Berlin Blockade

The Berlin Blockade (June 21, 1948 to May 11, 1949) became one of the first major crises of the new Cold War, when the Soviet Union blocked railroad and street access to West Berlin. The crisis abated after the Soviet Union did not act to stop American, British and French airlifts of food and other provisions to the Western-held sectors of Berlin following the Soviet blockade.

Origins

Postwar division of Germany

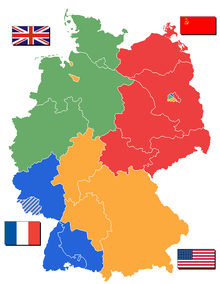

When World War II ended in Europe on May 8, 1945, Soviet and Western (U.S., British, and French) troops were located in particular places, essentially, along a line in the center of Europe. From July 17 to August 2, 1945, the victorious Allied Powers reached the Potsdam Agreement on the fate of postwar Europe, calling for the division of a defeated Germany into four occupation zones (thus reaffirming principles laid out earlier by the Yalta Conference), and the similar division of Berlin into four zones. The French, American, and British sectors of Berlin were deep within the Soviet occupation zones. The three Western-held sectors of Berlin quicky became a focal point of tensions corresponding to the breakdown of the U.S.-Soviet wartime alliance. (See Cold War (1947-1953))

The dispute over Berlin

The Berlin blockade had its roots in 1945 and 1946, when the breakdown of the Four Power Allied Control Council rendered the reunification of postwar Germany impossible.

The Soviets sought to create a unified but demilitarized Germany under their tutelage, or as Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov told U.S. Secretary of State James F. Byrnes in 1946, a united Germany that could be neutralized after Russia received industrial reparations from Germany. This strategy was a response to a 150-year history of repeated Western assaults on Russia, including World War I and Napoleon's 1812 invasion. Stalin considered it essential to destroy Germany's capacity for another war, which conflicted with the U.S. desire to rebuild Germany as the economic center of a stable Europe. (Stalin assumed that Japan and Germany could menace the Soviet Union once again following their postwar reconstruction.)

The United States, however, stressed that postwar reconstruction in Western Europe depended on German economic and industrial recovery. The U.S. stance was that if it could not reunify Germany with Soviet cooperation, the West could develop the western, industrial portions of postwar Germany controlled by France, Britain, and the U.S. and integrate the areas into a new European sphere.

Led by the U.S., the three major Western former Allied Powers reached an agreement on this approach during a series of impromptu meetings in London from February to June 1948. As outlined in an announcement on March 6, 1948, the London Conference declared support for fusing the three Western zones of Germany into an independent, federal form of government, and bringing the fusion of the three Western zones into the U.S.-led economic reconstruction efforts. (See Marshall Plan). These plans created a crisis in Soviet foreign policy, which was predicated on a weakened Germany and ensuring reparations payments.

In addition, the dispute over Germany escalated after U.S. President Harry S. Truman refused to give the Soviet Union reparations from West Germany's industrial plants; Stalin responded by splitting off the Soviet sector of Germany as a Communist state.

The Berlin Airlift

On June 24, 1948, the Soviet Union blocked access to the three Western-held sectors of Berlin, which was deep within the Soviet zone of Germany, by cutting off all rail and road routes going through Soviet-controlled territory in Germany, and the Western powers had never negotiated a pact with the Soviets guaranteeing these rights. Amid the fallout of the London Conference, the Soviets now rejected arguments that occupation rights in Berlin and the use of the routes during the previous three years had given the West legal claim to unimpeded use of the highways and railroads.

The commander of the American occupation zone in Germany, General Lucius D. Clay, proposed sending a large armoured column driving peacefully, as a moral right, down the Autobahn from West Germany to West Berlin, but prepared to defend itself if it were stopped or attacked. President Harry S. Truman, however, following the consensus in Washington, believed this entailed an unacceptable risk of war. Truman stated, "It is too risky to engage in this due to the consequence of war". Clay was told to take advice from General Curtis LeMay, commander of United States Air Forces in Europe, to see if an airlift was possible. By chance, General Albert Wedemeyer, the U.S. Army Chief of Plans and Operations, was in Europe on an inspection tour when the crisis occurred. He had been commander of the U.S. China Theater in 1944–1945 and had an intimate knowledge of the World War II Allied airlift from India over the Hump of the Himalayas. He was in favour of the airlift option and knew the best person to run the operation: Lt. General William H. Tunner was charged with organizing and commanding the Berlin airlift because of his experience in commanding and organizing the airlift over the Hump.[1]

Talking to the British Royal Air Force about the possibilities of an allied airlift it was revealed they were already running an airlift to the support of their own troops and that they were positive on the plan. During the earlier "Small Berlin Blockade" in early 1948 the British Air Commodore Rex Waite has been calculating over the required resources which did show that in the case of another blockade it would be possible to not only support his own troops but the whole city. Given these numbers the three allies were instantly agreeing to start the airlift without delay.

