Spanish missions in California: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

Lordkinbote (talk | contribs) →Missions in present–day California (U.S.): Asistencias in geographical order, north to south |

Lordkinbote (talk | contribs) m →Site selection and layout: add ref |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

{{main|Architecture of the California missions}} |

{{main|Architecture of the California missions}} |

||

In addition to the ''presidio'' (royal fort) and ''pueblo'' (town), the ''misión'' was one of the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown to extend its borders and consolidate its [[colonial]] territories. ''Asistencias'' ("satellite" or "sub" missions, sometimes referred to as "contributing chapels") were small-scale missions that regularly conducted Divine service on days of obligation but lacked a resident priest. Since 1493, the Kingdom of [[Spain]] had maintained a number of missions throughout ''Nueva España'' ([[New Spain]], consisting of [[Mexico]] and portions of what today are the [[Southwestern United States|Southwestern]] [[United States]]) in order to facilitate colonization of these lands. In this context, the term "California" is used to refer to the territory that comprises [[Alta California]] (chiefly the current U.S. state of [[California]]) and the Mexican states of [[Baja California]] and [[Baja California Sur]]. It was not until the threat of invasion by [[Imperial Russia|Tsarist Russia]], in 1765, however, that the King felt such installations were necessary in Upper ("Alta") California. Between 1774 and 1791, the Crown sent forth a number of expeditions to explore the [[Pacific Northwest]], but, by 1819, chose to limit its "reach" to [[Northern California]] due to the costs involved in sustaining such remote outposts. |

In addition to the ''presidio'' (royal fort) and ''pueblo'' (town), the ''misión'' was one of the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown to extend its borders and consolidate its [[colonial]] territories. ''Asistencias'' ("satellite" or "sub" missions, sometimes referred to as "contributing chapels") were small-scale missions that regularly conducted Divine service on days of obligation but lacked a resident priest.<ref>Harley</ref> Since 1493, the Kingdom of [[Spain]] had maintained a number of missions throughout ''Nueva España'' ([[New Spain]], consisting of [[Mexico]] and portions of what today are the [[Southwestern United States|Southwestern]] [[United States]]) in order to facilitate colonization of these lands. In this context, the term "California" is used to refer to the territory that comprises [[Alta California]] (chiefly the current U.S. state of [[California]]) and the Mexican states of [[Baja California]] and [[Baja California Sur]]. It was not until the threat of invasion by [[Imperial Russia|Tsarist Russia]], in 1765, however, that the King felt such installations were necessary in Upper ("Alta") California. Between 1774 and 1791, the Crown sent forth a number of expeditions to explore the [[Pacific Northwest]], but, by 1819, chose to limit its "reach" to [[Northern California]] due to the costs involved in sustaining such remote outposts. |

||

Each [[frontier]] station was forced to be self-supporting, as existing means of supply were inadequate to maintain a colony of any size. California was literally months away from the nearest base in colonized Mexico, and the cargo [[ship]]s of the day were too small to carry more than a few months’ [[ration]]s in their holds. In order to sustain a mission, the ''padres'' required the help of [[colonist]]s or converted [[Native Americans in the United States|Native Americans]], called ''neophytes'', to cultivate [[agriculture|crops]] and tend [[livestock]] in the volume needed to support a fair-sized establishment. The scarcity of imported materials, together with a lack of skilled laborers, compelled the Fathers to employ simple building materials and methods in the construction of mission structures. |

Each [[frontier]] station was forced to be self-supporting, as existing means of supply were inadequate to maintain a colony of any size. California was literally months away from the nearest base in colonized Mexico, and the cargo [[ship]]s of the day were too small to carry more than a few months’ [[ration]]s in their holds. In order to sustain a mission, the ''padres'' required the help of [[colonist]]s or converted [[Native Americans in the United States|Native Americans]], called ''neophytes'', to cultivate [[agriculture|crops]] and tend [[livestock]] in the volume needed to support a fair-sized establishment. The scarcity of imported materials, together with a lack of skilled laborers, compelled the Fathers to employ simple building materials and methods in the construction of mission structures. |

||

Revision as of 18:55, 21 November 2006

Part of a series on |

| Spanish missions in the Americas of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Missions in North America |

| Missions in South America |

| Related topics |

|

|

The Spanish Missions in California (more simply referred to as the "California Missions") comprise a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholic on the Franciscan Order between 1769 and 1823 to spread the Christian doctrine among the local Native Americans. The missions represented the first major effort by Europeans to colonize the Pacific Coast region, and gave Spain a valuable toehold in the frontier land. The settlers introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, and industry into the California region; however, the Spanish occupation of California also brought with it serious, though unintended, negative consequences to the Native American populations the missionaries came in contact with. Today, the missions are among the state's oldest structures and the most-visited historic monuments.

