History of Catholic Mariology

| Part of a series on the |

| Mariology of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Catholic Mariology traces theological developments and views regarding Mary from the early Church to the 21st century. Mariology is a mainly Catholic ecclesiological study within theology, which centers on the relation of Mary, the Mother of God, and the Church. Theologically, it not only deals with her life but with her veneration in life and prayer, in art, music, and architecture, from ancient Christianity to modern times.

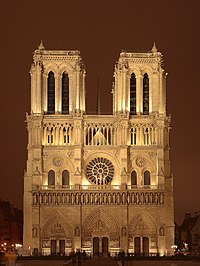

Throughout history, Catholics have continued to build churches to honor the Blessed Virgin. Today, many Catholic churches dedicated to the Blessed Virgin exist on all continents and, in a sense, their evolving architecture tells the unfolding story of the development of Catholic Mariology. Throughout Catholic history, the veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary has led to the creation of numerous items of Roman Catholic Marian art. Today, these items may be viewed from an artistic perspective, but also they are part of the fabric of Catholic Mariology.

Mary in the Early Church

[edit]

"Many centuries were necessary to arrive at the explicit definition of the revealed truths concerning Mary," said Pope John Paul II in 1995.[1] The importance of Mary and of Marian theology can be seen in the Church after the third century. The New Testament Gospels, composed during the late 1st century, contain the first references to the life of Mary; the New Testament Epistles, composed earlier, make no mention of her by name. There are, however, references to Mary in the Epistles, most notably in Galatians.[2][3] In the 2nd century, St. Irenaeus of Lyons called Mary the "second Eve" because through Mary and her willing acceptance of God's choice, God undid the harm that was done through Eve's choice to eat the forbidden fruit. The earliest recorded prayer to Mary is the sub tuum praesidium (3rd or 4th century) and the earliest depictions of her are from the Priscilla catacombs in Rome (early 3rd century).

Hugo Rahner's 20th-century discovery and reconstruction of Saint Ambrose's 4th-century view of Mary as the Mother of the Church was adopted at the Second Vatican Council. This shows the influence of early traditions and views on Mary in modern times.[4][5][6] This view was emphasized by Pope John Paul II in 1997, and today Mary is viewed as the Mother of the Church by many Catholics, and also as the Queen of Heaven.[7]

In the 5th century, the Third Ecumenical Council debated the question of whether Mary should be referred to as Theotokos or Christotokos.[8] Theotokos means "God-bearer" or "Mother of God"; its use implies that Jesus, to whom Mary gave birth, is truly God and man in one person. Nestorians preferred the title Christotokos meaning "Christ-bearer" or "Mother of the Messiah" not because they denied Jesus' divinity, but because they believed that God the Son or Logos existed before time and before Mary, and that Mary was mother only of Jesus as a human, so calling her "Mother of God" was confusing and potentially heretical. Both sides agreed that Jesus took divinity from God the Father and humanity from his mother. The majority at the council agreed with the Pope that denying Mary the title Theotokos would either imply that Jesus was not divine, or that Jesus had two separate personhoods, one of whom was son of Mary and the other not. Ultimately, the council affirmed the use of the title Theotokos and by doing so affirmed Jesus' undivided divinity and humanity.

Thus, while the debate was over the proper title for Mary, it was primarily a Christological question about the nature of Jesus Christ, a question which would return at the Fourth Ecumenical Council. Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Lutheran and Anglican theological teaching affirms the title Mother of God, while other Christian denominations give no such title to her.

Medieval Mariology

[edit]

The Middle Ages saw a growth and development of Mariology. Belief in the Assumption of Mary became widespread across the Christian world from the 6th century onward, and is celebrated on 15 August in both the East and the West.[9] The Medieval period brought major champions of Marian devotion to the fore, including Ephraim the Syrian and John Damascene.

The Dogma of the Immaculate Conception developed within the Catholic Church over time. The Conception of Mary was celebrated as a liturgical feast in England from the 9th century, and the doctrine of her "holy" or "immaculate" conception was first formulated in a tract by Eadmer, companion and biographer of Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury.[10] The Normans suppressed the Anglo-Saxon celebration, but it lived on in the popular mind.

