Charleston, South Carolina: Difference between revisions

Reverted to revision 519807813 by Ptbotgourou: Reverting nonsense edit. (TW) |

|||

| Line 346: | Line 346: | ||

==== Police department ==== |

==== Police department ==== |

||

The [[City of Charleston Police Department]], with a total of |

The [[City of Charleston Police Department]], with a total of 412 sworn officers, 137 civilians and 27 reserve police officers, is South Carolina's largest police department.[http://www.charlestoncity.info/dept/content.aspx?nid=237&cid=1109] Their procedures on cracking down on drug use and gang violence in the city are used as models to other cities to do the same.{{Citation needed|date=October 2010}} According to the final 2005 FBI Crime Reports, Charleston crime level is worse than the national average in almost every major category.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://charlestonsc.areaconnect.com/crime1.htm |title=2005 FBI Crime Reports |publisher=Charlestonsc.areaconnect.com |date= |accessdate=2009-02-25}}</ref> Greg Mullen, the former Deputy Chief of Police in the City of [[Virginia Beach, Virginia]], serves as the current police chief. The former Charleston police chief was Reuben Greenberg who resigned August 12, 2005. Greenberg was credited with creating a polite police force that kept [[police brutality]] well in check, even as it developed a visible presence in community policing and a significant reduction in crime rates.<ref>[[Michael Ledeen]], [http://www.nationalreview.com/ledeen/ledeen200508180822.asp "Hail to the Chief,"] ''[[National Review Online]]'', August 18, 2005. Retrieved June 18, 2007.</ref> |

||

==== EMS and medical centers ==== |

==== EMS and medical centers ==== |

||

Revision as of 01:23, 3 November 2012

Charleston | |

|---|---|

| City of Charleston | |

Broad Street, showing St. Michael's Church on Meeting Street | |

|

| |

| Nickname(s): "The Holy City", "Chucktown" | |

| Motto(s): Aedes mores juraque curat (Latin = She guards her buildings, customs, and laws) | |

| Country | United States |

| Historic Countries | Confederate States, England |

| State | South Carolina |

| Historic Colony | Colony of South Carolina |

| Counties | Charleston, Berkeley |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Joseph P. Riley, Jr. (D) |

| Area | |

| • City | 164.1 sq mi (405.5 km2) |

| • Land | 147.0 sq mi (361.2 km2) |

| • Water | 17.1 sq mi (44.3 km2) |

| Elevation | 20 ft (4 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 122,689 (US: 210th) |

| • Metro | 664,607 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Area code | 843 |

| FIPS code | 45-13330Template:GR |

| GNIS feature ID | 1221516 |

| Website | www.charleston-sc.gov |

Charleston is the second largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, surpassed only by the state capital of Columbia. Charleston is the county seat of the modern Charleston County.Template:GR

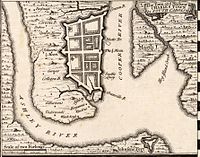

In 1670, Charleston was originally named Charles Towne. It moved to its present location on Oyster Point in 1680 from a location on the west bank of the Ashley River known as Albemarle Point. Charleston adopted its present name in 1783. In 1690, Charleston was the fifth largest city in North America,[2] and remained among the ten largest cities in the United States through the 1840 census.[3] As defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, and used by the U.S. Census Bureau for statistical purposes only, Charleston is a principal city for the Charleston–North Charleston–Summerville Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Charleston-North Charleston urban area.

Charleston is known as The Holy City perhaps by virtue of the prominence of churches on the low-rise cityscape, perhaps because, like Mecca, its devotees hold it so dear [4], and perhaps for the fact that Carolina was among the few original thirteen colonies to provide toleration for all Protestant religions, though it was not open to Roman Catholics.[5] Many Huguenots found their way to Charleston.[6] Carolina also allowed Jews to practice their faith without restriction. Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, founded in 1749, is the fourth oldest Jewish congregation in the continental United States.[7] Brith Sholom Beth Israel is the oldest Orthodox synagogue in the South, founded by Ashkenazi (German and Central European Jews) Jews in the mid-19th century.[8]

The population was counted by the 2010 census at 120,083, making it the second most populous city in South Carolina, closely behind the state capital Columbia. The 2011 estimates places Charleston with a population of 122,689. Current trends put Charleston as the fastest-growing municipality in South Carolina. The city's metropolitan area population was counted by the 2010 census at 664,607 – the second largest in the state – and the 75th-largest metropolitan statistical area in the United States.

The city of Charleston is located just south of the midpoint of South Carolina's coastline, at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper rivers, which flow together into the Atlantic Ocean. Charleston Harbor lies between downtown Charleston and the Atlantic Ocean. Charleston's name is derived from Charles Towne, named after King Charles II of England.

In 2011, Charleston was named #1 U.S. City by Conde Nast Traveler's Readers' Choice Awards and #2 Best City in the U.S. and Canada by Travel + Leisure's World's Best Awards. Also in 2011, Bon Appetit magazine named Husk, located on Queen Street in Charleston, the Best New Restaurant in America. America's most-published etiquette expert, Marjabelle Young Stewart, recognized Charleston 1995 as the "best-mannered" city in the U.S,[9] a claim lent credibility by the fact that it has the first established Livability Court in the country. In 2011, Travel and Leisure Magazine named Charleston "America's Sexiest City", as well as "America's Most Friendly." Subsequently, Southern Living Magazine named Charleston "the most polite and hospitable city in America." In 2012, Travel and Leisure voted Charleston as the second best-dressed city in America, only behind New York City.[10]

South Carolina's Lowcountry holds a major place of importance in African-American history for many reasons, but perhaps most importantly as a port of entry for people of African descent. According to several historians, anywhere from 40 to 60 percent of the Africans who were brought to America during the slave trade entered through ports in the Lowcountry.

This has given the Lowcountry the designation among some as the "Ellis Island for African Americans," although some dispute this term, as the Ellis Island immigrants arrived voluntarily as opposed to the Africans who were captured in the Atlantic slave trade.

According to Peter Wood in his book "Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 to the Stono Rebellion," the successful cultivation of rice in the Lowcountry in the 1600s was a major factor in the importation of African labor. Sir Jonathan Atkins was quoted in 1680 as saying, "Since people have found out the convenience and cheapness of slave labor they no longer keep white men, who formerly did the work on the Plantations." Joseph Corry, an Englishman who spent some time in what is now the West African nation of Sierra Leone, noted, "Rice forms the chief part of the African's sustenance."

When further observation noted the skill of Africans in this region in cultivating rice, Africans from the vicinity of Sierra Leone and Ghana became especially sought-after by slave owners in the South Carolina Lowcountry.

The demand for Africans in the rice-growing regions was such that, "By the time the (South Carolina) colony's Proprietors gave way to a royal government in 1720, Africans had outnumbered Europeans for more than a decade."

According to Elaine Nichols of the South Carolina State Museum, Sullivan's Island, an island near Charleston, was a major port of entry for enslaved Africans. Her paper "Sullivan's Island Pest Houses: Beginning an Archeological Investigation" (1989), detailed the phenomenon of "Pest Houses," that were used to quarantine Africans upon their arrival, for fear that the Africans would have contagious diseases. The Africans would often remain confined from 10 to 40 days and 200-300 at a time would sometimes remain in isolation in the "pest houses." By 1793, residents of Sullivan's Island demanded that the pest houses be removed from the vicinity. Three years later, the houses were sold and new ones were built on nearby James Island.

According to an undated pamphlet regarding Charleston's Old Slave Mart, one such market existed at the workhouse on Magazine Street, but was shut down in the 1850s. The sight of slave sales (if not the institution of slavery itself) proved to be offensive to many Charlestonians, and several ordinances forbade "the promiscuous selling" of enslaved Africans in public view. In 1859, the market at 6 Chalmers St. began to be used for the sale of enslaved Africans until the end of slavery, and it is this building that is referred to in Charleston as "The Old Slave Mart."

For many years, both blacks and whites in Charleston preferred to ignore this city's role in the slave trade. However, in 1999, John Leigh, Sierra Leone's ambassador to the United States, took part with local dignitaries in a ceremony commemorating Sullivan's Island's role as a major port of entry for enslaved Africans. A marker was erected near the site of the pest houses, and remembrance ceremonies are held during the month of June to commemorate the memory of the enslaved Africans at Sullivan's Island.

