Barbary pirates: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 376959357 by 89.241.96.68 (talk) |

No sources |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

====Galley slaves==== |

====Galley slaves==== |

||

Although the conditions in bagnios were harsh, they were nothing compared to what [[galley]] slaves had to go through. A galley is a ship that could be propelled solely by human power, and that is exactly what Barbary pirates had the slaves do. Barbary galleys were at sea for around eighty to a hundred days a year, so the slaves were not on them constantly, but when they were not rowing the galleys they were forced to do difficult manual labor on land. However, there were some exceptions; "galley slaves of the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul would be permanently confined to their galleys, and often served extremely long terms, averaging around nineteen years in the late seventeenth-century and early eighteenth-century periods. And these slaves simply rarely got off the galley but lived there for years."<ref>{{cite book|last=Ekin|first=Des|title=The Stolen Village - Baltimore and the Barbary Pirates |year=2006|publisher=OBrien|isbn=9780862789558|pages=187}}</ref> During this time, rowers were shackled and chained where they sat, and were never allowed to leave. Sleeping (which was limited), eating, defecation and urination took place at the seat to which they were shackled. There was normally around five or six rowers on each oar, but this did not mean that any of the slaves could get away with any lack of effort. Overseers would walk back and forth and whip the slaves who were not rowing up to par. |

Although the conditions in bagnios were harsh, they were nothing compared to what [[galley]] slaves had to go through. A galley is a ship that could be propelled solely by human power, and that is exactly what Barbary pirates had the slaves do. Barbary galleys were at sea for around eighty to a hundred days a year, so the slaves were not on them constantly, but when they were not rowing the galleys they were forced to do difficult manual labor on land. However, there were some exceptions; "galley slaves of the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul would be permanently confined to their galleys, and often served extremely long terms, averaging around nineteen years in the late seventeenth-century and early eighteenth-century periods. And these slaves simply rarely got off the galley but lived there for years."<ref>{{cite book|last=Ekin|first=Des|title=The Stolen Village - Baltimore and the Barbary Pirates |year=2006|publisher=OBrien|isbn=9780862789558|pages=187}}</ref> During this time, rowers were shackled and chained where they sat, and were never allowed to leave. Sleeping (which was limited), eating, defecation and urination took place at the seat to which they were shackled. There was normally around five or six rowers on each oar, but this did not mean that any of the slaves could get away with any lack of effort. Overseers would walk back and forth and whip the slaves who were not rowing up to par. |

||

Yet, there were some benefits to being a galley slave. Galley slaves were entitled to a cut of the treasure if the ship was lucky enough to obtain any, this was paid to their masters who were likely to give a percentage of the slave. Also, for the slaves who managed to survive long enough, there was a possibility to being promoted onboard to positions such as a scrivani or a vagovan. A scrivani was, "a slave secretary who kept track of the lives of the slaves, and kept the financial books of the voyage." Vagovans were, "slaves who were the pace setters and organizers of the rowers." |

|||

====Freedom for slaves==== |

====Freedom for slaves==== |

||

Revision as of 16:29, 3 August 2010

The Barbary Corsairs, sometimes called Ottoman Corsairs or Barbary Pirates, were an alliance of Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa from the time of the Crusades (11th century) until the early 19th century. Based in North African ports such as Tunis, Tripoli, Algiers, Salé, and other ports in Morocco, they sailed mainly along the stretch of northern Africa known as the Barbary Coast.[1] Their predation extended throughout the Mediterranean, south along West Africa's Atlantic seaboard, and into the North Atlantic as far north as Iceland, and they primarily commandeered western European ships in the western Mediterranean Sea. In addition, they engaged in Razzias, raids on European coastal towns, to capture Christian slaves to sell at slave markets in places such as Algeria and Morocco.[2][3]

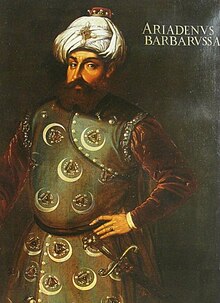

Pirates destroyed thousands of French, Spanish, Italian and British ships, and long stretches of coast in Spain and Italy were almost completely abandoned by their inhabitants, discouraging settlement until the 19th century. From the 16th to 19th century, pirates captured an estimated 800,000 to 1.25 million Europeans as slaves,[2] mainly from seaside villages in Italy, Spain, and Portugal, but also from France, Britain, the Netherlands, Ireland and as far away as Iceland. The most famous corsairs were the brothers Hayreddin Barbarossa ("Redbeard") and Oruç Reis, who took control of Algiers in the early 16th century, beginning four hundred years of Ottoman Empire presence in North Africa and establishing a centre of Mediterranean piracy.

Following the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as well as the involvement of the United States Navy in the First and Second Barbary Wars interceding to protect US interests (1801–5, 1815), European powers agreed upon the need to suppress the Barbary pirates and the effectiveness of the corsairs declined. In 1816 a joint Dutch and British Fleet under Lord Exmouth bombarded Algiers and forced that city and terrified Tunis into giving up over 3,000 prisoners and making fresh promises. Following a resumption of piracy based out of Algiers, in 1824 another British fleet again bombarded Algiers. France colonized much of the Barbary coast in the 19th century.

