Knights of Columbus: Difference between revisions

→Charitable giving: ce trim opinion |

→Board and officers: trim undue detail for this article. Consider for sub-article linked |

||

| Line 444: | Line 444: | ||

The Supreme Council elects insurance members to serve three year terms on the 24 member Supreme [[Board of Directors]].<ref name=et/> It is led by five supreme officers: the [[Supreme Knight of the Knights of Columbus|Supreme Knight]], Deputy Supreme Knight, Supreme Secretary, Supreme Treasurer, Supreme Advocate, and Supreme Physician.{{sfn|Kauffman|1982|pp=375–376}}<ref name=et/> The salaries of supreme officers have drawn criticism as being excessive.<ref name=pay/><ref name=tablet9719/> Salaries are set by the board of directors and ratified by the delegates to the Supreme Convention.<Ref name=pay/> |

The Supreme Council elects insurance members to serve three year terms on the 24 member Supreme [[Board of Directors]].<ref name=et/> It is led by five supreme officers: the [[Supreme Knight of the Knights of Columbus|Supreme Knight]], Deputy Supreme Knight, Supreme Secretary, Supreme Treasurer, Supreme Advocate, and Supreme Physician.{{sfn|Kauffman|1982|pp=375–376}}<ref name=et/> The salaries of supreme officers have drawn criticism as being excessive.<ref name=pay/><ref name=tablet9719/> Salaries are set by the board of directors and ratified by the delegates to the Supreme Convention.<Ref name=pay/> |

||

{| class="wikitable" style="margin-left:1em" |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="background:#efefef" width=150px| Supreme Knight |

|||

!style="background:#efefef" width=200px| [[Carl A. Anderson]] |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="background:#efefef" | Supreme Chaplain |

|||

!style="background:#efefef" | [[William E. Lori|Archbishop William E. Lori]] |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="background:#efefef; font-size:smaller" | Deputy Supreme Knight |

|||

!style="background:#efefef; font-size:smaller" | [[Patrick E. Kelly]] |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="background:#efefef; font-size:smaller" | Supreme Secretary |

|||

!style="background:#efefef; font-size:smaller" | Michael O'Connor |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="background:#efefef; font-size:smaller" | Supreme Treasurer |

|||

!style="background:#efefef; font-size:smaller" | Ronald Schwarz |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="background:#efefef; font-size:smaller" | Supreme Advocate |

|||

!style="background:#efefef; font-size:smaller" | John Marrella |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="background:#efefef; font-size:smaller" | Supreme Warden |

|||

!style="background:#efefef; font-size:smaller" | Francis Drouhard |

|||

|- |

|||

!style="background:#efefef; font-size:smaller" | Supreme Master |

|||

!style="background:#efefef; font-size:smaller" | Dennis Stoddard |

|||

|} |

|||

====Supreme Convention==== |

====Supreme Convention==== |

||

Revision as of 15:29, 11 December 2019

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| The Knights of Columbus emblem consists of a shield mounted on a Formée cross. Mounted on the shield are a fasces, an anchor, and a dagger. Emblem of the Knights of Columbus | |

| Abbreviation | K of C |

|---|---|

| Formation | March 29, 1882 |

| Type | Catholic fraternal service organization |

| Headquarters | Knights of Columbus Building, New Haven, Connecticut, US |

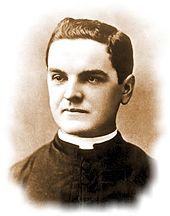

Founder | Michael J. McGivney |

Supreme Knight | Carl A. Anderson |

Supreme Chaplain | William E. Lori |

| Affiliations | |

| Website | www |

The Knights of Columbus is the world's largest Catholic fraternal service organization.[1][2] Founded in 1882 by Michael J. McGivney in New Haven, Connecticut, it was named in honor of Christopher Columbus. Originally serving as a mutual benefit society to working-class and immigrant Catholics in the United States, it developed into a fraternal benefit society dedicated to providing charitable services, including war and disaster relief, actively defending Catholicism in various nations, and promoting Catholic education.[1][3][4] The Knights also support the Catholic Church's positions on public policy issues, including various political causes, and are participants in the new evangelization. The current Supreme Knight is Carl A. Anderson.

As of 2019, there are nearly two million members around the world.[5][6][7] Membership is limited to practicing Catholic men aged 18 or older. The order consists of four different degrees, each exemplifying a different principle of the order.[1] The are more than 16,000 councils around the world,[6] including over 300 on college campuses.[8][9] The Knights' official junior organization is known as the Columbian Squires[10] and the order's patriotic arm is the Fourth Degree.[11]

From 2007 to 2017, charitable giving was more than $1.55 billion.[a] The organization also provides certain financial services to affiliated groups and individuals.[13] The Knights are also well known for their insurance program with more than 2 million insurance contracts, totaling more than US$100 billion of life insurance in force.[14] This is backed by $21 billion in assets as of 2014.[14] This places it on the Fortune 1000 list. The order also owns the Knights of Columbus Asset Advisors, a money management firm that invests in accordance with Catholic social teachings.

