Jewish religious clothing: Difference between revisions

→top: add wikilinks; citation template; minor copyediting |

group together historically male garments; clarify tekhelet; consolidate refs |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Jewish religious clothing''' has been influenced by [[Mitzvah|Biblical commandments]], [[Tzniut|modesty requirements]] and the contemporary style of clothing worn in the many societies in which [[Jews]] have lived. In [[Judaism]], clothes are also a vehicle for religious ritual.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.haaretz.com/weekend/.premium-1.557028 |title=When a Tel Aviv fashion house meets Women of the Wall |work=[[Haaretz]] |first=Shachar |last=Atwan |date=November 8, 2013}}</ref> |

'''Jewish religious clothing''' has been influenced by [[Mitzvah|Biblical commandments]], [[Tzniut|modesty requirements]] and the contemporary style of clothing worn in the many societies in which [[Jews]] have lived. In [[Judaism]], clothes are also a vehicle for religious ritual.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.haaretz.com/weekend/.premium-1.557028 |title=When a Tel Aviv fashion house meets Women of the Wall |work=[[Haaretz]] |first=Shachar |last=Atwan |date=November 8, 2013}}</ref> |

||

==Men's clothing== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Many Jewish men historically wore [[turban]]s, [[tunic]]s, [[cloak]]s, and [[sandal]]s. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The ''[[tallit]]'' is a Jewish prayer shawl worn while reciting morning prayers as well as in the synagogue on Sabbath and holidays. In [[Yemen]], the wearing of such garments was not unique to prayer time alone, but was worn the entire day.<ref>Yehuda Ratzaby, ''Ancient Customs of the Yemenite Jewish Community'' (ed. Shalom Seri and [[Israel Kessar]]), Tel-Aviv 2005, p. 30 (Hebrew)</ref> The ''tallit'' has special twined and knotted fringes known as ''tzitzit'' attached to its four corners. It is sometimes referred to as |

||

| ⚫ | The ''[[tallit]]'' is a Jewish prayer shawl worn while reciting morning prayers as well as in the synagogue on Sabbath and holidays. In [[Yemen]], the wearing of such garments was not unique to prayer time alone, but was worn the entire day.<ref>Yehuda Ratzaby, ''Ancient Customs of the Yemenite Jewish Community'' (ed. Shalom Seri and [[Israel Kessar]]), Tel-Aviv 2005, p. 30 (Hebrew)</ref> The ''tallit'' has special twined and knotted fringes known as ''[[tzitzit]]'' attached to its four corners. It is sometimes referred to as ''arba kanfot'' (lit. 'four corners') although the term is more common for a ''tallit katan'', an undergarment with ''tzitzit''. According to the Biblical commandments, ''tzitzit'' must be attached to any four-cornered garment, and a thread with a blue dye known as ''[[tekhelet]]'' is supposed to be included in the ''tzitzit''. Since they are considered by Orthodox tradition to be a time-bound commandment, they are worn only by men; Conservative Judaism regards women as exempt from wearing ''tzitzit'', not as prohibited.<ref>[http://www.jewfaq.org/signs.htm Signs and Symbols]</ref> Jewish men are buried in a ''tallit'' as part of the [[tachrichim]] (shroud; burial garments). |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | A [[kippah]] or yarmulke (also called a kappel or |

||

| ⚫ | A ''[[kippah]]'' or ''yarmulke'' (also called a ''kappel'' or ''skull cap'') is a thin, slightly-rounded [[skullcap]] traditionally worn at all times by Orthodox Jewish men, and sometimes by both men and women in Conservative and Reform communities. Its use is associated with demonstrating respect and reverence for God.<ref>[http://judaism.about.com/od/prayersworshiprituals/f/kippah.htm Kippah]</ref> Jews in [[Arab lands]] did not traditionally wear yarmulkes, but rather larger rounded hats, without brims. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | A ''[[kittel]]'' ({{lang-yi|קיטל}}) is a white, knee-length, cotton robe worn by Jewish prayer leaders and some Orthodox Jews on the [[High Holidays]]. In some families, the head of the household wears a kittel at the [[Passover]] [[seder]].<ref>{{cite book |last=Eider |first=Shimon |authorlink=Shimon Eider |title=Halachos of Pesach |publisher=Feldheim publishers |isbn=0-87306-864-5}}</ref> In some circles it is customary for the groom at a [[Jewish wedding]] to wear a kittel under the wedding canopy. |

||

==Women's clothing== |

==Women's clothing== |

||

| Line 22: | Line 29: | ||

Married Orthodox Jewish women wear a scarf ([[tichel]]), a [[snood (headgear)|snood]], a hat, a beret, or - sometimes - a wig ([[sheitel]]) in order to conform with the requirement of [[halakha|Jewish religious law]] that married women [[Tzniut#Hair covering|cover their hair]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://canopycanopycanopy.com/10/she_goes_covered |title=She goes covered |first=Julia |last=Sherman |date=November 17, 2010}}</ref> |