At least three names of the many enslaved Africans who entered through the Lowcountry are known today. One was Denmark Vesey, who was brought from St. Thomas after he was purchased by Capt. Joseph Vesey in the late 18th century. Denmark Vesey is best remembered as the planner of the unsuccessful Charleston Slave Rebellion of 1822, which led to the establishment of a military garrison to contain future slave rebellions. This garrison later became a military college known as The Citadel. Omar Ibn Said, a Senegalese Muslim captured into slavery, was also noted to have arrived in Charleston in 1807. Ajar, who was also captured from West Africa, was sold in Charleston in 1815. Ajar's son Tony, who was purchased by a man named Allen Little, was the great-grandfather of Malcolm Little, who is better known today as the African-American freedom fighter Malcolm X.

History

Colonial era (1670–1776)

After Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland (1630–1685) was restored to the English throne following Oliver Cromwell's Protectorate, he granted the chartered Carolina territory to eight of his loyal friends, known as the Lords Proprietors, in 1663. It took seven years before the Lords could arrange for settlement, the first being that of Charles Town. The community was established by English settlers under William Sayle in 1670 on the west bank of the Ashley River, a few miles northwest of the present city. It was soon chosen by Anthony Ashley-Cooper, one of the Lords Proprietors, to become a "great port towne," a destiny the city fulfilled. By 1680, the settlement had grown, joined by others from England, Barbados, and Virginia, and relocated to its current peninsular location. The capital of the Carolina colony, Charles Town was the center for further expansion and the southernmost point of English settlement during the late 17th century.

The settlement was often subject to attack from sea and from land. Periodic assaults from Spain and France, who still contested England's claims to the region, were combined with resistance from Native Americans, as well as pirate raids. While the earliest settlers primarily came from England, colonial Charleston was also home to a mixture of ethnic and religious groups. French, Scottish, Irish, and Germans migrated to the developing seacoast town, representing numerous Protestant denominations, as well as Roman Catholicism and Judaism. Sephardic Jews migrated to the city in such numbers that Charleston eventually was home to, by the beginning of the 19th century and until about 1830, the largest and wealthiest Jewish community in North America.[11] Africans were brought to Charleston on the Middle Passage, first as servants, then as slaves, especially Wolof, Yoruba, Fulani, Igbo, Malinke, and other peoples of the Windward Coast.[12] The port of Charleston was the main dropping point for Africans captured and transported to the United States for sale as slaves.

By the mid-18th century Charleston had become a bustling trade center, the hub of the Atlantic trade for the southern colonies, and the wealthiest and largest city south of Philadelphia. By 1770 it was the fourth largest port in the colonies, after only Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, with a population of 11,000, slightly more than half of that slaves.

Charleston was the hub of the deerskin trade. In fact, deerskin trade was the basis of Charleston's early economy. Trade alliances with the Cherokee and Creek insured a steady supply of deer hides. Between 1699 and 1715, an average of 54,000 deer skins were exported annually to Europe through Charleston. Between 1739 and 1761, the height of the deerskin trade era, an estimated 500,000 to 1,250,000 deer were slaughtered. During the same period, Charleston records show an export of 5,239,350 pounds of deer skins. Deer skins were used in the production of men's fashionable and practical buckskin pantaloons for riding, gloves, and book bindings.

Colonial low-country landowners experimented with cash crops ranging from tea to silk. African slaves brought knowledge of rice cultivation, which plantation owners made into a successful business by 1700.[13] With the help of African slaves from the Caribbean, Eliza Lucas, daughter of plantation owner George Lucas, learned how to raise and use indigo in the Low-Country in 1747. Supported with subsidies from Britain, indigo was a leading export by 1750.[14] Those and naval stores were exported in an extremely profitable shipping industry.

As Charleston grew, so did the community's cultural and social opportunities, especially for the elite merchants and planters. The first theater building in America was built in Charleston in 1736. Benevolent societies were formed by several different ethnic groups. The Charleston Library Society was established in 1748 by some wealthy Charlestonians who wished to keep up with the scientific and philosophical issues of the day. This group also helped establish the College of Charleston in 1770, the oldest college in South Carolina and the oldest municipally supported college in the United States.

American Revolution (1776–1785)

As the relationship between the colonists and Britain deteriorated, Charleston became a focal point in the ensuing American Revolution. It was twice the target of British attacks. At every stage the British strategy assumed a large base of Loyalist supporters who would rally to the King given some military support.[15]

In late March 1776, South Carolina President and Commander in Chief John Rutledge learned that a large British naval force was moving toward Charleston. To help defend the city, he ordered the construction of Fort Sullivan, on Sullivan's Island in the harbor. He then placed Col. William Moultrie in charge of the construction and made him the fort's commanding officer.

On June 28, 1776 General Henry Clinton with 2,000 men and a naval squadron tried to seize Charleston, hoping for a simultaneous Loyalist uprising in South Carolina. When the fleet fired cannonballs, the explosives failed to penetrate Fort Sullivan's unfinished, yet thick palmetto log walls. Additionally, no local Loyalists attacked the town from behind as the British had hoped. Col. Moultries' men were able to return fire and inflicted heavy damage on several of the British ships. The British were forced to withdraw their forces, and the fort was renamed Fort Moultrie in honor of its commander.

This battle kept Charleston safe from conquest for four years, and therefore was perceived as so symbolic of the Revolution that it spawned a number of key icons of South Carolina and the revolution:

During the battle, the flag Moultrie had flown in the battle (which he'd designed, himself) was shot down. It was then hoisted into the air again by Sargent William Jasper and kept aloft, rallying the troops, until it could be remounted. This Liberty Flag was seen as so important that it became the Flag of South Carolina, with the addition of the very palmetto tree that was used to make the fort so impenetrable.

The day of that battle is now a holiday in the state, known as Carolina Day.

Clinton returned in 1780 with 14,000 soldiers. American General Benjamin Lincoln was trapped and surrendered his entire 5400 men force after a long fight, and the Siege of Charleston was the greatest American defeat of the war. Several Americans escaped the carnage, and joined up with several militias, including those of Francis Marion, the 'Swampfox', and Andrew Pickens. The British retained control of the city until December 1782. After the British left the city's name was officially changed to Charleston in 1783, naming it after King Charles II of England.[16]

When the city was freed from the British, General Nathaniel Green presented its leaders with the Moultrie Flag, describing it as the first American flag flown in the South.

Antebellum era (1785–1861)

Although the city would lose the status of state capital to Columbia, Charleston became even more prosperous in the plantation-dominated economy of the post-Revolutionary years. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 revolutionized this crop's production, and it quickly became South Carolina's major export. Cotton plantations relied heavily on slave labor. Slaves were also the primary labor force within the city, working as domestics, artisans, market workers or laborers. By 1820 Charleston's population had grown to 23,000, with a black majority. When a massive slave revolt planned by Denmark Vesey, a free black, was discovered in 1822, such hysteria ensued amidst white Charlestonians and Carolinians that the activities of free blacks and slaves were severely restricted.

As Charleston's government, society and industry grew, commercial institutions were established to support the community's aspirations. The Bank of South Carolina, the second oldest building constructed as a bank in the nation, was established here in 1798. Branches of the First and Second Bank of the United States were also located in Charleston in 1800 and 1817. By 1840, the Market Hall and Sheds, where fresh meat and produce were brought daily, became the commercial hub of the city. The slave trade also depended on the port of Charleston, where ships could be unloaded and the slaves sold at markets.

In the first half of the 19th century, South Carolinians became more devoted to the idea that state's rights were superior to the Federal government's authority. In 1832 South Carolina passed an ordinance of nullification, a procedure in which a state could in effect repeal a Federal law, directed against the most recent tariff acts. Soon Federal soldiers were dispensed to Charleston's forts and began to collect tariffs by force. A compromise was reached that would gradually reduce the tariffs, but the underlying argument over state's rights escalated in the coming decades.

Civil War (1861–1865)

On December 20, 1860, following the election of Abraham Lincoln, the South Carolina General Assembly voted to secede from the Union. On January 9, 1861, Citadel cadets opened fire on the Union ship Star of the West entering Charleston's harbor. On April 12, 1861, shore batteries under the command of General Pierre G. T. Beauregard opened fire on the Union-held Fort Sumter in the harbor. After a 34-hour bombardment, Major Robert Anderson surrendered the fort, thus starting the war.