History

Early years

Michael J. McGivney, an Irish-American Catholic priest, founded the Knights of Columbus, with a group of men from St. Mary's Parish,[15][16] incorporating it on March 29, 1882.[17] Although its was initially based in Connecticut, it later expanded throughout the United States.[18]

The order was intended to be a mutual benefit society.[19][20] As a parish priest in an immigrant community, McGivney wanted to provide insurance to care for families who faced unforeseen hardship.[21] At that time, Roman Catholics were frequently excluded from labor unions, popular fraternal organizations, and other organized groups that provided such social services.[22][23]

The original insurance system devised by McGivney gave a deceased Knight's widow a $1,000 death benefit,[24] funded by a pro-rata contribution from the membership.[24][25] There was also a sick benefit for members who fell ill and could not work.[26]

The Fourth Degree was created in New York in 1990.[27] In 1903, the Board of Directors officially approved a new degree exemplifying patriotism Order-wide, using the New York City model.[28]

Early 20th century

The Knights supported the war effort in World War I by establishing soldiers' welfare centers in the US and abroad.[29][30] After the war, the Knights became involved in education, occupational training, and employment programs for the returning troops.[31]

After World War I, some Americans had concerns about the assimilation of immigrants; they wanted public schools to teach all children to be American. In 1922, the Oregon Compulsory Education Act disallowed parochial schools including Catholic schools in that state,[32][33] requiring almost all children in Oregon to attend public school after 1926.[34] The Knights of Columbus challenged the law in court,[35] in Pierce v. Society of Sisters, winning a ruling that the act was unconstitutional.[36]

In the 1920s there was growing anti-Semitism in the United States related to economic competition and the fears of social change from decades of changed immigration, a lingering anti-German sentiment left over from World War I, and anti-black violence erupted in numerous locations as well. To combat the animus targeted at racial and religious minorities, including Catholics, the order formed a historical commission which published a series of books on their contributions, among other activities. The "Knights of Columbus Racial Contributions Series" of books included three titles: The Gift of Black Folk, by W. E. B. Du Bois, The Jews in the Making of America by George Cohen, and The Germans in the Making of America by Frederick Schrader.[37]

During the nadir of American race relations, a bogus oath was circulated claiming that Fourth Degree Knights swore to exterminate Freemasons and Protestants.[38] The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), spread the bogus oath as part of their contemporary campaign against Catholics.[39][40][41] Numerous state councils and the Supreme Council believed publication would stop if the KKK were assessed fines or punished by jail time assessed and began suing distributors for libel.[42] As a result, the KKK ended its publication of the false oath. As the order did not wish to appear motivated by a "vengeful spirit", it asked for leniency from judges when sentencing offenders.[42]

Recent history

Today, according to Massimo Faggioli, the Knights of Columbus are "'an extreme version' of a post-Vatican II phenomenon, the rise of discrete lay groups that have become centers of power themselves."[12] As the order and its charitable works grew, so did its prominence within the church.[43] Pope John Paul II referred to the order as the "strong right arm of the Church" for their support of the church, as well as for their philanthropic and charitable efforts.[44]

Degrees and principles

The order is dedicated to the principles of charity, unity, fraternity, and patriotism.[45] The first ritual handbook, printed in 1885, contained only sections teaching unity and charity. The third section, espousing fraternity, was adopted in 1891.[46]

The Fourth Degree, which is dedicated to patriotism, was adopted in 1903.[47][48] Members of the Fourth Degree join assemblies which are separate from ordinary councils.[47] Assemblies may form color guards, which are often the most visible arm of the Knights.[49] They often attend important civic and church events.[49]

Charitable giving

| Year | US dollars donated | Volunteer hours donated |

|---|---|---|

| 2018[6][7][45][50][51][52] | $185,000,000+ | 76,000,000+ |

| 2017[b] | ||

| 2015[12][9] | $175,000,000+ | 73,500,000+ |

| 2013[c] | ||

| 2012[54] | $167,549,817 | 70,113,207 |

| 2011[55] | $158,000,000 | 70,053,000 |

| 2010[56][d] | $155,000,000 | 70,049,000 |

| 2009[58] | $151,000,000 | 69,252,000 |

| 2008[59] | $150,000,000 | 68,784,000 |

| 2001[60] | $110,000,000 | |

| 1995[61] | $105,000,000 | 50,000,000 |

| 1982[62][e] | $41,700,000 | 10,400,000 |

| 1984[63] | $52,000,000 | 13,400,000 |

| 1980[64] | $32,000,000 | 9,000,000 |

Beginning in 1897, the National Council encouraged local councils to establish charity funds to support members affected by the 1890s depression.[65] A number of donations were made following a series of natural and man-made disasters in the early 20th century in the United States and around the world, including $100,000 for the 1906 San Francisco earthquake relief efforts.[66][67]

Many councils operated as social welfare agencies during the early 20th century, working as employment agencies and providing aid to the poor and sick.[68][69] During the late 20th century, those with intellectual disabilities became a special priority.[48]

In 2018, the order gave more than $185 million directly to charity and performed over 76 million man hours in volunteer service.[50][45][7][6][51][52] Much of the recent financial effort went to initiatives of the Vatican and the US bishops.[12] According to one commentator in 2018, "there is hardly a corner of the Catholic world where the resources of this international force have not left an impression."[12]

Insurance program

Early years

| Year | Insurance in force | Assets |

|---|---|---|

| 1957[70] | $690,000,000 | $124,000,000 |

| 1956[71][f] | $650,000,000 | |

| 1955[71] | $562,000,000 | |

| 1953[70] | $420,000,000 | |

| 1932[67] | ~$300,000,000 | |

| 1919[72] | $140,000,000 | |

| 1897[73] | $42,282 | |

| 1896[74] | $12,000 |

The original insurance system devised by McGivney gave a deceased Knight's widow a $1,000 death benefit. Each member was assessed $1 upon a death, and when the number of Knights grew beyond 1,000, the assessment decreased according to the rate of increase.[24] Each member, regardless of age, was assessed equally. As a result, younger, healthier members could expect to pay more over the course of their lifetimes than those men who joined when they were older.[25]

There was also a Sick Benefit Deposit for members who fell ill and could not work. Each sick Knight was entitled to draw up to $5 a week for 13 weeks (roughly equivalent to $125.75 in 2009 dollars).[75] If he remained sick after that, the council to which he belonged determined the sum of money given to him.[26]

In the post-World War II era, to enhance yields on its capital, the organization began investing in real estate leaseback transactions.[76] Between 1952 and 1962, 18 pieces of land were purchased for a total of $29 million.[77] Late in 1953 the order purchased the land beneath Yankee Stadium for $2.5 million.[77] In 1971, the City of New York took the land by eminent domain.[78]

