Personifications of death: Difference between revisions

→In popular fiction: Added reference to Leiber's Death, and connected it to the Pratchett reference |

→In popular fiction: Added the citation for the Leiber material |

||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

During [[World War II]] imagery of Death was used in Allied animation films and posters for propaganda. |

During [[World War II]] imagery of Death was used in Allied animation films and posters for propaganda. |

||

One of the first appearances of a personification of Death in fantasy fiction is [[Fritz Leiber]]'s short story "The Sadness of the Executioner", which appears in the collection [[Swords and Ice Magic]]. The Death in question is described as "a relatively minor Death, only the Death of the World of Nehwon" (i.e. Leiber's fantasy world). This depiction of Death as a frustrated civil servant may have been influence on [[Terry Pratchett]], especially considering the opening story of [[The Colour of Magic]] is a tribute to Leiber's [[Lankhmar]]. |

One of the first appearances of a personification of Death in fantasy fiction is [[Fritz Leiber]]'s short story "The Sadness of the Executioner", which appears in the collection [[Swords and Ice Magic]]. The Death in question is described as "a relatively minor Death, only the Death of the World of Nehwon"<ref>Leiber, Fritz "The Sadness of the Executioner" in Swords and Ice Magic, Ace Books, 1977</ref>(i.e. Leiber's fantasy world). This depiction of Death as a frustrated civil servant may have been influence on [[Terry Pratchett]], especially considering the opening story of [[The Colour of Magic]] is a tribute to Leiber's [[Lankhmar]]. |

||

In [[Terry Pratchett]]'s [[Discworld]] series of novels, the character of [[Death (Discworld)|Death]] appears in almost every one of the series' 36 books. Donal Clarke of the [[The Irish Times|Irish Times]] called Death the most famous of Pratchett's characters and said that this version is "somewhat less fearsome than the version of the character in, say, Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal."<ref>{{cite news | last = Clarke | first = Donal| title = From fantasy to new reality| pages = 18| publisher = Irish Times| date = 2009-01-09| url = lexisnexis.com| accessdate = 2009-06-03 }}</ref> Terry Pratchett expands upon the idea that Death has, over time, taken on the traits of humanity, even to the point of having emotions and meddling in human (or human related) affairs. Terry Pratchett's Death tends to be philosophical and logical, and although he tries, Death often fails to understand humans. |

In [[Terry Pratchett]]'s [[Discworld]] series of novels, the character of [[Death (Discworld)|Death]] appears in almost every one of the series' 36 books. Donal Clarke of the [[The Irish Times|Irish Times]] called Death the most famous of Pratchett's characters and said that this version is "somewhat less fearsome than the version of the character in, say, Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal."<ref>{{cite news | last = Clarke | first = Donal| title = From fantasy to new reality| pages = 18| publisher = Irish Times| date = 2009-01-09| url = lexisnexis.com| accessdate = 2009-06-03 }}</ref> Terry Pratchett expands upon the idea that Death has, over time, taken on the traits of humanity, even to the point of having emotions and meddling in human (or human related) affairs. Terry Pratchett's Death tends to be philosophical and logical, and although he tries, Death often fails to understand humans. |

||

Revision as of 23:25, 26 March 2011

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

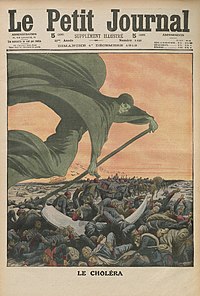

The concept of death as a sentient entity has existed in many societies since the beginning of history. In English, Death is often given the name Grim Reaper and, from the 15th century onwards, came to be shown as a skeletal figure carrying a large scythe and clothed in a black cloak with a hood. It is also given the name of the Angel of Death or Devil of Death or the angel of dark and light (Template:Lang-he-n Malach HaMavet) stemming from the Bible.

In some cases, the Grim Reaper is able to actually cause the victim's death,[1] leading to tales that he can be bribed, tricked, or outwitted in order to retain one's life, such as in the case of Sisyphus. Other beliefs hold that the Spectre of Death is only a psychopomp, serving to sever the last ties between the soul and the body and to guide the deceased to the next world without having any control over the fact of the victim's death.

