Blackbirding: Difference between revisions

Dippiljemmy (talk | contribs) →Robert Towns and the first shipments: some were on 1 or 2 or 3 year contracts |

Dippiljemmy (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

=== 1880-1885: Intense conflict and shifting of recruitment to the New Guinea islands === |

=== 1880-1885: Intense conflict and shifting of recruitment to the New Guinea islands === |

||

The violence and death surrounding the Queensland blackbirding trade intensified in the early 1880s. Local communities in the [[New Hebrides]] and the [[Solomon Islands]] had increased access to modern firearms which made their resistance to the blackbirders more robust. Well known vessels that experienced mortality amongst their crews while attempting to recruit Islanders included the ''Esperanza'' at [[Simbo]], ''Pearl'' at [[Rendova Island]], ''May Queen'' at [[Ambae Island]], ''Stormbird'' at [[Tanna (island)|Tanna]], the ''Janet Stewart'' at [[Malaita]] and the ''Isabella'' at [[Espiritu Santo]] amongst others.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238305901 |title=THE RECENT OUTRAGES IN THE SOUTH SEA ISLANDS. |newspaper=[[The Sydney Daily Telegraph]] |issue=522 |location=New South Wales, Australia |date=4 March 1881 |accessdate=9 July 2019 |page=3 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article201983672 |title=ANOTHER SOUTH SEA MASSACRE. |newspaper=[[The Age]] |issue=8371 |location=Victoria, Australia |date=13 December 1881 |accessdate=9 July 2019 |page=3 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> Officers of [[Royal Navy]] warships attempting punitive action were not exempt as targets with Lieutenant Bower and five crew of the [[HMS Sandfly (1872)|HMS ''Sandfly'']] being killed in the [[Nggela Islands]]<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13477810 |title=MASSACRE OF LIEUTENANT BOWER AND FIVE SEAMEN OF H.M.S. SANDFLY. |newspaper=[[The Sydney Morning Herald]] |issue=13,314 |location=New South Wales, Australia |date=2 December 1880 |accessdate=9 July 2019 |page=7 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> and Lieutenant Luckcraft of the [[HMS Cormorant (1877)|HMS ''Cormorant'']] being shot dead at [[Espiritu Santo]].<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article202524676 |title=MURDER IN THE SOUTH SEA ISLANDS. |newspaper=[[The Age]] |issue=8463 |location=Victoria, Australia |date=31 March 1882 |accessdate=9 July 2019 |page=3 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> Reprisals from British naval ships based at the [[Australia Station]] were frequent and substantial. |

The violence and death surrounding the Queensland blackbirding trade intensified in the early 1880s. Local communities in the [[New Hebrides]] and the [[Solomon Islands]] had increased access to modern firearms which made their resistance to the blackbirders more robust. Well known vessels that experienced mortality amongst their crews while attempting to recruit Islanders included the ''Esperanza'' at [[Simbo]], ''Pearl'' at [[Rendova Island]], ''May Queen'' at [[Ambae Island]], ''Stormbird'' at [[Tanna (island)|Tanna]], the ''Janet Stewart'' at [[Malaita]] and the ''Isabella'' at [[Espiritu Santo]] amongst others.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238305901 |title=THE RECENT OUTRAGES IN THE SOUTH SEA ISLANDS. |newspaper=[[The Sydney Daily Telegraph]] |issue=522 |location=New South Wales, Australia |date=4 March 1881 |accessdate=9 July 2019 |page=3 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article201983672 |title=ANOTHER SOUTH SEA MASSACRE. |newspaper=[[The Age]] |issue=8371 |location=Victoria, Australia |date=13 December 1881 |accessdate=9 July 2019 |page=3 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> Officers of [[Royal Navy]] warships attempting punitive action were not exempt as targets with Lieutenant Bower and five crew of the [[HMS Sandfly (1872)|HMS ''Sandfly'']] being killed in the [[Nggela Islands]]<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13477810 |title=MASSACRE OF LIEUTENANT BOWER AND FIVE SEAMEN OF H.M.S. SANDFLY. |newspaper=[[The Sydney Morning Herald]] |issue=13,314 |location=New South Wales, Australia |date=2 December 1880 |accessdate=9 July 2019 |page=7 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> and Lieutenant Luckcraft of the [[HMS Cormorant (1877)|HMS ''Cormorant'']] being shot dead at [[Espiritu Santo]].<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article202524676 |title=MURDER IN THE SOUTH SEA ISLANDS. |newspaper=[[The Age]] |issue=8463 |location=Victoria, Australia |date=31 March 1882 |accessdate=9 July 2019 |page=3 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> Reprisals from British naval ships based at the [[Australia Station]] were frequent and substantial. The [[HMS Emerald (1876)|HMS ''Emerald'']] under Captain W.H. Maxwell went on an extensive [[punitive expedition]], [[shell (projectile)|shelling]] and destroying numerous villages<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103813346 |title=PUNISHING THE SOUTH SEA ISLANDERS. |newspaper=[[The Goulburn Herald And Chronicle]] |location=New South Wales, Australia |date=2 February 1881 |accessdate=12 July 2019 |page=4 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref>, while [[Royal Marines|marines]] of the [[HMS Cormorant (1877)|HMS ''Cormorant'']] executed various Islanders suspected of killing white men.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article201989240 |title=PUNISHMENT OF THE SANDFLY MURDERERS. |newspaper=[[The Age]] |issue=8306 |location=Victoria, Australia |date=28 September 1881 |accessdate=12 July 2019 |page=1 (Supplement to The Age) |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> Captain Dawson of the [[HMS Miranda (1879)|HMS ''Miranda'']] led a mission to [[Ambae Island]], killing native people and burning villages,<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article201991915 |title=THE MAY QUEEN OUTRAGE. |newspaper=[[The Age]] |issue=8289 |location=Victoria, Australia |date=8 September 1881 |accessdate=12 July 2019 |page=3 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> while the [[HMS Diamond (1874)|HMS ''Diamond'']] went on a "savage-hunting expedition" throughout the [[Solomon Islands]].<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238477465 |title=CRUISE OF H.M.S. DIAMOND. |newspaper=[[The Sydney Daily Telegraph]] |issue=986 |location=New South Wales, Australia |date=4 September 1882 |accessdate=12 July 2019 |page=3 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> At [[Ambrym]], the marines of the [[HMS Dart (1882)|HMS ''Dart'']] under Commander Moore, surrounded villages and massacred locals for the killing of Captain Belbin of the blackbirding ship ''Borough Belle''.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article111024907 |title=The Outrage at Ambrym. |newspaper=[[Evening News]] |issue=4996 |location=New South Wales, Australia |date=22 August 1883 |accessdate=12 July 2019 |page=8 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> Likewise, the [[HMS Undine (1881)|HMS ''Undine'']] patrolled the islands, protecting the crews of blackbirding vessels such as the ''Ceara'' from mutinies of the labour recruits.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3436515 |title=OUTRAGES IN THE SOUTH SEA ISLANDS. |newspaper=[[The Brisbane Courier]] |volume=XXXIX, |issue=8,387 |location=Queensland, Australia |date=26 November 1884 |accessdate=12 July 2019 |page=3 |via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> |