Union forces repeatedly bombarded the city, causing vast damage, and kept up a blockade that shut down most commercial traffic, although some blockade runners got through.[17] In a failed effort to break the blockade on February 17, 1864, an early submarine, the H.L. Hunley made a night attack on the USS Housatonic.[18]

In 1865, Union troops moved into the city, and took control of many sites, including the United States Arsenal, which the Confederate Army had seized at the outbreak of the war. The War Department also confiscated the grounds and buildings of the Citadel Military Academy, and used this as a federal garrison for over seventeen years. It was finally returned to the state and reopened as a military college in 1882 under the direction of Lawrence E. Marichak.

Postbellum era (1865–1945)

After the defeat of the Confederacy, Federal forces remained in Charleston during the city's reconstruction. The war had shattered the prosperity of the antebellum city. Freed slaves were faced with poverty and discrimination. Industries slowly brought the city and its inhabitants back to a renewed vitality and growth in population. As the city's commerce improved, Charlestonians also worked to restore their community institutions. In 1865 The Avery Normal Institute was established by the American Missionary Association as a private school for Charleston's African American population. General William T. Sherman lent his support to the conversion of the United States Arsenal into the Porter Military Academy, an educational facility for former soldiers and boys left orphaned or destitute by the war. Porter Military Academy later joined with Gaud School and is now a prep school, Porter-Gaud School. The William Enston Homes, a planned community for the city's aged and infirm, was built in 1889. J. Taylor Pearson, a freed slave, designed the Homes, and passed peacefully in them after years as the maintenance manager post-reconstruction. An elaborate public building, the United States Post Office and Courthouse, was completed in 1896 and signaled renewed life in the heart of the city.

On August 31, 1886, Charleston was nearly destroyed by an earthquake measuring 7.3 on the Richter scale. It was felt as far away as Boston, Massachusetts to the north, Chicago, Illinois and Milwaukee, Wisconsin to the northwest, as far west as New Orleans, Louisiana as far south as Cuba, and as far east as Bermuda. It damaged 2,000 buildings in Charleston and caused $6 million worth of damage ($133 million (2006 USD)), while in the whole city the buildings were only valued at approximately $24 million($531 million(2006 USD).

Contemporary era (1945–present)

Charleston languished economically for several decades in the 20th century, though the large military presence in the region helped to shore up the city's economy. The Charleston Hospital Strike of 1969 was one of the last major events of the civil rights movement and brought Ralph Abernathy, Coretta Scott King, Andrew Young and other prominent figures to march with the local leader Mary Moultrie. Its story is told in Tom Dent's book "Southern Journey." Joseph P. Riley, Jr. was elected as mayor in the 1970s, and helped advance several cultural aspects of the city. Riley has been the major proponent of reviving Charleston's economic and cultural heritage. The last thirty years of the 20th century saw major new reinvestment in the city, with a number of municipal improvements and a commitment to historic preservation. These commitments were not slowed down by Hurricane Hugo and continue to this day. The eye of Hurricane Hugo came ashore at Charleston Harbor in 1989, and though the worst damage was in nearby McClellanville, three-quarters of the homes in Charleston's historic district sustained damage of varying degree. The hurricane caused over $2.8 billion in damage. The city was able to rebound fairly quickly after the hurricane and has grown in population, reaching an estimated 124,593 residents in 2009.[19]

Geography

The city proper consists of six distinct areas: the Peninsula/Downtown, West Ashley, Johns Island, James Island, Daniel Island, and the Cainhoy Peninsula.

Topography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 347.5 square kilometers (134.2 sq mi), of which 251.2 square kilometres (97.0 sq mi) is land and 44.3 square kilometres (17.1 sq mi) is water. The old city is located on a peninsula at the point where, as Charlestonians say, "The Ashley and the Cooper Rivers come together to form the Atlantic Ocean." The entire peninsula is very low, some is landfill material, and as such, frequently floods during heavy rains, storm surges and unusually high tides. The city limits have expanded across the Ashley River from the peninsula, encompassing the majority of West Ashley as well as James Island and some of Johns Island. The city limits also have expanded across the Cooper River, encompassing Daniel Island and the Cainhoy area. North Charleston blocks any expansion up the peninsula, and Mount Pleasant occupies the land directly east of the Cooper River.

The tidal rivers (Wando, Cooper, Stono, and Ashley) are evidence of a submergent or drowned coastline. There is a submerged river delta off the mouth of the harbor, and the Cooper River is deep, affording a good location for a port. The rising of the ocean may be due to melting of glacial ice during the end of the Ice Age.

Climate

Charleston has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with mild winters, hot, humid summers, and significant rainfall all year long. Summer is the wettest season; almost half of the annual rainfall occurs during the summer months in the form of thundershowers. Fall remains relatively warm through November. Winter is short and mild, and is characterized by occasional rain. Snow flurries seldom occur, although in 2010, 3.4 inches (8.6 cm) fell on the evening of February 12, the heaviest in 20 years. The highest temperature recorded (inside city limits at the Customs House on E. Bay St.) was 104 °F (40 °C), on June 2, 1985, and the lowest temperature recorded was 10 °F (−12 °C) on January 21, 1985.[20] Hurricanes are a major threat to the area during the summer and early fall, with several severe hurricanes hitting the area – most notably Hurricane Hugo on September 21, 1989 (a Category 4 storm).

Charleston was hit by a large tornado in 1761, which temporarily emptied the Ashley River, and sank five offshore warships.[21]

| Climate data for Charleston, South Carolina (Airport), 1981-2010 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 59.0 (15.0) |

62.8 (17.1) |

69.6 (20.9) |

76.5 (24.7) |

83.2 (28.4) |

88.4 (31.3) |

91.1 (32.8) |

89.6 (32.0) |

84.9 (29.4) |

77.1 (25.1) |

69.8 (21.0) |

61.6 (16.4) |

76.1 (24.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 38.1 (3.4) |

41.2 (5.1) |

47.2 (8.4) |

53.8 (12.1) |

62.4 (16.9) |

70.2 (21.2) |

73.6 (23.1) |

72.9 (22.7) |

67.8 (19.9) |

57.3 (14.1) |

48.1 (8.9) |

40.6 (4.8) |

56.1 (13.4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.70 (94) |

2.96 (75) |

3.71 (94) |

2.91 (74) |

3.02 (77) |

5.64 (143) |

6.52 (166) |

7.15 (182) |

6.10 (155) |

3.75 (95) |

2.43 (62) |

3.11 (79) |

50.99 (1,295) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.1 (0.25) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.6 (1.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.5 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 11.9 | 13.0 | 13.2 | 10.0 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 112.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 179.8 | 189.3 | 244.9 | 276.0 | 294.5 | 279.0 | 288.3 | 257.3 | 219.0 | 223.2 | 189.0 | 170.5 | 2,810.8 |

| Source: NOAA [22] HKO [23] | |||||||||||||

Metropolitan Statistical Area

The Charleston-North Charleston-Summerville Metropolitan Statistical Area currently consists of three counties: Charleston, Berkeley, and Dorchester. As of the 2010 U.S. Census, the metropolitan statistical area had a total population of about 664,607 people. North Charleston is the second largest city in the Charleston-North Charleston-Summerville Metropolitan Statistical Area and ranks as the third largest city in the state; Mount Pleasant and Summerville are the next largest cities. These cities combined with other incorporated and unincorporated areas surrounding the city of Charleston form the Charleston-North Charleston Urban Area with a population of 548,404 as of 2010.[24] The metropolitan statistical area also includes a separate and much smaller urban area within Berkeley County, Moncks Corner (with a 2000 population of 9,123).