History

As early as the voyages of Christopher Columbus, the Kingdom of Spain sought to establish missions to convert Pagans to Catholicism in Nueva España (New Spain, consisting of the Caribbean, of Mexico and portions of what today are the Southwestern United States), in order to facilitate colonization of these lands awarded to Spain by the Catholic Church. The modern region "California" refers to the Spanish territory formerly known as Alta California. It was not until (with the Vitus Bering expedition of 1741) that the territorial ambitions of Tsarist Russia towards North America became known, however, that the King felt such installations were necessary in Upper ("Alta") California. Between 1774 and 1791, the Spanish Crown sent forth a number of expeditions to explore the Pacific Northwest.

The Spanish mission system arose in part from the need to control Spain's ever-expanding holdings in the New World. Realizing that the colonies would require a literate population base that the mother country could not supply, the Spanish Crown (with the cooperation of the Church) established a network of missions with the goal of converting the natives to Christianity; the aim was to make converts and tax paying citizens of the indigenous peoples they conquered. In order to become Spanish citizens and productive inhabitants, the native Americans were required to learn Spanish language and vocational skills along with Christian teachings. In the words of clerical historian Maynard Geiger, "This was to be a cooperative effort, imperial in origin, protective in purpose, but primarily spiritual in execution." With the expulsion of the Jesuits from Baja California in 1768, Visitador General José de Gálvez engaged the Franciscan Order to take over the administration of the missions there. This plan, however, was changed within a few months after Gálvez received the following orders: "Occupy and fortify San Diego and Monterey for God and the King of Spain." It thereupon was decided to call upon the priests of the Dominican Order to take charge of the Baja California missions in order to allow the Franciscans to concentrate on founding new missions in Alta California. On July 14, 1769 Gálvez sent the expedition of Junípero Serra and Gaspar de Portolà to found a mission at San Diego and presidio at Monterey, respectively.[2] En route, Fathers Francisco Gómez and Juan Crespí came across a native settlement wherein two young girls were dying: one, a baby said to be "dying at its mother's breast," the other a small girl suffering of burns. On July 22, Father Gómez baptized the baby, giving her the name "Maria Magdalena," while Father Crespí baptized the older child, naming her "Margarita" (the expedition's soldiers referred to the girls as Los Cristianitos, or "The Little Christians"). These were the first recorded baptisms in Alta California.[3] Today, the site known as La Cristianita (located at 33°25′41.58″N 117°36′34.92″W / 33.4282167°N 117.6097000°W on Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton in San Diego County) is designated as California Historical Landmark #562. The group continued northward but missed Monterey Harbor and returned to San Diego on January 24, 1770. Near the end of 1771 the Portolà Expedition arrived at San Francisco Bay. Arguably "the worst epidemic of the Spanish Era in California" was known to be the measles epidemic of 1806, wherein one-quarter of the mission Indian population of the San Francisco Bay area died of the measles or related complications between March and May of that year.[4]

Each mission was to be turned over to a secular clergy and all the common mission lands distributed amongst the native population within ten years after its founding, a policy that was based upon Spain's experience with the more advanced tribes in Mexico, Central America, and Peru. In time, it became obvious to Father Serra and his associates that the Indian tribes on the northern frontier in Alta California would require a much longer period of acclimatization.[5] None of the California missions ever attained self-sufficiency, and required continued (albeit modest) financial support from mother Spain, out of what was often referred to as the "Pius Fund." Starting with the onset of the Mexican War of Independence in 1810, this support largely disappeared and the missions and their converts were left on their own. By 1819 Spain decided to limit its "reach" in the New World to Northern California due to the costs involved in sustaining these remote outposts; the northernmost settlement is Mission San Francisco Solano, founded in Sonoma in 1823. In November and December of 1818 several of the missions were attacked by Hipólito Bouchard, "California's only pirate." A French privateer sailing under the flag of Argentina, Pirate Buchar (as he was known to the locals) worked his way down the California coast, conducting raids on the installations at Monterey, Santa Barbara, and San Juan Capistrano, with limited success.[6] Upon hearing of the attacks, many mission priests (along with a few government officials) sought refuge at Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, the mission chain's most isolated outpost. Ironically, Mission Santa Cruz (though ultimately ignored by the marauders) was ignominiously sacked and vandalized by local residents who were entrusted with securing the church's valuables.[7]