Married Orthodox Jewish women wear a scarf ([[tichel]]), a [[snood (headgear)|snood]], a hat, a beret, or - sometimes - a wig ([[sheitel]]) in order to conform with the requirement of [[halakha|Jewish religious law]] that married women [[Tzniut#Hair covering|cover their hair]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://canopycanopycanopy.com/10/she_goes_covered |title=She goes covered |first=Julia |last=Sherman |date=November 17, 2010}}</ref> |

||

There are non-canonical rabbinical writings on hair covering in relation to ''[[tzniut]]'' (meaning |

There are non-canonical rabbinical writings on hair covering in relation to ''[[tzniut]]'' (meaning 'modesty'), such as: [[Shulchan Aruch]], Rabbi [[Jacob ben Asher]]'s [[Even Ha'ezer|Stone of Help]] 115, 4; [[Orach Chayim]] 75,2; Even Ha'ezer 21, 2 4.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.jofa.org/sites/default/files/uploaded_files/10002_u/01011.pdf|title="The Obligation of Married Women to Cover Their Hair"|last=Schiller|first=Mayer|date=1995|website=The Journal of Halacha|pages=81–108|access-date=June 26, 2016|edition=30}}</ref> |

||

Jewish women were distinguished from others in the western regions of the Roman Empire by their custom of veiling in public. The custom of veiling was shared by Jews with others in the eastern regions.<ref>{{cite book|author=Shaye J. D. Cohen|title=The Beginnings of Jewishness: Boundaries, Varieties, Uncertainties|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qbAwDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA31|date=17 January 2001|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-22693-7|pages=31–}}</ref> The custom petered out among Roman women but was retained by Jewish women as a sign of their identification as Jewesses. The custom has been retained among Orthodox women.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Judith Lynn Sebesta|author2=Larissa Bonfante|title=The World of Roman Costume|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GxGPLju4KEkC&pg=PA188|year=2001|publisher=Univ of Wisconsin Press|isbn=978-0-299-13854-7|pages=188–}}</ref> Jewish women also wore shawls or other head coverings at the time of the New Testament, keeping their hair long.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Dorothy Kelley Patterson|author2=Rhonda Harrington Kelley|title=Women's Evangelical Commentary: New Testament|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RHPMMSrLBZIC|date=June 2011|publisher=B&H Publishing Group|isbn=978-0-8054-9567-6|page=2}}</ref> Evidence drawn from the Talmud shows that pious Jewish women would wear shawls over their heads when they would leave their homes, but there was no practice of full facial coverings.<ref>{{cite book|author=James B. Hurley|title=Man and Woman in Biblical Perspective|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wHtKAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA270|date=3 July 2002|publisher=Wipf and Stock Publishers|isbn=978-1-57910-284-5|pages=270–}}</ref> In the medieval era Jewish women started veiling their faces under the influence of the Islamic societies they lived in.<ref>{{cite book|author=Mary Ellen Snodgrass|title=World Clothing and Fashion: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Social Influence|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gO9nBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA337|date=17 March 2015|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-317-45167-9|pages=337–}}</ref> In some Muslim regions such as in Baghdad Jewish women veiled their faces until the third decade of the twentieth century. In the more lax Kurdish regions, Jewish women did not cover their face.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VxEJrEY22egC&pg=PA212|title=The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times|author1=Reeva Spector Simon|first=|author2=[[Michael Laskier]]|author3=Sara Reguer|date=8 March 2003|publisher=Columbia University Press|year=|isbn=978-0-231-50759-2|location=|pages=212–}}</ref> |

