Hepatitis A: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 387516830 by 41.184.22.203 (talk) |

|||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

Early symptoms of hepatitis A infection can be mistaken for [[influenza]], but some sufferers, especially children, exhibit no symptoms at all. Symptoms typically appear 2 to 6 weeks, (the [[incubation period]]), after the initial infection.<ref>{{cite web | title = Hepatitis A Symptoms | publisher = eMedicineHealth | url = http://www.emedicinehealth.com/hepatitis_a/page3_em.htm#Hepatitis%20A%20Symptoms | date = 2007-05-17 | accessdate = 2007-05-18}}</ref> |

Early symptoms of hepatitis A infection can be mistaken for [[influenza]], but some sufferers, especially children, exhibit no symptoms at all. Symptoms typically appear 2 to 6 weeks, (the [[incubation period]]), after the initial infection.<ref>{{cite web | title = Hepatitis A Symptoms | publisher = eMedicineHealth | url = http://www.emedicinehealth.com/hepatitis_a/page3_em.htm#Hepatitis%20A%20Symptoms | date = 2007-05-17 | accessdate = 2007-05-18}}</ref> |

||

Symptoms can return over the following |

Symptoms can return over the following 2-6 months and include:<ref>{{cite web | title = Hepatitis A : Fact Sheet | publisher = Center for Disease Control | url = http://www.cdc.gov/Ncidod/diseases/hepatitis/a/fact.htm | date = 2007-08-09 | accessdate = 2007-12-07}}</ref> |

||

* [[Fatigue (medical)|Fatigue]] |

* [[Fatigue (medical)|Fatigue]] |

||

Revision as of 19:36, 15 October 2010

| Hepatitis A | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

| Hepatitis A | |

|---|---|

| |

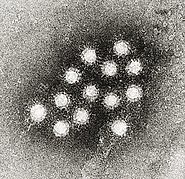

| Electron micrograph of hepatitis A virions. | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group IV ((+)ssRNA)

|

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | |

Hepatitis A (formerly known as infectious hepatitis) is an acute infectious disease of the liver caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV),[1] which is most commonly transmitted by the fecal-oral route via contaminated food or drinking water. Every year, approximately 10 million people worldwide are infected with the virus.[2] The time between infection and the appearance of the symptoms, (the incubation period), is between two and six weeks and the average incubation period is 28 days.[3]

In developing countries, and in regions with poor hygiene standards, the incidence of infection with this virus is high[4] and the illness is usually contracted in early childhood. HAV has also been found in samples taken to study ocean water quality.[5] Hepatitis A infection causes no clinical signs and symptoms in over 90% of infected children and since the infection confers lifelong immunity, the disease is of no special significance to the indigenous population. In Europe, the United States and other industrialized countries, on the other hand, the infection is contracted primarily by susceptible young adults, most of whom are infected with the virus during trips to countries with a high incidence of the disease.[3]

Hepatitis A does not have a chronic stage, is not progressive, and does not cause permanent liver damage. Following infection, the immune system makes antibodies against HAV that confer immunity against future infection. The disease can be prevented by vaccination, and hepatitis A vaccine has been proven effective in controlling outbreaks worldwide.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Early symptoms of hepatitis A infection can be mistaken for influenza, but some sufferers, especially children, exhibit no symptoms at all. Symptoms typically appear 2 to 6 weeks, (the incubation period), after the initial infection.[6]

Symptoms can return over the following 2-6 months and include:[7]

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea

- Diarrhea

- Appetite loss

- Depression

- Jaundice, a yellowing of the skin or whites of the eyes

- Sharp pains in the right-upper quadrant of the abdomen

- Weight loss

- Itching

- Bile is removed from blood stream and excreted in urine, giving it a dark amber colour

- Feces tend to be light in colour due to lack of bilirubin in bile

Pathogenesis

Following ingestion, HAV enters the bloodstream through the epithelium of the oropharynx or intestine.[8] The blood carries the virus to its target, the liver, where it multiplies within hepatocytes and Kupffer cells (liver macrophages). Virions are secreted into the bile and released in stool. HAV is excreted in large quantities approximately 11 days prior to appearance of symptoms or anti-HAV IgM antibodies in the blood. The incubation period is 15–50 days and mortality is less than 0.5%. Within the liver hepatocytes the RNA genome is released from the protein coat and is translated by the cell's own ribosomes. Unlike other members of the Picornaviruses this virus requires an intact eukaryote initiating factor 4G (eIF4G) for the initiation of translation.[9] The requirement for this factor results in an inability to shut down host protein synthesis unlike other picornaviruses. The virus must then inefficiently compete for the cellular translational machinery which may explain its poor growth in cell culture. Presumably for this reason the virus has strategically adopted a naturally highly deoptimized codon usage with respect to that of its cellular host. Precisely how this stategy works is not quite clear yet.