History

Although piracy had existed in the region throughout the decline of the Roman Empire, the barbarian invasions, and the Middle Ages, piracy became particularly flagrant in the 14th century due to the flourishing of the Mediterranean trade. The town of Bougie was then the most notorious pirate base.

For two centuries the seamanship of the Barbary Corsairs was as renowned as their cruelty. They gained their advantage from the use of oars, and their ships could sail much closer to a headwind than could European square-riggers, with oars and a sail arrangement that facilitated rapid turning.[4]

After Spain conquered Granada and expelled the Moors in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, many Muslims from Spain emigrated to the coastal cities of North Africa. Under the tutelage of first the Islamic Mamelukes of Egypt and later the Muslim Ottomans, they, together with local Berber tribes, mounted expeditions called razzias to disrupt Christian sovereigns. Under the power of the Ottomans in the 16th century, who organized the privateers, the Barbary pirates became most powerful in the 17th century. They declined in the face of European power throughout the 18th century and were finally extinguished about 1830, when the French conquered Algiers.

9th-13th centuries

Toward the end of the 9th century, Muslim pirate havens were established along the coast of southern France and northern Italy.[5] In 846 Muslim raiders sacked Rome and damaged the Vatican. In 911, the bishop of Narbonne was unable to return to France from Rome because the Muslims controlled all the passes in the Alps.

With the decline of the Eastern Roman Empire and the rise of Islamic power in the eastern Mediterranean, piracy spread further, with Muslim pirates occupying Cyprus, Crete, and Sicily in the 9th century, and entering southern Italy.[6] Muslim pirates operated out of the Balearic Islands in the 10th century. From 824 to 961 Arab pirates in Crete raided the entire Mediterranean.

Piracy increased in the 13th century as the Byzantine Empire collapsed.

14th-16th centuries

In the 14th century, raids by Muslim pirates forced the Venetian Duke of Crete to ask Venice to keep its fleet on constant guard.[7]

The conquest of Granada by the Catholic sovereigns of Spain in 1492 drove many Moors into exile. They retaliated by piratical attacks on the Spanish coast, with help from Muslim adventurers from the Levant, of whom the most successful were Hızır and Oruç, natives of Mitylene. In response, Spain began to conquer the coast towns of Oran, Algiers and Tunis. But after Oruç was killed in battle with the Spaniards in 1518, his brother Hızır appealed to Selim I, the Ottoman Sultan, who sent him troops. In 1529, Hızır drove the Spaniards from the rocky, fortified island in front of Algiers, and founded the Ottoman power in the region. From about 1518 till the death of Uluch Ali in 1587, Algiers was the main seat of government of the beylerbeys of northern Africa, who ruled over Tripoli, Tunisia and Algeria. From 1587 to 1659, they were ruled by Ottoman pashas, sent from Constantinople to govern for three years; but in the latter year a military revolt in Algiers reduced the pashas to nonentities. From 1659, these African cities, although nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, were in fact military republics which chose their own rulers and lived by plunder.

During the first period (1518–1587), the beylerbeys were admirals of the sultan, commanding great fleets and conducting war operations for political ends. They were slave-hunters and their methods were ferocious. After 1587, the sole object of their successors became plunder, on land and sea. The maritime operations were conducted by the captains, or reises, who formed a class or even a corporation. Cruisers were fitted out by capitalists and commanded by the reises. Ten percent of the value of the prizes was paid to the pasha or his successors, who bore the titles of agha or dey or bey.[8]

In 1544, Hayreddin captured the island of Ischia, taking 4,000 prisoners, and enslaved some 9,000 inhabitants of Lipari, almost the entire population.[9] In 1551, Turgut Reis enslaved the entire population of the Maltese island Gozo, between 5,000 and 6,000, sending them to Libya. In 1554, pirates sacked Vieste in southern Italy and took an estimated 7,000 slaves.[10] In 1555, Turgut Reis sacked Bastia, Corsica, taking 6,000 prisoners. In 1558, Barbary corsairs captured the town of Ciutadella (Minorca), destroyed it, slaughtered the inhabitants and took 3,000 survivors to Istanbul as slaves.[11] In 1563, Turgut Reis landed on the shores of the province of Granada, Spain, and captured coastal settlements in the area, such as Almuñécar, along with 4,000 prisoners. Barbary pirates often attacked the Balearic Islands, and in response many coastal watchtowers and fortified churches were erected. The threat was so severe that the island of Formentera became uninhabited.[12][13]

Even at this early stage, the European states fought back: Livorno's monument Quattro Mori celebrates 16th century victories against the Barbary corsairs won by the Knights of Malta and the Order of Saint Stephen, of which the Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinando I de' Medici was Grand Master. Another response was the construction of the original frigates; light, fast and manoueverable galleys, designed to run down Barbary pirates trying to get away with their loot and slaves. Other measures included coastal lookouts to give warning for people to withdraw into fortified places and rally local forces to fight the pirates, though this latter objective was especially difficult to achieve as the pirates had the advantage of surprise; the vulnerable European Mediterranean coasts were very long and easily accessible from the north African Barbary bases, and the pirates were careful in planning their raids.