Modern program

| Year | Insurance in force (billions) |

Assets (billions) |

|---|---|---|

| 2019[79][50][52] | $109+ | $26+ |

| 2018[80] | $109 | $26 |

| 2015[12][81] | $99 | |

| 2014[82] | $100 | $24 |

| 2013[83][84] | $90 | $19.8 |

| 2012[85] | $88.4 | $19.4 |

| 2011[86][87] | $83.5 | $18.0 |

| 2010[88] | $79.0 | $16.9 |

| 2009[88] | $74.3 | $15.5 |

| 2008[88][89] | $70.0 | $14 |

| 2007[88][23] | $66.0 | $13 |

| 2006[88][90] | $61.9 | $12.2 |

| 2005[88] | $57.7 | |

| 2004[88] | $53.3 | |

| 2003[88] | $49.1 | |

| 2002[88] | $45.6 | |

| 2001[88] | $42.9 | |

| 2000[88][83] | $40.4 | |

| 1999[88] | $38 | |

| 1997[61] | $30 | |

| 1992[91] | $20 | |

| 1990[92] | $14 | $3.6 |

| 1981[93] | $6.4 | $1 |

| 1976[93] | $3.6 | $656 million |

| 1975[94] | $3 | |

| 1971[94] | $2 | |

| 1964[95] | $1+ | |

| 1960[94] | $1 |

The order offers permanent and term life insurance, as well as annuities, long term care insurance, and disability insurance.[83][87][81] The order has more than $109 billion of life insurance policies in force and $26 billion in assets as of 2019.[79][50][52] A. M. Best ranked it 49th on the list of all life insurance companies in North America.[89]

The order chooses equities that first are a sound investment and also do not conflict with its view of Catholic social teaching.[13] and calls itself "champions of ethical investing."[12] Its insurance operation invests in loans to various Catholic institutions.[96][77][g] As of 2008[update], over $500 million had been loaned through the ChurchLoan program.[96]

For 40 consecutive years, the order has received A. M. Best's highest rating, A++.[97][83][52] A 2017 lawsuit claimed the Knights were inflating their membership numbers to improve their rankings.[98]

Organization

| Year | Membership | Councils |

|---|---|---|

| 2018[99][100] | 1,967,585 | 15,900 |

| 2013[53][84] | 1,843,587 | 14,606 |

| 2001[60] | 1,600,000 | 11,500 |

| 1995[61] | 1,600,000 | |

| 1990[92] | 1,500,000 | |

| 1984[63] | 1,400,000 | 8,000 |

| 1981[101][102][h] | 1,350,000 | <7,000 |

| 1977[102] | 1,230,000 | |

| 1964[95] | 1,000,000+ | |

| 1957[70] | 1,000,000 | |

| 1938[103] | 500,000 | |

| 1932[67] | 600,000 | 2,500+ |

| 1931[69] | 2,600 | |

| 1923[104] | 774,189 | 2,290 |

| 1920[72] | 581,983 | 1,937 |

| 1917[105] | 400,000 | |

| 1914[106] | 300,000+ | |

| 1909[107] | 230,000 | 1300 |

| 1899[106][107] | 40,267[i] | 300 |

| 1897[65][73] | 16,651 | 195 |

| 1896[73] | 13,694 | |

| 1892[109] | 6,500 | |

| 1886[65] | 2,700 | 27 |

| 1884[110] | 459 | 5 |

Members must be at least 18 years old, Catholic, and male.[50] As of 2015[update] there were 1,918,122 knights. Each member belongs to one of more than 16,000 local "councils" around the world.[6][111] Members are admitted in Mexico, the Philippines, Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, South Korea, several Caribbean countries, the United States, and Canada, although insurance is not not sold to members in every country.

In 1969, the Knights opened a 321', 23 story headquarters building in New Haven.[112][23] At the time, it was the tallest building in the city.[112]

Supreme Council

The Supreme Council is the governing body of the order and is composed of elected representatives from each geographical jurisdiction.

Board and officers

The Supreme Council elects insurance members to serve three year terms on the 24 member Supreme Board of Directors.[84] It is led by five supreme officers: the Supreme Knight, Deputy Supreme Knight, Supreme Secretary, Supreme Treasurer, Supreme Advocate, and Supreme Physician.[113][84] The salaries of supreme officers have drawn criticism as being excessive.[91][114] Salaries are set by the board of directors and ratified by the delegates to the Supreme Convention.[91]

Supreme Convention

The Knights of Columbus invites the head of state of every country in which they operate to the annual Supreme Convention.[115] United States presidents who have attended include Richard Nixon,[116] Ronald Reagan,[117] George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush.[118][119] Others, including Bill Clinton[119] and Barack Obama,[118] sent written messages.

College councils

The college councils program started with the chartering of University of Notre Dame Council #1477 in 1910.[120]As of 2018, there over 300 college councils.[8][9]

Promotion of the Catholic faith

Anti-religious discrimination efforts

Since its earliest days, the Knights of Columbus has been a "Catholic anti-defamation society."[121] In 1914, it established a Commission on Religious Prejudices.[121]

As part of the effort, the order distributed pamphlets, and lecturers toured the country speaking on how Catholics could love and be loyal to America.[122]

Evangelism

Since its founding, the Knights of Columbus has been involved in evangelism. The creation of the 4th Degree, with its emphasis on patriotism, performed an anti-defamation function as well as asserting claims to Americanism.[123][124] In response to a defamatory "bogus oath" circulated by the KKK,[125] in 1914 the Knights set up a framework for a lecture series and educational programs to combat anti-Catholic sentiment.[126]

In 1948, the Knights started the Catholic Information Service (CIS) to provide low-cost Catholic publications for the general public as well as for parishes, schools, retreat houses, military installations, correctional facilities, legislatures, the medical community, and for individuals who request them.[127][128] Since then, CIS has printed millions of booklets, and thousands of people have enrolled in CIS correspondence and on-line courses.[128]