||

=== The later years of recruiting === |

=== The later years of recruiting === |

||

Revision as of 08:26, 12 July 2019

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

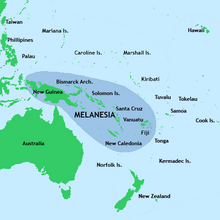

Blackbirding involves the coercion of people through deception and/or kidnapping to work as unpaid or poorly paid labourers in countries distant to their native land. The term has been most commonly applied to the large-scale taking of people indigenous to the numerous islands in the Pacific Ocean during the 19th and 20th centuries. These blackbirded people were called Kanakas or South Sea Islanders. The owners, captains and crew of the ships involved in the acquisition of these labourers were termed blackbirders. The demand for this kind of cheap labour principally came from European colonists in New South Wales, Peru, Queensland, Samoa, New Caledonia, Fiji, Tahiti, Mexico and Guatemala. Labouring on sugarcane, cotton and coffee plantations in these lands was the main usage of blackbirded labour but they were also exploited in other industries.

Blackbirding ships began operations in the Pacific from the 1840s and continued into the early 1910s. In the 1860s, Peruvian blackbirders sought workers at their haciendas and to mine the guano deposits on the Chincha Islands.[2] From the late 1860s, the blackbirding trade focused on supplying labourers to plantations, particularly those producing sugar-cane in Queensland and Fiji.[3][4]

Examples of blackbirding outside the South Pacific include the early days of the pearling industry in Western Australia at Nickol Bay and Broome, where Aboriginal Australians were blackbirded from the surrounding areas.

The practice of blackbirding has continued to the present day, in certain developing countries. One example is the kidnapping and coercion, often at gunpoint, of indigenous peoples in Central America to work as plantation labourers in the region. They are subjected to poor living conditions, are exposed to heavy pesticide loads, and do hard labour for very little pay.[5]

Etymology

The term may have been formed directly as a contraction of "blackbird catching"; "blackbird" was a slang term for the local indigenous people.

New South Wales

The first major blackbirding operation in the Pacific was conducted out of Twofold Bay in New South Wales. A shipload of 65 Melanesian labourers arrived in Boyd Town on 16 April 1847 on board the Velocity, a vessel under the command of Captain Kirsopp and chartered by Benjamin Boyd.[6] Boyd was a Scottish colonist who wanted cheap labourers to work at his large pastoral leaseholds in the colony of New South Wales. He financed two more procurements of South Sea Islanders, 70 of which arrived in Sydney in September 1847, and another 57 in October of that same year.[7][8] Many of these Islanders soon absconded from their workplaces and were observed starving and destitute on the streets of Sydney.[9] Reports of violence, kidnap and murder used during the recruitment of these labourers surfaced in 1848 with a closed-door enquiry choosing not to take any action against Boyd or Kirsopp.[10] The experiment of exploiting Melanesian labour was discontinued in Australia until Robert Towns recommenced the practice in Queensland in the early 1860s.

Peru

For several months between 1862–63, crews on Peruvian and Chilean ships combed the islands of Polynesia, from Easter Island in the eastern Pacific to the Gilbert Islands (now Kiribati) in the west, seeking workers to fill an extreme labour shortage in Peru. Joseph Charles Byrne, an Irish speculator, received financial backing to import South Sea Islanders as indentured workers. Byrne's ship, Adelante, set forth across the Pacific and at Tongareva in the northern Cook Islands he was able to acquire 253 recruits of which more than half were women and children. The Adelante returned to the Peruvian port of Callao where the human cargo were sold off and sent to work as plantation labourers and domestic servants. A considerable profit was made by the scheme's financiers and almost immediately other speculators and ship owners set out to make money on Polynesian labour.[2]

Easter Island mass-kidnapping

Eight Peruvian ships organised under Captain Marutani of the Rosa y Carmen conducted an armed operation at Easter Island where, over several days, the combined crews systematically surrounded villages and captured as many of the Islanders as possible. In these raids and others like them that occurred at Easter Island during this period, 1407 people were taken for the Peruvian labour trade. This represented a third of the island's population. In the following months, the Rosa y Carmen together with about 30 other vessels involved in recruiting for Peru, kidnapped or deceptively obtained people throughout Polynesia. Captain Marutani's vessel alone took people from Niue, Samoa and Tokelau, as well as those that he kidnapped from Easter Island.[2]

'Ata mass-kidnapping

In June 1863 about 350 people were living on 'Ata, an atoll in Tonga. Captain Thomas James McGrath of the Tasmanian whaler Grecian, having decided that the new slave trade was more profitable than whaling, went to the atoll and invited the islanders on board for trading. However, once almost half of the population was on board, he ordered the ship's compartments locked, and the ship departed. These 144 people never returned to their homes. The Grecian met with a Peruvian slave vessel, the General Prim, and the islanders were transferred to this ship which transported them to Callao. Due to new government regulations in Peru against the blackbirding trade, the islanders were not allowed to disembark and remained aboard for many weeks while their repatriation was organised. Finally on 2 October 1863, by which time many of the imprisoned 'Ata people had died or were dying from neglect and disease, a vessel was organised to take them back. However, this ship dumped the Tongans on uninhabited Cocos Island. A month later the Peruvian warship Tumbes went to rescue the remaining 38 survivors and took them to the Peruvian port of Paita, where they probably died.[2]

Deception at Tuvalu

The Rev. A. W. Murray, the earliest European missionary in Tuvalu,[11] described the practices of blackbirders in the Ellice Islands. He said they promised islanders that they would be taught about God while working in coconut oil production, but the slavers' intended destination was the Chincha Islands in Peru. Rev. Murray reported that in 1863, about 180 people[12] were taken from Funafuti and about 200 were taken from Nukulaelae,[13] leaving fewer than 100 of the 300 recorded in 1861 as living on Nukulaelae.[14][15]

Extreme death rate

The Peruvian labour trade in Polynesians was short-lived, only lasting from 1862 to 1863. In this period an estimated 3634 Polynesians were recruited. Over 2000 died from disease, starvation or neglect either aboard the blackbirding ships or at the places of labour they were sent to. The Peruvian government shut down the operation in 1863 and ordered the repatriation of those who survived. A smallpox and dysentery outbreak in Peru accompanied this operation resulting in the death of a further 1030 Polynesian labourers. Some of the islanders survived long enough to bring these contagious diseases to their home islands causing local epidemics and additional mortality. By 1866, only around 250 of those recruited had survived with about 100 of these remaining in Peru. The death rate was therefore 93%.[2]