17th century

Later, in 1607, the Order of Malta went on the offensive with forty-five galleys, capturing and pillaging the city of Bona in Algeria.[14] This victory is commemorated by a series of frescoes painted by Bernardino Poccetti in the "Sala di Bona" of Palazzo Pitti, Florence.[15]

From 1609 to 1616, England lost 466 merchant ships to Barbary pirates. 160 British ships were captured by Algerians between 1677 and 1680.[16] Later, American ships were also attacked. During this period, the pirates forged affiliations with Caribbean powers, paying a "license tax" in exchange for safe harbor of their vessels.[17]

Some pirates were renegades or moriscos. They usually used galley ships with slaves or prisoners at the oars. Two examples are Süleyman Reis, "De Veenboer", who became admiral of the Algerian corsair fleet in 1617, and his quartermaster Murat Reis, born Jan Janszoon. Both worked for the notorious corsair Zymen Danseker, who owned a palace. These pirates were all originally Dutch. The Dutch admiral Michiel de Ruyter unsuccessfully tried to end their piracy.

The first half of the 17th century may be described as the flowering time of the Barbary pirates. This was due largely to the efforts of Simon de Danser, who had introduced the latest Dutch sailing rigs to the corsairs, enabling them to brave Atlantic waters.[18] More than 20,000 captives were said to be imprisoned in Algiers alone. The rich were allowed to redeem themselves, but the poor were condemned to slavery. Their masters would on occasion allow them to secure freedom by professing Islam. A long list might be given of people of good social position, not only Italians or Spaniards, but German or English travelers in the south, who were captives for a time.[8]

Iceland was subject to raids known as the Turkish abductions in 1627. Jan Janszoon, (Murat Reis the Younger) is said to have taken 400 prisoners; 242 of the captives later were sold into slavery on the Barbary Coast. The pirates took only young people and those in good physical condition. All those offering resistance were killed, and the old people were gathered into a church which was set on fire. Among those captured was Ólafur Egilsson, who was ransomed the next year and, upon returning to Iceland, wrote a slave narrative about his experience. Another famous captive from that raid was Guðríður Símonardóttir. The sack of Vestmannaeyjar is known in the history of Iceland as Tyrkjaránið and is arguably the most horrible event in the history of Vestmannaeyjar.

Ireland was subject to a similar attack. In June 1631 Murat Reis, with pirates from Algiers and armed troops of the Ottoman Empire, stormed ashore at the little harbor village of Baltimore, County Cork. They captured almost all the villagers and took them away to a life of slavery in North Africa.[8] The prisoners were destined for a variety of fates — some lived out their days chained to the oars as galley slaves, while others would spend long years in the scented seclusion of the harem or within the walls of the sultan's palace. The old city of Algiers, with its narrow streets, intense heat and lively trade, was a melting pot where the villagers would join slaves and freemen of many nationalities. Only two of them ever saw Ireland again.[19]

Barbary pirate attacks were common in southern Portugal, south and east Spain, the Balearic Islands, Sardinia, Corsica, Elba, the Italian Peninsula (especially the coasts of Liguria, Tuscany, Lazio, Campania, Calabria and Apulia), Sicily and Malta. They also occurred on the Atlantic northwest coast of the Iberian Peninsula. In 1617, the African corsairs launched their major attack in the region when they destroyed and sacked Bouzas, Cangas and the churches of Moaña and Darbo.

The chief victims were the inhabitants of the coasts of Sicily, Naples and Spain. But all traders of nations which did not pay tribute for immunity were liable to be taken at sea. This tribute, disguised as presents or ransoms, did not always ensure safety. The most powerful states in Europe condescended to pay the pirates and tolerate their insults. Religious orders — the Redemptorists and Lazarists — worked for the redemption of captives, and large legacies were left for that purpose in many countries.

The continued piracy was due to competition among European powers. France encouraged the pirates against Spain, and later Britain and Holland supported them against France. In the 18th century, British public men were not ashamed to say that Barbary piracy was a useful check on the competition of the weaker Mediterranean nations in the carrying trade.[20] Every power wanted to secure immunity for itself and was more or less ready to compel Tripoli, Tunis, Algiers, Sale and the rest to respect only its own trade and subjects. In 1655, British admiral Robert Blake was sent to punish the Tunisians, and he gave them a severe beating. During the reign of Charles II, the British fleet made many expeditions, sometimes together with the Dutch. In 1675 a Royal Navy squadron led by Sir John Narborough was sent to suppress piracies, and bombarded Tripoli. In 1682 and 1683, the French bombarded Algiers. On the second occasion the Algerines blew the French consul from a gun during the action.