Jewish women were distinguished from others in the western regions of the Roman Empire by their custom of veiling in public. The custom of veiling was shared by Jews with others in the eastern regions.<ref>{{cite book|author=Shaye J. D. Cohen|title=The Beginnings of Jewishness: Boundaries, Varieties, Uncertainties|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qbAwDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA31|date=17 January 2001|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-22693-7|pages=31–}}</ref> The custom petered out among Roman women but was retained by Jewish women as a sign of their identification as Jewesses. The custom has been retained among Orthodox women.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Judith Lynn Sebesta|author2=Larissa Bonfante|title=The World of Roman Costume|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GxGPLju4KEkC&pg=PA188|year=2001|publisher=Univ of Wisconsin Press|isbn=978-0-299-13854-7|pages=188–}}</ref> Jewish women also wore shawls or other head coverings at the time of the New Testament, keeping their hair long.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Dorothy Kelley Patterson|author2=Rhonda Harrington Kelley|title=Women's Evangelical Commentary: New Testament|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RHPMMSrLBZIC|date=June 2011|publisher=B&H Publishing Group|isbn=978-0-8054-9567-6|page=2}}</ref> Evidence drawn from the Talmud shows that pious Jewish women would wear shawls over their heads when they would leave their homes, but there was no practice of full facial coverings.<ref>{{cite book|author=James B. Hurley|title=Man and Woman in Biblical Perspective|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wHtKAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA270|date=3 July 2002|publisher=Wipf and Stock Publishers|isbn=978-1-57910-284-5|pages=270–}}</ref> In the medieval era Jewish women started veiling their faces under the influence of the Islamic societies they lived in.<ref>{{cite book|author=Mary Ellen Snodgrass|title=World Clothing and Fashion: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Social Influence|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gO9nBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA337|date=17 March 2015|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-317-45167-9|pages=337–}}</ref> In some Muslim regions such as in Baghdad Jewish women veiled their faces until the third decade of the twentieth century. In the more lax Kurdish regions, Jewish women did not cover their face.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VxEJrEY22egC&pg=PA212|title=The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times|author1=Reeva Spector Simon|first=|author2=[[Michael Laskier]]|author3=Sara Reguer|date=8 March 2003|publisher=Columbia University Press|year=|isbn=978-0-231-50759-2|location=|pages=212–}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | A [[kittel]] ( |

||

==Jewish customs vs. Gentile customs== |

==Jewish customs vs. Gentile customs== |

||

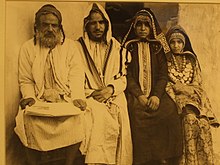

[[File:Meysha Abyadh, Jewish silversmith.jpg|thumb|top|Traditional Jewish attire in Yemen]] |

[[File:Meysha Abyadh, Jewish silversmith.jpg|thumb|top|Traditional Jewish attire in Yemen]] |

||

A question was posed to Rabbi [[Joseph Colon Trabotto|Joseph Colon]] (Maharik) regarding "Gentile clothing" and whether or not a Jew who wears such clothing transgresses a biblical prohibition that states, "You shall not walk in their precepts" ({{bibleverse||Leviticus|18:3|JP}}). In a protracted ''responsum'', <ref>Questions & Responsa of Rabbi Joseph Colon, ''responsum'' # 88</ref> Rabbi Colon wrote that any Jew who might be a practising physician is permitted to wear a physician's cape (traditionally worn by Gentile physicians on account of their expertise in that particular field of science and their wanting to be recognized as such), and that the Jewish physician who wore it has not infringed upon any law in the Torah, even though Jews were not wont to wear such garments in former times. He noted that there is nothing attributed to "superstitious" practice by their wearing such a garment, while, at the same time, there isn't anything promiscuous or immodest about wearing such a cape, neither is it worn out of haughtiness. Moreover, he has understood from [[Maimonides]] (''Hil. Avodat Kokhavim'' 11:1) that there is no commandment requiring a fellow Jew to seek out and look for clothing which would make them stand out as "different" from what is worn by Gentiles, but rather, only to make sure that what a Jew might wear is not an "exclusive" Gentile item of clothing. He noted that wearing a physician's cape is not an exclusive Gentile custom, noting, moreover, that since the custom to wear the cape varies from place to place, and that, in France, physicians do not have it as a custom to wear such capes, it cannot therefore be an exclusive Gentile custom.<ref |