In many languages (including English), Death is personified in male form, while in others, it is perceived as a female character (for instance, in Slavic languages).

Indo-European folklore / mythology

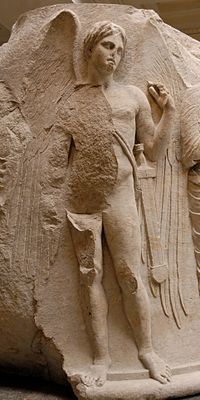

Hellenic

Ancient Greece found Death to be inevitable, and therefore, he is not represented as purely evil. He is often portrayed as a bearded and winged man, but has also been portrayed as a young boy. Death, or Thanatos, is the counterpart of life; death being represented as male, and life as female. He is the twin brother of Hypnos, the god of sleep. He is typically shown with his brother and is represented as being just and gentle. His job is to escort the deceased to the underworld, Hades. He then hands the dead over to Charon (who by some accounts looks like the modern Western interpretation of the Grim Reaper, having a skeletal body and black cloak), who mans the boat that carries them over the river Acheron, which separates the land of the living from the land of the dead. It was believed that if the ferryman did not receive some sort of payment, the soul would not be delivered to the underworld and would be left by the riverside for a hundred years. Thanatos' sisters, the Keres, were the spirits of violent death. They were associated with deaths from battle, disease, accident, and murder. They were portrayed as evil, often feeding on the blood of the body after the soul had been escorted to Hades. They had fangs, talons, and would be dressed in bloody garments.

Celtic

To the Welsh, he is Angeu and Ankou to Bretons.

Poland

In Poland, Death, or Śmierć, has an appearance similar to the traditional Grim Reaper, but instead of a black robe, Death has a white robe.

Baltic

Lithuanians named Death Giltinė, deriving from word gelti ("to sting"). Giltinė was viewed as an old, ugly woman with a long blue nose and a deadly poisonous tongue. The legend tells that Giltinė was young, pretty and communicative until she was trapped in a coffin for seven years. The goddess of death was a sister of the goddess of life and destiny, Laima, symbolizing the relationship between beginning and end.

Later, Lithuanians adopted the classic Grim Reaper with a scythe and black robe.

Hindu Scriptures

In Hindu scriptures, the lord of death is called Yama, or Yamaraj (literally "the lord of death"). Yamaraj rides a black buffalo and carries a rope lasso to carry the soul back to his abode, called "Yamalok"(the world of Yama - or the Underworld of the dead). There are many forms of reapers, although some say there is only one who disguises himself as a small child. His agents, the Yamaduts, carry souls back to Yamalok. There, all the accounts of a person's good and bad deeds are stored and maintained by Chitragupta. The balance of these deeds allows Yamaraj to decide where the soul has to reside in its next life, following the theory of reincarnation. Yama is also mentioned in the Mahabharata as a great philosopher and devotee of Supreme Brahman.

Yama is also known as Dharmaraj, or king of Dharma or justice. One interpertation is that justice is served equally to all whether they are alive or dead, based on their karma or fate. This is further strengthened by the idea that Yudhishtra, the eldest of the pandavas and considered as the personification of justice, was born due to Kunti's prayers to Yamaraj.

Buddhist scriptures also mention Yama or Yamaraj, much in the similar way.

Japanese mythology/folklore

In Kojiki, after giving birth to the fire god Hinokagutsuchi, the goddess Izanami dies from wounds from his fire and enters the perpetual night realm called Yomi-no-kuni (the underworld) that the gods retire to and to which Izanagi, her husband, traveled in a failed attempt to reclaim her. He discovers his wife as not-so beautiful anymore, and, following a brief argument afterwards, she promises him she will take a thousand lives every day, signifying her position as the goddess of death.

Another popular death personification is Enma (Yama), also known as 閻魔王 (Enma Ou) and 閻魔大王 (Enma Daiou) meaning "King Enma", or "Great King Enma" which are direct translations of Yama Rājā. He originated as Yama in Hinduism and later became Yanluo in China and Enma in Japan. Compare Chinese Buddhism. Enma rules the underworld, which makes him similar to Hades, and he decides whether someone dead goes to heaven or to hell. A saying parents[citation needed] use to scold children is that Enma will cut off their tongue in the afterlife if they lie.