18th century

In 1783 and 1784 it was the turn of Spaniards to bombard Algiers. The second time, admiral Barceló damaged the city so severely that the Algerian Dey asked Spain to negotiate a peace treaty and from then on Spanish vessels and coasts were safe for several years.

Such punitive expeditions were never pushed home, and the aggrieved European state almost always agreed in the end to pay money to secure peace. The frequent wars among European states gave the pirates many opportunities of breaking their engagements, and they always took advantage of that.[8]

Until the Declaration of Independence in 1776 British treaties with the North African states of Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli protected American ships from the Barbary corsairs. Morocco, which in 1777 was the first independent nation to publicly recognize the United States, became in 1784 the first Barbary power to seize an American vessel after independence. That action got the attention the sultan sought; it followed several years of fruitless diplomatic efforts to get an American emissary to come negotiate a treaty. Thomas Barclay, American consul in France, went to Morocco in 1786 and negotiated a very satisfactory treaty based on the draft he had carried from Paris and requiring no future tribute or gifts.[21] Experience with Algiers was different. In 1785 two ships (the Maria of Boston and the Dauphin of Philadelphia) were seized, the ships and cargo were sold and the crews were enslaved and held for ransom.[22]

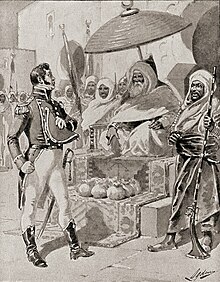

In 1786, Thomas Jefferson, then the ambassador to France, and John Adams, ambassador to Britain, met in London with Sidi Haji Abdul Rahman Adja, a visiting ambassador from Tripoli. The Americans asked Adja why his government was hostile to American ships, even though there had been no provocation. They reported to the Continental Congress that the ambassador had told them "it was written in their Koran, that all nations which had not acknowledged the Prophet were sinners, whom it was the right and duty of the faithful to plunder and enslave," but he also told them that for what they considered outrageous sums of money they could make peace.[23]

American ships sailing in the Mediterranean chose to travel close to larger convoys of other European powers who had paid tribute to the pirates. Payments in ransom and tribute to the Barbary states amounted to 20% of United States government annual expenditures in 1800.[24] In the early nineteenth century, President Thomas Jefferson proposed a league of smaller nations to patrol the area, but the United States could not contribute. For the prisoners, Algeria wanted $60,000 (equivalent to millions in 2009 dollars), while America offered only $4,000. Jefferson said a million dollars would buy them off, but Congress would only appropriate $80,000. For eleven years, Americans who lived in Algeria lived as slaves to Algerian Moors. For a while, Portugal was patrolling the Straits of Gibraltar and preventing Barbary Pirates from entering the Atlantic. But they made a cash deal with the pirates, and they were again sailing into the Atlantic and engaging in piracy. By late 1793, a dozen American ships had been captured, goods stripped and everyone enslaved. Portugal had offered some armed patrols, but American merchants needed an armed American presence to sail near Europe. After some serious debate, the United States Navy was born in March 1794. Six frigates were authorized, and so began the construction of the United States, the Constellation, the Constitution and three other frigates.

In 1798, Napoleon's forces evicted the Knights of Malta from their island stronghold. As traditional enemies of the Barbary Corsairs, the policing power of the Knights was neutralized, after hundreds of years of mutual warfare.[25] The power of the Barbary Corsairs was unchecked.

19th century, United States-Barbary wars

One American slave reported that the Algerians had enslaved 130 American seamen in the Mediterranean and Atlantic from 1785 to 1793. Isolated cases of piracy occurred on the Rif coast of Morocco even at the beginning of the 20th century, but the pirate communities which could only live by plunder vanished with the French conquest of Algiers in 1830.[8]

This new military presence helped to stiffen American resolve to resist the continuation of tribute payments, leading to the two Barbary Wars along the North African coast: the First Barbary War from 1801 to 1805[26] and the Second Barbary War in 1815. It was not until 1815 that naval victories ended tribute payments by the U.S., although some European nations continued annual payments until the 1830s.

The United States Marine Corps actions in these wars led to the line "to the shores of Tripoli" in the opening of the Marine Hymn. Because of the hazards of boarding hostile ships, Marines' uniforms had a leather high collar to protect against cutlass slashes. This led to the nickname Leatherneck for U.S. Marines.[27]