The majority of Western Marian writers during this period belonged to the monastic tradition, particularly the Benedictines. The twelfth and thirteenth centuries saw an extraordinary growth of the cult of the Virgin in western Europe, in part inspired by the writings of theologians such as Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153).[11] One of the most influential churchmen of his time, in his "Sermon on the Sunday in the Octave of the Assumption" he described Mary's participation in redemption.[12] Bernard's Praises on the Virgin Mother was a small but complete treatise on Mariology.[13] Pope Pius XII's 1953 encyclical Doctor Mellifluus, issued in commemoration of the eighth centenary of Bernard's death, quotes extensively from Bernard's sermon on Mary as "Our Lady, Star of the Sea".[14]

Western types of the Virgin's image, such as the twelfth-century “Throne of Wisdom”, in which the Christ Child is presented frontally as the sum of divine wisdom, seem to have originated in Byzantium.[11] This was much used in Early Netherlandish painting in works like the Lucca Madonna by Jan van Eyck.

Theologically, one major controversy of the age was the Immaculate Conception. It was rejected by Bernard of Clairvaux, Alexander of Hales, and Bonaventure (who, teaching at Paris, called it "this foreign doctrine", indicating its association with England), and by Thomas Aquinas who expressed questions about the subject, but said that he would accept the determination of the Church. Aquinas and Bonaventure, for example, believed that Mary was completely free from sin, but that she was not given this grace at the instant of her conception. Anthony of Padua (1195–1231) supported Mary's freedom from sin and her Immaculate Conception.[15][16] His many sermons on the Virgin Mary shaped the Mariological approach of many Franciscans who followed his approach for centuries after his death.[17]

Oxford Franciscans William of Ware and especially John Duns Scotus defended the doctrine. Scotus proposed a solution to the theological problem of reconciling the doctrine with that of the universal redemption in Christ, by arguing that Mary's immaculate conception did not remove her from redemption by Christ. Rather it was the result of a more perfect redemption given to her on account of her special role in history. Furthermore, Scotus said that Mary was redeemed in anticipation of Christ's death on the cross.[18] Scotus' defense of the immaculist thesis was summed up by one of his followers as potuit, decuit ergo fecit – God could do it, it was fitting that He did it, and so He did it. Gradually the idea that Mary had been cleansed of original sin at the very moment of her conception began to predominate, particularly after Duns Scotus dealt with the major objection to Mary's sinlessness from conception, that being her need for redemption.[19] The very divine act, in making Mary sinless at the first instant of her conception was, he argued, the most perfect form of redemption possible.

By the end of the Middle Ages, Marian feasts were firmly established in the calendar of the liturgical year. Pope Clement IV (1265–1268) created a poem on the seven joys of Mary, which in its form is considered an early version of the Franciscan rosary[20]

Renaissance to Baroque

[edit]

Beginning in the 13th century, the Renaissance period witnessed a dramatic growth in Marian art, by masters such as Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael.[21] Some was specifically produced to decorate the Marian churches built in this period.

Paintings of the Madonna and Child were enormously popular in 15th-century Italy.[22] Major Italian artists with Marian motifs include: Fra Angelico, Donatello, Sandro Botticelli, Masaccio, Filippo Lippi, Piero di Cosimo Paolo Uccello Antonello da Messina Andrea Mantegna, Piero della Francesca and Carlo Crivelli.

Dutch and German artists with Marian paintings include: Jean Bellegambe, Hieronymus Bosch, Petrus Christus, Gerard David, Hubert van Eyck, Geertgen tot Sint Jans, Quentin Matsys, Rogier van der Weyden, Hans Baldung and Albrecht Dürer. Albrecht Altdorfer's Nativity of the Virgin symbolized the analogy between Mary and the Church.[23]

French and Spanish artists with Marian paintings include: Jean Fouquet, Jean Clouet, François Clouet, Barthélemy d'Eyck, Jean Hey, Bartolomé Bermejo, Ayne Bru, Juan de Flandes, Jaume Huguet, and Paolo da San Leocadio.

