Impeachment in the United States: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

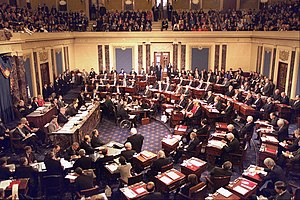

[[Image:Senate in session.jpg|thumb|300px|The [[Impeachment of Bill Clinton|impeachment trial of President Bill Clinton]] in 1999, [[William H. Rehnquist|Chief Justice William Rehnquist]] presiding. The House managers are seated beside the quarter-circular tables on the left and the president's personal counsel on the right, much in the fashion of President Andrew Johnson's trial.]] |

[[Image:Senate in session.jpg|thumb|300px|The [[Impeachment of Bill Clinton|impeachment trial of President Bill Clinton]] in 1999, [[William H. Rehnquist|Chief Justice William Rehnquist]] presiding. The House managers are seated beside the quarter-circular tables on the left and the president's personal counsel on the right, much in the fashion of President Andrew Johnson's trial.]] |

||

'''Impeachment in the United States''' is an expressed power of the [[United States Congress|legislature]] that allows for formal charges against a civil officer of government for crimes committed in office. The actual trial on those charges, and subsequent removal of an official on [[conviction]] on those charges, is separate from the act of [[impeachment]] itself |

'''Impeachment in the United States''' is an expressed power of the [[United States Congress|legislature]] that allows for formal charges '''against a civil officer of government for''' crimes committed in office. The actual trial on those charges, and subsequent removal of an official on [[conviction]] on those charges, is separate from the act of [[impeachment]] '''itself'''''''''Bold text'''''''''Bold text''''''Bold text''''''''' |

||

Impeachment is analogous to [[indictment]] in regular court proceedings, while trial by the other house is analogous to the [[trial]] before [[judge]] and [[jury]] in regular courts. Typically, the [[lower house]] of the legislature will impeach the official and the [[upper house]] will conduct the trial. |

Impeachment is analogous to [[indictment]] in regular court proceedings, while trial by the other house is analogous to the [[trial]] before [[judge]] and [[jury]] in regular courts. Typically, the [[lower house]] of the legislature will impeach the official and the [[upper house]] will conduct the trial. |

||

Revision as of 13:41, 17 March 2010

Impeachment in the United States is an expressed power of the legislature that allows for formal charges against a civil officer of government for crimes committed in office. The actual trial on those charges, and subsequent removal of an official on conviction on those charges, is separate from the act of impeachment itself''''Bold text''''Bold text'Bold text''''

Impeachment is analogous to indictment in regular court proceedings, while trial by the other house is analogous to the trial before judge and jury in regular courts. Typically, the lower house of the legislature will impeach the official and the upper house will conduct the trial.

At the federal level, Article Two of the United States Constitution (Section 4) states that "The President, Vice President, and all other civil Officers of the United States shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other High Crimes and Misdemeanors." The House of Representatives has the sole power of impeaching, while the United States Senate has the sole power to try all impeachments. The removal of impeached officials is automatic upon conviction in the Senate.

Impeachment can also occur at the state level; state legislatures can impeach state officials, including governors, according to their respective state constitutions.

The federal impeachment procedure

The House of Representatives

Impeachment proceedings may be commenced by a member of the House of Representatives on their own initiative, either by presenting a listing of the charges under oath, or by asking for referral to the appropriate committee. The impeachment process may be triggered by non-members. For example, when the Judicial Conference of the United States suggests a federal judge be impeached, a charge of what actions constitute grounds for impeachment may come from a special prosecutor, the President, a state or territorial legislature, grand jury, or by petition.

The type of impeachment resolution determines which committee it will be referred to. A resolution impeaching a particular individual is typically referred to the House Committee on the Judiciary. A resolution to authorize an investigation regarding impeachable conduct is referred to the House Committee on Rules, and then referred to the Judiciary Committee. The House Committee on the Judiciary, by majority vote, will determine whether grounds for impeachment exist. If the Committee finds grounds for impeachment they will set forth specific allegations of misconduct in one or more "articles of impeachment." The Impeachment Resolution, or Article(s) of Impeachment, are then reported to the full House with the committee's recommendations.