After the general pacification of 1815, the European powers agreed upon the need to suppress the Barbary pirates. The sacking of Palma on the island of Sardinia by a Tunisian squadron, which carried off 158 inhabitants, roused widespread indignation. Other influences were at work to bring about their extinction. The United Kingdom had acquired Malta and the Ionian Islands and now had many Mediterranean subjects. It was also engaged in pressing the other European powers to join with it in the suppression of the slave trade which the Barbary states practiced on a large scale and at the expense of Europe. The suppression of the trade was one of the objects of the Congress of Vienna. The United Kingdom was called on to act for Europe, and in 1816 Lord Exmouth was sent to obtain treaties from Tunis and Algiers. His first visit produced diplomatic documents and promises and he sailed for England. While he was negotiating, a number of British subjects had been brutally treated at Bona, without his knowledge. The British government sent him back to secure reparation, and on August 17, in combination with a Dutch squadron under Admiral Van de Capellen, he administered a significant bombardment to Algiers. The lesson terrified the pirates both of that city and of Tunis into giving up over 3,000 prisoners and making fresh promises. Within a short time, however, Algiers renewed its piracies and slave-taking, though on a smaller scale, and the measures to be taken with the city's government were discussed at the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818. In 1824 another British fleet under Admiral Sir Harry Neal again bombarded Algiers. The city remained a haven for and source of pirates until its conquest by France in 1830.[8]

The thoroughness with which the French conquered and colonized Algeria put an effective end to piracy from the Barbary coast.

Barbary slaves

While Barbary corsairs naturally looted the cargo of ships they captured, their primary goal was to capture prisoners on land or at sea and turn them into slaves. Once captured, the slaves were often sold or put to work in various ways in North Africa.

It has been estimated that between 1530 and 1780 some one million, or one and a quarter million Europeans were captured and made slaves in North Africa, principally in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, with further captives in Istanbul and Sallee.[28]

The high point of slave trade was between 1605 and 1634, when there were 35,000 captive slaves at any given time in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. Furthermore, because of the high mortality rate in slaves, there was always a constant demand for more. The intelligent corsairs would raid ships or coastal areas and grab as many people as they possibly could. Then, they would come back a few days later and sell the villagers their own people back. If the families of the captives could not afford their family member back, merciless financiers would come and offer the families the extra cash they needed in exchange for their houses and land. If the families could not meet the deadline to get their family member back, it was of little concern to the corsairs, who knew they could sell the captives for a lot more money in the North African slave markets. However, they benefited from getting the family's ransom because it meant instant cash for them.

Being captured was just the first part of a slave's nightmare journey. Many slaves died on the ships during the long voyage back to North Africa due to disease or lack of food and water. For the "lucky" ones that did survive the journey, they were made a spectacle of as they walked through town on their way to the slave auction. The slaves would then have to stand from eight in the morning until two in the afternoon while buyers passed by and viewed them. Next came the auction, where the townspeople would bid on the slaves they wanted to purchase and once that was over, the governor of Algiers (the Dey) had the chance to purchase any slave he wanted for the price they were sold at the auction. During these auctions, the slaves would be forced to run and jump around to show their strength and stamina. After purchase, these slaves would either become slaves for ransom, or they would be put to work. There were a wide variety of jobs slaves had, from hard manual labor to doing housework (the job that almost all women slaves got). At night the slaves were put into prisons called 'bagnios' that were often hot and overcrowded. However, these bagnios began improving by the 1700s, and some bagnios had chapels, hospitals, shops, and bars run by slaves. Here, slaves were treated a little more fairly and were given the opportunity to run small businesses, and in some cases, make a small profit.[citation needed]

Galley slaves

Although the conditions in bagnios were harsh, they were nothing compared to what galley slaves had to go through. A galley is a ship that could be propelled solely by human power, and that is exactly what Barbary pirates had the slaves do. Barbary galleys were at sea for around eighty to a hundred days a year, so the slaves were not on them constantly, but when they were not rowing the galleys they were forced to do difficult manual labor on land. However, there were some exceptions; "galley slaves of the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul would be permanently confined to their galleys, and often served extremely long terms, averaging around nineteen years in the late seventeenth-century and early eighteenth-century periods. And these slaves simply rarely got off the galley but lived there for years."[29] During this time, rowers were shackled and chained where they sat, and were never allowed to leave. Sleeping (which was limited), eating, defecation and urination took place at the seat to which they were shackled. There was normally around five or six rowers on each oar, but this did not mean that any of the slaves could get away with any lack of effort. Overseers would walk back and forth and whip the slaves who were not rowing up to par.

Freedom for slaves

Barbary slaves could hope to be freed through payment of a ransom. Despite the efforts of middlemen and charities to raise money to provide ransoms, they were still very difficult to come by. Just as charity funding for slave ransoms increased, North African states kept increasing the amount of money that each slave was worth. However, lack of money was not the only problem standing between slaves and their freedom. Slaves would often need to notify their families that they were captive and inform them of the ransom price, and they would also need to pay the hefty mailing charge (which few slaves could afford) and wait several months for the mail to be delivered.

For the slaves and their families who were able to come up with the money, actually returning home was not guaranteed either. Redeemed slaves often went through a port to wait for the ransom to be finalized, and in some cases in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, slaves were kept at these ports as a quarantine due to fear of the plague.