Queensland

The Queensland labour trade in South Sea Islanders, or Kanakas as they were commonly termed, was in operation from 1863 to 1908, a period of 45 years. Some 55,000 to 62,500 were brought to Australia,[16] most being recruited or blackbirded from islands in Melanesia, such as the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu), the Solomon Islands and the islands around New Guinea. Although the process of acquiring these "indentured labourers" varied from violent kidnapping at gunpoint to relatively acceptable negotiation, most of the people affiliated with the trade were regarded as blackbirders.[17] The majority of those taken were male and around one quarter were under the age of sixteen.[18] In total, approximately 15,000 Kanakas died while working in Queensland, a figure which does not include those who expired in transit or who were killed in the recruitment process. This represents a mortality rate of 30%, which is high considering most were only on three year contracts.[19] It is also strikingly similar to the estimated 33% death rate of African slaves in the first three years of being imported to America.[20]

Robert Towns and the first shipments

In 1863, Robert Towns, a British sandalwood and whaling merchant residing in Sydney, wanted to profit from the world-wide cotton shortage due to the American Civil War. He bought a property he named Townsvale on the Logan River south of Brisbane, and planted 400 acres of cotton. Towns wanted cheap labour to harvest and prepare the cotton and decided to import Melanesian labour from the Loyalty Islands and the New Hebrides. Captain Grueber together with labour recruiter Henry Ross Lewin aboard the Don Juan, brought 73 South Sea Islanders to the port of Brisbane in August 1863.[21] Towns specifically wanted adolescent males recruited and kidnapping was reportedly employed in obtaining these boys.[22][23] Over the following two years, Towns imported around 400 more Melanesians to Townsvale on one to three year terms of labour. They came on the vessels Uncle Tom (Captain Archer Smith) and Black Dog (Captain Linklater). In 1865, Towns obtained large land leases in Far North Queensland and funded the establishment of the port of Townsville. He organised the first importation of South Sea Islander labour to that port in 1866. They came aboard Blue Bell under Captain Edwards.[24] Towns paid his Kanaka labourers in trinkets instead of cash at the end of their working terms. He claimed that blackbirded labourers were "savages who did not know the use of money" and therefore did not deserve cash wages.[25] Apart from a small amount of Melanesian labour imported for the beche-de-mer trade around Bowen,[26] Robert Towns was the primary exploiter of blackbirded labour up til 1867.

Expansion and legislation

The high demand for very cheap labour in the sugar and pastoral industries of Queensland, resulted in Towns' main labour recruiter, Henry Ross Lewin, and another recruiter by the name of John Crossley opening their services to other land-owners. In 1867, the vessels King Oscar, Spunkie, Fanny Nicholson and Prima Donna returned with close to 1000 Kanakas who were offloaded in the ports of Brisbane, Bowen and Mackay. This influx, together with information that the recently arrived labourers were being sold for £2 each and that kidnapping was at least partially used during recruitment, raised fears of a burgeoning new slave trade.[27][28][29][30] These fears were realised when French officials in New Caledonia complained that Crossley had stolen half the inhabitants of a village in Lifou, and in 1868 a scandal evolved when Captain McEachern of the ship Syren anchored in Brisbane with 24 dead islander recruits and reports that the remaining ninety on board were taken by force and deception. Despite the controversy, no action was taken against McEachern or Crossley.[31][32]

Many members of the Queensland government were already either invested in the labour trade or had Kanakas actively working on their land holdings. Therefore, the 1868 legislation on the trade in the form of the Polynesian Labourers Act that was brought in due to the Syren debacle, requiring every ship to be licensed and carry a government agent to observe the recruitment process, was poor in protections and even more poorly enforced.[31] Government agents were often corrupted by bonuses paid for labourers 'recruited,' or blinded by alcohol, and did little or nothing to prevent sea-captains from tricking islanders on-board or otherwise engaging in kidnapping with violence.[33] The Act also stipulated that the Kanakas were to be contracted for no more than 3 years and be paid £18 for their work. This was an extremely low wage that was only paid at the end of their three years of work. Additionally, a system whereby the Islanders were heavily influenced to buy overpriced goods of poor quality at designated shops before they returned, robbed them further.[34] The Act, instead of protecting the South Sea Islanders, actually gave legitimacy to a kind of slavery in Queensland.[35]

Certain officials in London were concerned enough with the situation to order a vessel of the Royal Navy based at the Australia Station in Sydney to do a cruise of investigation. In 1869, The Rosario under Captain George Palmer managed to intercept a blackbirding ship loaded with Islanders at Fiji. This ship, the Daphne under command of Captain Daggett and licensed in Queensland to Henry Ross Lewin, was described by Palmer as being fitted out "like an African slaver". Even though there was a government agent on board, the Islanders recruited appeared in poor condition and, having no understanding of English and no interpreter, had little idea of why they were being transported. Palmer seized the ship, freed the Kanakas and arrested both Captain Daggett and the ship's owner Thomas Pritchard for slavery. Daggett and Pritchard were taken to Sydney to be tried but all charges were quickly dismissed and the prisoners discharged. Furthermore, Sir Alfred Stephen, the Chief Justice of the New South Wales Supreme Court found that Captain Palmer had illegally seized the Daphne and ordered him to pay reparations to Daggett and Pritchard. No evidence or statements were taken from the Islanders. This decision, which overrode the obvious humanitarian actions of a senior officer of the Royal Navy, gave further legitimacy to the blackbirding trade out of Queensland and allowed it to flourish.[35]

The Kanaka trade in the 1870s

Recruiting of South Sea Islanders soon became an established industry with labour vessels from across eastern Australia obtaining Kanakas for both the Queensland and Fiji markets. Captains of such ships would get paid about 5 shillings per recruit in "head money" incentives, while the owners of the ships would sell the Kanakas from anywhere between £4 to £20 per head.[36] The Kanakas were sometimes offloaded at the ports in Queenlsand with metal discs imprinted with a numeral hung around their neck making for easy identification for their buyers.[37] Maryborough and Brisbane became important centres for the trade with vessels such as Spunkie, Jason and Lyttona making frequent recruiting journeys out of these ports. Reports of blackbirding, kidnap and violence were made against these vessels with Captain Winship of the Lyttona being accused of kidnapping and importing Kanaka boys aged between 12 and 15 years for the plantations of George Raff at Caboolture.[38] The crew of the Spunkie were involved in shooting dead recruits, while charges of kidnap were made against Captain John Coath of the Jason.[39] Only Captain Coath was brought to trial and despite being found guilty, he was soon pardoned and allowed to re-enter the recruiting trade. Up to 45 of the Kanakas brought in by Coath died on plantations around the Mary River.[40] Meanwhile, the famous recruiter Henry Ross Lewin was charged with the rape of a pubescent Islander girl. Despite strong evidence, Lewin was acquitted and the girl was later sold in Brisbane for £20.[31]