There are also death gods called shinigami, which are closer to the Western tradition of the Grim Reaper. Shinigami (often plural) are common in modern Japanese arts and fiction and essentially absent from traditional mythology.

In Abrahamic religions

In the Bible, the fourth horseman of Book of Revelation is called Death and is pictured with Hades following him. The "Angel of the Lord" smites 185,000 men in the Assyrian camp (II Kings 19:35). When the Angel of Death passes through to smite the Egyptian first-born, God prevents "the destroyer" (shâchath) from entering houses with blood on the lintel and side posts (Exodus 12:23). The "destroying angel" (mal'ak ha-mashḥit) rages among the people in Jerusalem (II Sam. 24:16). In I Chronicles 21:15 the "angel of the Lord" is seen by King David standing "between the earth and the heaven, having a drawn sword in his hand stretched out over Jerusalem." The biblical Book of Job (33:22) uses the general term "destroyer" (memitim), which tradition has identified with "destroying angels" (mal'ake Khabbalah), and Prov. 16:14 uses the term the "angels of death" (mal'ake ha-mavet). Azra'il is sometimes referred as the Angel of Death as well.

Memitim

The memitim are a type of angel from biblical lore associated with the mediation over the lives of the dying. The name is derived from the Hebrew word mĕmītǐm and refers to angels that brought about the destruction of those whom the guardian angels no longer protected.[2] While there may be some debate among religious scholars regarding the exact nature of the memitim, it is generally accepted that, as described in the Book of Job 33:22, they are killers of some sort.[3]

In Judaism

Form and functions

According to the Midrash, the Angel of Death was created by God on the first day.[4] His dwelling is in heaven, whence he reaches earth in eight flights, whereas Pestilence reaches it in one.[5] He has twelve wings.[6] "Over all people have I surrendered thee the power," said God to the Angel of Death, "only not over this one which has received freedom from death through the Law."[7] It is said of the Angel of Death that he is full of eyes. In the hour of death, he stands at the head of the departing one with a drawn sword, to which clings a drop of gall. As soon as the dying man sees Death, he is seized with a convulsion and opens his mouth, whereupon Death throws the drop into it. This drop causes his death; he turns putrid, and his face becomes yellow.[8] The expression "to taste of death" originated in the idea that death was caused by a drop of gall.[9]

The soul escapes through the mouth, or, as is stated in another place, through the throat; therefore, the Angel of Death stands at the head of the patient (Adolf Jellinek, l.c. ii. 94, Midr. Teh. to Ps. xi.). When the soul forsakes the body, its voice goes from one end of the world to the other, but is not heard (Gen. R. vi. 7; Ex. R. v. 9; Pirḳe R. El. xxxiv.). The drawn sword of the Angel of Death, mentioned by the Chronicler (I. Chron. 21:15; comp. Job 15:22; Enoch 62:11), indicates that the Angel of Death was figured as a warrior who kills off the children of men. "Man, on the day of his death, falls down before the Angel of Death like a beast before the slaughterer" (Grünhut, "Liḳḳuṭim", v. 102a). R. Samuel's father (c. 200) said: "The Angel of Death said to me, 'Only for the sake of the honor of mankind do I not tear off their necks as is done to slaughtered beasts'" ('Ab. Zarah 20b). In later representations, the knife sometimes replaces the sword, and reference is also made to the cord of the Angel of Death, which indicates death by throttling. Moses says to God: "I fear the cord of the Angel of Death" (Grünhut, l.c. v. 103a et seq.). Of the four Jewish methods of execution, three are named in connection with the Angel of Death: Burning (by pouring hot lead down the victim's throat), slaughtering (by beheading), and throttling. The Angel of Death administers the particular punishment that God has ordained for the commission of sin.