Clearly, not many barbary slaves could depend on being rescued by ransoms, and instead had to look for the chance to escape. This was obviously easier said than done, since only a handful of slaves were actually able to escape. The most famous of runaway slaves was Thomas Pellow, who had the story of his journey published in 1740. After several failed attempts (which nearly resulted in his death), Pellow was finally able to escape to Gibraltar in July 1738.

Effects of barbary slavery on the world

Barbary piracy was not only an issue for the slaves, but for surrounding places as well. European maritime trade and commerce was greatly affected by barbary pirates and privateers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. After years of having ships raided, cargoes seized, and crews captured by the barbary corsairs, European states and eventually the U.S. took action. These countries "were forced to negotiate individual treaties with the sultan of Morocco and the governors (deys) of the Ottoman regencies of Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. The treaties consisted primarily of a yearly tribute to be paid to the North African rulers in exchange for safe passage of crews and goods."

Many[who?] have argued that barbary slavery between 1625-1640 was one of the reasons for the outbreak of civil war in England. King Charles I succeeded to the throne in 1625, and immediately faced tension with the English sailors, ship owners, and other coastal inhabitants. At this time, there were already hundreds of captives in the Barbary States. Merchants would not only lose their employees to the barbary corsairs, but also their vessels and goods. They were furious that King Charles I was not putting enough of the money that was earned from taxes and other forms of revenue toward security along the coastline. Furthermore, many of the captives were members of distraught families, who thought that anything that could be done to have their family members returned should be done. The King attempted to appease the masses and pay ransoms for the captives, but his efforts were thwarted by corruption in his government. King Charles I proposed having members of his government collect ransom money from townspeople, but often, the government official would claim to have freed many captives but instead keep the collected money to himself. By 1640, there were thousands of English captives in North Africa. As a result, King Charles I was very unpopular around the coast of England, and this helped lead[citation needed] to the Civil War in 1642.

But this was not the end of England's pirate issues. During the Napoleonic wars (1799–1815), the British relied on the Barbary States to supply its naval and commercial shipping with food and water so they chose to look the other way with regards to Barbary piracy and slavery. However, with the end of the Napoleonic wars, Britain decided it was time to take action and abolish slavery on the Barbary coastline. So in 1816, Great Britain commissioned Sir Edward Pellew to negotiate a treaty with the Barbary states.

Sir Edward was able to negotiate with many of the Barbary States such as Tunis and Tripoli, to whom he paid large tributes and was able to free over 1700 slaves. He was also able to convince these states to treat Christian captives as prisoners of war rather than slaves. Algiers however was less co-operative. While attempting to negotiate with the Algerian Dey, a misunderstanding resulted in the death of 200 Sardinian fishermen that were under British protection. After this, it was clear that war with Algiers was inevitable. On August 27, Sir Edward and his fleet attacked Algiers with full force, and after nine hours of fighting, 51,356 rounds shot, and 118 tons of powder spent, the Dey of Algiers was finally ready to negotiate. The Algiers casualties totalled around 7,000 men, while the British and Dutch losses were only about 900. The Dey agreed to all of Britain's demands, and a total of 1,211 slaves were released. Piracy declined substantially after the bombardment of Algiers but it was not until fourteen years later, in 1830, that the French annexed Algiers and piracy was ended forever in North Africa.

Famous pirates in Africa

The Barbarossa Brothers

Oruç Barbarossa

The most famous of the pirates in North Africa were the four Barbarossa brothers, who all became Barbary corsairs. However, only two of the Barbarossas became famous, Oruç and Hızır Hayreddin. Oruç, the oldest who gave the Barbarossas their name because of his red beard, captured the island of Djerba for the Ottoman Empire in 1502 or 1503. Often, Oruç would attack Spanish territories on the coast of North Africa, and during one failed attempt in 1512, Oruç lost his left arm to a cannon ball. The oldest Barbarossa would also go on a rampage through Algiers in 1516 and capture the town with the help of the Ottoman Empire. He executed the ruler of Algiers and everybody he suspected would oppose him, including local rulers. However, his ruthlessness and high taxes turned Algiers against him, and he was finally captured and killed by the Spanish in 1518 and put on display.

Hızır Hayreddin Barbarossa

However, Oruç was not the most famous pirate of the Barbarossas since he was more of a land-based criminal. His youngest brother Hızır (later named Hayreddin, pronounced Kheir ed-Din) was a more traditional pirate, and was actually a more capable pirate as he was a clever engineer and spoke at least six languages. But Hızır was obviously very fond of his eldest brother, and dyed his hair and beard with a reddish tint to honor Oruç. After capturing many crucial coastal areas, Hayreddinwas appointed admiral in chief of the Ottoman sultan's fleet. Under Hızır's command, the Ottoman empire was able to gain control and keep control of the eastern Mediterranean for over thirty years. Barbaros Hızır Hayreddin Pasha died in 1546 of either the plague or fever.