Political activity

While the Knights were active politically from an early date, in the years following the Second Vatican Council, as the "Catholic anti-defamation character" of the order began to diminish as Catholics became more accepted, the leadership "attempted to stimulate the membership to a greater awareness of the religious and moral issues confronting the Church."[12] That led to the creation of a "variety of new programs reflecting the proliferation of the new social ministries of the church."[18][12]

The leadership of the order has been, at times, both liberal and conservative. Martin H. Carmody and Luke E. Hart were both political conservatives, but John J. Phelan was a Democratic politician prior to becoming Supreme Knight,[129] John Swift's "strong support for economic democracy and social-welfare legislation marks him as a fairly representative New Deal anti-communist,"[130] and Francis P. Matthews was a civil rights official and member of Harry Truman's cabinet. The current Supreme Knight, Carl A. Anderson, previously served in Ronald Reagan's White House.

While the Knights of Columbus support political awareness and activity, United States councils are prohibited by tax laws from engaging in candidate endorsement and partisan political activity due to their non-profit status.[131] The rules of the order also prohibit partisan politics in council chambers or at any events.[132] Public policy activity is limited to issue-specific campaigns, typically dealing with Catholic family and Sanctity of Life issues.[133][50] They state that

In addition to performing charitable works, the Knights of Columbus encourages its members to meet their responsibilities as Catholic citizens and to become active in the political life of their local communities, to vote and to speak out on the public issues of the day. ... In the political realm, this means opening our public policy efforts and deliberations to the life of Christ and the teachings of the Church. In accord with our Bishops, the Knights of Columbus has consistently maintained positions that take these concerns into account. The order supports and promotes the social doctrine of the Church, including a robust vision of religious liberty that embraces religion's proper role in the private and public spheres.[133]

The order opposed persecution of Catholics in Mexico during the Cristero War,[134] and opposed communism.[135][136] They have also advocated for a culture of life,[137][45][50] for defining marriage as the union of one man and one woman,[138][50] in defense of religious liberty,[51] and for promoting faithful citizenship.[139][50]

During the 20th century, the order established the Commission on Religious Prejudices, and the Knights of Columbus Historical Commission which combated racism.[140] It was also supportive of trade unionism, and published the works "of the broad array of intellectuals," including George Schuster, Samuel Flagg Bemis, Allan Nevins, and W. E. B. DuBois.[140] During the Cold War, the order had a history of anti-socialist, anti-communist crusades.[141] They lobbied to add "under God" to the Pledge of Allegiance, as a religious response to Soviet atheism.[142][143] According to Christopher J. Kauffman, "If the Knights displayed a conservative tenor, it was not political conservatism but rather cultural conservatism."[130]

Subsidiaries

Museum

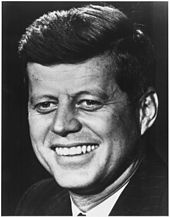

On March 10, 2001, the order opened a museum in New Haven dedicated to their history.[60][23] The 77,000 square foot building cost $10 million to renovate.[60] It holds mosaics on loan from the Vatican and gifts from Popes, the membership application from John F. Kennedy, and a number of other items related to the history of the Knights.[60] Near the entrance is the cross held by Jesus Christ on the facade of St. Peter's Basilica[60] before undergoing a Knights-financed renovation.[144] As many as 300,000 visitors were expected per year.[60]

Knights of Columbus Asset Advisors

In 2015, the order launched Knights of Columbus Asset Advisors, a money management firm that invests money in accordance with Catholic social teaching.[13][81] The firm uses the Socially Responsible Investment Guidelines published by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops to guide their investment decisions.[13][81] The guidelines include protecting human life, promoting human dignity, reducing arms production, pursuing economic justice, protecting the environment, and encouraging corporate responsibility.[j] The goal, according to Anthony V. Minopoli, chief investment officer of the Knights of Columbus and president and chief investment officer of Knights of Columbus Asset Advisors, is to "partner with Catholic investors and provide them with what we've been providing Knights of Columbus for years."[13]

The firm began with $21.4 billion in assets under management, all of which came from the Knights of Columbus.[13] Their initial goal was to capture 2.5 to 3 percent of the $150-billion Catholic market in the first three to five years.[13][81] They began with six mutual funds, two made up of bonds and four of stocks, with a $200-million total investment from the Knights of Columbus.[13][81] The funds (limited-duration bond and core bond, and large-cap growth, large-cap value, small-cap core, and international equity) are targeted towards institutional investors, but individuals can also invest if they meet the minimum amount invested.[13] As of 2019[update], the assets under management totaled more than $24 billion.[146]

In addition to the wholly owned subsidiary, it also purchased 20 percent of Boston Advisors, a boutique investment management firm, managing assets for institutional and high-net-worth investors.[13][146] Knights of Columbus Asset Advisors manages the fixed-income strategies for their funds while Boston Advisors subadvises on the equity strategies.[13][146] Knights of Columbus Asset Advisors also offers model portfolio, outsourced CIO services, a bank loan strategy, and other alternative investment strategies.[13] In 2019, the Knights purchased the institutional management business of Boston Advisors.[146]

Saint John Paul II National Shrine

The order owns and operates the Saint John Paul II National Shrine in Washington D.C.[12] In 2011, the Order purchased the 130,000-square-foot John Paul II Cultural Center.[147][148][12] The mission as a cultural center ended in 2009[149] and the Knights rebranded it as a shrine to Pope John Paul II.[147][148] Soon after the pope was canonized, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops named the building a national shrine.[149]

Each year 64,000 pilgrims visit the shrine, which features video content, interactive displays, and personal effects from John Paul.[149] There is also a first class relic of the pope's blood on display for veneration.[149] It also serves as a base for the Order in Washington, D.C.[150]

Notable Knights

Many notable Catholic men from all over the world have been Knights of Columbus. In the United States, some of the most notable include John F. Kennedy; Ted Kennedy;,[152] Vince Lombardi, Al Smith;[153] Sargent Shriver;[154] Samuel Alito; John Boehner;[155] Ray Flynn;[156] Jeb Bush;[157] and Sergeant Major Daniel Daly,[158] a two-time Medal of Honor recipient.[159]

In the world of sports, Vince Lombardi, the famed former coach of the Green Bay Packers;[160] James Connolly, the first Olympic gold-medal champion in modern times;[161] Floyd Patterson, former heavyweight boxing champion;[162] and baseball legend Babe Ruth[163] were all knights.