By the 1870s, South Sea Islanders were being put to work not only in cane-fields along the Queensland coast but were also widely used as shepherds upon the large sheep stations in the interior and as pearl divers in the Torres Strait. They were taken as far west as Hughenden, Normanton and Blackall. In these isolated places the Kanakas were at even more risk of being subjected to violent and neglectful treatment. For instance, a number of Islanders died of malnutrition and scurvy on the long journey from Rockhampton to Bowen Downs Station.[41] Beatings of the Islander shepherds were condoned by the police[42] and on occasions when the Kanakas would fight back and kill their overseers, they were hunted down and shot by the Native Police.[43] When the owners of the properties they were labouring on went bankrupt, the Islanders would often either be abandoned[44] or sold as part of the estate to a new owner.[45] In the Torres Strait, Kanakas were left at isolated pearl fisheries such as the Warrior Reefs for years with little hope of being returned home.[46] Many of the pearling operations and associated labour vessels such as the Woodbine and the Christina in this region were owned by James Merriman who held the position of Mayor of Sydney.[47]

Poor conditions at the sugar plantations led to regular outbreaks of disease and death. The Maryborough plantations and the labour vessels operating out of that port became notorious for high mortality rates of Kanakas. Ships such as the Jason would arrive with Islanders either dead or infected with diseases such as measles[48] which would spread to the labourers at the plantations.[49] From 1875 to 1880, at least 443 Kanakas died in the Maryborough region from gastrointestinal and pulmonary disease at a rate 10 times above average. The Yengarie, Yarra Yarra and Irrawarra plantations belonging to Robert Cran were particularly bad. An investigation revealed that that the Islanders were overworked, underfed, not provided with medical assistance and that the water supply was a stagnant drainage pond.[50] At the port of Mackay, the labour schooner Isabella arrived with half the Kanakas recruited dying on the voyage from dysentery,[51] while Captain John Mackay (after whom the city of Mackay is named), arrived at Rockhampton in the Flora with a cargo of Kanakas, of which a considerable number were in a dead or dying condition.[52][53]

As the blackbirding activities increased and the detrimental results became more understood, resistance by the Islanders to this recruitment system grew. Labour vessels were regularly repelled from landing at many islands by local people. Recruiter, Henry Ross Lewin, was killed at Tanna Island, the crew of the May Queen were killed at Pentecost Island, while the captain and crew of the Dancing Wave were killed at the Nggela Islands. Blackbirding vessels such as the Mystery under Captain Kilgour attacked villages, shooting the residents and burning their houses.[54] Ships of the Royal Navy were also called upon to deliver severe summary punishment upon islands involved in killings of blackbirding crews. For instance, HMS Beagle under Captain de Houghton and HMS Wolverine under Commodore John Crawford Wilson conducted several missions in the late 1870s that involved indiscriminate bombardment of villages, raids by marines, burning of houses, destruction of crops and the hangings of Islanders from the yardarms.[55][56] One of these missions involved the assistance of the armed crew of the blackbirding vessel Sybil commanded by Captain Satini.[57] Violence was not just isolated to the islands, with Kanakas being used by plantation owners such as John Ewen Davidson to kill and remove Aboriginal Australians from the land.[58] Additionally, two South Sea Islanders were hanged in Maryborough for the rape of a white woman, these being the first legal executions in that town.[59]

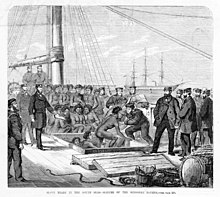

1880-1885: Intense conflict and shifting of recruitment to the New Guinea islands

The violence and death surrounding the Queensland blackbirding trade intensified in the early 1880s. Local communities in the New Hebrides and the Solomon Islands had increased access to modern firearms which made their resistance to the blackbirders more robust. Well known vessels that experienced mortality amongst their crews while attempting to recruit Islanders included the Esperanza at Simbo, Pearl at Rendova Island, May Queen at Ambae Island, Stormbird at Tanna, the Janet Stewart at Malaita and the Isabella at Espiritu Santo amongst others.[60][61] Officers of Royal Navy warships attempting punitive action were not exempt as targets with Lieutenant Bower and five crew of the HMS Sandfly being killed in the Nggela Islands[62] and Lieutenant Luckcraft of the HMS Cormorant being shot dead at Espiritu Santo.[63] Reprisals from British naval ships based at the Australia Station were frequent and substantial. The HMS Emerald under Captain W.H. Maxwell went on an extensive punitive expedition, shelling and destroying numerous villages[64], while marines of the HMS Cormorant executed various Islanders suspected of killing white men.[65] Captain Dawson of the HMS Miranda led a mission to Ambae Island, killing native people and burning villages,[66] while the HMS Diamond went on a "savage-hunting expedition" throughout the Solomon Islands.[67] At Ambrym, the marines of the HMS Dart under Commander Moore, surrounded villages and massacred locals for the killing of Captain Belbin of the blackbirding ship Borough Belle.[68] Likewise, the HMS Undine patrolled the islands, protecting the crews of blackbirding vessels such as the Ceara from mutinies of the labour recruits.[69]

The later years of recruiting

Joe Melvin, an investigative journalist who, undercover, in 1892 joined the crew of Queensland blackbirding ship Helena, found no instances of intimidation or misrepresentation and concluded that the Islanders recruited did so "willingly and cannily".[70] Many died during the voyage due to unsanitary conditions,[citation needed] and in the fields due to the hard manual labour.[71]

Repatriation

The majority of the 10,000 Pacific Islanders remaining in Australia in 1901 were compulsorily repatriated from 1906–08 under the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901.[72] Those who were married to an Australian were exempt from compulsory repatriation. Today, the descendants of those who remained are officially referred to as South Sea Islanders. A 1992 census of South Sea Islanders reported around 10,000 descendants living in Queensland. Fewer than 3,500 were reported in the 2001 Australian census.[16]

Some commentators have drawn parallels between blackbirding and the early 21st century recruitment of labour under the 457 visa scheme.[73]

Fiji

The blackbirding era began in Fiji in 1865 when the first New Hebridean and Solomon Island labourers were transported there to work on cotton plantations. The American Civil War had cut off the supply of cotton to the international market when the Union blockaded southern ports. Cotton cultivation was potentially an extremely profitable business. Thousands of European planters flocked to Fiji to establish plantations but found the natives unwilling to adapt to their plans. They sought labour from the Melanesian islands. On 5 July 1865 Ben Pease received the first licence to provide 40 labourers from the New Hebrides to Fiji.[74]