As the Mexican republic matured, calls for the secularization ("disestablishment") of the missions increased. As a first step, José Maria de Echeandía (Mexican Governor of Alta California) issued a proclamation on July 25, 1826 stating that any natives who desired to leave the missions might do so, "...provided they had been Christians from childhood, or for fifteen years, were married, or at least not minors, and had some means of gaining a livelihood." Although Governor José Figueroa, who took office in 1833, initially attempted to keep the mission system intact, the Mexican Congress nevertheless passed An Act for the Secularization of the Missions of California (or "Prevenciónes de Emancipacion") on August 17 of that year.[8] The Act, which was ratified in 1834, also provided for the colonization of both Alta and Baja California, the expenses of this latter move to be borne by the proceeds gained from the sale of the mission property to private interests. Mission San Juan Capistrano was the very first to feel the effects of this legislation the following year. Nine other settlements quickly followed, with six more in 1835; San Buenaventura and San Francisco de Asís were among the last to succumb, in June and December of 1836, respectively.[9] The Franciscans soon thereafter abandoned most of the missions, taking with them most everything of value, after which the locals typically plundered the mission buildings for construction materials.

Pío de Jesus Pico IV, the last Mexican Governor of Alta California, found upon taking office that there were few funds available with which to carry on the affairs of the province. He prevailed upon the assembly to pass a decree authorizing the renting or the sale of all mission property, reserving only the church, a curate's house, and a building for a courthouse. The expenses of conducting the services of the church were to be provided from the proceeds, but there was no disposition made as to what should be done to secure the funds for that purpose. After secularization, Father Presidente Narciso Durán transferred the missions' headquarters to Santa Barbara, thereby making Mission Santa Barbara the repository of some 3,000 original documents that had been scattered through the California missions. The Mission archive is the oldest library in the State of California that still remains in the hands of its founders, the Franciscans (it is the only mission in which they have maintained an uninterrupted presence). Beginning with the writings of Hubert Howe Bancroft, the library has served as a center for historical study of the missions for more than a century.

By way of confiscation of the missions between 1834 and 1838 the Indians lost the protection of the mission system, along with their stock and other movable property; by the transfer of California to the United States, they were left without legal title to their land. As the result of a U.S. government investigation in 1873 a number of Indian reservations were assigned by executive proclamation in 1875. According to one estimate, the original population in and around the missions proper was approximately 80,000 at the time of the confiscation. It is estimated the "pre-colonization" native population in Alta California (which numbered around 300,000) had dwindled to approximately 100,000, by the early 1840s, due in large part to the natives' exposure to European diseases for which they lacked immunity and from the Franciscan practice of cloistering women in the convento and controlling sexuality during the child-bearing age; Baja California experienced a similar reduction in native population resulting from Spanish colonization efforts there. In recent years, much debate has arisen as to the actual treatment of the Indians during the Mission period, and many claim that the California Mission system is directly responsible for the decline of the native cultures. Evidence has now been brought to light that puts the Indians' experiences in a very different context.

Mission life

A total of 146 Friars Minor, all of whom were ordained as priests (and mostly Spaniards by birth) served in California between 1769–1845. 67 missionaries died at their posts (two as martyrs: Padres Luís Jayme and Andrés Quintana), while the remainder returned to Europe due to illness, or upon completion their ten-year service commitment.[11] As the rules of the Franciscan Order forbade friars to live alone, two missionaries were assigned to each settlement. To these the governor assigned a guard of five or six soldiers under the command of a corporal, who generally acted as steward of the mission's temporal affairs, subject to the fathers' direction.[12]

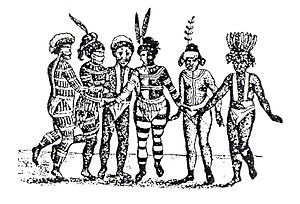

Life at the California missions varied slightly throughout the entire system. Once a "gentile" was baptized, he or she became a neophyte, or new believer. This happened only after a brief period during which the initiates were instructed in the most basic aspects of the Catholic faith. But, while many natives were lured to join the missions out of curiosity and sincere desire to participate and engage in trade, many found themselves trapped once they received the "sacrament" of baptism. To the padres, a baptized Indian was no longer free to move about the country, but had to labor and worship at the mission under the strict observance of the padres and overseers, who herded them to daily masses and labors. If an Indian did not report for their duties for a period of a few days, they were searched for, and if it was discovered that they left without permission, they were considered runaways. Young native women were required to reside in the convento (also known as a monjério, or "nunnery") under the supervision of a trusted Indian matron who bore the responsibility for their welfare and education. Women only left the convent after they had been "won" by an Indian suitor and were deemed ready for marriage. Following Spanish custom, courtship took place between a barred window. After the marriage ceremony the woman moved out of the mission compound and into one of the family huts.[13] These "nunneries" were considered a necessity by the padres, who felt the women needed to be protected from the men, both Indian and "de razón." The cramped and unsanitary conditions the girls lived in contributed to the fast spread of disease and population decline. So many died at times, that many of the Indian residents of the missions urged the padres to raid new villages to supply them with more women.