On October 15, 2006, Bishop Rafael Guizar Valencia (1878–1938) was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI in Rome. In 2000, six other Knights, known as the Mexican martyrs who were killed during the repression following the 1920s revolution, were declared saints by Pope John Paul II.[164]

Emblem of the order

The emblem of the order was designed by Past Supreme Knight James T. Mullen and adopted at the second Supreme Council meeting on May 12, 1883.[165] Shields used by medieval knights served as the inspiration. The emblem consists of a shield mounted on a Formée cross, which is an artistic representation of the cross of Christ. This represents the Catholic identity of the order.[166][non-primary source needed]

Mounted on the shield are three objects: a fasces; an anchor; and a dagger. In ancient Rome, the fasces was carried before magistrates as an emblem of authority. The order uses it as "symbolic of authority which must exist in any tightly-bonded and efficiently operating organization."[166][non-primary source needed] The anchor represents Christopher Columbus, patron of the order. The short sword, or dagger, was a weapon used by medieval knights. The shield as a whole, with the letters "K of C", represents "Catholic Knighthood in organized merciful action."[166][non-primary source needed]

Auxiliary groups

Women's auxiliaries

Many councils also have women's auxiliaries. At the turn of the 20th century two were formed by local councils and each took the name the Daughters of Isabella.[167][168] Using the same name, both groups expanded and issued charters to other circles but never merged. The newer organization renamed itself the Catholic Daughters of the Americas in 1921 and both have structures independent of the Knights of Columbus.[169][170] Other groups are known as the Columbiettes.[167] In the Philippines, the ladies' auxiliary is known as the Daughters of Mary Immaculate.[171]

A proposal in 1896 to establish councils for women did not pass, and was never proposed again.[74]

Columbian Squires

The Knights' official junior organization is the Columbian Squires. It has been described as “an athletic team, a youth group, a social club, a cultural and civic improvement association, a management training course, a civil rights organization and a spiritual development program all rolled into one.”[172] According to the McDonald, "The supreme purpose of the Columbian Squires is character building."[173]

It was founded in 1925 in Duluth, Minnesota by Brother Barnabas McDonald, F.S.C..[174][175][176] There are more than 25,000 Squires around the world.[172] The formation of new Squire Circles in the United States and Canada is discouraged as the Order desires to move youth activities from exclusive clubs into the local parish youth groups.[176]

Similar organizations

The Knights of Columbus is a member of the International Alliance of Catholic Knights, which includes fifteen fraternal orders such as the Knights of Saint Columbanus in Ireland, the Knights of Saint Columba in the United Kingdom, the Knights of Peter Claver in the United States, the Knights of the Southern Cross in Australia and New Zealand, the Knights of Marshall in Ghana, the Knights of Da Gama in South Africa, and the Knights of Saint Mulumba in Nigeria.[177] The Loyal Orange Institution, also known as the Orange Order, is a similar organization for Protestant Christians.[178][179]

See also

- Columbus Fountain

- Columbus School of Law

- Father Millet Cross

- James Cardinal Gibbons Memorial Statue

- The Knight on the Grid

- Knights of Columbus Hostel fire

- List of Knights of Columbus buildings

- List of Massachusetts State Deputies of the Knights of Columbus

- Manuscripta

- Parish Priest (book)

- Pope John Paul II Cultural Center

Notes

- ^ From 2007 to 2017, charitable giving was more than $1.55 billion.[12]

- ^ From 2007 to 2017, charitable giving was more than $1.55 billion.[12]

- ^ In the decade prior, the Order gave $1.475 billion and 673 million man hours.[53]

- ^ Over the previous decade, the Order gave $1.325 billion and 626 million man hours.[57]

- ^ The totals for the previous 12 years were $238 million donated and 65 million hours of service.[62]

- ^ The $88 million increase during 1956 was the greatest single increase in the Order's history.[71]

- ^ The first loan was to St. Rose Church in Meriden, Connecticut in 1896.[96][77]

- ^ Between 1977 and 1981, more than 1,000 new councils were created.[48]

- ^ As of December 31, 1898, there were 10,763 members in Massachusetts alone, which was second only to New York.[108]

- ^ The full guidelines are published on the episcopal conference's website.[145]

References

- ^ a b c Rundio, Steve (March 31, 2019). "Knights of Columbus conduct Exemplification Ceremony in Tomah". Tomah Journal. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Hubbard & Hubbard 2019, p. 75.

- ^ Hearn 1910.

- ^ Arce, Rose; Costello, Carol (October 22, 2012). "Election Day May Reveal Shift on Same-Sex Marriage". CNN. Turner Broadcasting System. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ^ Hubbard & Hubbard 2019, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e Hadro, Matt (August 5, 2019). "Knights of Columbus Donated More Than $185 Million to Charity in 2018". National Catholic Register. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c Long-Garcia, J.D. (August 13, 2019). "Knights of Columbus commit to helping asylum seekers at the southern border". No. September 2, 2019. America. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ^ a b "Knights of Columbus Scholarships Awarded in Califon". The Hunterdon County News. June 19, 2018. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c Ash, Jim (September 14, 2018). "Knights of Columbus celebrates milestone". Main Street Journal. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 256.