The traditional parish system persisted until the Reconstruction, when counties were imposed. Nevertheless, traditional parishes still exist in various capacities, mainly as public service districts. The city of Charleston proper, which was originally defined by the limits of the Parish of St. Philip & St. Michael. It now also includes parts of St. James' Parish, St. George's Parish, St. Andrew's Parish, and St. John's Parish, although the last two are mostly still incorporated rural parishes.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 16,359 | — | |

| 1800 | 18,824 | 15.1% | |

| 1810 | 24,711 | 31.3% | |

| 1820 | 24,780 | 0.3% | |

| 1830 | 30,289 | 22.2% | |

| 1840 | 29,261 | −3.4% | |

| 1850 | 42,985 | 46.9% | |

| 1860 | 40,522 | −5.7% | |

| 1870 | 48,956 | 20.8% | |

| 1880 | 49,984 | 2.1% | |

| 1890 | 54,955 | 9.9% | |

| 1900 | 55,807 | 1.6% | |

| 1910 | 58,833 | 5.4% | |

| 1920 | 67,957 | 15.5% | |

| 1930 | 62,265 | −8.4% | |

| 1940 | 71,275 | 14.5% | |

| 1950 | 70,174 | −1.5% | |

| 1960 | 60,288 | −14.1% | |

| 1970 | 66,945 | 11.0% | |

| 1980 | 69,779 | 4.2% | |

| 1990 | 80,414 | 15.2% | |

| 2000 | 96,650 | 20.2% | |

| 2010 | 120,083 | 24.2% | |

| 2011 (est.) | 122,689 | 2.2% | |

2011 estimate | |||

The racial/ethnic makeup of Charleston is 52.2% White, 41.1% African American, 1.6% Asian, and 4.4% are Hispanic and Latinos of any race.[25]

Government

Charleston has a strong mayor-council government, with the mayor acting as the chief administrator and the executive officer of the municipality. The mayor also presides over city council meetings and has a vote, the same as other council members. The current mayor, since 1975, is Joseph P. Riley, Jr. The council has twelve members who are elected from one of twelve districts.

The city's voters are among the most liberal in South Carolina. In 2006, Charleston's residents voted against Amendment 1, which sought to ban same-sex marriage in South Carolina. Statewide, the measure passed by 78% to 22% but the voters of Charleston rejected it by 3,563 (52%) to 3,353 votes (48%).[26]

Emergency services

Fire department

The City of Charleston Fire Department consists over 300 full time firefighters. These firefighters operate out of nineteen companies located throughout the city: sixteen engine companies, two tower companies, and one ladder company. Training, Fire Marshall, Operations, and Administration are the divisions of the department. [27] The department operates on a 24/48 schedule and had a Class 1 ISO rating until late 2008, when ISO officially lowered it to Class 3.[28] Russell (Rusty) Thomas served as Fire Chief until June 2008, and was succeeded by Chief Thomas Carr in November 2008.

Police department

The City of Charleston Police Department, with a total of 412 sworn officers, 137 civilians and 27 reserve police officers, is South Carolina's largest police department.[2] Their procedures on cracking down on drug use and gang violence in the city are used as models to other cities to do the same.[citation needed] According to the final 2005 FBI Crime Reports, Charleston crime level is worse than the national average in almost every major category.[29] Greg Mullen, the former Deputy Chief of Police in the City of Virginia Beach, Virginia, serves as the current police chief. The former Charleston police chief was Reuben Greenberg who resigned August 12, 2005. Greenberg was credited with creating a polite police force that kept police brutality well in check, even as it developed a visible presence in community policing and a significant reduction in crime rates.[30]

EMS and medical centers

Emergency medical services for the city are provided by Charleston County Emergency Medical Services (CCEMS) & Berkeley County Emergency Medical Services (BCEMS). The city is served by both Charleston & Berkeley counties EMS and 911 services since the city is part of both counties.

Charleston is the primary medical center for the eastern portion of the state. The city has several major hospitals located in the downtown area: Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center (MUSC), Ralph H. Johnson VA Medical Center, and Roper Hospital. MUSC is the state's first school of medicine, the largest medical university in the state, and the sixth oldest continually operating school of medicine in the United States. The downtown medical district is experiencing rapid growth of biotechnology and medical research industries coupled with substantial expansions of all the major hospitals. Additionally, more expansions are planned or underway at another major hospital located in the West Ashley portion of the city: Bon Secours-St Francis Xavier Hospital. The Trident Regional Medical Center located in the City of North Charleston and East Cooper Regional Medical Center located in Mount Pleasant also serve the needs of residents of the City of Charleston.

Crime

The following table shows Charleston's crime rate in six crimes that Morgan Quitno uses for their calculation for "America's most dangerous cities" ranking, in comparison to the national average. The statistics provided are not for the actual number of crimes committed, but how many crimes committed per 100,000 people.[31]

| Crime | Charleston, South Carolina (2007) | National Average |

|---|---|---|

| Murder | 12.8 | 6.9 |

| Rape | 50.3 | 32.2 |

| Robbery | 244.1 | 195.4 |

| Assault | 515.6 | 340.1 |

| Burglary | 676.5 | 814.5 |

| Automobile Theft | 1253.8 | 391.3 |

Since 1999, the overall crime rate of Charleston has begun to decline. The total crime index rate for 1999 was 597.1 crimes committed per 100,000 people. the United States Average is 320.9 per 100,000. Charleston had a total crime index rate of 430.9 per 100,000 for the year of 2007.

According to the Congressional Quarterly Press 2008 City Crime Rankings: Crime in Metropolitan America, Charleston, South Carolina ranks as the 124th most dangerous city larger than 75,000 inhabitants.[32][33] However, the entire Charleston-North Charleston-Summerville Metropolitan Statistical Area had a much higher overall crime rate, ranking at #21.[34]

Infrastructure and economy

Economic sectors and major employers

Charleston is a major tourist destination, with a considerable number of luxury hotels, hotel chains, inns, and bed and breakfasts and a large number of award-winning restaurants and quality shopping. The city has two shipping terminals, owned and operated by the South Carolina Ports Authority, which are part of the fourth largest container seaport on the East Coast and the thirteenth largest container seaport in North America in 2009.[35] Piggly Wiggly Carolina Company, a grocery store chain with stores in South Carolina and Georgia, is headquartered in the city. Charleston is becoming a prime location for information technology jobs and corporations, most notably Blackbaud, Modulant, CSS and Benefitfocus. Higher education is also an important sector in the local economy, with institutions such as the Medical University of South Carolina, College of Charleston, The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina, and Charleston School of Law. Charleston is also an important art destination, named a top 25 arts destination by AmericanStyle magazine.[36]

U.S.P.S. zip codes

The City of Charleston is served by these Zip Codes:[37]

- 29401

- 29403

- 29405

- 29406 – This zip code is incorrectly listed by U.S.P.S. as serving the City of Charleston. It only serves the City of North Charleston[38][39]

- 29407

- 29409 - This zip code serves the campus of The Citadel, which has its own post office and mail system.

- 29412

- 29414

- 29424 - This zip code serves the campus of The College of Charleston, which has its own post office and mail system.

- 29425 - This zip code serves the Medical University of South Carolina, which has its own post office and mail system.

- 29455

- 29492

Transportation

Airport

Charleston is served by the Charleston International Airport, which is located in the City of North Charleston (IATA: CHS, ICAO: KCHS) and is the busiest passenger airport in the state of South Carolina. The airport shares runways with the adjacent Charleston Air Force Base. Charleston Executive Airport is a smaller airport located in the John's Island section of the City of Charleston and is used by non-commercial aircraft. Both airports are owned and operated by the Charleston County Aviation Authority.

Interstates and highways

Interstate 26 enters the city from the northwest and connects the city to North Charleston, the Charleston International Airport, Interstate 95, and Columbia, South Carolina. It ends in downtown Charleston with exits to the Septima Clark Expressway, the Arthur Ravenel, Jr. Bridge and Meeting Street. The Arthur Ravenel, Jr. Bridge and Septima Clark Expressway are part of U.S. Highway 17, which travels east-west through the cities of Charleston and Mount Pleasant. The Mark Clark Expressway, or Interstate 526, is the bypass around the city and begins at U.S. Highway 17 North/South. U.S. Highway 52 is Meeting Street and its spur is East Bay Street, which becomes Morrison Drive after leaving the Eastside. This highway merges with King Street in the city's Neck area (Industrial District). U.S. Highway 78 is King Street in the downtown area, eventually merging with Meeting Street.

Major highways

I-26 (Interstate 26) (Eastern terminus is in Charleston)

I-26 (Interstate 26) (Eastern terminus is in Charleston) I-526 (Interstate 526)

I-526 (Interstate 526) I-526 BS (Business Spur 526) – Mount Pleasant

I-526 BS (Business Spur 526) – Mount Pleasant US 17 (U.S. Route 17)

US 17 (U.S. Route 17) US 52 (U.S. Route 52) (Eastern terminus is in Charleston)

US 52 (U.S. Route 52) (Eastern terminus is in Charleston)- Lua error in Module:Jct at line 204: attempt to concatenate local 'link' (a nil value).