Francis of Assisi is credited with setting up the first known presepio or crèche (Nativity scene).[24] The influence of the Franciscans gave rise to a more affective spirituality. Pope Sixtus IV, a Franciscan, greatly increased the prominence given to Mary, introducing the Presentation of Mary (1472) and extending the Feast of the Visitation, for the whole church (1475), and introducing the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, observed by the Franciscans since 1263 but strenuously opposed by the Dominicans and still highly-controversial in the fifteenth century.[25] Around the time of the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 many Orthodox monks fled to the West, bringing with them traditions of iconography. Depictions of the Madonna and Child can be traced to the Eastern Theotokos. In the Western tradition, depictions of the Madonna were greatly diversified by Renaissance masters such as Duccio, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giovanni Bellini, Caravaggio and Rubens. The early Renaissance saw an increased emphasis on Christ crucified and therefore Mary as the Sorrowful Mother, an object of compassionate devotion.[26] Artists such as Titian depicted Mary as the Mater Dolorosa.

With the Protestant Reformation, Roman Catholic Mariology came under attack as being sacrilegious and superstitious.[27] Protestant leaders like Martin Luther and John Calvin, while personally adhering to Marian beliefs like virgin birth and sinlessness, considered Catholic veneration of Mary as competition to the divine role of Jesus Christ.

As a reflection of this theological opposition, Protestant reformers destroyed much religious art and Marian statues and paintings in churches in northern Europe and England. Some of the Protestant reformers, in particular Andreas Karlstadt, Huldrych Zwingli and John Calvin, encouraged the removal of religious images by invoking the Decalogue's prohibition of idolatry and the manufacture of graven images of God. Major iconoclastic riots took place in Zürich (in 1523), Copenhagen (1530), Münster (1534), Geneva (1535), Augsburg (1537), and Scotland (1559). Protestant iconoclasm swept through the Seventeen Provinces (now the Netherlands and Belgium and parts of Northern France) in the summer of 1566. In the middle of the 16th century, the Council of Trent confirmed the Catholic tradition of paintings and artworks in churches. This resulted in a great development of Marian art and Mariology during the Baroque Period.

At the same time, the Catholic world was engaged in ongoing Ottoman Wars in Europe against Turkey which were fought under the auspices of the Virgin Mary. The victory at Battle of Lepanto (1571) was accredited to her "and signified the beginning of a strong resurgence of Marian devotions, focusing especially on Mary, the Queen of Heaven and Earth and her powerful role as mediator of many graces".[28] The Colloquium Marianum, an elite group, and the Sodality of Our Lady based their activities on a virtuous life, free of cardinal sins.

The baroque literature on Mary experienced unforeseen growth with over 500 pages of Mariological writings during the 17th century alone.[29] The Jesuit Francisco Suárez (1548-1617) was the first theologian who used the Thomist method on Mariology and is considered the father of systematic Mariology.[18] Other well-known contributors to baroque Mariology are Lawrence of Brindisi, Robert Bellarmine, and Francis of Sales. After 1650, the Immaculate Conception is the subject of over 300 publications from Jesuit authors alone.[30]

This popularity was at times accompanied with Marian excesses and alleged revelations of the Virgin Mary to individuals like María de Ágreda.[31] Many of the baroque authors defended Marian spirituality and Mariology. In France, the often anti-Marian Jansenists were combated by John Eudes and Louis de Montfort.[32]

Baroque Mariology was supported by several popes during the period: Popes Paul V and Gregory XV ruled in 1617 and 1622 that it is inadmissible to state that the virgin was conceived non-immaculate. Alexander VII declared in 1661 that the soul of Mary was free from original sin. Pope Clement XI ordered the feast of the Immaculata for the whole Church in 1708. The feast of the Rosary was introduced in 1716 and the feast of the Seven Sorrows in 1727. The Angelus prayer was strongly supported by Pope Benedict XIII in 1724 and by Pope Benedict XIV in 1742.[33]

Popular Marian piety was more colorful and varied than ever before: Numerous Marian pilgrimages, Marian Salve devotions, new litanies, Marian theatre plays, Marian hymns, Marian processions. Marian fraternities, today mostly defunct, had millions of members.[34] Lasting impressions from the baroque Mariology are in the field of classical music, painting and art, architecture, and in the numerous Marian shrines from the baroque period in Spain, France, Italy, Austria and Bavaria as also in some South American cities.