The British and Queensland governments tried to regulate this recruiting and transport of labour. Melanesian labourers were to be recruited for a term of three years, paid three pounds per year, issued with basic clothing and given access to the company store for supplies. Most Melanesians were recruited by deceit, usually being enticed aboard ships with gifts, and then locked up. The living and working conditions for them in Fiji were worse than those suffered by the later Indian indentured labourers. In 1875, the chief medical officer in Fiji, Sir William MacGregor, listed a mortality rate of 540 out of every 1000 labourers. After the expiry of the three-year contract, the government required captains to transport the labourers back to their villages, but most ship captains dropped them off at the first island they sighted off the Fiji waters. The British sent warships to enforce the law (Pacific Islanders' Protection Act of 1872) but only a small proportion of the culprits were prosecuted.[citation needed]

A notorious incident of the blackbirding trade was the 1871 voyage of the brig Carl, organised by Dr James Patrick Murray,[75] to recruit labourers to work in the plantations of Fiji. Murray had his men reverse their collars and carry black books, so to appear to be church missionaries. When islanders were enticed to a religious service, Murray and his men would produce guns and force the islanders onto boats. During the voyage Murray shot about 60 islanders. He was never brought to trial for his actions, as he was given immunity in return for giving evidence against his crew members.[33][75] The captain of the Carl, Joseph Armstrong, was later sentenced to death.[75][76]

Beginning in 1879, British planters arranged for the transport of Indian indentured labourers in Fiji. The number of Melanesian labourers declined, but they were still being recruited and employed in such places as sugar mills and ports, until the start of the First World War. In addition, as recounted by writer Jack London, the British and Queensland ships often used black crews, sometimes recruited among the islanders. Most of the Melanesians recruited were males. After the recruitment ended, those who chose to stay in Fiji took Fijian wives and settled in areas around Suva. Their multi-cultural descendants identify as a distinct community but, to outsiders, their language and culture cannot be distinguished from native Fijians.

Descendants of Solomon Islanders have filed land claims to assert their right to traditional settlements in Fiji: a group living at Tamavua-i-Wai in Fiji received a High Court verdict in their favour on 1 February 2007. The court refused a claim by the Seventh-day Adventist Church to force the islanders to vacate the land on which they had been living for seventy years.[77]

Tahiti

In 1863, British capitalist William Stewart set up the Tahiti Cotton and Coffee Plantation Company at Atimaono on the south-west coast of Tahiti. Initially Stewart used imported Chinese coolie labour but soon shifted to blackbirded Polynesian labour to work the plantation. Bully Hayes, an American ship-captain who achieved notoriety for his activities in the Pacific from the 1850s to the 1870s, arrived in Papeete, Tahiti in December 1868 on his ship Rona with 150 men from Niue. Hayes offered them for sale as indentured labourers.[33] The French Governor of Tahiti, who was invested in the company, used government ships such as the Lucene to recruit South Sea Islanders for Stewart. These people were unloaded in a "half-naked and wholly starved" condition and on arrival at the plantation they were treated as slaves. Captain Blackett of the vessel Moaroa, was also chartered by Stewart to acquire labourers. In 1869, Blackett bought 150 Gilbert Islanders from another blackbirding ship for ₤5 per head. On transferring them to the Moaroa, the islanders, including another 150 already imprisoned on the vessel, rebelled killing Blackett and some of the crew. The remaining crew managed to isolate the islanders to a part of the ship and then used explosives to blow them up. Close to 200 people were killed in this incident with the Moaroa still able to offload about 60 surviving labourers at Tahiti.[78][79]

Conditions at the Atimaono plantation were appalling with long hours, heavy labour, poor food and inadequate shelter being provided. Harsh punishment was meted out to those who did not work and sickness was prevalent. The mortality rate for one group of blackbirded labourers at Atimaono was around 80%.[80] William Stewart died in 1873 and the Tahiti Cotton and Coffee Plantation Company went bankrupt a year later.

Samoa

In the late 1850s, German merchant Johann Cesar VI. Godeffroy, established a trading company based at Apia on the island of Upolu in Samoa. His company, J.C. Godeffroy & Sohn, was able to obtain large tracts of land from the indigenous population at times of civil unrest by selling firearms and exacerbating factional conflict. By 1872, the company owned over 100,000 acres on Upolu and greatly expanded their cotton and other agricultural plantations on the island. Cheap labour was required to work these plantations and the blackbirding operations of the Germans expanded at this time. After initially utilising people from Niue, the company sent labour vessels to the Gilbert Islands and the Nomoi Islands, exploiting food shortages there to recruit numerous people for their plantations in Samoa. Men, women and children of all ages were taken, separated and sent to work in harsh conditions with many succumbing to illness and poor diet.[81]

In 1880 the company became known as Deutsche Handels und Plantagen Gesellschaft (DHPG) and had further expanded their Samoan plantations. Labour recruitment at this stage turned to New Britain, New Ireland and the Solomon Islands. The German blackbirding vessel, the Upolu, became well-known in the area and was involved in several conflicts with islanders while recruiting.[82] Imported Chinese workers eventually became more favourable but labour recruiting from Melanesian islands continued til at least the transfer of power from the Germans to New Zealand at the start of World War I.[83]

Large British and American plantations which owned blackbirding vessels or exploited blackbirded labour also existed in colonial Samoa. The W & A McArthur Company representing Anglo-Australian interests was one of these[81] and recruiting vessels such as the Ubea, Florida and Maria were based in Samoa.[36] In 1880, the crew of the British blackbirding ship, the Mary Anderson, was involved in shooting recruits on board,[84] while in 1894 the Aele was involved in recruiting starving Gilbert Islanders.[85]

Mexico and Guatemala

In the late 1880s a worldwide boom in coffee demand fuelled the expansion of coffee growing in many regions including the south-west of Mexico and in neighbouring Guatemala. This expansion resulted in local labour shortages for the European plantation owners and managers in these areas. William Forsyth, an Englishman with expert knowledge on tropical plantations, promoted a scheme of recruiting people from the Gilbert Islands to counteract the shortage of workers in Mexico and Guatemala. In 1890, Captain Luttrell of the vessel Helen W. Almy was chartered and sent out to the Pacific where he recruited 300 Gilbert Islanders. They were offloaded in Mexico and sent to work at a coffee plantation near Tapachula owned by an American named John Magee. By 1894, despite supposedly having a three-year contract, none had been returned home and only 58 were still living.[86]

In 1891, the barque Tahiti under command of Captain Ferguson was assigned to bring another load of Gilbert Islanders to Tapachula. This ship acquired around 370 islanders including about 100 children. While bringing its human cargo to the Americas, the Tahiti suffered storm damage and was forced to anchor in Drakes Bay north of San Francisco. Amid accusations of slavery and blackbirding, Ferguson transferred command of the ship to another officer and abandoned the islanders in what amounted to a floating prison. Repairs were delayed for months and in early 1892, the Tahiti was found capsized with all but a few survivors drowned to death.[87][88]