The daily routine began with sunrise Mass and morning prayers, followed by instruction of the natives in the teachings of the Roman Catholic faith. After a generous (by era standards) breakfast of atole (porridge), the able-bodied men and women were assigned their tasks for the day. The women were committed to dressmaking, knitting, weaving, embroidering, laundering, and cooking, while some of the stronger girls would grind flour or carry adobe bricks (weighing 55 lb, or 25 kg each) to the men engaged in building. The men were tasked with a variety of jobs, having learned from the missionaries how to plow, sow, irrigate, cultivate, reap, thresh, and glean. In addition, they were taught to build adobe houses, tan leather hides, shear sheep, weave rugs and clothing from wool, make ropes, soap, paint, and other useful duties. The work day was six hours, interrupted by dinner (lunch) around 11:00 a.m. and a two-hour siesta, and ended with evening prayers and the rosary, supper, and social activities. About 90 days out of each year were designated as religious or civil holidays, free from manual labor. The labor organization of the missions resembled a slave plantation in many respects. Foreigners who visited the missions remarked at how the padres' control over the Indians appeared excessive, but necessary given the white mens' isolation and numeric disadvantage. Indians were not paid wages as they were not considered free laborers and, as a result, the missions were able to extract surplus value for the goods produced by the Mission Indians to the detriment of the other Spanish and Mexican settlers of the time who could not compete economically with the advantage of the mission system.

Mission industries

The goal of the missions was, above all, to become self-sufficient in relatively short order. Farming, therefore, was the most important industry of any mission. Barley, maize, and wheat were among the most common crops grown. Even today, California is well-known for the abundance and many varieties of fruit trees that are cultivated throughout the state. The only fruits indigenous to the region, however, consisted of wild berries or grew on small bushes. Spanish missionaries brought fruit seeds over from Europe, many of which had been introduced to the Old World from Asia following earlier expeditions to the continent; orange, grape, apple, peach, pear, and fig seeds were among the most prolific of the imports. Mission San Gabriel Arcángel would unknowingly witness the origin of the California citrus industry with the planting of the region’s first significant orchard in 1804, though the commercial potential of citrus would not be realized until 1841.[15] Olives (first cultivated at Mission San Diego de Alcalá) were grown, cured, and pressed under large stone wheels to extract their oil, both for use at the mission and to trade for other goods. Grapes were also grown and fermented into wine for sacramental use and again, for trading. The specific variety, called the Criolla or "Mission grape," was first planted at Mission San Juan Capistrano in 1779; in 1783, the first wine produced in Alta California emerged from the mission's winery. Cereal grains were dried and ground by stone into flour.

It was also the missions' responsibility to provide the Spanish forts, or "presidios", with the necessary foodstuffs, and manufactured goods to sustain operations. It was a constant point of contention between missionaries and the soldiers as to how many "fanegas" of barley, or how many shirts or blankets the mission had to provide the garrisons on any given year. At times these requirements were hard to meet, especially during years of drought, or when the much anticipated shipments from the port of San Blas failed to arrive.

Livestock was raised, not only for the purpose of obtaining meat, but also for wool, leather, and tallow, and for cultivating the land. At the height of their prosperity, the missions collectively owned:

- 232,000 head of cattle;

- 268,000 sheep;

- 34,000 horses;

- 3,500 mules or burros;

- 8,300 goats; and

- 3,400 swine.

All of these animals were originally brought up from Mexico. A great many Indians were required to guard the herds and flocks, which created the need for "...a class of horsemen scarcely surpassed anywhere." [16] These animals multiplied beyond the settler's expectations, ofen overruning pastures and extending well-beyond the domains of the missions. The giant herds or horses and cows took well to the climate and the extensive pastures of the Coastal California region, but at a heavy price for the Native inhabitants. The uncontrolled spread of these new species quickly exhausted the grasslands and hillsides the Indinas depended on for their seed harvests. This problem was also recognized by the Spaniards themselves, who at times sent out extermination parties to kill thousands of excess livestock, when the populations grew beyond their control.

Mission kitchens and bakeries prepared and served thousands of meals each day. Candles, soap, grease, and ointments were all made from tallow (rendered animal fat) in large vats located just outside the west wing. Also situated in this general area were vats for dyeing wool and tanning leather, and primitive looms for weavings. Large bodegas (warehouses) provided long-term storage for preserved foodstuffs and other treated materials.