The House debates the resolution and may at the conclusion consider the resolution as a whole or vote on each article of impeachment individually. A simple majority of those present and voting is required for each article or the resolution as a whole to pass. If the House votes to impeach, managers are selected to present the case to the Senate. Recently, managers have been selected by resolution, while historically the House would occasionally elect the managers or pass a resolution allowing the appointment of managers at the discretion of the Speaker of the House of Representatives.

Also, the House will adopt a resolution in order to notify the Senate of its action. After receiving the notice, the Senate will adopt an order notifying the House that it is ready to receive the managers. The House managers then appear before the bar of the Senate and exhibit the articles of impeachment. After the reading of the charges, the managers return and make a verbal report to the House.

Senate

The proceedings unfold in the form of a trial, with each side having the right to call witnesses and perform cross-examinations. The House members, who are given the collective title "managers" during the course of the trial, present the prosecution case and the impeached official has the right to mount a defense with his own attorneys as well. Senators must also take an oath or affirmation that they will perform their duties honestly and with due diligence (as opposed to the House of Lords in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, who vote upon their honor). After hearing the charges, the Senate usually deliberates in private. Conviction requires a two-thirds majority.

The Senate enters judgment on its decision, whether that be to convict or acquit, and a copy of the judgment is filed with the Secretary of State.[1] Upon conviction, the official is automatically removed from office and may also be barred from holding future office. The removed official is also liable to criminal prosecution. The President may not grant a pardon in the impeachment case, but may in any resulting criminal case.

Beginning in the 1980s, the Senate began using "Impeachment Trial Committees" pursuant to Senate Rule XII. These committees presided over the evidentiary phase of the trials, hearing the evidence and supervising the examination and cross-examination of witnesses. The committees would then compile the evidentiary record and present it to the Senate; all senators would then have the opportunity to review the evidence before the chamber voted to convict or acquit. The purpose of the committees was to streamline impeachment trials, which otherwise would have taken up a great deal of the chamber's time. Defendants challenged the use of these committees, claiming them to be a violation of their fair trial rights as well as the Senate's constitutional mandate, as a body, to have "sole power to try all impeachments." Several impeached judges sought court intervention in their impeachment proceedings on these grounds, but the courts refused to become involved due to the Constitution's granting of impeachment and removal power solely to the legislative branch, making it a political question.

History

In writing Article II, Section Four, George Mason had favored impeachment for "maladministration" (incompetence), but James Madison, who favored impeachment only for criminal behavior, carried the issue.[2] Hence, cases of impeachment may be undertaken only for "treason, bribery and other high crimes and misdemeanors." However, some scholars, such as Kevin Gutzman, have disputed this view and argue that the phrase "high crimes and misdemeanors" was intended to have a much more expansive meaning (see, for example, Kevin Gutzman's The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Constitution, which has an extensive discussion of this question).

The Congress traditionally regards impeachment as a power to use only in extreme cases; the House of Representatives has actually initiated impeachment proceedings only 62 times since 1789. Two cases did not come to trial because the individuals had left office.

Actual impeachments of 19 federal officers have taken place. Of these, 15 were federal judges: Twelve district court, two court of appeals (one of whom also sat on the Commerce Court), and one Supreme Court Associate Justice. Of the other four, two were Presidents, one was a Cabinet secretary, and one was a U.S. Senator. Of the 18 impeached officials, seven were convicted. One, former judge Alcee Hastings, was elected as a member of the United States House of Representatives after being removed from office.

The 1797 impeachment of Senator William Blount of Tennessee stalled on the grounds that the Senate lacked jurisdiction over him. Because, in a separate action unrelated to the impeachment procedure, the Senate had already expelled Blount, the lack of jurisdiction may have been either because Blount was no longer a Senator, or because Senators are not "civil officers" of the federal government and therefore not subject to impeachment. No other member of Congress has ever been impeached, although the Constitution does give authority to either house to expel members, which each has done on occasion, removing the individual from functioning as a representative or senator for misbehavior. Expulsion, unlike impeachment, cannot bar an individual from holding future office.

Impeachment of a U.S. President

Two U.S. Presidents have been impeached: Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton. Both were acquitted at trial. Richard Nixon resigned in the face of the near certainty of his impeachment, which had already been approved by the House Judiciary Committee.