- ^ Kauffman, Christopher J. (2001). Patriotism and Fraternalism in the Knights of Columbus: A History of the Fourth Degree. Crossroad. ISBN 978-0-8245-1885-1. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Roberts, Tom (May 15, 2017). "Knights of Columbus' Financial Forms Show Wealth, Influence". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Comtois, James (February 27, 2016). "Knights of Columbus forms money manager, targets Catholic institutional investors". Pensions and Investments. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ a b "Knights of Columbus reach $100 billion in life insurance". Catholic News Agency. November 9, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 13.

- ^ "Father Michael McGivney". Connecticut Public Broadcasting Network. Archived from the original on September 16, 2013.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 18.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Glenn, Brian J. "Rhetoric of Fraternalism: Its Influence on the Development of the Welfare State 1900–1935". Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- ^ Brinkley & Fenster 2006, p. 51.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d Clark, Marlene (September 19, 2007). "KNIGHTS OF COLUMBUS FIND A HOME—AND KEEP IT". The Hartford Courant. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c Kauffman 1982, p. 22.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b Brinkley & Fenster 2006, p. 123.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, pp. 137–139.

- ^ Garitson, Elmer J. (June 29, 1922). "The Knights of Columbus and what they stand for". Oxford Register. p. 3. Retrieved December 9, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sweany 1923.

- ^ Flanagan 2017.

- ^ Kauffman 1995.

- ^ 268 U.S. 510 (1925)

- ^ "Pierce v. Society of Sisters". University of Chicago Kent School of Law. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 282.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 283.

- ^ Alley 1999, pp. 41–44.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, pp. 269–270.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 171.

- ^ Fry 1922, pp. 109–116.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 176.

- ^ Mecklin 2013.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982, p. 277.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 419.

- ^ "Knights of Columbus Leaders Praise John Paul II's Legacy to World's Laity". Catholic News Agency. April 29, 2011. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Knestout, Barry C. (November 30, 2019). "Knestout: Knights' generosity exemplary for all Catholics". The Roanoke Times. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 33.

- ^ a b Kauffman 2001. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKauffman2001 (help)

- ^ a b c Kauffman 1982, p. 428.

- ^ a b Borowski, Dave (November 5, 2014). "Mysteries of the regalia revealed". Catholic Herald. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hopfensperger, Jean (August 9, 2019). "Knights of Columbus work to refresh image, attract younger members". Star Tribune. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c Klemond, Susan (August 22, 2019). "Knights of Columbus efforts highlighted at annual convention". Pittsburgh Catholic Publishing Associates.

- ^ a b c d e DiStefano, Joseph N. (August 26, 2019). "Knights: Enough". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. E2. Retrieved December 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Pope praises Knights of Columbus for their charity, 'unfailing support'". Catholic News Agency. October 10, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ "Knights of Columbus donates funds, labor to New Haven Habitat project". The Register Citizen. December 20, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ "Knights of Columbus set charitable giving, volunteer records in 2011". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Draper, Electra (August 1, 2011). "Knights of Columbus begins annual convention today in Denver". The Denver Post. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Garver, Rob, Knights of Columbus: Founding Vision a Continued Success (PDF), vol. 33, Leaders, pp. 68–75, retrieved November 30, 2019

- ^ "Knights of Columbus Council 697 honored for service". The Journal Times. December 25, 2010. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Kotlarz, Amy (June 30, 2009). "Penfield man elected to N.Y. Knights of Columbus position". Catholic Courier. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Taylor, Frances Grandy (March 20, 2001). "THE KNIGHTS OF NEW HAVEN". The Hartford Courant. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Knight with a mission". Calgary Herald. Calgary, Alberta. May 18, 1997. p. 5. Retrieved December 9, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Franklin, James L. (August 8, 1982). "At 100, the K of C and Americanism". The Boston Globe. p. 1.

- ^ a b "K of C honored". The Anchor. Diocese of Fall River. June 8, 1984. p. 6. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 429.

- ^ a b c Kauffman 1982, p. 127.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 161.

- ^ a b c "FIFTY YEARS OLD". The Tampa Times. March 28, 1932. p. 4. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, pp. 166–67.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982, p. 320.

- ^ a b c Kauffman 1982, p. 388.

- ^ a b c "K. of C. Insurance at $650 million". The Eunice News. Eunice, Louisiana. March 28, 1957. p. 3. Retrieved December 9, 2019 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Siedenburg, SJ, Frederic (July 1920). New Catholic World. Vol. CXI (664 ed.). Paulist Press. p. 441. Retrieved December 7, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Increase in Membership". The Boston Globe. February 2, 1897. p. 4. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982, p. 126.

- ^ "Historical Currency Conversions". Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 377.

- ^ a b c d Kauffman 1982, p. 378.

- ^ Sullivan 2001.

- ^ a b Klemond, Susan (August 7, 2019). "Knights Supreme Convention: Anderson emphasizes assistance to refugees around the world". The Catholic Spirit. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Smith, Ryan (March 2, 2018). "Knights of Columbus sets insurance sales record for seventh straight year". Insurance Business America. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Catholic Mutual Finds Created". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. April 1, 2015. p. A8. Retrieved December 7, 2019 – via newspaper.com.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)

- ^ "Frackville man serves in Knights national office". Republican and Herald. Pottsville, Pennsylvania. October 7, 2014. p. A5. Retrieved December 7, 2019 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Sameea Kamal (July 11, 2013). "Knights of Columbus Insurance Program Passes $90 Billion Mark—Courant.com". Hartford Courant. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Knoxvillian elected to Knights' board of directors". The East Tennessee Catholic. October 2, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "People in Business for Sunday, March 24". The Grand Island Independent. March 23, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Gonzalez, Ramon (April 30, 2012). "Insuring members crucial to Knight's reason for existence". Western Catholic Reporter. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ a b "Ripple effect". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. August 9, 2011. p. A06. Retrieved December 7, 2019 – via newspaper.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Product Development for Customer Welfare (PDF), vol. 33, Leaders, p. 71, retrieved November 30, 2019

- ^ a b "Fortune 500—Knights of Columbus". CNN Money. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ "Knights Of Columbus". CNN Money. April 17, 2006. Retrieved December 7, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Fraternal chief's pay questioned". Tampa Bay Times. St. Petersburg, Florida. April 4, 1992. p. 54. Retrieved December 9, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Knights of Columbus chief named director of Vatican bank". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. November 27, 1990. p. 78. Retrieved December 9, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982, p. 428-429.