Each mission had to fabricate virtually all of its construction materials from local materials. Workers in the carpintería (carpentry shop) used crude methods to shape beams, lintels, and other structural elements; more skilled artisans carved doors, furniture, and wooden implements. For certain applications bricks (ladrillos) were fired in ovens (kilns) to strengthen them and make them more resistant to the elements; when tejas (roof tiles) eventually replaced the conventional jacal roofing (densely-packed reeds) they were placed in the kilns to harden them as well. Glazed ceramic pots, dishes, and canisters were also made in mission kilns. Prior to the arrival of the missions, the native peoples knew only how to utilize bone, seashells, stone, and wood for building, tool making, weapons, and so forth. The foundry at Mission San Juan Capistrano was the first to introduce the Indians to the Iron Age. The blacksmith used the mission’s Catalan furnaces (California’s first) to smelt and fashion iron into everything from basic tools and hardware (such as nails) to crosses, gates, hinges, even cannon for mission defense. Iron was one commodity in particular that the mission relied solely on trade to acquire, as the missionaries had neither the know-how nor the technology to mine and process metal ores.

No study of the missions would be complete without mention of their extensive water supply systems. Stone zanjas (aqueducts), sometimes spanning miles, brought fresh water from a nearby river or spring to the mission site. Baked clay pipes, joined together with lime mortar or bitumen, deposited the water into large cisterns and gravity-fed fountains, and emptied into waterways where the force of the water was used to turn grinding wheels and other simple machinery, or dispensed for use in cleaning. Water used for drinking and cooking was allowed to trickle through alternate layers of sand and charcoal to remove the impurities.

Site selection and layout

In addition to the presidio (royal fort) and pueblo (town), the misión was one of the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown to extend its borders and consolidate its colonial territories. Asistencias ("satellite" or "sub" missions, sometimes referred to as "contributing chapels") were small-scale missions that regularly conducted Divine service on days of obligation but lacked a resident priest.[17] Since 1493, the Kingdom of Spain had maintained a number of missions throughout Nueva España (New Spain, consisting of Mexico and portions of what today are the Southwestern United States) in order to facilitate colonization of these lands. In this context, the term "California" is used to refer to the territory that comprises Alta California (chiefly the current U.S. state of California) and the Mexican states of Baja California and Baja California Sur. It was not until the threat of invasion by Tsarist Russia, in 1765, however, that the King felt such installations were necessary in Upper ("Alta") California. Between 1774 and 1791, the Crown sent forth a number of expeditions to explore the Pacific Northwest, but, by 1819, chose to limit its "reach" to Northern California due to the costs involved in sustaining such remote outposts.

Each frontier station was forced to be self-supporting, as existing means of supply were inadequate to maintain a colony of any size. California was literally months away from the nearest base in colonized Mexico, and the cargo ships of the day were too small to carry more than a few months’ rations in their holds. In order to sustain a mission, the padres required the help of colonists or converted Native Americans, called neophytes, to cultivate crops and tend livestock in the volume needed to support a fair-sized establishment. The scarcity of imported materials, together with a lack of skilled laborers, compelled the Fathers to employ simple building materials and methods in the construction of mission structures.

Although the missions were considered temporary ventures by the Spanish hierarchy, the development of an individual settlement was not simply a matter of "priestly whim." The founding of a mission followed longstanding rules and procedures; the paperwork involved required months, sometimes years of correspondence, and demanded the attention of virtually every level of the bureaucracy. Once empowered to erect a mission in a given area, the men assigned to it chose a specific site that featured a good water supply, plenty of wood for fires and building material, and ample fields for grazing herds and raising crops. The padres blessed the site, and with the aid of their military escort fashioned temporary shelters out of tree limbs or driven stakes, roofed with thatch or reeds (cañas). It was these simple huts that would ultimately give way to the stone and adobe buildings which exist to this day.

The first priority when beginning a settlement was the location and construction of the church (iglesia). The majority of mission sanctuaries were oriented on a roughly east-west axis to take the best advantage of the sun's position for interior illumination; the exact alignment depended on the geographic features of the particular site. Once the spot for the church was selected, its position would be marked and the remainder of the mission complex would be laid out. The workshops, kitchens, living quarters, storerooms, and other ancillary chambers were usually grouped in the form of a quadrangle, inside which religious celebrations and other festive events often took place. The cuadrángulo was rarely a perfect square because the Fathers had no surveying instruments at their disposal and simply measured off all dimensions by foot.

Missions in present–day California (U.S.)

The 21 Alta California missions were established along the northernmost section of California's El Camino Real (Spanish for "The Royal Highway," though often referred to as "The King's Highway"), christened in honor of King Charles III), much of which is now U.S. Route 101 and several Mission Streets. The mission planning was begun in 1767 under the leadership of Fray Junípero Serra, O.F.M. (who, in 1767, along with his fellow priests, had taken control over a group of missions in Baja California previously administered by the Jesuits). In September, 1821 Father Mariano Payeras, "Comisario Prefecto" of the California Missions, visited Cañada de Santa Ysabel as part of a plan to establish an entire chain of inland missions, with the Santa Ysabel Asistencia as the "mother" mission. The plan never came to fruition, however. Work on the mission chain was concluded in 1823, even though Serra had died in 1784. Father Fermín Francisco de Lasuén took up Serra's work and established nine more mission sites, from 1786 through 1798; others established the last three compounds, along with seven asistencia.[18] Two short-lived settlements, Mission Puerto de Purísima Concepción and Mission San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer, though located on the California side of the Colorado River, were founded under the authority of the Arizona mission hierarchy and are therefore not included herein.