Mariology during the Enlightenment

[edit]

During the Age of Enlightenment, the emphasis on scientific progress and rationalism put Catholic theology and Mariology on the defensive. The Church continued to stress the virginity and special graces, but deemphasized Marian cults.[35] During this period, Marian theology was even discontinued in some seminaries (for example: in Salzburg Austria in the year 1782[36]). Some theologians proposed the abolition of all Marian feast days altogether, except those with biblical foundations and the feast of the Assumption.[37]

Nonetheless, in this period a number of significant Marian churches were built, often laden with Marian symbols, and popular Marian devotions continued in many areas. An example is Santa Maria della Salute in Venice, built to thank the Virgin Mary for the city's deliverance from the plague. The church is full of Marian symbolism: the great dome represents her crown, and the eight sides, the eight points on her symbolic star.

Many Benedictines such as Celestino Sfondrati (died 1696) and Jesuits,[38] supported by pious faithful and their movements and societies, fought against the anti-Marian trends. Increasing secularization led to the forced closing of most monasteries and convents, and Marian pilgrimages were either discontinued or greatly reduced in number. Some Catholics criticized the practice of the Rosary as not Jesus-oriented and too mechanical.[39] In some places, priests forbade the praying of the Rosary during Mass.[40] The highly conservative rural Bavarian dioceses of Passau outlawed Marian prayer books and related articles in 1785.[39]

During this time, Mariologists looked to The Glories of Mary and other Mariological writings of Alphonsus Liguori (1696–1787), an Italian, whose culture was less affected by the Enlightenment. "Overall, Catholic Mariology during the Enlightenment lost its high level of development and sophistication, but the basics were kept, on which the 19th century was able to build."[41]

Mariology in the 19th century

[edit]

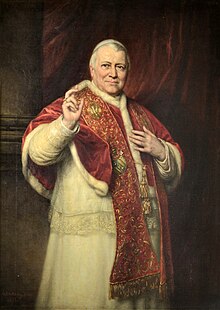

Mariology in the 19th century was dominated by discussions about the dogmatic definition of the Immaculate Conception and the First Vatican Council. In 1854, Pope Pius IX, with the support of the overwhelming majority of Roman Catholic bishops whom he had consulted between 1851 and 1853, proclaimed the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, which had been a traditional belief among the faithful for centuries.[42]

Eight years earlier, in 1846, the Pope had granted the unanimous wish of the bishops from the United States, and declared the Immaculata the patron of the US.[43] During the First Vatican Council, some 108 council fathers requested adding the words "Immaculate Virgin" to the Hail Mary prayer and to add the Immaculata to the Litany of Loreto. Some fathers requested the dogma of the Immaculate Conception to be included in the Creed of the Church.[44]

Many French Catholics supported making dogma both Papal infallibility and the assumption of Mary in the forthcoming ecumenical council.[45] During the First Vatican Council, nine Mariological petitions favored a possible Assumption dogma. It was strongly opposed by some council fathers, especially those from Germany. On 8 May, a majority of the fathers voted to reject making the Assumption a dogma, a position shared by Pope Pius IX. The concept of Co-Redemptrix was also discussed but left open. In its support, Council fathers highlighted the divine motherhood of Mary and called her the mother of all graces.[46]

"Rosary Pope" is a title given to Pope Leo XIII (1878–1903) because he issued a record eleven encyclicals on the Rosary, instituted the Catholic custom of daily Rosary prayer during the month of October, and in 1883 created the Feast of Queen of the Holy Rosary.[47]

John Henry Newman, wrote of the Eve-Mary parallel in support of Mary's original state of grace (Immaculate Conception), her part in redemption, her eschatological fulfilment and her intercession.[48]

Popular opinion remained firmly behind the celebration of Mary's immaculate conception. The doctrine itself had been endorsed by the Council of Basel (1431–1449), and by the end of the 15th century was widely professed and taught in many theological faculties. The Council of Basel was later held not to have been a true General (or Ecumenical) Council with authority to proclaim dogma. Such was the influence of the Dominicans, and the weight of the arguments of Thomas Aquinas (who had been canonised in 1323 and declared "Doctor Angelicus" of the Church in 1567) that the Council of Trent (1545–63) – which might have been expected to affirm the doctrine – instead declined to take a position. It simply reaffirmed the constitutions of Sixtus IV, which had threatened with excommunication anyone on either side of the controversy who accused the others of heresy.