US 78 (U.S. Route 78) (Eastern terminus is in Charleston)

US 78 (U.S. Route 78) (Eastern terminus is in Charleston) SC 7 – Sam Rittenberg Boulevard

SC 7 – Sam Rittenberg Boulevard SC 30 – James Island Expressway

SC 30 – James Island Expressway SC 61 – St. Andrews Boulevard/Ashley River Road

SC 61 – St. Andrews Boulevard/Ashley River Road SC 171 – Old Towne Road/Folly Road

SC 171 – Old Towne Road/Folly Road SC 461 – Paul Cantrell Boulevard/Glenn McConnell Parkway

SC 461 – Paul Cantrell Boulevard/Glenn McConnell Parkway SC 700 – Maybank Highway

SC 700 – Maybank Highway

Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge

The Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge across the Cooper River opened on July 16, 2005, and was the second longest cable-stayed bridge in the Americas at the time of its construction.[citation needed] The bridge links Mount Pleasant with downtown Charleston, and has eight lanes and a 12-foot lane shared by pedestrians and bicycles. It replaced the Grace Memorial Bridge (built in 1929) and the Silas N. Pearman Bridge (built in 1966). They were considered two of the more dangerous bridges in America and were demolished after the Ravenel Bridge opened.

Charleston Area Regional Transportation Authority

The city is also served by a bus system, operated by the Charleston Area Regional Transportation Authority (CARTA). The majority of the urban area is served by regional fixed route buses, which are equipped with bike racks as part of the system's Rack & Ride program. CARTA offers connectivity to historic downtown attractions and accommodations with DASH (Downtown Area Shuttle) trolley buses, and it offers curbside pickup for disabled passengers with its Tel-A-Ride buses.

Rural parts of the city and metropolitan area are served by a different bus system, operated by Berkeley-Charleston-Dorchester Rural Transportation Management Association (BCD-RTMA). The system is also commonly called the TriCounty Link.[40]

Port

The Port of Charleston, owned and operated by the South Carolina Ports Authority, is one of the largest ports in the U.S. The Port of Charleston consists of five terminals. Despite occasional labor disputes, the port is ranked number one in customer satisfaction across North America by supply chain executives.[41] Port activity at the two terminals located in the City of Charleston, is one of the city's leading sources of revenue, behind tourism.

Today the Port of Charleston boasts the deepest water in the Southeast region and regularly handles ships too big to transit through the Panama Canal. A next-generation harbor deepening project is currently underway to take the Port of Charleston's shipping channel deeper than 45 feet at mean low tide.

Union Pier, in the City of Charleston, also includes a cruise ship passenger terminal and hosts numerous cruise departures annually. In May 2010, the Carnival Fantasy was permanently stationed in Charleston, offering weekly cruises to the Bahamas and Key West, eventually to include Bermuda. With the addition of the weekly Carnival Fantasy sailings, Union Terminal hosted 67 embarkations and ports of call in 2010.

Terminals

- Wando Welch Terminal – used for container cargo. Located in the Town of Mount Pleasant.

- Columbus Street Terminal – used for project cargo, breakbulk and roll-on/roll-off cargo. Located in the City of Charleston.

- Union Pier Terminal – used for cruise ship operations originating in the city. Located in the City of Charleston.

- North Charleston Terminal – used for container cargo. Located in the City of North Charleston.

- Veterans Terminal – used for project cargo, break-bulk and roll-on/roll-off cargo. Located in the City of North Charleston.

Rail transport

The Amtrak station, located in the City of North Charleston, is served by two Amtrak trains, the Palmetto and the Silver Meteor, operating between New York and Savannah, Georgia and Miami, Florida, respectively.[42]

Culture

Charleston is well-known across the United States and beyond for its unique culture, which blends traditional Southern American, English, French, and West African elements. The downtown peninsula is well known for its prominence of art, music, local cuisine, and fashion. Spoleto Festival USA, held annually in late spring, is one of the world's major performing arts festivals. It was founded in 1977 by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Gian Carlo Menotti, who sought to establish a counterpart to the Festival dei Due Mondi (the Festival of Two Worlds) in Spoleto, Italy. Charleston's oldest community theater group, the Footlight Players, has provided theatrical productions of a high quality since 1931. A variety of performing arts venues includes the historic Dock Street Theatre. The annual Charleston Fashion Week held each Spring in Marion Square brings in designers, journalists, and clients from across the Nation. Charleston is well known for its local seafood, which plays a key role in the city's renowned cuisine, comprising staple dishes such as Gumbo, She-Crab Soup, Fried Oysters, Lowcountry Boil, Deviled Crab Cakes, Red Rice, and Shrimp and Grits. The culture in Charleston differs greatly even from the rest of South Carolina, with British and French elements heavily prevalent. Downtown, horse-drawn carriages share the cobblestone streets with cars. Tourism is among the main contributors to a strong local economy, as Charleston is annually among the nation's most visited cities, as well as being an enormously popular wedding destination. The city is the site of several significant historical sites pertaining to both the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, including Fort Sumter, where the first shots of the Civil War were fired by Charlestonian Confederate soldiers.

Dialect

Charleston's unique dialect has long been noted in the South and elsewhere for its singular attributes. Alone among the various regional Southern accents, the Charleston accent traditionally has ingliding or monophthongal long mid-vowels, raises ay and aw in certain environments, and is non-rhotic (although non-rhoticity was definitely not unique to Charleston and some or all of the above features may not have been either). Some attribute these unique features of Charleston's speech to its early settlement by the French Huguenots and Sephardic Jews, both of which played influential parts in Charleston's development and history. However, given Charleston's high concentration of African-Americans that spoke the Gullah language, the speech patterns probably were more influenced by the dialect of the Gullah African-American community.

The "Charleston accent" can be particularly noted in the local pronunciation of the city's name itself. A Charleston native will typically ignore the r, elongate the middle vowel, and shorten the ending vowel, pronouncing the name as "Ch-\aw\lst-un."

Today, the Geechee language and dialect is still spoken among African-American locals. However, rapid development, especially on the surrounding sea islands, is slowly diminishing its prominence.

Two important works shed light on Charleston's early dialect: Charleston Provincialisms and The Huguenot Element in Charleston's Provincialisms, both by Sylvester Primer. Further scholarship is needed on possible influence of Sephardic Jews on Charleston speech patterns.

Religion

Charleston, known as the "Holy City" [43] has long been noted for its numerous churches and denominations. It is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston, the seventh oldest diocese in the United States. The well noted Bishop John England, D.D. was the first Roman Catholic Bishop of this city, and the private Bishop England High School was named in his honor. The city's oldest Roman Catholic parish, Saint Mary of the Annunciation Roman Catholic Church, is the mother church of Roman Catholicism to North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. It is also the Seat of the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina. The city is home to one of two remaining Huguenot churches in America, the only one that is still a Protestant congregation.[44] The city is home to many well known churches, cathedrals and synagogues. The churchtower spotted skyline is one of the reasons for the city's nickname, "The Holy City." The tallest church in South Carolina and the tallest building in Charleston is St. Matthew's German Evangelical Lutheran Church. Historically, Charleston was one of the most religiously tolerant cities in the New World. Recently, the conservative Episcopal diocese of South Carolina, headquartered in Charleston, has been one of the key players in potential schism in the Anglican Communion. Charleston is home to the only African-American Seventh Day Baptist Church congregation in the Seventh Day Baptist General Conference of the United States and Canada. The First Baptist Church of Charleston (1682) is the oldest Baptist church in the South and the first Southern Baptist Church in existence. It is also used as a private K-12 school. Charleston also has a large and historic Jewish population. The American branch of the Reform Jewish movement was founded in Charleston at Synagogue Congregation Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim. It is the fourth oldest Jewish congregation in the continental United States (after New York, Newport and Savannah).

|

|

|

|

Annual cultural events and fairs

Charleston annually hosts Spoleto Festival USA founded by Gian Carlo Menotti, a 17-day art festival featuring over 100 performances by individual artists in a variety of disciplines. The Spoleto Festival is internationally recognized as America's premier performing arts festival.[45] The annual Piccolo Spoleto festival takes place at the same time, and features local performers and artists, with hundreds of performances throughout the city. Other notable festivals and events include the Taste of Charleston, The Lowcountry Oyster Festival, the Cooper River Bridge Run, Southeastern Wildlife Exposition (SEWE), Charleston Food and Wine Festival, Charleston Fashion Wk, and the MOJA Arts Festival, and the Holiday Festival of Lights (at James Island County Park).