- ^ a b c Kauffman 1982, p. 413.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982, p. 397.

- ^ a b c Carey, Ann (August 31, 2008). "Knights of Columbus loan program propels projects in the diocese" (PDF). Today's Catholic. p. 20. Retrieved December 7, 2019.

- ^ "For 38th consecutive year, A.M. Best reaffirms top A++ rating for Knights of Columbus". July 11, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ O'Connor, Emma; Petrovic, Nina (September 5, 2019). "The Knights Of Columbus Are Massively Inflating Their Membership In Alleged Insurance Scheme, New Documents Suggest". BuzzFeedNews. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ Mares, Courtney (August 7, 2018). "Knights of Columbus pledge support for persecuted Christians". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Hadro, Matt (August 7, 2019). "At Knights convention, Kendrick Castillo remembered, honored as 'a hero'". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. xv.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982, p. 427.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 335.

- ^ Sweany 1923, p. 1.

- ^ Sweany 1923, p. 2.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982, p. 152.

- ^ a b "A Diverse Church". The Catholic University of America Archives. Archived from the original on April 22, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Lapomarda 1992, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Koehlinger 2004.

- ^ Brinkley & Fenster 2006, p. 171.

- ^ Connecticut Insurance Department 2018, p. 2.

- ^ a b Hubbard & Hubbard 2019, p. 76-77.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, pp. 375–376.

- ^ The Tablet, 7 September 2019, pp. 4–5.

- ^ "Bush Lauds Knights' Pro-Life Efforts, Pushes Faith-Based Programs". Catholic News Service. Archived from the original on October 4, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 411.

- ^ "Reagan, Ronald. "Remarks at the Centennial Meeting of the Supreme Council of the Knights of Columbus in Hartford, Connecticut", August 3, 1982. The American Presidency Project. (Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, ed.) University of California, Santa Barbara". presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ a b "Benedict XVI, Obama send greetings to K of C". Catholic News Agency. August 4, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Cooperman, Alan (August 4, 2004). "Bush Tells Catholic Group He Will Tackle Its Issues". The Washington Post. p. A4. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ "Indiana bishop urges Fightin' Irish to join Knights". Catholic News Agency. January 30, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982, p. 153.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 185.

- ^ Salvaterra 2002.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, pp. 138–143.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, pp. 169–175.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 178.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 414.

- ^ a b "About Catholic Information Service". Knights of Columbus. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 62.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982, p. 367.

- ^ Caplin; Drysdale (Winter 1999). "Voter Education vs. Partisan Politicking: What a 501(c)(3) Can and Cannot Do". The Grantsmanship Center Magazine. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on April 15, 2003. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ "Knights will keep up the fight on life, marriage issues". The Catholic Review. January 19, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ a b "Catholic Citizenship And Public Policy" (PDF). Knights of Columbus. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 302.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, pp. 364–365.

- ^ Larry Ceplair (2011). Anti-communism in Twentieth-Century America: A Critical History: A Critical History. ABC-CLIO. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-4408-0048-1.

- ^ Hallenius, Kenneth (October 6, 2019). "Notre Dame to award Evangelium Vitae Medal to Vicki Thorn, founder of Project Rachel post-abortion healing ministry". University of Notre Dame. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ McElwee, Jason J. (October 19, 2012). "Knights of Columbus Key Contributor Against Same-Sex Marriage". National Catholic Reporter. Kansas City, Missouri. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ Desmond, Joan Frawley (August 15, 2012). "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner? Cardinal Dolan Defends Invitation to Obama for Al Smith Banquet". National Catholic Register. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982, pp. 366–367.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, p. 366.

- ^ Bremer, Thomas S. (2014). Formed From This Soil: An Introduction to the Diverse History of Religion in America. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-32354-0.

- ^ Greenberg, David (June 28, 2002). "The Pledge of Allegiance: Why we're not one nation 'under God.'". Slate Magazine.

- ^ a b "The Knights of Columbus Celebrate 90 Years in Rome". Rome Reports. June 19, 2010. Archived from the original on June 22, 2010. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ "Socially Responsible Investment Guidelines". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Comtois, James (October 10, 2019). "Knights of Columbus Asset Advisors acquires Boston Advisors' institutional business". Pensions & Investments. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Filteau, Jerry (August 3, 2011). "Knights of Columbus to purchase Pope John Paul II center". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Roberts, Tom (August 17, 2011). "Knights buy John Paul II Cultural Center". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Mauro, J-P (January 30, 2019). "Explore the legacy of St. John Paul II at his National Shrine, in DC". Alteia. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ Boorstein, Michelle Boorstein Michelle (August 3, 2011). "Knights of Columbus to buy Pope John Paul II center". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ Singular 2005, p. 60.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, pp. 393–394.

- ^ Singular 2005, p. 38.

- ^ Singular 2005, p. 94.

- ^ "Representative John Boehner's Biography". Project Vote Smart. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ Singular 2005, p. 114.

- ^ Paulson, Michael (March 17, 2015). "Jeb Bush, 20 Years After Conversion, Is Guided by His Catholic Faith". The New York Times. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "Famous Knights of Columbus". Famous101. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ "Iconic Artifacts". The National Museum of the Marine Corps. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ Singular 2005, p. 64.