The missions are collectively the best-known historic element of the coastal regions of California. Seven of the twenty-one missions are designated National Historic Landmarks, fourteen are listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and all are designated as California Historical Landmarks for their historic, architectural, and archaeological significance. In 1875 American illustrator Henry Ford Chapman began visiting each of the twenty-one mission sites, where he created a historically-important portfolio of watercolors, oils, and etchings. His depictions of the missions were (in part) responsible for the revival of interest in the state's Spanish heritage, and indirectly for the restoration of the missions. The popularity of the missions also stems largely from Helen Hunt Jackson's 1884 novel Ramona and the subsequent efforts of Charles Fletcher Lummis, William Randolph Hearst, and other members of the Landmarks Club of Los Angeles to restore the missions in the early 20th century. In 1911 author John Steven McGroarty penned The Mission Play, a three-hour pageant describing the California missions from their founding in 1769 through secularization in 1834, and ending with their "final ruin" in 1847. The missions have earned a prominent place in California's historic consciousness, and a steady stream of tourists from all over the world visit them.

Today, the missions exist in varying degrees of architectural integrity and structural soundness. The most common extant features at the mission grounds include the church building and an ancillary convento (convent) wing. In some cases (in San Rafael, Santa Cruz, and Soledad, for example), the current buildings are replicas constructed on or near the original site. Other mission compounds remain relatively intact and true to their original, Mission Era construction. A notable example of an intact complex is the now-threatened Mission San Miguel Arcángel: its chapel retains the original interior murals created by Salinan Indians under the direction of Esteban Munras, a Spanish artist. This structure was closed to the public, in 2003, due to severe damage from the San Simeon Earthquake. Many missions have preserved (or in some cases reconstructed) historic features in addition to chapel buildings. Mission San Luis Rey de Francia in Oceanside has a well-preserved lavanderia (washing area) with Indian-made gargoyles for water spouts and clear depressions where native women washed clothes on the bricks. Mission San Antonio de Padua near Jolon has more than 100 acres (0.4 km²) of archaeological and built features, including sawpits, reservoirs, and the foundations of the soldiers' barracks, a threshing room, and married Indian convert housing.

In order to facilitate overland travel, the mission settlements were situated approximately 30 miles (48 kilometers) apart, so that they were separated by one day's long ride on horseback (or three days on foot) along the 600-mile (966-kilometer) long "California Mission Trail." Father Lasuén is credited for having brought the concept to life in 1798 when he successfully argued that filling in the "spaces" along El Camino Real with additional outposts would provide much-needed rest stops, where travelers could take lodging in relative safety and comfort.[19] Heavy freight movement was practical only via water. Tradition has it that the padres sprinkled mustard seeds along the trail in order to mark it with bright yellow flowers.

In geographical order, north to south

- Mission San Francisco Solano, in Sonoma

- Mission San Rafael Arcángel, in San Rafael

- Mission San Francisco de Asís (Mission Dolores), in San Francisco

- Mission San José, in Fremont

- Mission Santa Clara de Asís, in Santa Clara

- Mission Santa Cruz, in Santa Cruz

- Mission San Juan Bautista, in San Juan Bautista

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, south of Carmel

- Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, south of Soledad

- Mission San Antonio de Padua, northwest of Jolon

- Mission San Miguel Arcángel, north of Paso Robles

- Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, in San Luis Obispo

- Mission La Purísima Concepción, northeast of Lompoc

- Mission Santa Inés, in Solvang

- Mission Santa Barbara, in Santa Barbara

- Mission San Buenaventura, in Ventura

- Mission San Fernando Rey de España, in Mission Hills (Los Angeles)

- Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, in San Gabriel

- Mission San Juan Capistrano, in San Juan Capistrano

- Mission San Luís Rey de Francia, in Oceanside

- Mission San Diego de Alcalá, in San Diego

In chronological order

Franciscan Establishments (1769–1823)