The Chief Justice of the United States presides during the Senate trial of a President.[3]

Federal officials impeached

| # | Date of Impeachment | Accused | Office | Result[Note 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | July 7, 1797[4] | William Blount | United States Senator (Tennessee) | Dismissed on January 14, 1799[5][Note 2] |

| 2 | March 2, 1803[4][6] | John Pickering | Judge (District of New Hampshire) | Removed on March 12, 1804[5][6] |

| 3 | March 12, 1804[4][6] | Samuel Chase | Associate Justice (Supreme Court of the United States) | Acquitted on March 1, 1805[5][6] |

| 4 | April 24, 1830[4][6] | James H. Peck | Judge (District of Missouri) | Acquitted on January 31, 1831[5][6] |

| 5 | May 6, 1862[4][6] | West Hughes Humphreys | Judge (Eastern, Middle, and Western Districts of Tennessee) | Removed and disqualified on June 26, 1862[4][5][6] |

| 6 | February 24, 1868[4] | Andrew Johnson | President of the United States | Acquitted on May 26, 1868[5] |

| 7 | February 28, 1873[7][6] | Mark W. Delahay | Judge (District of Kansas) | Resigned on December 12, 1873[7][6] |

| 8 | March 2, 1876[4] | William W. Belknap | United States Secretary of War | Acquitted after his resignation on August 1, 1876.[5] |

| 9 | December 13, 1904[4][6] | Charles Swayne | Judge (Northern District of Florida) | Acquitted on February 27, 1905[5][6] |

| 10 | July 11, 1912[4][6] | Robert W. Archbald | Associate Justice (United States Commerce Court) Judge (Third Circuit Court of Appeals) |

Removed and disqualified on January 13, 1913[5][6][4] |

| 11 | April 1, 1926[4][6] | George W. English | Judge (Eastern District of Illinois) | Resigned on November 4, 1926,[5][4] proceedings dismissed on December 13, 1926[6][4] |

| 12 | February 24, 1933[4][6] | Harold Louderback | Judge (Northern District of California) | Acquitted on May 24, 1933[5][6] |

| 13 | March 2, 1936[4][6] | Halsted L. Ritter | Judge (Southern District of Florida) | Removed on April 17, 1936[5][6] |

| 14 | July 22, 1986[4][6] | Harry E. Claiborne | Judge (District of Nevada) | Removed on October 9, 1986[5][6] |

| 15 | August 3, 1988[4][6] | Alcee Hastings | Judge (Southern District of Florida) | Removed on October 20, 1989[5][6] |

| 16 | May 10, 1989[4][6] | Walter Nixon | Chief Judge (Southern District of Mississippi) | Removed on November 3, 1989[5][6][Note 3] |

| 17 | December 19, 1998[4] | Bill Clinton | President of the United States | Acquitted on February 12, 1999[5][Note 4] |

| 18 | June 19, 2009[15][6] | Samuel B. Kent | Judge (Southern District of Texas) | Resigned on June 30, 2009[16][6], proceedings dismissed on July 22, 2009[17][6][5] |

| 19 | March 11, 2010[18] | Thomas Porteous | Judge (Eastern District of Louisiana) | Impeached[18]; trial pending in the Senate |

Notes

- ^ "Removed and disqualified" indicates that following conviction the Senate voted to disqualify the individual from holding further federal office pursuant to Article I, Section 3 of the United States Constitution, which provides, in pertinent part, that "[j]udgment in cases of impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust or profit under the United States."

- ^ During the impeachment trial of Senator Blount, it was argued that the House of Representatives did not have the power to impeach members of either House of Congress; though the Senate never explicitly ruled on this argument, the House has never again impeached a member of Congress. The Constitution allows either House to expel one of its members by a two-thirds vote, which the Senate had done to Blount on the same day the House impeached him (but before the Senate heard the case).

- ^ Judge Nixon later challenged the validity of his removal from office on procedural grounds; the challenge was ultimately rejected as nonjusticiable by the Supreme Court in Nixon v. United States, 506 U.S. 224 (1993).