But it was not until 1854 that Pope Pius IX, with the support of the overwhelming majority of Roman Catholic bishops, whom he had consulted between 1851 and 1853, proclaimed the doctrine in accordance with the conditions of papal infallibility that would be defined in 1870 by the First Vatican Council.

Mariology in the 20th century

[edit]In 1904, in the first year of his pontificate, Pope Pius X celebrated the previous century's proclamation of the dogma of Immaculate Conception with the encyclical Ad diem illum. In 1950, the dogma of the Assumption was defined by Pope Pius XII. The Second Vatican Council spoke of Mary as Mother of the Church. Pope Pius XI presided over a Mariological congress in 1931.[49]

Mariology in the 20th century reflected an increased membership in Roman Catholic Marian Movements and Societies. At the popular level, the 20th century witnessed growth in the number of lay Marian devotional organizations such as free Rosary distribution groups. The number of 20th century pilgrims visiting Marian churches set new records. In South America alone, two major Marian basilicas, the Basilica of the National Shrine of Our Lady of Aparecida in Brazil and the new Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe on Tepeyac hill, were constructed and jointly recorded over 10 million visitors per year.

Prior to Vatican II, the French Mariological Society held a three-year series of Marian studies on the theme of Mary in relation to the Church.[50]

Second Vatican Council

[edit]Mariological issues were included in the discussions at the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), although the Council indicated that it had not addressed all Marian issues. The Council members had in depth discussions regarding the question of whether to treat Mary within the Constitution of the Church or outside it in a separate document.[51] The final decision, by a vote of 1114–1074, resulted in the treatment of Marian issues within the Church Constitution, as chapter eight of Lumen gentium.[51] This chapter provides a "pastoral summary" of Catholic doctrines on Mary but does not claim to be complete.[52]

At the conclusion of the Vatican II Council in December 1965, Catholics were presented with a multitude of changes. Some authors such as John W. O'Malley have commented that these issues would forever alter Catholic practices and views, including those surrounding the Virgin Mary. These changes reflected the council's desire to make the Church more ecumenical and less isolated as it increasingly had become in the past century.[53] One of the roadblocks towards finding common ground was the complaint by other faiths regarding the Church's dogmas on the Virgin Mary, and especially the fervor of the Catholic laity to preserve Mary at the center of their devotions.[53][54][55]

The preparations for the council included an independent schema "About the Blessed Virgin Mary, mother of God and Mother of the People".[52] Some observers interpreted the renunciation of this document on Mary as minimalism, others interpreted her inclusion as a chapter into the Church document as underlining her role for the Church.[52] With the inclusion of Marian issues within the Constitution of the Church rather than in a separate document, at Vatican II the contextual view of Mary was emphasized, namely that Mary belongs "within the Church":[56]

- For having been the Associate of Christ on earth

- For being a Heavenly mother to all members of the Church in the order of grace

- For having been the model disciple, a model which every member of the Church should aim to imitate.[56]

Calling Mary "our mother in the order of grace", Lumen gentium referred to Mary as a model for the Church and stated that:[57]

By reason of the gift and role of divine maternity, by which she is united with her Son, the Redeemer, and with His singular graces and functions, the Blessed Virgin is also intimately united with the Church. As St. Ambrose taught, the Mother of God is a type of the Church in the order of faith, charity and perfect union with Christ.[58]

The Marian chapter has five parts which link Mary to the salvation mysteries which continue in the Church, which Christ has founded as his mystical body. Her role in relation to her son is a subordinate one. Highlighted are her personality and fullness of grace. The second part describes her role in salvation history. Her role as a mediator is detailed, as Mary is considered to secure our salvation through her many intercessions after her assumption into heaven. The Council refused to adopt the title mediator of all graces and emphasized that Christ is the one mediator.[59] Pope Paul VI declared Mary Mother of the Church during the Vatican Council.