There is no apparent virus-mediated cytotoxicity presumably because of the virus' own requirement for an intact eIF4G and liver pathology is likely immune-mediated.

Diagnosis

Although HAV is excreted in the feces towards the end of the incubation period, specific diagnosis is made by the detection of HAV-specific IgM antibodies in the blood.[10] IgM antibody is only present in the blood following an acute hepatitis A infection. It is detectable from one to two weeks after the initial infection and persists for up to 14 weeks. The presence of IgG antibody in the blood means that the acute stage of the illness is past and the person is immune to further infection. IgG antibody to HAV is also found in the blood following vaccination and tests for immunity to the virus are based on the detection of this antibody.[10]

During the acute stage of the infection, the liver enzyme alanine transferase (ALT) is present in the blood at levels much higher than is normal. The enzyme comes from the liver cells that have been damaged by the virus.[11]

Hepatitis A virus is present in the blood, (viremia), and feces of infected people up to two weeks before clinical illness develops.[11]

Prevention

Hepatitis A can be prevented by vaccination, good hygiene and sanitation.[1][12] Hepatitis A is also one of the main reasons not to surf or go in the ocean after rains in coastal areas that are known to have bad runoff.[5]

The vaccine protects against HAV in more than 95% of cases for 10 years. It contains inactivated Hepatitis A virus providing active immunity against a future infection.[13][14] The vaccine was first phased in 1996 for children in high-risk areas, and in 1999 it was spread to areas with elevating levels of infection.[15]

The vaccine is given by injection into the muscle of the upper arm. An initial dose provides protection starting two to four weeks after vaccination; the second booster dose, given six to twelve months later, provides protection for up to twenty years.[13][15]

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for hepatitis A. Sufferers are advised to rest, avoid fatty foods and alcohol (these may be poorly tolerated for some additional months during the recovery phase and cause minor relapses), eat a well-balanced diet, and stay hydrated. Approximately 6–10% of people diagnosed with hepatitis A may experience one or more symptomatic relapse(s) for up to 40 weeks after contracting this disease.[16]

Prognosis

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1991 reported a low mortality rate for hepatitis A of 4 deaths per 1000 cases for the general population but a higher rate of 17.5 per 1000 in those aged 50 and over. Death usually occurs when the patient contracts Hepatitis A while already suffering from another form of Hepatitis, such as Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C.[17]

Young children who are infected with hepatitis A typically have a milder form of the disease, usually lasting from 1–3 weeks, whereas adults tend to experience a much more severe form of the disease.[18]

Epidemiology

Prevalence

HAV is found in the feces of infected persons and those who are at higher risk include travelers to developing countries where there is a higher incidence rate,[19] and those having sexual contact or drug use with infected persons.[20] There were 30,000 cases of Hepatitis A reported to the CDC in the U.S. in 1997. The agency estimates that there were as many as 270,000 cases each year from 1980 through 2000.[21]

Transmission

The virus spreads by the fecal-oral route and infections often occur in conditions of poor sanitation and overcrowding. Hepatitis A can be transmitted by the parenteral route but very rarely by blood and blood products. Food-borne outbreaks are not uncommon,[18] and ingestion of shellfish cultivated in polluted water is associated with a high risk of infection.[22] Approximately 40% of all acute viral hepatitis is caused by HAV.[8] Infected individuals are infectious prior to onset of symptoms, roughly 10 days following infection. The virus is resistant to detergent, acid (pH 1), solvents (e.g., ether, chloroform), drying, and temperatures up to 60oC. It can survive for months in fresh and salt water. Common-source (e.g., water, restaurant) outbreaks are typical. Infection is common in children in developing countries, reaching 100% incidence, but following infection there is life-long immunity. HAV can be inactivated by: chlorine treatment (drinking water), formalin (0.35%, 37oC, 72 hours), peracetic acid (2%, 4 hours), beta-propiolactone (0.25%, 1 hour), and UV radiation (2 μW/cm2/min).

Cases

The most widespread hepatitis A outbreak in the United States afflicted at least 640 people (killing four) in north-eastern Ohio and south-western Pennsylvania in late 2003. The outbreak was blamed on tainted green onions at a restaurant in Monaca, Pennsylvania.[23] In 1988, 300,000 people in Shanghai, China were infected with HAV after eating clams from a contaminated river.[8]

Virology

The Hepatitis virus (HAV) is a Picornavirus; it is non-enveloped and contains a single-stranded RNA packaged in a protein shell.[24] There is only one serotype of the virus, but multiple genotypes exist.[25] Codon use within the genome is biased and unusually distinct from its host. It also has a poor internal ribosome entry site[26] In the region that codes for the HAV capsid there are highly conserved clusters of rare codons that restrict antigenic variability.[27]

See also

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis B in China

- Hepatitis C

- Hepatitis D

- Hepatitis E

- Hepatitis F

- Hepatitis G

- Maurice Hilleman

References

- ^ a b Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 541–4. ISBN 0838585299.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Thiel TK (1998). "Hepatitis A vaccination". Am Fam Physician. 57 (7): 1500. PMID 9556642.