A peculiar mantle ("idra"-according to Levy, "Neuhebr. Wörterb." i. 32, a sword) belongs to the equipment of the Angel of Death (Eccl. R. iv. 7). The Angel of Death takes on the particular form which will best serve his purpose; e.g., he appears to a scholar in the form of a beggar imploring pity (The beggar should receive Tzedakah.)(M. Ḳ. 28a). "When pestilence rages in the town, walk not in the middle of the street, because the Angel of Death [i.e., pestilence] strides there; if peace reigns in the town, walk not on the edges of the road. When pestilence rages in the town, go not alone to the synagogue, because there the Angel of Death stores his tools. If the dogs howl, the Angel of Death has entered the city; if they make sport, the prophet Elijah has come" (B. Ḳ. 60b). The "destroyer" (saṭan ha-mashḥit) in the daily prayer is the Angel of Death (Ber. 16b). Midr. Ma'ase Torah (compare Jellinek, "B. H." ii. 98) says: "There are six Angels of Death: Gabriel over kings; Ḳapẓiel over youths; Mashbir over animals; Mashḥit over children; Af and Ḥemah over man and beast."

Death and Satan

The Angel of Death, who is identified by some with Satan, immediately after his creation had a dispute with God as to the light of the Messiah (Pesiḳ. R. 161b). When Eve touched the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, she perceived the Angel of Death, and thought, "Now I shall die, and God will create another wife for Adam."[10] Adam also had a conversation with the Angel of Death (Böklen, "Die Verwandtschaft der Jüdisch-Christlichen mit der Parsischen Eschatologie", p. 12). The Angel of Death sits before the face of the dead (Jellinek, l.c. ii. 94). While Abraham was mourning, for Sarah the angel appeared to him, which explains why "Abraham stood up from before his death".[11] Samael told Sarah that Abraham had sacrificed Isaac in spite of his wailing, and Sarah died of horror and grief.[12] It was Moses who most often had dealings with the angel. At the rebellion of Korah, Moses saw him (Num. R. v. 7; Bacher, l.c. iii. 333; compare Sanh. 82a). It was the Angel of Death in the form of Pestilence who snatched away 15,000 every year during the wandering in the wilderness (ib. 70). When Moses reached heaven, the angel told him something (Jellinek, l.c. i. 61).

When the Angel of Death came to Moses and said, "Give me thy soul," Moses called to him: "Where I sit thou hast no right to stand." The Angel retired ashamed and reported the occurrence to God. Again, God commanded him to bring the soul of Moses. The Angel went and, not finding him, inquired of the sea, of the mountains, and of the valleys; but they knew nothing of him.[13] Really, Moses did not die through the Angel of Death, but through God's kiss (bi-neshiḳah); i.e., God drew his soul out of his body (B. B. 17a; compare Abraham in Apocryphal and Rabbinical Literature, and parallel references in Böklen, l.c. p. 11). Legend seizes upon the story of Moses' struggle with the Angel of Death and expands it at length (Tan., ed. Stettin, pp. 624 et seq.; Deut. R. ix., xi.; Grünhut, l.c. v. 102b, 169a). As Benaiah bound Ashmedai (Jew. Encyc. ii. 218a), so Moses binds the Angel of Death that he may bless Israel.[14]

Solomon once noticed that the Angel of Death was grieved. When questioned as to the cause of his sorrow, he answered: "I am requested to take your two beautiful scribes." Solomon at once charged the demons to convey his scribes to Luz, where the Angel of Death could not enter. When they were near the city, however, they both died. The Angel laughed on the next day, whereupon Solomon asked the cause of his mirth. "Because," answered the Angel, "thou didst send the youths thither, whence I was ordered to fetch them" (Suk. 53a). In the next world, God will let the Angel of Death fight against Pharaoh, Sisera, and Sennacherib.[15]

Scholars and the Angel of Death

Talmud teachers of the fourth century associate quite familiarly with him. When he appeared to one on the street, the teacher reproached him with rushing upon him as upon a beast, whereupon the angel called upon him at his house. To another, he granted a respite of thirty days, that he might put his knowledge in order before entering the next world. To a third, he had no access, because he could not interrupt the study of the Talmud. To a fourth, he showed a rod of fire, whereby he is recognized as the Angel of Death (M. K. 28a). He often entered the house of Bibi and conversed with him (Ḥag. 4b). Often, he resorts to strategy in order to interrupt and seize his victim (B. M. 86a; Mak. 10a).