Despite this tragedy another ship, the Montserrat, was fitted out to contract more Gilbert Islanders, this time for coffee plantations in Guatemala. Ferguson was again employed, but this time as recruiter not as captain. A journalist aboard the Montserrat described the recruiting of islanders as clear slavery and even though British naval officers in the region boarded the vessel for inspection, an understanding existed whereby the process was legitimised.[89] The Montserrat sailed to Guatemala with around 470 islanders and once disembarked they were sold for $100 each and force marched 70 miles to the plantations in the highlands. Overwork and disease killed around 200 of them.[86]

Approximately 1200 Gilbert Islanders were recruited in three shiploads for the Mexican and Guatemalan coffee plantations. Only 250 survived, most of these being returned to their homeland in two voyages in 1896 and 1908. This represented a mortality rate of 80%.[86]

Resistance and conflict

Islanders fought back and sometimes were able to resist those engaged in blackbirding. Historic events in Melanesia are being assessed in the context of blackbirding, and with the addition of new material from indigenous oral histories and interpreting to acknowledge indigenous agency.[90] The practice of blackbirding attracted significant public attention in Great Britain after native people killed Anglican missionary John Coleridge Patteson, Bishop of Melanesia, in September 1871 on Nukapu in what is now Temotu Province, Solomon Islands. His death from the beginning was interpreted as resistance by local people to kidnapping and forced labor. Patteson is considered a martyr by the Anglican Church. A few days before his death, one of the local men had been killed by blackbirders and five others were abducted.[90]

However, a 2010 article argues for a different precipitating event. When Patteson tried to persuade islanders to release their children to him to be educated in a distant Christian mission school, they did not want to lose their children to him. The bishop’s persistence and failure to interpret the islanders’ signals of resistance caused his demise.[90] An alternative theory is that Patteson had disrupted the local hierarchy, and especially threatened the patriarchal order.[90]

At the time, Patteson's death caused outrage in England and contributed to the government's cracking down to try to control the abusive aspects of blackbirding. Great Britain annexed Fiji as a way to suppress such slavery.

Role of the British Navy

The expansion of plantations in Fiji and in Samoa, as well as sugar plantations in Australia, also created market destinations for blackbirders. Ships also called at the islands of Melanesia and Micronesia, taking off their workers for other places. So many ships entered the blackbirding trade (with adverse effects on islanders) that the British Navy sent ships from Australia Station into the Pacific to suppress the trade. (By 1808 both Great Britain and the United States had prohibited the African slave trade.) However, the ships of the Australian Squadron (HMS Basilisk, HMS Beagle, HMS Conflict, HMS Renard, HMS Sandfly and HMS Rosario) did not succeed in suppressing the blackbirding trade.

Other examples of blackbirding

United States

Since colonial times in the United States, the Reverse Underground Railroad existed to capture free African-Americans and fugitive slaves and sell them into slavery, being particularly prevalent in the 19th century after the Atlantic slave trade was outlawed. People of African and mixed ancestry commonly took part in these operations in order to make a living. Some worked under white employers, playing instrumental roles in deceiving fellow African-Americans and luring them into traps, while others pointed slave owners to the location of their escaped slaves to catch the bounty on the slave's head. The kidnappers were recorded to have acted against their own family members in addition to other members of their community. Their careers also tended to be long, due to African-Americans, particularly children, being more inclined to trust them than white people. Successful kidnappings mainly relied on the blackbirders developing a connection to their target by using their shared racial and cultural identities. New York City and Philadelphia were particularly prominent places for these kidnappers to work, causing fear of being kidnapped by anyone to become prevalent.[91]

Representation in popular culture

American author Jack London recounted in his memoir, The Cruise of the Snark (1907), an incident at Langa Langa Lagoon Malaita, Solomon Islands, when the local islanders attacked a "recruiting" ship:

... still bore the tomahawk marks where the Malaitans at Langa Langa several months before broke in for the trove of rifles and ammunition locked therein, after bloodily slaughtering Jansen's predecessor, Captain Mackenzie. The burning of the vessel was somehow prevented by the black crew, but this was so unprecedented that the owner feared some complicity between them and the attacking party. However, it could not be proved, and we sailed with the majority of this same crew. The present skipper smilingly warned us that the same tribe still required two more heads from the Minota, to square up for deaths on the Ysabel plantation. (p 387)[92]

In another passage from the same book, he wrote:

Three fruitless days were spent at Su'u. The Minota got no recruits from the bush and the bushmen got no heads from the Minota. (p 270)

See also

- Coolie

- Coolitude

- Reverse Underground Railroad, sometimes known as "blackbirding"

- Roundup (history)

- Shanghaiing

References

- ^ Emma Christopher, Cassandra Pybus and Marcus Buford Rediker (2007). Many Middle Passages: Forced Migration and the Making of the Modern World, University of California Press, pp. 188–190. ISBN 0-520-25206-3.

- ^ a b c d e Maude, H.E. (1981). Slavers in Paradise. ANU Press.

- ^ Willoughby, Emma. "Our Federation Journey 1901–2001" (PDF). Museum Victoria. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2006. Retrieved 14 June 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Reid Mortensen, (2009), "Slaving In Australian Courts: Blackbirding Cases, 1869–1871", Journal of South Pacific Law, 13:1, accessed 7 October 2010

- ^ Roberts, J. Timmons; Thanos, Nikki Demetria (2003). Trouble in Paradise: Globalization and Environmental Crises in Latin America. Routledge, London and New York. p. vii.

- ^ "EXPORTS". Sydney Chronicle. Vol. 4, , no. 370. New South Wales, Australia. 21 April 1847. p. 2. Retrieved 1 May 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Syfney News". The Port Phillip Patriot And Morning Advertiser. Vol. X, , no. 1, 446. Victoria, Australia. 1 October 1847. p. 2. Retrieved 1 May 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Shipping intelligence". The Australian. New South Wales, Australia. 22 October 1847. p. 2. Retrieved 1 May 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The South Australian Register. ADELAIDE: SATURDAY, DECEMBER 11,1847". South Australian Register. Vol. XI, , no. 790. South Australia. 11 December 1847. p. 2. Retrieved 1 May 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "THE ALLEGED MURDER AT ROTUMAH". Bell's Life In Sydney And Sporting Reviewer. Vol. IV, , no. 153. New South Wales, Australia. 1 July 1848. p. 2. Retrieved 1 May 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Murray A.W., 1876. Forty Years' Mission Work. London: Nisbet

- ^ the figure of 171 taken from Funafuti is given by Laumua Kofe, Palagi and Pastors, Tuvalu: A History, Ch. 15, Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific and Government of Tuvalu, 1983

- ^ the figure of 250 taken from Nukulaelae is given by Laumua Kofe, Palagi and Pastors, Tuvalu: A History, Ch. 15, U.S.P./Tuvalu (1983)

- ^ W.F. Newton, The Early Population of the Ellice Islands, 76(2) (1967) The Journal of the Polynesian Society, 197–204.