Late 20th century

[edit]Following Vatican II, the perception that Marian devotions had decreased was expressed by several authors. Other authors have indicated that the continued strength of devotion to Mary within Catholicism following Vatican II has been manifested in multiple forms worldwide.[60] Examples of this are the increase in Marian pilgrimages at major Marian shrines and the construction of major new Marian Basilicas since Vatican II.[60]

At the end of the 20th century, two of the top three most visited Catholic shrines in the world were Marian, with the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City, built between 1974 and 1976, being the most visited Catholic shrine in the world.[61] In 1968, shortly after Vatican II, the Basilica of the National Shrine of Our Lady of Aparecida in Brazil used to receive about four million pilgrims per year, but the number has since doubled to over eight million pilgrims per year, indicating the significant increase in Marian pilgrimages since Vatican II.[60][62][63]

The perceived impact of concessions to ecumenism made at Vatican II did not impact the fundamental loyalties to Mary among Catholics and their attachment to Marian veneration.[56] A 1998 survey among young adult Catholics in the United States provided the following results:

- Devotion to Mary had not been reduced in any significant manner since Vatican II, despite the various statements made about its perceived impact on Catholics.

- Young Catholics stated that in their view the "passionate love of God" is revealed through Mary, possibly as a result of the Marian emphasis of the pontificate of Pope John Paul II.

- Mary continues to be a "distinctive marker" of the Catholic identity.[56]

Papal extensions and enhancement to the Mariology of Vatican II continued shortly thereafter, with Pope Paul VI issuing the Apostolic Exhortation Marialis Cultus (to Honor Mary) in 1974, which took four years to prepare.[51][64][65] Marialis Cultus provided four separate guidelines for the renewal of Marian veneration, the last two of which were new in Papal teachings. The four elements were: biblical, liturgical, ecumenical and anthropological.[51][64]

Marian devotions were the hallmark of the pontificate of Pope John Paul II and he reoriented the Catholic Church towards the renewal of Marian veneration.[66][4] In March 1987 he went further than Paul VI in extending the Catholic views on Mary beyond Vatican II by issuing the encyclical Redemptoris Mater.[51][67] Rather than being just a new presentation of the Marian views of Vatican II, Redemptoris Mater was in many aspects a re-reading, re-interpretation and further extension of the teachings of Vatican II.[51][68]

In 1988 in Mulieris Dignitatem Pope John Paul II stated that the Second Vatican Council confirmed that: "unless one looks to the Mother of God, it is impossible to understand the mystery of the Church".[69][70] In 2002 in the Apostolic letter Rosarium Virginis Mariae he emphasized the importance of the Rosary as a key devotion for all Catholics and added the Luminous Mysteries to the Rosary.[66][71] By 2005, when he died, he had inspired a worldwide renewal of Marian devotions, that was reflected upon on the occasion of his death within non-Catholic media such as U.S. News & World Report.[56]

21st century

[edit]Pope Benedict XVI continued the program of redirection of the Catholic Church towards a Marian focus and stated: "Let us carry on and imitate Mary, a deeply Eucharistic soul, and our lives will become a Magnificat".[4] In 2008 Benedict composed a prayer on Mary as the Mother of all Christians:[72]

- You became, in a new way, the Mother of all those who receive your Son Jesus in faith and choose to follow in his footsteps.[73]

Benedict journeyed to Marian shrines such as Lourdes and Fatima to support his message.[74][75]

See also

[edit]- Acts of Reparation to the Virgin Mary

- Mariology (Roman Catholic)

- Mariology of the popes

- Mariology of the saints

- Mariology Ecumenical views

- Protestant views of Mary

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pope John Paul II, "General Audience", 8 November 1995

- ^ Sr. M. Danielle Peters, "An Overview of New Testament References," The Mary Page, retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Galatians 4:4, "But when the fullness of the time came, God sent forth His Son, born of a woman, born under the Law" (NASB)