The death of Joshua ben Levi in particular is surrounded with a web of fable. When the time came for him to die and the Angel of Death appeared to him, he demanded to be shown his place in paradise. When the angel had consented to this, he demanded the angel's knife, that the angel might not frighten him by the way. This request also was granted him, and Joshua sprang with the knife over the wall of paradise; the angel, who is not allowed to enter paradise, caught hold of the end of his garment. Joshua swore that he would not come out, and God declared that he should not leave paradise unless he was absolved from his oath; if not absolved, he was to remain. The Angel of Death then demanded back his knife, but Joshua refused. At this point, a heavenly voice (bat ḳol) rang out: "Give him back the knife, because the children of men have need of it" (Ket. 77b; Jellinek, l.c. ii. 48-51; Bacher, l.c. i. 192 et seq.).

Rabbinic views

The Rabbis found the Angel of Death mentioned in Psalm 134:45 (A. V. 48), where the Targum translates: "There is no man who lives and, seeing the Angel of Death, can deliver his soul from his hand." Eccl. 8:4 is thus explained in Midrash Rabbah to the passage: "One may not escape the Angel of Death, nor say to him, 'Wait until I put my affairs in order,' or 'There is my son, my slave: take him in my stead.'" Where the Angel of Death appears, there is no remedy (Talmud, Ned. 49a; Hul. 7b). If one who has sinned has confessed his fault, the Angel of Death may not touch him (Midrash Tanhuma, ed. Buber, 139). God protects from the Angel of Death (Midrash Genesis Rabbah lxviii.).

By acts of benevolence, the anger of the Angel of Death is overcome; when one fails to perform such acts the Angel of Death will make his appearance (Derek Ereẓ Zuṭa, viii.). The Angel of Death receives his order from God (Ber. 62b). As soon as he has received permission to destroy, however, he makes no distinction between good and bad (B. Ḳ. 60a). In the city of Luz. the Angel of Death has no power, and, when the aged inhabitants are ready to die, they go outside the city (Soṭah 46b; compare Sanh. 97a). A legend to the same effect existed in Ireland in the Middle Ages (Jew. Quart. Rev. vi. 336).

In Christianity

Death is, either as a metaphor, a personification or an actual being, referenced occasionally in the New Testament. One such personification is found in Acts 2:24 – "But God raised Him [Jesus] from the dead, freeing Him from the agony of death, because it was impossible for Death to keep its hold on Him." Later passages, however, are much more explicit. Romans 5 speaks of Death as having "reigned from the time of Adam to the time of Moses," and various passages in the Epistles speak of Christ's work on the cross and His resurrection as a confrontation with Death. Such verses include Rom. 6:9 and 2 Tim. 1:10. Death is still viewed as enduring in Scripture. 1 Cor. 15:26 asserts, "The last enemy to be destroyed is Death," which implies that Death has not been destroyed once and for all. This assertion later proves true in the Book of Revelation.

The author of the Epistle to the Hebrews declares that Satan "holds the power of Death" (Heb. 2:14). It is written that Son became human that by his death he might destroy the devil; this is the head of the Beast referred to as, "One of the heads of the beast seemed to have had a fatal wound, but the fatal wound had been healed" (Rev. 13:3) as well as the head of the serpent as preemptively referred to in Genesis 3:15 - "And I will put enmity Between you and the woman, And between your seed and her seed; He shall bruise you on the head, And you shall bruise Him on the heel". If the head that was fatally wounded but healed refers to Death, this accords with 2 Tim. 1:10, which states that Jesus "has destroyed Death", and the implication that Death was yet to be destroyed in 1 Cor. 15:26. The victory over Death is also referred to as "Eternal Life"

The final destruction of Death is referenced by Paul in the fifteenth chapter of 1 Corinthians; he says that after the general resurrection, the prophecies of Isaiah 25:8 and Hosea 13:14 – "He will swallow up Death forever", and "Where, O Death, is your sting?" (Septuagint), will be fulfilled. According to Paul, the power of Death lies in sin, which is made possible by the Law, but God "gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ." That victory over Death is also discussed in the Revelation of John.

In the visions of John, Death is used as one of the metaphorical Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Rev. 6:8 reads, "I looked, and there before me was a pale horse! Its rider was named Death, and Hades was following close behind him. They were given power over a fourth of the earth to kill by sword, famine and plague, and by the wild beasts of the earth". In Rev. 20:13-14, in the vision of judgment of the dead, it is written, "The sea gave up the dead that were in it, and Death and Hades gave up the dead that were in them, and each person was judged according to what he had done. Then Death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. The lake of fire is the second death." This describes the destruction of the last enemy. After this, "He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away" (Rev. 21:4).