- ^ the figure of 250 taken from Nukulaelae is stated by Richard Bedford, Barrie Macdonald & Doug Monro, Population Estimates for Kiribati and Tuvalu (1980) 89(1) Journal of the Polynesian Society 199

- ^ a b Tracey Flanagan, Meredith Wilkie, and Susanna Iuliano. "Australian South Sea Islanders: A Century of Race Discrimination under Australian Law" Archived 14 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Human Rights Commission.

- ^ "GENERAL NEWS". The Queenslander. No. 2174. Queensland, Australia. 9 November 1907. p. 32. Retrieved 5 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Corris, Peter (13 December 2013), Passage, port and plantation: a history of Solomon Islands labour migration, 1870 - 1914, retrieved 5 July 2019

- ^ McKinnon, Alex (July 2019). "Blackbirds, Australia had a slave trade?". The Monthly. No. 157. p. 44.

- ^ Ray, K.M. "Life Expectancy and Mortality rates". Encyclopedia.com. Gale Library of Daily Life: Slavery in America. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "BRISBANE". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. XLVIII, , no. 7867. New South Wales, Australia. 22 August 1863. p. 6. Retrieved 12 May 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "THE SLAVE TRADE IN QUEENSLAND". The Courier (Brisbane). Vol. XVIII, , no. 1724. Queensland, Australia. 22 August 1863. p. 4. Retrieved 12 May 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Towns, Robert. (1863), South Sea Island immigration for cotton culture : a letter to the Hon. the Colonial Secretary of Queensland, retrieved 17 May 2019

- ^ "CLEVELAND BAY". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXI, , no. 2, 653. Queensland, Australia. 28 July 1866. p. 7. Retrieved 12 May 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "A FAIR THING FOR THE POLYNESIANS". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXV, , no. 4, 199. Queensland, Australia. 20 March 1871. p. 7. Retrieved 1 June 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "BOWEN". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXI, , no. 2, 719. Queensland, Australia. 13 October 1866. p. 6. Retrieved 12 May 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "REVIVAL OF THE SLAVE TRADE IN QUEENSLAND". The Queenslander. Vol. II, , no. 98. Queensland, Australia. 9 November 1867. p. 5. Retrieved 5 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "SOUTH SEA ISLANDS". Empire (newspaper). No. 5027. New South Wales, Australia. 31 December 1867. p. 8. Retrieved 5 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "BRISBANE". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. LVI, , no. 9202. New South Wales, Australia. 18 November 1867. p. 4. Retrieved 5 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "SLAVERY IN QUEENSLAND". Queanbeyan Age. Vol. X, , no. 394. New South Wales, Australia. 15 February 1868. p. 4. Retrieved 5 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b c Docker, Edward W. (1970). The Blackbirders. Angus and Robertson.

- ^ "THE SOUTH SEA ISLANDER TRAFFIC". The Queenslander. Vol. III, , no. 135. Queensland, Australia. 5 September 1868. p. 9. Retrieved 5 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b c James A. Michener & A. Grove Day, "Bully Hayes, South Sea Buccaneer", in Rascals in Paradise, London: Secker & Warburg 1957.

- ^ Hope, James L.A. (1872). In Quest of Coolies. London: Henry S. King & Co.

- ^ a b Palmer, George (1871). Kidnapping in the South Seas. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas.

- ^ a b Wawn, William T. (1893). The South Sea Islanders and the Queensland Labour Trade. London: Swan Sonnenschein.

- ^ "Trip of the Bobtail Nag". The Capricornian. Vol. 3, , no. 33. Queensland, Australia. 18 August 1877. p. 10. Retrieved 8 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "THE POLYNESIAN BOYS PER LYTTONA". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXVII, , no. 4, 901. Queensland, Australia. 14 June 1873. p. 6. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "REMOVAL OF SOUTH SEA ISLANDERS BY BRITISH VESSELS". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXV, , no. 4, 199. Queensland, Australia. 20 March 1871. p. 7. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "The Courier". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXVI, , no. 4, 437. Queensland, Australia. 21 December 1871. p. 2. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Tambo". The Queenslander. Vol. XI, , no. 39. Queensland, Australia. 13 May 1876. p. 3 (The Queenslander). Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "The Brisbane Courier". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXXI, , no. 2, 969. Queensland, Australia. 24 November 1876. p. 2. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "THE MURDER OF MESSRS. GIBBIE AND BELL". The Maitland Mercury And Hunter River General Advertiser. Vol. XXV, , no. 3158. New South Wales, Australia. 6 August 1868. p. 3. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "POLYNESIAN LABORERS ON NORTHERN STATIONS". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXVI, , no. 4, 307. Queensland, Australia. 22 July 1871. p. 5. Retrieved 8 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Transferring Kanakas". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXXIII, , no. 3, 751. Queensland, Australia. 27 May 1879. p. 3. Retrieved 8 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "SEIZURE OF THE WOODBINE AND CHRISTINA". The Age. No. 5689. Victoria, Australia. 20 February 1873. p. 4. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "IN THE VICE-ADMIRALTY COURT". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. LXVIII, , no. 11, 035. New South Wales, Australia. 29 September 1873. p. 2. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "LATEST INTELLIGENCE". Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald And General Advertiser. Vol. XIV, , no. 2025. Queensland, Australia. 22 May 1875. p. 3. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "MARYBOROUGH". The Telegraph. No. 987. Queensland, Australia. 30 November 1875. p. 3. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "PARLIAMENTARY PAPER". The Telegraph. No. 2, 401. Queensland, Australia. 26 July 1880. p. 3. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "THE LAST DAYS OF POLYNESIAN LABOR". The Queenslander. Vol. VII, , no. 339. Queensland, Australia. 3 August 1872. p. 3. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Correspondence". Rockhampton Bulletin. Vol. XVIII, , no. [?]402. Queensland, Australia. 4 December 1875. p. 3. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "CRUISE OF THE FLORA". The Capricornian. Vol. 1, , no. 50. Queensland, Australia. 11 December 1875. p. 799. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "QUEENSLAND". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 12, 841. New South Wales, Australia. 29 May 1879. p. 5. Retrieved 8 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "PUNISHMENT OF THE SOUTH SEA ISLAND MASSACRES". The Age. No. 7610. Victoria, Australia. 4 July 1879. p. 2. Retrieved 8 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "SOUTH SEA ISLAND OUTRAGES". The Australasian. Vol. XXIII, , no. 609. Victoria, Australia. 1 December 1877. p. 23. Retrieved 8 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "CRUISE OF THE MAY QUEEN". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXXIII, , no. 3, 599. Queensland, Australia. 29 November 1878. p. 2. Retrieved 8 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Eden, Charles H (1 January 1872), My wife and I in Queensland : an eight years' experience in the above colony, with some account of Polynesian labour, Longmans Green, retrieved 8 July 2019