- ^ a b c Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, Seminarians, and Consecrated Persons, (Mark I. Miravalle, ed.) Queenship Publishing, 2008 ISBN 9781579183554 p. 587

- ^ O'Donnell, Timothy Terrance. Heart of the Redeemer, 1992 ISBN 0-89870-396-4 p. 83

- ^ Lumen gentium, Chapter 8 Archived 6 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Blessed Virgin is Mother of the Church". L'Osservatore Romano. 24 September 1997. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Braaten Carl E., and Jenson, Robert W. Mary, Mother of God, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-2266-5 p. 84

- ^ Butler, Alban and Burns, Paul. Butler's Lives of the Saints, 1998 ISBN 0-86012-257-3 pp. 140-141

- ^ Knowles, David. The Monastic Order in England (Cambridge, 1941), pp. 510-14.

- ^ a b "Met Museum". metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Pope Benedict XVI. "General Audience", 21 October 2009, L'Osservatore Romano, 28 October 2009, p. 24

- ^ Duignan, Brian. Medieval Philosophy, The Rosen Publishing Group, 2011 ISBN 978-1-61530-143-0

- ^ Hom. II super "Missus est," 17; Migne, P. L., CLXXXIII, 70-b, c, d, 71-a. Quoted in Doctor Mellifluus 31

- ^ Huber, Raphael Mary, St. Anthony of Padua: Doctor of the Church Universal, 1948 ISBN 1-4367-1275-0 p. 31

- ^ Huber, Raphael M. “The Mariology of St. Anthony of Padua,” in Studia Mariana 7, Proceedings of the First Franciscan National Marian Congress in Acclamation of the Dogma of the Assumption, October 8–11, 1950 Burlington, Wisconsin

- ^ Kleinhenz, Christopher. Medieval Italy: an encyclopedia, Vol. 1, 2003 ISBN 0-415-93930-5 p. 40

- ^ a b "Fastiggi, Robert. "11 questions answered about Mary", OSV Newsweekly, April 29, 2015". Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ Ludwig Ott, Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, Mercier Press Ltd., Cork, Ireland, 1955

- ^ Otto Stegmüller Clemens IV in Marienkunde, 1159

- ^ Renaissance Art: A Very Short Introduction by Geraldine A. Johnson 2005 ISBN 0-19-280354-9 pages 103-104

- ^ Lightbown, Ronald. Sandro Botticelli: Life and Work, 1989, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-09206-4

- ^ Zuffi, Stefano (2005). Il Cinquecento. Milan: Electa. ISBN 9788837034689.

- ^ Robson, Michael J., The Cambridge Companion to Francis of Assisi, Cambridge University Press, 2011 ISBN 9780521760430

- ^ Hollingsworth, Mary, Patronage in Renaissance Italy, John Murray, 1994 ISBN 0719549264

- ^ Viladesau, Richard. The Triumph of the Cross, Oxford University Press, 2008 ISBN 9780199887378

- ^ "Ecclesiological History of Mariology : University of Dayton, Ohio". udayton.edu. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Otto Stegmüller, Barock, in Marienkunde, 1967 566

- ^ A Roskovany, conceptu immacolata ex monumentis omnium seculrorum demonstrate III, Budapest 1873

- ^ Otto Stegmüller, Mariologisches Schrifttum in der Barockzeit, 1967 568

- ^ who was placed on the Index of forbidden book of the Church in 1681.

- ^ (Stegmüller, 573)

- ^ F Zöpfl, Barocke Frömmigkeit, in Marienkunde, 577

- ^ Zöpfl 579

- ^ RG Giessler, die geistliche Lieddichting im Zeitalter der Aufklärung. 1928, 987

- ^ Narr Zoepfl Mariologie der Aufklärung, 1967, 411

- ^ Benedict Werkmeister, 1801

- ^ such as Anton Weissenbach SJ, Franz Neubauer SJ,

- ^ a b D Narr 417

- ^ In 1790, monastery schools outlawed the praying of the rosary during mass as a distraction. (D Narr 417).