In Roman Catholicism, the archangel Michael is viewed as the good Angel of Death (as opposed to Samael, the controversial Angel of Death), carrying the souls of the deceased to Heaven. There, he balances them in his scales (one of his symbols). He is said to give the dying souls the chance to redeem themselves before passing as well. In Mexico, a popular folk-Catholic belief regards the Angel of Death as a saint, known as Santa Muerte, but this local cultus is not acknowledged by the Church.

In Islam

In Islam, the concept of death is viewed as a celebratory event as opposed to one to be dreaded. It is the passage of the everlasting soul into a closer dimension to its creator that is seen as a point of joy, rather than misery, obvious mortal grief and sadness not withstanding. Indeed, the Islamic prophet Muhammad demonstrated that grief was an acceptable form of what makes us human, however prolonged mourning at the expense of the living is inappropriate, especially in the light of the transition from one world to the next.

Death is represented by Azra'il [Citation needed], one of Allah's archangels in the Quran:

6:93: "If thou couldst see, when the wrong-doers reach the pangs of death and the angels stretch their hands out, saying: Deliver up your souls."

32:11: "Say: The Angel of Death, who hath charge concerning you, will gather you and afterward unto your Lord ye will be returned."

The irony of the Angel of Death refers to his involvement in the creation of life. In these verses the Angel of Death and his assistants are sent to take the soul of those destined to die. Who is the Angel of Death? When God wanted to create Adam, he sent one of the Angels of the Throne to bring some of the Earth's clay to fashion Adam from it. When the angel came to earth to take the clay, the earth told him: "I beseech you by the One Who sent you not to take anything from me to make someone who will be punished one day." [Citation needed] When the angel returned empty-handed, God asked him why he did not bring back any clay. The angel said: "The earth besought me by Your greatness not to take anything from it." [Citation needed] Then God sent another angel, but the same thing happened, and then another, until God decided to send Azra'il, the Angel of Death. The earth spoke to him as it had spoken to the others, but Azra'il said: "Obedience to God is better than obedience to you, even if you beseech me by His greatness." [Citation needed] And Azra'il took clay from the Earth's east and its west, its north and its south, and brought it back to God. God poured some water of paradise on this clay and it became soft, and from it He created Adam. [Citation needed]

He is mistakenly known by the name of "Izrail" (not to be confused with Israel, which is a name in Islam solely for Prophet Ya'qoob/Jacob), since the name Izrael is not mentioned in the Quran nor Hadith, the English form of which is Azra'il. He is charged with the task of separating and returning from the bodies the souls of people who are to be recalled permanently from the physical world back to the primordial spiritual world. This is a process whose aspect varies depending on the nature and past deeds of the individual in question, and it is known that the Angel of Death is also accompanied by helpers or associates.

Apart from the characteristics and responsibilities he has in common with other angels in Islam, little else concerning the Angel of Death can be derived from fundamental Muslim texts. Many references are made in various Muslim legends, however, some of which are included in books authored by Muslim poets and mystics (Sufis who do not have citations from Quran nor Sunnah). For instance, it is said that when someone's time has come, the angel of death appears only to him and to no one else even if he is in a room full of people. If this person has more sins than good deeds the angel would appear to him in a vile and ugly form. The angel would rip his soul from him in an agonizing way. If the person has more good deeds than sins the angel would take his soul from him as gently as a mother rocking her baby.

The following tale is related in the Naqshbandi order of Sufism on the practicalities of sweeping up human souls from the expanse of the earth:

The Prophet Abraham once asked Azra'il who has two eyes in the front of his head and two eyes in the back: "O Angel of Death! What do you do if one man dies in the east and another in the west, or if a land is stricken by the plague, or if two armies meet in the field?" The angel said: "O Messenger of God! the names of these people are inscribed on the lawh al-mahfuz: It is the 'Preserved Tablet' on which all human destinies are engraved. I gaze at it incessantly. It informs me of the moment when the lifetime of any living being on earth has come to an end, be it one of mankind or one of the beasts. There is also a tree next to me, called the Tree of Life. It is covered with myriads of tiny leaves, smaller than the leaves of the olive-tree and much more numerous. Whenever a person is born on earth, the tree sprouts a new leaf, and on this leaf is written the name of that person. It is by means of this tree that I know who is born and who is to die. When a person is going to die, his leaf begins to wilt and dry, and it falls from the tree onto the tablet. Then this person's name is erased from the Preserved Tablet. This event happens forty days before the actual death of that person. We are informed forty days in advance of his impending death. That person himself may not know it and may continue his life on earth full of hope and plans. However, we here in the heavens know and have that information. That is why God has said: 'Your sustenance has been written in the heavens and decreed for you,' and it includes the life-span. The moment we see in heaven that leaf wilting and dying we mix it into that person's provision, and from the fortieth day before his death he begins to consume his leaf from the Tree of Life without knowing it. Only forty days then remain of his life in this world, and after that there is no provision for him in it. Then I summon the spirits by God's leave, until they are present right before me, and the earth is flattened out and left like a dish before me, from which I partake as I wish, by God's order." [Citation needed from QURAN AND SUNNAH not a Suffi order!]

— , Naqshbandi.net)

In popular fiction

A personified character of Death has recurred many times in popular fiction. The character can be found in early pieces, such as the fifteenth century morality play Everyman.

In the present day, death is portrayed in many mediums of popular fiction. One of the most iconic portrayals is that of the 1957 film The Seventh Seal, by Swedish director Ingmar Bergman. In it is one of the most influential (and heavily symbolic) movie depictions of Death in the modern use of sound cinema history. In the collective scene, a medieval knight (Max Von Sydow) returning from a crusade plays a game of chess with Death, with the knight's life depending upon the outcome of the game. American film critic Roger Ebert remarked that this image "[is] so perfect it has survived countless parodies."[16]

During World War II imagery of Death was used in Allied animation films and posters for propaganda.

One of the first appearances of a personification of Death in fantasy fiction is Fritz Leiber's short story "The Sadness of the Executioner", which appears in the collection Swords and Ice Magic. The Death in question is described as "a relatively minor Death, only the Death of the World of Nehwon"[17](i.e. Leiber's fantasy world). This depiction of Death as a frustrated civil servant may have been influence on Terry Pratchett, especially considering the opening story of The Colour of Magic is a tribute to Leiber's Lankhmar.

In Terry Pratchett's Discworld series of novels, the character of Death appears in almost every one of the series' 36 books. Donal Clarke of the Irish Times called Death the most famous of Pratchett's characters and said that this version is "somewhat less fearsome than the version of the character in, say, Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal."[18] Terry Pratchett expands upon the idea that Death has, over time, taken on the traits of humanity, even to the point of having emotions and meddling in human (or human related) affairs. Terry Pratchett's Death tends to be philosophical and logical, and although he tries, Death often fails to understand humans.

An atypical personification of Death appears in The Sandman, a series of comic books written by Neil Gaiman, in which Death, one of the Endless, is depicted as a woman whose image and attire change to match with the human styles of the times.[19][20]

In Markus Zusak's The Book Thief, Death is personified as a gentle, cynical observer of the Holocaust, and narrates the story of one girl's life.

The personification of death was also a main character in the children's cartoon "The Grim Adventures of Billy and Mandy" under the name Grim. He is portrayed as a living skeleton dressed in a long black, hooded cloak, and carrying a scythe which holds most of his powers. After losing a bet with the two children, Billy and Mandy, he is forced to become their best friend forever. His role, and the show overall, is purely comical, while poking fun at various myths and legends, as well as modern day current events.

The Grim Reaper was known as, The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come in the Charles Dickens novel book, entitled A Christmas Carol.

An angel of death named Andrew appeared on the long-running drama series Touched by an Angel.

Death often appears on the science-fiction series Supernatural, personified as on aged man with a taste for fast food.

In Dead Like Me, the Grim Reaper is actually many "Grim Reapers". And "a Reaper's job is to remove the souls of people, preferably just before they die, and escort them until they move on into their afterlife."

In the Marvel Universe of superhero comics, Death is an abstract entity that along with Eternity plays a vital role in the metaphysical structure of the cosmos. As an abstract being, Death has no true physical form or gender but typically manifests as female, most often as a female skeleton in hooded robe though she once famously appeared to Thanos of Titan in a form so beautiful that he fell in love with her and since devoted his existence to her service.