- ^ Singular 2005, p. 4.

- ^ "Floyd Patterson" (PDF). Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 30, 2011. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ Singular 2005, p. 30.

- ^ "1st Knight-of-Columbus-Bishop to Be Canonized". EWTN News. October 10, 2006. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b c "Official Knights of Columbus Emblems and Council Jewels" (PDF). Knights of Columbus. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Kauffman 1982, p. 125.

- ^ "About Us, Daughters of Isabella". Daughters of Isabella. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ "The History of the Catholic Daughters of the Americas". Catholic Daughters of America. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ Kauffman 1982, pp. 125–126.

- ^ "Brief History, Daughters of Mary Immaculate International". Daughters of Mary Immaculate International. Archived from the original on July 18, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Hallowell, Billy (February 8, 2013). "9 Faith-Based (and Secular) Alternatives to the Boy Scouts of America Amid Furor Over Gay Ban". The Blaze. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ^ "Church News". Valley Road Runner. February 25, 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ Djupe, Paul A. (2003). Encyclopedia of American Religion and Politics. Infobase Publishing.

- ^ "History of the Brothers in the U.S.A. since 1845". Manhattan College. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ^ a b Delorme, Rita H. "K. of C. Squires: the name is medieval, but their goals aren't". Southern Cross. Diocese of Savannah. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ "Member Orders". International Alliance of Catholic Knights. Archived from the original on March 14, 2007. Retrieved May 30, 2006.

- ^ Kaufmann 2007, p. 315.

- ^ Marchildon 2009, p. 8.

Works cited

- Alley, Robert S., ed. (1999). The Constitution & Religion: Leading Supreme Court Cases on Church and State. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-703-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Brinkley, Douglas; Fenster, Julie M. (2006). Parish Priest: Father Michael McGivney and American Catholicism. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-077684-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Dodge, William Wallace (1903). The Fraternal and Modern Banquet Orator: An Original Book of Useful Helps at the Social Session and Assembly of Fraternal Orders, College Entertainments, Social Gatherings and All Banquet Occasions. Chicago: Monarch Book Company.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Flanagan, Luke (2017). "Knights of Columbus Catholic Recreation Clubs in Great Britain, 1917–1919". In Malet, David; Anderson, Miriam J. (eds.). Transnational Actors in War and Peace: Militants, Activists, and Corporations in World Politics. Georgetown University Press. pp. 24–41. ISBN 978-1-62616-443-7.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Fry, Henry P. (1922). The Modern Ku Klux Klan. Boston: Small, Maynard & Company. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Hearn, Edward (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles G.; Pace, Edward A.; Pallen, Condé B.; Shahan, Thomas J.; Wynne, John J. (eds.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Encyclopedia Press (published 1913). pp. 670–671.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Hubbard, Robert; Hubbard, Kathleen (2019). Hidden History of New Haven. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-4082-9. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Kauffman, Christopher J. (1982). Faith and Fraternalism: The History of the Knights of Columbus, 1882–1982. Harper and Row. ISBN 978-0-06-014940-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- ——— (1995). "Knights of Columbus". In Venzon, Anne Cipriano; Miles, Paul L. (eds.). The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing (published 2013). pp. 321–322. ISBN 978-1-135-68453-2.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- ——— (2001). Patriotism and Fraternalism in the Knights of Columbus. New York: Crossroad Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8245-1885-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Kaufmann, Eric P. (2007). The Orange Order: A Contemporary Northern Irish History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920848-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Koehlinger, A. (December 1, 2004). ""Let Us Live for Those Who Love Us": Faith, Family, and the Contours of Manhood among the Knights of Columbus in Late Nineteenth-Century Connecticut". Journal of Social History. 38 (2): 455–469. doi:10.1353/jsh.2004.0126.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Lapomarda, S.J., Vincent A. (1992). The Knights of Columbus in Massachusetts (second ed.). Norwood, Massachusetts: Knights of Columbus Massachusetts State Council.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)[self-published source?]

- Marchildon, Gregory P. (2009). "Introduction". In Marchildon, Gregory P. (ed.). Immigration and Settlement, 1870–1939. History of the Prairie West. Vol. 2. Regina, Saskatchewan: University of Regina Press. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-0-88977-230-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- McGowan, Mark G. (1999). Waning of the Green: Catholics, the Irish, and Identity in Toronto, 1887-1922. McGill–Queen's Press—MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-1789-9.

- Mecklin, John (2013) [1924]. The Ku Klux Klan: A Study of the American Mind. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4733-8675-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Nuesse, C. Joseph (1990). The Catholic University of America: A Centennial History. Washington: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-0736-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Salvaterra, David L. (2002). "Review of Patriotism and Fraternalism in the Knights of Columbus: A History of the Fourth Degree by Christopher J. Kauffman". The Catholic Historical Review. 88 (1): 157–158. doi:10.1353/cat.2002.0048. ISSN 1534-0708. JSTOR 25026129.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Singular, Stephen (2005). By Their Works: Profiles of Men of Faith Who Made a Difference. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-116145-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Sullivan, Neil (2001). The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York. New York: Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Sweany, Mark J. (1923). Educational Work of the Knights of Columbus. Bureau of Education Bulletin. Vol. 22. Mark J. Sweaney, Director of the Knights of Columbus Educational Activities. Washington: Government Printing Office. hdl:2346/60378.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 31 (12th ed.). London: Encyclopædia Britannica Company. pp. 682–683.

- Egan, Maurice Francis; Kennedy, John James Bright (1920). The Knights of Columbus in Peace and War. Vol. 1. Knights of Columbus. ISBN 978-1-142-78398-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)[self-published source?]

- Bauernschub, John P. (1949). Fifty Years of Columbianism in Maryland. Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland State Council, Knights of Columbus.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)[self-published source?]

- ——— (1965). Columbianism in Maryland, 1897–1965. Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland State Council, Knights of Columbus.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)[self-published source?]