- Mission San Diego de Alcalá founded in 1769

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo founded in 1770

- Mission San Antonio de Padua founded in 1771

- Mission San Gabriel Arcángel founded in 1771

- Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa founded in 1772

- Mission San Francisco de Asís (Mission Dolores) founded in 1776

- Mission San Juan Capistrano founded in 1776

- Mission Santa Clara de Asís founded in 1777

- Mission San Buenaventura founded in 1782

- Mission Santa Barbara founded in 1786

- Mission La Purísima Concepción founded in 1787

- Mission Santa Cruz founded in 1791

- Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad founded in 1791

- Mission San José founded in 1797

- Mission San Juan Bautista founded in 1797

- Mission San Miguel Arcángel founded in 1797

- Mission San Fernando Rey de España founded in 1797

- Mission San Luis Rey de Francia founded in 1798

- Mission Santa Inés founded in 1804

- Mission San Antonio de Pala (Pala Asistencia) founded in 1816

- Mission San Rafael Arcángel founded in 1817 — originally planned as an asistencia to Mission San Francisco de Asís

- Mission San Francisco Solano founded in 1823 — originally planned as an asistencia to Mission San Rafael Arcángel

Asistencias in geographical order, north to south

- San Pedro y San Pablo Asistencia, founded in 1786 in Pacifica

- Santa Margarita Asistencia, founded in 1787 in Santa Margarita

- San Bernardino Asistencia, founded in 1819 in Redlands

- Mission Nuestra Señora Reina de los Angeles, founded in 1781 in Los Angeles

- Las Flores Asistencia (Las Flores Estancia), founded in 1823 in Camp Pendleton

- Santa Ysabel Asistencia, founded in 1818 in Santa Ysabel

- Mission San Antonio de Pala (Pala Asistencia), founded in 1816 in eastern San Diego County

Headquarters of the Alta California Mission System

- Mission San Diego de Alcalá (1769–1771)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (1771–1815)

- Mission La Purísima Concepción* (1815–1819)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (1819–1824)

- Mission San José* (1824–1827)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (1827–1830)

- Mission San José* (1830–1833)

- Mission Santa Barbara (1833–1846)

* Fathers Payeras and Durán remained at their resident missions during their terms as "Father-Presidente," therefore those settlements became the de facto headquarters (until 1833, when all mission records were permanently relocated to Santa Barbara).[20]

Father-Presidents of the Alta California Mission System

- Father Junípero Serra (1769–1784)

- Father Francisco Palóu (acting) (1784–1785)

- Father Fermín Francisco de Lasuén (1785–1803)

- Father Pedro Estévan Tápis (1803–1812)

- Father José Francisco de Paula Señan (1812–1815)

- Father Mariano Payeras (1815–1819)

- Father José Francisco de Paula Señan (1820–1823)

- Father Vicente Francisco de Sarría (1823–1824)

- Father Narciso Durán (1824–1827)

- Father José Bernardo Sánchez (1827–1830)

- Father Narciso Durán (1830–1838)

- Father José Joaquin Jimeno (1838–1844)

- Father Narciso Durán (1844–1846)

Military Districts

Four presidios, strategically placed along the California coast, served to protect the missions and other Spanish settlements in Upper California. Each of these posts functioned as a base of military operations for a specific region, organized as follows:

- El Presidio Real de San Diego founded on July 16, 1769 — responsible for the defense of all installations within the First Military District;[21]

- El Presidio Real de Santa Bárbara founded on April 12, 1782 — responsible for the defense of all installations within the Second Military District;[22]

- El Presidio Real de San Carlos de Monterey (El Castillo) founded on June 3, 1770 — responsible for the defense of all installations within the Third Military District;[23]

- El Presidio Real de San Francisco founded on December 17, 1776 — responsible for the defense of all installations within the Fourth Military District.[24]

El Presidio de Sonoma, or Sonoma Barracks (a collection of guardhouses, storerooms, living quarters, and an observation tower) was established in 1836 by Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (the "Commandante-General of the Northern Frontier of Alta California") as a part of Mexico's strategy to halt Russian incursions into the region.[25] The Sonoma Presidio became the new headquarters of the Mexican Army in California, while the remaining presidios were essentially abandoned and, in time, fell into ruins.

Controversy

There is controversy over the California Department of Education's treatment of the missions in the Department's elementary curriculum. A number of parents have complained about the so-called "mission projects" many children are assigned in the fourth grade; in the tradition of historical revisionism, it has been alleged that the curriculum "waters down" the harsh treatment of Native Americans. For instance, the role of historical figures, such as Father Serra, can be interpreted as either one of cultural imperialism or as a noble cause, depending upon the context given.