See also

- Banshee

- Danse Macabre

- Death deity

- Dracula

- Personification

- Prehistoric religion

- Psychopomp

- Santa Muerte

- Satan

- Shinigami

- The Wraith: Shangri-La

Notes

- ^ Hallucinations of the Grim Reaper may cause death especially in a person who is very sick and close to dying by destroying that person's confidence that he/she can survive, see Nocebo effect.

- ^ Olyan, S.M., A Thousiand Thousands Served Him: Exegesis likes it hard in it and the Naming of Angels in Ancient Judaism, page 21.

- ^ Gordon, M.B., Medicine among the Ancient Hebrews, page 472.

- ^ Midrash Tanhuma on Genesis 39:1

- ^ Talmud Berakhot 4b

- ^ Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer 13

- ^ Midrash Tanhuma on Exodus 31:18

- ^ Talmud Avodah Zarah 20b; on putrefaction see also Pesikta de-Rav Kahana 54b; for the eyes compare Ezekiel 1:18 and Revelation 4:6

- ^ Jewish Quarterly Review vi. 327

- ^ Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer 13, end; compare Targum Jonathan to Genesis 3:6, and Yalkut Shimoni 25)

- ^ Genesis 23:3; Genesis Rabba 63:5, misunderstood by the commentators

- ^ Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer 32

- ^ Sifre Deuteronomy 305

- ^ Pesikta de-Rav Kahana 199, where lifne moto(Deuteronomy 33:1) is explained as meaning "before the Angel of Death")

- ^ Yalkut Shimoni 428

- ^ Ebert, Roger (2000-04-16). ":: rogerebert.com :: Great Movies :: The Seventh Seal". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2007-07-28.

- ^ Leiber, Fritz "The Sadness of the Executioner" in Swords and Ice Magic, Ace Books, 1977

- ^ Clarke, Donal (2009-01-09). [lexisnexis.com "From fantasy to new reality"]. Irish Times. p. 18. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Tuscaloosanews.com

- ^ Wired.com

Bibliography

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kaufmann Kohler and Ludwig Blau (1901–1906). "Angel of Death". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kaufmann Kohler and Ludwig Blau (1901–1906). "Angel of Death". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- Bender, A. P. (1894). "Beliefs, Rites, and Customs of the Jews, Connected with Death, Burial, and Mourning". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 6 (2): 317–347. doi:10.2307/1450143.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Bender, A. P. (1894). "Beliefs, Rites, and Customs of the Jews, Connected with Death, Burial, and Mourning". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 6 (4): 664–671. doi:10.2307/1450184.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Böklen, Ernst (1902). Die Verwandtschaft der Jüdisch-Christlichen mit der Parsischen Eschatologie. Göttingen: Vendenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Dillmann, August (1895). Handbuch der alttestamentlichen Theologie. Leipzig: S. Hirzel.

- Gordon, M.B., Medicine among the Ancient Hebrews. Isis, Vol. 33, No. 4 (Dec., 1941), pp. 454–485.

- Hamburger, R. B. T. i. 990-992:

- Joël, David (1881). Der Aberglaube und die Stellung des Judenthums zu Demselben. Breslau: F.W. Jungfer's Buch.

- Kohut, Alexander (1866). Ueber die Jüdische Angelologie und Dämonologie in Ihrer Abhängigkeit vom Parsismus. Leipzig: Brockhaus.

- Milton, John. Paradise Lost.

- Olyan, S.M., A Thousand Thousands Served Him: Exegesis and the Naming of Angels in Ancient Judaism. 150 pp. J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), Tübingen, 1993.

- Schwab, Moïse (1897). Vocabulaire de l'Angélologie d'Après les Manuscrits Hebreux de la Bibliothèque Nationale. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stave, Erik (1898). Ueber den Einfluss des Parsismus auf das Judenthum. Haarlem: E. F. Bohn.

- Weber, F. W. (1897). Jüdische Theologie auf Grund des Talmud und verwandter Schriften, gemeinfasslich dargestellt. Leipzig: Dörffling & Franke.

- Winer, B. R. ii. 383-386;