Live theater

Charleston has a vibrant theater scene, and is home to America's first theater. In 2010 Charleston was listed as one of the country's top 10 cities for theater, and one of the top 2 in the South.[46] Most of the theaters are part of the League of Charleston Theatres, better known as Theatre Charleston [3] . Some of the city's theaters include:

- The Dock Street Theatre – America's first theater. Home of the Charleston Stage Company, South Carolina's largest professional theater company.

- The Village Playhouse – A nationally recognized professional theater company east of the Cooper River.

- The Footlight Players – One of the leading community theaters in the South.[47]

- Theatre 99 – An improvisational theater company.

- Pure Theatre – A small professional theater that produces contemporary plays.

- Sottile Theatre, on the campus of The College of Charleston

- The Black Fedora Comedy Mystery Theatre – Clean comedy whodunits with volunteer audience participation.[48]

Museums, historical sites and other attractions

Charleston has many historic buildings, art and historical museums, and other attractions, including:

- The Calhoun Mansion is a 24,000 square foot, 1876 Victorian home at 16 Meeting Street, named for a grandson of John C. Calhoun who lived there with his wife, the builder's daughter. The private house is periodically open for tours.

- The Charleston Museum, America's First Museum, founded in 1773. Its mission is to preserve and interpret the cultural and natural history of Charleston and the South Carolina Lowcountry.

- The Exchange and Provost was built in 1767. The building features a dungeon that held various signers of the Declaration of Independence and hosted events for George Washington in 1791 and the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1788. It is operated as a museum by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

- The Powder Magazine is a 1713 gunpowder magazine and museum. It is the oldest surviving public building in South Carolina.

- The Gibbes Museum of Art opened in 1905 and houses a premier collection of principally American works with a Charleston or Southern connection.

- The Fireproof Building houses the South Carolina Historical Society, a membership-based reference library open to the public.

- The Nathaniel Russell House is an important Federal style house. It is owned by the Historic Charleston Foundation and open to the public as a house museum.

- The Gov. William Aiken House, also known as the Aiken-Rhett House is a home built in 1820 for William Aiken, Jr.

- The Heyward-Washington House is a historic house museum owned and operated by the Charleston Museum. Furnished for the late 18th century, the house includes a collection of Charleston-made furniture.

- The Joseph Manigault House is a historic house museum owned and operated by the Charleston Museum. The house was designed by Gabriel Manigault and is significant for its Adam style architecture.

- The Market Hall and Sheds, also known as the City Market or simply the Market, stretch several blocks behind 188 Meeting Street. Market Hall was built in the 1841 and houses the Daughters of the Confederacy Museum. The sheds house some permanent stores but are mainly occupied by open-air vendors.

- The Avery Research Center For African-American History and Culture was established to collect, preserve, and make public the unique historical and cultural heritage of African Americans in Charleston and the South Carolina Lowcountry. Avery's archival collections, museum exhibitions, and public programming reflect these diverse populations as well as the wider African Diaspora.

- South Carolina Aquarium

- Fort Sumter, site of the first shots fired in the Civil War.

- The Battery is an historic defensive seawall and promenade located at the tip of the peninsula along with White Point Garden, a park featuring several memorials and Civil War-era artillery pieces.

- Rainbow Row is an iconic strip of homes along the harbor that date back to the mid-18th century. Though the homes themselves are not open to the public, they are one of the most photographed attractions in the city and are featured heavily in local art.[49]

Sports

Charleston is home to a number of professional, minor league, and amateur sports teams:

- The Charleston Battery, a professional soccer team, plays in the USL Professional Division. The Charleston Battery play on Daniel Island at Blackbaud Stadium.

- The Charleston RiverDogs, a Minor League Baseball team, play in the South Atlantic League, and are an affiliate of the New York Yankees. The RiverDogs play at Joseph P. Riley, Jr. Park.

- The Charleston Outlaws RFC is a Rugby Union Football Club founded in 1973. The Club is in good standing with the Palmetto Rugby Union, USA Rugby South, and USARFU. The club competes for honors in Men's Division II against the Cape Fear, Columbia, Greenville, and Charlotte "B" clubs. The club also hosts a Rugby Sevens tournament during Memorial Day weekend.

Other notable sports venues in Charleston include Johnson Hagood Stadium (home of The Citadel Bulldogs football team) and Toronto Dominion Bank Arena at the College of Charleston, which seats 5,700 people for the school's basketball and volleyball teams.

Fiction

Charleston is a popular filming location for movies and television, both in its own right and as a stand-in for southern and/or historic settings. For a list of both, see here. In addition, many novels, plays, and other works of fiction have been set in Charleston, including the following:

- Several books by Citadel alumnus and novelist Pat Conroy, such as The Lords of Discipline (based on Conroy's experiences as a cadet at The Citadel) and South of Broad.

- The Gullah opera Porgy and Bess

- Clive Barker's novel Galilee

- Harry Turtledove's Southern Victory Series alternate history series about a Confederacy that won the Civil War

- Rafael Sabatini's novel The Carolinian

- The 1991 bestseller Scarlett, sequel to Gone with the Wind. In fact, Alexandra Ripley, the author of Scarlett, derived inspiration from the city for her novel Charleston and its sequel On Leaving Charleston.

- The Notebook, 2004, starring Rachel McAdams and Ryan Gosling, was filmed in Charleston. The American Theatre on King Street was Allie and Noah's first date spot.

- The Novel, Werewolf Smackdown by Mario Acevedo is set in Charleston[50]

- The novels Dreams of Sleep, Rich in Love and The Fireman's Fair were written by Josephine Humphreys, a native of Charleston. All are set in Charleston and the Charleston area. See the film entry for Rich in Love, which was filmed on Mount Pleasant and in Charleston.

- The 2010 film, Dear John.

- Gullah Gullah Island

- The College of Charleston's Cistern is featured in the 2000 movie The Patriot. It serves as the meeting house where the South Carolinians decide to join the fight against the British.

- Virals and Seizure by Kathy Reichs. The location of the books are set in Charleston.

Nearby cities and towns

|

|

Other outlying areas

- James Island

- Johns Island

- Wadmalaw Island

- Morris Island

- Edisto Island

- Dewee's Island

- Yonges Island

- Ladson

Parks

|

|

Schools, colleges and universities

Because most of the city of Charleston is located in Charleston County, it is served by the Charleston County School District. Part of the city, however, is served by the Berkeley County School District in northern portions of the city, such as the Cainhoy Industrial District, Cainhoy Historical District and Daniel Island.

Charleston is also served by a large number of independent schools, including Porter-Gaud School (K-12), Ashley Hall (K-12), Charleston Day School (K-8), First Baptist Church School (K-12), Palmetto Christian Academy (K-12), Coastal Christian Preparatory School (K-12), Mason Preparatory School (K-8), and Addlestone Hebrew Academy (K-8).

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston Office of Education also operates out of the city and oversees several K-8 parochial schools, such as Blessed Sacrament School, Christ Our King School, Charleston Catholic School, Nativity School, and Divine Redeemer School, all of which are "feeder" schools into Bishop England High School, a diocesan high school within the city. Bishop England, Porter-Gaud School, and Ashley Hall are the city's oldest and most prominent private schools, and are in themselves a significant part of Charleston history, dating back some 150 years.

Public institutions of higher education in Charleston include the College of Charleston (the nation's 13th oldest university), The Citadel (The Military College of South Carolina). The city is home to a law school, the Charleston School of Law, as well as a medical school, the Medical University of South Carolina. Charleston is also home to the Roper Hospital School of Practical Nursing, and the city has a downtown satellite campus for the region's technical school, Trident Technical College. Charleston is also the location for the only college in the country that offers bachelors degrees in the building arts, The American College of the Building Arts. The Art Institute of Charleston located downtown on North Market Street and opened in 2007.