Captain Jack Ward

Another famous Barbary corsair was Captain Jack Ward - (also known as John Ward). He was once called, "beyond doubt the greatest scoundrel that ever sailed from England", by the English Ambassador to Venice. Ward was born in Faversham, England, but traveled to Plymouth when he got older in hopes to become a privateer for Queen Elizabeth during her war with Spain. Once the war was over, Ward, like many other ex-privateers, soon became bored with his life. He and some of his mates who were serving on board a naval vessel, decided to capture a ship and sail it to Tunis in North Africa. Here, Ward's ship was renamed Little John and he began his rather successful career as a pirate.

Ward captured many ships such as John Keyes' and the Fursman brothers' before he made his riches by capturing a 1500 ton Venetian vessel called Reneira a Soderina. He soon made it his primary boat and armed it with 60 cannons and 380 men. However, after an amazing voyage where he captured vessels whose combined value was around 400,000 crowns, Ward discovered an irreparable leak in the boat and he abandoned it along with most of his crew. Now an extremely wealthy man, Ward hoped to purchase a pardon and finally return home. But when his offer was denied, he stayed in Tunis and built himself a palace with his riches. Ward was the most notorious pirate in Tunis not only for his vast success as a pirate, but also for introducing the concept of using square-rigged and heavily armed ships (as opposed to galleys) to the North African area. This concept was a major reason for the Barbary's future dominance of the Mediterranean. Before dying of the plague in 1622, Jack Ward (like many other Christians who sailed North Africa) abandoned his religion and adopted the Muslim religion of the Ottoman Empire.

In fiction

Barbary Corsairs are protagonists in Le pantere di Algeri (the panthers of Algiers) by Emilio Salgari and appear in a number of other famous novels, including Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe, The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas, père, The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame The Sea Hawk and the Sword of Islam by Rafael Sabatini, The Algerine Captive by Royall Tyler, Master and Commander by Patrick O'Brian, the Baroque Cycle by Neal Stephenson, The Walking Drum by Louis Lamour, Doctor Doolittle by Hugh Lofting and Corsair by Clive Cussler. Miguel de Cervantes, the Spanish author, was captive for five years as a slave in the bagnio of Algiers, and reflected his experience in some of his books, including Don Quixote.

Barbary corsairs also feature in many pornographic novels, such as The Lustful Turk (1828), where the abduction of women into sexual slavery is an abiding interest.[30]

One of the stereotypical features of a pirate in popular culture, the eye patch, dates back to the Arab pirate Rahmah ibn Jabir al-Jalahimah, who wore it after losing an eye in battle in the 18th century.[31]

The Little Johnny England song "Lily of Barbary" tells the story of an English man who is enslaved by Barbary Corsairs and sold in Algiers, but is freed when his master dies. He then becomes a merchant and buys the freedom of another English slave girl.

See also

- Barbary Slave Trade

- Barbary treaties

- Ghazw Islamic raids

- History of Turkish navies

- Islam and slavery

- Knights Hospitaller Knights of Rhodes

- List of Ottoman sieges and landings

- Lundy - the largest island in the Bristol Channel, captured by Barbary pirates

- Ottoman–Habsburg wars

- Piyale Pasha a Croatian Ottoman admiral

- Romegas a member of the Knights of Saint John, one of the Order's greatest naval commanders

- Sack of Baltimore

- Spanish Empire

- Stephen Decatur

- USS Hornet (1805 sloop)

- Kemal Reis

- Seydi Ali Reis

- Salih Reis

- Kurtoğlu Muslihiddin Reis

- Kurtoğlu Hızır Reis

- Gedik Ahmed Pasha

- Uluç Ali Reis

- Murat Reis the Elder

- Chaka Bey

- Tybalt Rosembraise

Notes

- ^ A medieval term for the Maghreb after its Berber inhabitants.

- ^ a b "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast".

- ^ "Jefferson Versus the Muslim Pirates by Christopher Hitchens, City Journal Spring 2007".

- ^ Simon de Bruxelles (28 February 2007). "Pirates who got away with it by sailing closer to the wind". London: The Times. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ^ The Pirates of St. Tropez[dead link]

- ^ "Pirates: The Skull and Crossbones". Haifa Museum. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

- ^ Piracy on Crete, Creta News

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "The mysteries and majesties of the Aeolian Islands".

- ^ "Vieste".

- ^ "History of Menorca".

- ^ "When Europeans were slaves: Research suggests white slavery was much more common than previously believed".

- ^ "Watch-towers and fortified towns".

- ^ "The Order of Saint Stephen of Tuscany".

- ^ "Palazzo Pitti".

- ^ Rees Davies, British Slaves on the Barbary Coast, BBC, July 1, 2003

- ^ Mackie, Erin Skye, Welcome the Outlaw: Pirates, Maroons, and Caribbean Countercultures Cultural Critique - 59, Winter 2005, pp. 24-62

- ^ Alfred S. Bradford (2007), Flying the Black Flag, p. 132.

- ^ Ekin, Des (2006). The Stolen Village - Baltimore and the Barbary Pirates. OBrien. ISBN 9780862789558.