- ^ "EXECUTION OF TWO SOUTH SEA ISLANDERS". Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald And General Advertiser. Vol. XVI, , no. 2249. Queensland, Australia. 24 May 1877. p. 3. Retrieved 8 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "THE RECENT OUTRAGES IN THE SOUTH SEA ISLANDS". The Sydney Daily Telegraph. No. 522. New South Wales, Australia. 4 March 1881. p. 3. Retrieved 9 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "ANOTHER SOUTH SEA MASSACRE". The Age. No. 8371. Victoria, Australia. 13 December 1881. p. 3. Retrieved 9 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "MASSACRE OF LIEUTENANT BOWER AND FIVE SEAMEN OF H.M.S. SANDFLY". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 13, 314. New South Wales, Australia. 2 December 1880. p. 7. Retrieved 9 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "MURDER IN THE SOUTH SEA ISLANDS". The Age. No. 8463. Victoria, Australia. 31 March 1882. p. 3. Retrieved 9 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "PUNISHING THE SOUTH SEA ISLANDERS". The Goulburn Herald And Chronicle. New South Wales, Australia. 2 February 1881. p. 4. Retrieved 12 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "PUNISHMENT OF THE SANDFLY MURDERERS". The Age. No. 8306. Victoria, Australia. 28 September 1881. p. 1 (Supplement to The Age). Retrieved 12 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "THE MAY QUEEN OUTRAGE". The Age. No. 8289. Victoria, Australia. 8 September 1881. p. 3. Retrieved 12 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "CRUISE OF H.M.S. DIAMOND". The Sydney Daily Telegraph. No. 986. New South Wales, Australia. 4 September 1882. p. 3. Retrieved 12 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Outrage at Ambrym". Evening News. No. 4996. New South Wales, Australia. 22 August 1883. p. 8. Retrieved 12 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "OUTRAGES IN THE SOUTH SEA ISLANDS". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXXIX, , no. 8, 387. Queensland, Australia. 26 November 1884. p. 3. Retrieved 12 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Peter Corris, 'Melvin, Joseph Dalgarno (1852–1909)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/melvin-joseph-dalgarno-7556/text13185, published first in hardcopy 1986, accessed online 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Queensland Government, Australian South Sea Islander Training Package". Archived from the original on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Documenting Democracy". Foundingdocs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Connell, John. (2010). From Blackbirds to Guestworkers in the South Pacific. Plus ça Change…? The Economic and Labour Relations Review. 20. 111-121. 10.1177/103530461002000208

- ^ Jane Resture. "The Story of Blackbirding in the South Seas – Part 2". Janesoceania.com. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ a b c R. G. Elmslie, 'The Colonial Career of James Patrick Murray', Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery, (1979) 49(1):154-62

- ^ Sydney Morning Herald, 20–23 Nov 1872, 1 March 1873

- ^ "Solomon Islands descendants win land case". Fijitimes.com. 2 February 2007. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ramsden, Eric (1946). "William Stewart and the introduction of Chinese labour in Tahiti". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 55 (3). Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ "TRAGEDY IN THE SOUTH SEAS". Evening News. No. 787. New South Wales, Australia. 8 February 1870. p. 3. Retrieved 2 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "POLYNESIAN SLAVERY". Empire (newspaper). No. 6558. New South Wales, Australia. 18 April 1873. p. 3. Retrieved 2 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "THE GERMANS IN SAMOA". The Daily Telegraph. No. 1819. New South Wales, Australia. 8 May 1885. p. 5. Retrieved 5 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "AFFAIRS IN THE NEW HEBRIDES". The Mercury. Vol. LVI, , no. 6, 401. Tasmania, Australia. 28 August 1890. p. 3. Retrieved 5 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "PRODUCTS OF SAMOA". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 23, 914. New South Wales, Australia. 1 September 1914. p. 5. Retrieved 5 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "A Murderous Madman". Newcastle Morning Herald And Miners' Advocate. Vol. VIII, , no. 1750. New South Wales, Australia. 2 February 1880. p. 2. Retrieved 5 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "AFFAIRS IN SAMOA". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 17, 508. New South Wales, Australia. 1 May 1894. p. 3. Retrieved 5 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c McCreery, David (1993). "The cargo of the Montserrat: Gilbertese labour in Guatemalan coffee". The Americas. 49 (3): 271–295. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ Kroeger, Brooke (2012). Undercover Reporting. Northwestern University Press. pp. 35–38.

- ^ "THE LOSS OF THE TAHITI". The Daily Telegraph. No. 3910. New South Wales, Australia. 7 January 1892. p. 4. Retrieved 3 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "THE LABOUR TRAFFIC IN THE SOUTH SEA ISLANDS". The West Australian. Vol. 9, , no. 2, 166. Western Australia. 20 January 1893. p. 6. Retrieved 3 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b c d Kolshus, Thorgeir; Hovdhaugen, Even (2010). "Reassessing the death of Bishop John Coleridge Patteson". The Journal of Pacific History. 45 (3): 331–355. doi:10.1080/00223344.2010.530813.

- ^ Bell, Richard. "Counterfeit Kin: Kidnappers of Color, the Reverse Underground Railroad, and the Origins of Practical Abolition". EBSCOHost.

- ^ "The Log of the Stark". Retrieved 9 April 2011.

Bibliography

- Affeldt, Stefanie. (2014). Consuming Whiteness. Australian Racism and the 'White Sugar' Campaign. Berlin [et al.]: Lit. ISBN 978-3-643-90569-7.

- Corris, Peter. (1973). Passage, Port and Plantation: A History of the Solomon Islands Labour Migration, 1870–1914. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-84050-6.

- Docker, E. W. (1981). The Blackbirders: A Brutal Story of the Kanaka Slave-Trade. London: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0-207-14069-3

- Gravelle, Kim. (1979). A History of Fiji. Suva: Fiji Times Limited.

- Horne, Gerald. (2007). The White Pacific: US Imperialism and Black Slavery in the South Seas after the Civil War. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3147-9

- Maude, H. E. (1981). Slavers in Paradise: The Peruvian Slave Trade in Polynesia, 1862-1864 Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies. ASIN B01HC0W8FU

- Shineberg, Dorothy (1999) The People Trade: Pacific Island Labourers and New Caledonia, 1865-1930 (Pacific Islands Monographs Series) ISBN 978-0824821777

External links

- Background and history of the South Sea Islanders – Queensland Department of Premier and Cabinet

- Jane Resture, The Kanakas and the Cane Fields