A question was posed to Rabbi [[Joseph Colon Trabotto|Joseph Colon]] (Maharik) regarding "Gentile clothing" and whether or not a Jew who wears such clothing transgresses a biblical prohibition that states, "You shall not walk in their precepts" ({{bibleverse||Leviticus|18:3|JP}}). In a protracted ''responsum'', <ref name="Colon88">Questions & Responsa of Rabbi Joseph Colon, ''responsum'' # 88</ref> Rabbi Colon wrote that any Jew who might be a practising physician is permitted to wear a physician's cape (traditionally worn by Gentile physicians on account of their expertise in that particular field of science and their wanting to be recognized as such), and that the Jewish physician who wore it has not infringed upon any law in the Torah, even though Jews were not wont to wear such garments in former times. He noted that there is nothing attributed to "superstitious" practice by their wearing such a garment, while, at the same time, there isn't anything promiscuous or immodest about wearing such a cape, neither is it worn out of haughtiness. Moreover, he has understood from [[Maimonides]] (''Hil. Avodat Kokhavim'' 11:1) that there is no commandment requiring a fellow Jew to seek out and look for clothing which would make them stand out as "different" from what is worn by Gentiles, but rather, only to make sure that what a Jew might wear is not an "exclusive" Gentile item of clothing. He noted that wearing a physician's cape is not an exclusive Gentile custom, noting, moreover, that since the custom to wear the cape varies from place to place, and that, in France, physicians do not have it as a custom to wear such capes, it cannot therefore be an exclusive Gentile custom.<ref name="Colon88"/> |

||

According to Rabbi Colon, modesty was still a criterion for wearing Gentile clothing, writing: "...even if Israel made it as their custom [to wear] a certain item of clothing, while the Gentiles [would wear] something different, if the Israelite garment should not measure up to [the standard established in] Judaism or of modesty more than what the Gentiles hold as their practice, there is no prohibition whatsoever for an Israelite to wear the garment that is practised among the Gentiles, seeing that it is in [keeping with] the way of fitness and modesty just as that of Israel."{{citation needed|date=March 2018}} |

According to Rabbi Colon, modesty was still a criterion for wearing Gentile clothing, writing: "...even if Israel made it as their custom [to wear] a certain item of clothing, while the Gentiles [would wear] something different, if the Israelite garment should not measure up to [the standard established in] Judaism or of modesty more than what the Gentiles hold as their practice, there is no prohibition whatsoever for an Israelite to wear the garment that is practised among the Gentiles, seeing that it is in [keeping with] the way of fitness and modesty just as that of Israel."{{citation needed|date=March 2018}} |

||

Revision as of 21:38, 20 July 2018

Jewish religious clothing has been influenced by Biblical commandments, modesty requirements and the contemporary style of clothing worn in the many societies in which Jews have lived. In Judaism, clothes are also a vehicle for religious ritual.[1]

Men's clothing

Many Jewish men historically wore turbans, tunics, cloaks, and sandals.

Tallit, tzitzit, and tallit katan

The tallit is a Jewish prayer shawl worn while reciting morning prayers as well as in the synagogue on Sabbath and holidays. In Yemen, the wearing of such garments was not unique to prayer time alone, but was worn the entire day.[2] The tallit has special twined and knotted fringes known as tzitzit attached to its four corners. It is sometimes referred to as arba kanfot (lit. 'four corners') although the term is more common for a tallit katan, an undergarment with tzitzit. According to the Biblical commandments, tzitzit must be attached to any four-cornered garment, and a thread with a blue dye known as tekhelet is supposed to be included in the tzitzit. Since they are considered by Orthodox tradition to be a time-bound commandment, they are worn only by men; Conservative Judaism regards women as exempt from wearing tzitzit, not as prohibited.[3] Jewish men are buried in a tallit as part of the tachrichim (shroud; burial garments).

Kippah

A kippah or yarmulke (also called a kappel or skull cap) is a thin, slightly-rounded skullcap traditionally worn at all times by Orthodox Jewish men, and sometimes by both men and women in Conservative and Reform communities. Its use is associated with demonstrating respect and reverence for God.[4] Jews in Arab lands did not traditionally wear yarmulkes, but rather larger rounded hats, without brims.

Kittel

A kittel (Yiddish: קיטל) is a white, knee-length, cotton robe worn by Jewish prayer leaders and some Orthodox Jews on the High Holidays. In some families, the head of the household wears a kittel at the Passover seder.[5] In some circles it is customary for the groom at a Jewish wedding to wear a kittel under the wedding canopy.

Women's clothing

Married Orthodox Jewish women wear a scarf (tichel), a snood, a hat, a beret, or - sometimes - a wig (sheitel) in order to conform with the requirement of Jewish religious law that married women cover their hair.[6]

There are non-canonical rabbinical writings on hair covering in relation to tzniut (meaning 'modesty'), such as: Shulchan Aruch, Rabbi Jacob ben Asher's Stone of Help 115, 4; Orach Chayim 75,2; Even Ha'ezer 21, 2 4.[7]