Notes

- ^ Kelsey, p. 18

- ^ Yenne, p. 10

- ^ Leffingwell, p. 25

- ^ Milliken, pp. 172-173, 193

- ^ Engelhardt, pp. 3-18

- ^ Jones, p. 170

- ^ Young, p. 102

- ^ Yenne, p. 19

- ^ Yenne, pp. 83, 93

- ^ Kelsey, p. 4

- ^ Leffingwell, pp. 19, 132

- ^ Engelhardt, pp. 3-18

- ^ Newcomb, p. viii

- ^ Kelsey, p. 5

- ^ Thompson, p. 341

- ^ Engelhardt, pp. 3-18

- ^ Harley

- ^ Young, p. 17

- ^ Yenne, p. 132

- ^ Yenne, p. 186

- ^ Leffingwell, p. 22

- ^ Leffingwell, p. 68

- ^ Leffingwell, p. 119

- ^ Leffingwell, p. 154

- ^ Leffingwell, p. 170

References

- Engelhardt, Zephyrin, O.F.M. (1908). Missions and Missionaries, Volume One. The James H. Barry Co., San Francisco, CA.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Geiger, Maynard J., O.F.M., Ph.D. (1969). Franciscan Missionaries in Hispanic California, 1769-1848: A Biographical Dictionary. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jones, Roger W. (1997). California from the Conquistadores to the Legends of Laguna. Rockledge Enterprises, Laguna Hills, CA.

- Kelsey, H. (1993). Mission San Juan Capistrano: A Pocket History. Interdisciplinary Research, Inc., Altadena, CA.

- Milliken, Randall (1995). A Time of Little Choice: The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area 1769-1910. Ballena Press, Menlo Park, CA. ISBN 0-87919-132-5.

- Newcomb, Rexford (1973). The Franciscan Mission Architecture of Alta California. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, NY. ISBN 0-486-21740-X.

- Thompson, Anthony W., Robert J. Church, and Bruce H. Jones (2000). Pacific Fruit Express. Signature Press, Wilton, CA. ISBN 1-930013-03-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Yenne, Bill (2004). The Missions of California. Advantage Publshers Group, San Diego, CA. ISBN 1-59223-319-8.

- Young, S., and Levick, M. (1988). The Missions of California. Chronicle Books LLC, San Francisco, CA. ISBN 0-8118-1938-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Baer, Kurt (1958). Architecture of the California Missions. University of California Press, Los Angeles, CA.

- Carillo, J. M., O.F.M. (1967). The Story of Mission San Antonio de Padua. Paisano Press, Inc., Balboa Island, CA.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Camphouse, M. (1974). Guidebook to the Missions of California. Anderson, Ritchie & Simon, Los Angeles, CA. ISBN 0-378-03792-7.

- Crump, S. (1975). California's Spanish Missions: Their Yesterdays and Todays. Trans-Anglo Books, Del Mar, CA. ISBN 0-87046-028-5.

- Drager, K., and Fracchia, C. (1997). The Golden Dream: California from Gold Rush to Statehood. Graphic Arts Center Publishing Company, Portland, OR. ISBN 1-55868-312-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Johnson, P., ed. (1964). The California Missions. Lane Book Company, Menlo Park, CA.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Leffingwell, Randy (2005). California Missions and Presidios: The History & Beauty of the Spanish Missions. Voyageur Press, Inc., Stillwater, MN. ISBN 0-89658-492-5.

- Moorhead, Max L. (1991). The Presidio: Bastion Of The Spanish Borderlands. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK. ISBN 0-8061-2317-6.

- Rawls, J. and Bean, W. (1997). California: An Interpretive History. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. ISBN 0-07-052411-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Robinson, W. (1953). Panorama: A Picture History of Southern California. Anderson, Ritchie & Simon, Los Angeles, CA.

- Weitze, Karen J. (1984). California's Mission Revival. Hennessy & Ingalls, Inc., Los Angeles, CA. ISBN 0-912158-89-1.

- Wright, Ralph B., Ed. (1950). California's Missions. Hubert A. and Martha H. Lowman, Arroyo Grande, CA.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

See also

- California 4th Grade Mission Project

- History of California to 1899

- History of Christian Missions

- Jesuit Asia missions

- Jesuit Reductions

- Missionary

- Reductions

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

External links

- www.ca-missions.org — The official website of the California Mission Studies Association, a good source of accurate, peer-reviewed information on Mission Era history with an extensive links page.

- www.missionsofcalifornia.org — The official website of the California Missions Foundation (a secular, nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the California missions and their associated art and artifacts for the public benefit) includes contact information for each mission, directions, and a brief accounting of their preservation needs.

- Almanac: California Missions

- Animated Map of Mission Formation in Alta California

- California Highways - Trails and Roads: El Camino Real

- California Historical Society official website

- Californias-Missions.org: A Resource Website for Students, Parents, and Teachers

- California Missions

- California Missions article at The Catholic Encyclopedia

- The California Missions

- California Missions: A Virtual Tour

- Early California History: The Missions

- Mission Tour Home

- The Old Franciscan Missions of California eText at Project Gutenberg

- The San Diego Founders Trail official website

- National Register of Historic Places official website

- Junipero Serra, the Vatican, & Enslavement Theology offers a critical perspective on the missions' impact on California's Indians