- ^ a b c Connor BA (2005). "Hepatitis A vaccine in the last-minute traveler". Am. J. Med. 118 Suppl 10A: 58S–62S. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.018. PMID 16271543.

- ^ Steffen R (2005). "Changing travel-related global epidemiology of hepatitis A". Am. J. Med. 118 Suppl 10A: 46S–49S. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.016. PMID 16271541. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Seven Surfing Sicknesses, .

- ^ "Hepatitis A Symptoms". eMedicineHealth. 2007-05-17. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- ^ "Hepatitis A : Fact Sheet". Center for Disease Control. 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- ^ a b c Murray, P. R., Rosenthal, K. S. & Pfaller, M. A. (2005) Medical Microbiology 5th ed., Elsevier Mosby.

- ^ Aragonès L, Guix S, Ribes E, Bosch A, Pintó RM (2010) Fine-tuning translation kinetics selection as the driving force of codon usage bias in the hepatitis a virus capsid. PLoS Pathog. 6(3):e1000797

- ^ a b Stapleton JT (1995). "Host immune response to hepatitis A virus". J. Infect. Dis. 171 Suppl 1: S9–14. PMID 7876654.

- ^ a b Musana KA, Yale SH, Abdulkarim AS (2004). "Tests of liver injury". Clin Med Res. 2 (2): 129–31. doi:10.3121/cmr.2.2.129. PMC 1069083. PMID 15931347.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "pmid15931347" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Hepatitis-A/Pages/Prevention.aspx?url=Pages/What-is-it.aspx

- ^ a b "Avaxim". NetDoctor.co.uk. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ Hammitt, LL; Bulkow, L; Hennessy, TW; Zanis, C; Snowball, M; Williams, JL; Bell, BP; Mcmahon, BJ (2008). "Persistence of antibody to Hepatitis A virus 10 years after vaccination among children and adults". J Infect Dis. 198 (12): 1776–1782. doi:10.1086/593335. PMID 18976095.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|author=and|last1=specified (help) - ^ a b "Hepatitis A Vaccine: What you need to know" (PDF). Vaccine Information Statement. CDC. 2006-03-21. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ Schiff ER (1992). "Atypical clinical manifestations of hepatitis A". Vaccine. 10 Suppl 1: S18–20. PMID 1475999.

- ^ Keeffe EB (2006). "Hepatitis A and B superimposed on chronic liver disease: vaccine-preventable diseases". Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 117: 227–37, discussion 237–8. PMC 1500906. PMID 18528476.

- ^ a b Brundage SC, Fitzpatrick AN (2006). "Hepatitis A". American Family Physician. 73 (12): 2162–8. PMID 16848078.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "pmid16848078" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Chapter 4 – Hepatitis, Viral, Type A – Yellow Book | CDC Travelers' Health

- ^ Hepatitis A: Fact Sheet | CDC Viral Hepatitis

- ^ Index | CDC Viral Hepatitis

- ^ Lees D (2000). "Viruses and bivalve shellfish". Int. J. Food Microbiol. 59 (1–2): 81–116. doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00248-8. PMID 10946842.

- ^ Hepatitis A Outbreak Associated with Green Onions at a Restaurant – Monaca, Pennsylvania, 2003

- ^ Cristina J, Costa-Mattioli M (2007). "Genetic variability and molecular evolution of hepatitis A virus". Virus Res. 127 (2): 151–7. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2007.01.005. PMID 17328982.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Costa-Mattioli M, Di Napoli A, Ferré V, Billaudel S, Perez-Bercoff R, Cristina J (2003). "Genetic variability of hepatitis A virus". J. Gen. Virol. 84 (Pt 12): 3191–201. doi:10.1099/vir.0.19532-0. PMID 14645901.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Whetter LE, Day SP, Elroystein O, Brown EA, Lemon SM (1994) Low efficiency of the 5' nontranslated region of hepatitis A virus RNA in directing cap-independent translation in permissive monkey kidney cells. J Virol 68: 5253–5263

- ^ Aragones L, Bosch A, Pinto RM (2008) Hepatitis A virus mutant spectra under the selective pressure of monoclonal antibodies: Codon usage constraints limit capsid variability. J Virol 82: 1688–1700

External links

- CDC's hepatitis A links

- CDC's hepatitis A Fact Sheet

- Hepatitis+A at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Hepatitis+A+virus at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Picornaviridae