb04849.x. OCLC 79886767.

- ^ a b c d e f g Proctor, Robert N. (1 February 2001). "Commentary: Schairer and Schöniger's forgotten tobacco epidemiology and the Nazi quest for racial purity". International Journal of Epidemiology. 30 (1): 31–34. doi:10.1093/ije/30.1.31. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ Vernellia R. Randall (31 August 1999). "The History of Tobacco". Academic.udayton.edu. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Zigarettenwerbung in Deutschland – Marketing für ein gesundheitsgefährdendes Produkt (PDF). Rote Reihe: Tabakprävention und Tabakkontrolle. Heidelberg: Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum. 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ Dr. Annette Bornhäuser; Dr. med. Martina Pötschke-Langer (2001). Factsheet Tabakwerbeverbot (PDF). Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum. Retrieved 1 May 2016.