Armed forces

Coast Guard

- Coast Guard Sector Charleston

- Coast Guard Station Charleston

Army

South Carolina Army National Guard

Media

Broadcast television

Charleston is the nation's 98th largest Designated market area (DMA), with 312,770 households and 0.27% of the U.S. TV population.[52] The following stations are licensed in Charleston and have significant operations or viewers in the city:[53]

- WCBD-TV (2, NBC, CW): licensed in Charleston, owned by Media General, studios in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina

- WCIV-TV (4, ABC): licensed in Charleston, (Allbritton Communications), studios in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina

- WCSC-TV (5, CBS, Ind., Bounce TV): licensed in Charleston; owned by Raycom, studios in Charleston, South Carolina

- WITV-TV (7, PBS): licensed in Charleston, owned by South Carolina Educational Television, transmitter in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina

- WLCN-CD (18, RTV) licensed in Charleston, owned by Faith Assembly of God, studios in Summerville, South Carolina

- WTAT-TV (24, Fox): licensed in Charleston, owned by Cunningham Broadcasting Company, studios in North Charleston, South Carolina

- WAZS-CD (29, Azteca America Independent) licensed in Charleston, owned by Jabar Communications, studios in North Charleston, South Carolina

- WJNI-CD (31, America One Independent) licensed in Charleston, owned by Jabar Communications, studios in North Charleston, South Carolina

- WMMP-TV (36, My Network Television, TheCoolTV): licensed in Charleston, owned by Sinclair Broadcasting Company, studios in North Charleston, South Carolina

Radio Stations

Sister cities

Charleston has one official sister city, Spoleto, Umbria, Italy.[54] The relationship between the two cities began when Pulitzer Prize-winning Italian composer Gian Carlo Menotti selected Charleston as the city to host the American version of Spoleto's annual Festival of Two Worlds. "Looking for a city that would provide the charm of Spoleto as well as its wealth of theaters, churches and other performance spaces, they selected Charleston, South Carolina as the ideal location. The historic city provided a perfect fit: intimate enough that the Festival would captivate the entire city, yet cosmopolitan enough to provide an enthusiastic audience and robust infrastructure."[45]

Charleston is also twinned with Speightstown, St. Peter, Barbados.[55] The original parts of Charlestown were based on the plans of Barbados's capital city Bridgetown.[56] Many dispossessed indigo, tobacco and cotton planters departed from Speightstown, along with their slaves, and helped found Charleston after there was a wholesale move to adopt sugar cane cultivation in Barbados; a land and labor-intensive enterprise that helped usher in the era of Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade in the former British West Indies.[57]

See also

- Charleston Historic District

- Old Slave Mart

- Charleston Sofa Super Store fire

- The Citadel

- College of Charleston

- Christopher Werner

- Daniel Island

- Dewees Island

- French Quarter (Charleston, South Carolina)

- Gullah

- Hampton Park Terrace

- History of the Jews in Charleston, South Carolina

- John Henry Devereux

- Hurricane Hugo

- List of people from Charleston, South Carolina

- List of tallest buildings in Charleston, South Carolina

- List of television shows and movies in Charleston, South Carolina

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Charleston, South Carolina

- Riverland Terrace

- West Ashley

Notes

- ^ "2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ "Charleston Time Line". Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ^ "Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1840".

- ^ Perry, Lee Davis; McLaughlin, J. Michael (2007) [1999]. Inisders Guide to Charleston (google books) (Eleventh ed.). Guilford, CN: Morris Book Publishing. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-7627-4403-9. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ Rosen, Robert N. (1992) [1982]. A Short History of Charleston (Google books) (Second ed.). charleston, SC: Peninsula Press. p. 92. ISBN 1-57003-197-5. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ "History of the Huguenot Society".

- ^ "Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim".

- ^ "Brith Sholom Beth Israel".

- ^ "Charleston best-mannered city", CNN.com, January 17, 2004. Accessed May 9, 2007.

- ^ http://www.ibtimes.com/articles/346871/20120530/worst-dressed-cities-america.htm

- ^ "A 'portion mah of the People'," Harvard Magazine, January – February 2003. Retrieved June 11, 2007.

- ^ Joseph A. Opala [1]; The Gullah People and Their African Heritage by William S. Pollizer pp. 32–33

- ^ Joseph A. Opala

- ^ The Gullah People and Their African Heritage by William S. Pollitzer pp. 91–92

- ^ Mark Urban. Fusiliers.

- ^ "Profile for Charleston, South Carolina". ePodunk. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ^ Between August 1863 and March 1864, not a single blockade runner made it in or out of the harbor. Craig L. Symonds, The Civil War at Sea (2009) p. 57

- ^ "H. L. Hunley, Confederate Submarine," Department of the Navy – Naval Historical Center. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

- ^ "Century V City of Charleston Population 2010 Estimates" (PDF).

- ^ Maximum and minimum temperatures from Yahoo! Weather

- ^ Lane, F.W. The Elements Rage (David & Charles 1966), p. 49

- ^ "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- ^ "Climatological Normals of Charleston, South Carolina". Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ^ "List of Populations of Urbanized Areas". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-06-13. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.census.gov/prod/2006pubs/smadb/smadb-06.pdf

- ^ "Charleston County election results by precinct: 2006 general election".

- ^ "Investigation examining Charleston firefighters' handling of deadly blaze," KSLA News 12. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

- ^ "Fire department overview," City of Charleston Official Website. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ^ "2005 FBI Crime Reports". Charlestonsc.areaconnect.com. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ^ Michael Ledeen, "Hail to the Chief," National Review Online, August 18, 2005. Retrieved June 18, 2007.

- ^ "Charleston, South Carolina (SC) Detailed Profile – relocation, real estate, travel, jobs, hospitals, schools, crime, move, moving, houses news, sex offenders". City-data.com. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ^ http://os.cqpress.com/citycrime/CityCrime2008_Rank_Rev.pdf

- ^ "CQ Press: City Crime Rankings 2008". Os.cqpress.com. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ^ http://os.cqpress.com/citycrime/MetroCrime2008_Rank_Rev.pdf

- ^ North American Container Traffic (2009), Port Ranking by TEUs as reported by the American Association of Port Authorities

- ^ http://www.americanstyle.com/ME2/dirmod.asp?sid=&type=gen&mod=Core+Pages&gid=D4BC7638393C45F5B69956570EB94649

- ^ Zip Code boundaries provided to this site by United States Postal Service.

- ^ charlestoncity.info

- ^ http://zip4.usps.com/zip4/zcl_3_results.jsp?zip5=29406&submit=Find+ZIP+Code&pagenumber=0

- ^ http://www.ridetricountylink.com/index.html

- ^ Charleston ranks #1 in Customer Service

- ^ "North Charleston Intermodal Station Gains Funding". Great American Stations (Amtrak). Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ http://www.charlestonharbortours.com/article.cfm?EditorialID=27&CategoryID=0

- ^ "Huguenot Links". The Huguenot Society of America. Retrieved 2008-09-12. [dead link]

- ^ a b http://www.charlestonspoleto.org/charleston-spoleto-festivals.html

- ^ http://www.travelandleisure.com/americas-favorite-cities/2010/category/culture/theater-performance-art

- ^ http://www.footlightplayers.net

- ^ http://www.charlestonmysteries.com

- ^ Jinkins, Shirley (February 23, 1997). "Charleston S.C. has had a long and turbulent history, but a remarkable number of its buildings have survived". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ Richard Marcus. Book Review: Werewolf Smackdown by Mario Acevedo. Seattle PI. Posted: March 23, 2010

- ^ Charles Towne Landing

- ^ "Charleston drops in TV market pecking order".

- ^ "Television station listings in Charleston, South Carolina – Total station FCC filings found".

- ^ Charleston-Spoleto Sister City Web Site

- ^ Cultural Heritage Programme – The Barbados Carolina Connection, Barbados Ministry of Tourism

- ^ International Partnership Tells Story of Carolina–Barbados Connection, DiscoverSouthCarolina.com

- ^ Barbados: South Carolina's Mother Colony, SCIway.net

Further reading

General

- Borick, Carl P. A Gallant Defense: The Siege of Charleston, 1780. U. of South Carolina Press, 2003. 332 pp.

- Bull, Kinloch, Jr. The Oligarchs in Colonial and Revolutionary Charleston: Lieutenant Governor William Bull II and His Family. U. of South Carolina Press, 1991. 415 pp.