Jewish women were distinguished from others in the western regions of the Roman Empire by their custom of veiling in public. The custom of veiling was shared by Jews with others in the eastern regions.[8] The custom petered out among Roman women but was retained by Jewish women as a sign of their identification as Jewesses. The custom has been retained among Orthodox women.[9] Jewish women also wore shawls or other head coverings at the time of the New Testament, keeping their hair long.[10] Evidence drawn from the Talmud shows that pious Jewish women would wear shawls over their heads when they would leave their homes, but there was no practice of full facial coverings.[11] In the medieval era Jewish women started veiling their faces under the influence of the Islamic societies they lived in.[12] In some Muslim regions such as in Baghdad Jewish women veiled their faces until the third decade of the twentieth century. In the more lax Kurdish regions, Jewish women did not cover their face.[13]

Jewish customs vs. Gentile customs

A question was posed to Rabbi Joseph Colon (Maharik) regarding "Gentile clothing" and whether or not a Jew who wears such clothing transgresses a biblical prohibition that states, "You shall not walk in their precepts" (Leviticus 18:3). In a protracted responsum, [14] Rabbi Colon wrote that any Jew who might be a practising physician is permitted to wear a physician's cape (traditionally worn by Gentile physicians on account of their expertise in that particular field of science and their wanting to be recognized as such), and that the Jewish physician who wore it has not infringed upon any law in the Torah, even though Jews were not wont to wear such garments in former times. He noted that there is nothing attributed to "superstitious" practice by their wearing such a garment, while, at the same time, there isn't anything promiscuous or immodest about wearing such a cape, neither is it worn out of haughtiness. Moreover, he has understood from Maimonides (Hil. Avodat Kokhavim 11:1) that there is no commandment requiring a fellow Jew to seek out and look for clothing which would make them stand out as "different" from what is worn by Gentiles, but rather, only to make sure that what a Jew might wear is not an "exclusive" Gentile item of clothing. He noted that wearing a physician's cape is not an exclusive Gentile custom, noting, moreover, that since the custom to wear the cape varies from place to place, and that, in France, physicians do not have it as a custom to wear such capes, it cannot therefore be an exclusive Gentile custom.[14]

According to Rabbi Colon, modesty was still a criterion for wearing Gentile clothing, writing: "...even if Israel made it as their custom [to wear] a certain item of clothing, while the Gentiles [would wear] something different, if the Israelite garment should not measure up to [the standard established in] Judaism or of modesty more than what the Gentiles hold as their practice, there is no prohibition whatsoever for an Israelite to wear the garment that is practised among the Gentiles, seeing that it is in [keeping with] the way of fitness and modesty just as that of Israel."[citation needed]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Atwan, Shachar (November 8, 2013). "When a Tel Aviv fashion house meets Women of the Wall". Haaretz.

- ^ Yehuda Ratzaby, Ancient Customs of the Yemenite Jewish Community (ed. Shalom Seri and Israel Kessar), Tel-Aviv 2005, p. 30 (Hebrew)

- ^ Signs and Symbols

- ^ Kippah

- ^ Eider, Shimon. Halachos of Pesach. Feldheim publishers. ISBN 0-87306-864-5.

- ^ Sherman, Julia (November 17, 2010). "She goes covered".

- ^ Schiller, Mayer (1995). ""The Obligation of Married Women to Cover Their Hair"" (PDF). The Journal of Halacha (30 ed.). pp. 81–108. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ Shaye J. D. Cohen (17 January 2001). The Beginnings of Jewishness: Boundaries, Varieties, Uncertainties. University of California Press. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-0-520-22693-7.

- ^ Judith Lynn Sebesta; Larissa Bonfante (2001). The World of Roman Costume. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 188–. ISBN 978-0-299-13854-7.

- ^ Dorothy Kelley Patterson; Rhonda Harrington Kelley (June 2011). Women's Evangelical Commentary: New Testament. B&H Publishing Group. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8054-9567-6.

- ^ James B. Hurley (3 July 2002). Man and Woman in Biblical Perspective. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-1-57910-284-5.

- ^ Mary Ellen Snodgrass (17 March 2015). World Clothing and Fashion: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Social Influence. Routledge. pp. 337–. ISBN 978-1-317-45167-9.

- ^ Reeva Spector Simon; Michael Laskier; Sara Reguer (8 March 2003). The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times. Columbia University Press. pp. 212–. ISBN 978-0-231-50759-2.

- ^ a b Questions & Responsa of Rabbi Joseph Colon, responsum # 88

Further reading

- Rubens, Alfred, (1973) A History of Jewish Costume. ISBN 0-297-76593-0.

- Silverman, Eric. (2013) A Cultural History of Jewish Dress. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-84788-286-8.

External links

Media related to Jewish clothing at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jewish clothing at Wikimedia Commons