- ^ Otto Stegmüller, 1967

- ^ Vatican website Archived 10 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pius IX in Bäumer, 245

- ^ Bauer 566

- ^ Civilta Catolica, 6 February 1869.

- ^ Bäumer 566

- ^ Lauretanische Litanei, Marienlexikon, St. Ottilien: Eos, 1988, p.41

- ^ Newman, John Henry. The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, ed. C. S. Dessain, Birmingham Oratory, 31 vols. (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1972), Vol. XII

- ^ Bäumer 534

- ^ "Marie et l’Eglise", ÉtMar 9-11 (1951-53), 3 Vols

- ^ a b c d e f Mary for Time and Eternity by William McLoughlin, Jill Pinnock 2007 ISBN 0-85244-651-9-page 66

- ^ a b c Leo Cardinal Scheffczyk, Vaticanum II, in Marienlexikon 567

- ^ a b What Happened at Vatican II, John W. O’Malley. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. London, 2008.

- ^ The Church: The Evolution of Catholicism. Richard P. McBrien. HarperOne. 2008

- ^ Vatican Council II: The Basic Sixteen Documents. Rev. Austin Flannery, O.P. Costello Publishing Company, 1996

- ^ a b c d e McNally, Terrence, What Every Catholic Should Know about Mary ISBN 1-4415-1051-6-page 30-32

- ^ "Dogmatic Constitution on the Church – Lumen gentium, 61". Archived from the original on 6 September 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ "Dogmatic Constitution on the Church – Lumen gentium, 63". Archived from the original on 6 September 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Leo Cardinal Scheffczyk, Vaticanum II, in Marienlexikon 569

- ^ a b c Mary in the plan of God and in the communion of the saints by Alain Blancy, Maurice Jourjon 2002 ISBN 0-8091-4069-1-page 46

- ^ "Shrine of Gualdalupe Most Popular in World". ZENIT International News Agency. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ Brazil rediscovered by Roberta C. Wigder 1977 ISBN 0-8059-2328-4-page 235

- ^ Pilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland : an encyclopedia, Volume 1 by Linda Kay Davidson, David Martin Gitlitz 2002 ISBN 1-57607-004-2 page 38

- ^ a b "Marialis Cultus (February 2, 1974) | Paul VI". vatican.va. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Magisterial Documents: Marialis Cultus : University of Dayton, Ohio". udayton.edu. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b John Paul II: a light for the world by Mary Ann Walsh 2003 ISBN 1-58051-142-2 p. 26

- ^ "Redemptoris Mater (25 March 1987) | John Paul II". vatican.va. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ The Vision of John Paul II by Gerard Mannion 2008 ISBN 0-8146-5309-X page 251

- ^ John Paul II's book of Mary by Pope John Paul II, Margaret Bunson 1996 ISBN 0-87973-578-3 page 81

- ^ Vatican website: Mulieris Dignitatem Archived 7 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Apostolic Letter Rosarium Virginis Mariae Archived 9 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Missing Page Redirect". cwnews.com. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Vatican website

- ^ "12 September 2008: Celebration of Vespers with priests, religious, seminarians and deacons gathered at Notre-Dame Cathedral (Paris) | BENEDICT XVI". vatican.va. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Vatican website: Pope Beneict XVI at Fatima Archived 14 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

References

[edit]- Michael Schmaus, Mariologie, Katholische Dogmatik, München Vol V, 1955

- K Algermissen, Boes, Egelhard, Feckes, Michael Schmaus, Lexikon der Marienkunde, Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg, 1967

- Mariology Society of America https://web.archive.org/web/20170925082500/http://mariologicalsocietyofamerica.us/

- The Marian Library at University of Dayton https://udayton.edu/imri/marian-library/index.php

- Pope Pius IX, Apostolic Constitution

- [Pope Pius XII], encyclicals and bulls

- Pope John Paul II, encyclical, apostolic letters and addresses

Further reading

[edit]- Gambero, Luigi. Mary and the Fathers of the Church: The Blessed Virgin Mary in Patristic Thought, trans. Thomas Buffer (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1999).

External links

[edit]- Rubin, Miri, Mother of God, Yale University Press, 2009 ISBN 9780300156133