- Clarke, Peter. A Free Church in a Free Society. The Ecclesiology of John England, Bishop of Charleston, 1820–1842, a Nineteenth Century Missionary Bishop in the Southern United States. Charleston, South Carolina: Bagpipe, 1982. 561 pp.

- Coker, P. C., III. Charleston's Maritime Heritage, 1670–1865: An Illustrated History. Charleston, South Carolina: Coker-Craft, 1987. 314 pp.

- Doyle, Don H. New Men, New Cities, New South: Atlanta, Nashville, Charleston, Mobile, 1860–1910. U. of North Carolina Press, 1990. 369 pp.

- Fraser, Walter J., Jr. Charleston! Charleston! The History of a Southern City. U. of South Carolina, 1990. 542 pp. the standard scholarly history

- Gillespie, Joanna Bowen. The Life and Times of Martha Laurens Ramsay, 1759–1811. U. of South Carolina Press, 2001. 315 pp.

- Hagy, James William. This Happy Land: The Jews of Colonial and Antebellum Charleston. U. of Alabama Press, 1993. 450 pp.

- Jaher, Frederic Cople. The Urban Establishment: Upper Strata in Boston, New York, Charleston, Chicago, and Los Angeles. U. of Illinois Press, 1982. 777 pp.

- McInnis, Maurie D. The Politics of Taste in Antebellum Charleston. U. of North Carolina Press, 2005. 395 pp.

- Pease, William H. and Pease, Jane H. The Web of Progress: Private Values and Public Styles in Boston and Charleston, 1828–1843. Oxford U. Press, 1985. 352 pp.

- Pease, Jane H. and Pease, William H. A Family of Women: The Carolina Petigrus in Peace and War. U. of North Carolina Press, 1999. 328 pp.

- Pease, Jane H. and Pease, William H. Ladies, Women, and Wenches: Choice and Constraint in Antebellum Charleston and Boston. U. of North Carolina Press, 1990. 218 pp.

- Phelps, W. Chris. The Bombardment of Charleston, 1863–1865. Gretna, La.: Pelican, 2002. 175 pp.

- Rosen, Robert N. Confederate Charleston: An Illustrated History of the City and the People during the Civil War. U. of South Carolina Press, 1994. 181 pp.

- Rosen, Robert. A Short History of Charleston. University of South Carolina Press, (1997). ISBN 1-57003-197-5, scholarly survey

- Spence, E. Lee. Spence's Guide to South Carolina: diving, 639 shipwrecks (1520–1813), saltwater sport fishing, recreational shrimping, crabbing, oystering, clamming, saltwater aquarium, 136 campgrounds, 281 boat landings (Nelson Southern Printing, Sullivan's Island, South Carolina: Spence, ©1976) OCLC: 2846435

- Spence, E. Lee. Treasures of the Confederate Coast: the "real Rhett Butler" & Other Revelations (Narwhal Press, Charleston/Miami, ©1995)[ISBN 1-886391-01-7] [ISBN 1-886391-00-9], OCLC: 32431590

Art, architecture, literature, science

- Coles, John R.; Tiedj, Mark C. (June 4, 2009). Movie Theaters of Charleston. p. 97. ISBN 1-4414-9355-7.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - Cothran, James R. Gardens of Historic Charleston. U. of South Carolina Press, 1995. 177 pp.

- Gadsden Cultural Center; McMurphy, Make; Williams, Sullivan (4 October 2004). Sullivan's Island/Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7385-1678-3.

- Greene, Harlan. Mr. Skylark: John Bennett and the Charleston Renaissance. U. of Georgia Press, 2001. 372 pp.

- Hudgins; Carter L., ed (1994). The Vernacular Architecture of Charleston and the Lowcountry, 1670 – 1990. Charleston, South Carolina: Historic Charleston Foundation.

{{cite book}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - Hutchisson, James M. and Greene, Harlan, ed. Renaissance in Charleston: Art and Life in the Carolina Low Country, 1900–1940. U. of Georgia Press, 2003. 259 pp.

- Hutchisson, James M. DuBose Heyward: A Charleston Gentleman and the World of Porgy and Bess. U. Press of Mississippi, 2000. 225 pp.

- Jacoby, Mary Moore, ed (1994). The Churches of Charleston and the Lowcountry. Columbia South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-888-3.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help);|format=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) ISBN 978-0-87249-888-4. - McNeil, Jim. Charleston's Navy Yard: A Picture History. Charleston, South Carolina: Coker Craft, 1985. 217 pp.

- Moore, Margaret H (1997). Complete Charleston: A Guide to the Architecture, History, and Gardens of Charleston. Charleston, South Carolina: TM Photography. ISBN 0-9660144-0-5.

- O'Brien, Michael and Moltke-Hansen, David, ed. Intellectual Life in Antebellum Charleston. U. of Tennessee Press, 1986. 468 pp.

- Poston, Jonathan H. The Buildings of Charleston: A Guide to the City's Architecture. U. of South Carolina Press, 1997. 717 pp.

- Severens, Kenneth (1988). Charleston Antebellum Architecture and Civic Destiny. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. p. 315. ISBN 0-87049-555-0.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) ISBN 978-0-87049-555-7 - Smith, Alice R. Huger; Smith, D.E. Huger (1917). Dwelling Houses of Charleston, South Carolina. New York: Diadem Books.

- Stephens, Lester D. Science, Race, and Religion in the American South: John Bachman and the Charleston Circle of Naturalists, 1815–1895. U. of North Carolina Press, 2000. 338 pp.

- Stockton, Robert; et al. (1985). Information for Guides of Historic Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston, South Carolina: City of Charleston Tourism Commission.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first1=(help) - Waddell, Gene (2003). Charleston Architecture, 1670–1860. Charleston: Wyrick & Company. p. 992. ISBN 978-0-941711-68-5.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|volumes=ignored (help) ISBN 0-941711-68-4 - Weyeneth, Robert R. (2000). Historic Preservation for a Living City: Historic Charleston Foundation, 1947–1997. University of South Carolina Press. p. 256. ISBN 1-57003-353-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) ISBN 978-1-57003-353-7. - Yuhl, Stephanie E. A Golden Haze of Memory: The Making of Historic Charleston. U. of North Carolina Press, 2005. 285 pp.

- Zola, Gary Phillip. Isaac Harby of Charleston, 1788–1828: Jewish Reformer and Intellectual. U. of Alabama Press, 1994. 284 pp.

- Susan Harbage Page and Juan Logan. "Prop Master at Charleston's Gibbes Museum of Art", Southern Spaces, 21 September 2009.

Race

- Bellows, Barbara L. Benevolence among Slaveholders: Assisting the Poor in Charleston, 1670–1860. Louisiana State U. Press, 1993. 217 pp.

- Drago, Edmund L. Initiative, Paternalism, and Race Relations: Charleston's Avery Normal Institute. U. of Georgia Press, 1990. 402 pp.

- Egerton, Douglas R. He Shall Go Out Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey. Madison House, 1999. 248 pp. online review

- Greene, Harlan; Hutchins, Harry S., Jr.; and Hutchins, Brian E. Slave Badges and the Slave-Hire System in Charleston, South Carolina, 1783–1865. McFarland, 2004. 194 pp.

- Jenkins, Wilbert L. Seizing the New Day: African Americans in Post-Civil War Charleston. Indiana U. Press, 1998. 256 pp.

- Johnson, Michael P. and Roark, James L. No Chariot Let Down: Charleston's Free People of Color on the Eve of the Civil War. U. of North Carolina Press, 1984. 174 pp.

- Kennedy, Cynthia M. Braided Relations, Entwined Lives: The Women of Charleston's Urban Slave Society. Indiana U. Press, 2005. 311 pp.

- Powers, Bernard E., Jr. Black Charlestonians: A Social History, 1822–1885. U. of Arkansas Press, 1994. 377 pp.

External links

- Populated places established in 1670

- Populated places in Berkeley County, South Carolina

- Populated places in Charleston County, South Carolina

- Charleston, South Carolina

- Cities in South Carolina

- Former United States state capitals

- Port settlements in the United States

- United States colonial and territorial capitals

- County seats in South Carolina

- Regions of South Carolina

- Charleston–North Charleston–Summerville metropolitan area