- ^ When Lord Exmouth sailed to coerce Algiers in 1816, he expressed doubts in a private letter whether the suppression of piracy would be acceptable to the trading community.

- ^ Roberts, Priscilla H. and Richard S. Roberts, Thomas Barclay (1728-1793): Consul in France, Diplomat in Barbary. Lehigh University Press, 2008. pp. 189-223.

- ^ Richard O'Brien-Thomas Jefferson, August 24, 1785, Boyd, Julian, et al. (eds), The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, v.8, p.440.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson and John Adams-John Jay, March 28, 1786, Boyd, Julian, et al. (eds), The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, v.9, p.358.

- ^ Oren, Michael B. (2005-11-03). "The Middle East and the Making of the United States, 1776 to 1815". Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- ^ http://www.knightshospitallers.org/history.htm

- ^ The Mariners' Museum : The Barbary Wars, 1801-1805[dead link]

- ^ Chenoweth, USMCR (Ret.), Col. H. Avery (2005). Semper fi: The Definitive Illustrated History of the U.S. Marines. New York: Main Street. ISBN 1-4027-3099-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ New book reopens old arguments about slave raids on Europe

- ^ Ekin, Des (2006). The Stolen Village - Baltimore and the Barbary Pirates. OBrien. p. 187. ISBN 9780862789558.

- ^ Steven Marcus (2008) The other Victorians: a study of sexuality and pornography in mid-nineteenth-Century England. Transaction Publishers, ISBN 1412808197, pp. 195–217

- ^ Charles Belgrave (1966), The Pirate Coast, p. 122, George Bell & Sons

References

- A History of Pirates by Angus Konstam

- Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. Thomas Dunne, 2003

- Forester, C. S. The Barbary Pirates. Random House, 1953

- Leiner, Frederick C. The End of Barbary Terror: America's 1815 War against the Pirates of North Africa. Oxford University Press, 2006

- Lambert, Frank. The Barbary Wars: American Independence in the Atlantic World. Hill & Wang, 2005

- To the Shores of Tripoli: The Birth of the U.S. Navy and Marines. -- Annapolis, MD : Naval Institute Press, c1991, 2001.

- World Navies

- Kristensen, Jens Riise. Barbary To and Fro Ørby publishing 2005. (www.oerby.dk)

- Clissold, Stephen. 1976. "CHRISTIAN RENEGADES AND BARBARY CORSAIRS." History Today 26, no. 8: 508-515. Historical Abstracts.

- Lloyd, Christopher. 1979. "Captain John Ward: Pirate." History Today 29, no. 11: 751. Religion and Philosophy Collection.

- Matar, Nabil. 2001. "THE BARBARY CORSAIRS, KING CHARLES I AND THE CIVIL WAR." Seventeenth Century 16, no. 2: 239-258. Historical Abstracts.

- Severn, Derek. "THE BOMBARDMENT OF ALGIERS, 1816." History Today 28, no. 1 (1978): 31-39. Historical Abstracts.

- Silverstein, Paul A. 2005. "THE NEW BARBARIANS: PIRACY AND TERRORISM ON THE NORTH AFRICAN FRONTIER." CR: The New Centennial Review 5, no. 1: 179-212. Historical Abstracts.

- Travers, Tim. Pirates: A History. Gloucestershire, Great Britain: Tempus Publishing, 2007.

Further reading

- London, Joshua E. Victory in Tripoli: How America's War with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005. ISBN 978-0471444152

- The Stolen Village Baltimore and the Barbary Pirates by Des Ekin ISBN 978-0862789558

- Knights Hospitaller of St. John - Order of St John of Jerusalem Malta

- Pirates of the Mediterranean

- Hitchens, Christopher (Spring 2007). "Jefferson Versus the Muslim Pirates". City Journal. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Lafi (Nora), Une ville du Maghreb entre ancien régime et réformes ottomanes. Genèse des institutions municipales à Tripoli de Barbarie (1795–1911), Paris: L'Harmattan, 2002, 305 pp.

- Skeletons on the Zahara: A True Story of Survival by Dean King, ISBN 0-31615935-2

- The Pirate Coast: by Richard Zacks Publisher: HYPERION ISBN 1-4013-0849-X

- CHRISTIAN SLAVES, MUSLIM MASTERS:White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500-1800 by Robert C. Davis.

- New book reopens old arguments about slave raids on Europe

- White Gold: The Extraordinary Story of Thomas Pellow and North Africa's One Million European Slaves by Giles Milton (Sceptre, 2005)

- Piracy, Slavery and Redemption: Barbary Captivity Narratives from Early Modern England by D. J. Vikus (Columbia University Press, 2001)

- Narrative of the Adventures and Sufferings of John R. Jewitt, only survivor of the crew of the ship Boston, during a captivity of nearly three years among the savages of Nootka Sound: with an account of the manners, mode of living, and religious opinions of the natives.

- To the Shores of Tripoli by A.B.C. Whipple (U.S. Naval Institute, 2001).

- The Barbary Pirates