- ^ The House of Representatives impeached President Clinton on December 19, 1998, on grounds of perjury to a grand jury (voting 228-206)[8] and obstruction of justice (221-212).[9] Two other articles of impeachment failed — a second count of perjury in the Paula Jones case (205-229)[10], and one accusing Clinton of abuse of power (148-285).[11] The Senate impeachment trial lasted from January 7, 1999, until February 12.[4] No witnesses were called during the trial, although three individuals (Monica Lewinsky, Sidney Blumenthal (a senior aide to President Clinton) and Vernon Jordan (Democratic power broker and confidant of President Clinton)) testified via videotape.[12] A two-thirds majority, 67 votes, would have been necessary to remove the President from office.[3] Both charges were defeated: perjury (45–55)[13] and obstruction of justice (50–50).[14]

Demands for impeachment

While actually impeaching a federal public official is a rare event, demands for impeachment, especially of presidents, are extremely common,[19][20] going back to the administration of George Washington in the mid-1790s. In fact, most of the 63 resolutions mentioned above were in response to presidential actions.

While almost all of them were for the most part frivolous and were buried as soon as they were introduced, several did have their intended effect. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon[21] and Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas both resigned in response to the threat of impeachment hearings, and, most famously, President Richard Nixon resigned from office after the House Judiciary Committee had already reported articles of impeachment to the floor.

Impeachment in the states

State legislatures can impeach state officials, including governors. The court for the trial of impeachments may differ somewhat from the federal model — in New York, for instance, the Assembly (lower house) impeaches, and the State Senate tries the case, but the members of the seven-judge New York State Court of Appeals (the state's highest, constitutional court) sit with the senators as jurors as well [22]. Impeachment and removal of governors has happened occasionally throughout the history of the United States, usually for corruption charges. A total of at least eleven U.S. state governors have faced an impeachment trial; a twelfth, Governor Lee Cruce of Oklahoma, escaped impeachment conviction by a single vote in 1912. Several others, most recently Connecticut's John G. Rowland, have resigned rather than face impeachment, when events seemed to make it inevitable.[23] The most recent impeachment of a governor occurred on January 14, 2009, when the Illinois House of Representatives voted 117-1 to impeach Rod Blagojevich on corruption charges;[24] he was subsequently the removed from office and barred from holding future office by the Illinois Senate on January 29. He was the eighth state governor in American history to be removed from office.

The procedure for impeachment, or removal, of local officials varies widely. For instance, in New York a mayor is removed directly by the governor "upon being heard" on charges — the law makes no further specification of what charges are necessary or what the governor must find in order to remove a mayor.

State officials impeached

See also

- Impeachment investigations of United States federal officials

- Impeachment investigations of federal judges

- Censure in the United States

- Jefferson's Manual

References

- United States Embassy Bogota, Colombia - "An Overview of the Impeachment Process"

- Jefferson's manual for impeachment

- ^ Rules of Procedure and Practice in the Senate When Sitting on Impeachment Trials

- ^ Welcome to The American Presidency

- ^ a b The Constitution of the United States, Article 1, Section 3. "The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two thirds of the Members present."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u U.S. Joint Committee on Printing (September 2006). "Impeachment Proceedings". Congressional Directory. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/5hgfBLQ9j) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Staff (n.d.). "Chapter 4: Complete List of Senate Impeachment Trials". United States Senate. Retrieved 2010-02-14.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/5nXB3Jv5H) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac staff (n.d.). "Impeachments of Federal Judges". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved 2010-02-14.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/5nXBBUy3T) - ^ a b staff (n.d.). "Judges of the United States Courts - Delahay, Mark W." Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Miller, Lorraine C. (1998-12-19). "FINAL VOTE RESULTS FOR ROLL CALL 543". Office of the Clerk. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Miller, Lorraine C. (1998-12-19). "FINAL VOTE RESULTS FOR ROLL CALL 545". Office of the Clerk. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Miller, Lorraine C. (1998-12-19). "FINAL VOTE RESULTS FOR ROLL CALL 544". Office of the Clerk. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Miller, Lorraine C. (1998-12-19). "FINAL VOTE RESULTS FOR ROLL CALL 546". Office of the Clerk. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Linder, Douglas O. (1995–2007). "The Impeachment of President Clinton: A Chronology". Famous Trials. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Senate LIS (1999-02-12). "U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 106th Congress - 1st Session: vote number 17 - Guilty or Not Guilty (Art I, Articles of Impeachment v. President W. J. Clinton )". United States Senate. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Senate LIS (1999-02-12). "U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 106th Congress - 1st Session: vote number 18 - Guilty or Not Guilty (Art II, Articles of Impeachment v. President W. J. Clinton )". United States Senate. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Powell, Stewart (2009-06-19). "U.S. House impeaches Kent". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

In action so rare it has been carried out only 14 times since 1803, the House on Friday impeached a federal judge — imprisoned U.S. District Court Judge Samuel B. Kent...