On June 25 Clay gave the order to launch a massive airlift using both civil and military aircraft (ultimately lasting 462 days) that flew supplies into the Western-held sectors of Berlin over the blockade during 1948–1949. The first plane flew on the following day, and the first British aeroplane flew on the 28th. This aerial supplying of West Berlin became known as the Berlin Airlift. Military confrontation loomed while Truman embarked on a highly visible move which would publicly humiliate the Soviets. The U.S. action was given the name "Operation Vittles," and the British one was called "Plain Fare."

Next to the British and US troops there were pilots from Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa running the airlift. The French Air Force however was fully consumed in the First Indochina War (1946-1954) so they could just bring up some old Ju52 to support their own troops. However they agreed to build a new and larger airport in their sector on the shores of Lake Tegel. The French military engineers were able to complete the construction in less than 90 days. The airfield evolved after the crisis into the Berlin-Tegel International Airport, the largest airport of the town today.

Hundreds of aircraft, nicknamed Rosinenbomber ("raisin bombers") by the local population, were used to fly in a wide variety of cargo, ranging from large containers to small packets of candy with tiny individual parachutes intended for the children of Berlin (an idea of a pilot named Gail Halvorsen that soon gained popular support in the U.S.). Sick children were evacuated on return flights. The aircraft were supplied and flown by the United States, United Kingdom and France, but pilots and crew also came from Australia, Canada, South Africa and New Zealand in order to assist the supply of Berlin. Ultimately 278,228 flights were made and 2,326,406 tons of food and supplies, including more than 1.5 million tons of coal, were delivered to Berlin.[1]

On April 4, 1949, the Western powers signed the North Atlantic Treaty founding NATO, declaring that an attack on any one would be considered an attack against them all.

At the height of the operation, on April 16 1949, an allied aircraft landed in Berlin every minute, with 1,398 flights in 24 hours carrying 12,940 tons (13,160 t) of goods, coal and machinery, beating the record of 8,246 (8,385 t) set only days earlier.

The USSR lifted its blockade at midnight, on May 11, 1949. However, the airlift did not end until September 30, as the Western states wanted to build up sufficient amounts of supplies in West Berlin in case the Soviets blockaded it again.

The three major Berlin airfields involved were Tempelhof, in the American Sector, Gatow in the British and Tegel in the French. Operational control of the three allied airlift corridors was given to BARTCC (Berlin Air Route Traffic Control Center) air traffic control located at Tempelhof. Diplomatic approval authority was granted to a secretive four-power organization also located in the American sector. It was called the Berlin Air Safety Center (BASC).

British operation

Initially the British had about 150 C-47 Dakotas and 40 Avro Yorks. By July 18, the RAF was flying 5538 tons of supplies per day into Berlin. In July, the Dakotas and Yorks were joined by 10 Short Sunderland and Short Hythe flying boats, flying from the Elbe near Hamburg to the Havel river. The flying boats' speciality was transporting bulk salt, which would have been corrosive to the other planes. In November, Handley Page Hastings were added to the fleet and some crews and aircraft were removed to train others. By mid-December, the RAF had landed 100,000 tons of supplies. In April 1949, civilian companies involved in the airlift were formed into a Civil Airlift Division (of British European Airways) to operate under RAF co

See also

- History of Germany

- West Berlin

- RAF Gatow

- East Berlin

- Gail Halvorsen (also known as "Uncle Wiggle Wings the Candy Bomber")

- The Big Lift, a 1950 film about the airlift from an American point of view.

References

- Robert E. Griffin and D. M. Giangreco, Airbridge to Berlin : The Berlin Crisis of 1948, Its Origins and Aftermath, Presidio Press, 1988. ISBN 0-89141-329-4

Further reading

- Operation Plainfare

- Luftbruecke: Allied Culture in the Heart of Berlin

- Agreement to divide Berlin

- Memorandum for the President: The Situation in Germany, July 23, 1948

- Berlin Airlift: Logistics, Humanitarian Aid, and Strategic Success

- Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and the Cold War (Berlin Airlift)

Footnotes

- ^ * D.M. Giangreco, D.M and Griffin, Robert E.; (1988) The Airlift Begins on Truman Library website, a Chapter section from: Airbridge to Berlin --- The Berlin Crisis of 1948, its Origins and Aftermath.