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/5hfRJRw37) - ^ Gamboa, Suzanne (2009-06-30). "White House accepts convicted judge's resignation". AP. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/5iTDSpUiA) - ^ Gamboa, Suzanne (2009-07-22). "Congress ends jailed judge's impeachment". AP. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/5iTE2kciQ) - ^ a b Alpert, Bruce (2010-03-11). "Judge Thomas Porteous impeached by U.S. House of Representatives". New Orleans Times-Picayune. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Tentative description of a dinner given to promote the impeachment of President Dwight Eisenhower: [poem] by Lawrence Ferlinghetti; City Lights Books: (1958)

- ^ Clark, Richard C. (2008-07-22). "McFadden's Attempts to Abolish the Federal Reserve System". Scribd. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

Though a Republican, he moved to impeach President Herbert Hoover in 1932 and introduced a resolution to bring conspiracy charges against the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,742975,00.html

- ^ NYS Constitution, Article VI, §24

- ^ Yardley, William (2004-06-21). "Connecticut Governor Announces His Resignation". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "House votes to impeach Blagojevich again". Chicago Tribune. 2009-01-14. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ^ Bateman, Newton (1908). Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois. Chicago, IL: Munsell Publishing Company. p. 489.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Impeachment of State Officials". Cga.ct.gov. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ a b Blackmar, Frank (1912). Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History. Standard Publishing Co. p. 598.

- ^ "State Governors of Louisiana: Henry Clay Warmoth". Enlou.com. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ "SULZER IMPEACHED BY ASSEMBLY BUT REFUSES TO SURRENDER OFFICE", Syracuse Herald, August 13, 1913, p1

- ^ "HIGH COURT REMOVES SULZER FROM OFFICE BY A VOTE OF 43 TO 12", Syracuse Herald, October 17, 1913, p1

- ^ Block, Lourenda (2000). "Permanent University Fund: Investing in the Future of Texas". TxTell (University of Texas at Austin). Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ^ Official Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Louisiana, April 6, 1929 pp. 292-94

- ^ Gruson, Lindsey (1988-02-06). "House Impeaches Arizona Governor". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Gruson, Lindsey (1988-04-05). "Arizona's Senate Ousts Governor, Voting Him Guilty of Misconduct". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Staff reporter (1989-03-30). "Impeachment in West Virginia". AP. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Wallace, Anise C. (1989-07-10). "Treasurer of West Virginia Retires Over Fund's Losses". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Hinds, Michael deCourcy (1994-05-25). "Pennsylvania House Votes To Impeach a State Justice". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

A State Supreme Court justice convicted on drug charges was impeached today by the Pennsylvania House of Representatives.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Moushey, Bill (2002-07-26). "Larsen Removed Senate Convicts Judge On 1 Charge". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, PA USA. p. A1.

Rolf Larsen yesterday became the first justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to be removed from office through impeachment. The state Senate, after six hours of debate, found Larsen guilty of one of seven articles of impeachment at about 8:25 p.m, then unanimously voted to remove him permanently from office and bar him from ever seeking an elected position again.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Young, Virginia (1994-10-07). "Moriarty Is Impeached - Secretary Of State Will Fight Removal". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, MO USA. p. 1A.

The House voted overwhelmingly Thursday to impeach Secretary of State Judith K. Moriarty for misconduct that "breached the public trust." The move, the first impeachment in Missouri in 26 years, came at 4:25 p.m. in a hushed House chamber.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Young, Virginia (1994-12-13). "High Court Ousts Moriarty". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, MO USA. p. 1A.

In a unanimous opinion Monday, the Missouri Supreme Court convicted Secretary of State Judith K. Moriarty of misconduct and removed her from office.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Vogel, Ed (2004-11-12). "Augustine impeached". Review-Journal. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Whaley, Sean (2004-12-05). "Senate lets controller keep job". Review-Journal. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Staff reporter (2009-01-09). "Illinois House impeaches Gov. Rod Blagojevich". AP. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mckinney, Dave (2009-01-14). "Illinois House impeaches Gov. Rod Blagojevich". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Long, Ray (2009-01-30). "Blagojevich is removed from office". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)