Ramesses II

| Ramesses II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ramesses the Great alternatively transcribed as Ramses and Rameses | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

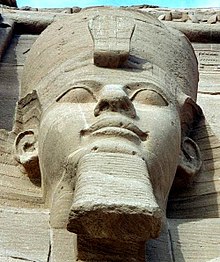

Ramesses II: one of four external seated statues at Abu Simbel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1279–1213 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Seti I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Merneptah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Henutmire, Isetnofret, Nefertari Maathorneferure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Khaemweset, Merneptah, Amun-her-khepsef, Meritamen, see also: List of children of Ramesses II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Seti I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Queen Tuya | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 1303 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1213 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | KV7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Abu Simbel, Ramesseum, Luxor and Karnak temples | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 19th Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ramesses II (also known as Ramesses The Great and alternatively (translation arabic: الملك رمسيس الثانيtranscribed as Ramses and Rameses *Riʕmīsisu; also known as Ozymandias in the Greek sources, from a transliteration into Greek of a part of Ramesses' throne name, User-maat-re Setep-en-re)[3] was the third Egyptian pharaoh of the Nineteenth dynasty. He is often regarded as Egypt's greatest and most powerful pharaoh.[4] He was born c. 1303 BC, the exact date being unknown (it has been said that he was born on February 22, though this is uncertain).[citation needed] At age fourteen, Ramesses was appointed Prince Regent by his father Seti I.[4] He is believed to have taken the throne in his early 20s and to have ruled Egypt from 1279 BC to 1213 BC[5] for a total of 66 years and 2 months, according to Manetho. He was once said to have lived to be 99 years old, but it is more likely that he died in his 90th or 91st year. If he became king in 1279 BC as most Egyptologists today believe, he would have assumed the throne on May 31, 1279 BC, based on his known accession date of III Shemu day 27.[6][7] Ramesses II celebrated an unprecedented 14 Sed festivals during his reign—more than any other pharaoh.[8]

Ancient Greek writers such as Herodotus attributed his accomplishments to the semi-mythical Sesostris. He is traditionally believed to have been the Pharaoh of the Exodus.

Family and life

Ramesses II was the third king of the 19th dynasty, and the second child of Seti I and his Queen Tuya.[9] His only definite sibling was Princess Tia, though in the case of Henutmire, one of his Great Royal Wives, she may the younger half-sister of Ramesses.[10]

Ramesses had numerous consorts, the most famous being was Nefertari.[citation needed] During his long reign, eight women held the title Great Royal Wife (often simultaneously): Nefertari and Isetnofret, whom he married early in his reign; Bintanath, Meritamen and Nebettawy, his own daughters who replaced their mothers Nefertari and Isetnofret when they died or retired; Henutmire; Maathorneferure, Princess of Hatti and another Hittite princess whose name did not survive.[11]

The writer Terence Gray stated in 1923 that Ramesses II had as many as 20 sons and 20 daughters but scholars today believe his offspring numbered over one hundred. In 2004, Dodson and Hilton noted that the monumental evidence "seems to indicate that Ramesses II had around 110 children, [with] 48-55 sons and 40-53 daughters."[12] His children include Bintanath and Meritamen (princesses and their father's wives), Sethnakhte, Amun-her-khepeshef the king's first born son, Merneptah (who would eventually succeed him as Ramesses' 13th son), and Prince Khaemweset. Ramesses II's second born son, Ramesses B, sometimes called Ramesses Junior, became the crown prince from Year 25 to Year 50 of his father's reign after the death of Amen-her-khepesh.[13]

As king, Ramesses II led several expeditions north into the lands east of the Mediterranean (the location of the modern Israel, Lebanon and Syria), he also lead expeditions to the south, into Nubia, commemorated in inscriptions at Beit el-Wali and Kalabsha.

Ramesses the Great accomplished many things in his life. His main focus before the Battle of Kadesh was building temples, monuments and cities. He established the city of Pi-Ramesses in the Nile Delta as his new capital and main base for the Hittite war. This city was built on the remains of the city of Avaris, the capital of the Hyksos when they took over. This is also where the Temple of Seti was located. This was a very significant place for Ramesses because this is where he supposedly harnesed the power of Set, Horus, Re, Amun, and his father Seti.[citation needed]

Campaigns and battles

Early in his life, Ramesses II embarked on numerous campaigns to return previously lost territories back to Egyptian hands and to secure Egypt's borders. By fighting more battles, he also contributed to the country's economy.[citation needed] He was also responsible for suppressing some Nubian revolts and carrying out a campaign in Libya. Although the famous Battle of Kadesh often dominates the scholarly view of Ramesses II's military prowess and power, he nevertheless did enjoy more than a few outright victories over the enemies and foes of Egypt.

- Battle against Sherden sea pirates

In his second year, Ramesses II decisively defeated the Shardana or Sherden sea pirates who were wreaking havoc along Egypt's Mediterranean coast by attacking cargo-laden vessels travelling the sea routes to Egypt.[14] The Sherden people came from the coast of Ionia or south-west Turkey, more likely Ionia. Ramesses posted troops and ships at strategic points along the coast and patiently allowed the pirates to attack their prey before skillfully catching them by surprise in a sea battle and capturing them all in one fell swoop.[15] A stela from Tanis speaks of their having come 'in their war-ships from the midst of the sea, and none were able to stand before them'. There must have been a naval battle somewhere near the river-mouths, for shortly afterwards many Sherden captives are seen in the Pharaoh's body-guard, where they are conspicuous by their helmets with horns with a ball projecting from the middle, their round shields and the great Naue II swords with which they are depicted in inscriptions of the Battle with the Hittites at Kadesh. Ramesses would soon incorporate these skilled mercenaries into his army where they were to play a pivotal role at the battle of Kadesh.[citation needed]

- First Syrian campaign

The immediate antecedents to the Battle of Kadesh were the early campaigns of Ramesses II into Canaan and Palestine. His first campaign seems to have taken place in the fourth year of his reign and was commemorated by the erection of a stela near Beirut (Be'erot). The inscription is almost totally illegible due to weathering. His records tell us that he was forced to fight a Palestinian prince who was mortally wounded by an Egyptian archer, and whose army was subsequently routed. Ramesses carried off the princes of Palestine as live prisoners to Egypt. Ramesses then plundered the chiefs of the Asiatics in their own lands, returning every year to his headquarters at Riblah to exact tribute. In the fourth year of his reign, he captured the Hittite vassal state of Amurru during his campaign in Syria.[16]

- Second Syrian campaign

The Battle of Kadesh was the major engagement in a campaign Ramesses fought in Syria, against the resurgent Hittite forces of Muwatalli. In order to fight his Hittite foes more effectivly, he incorporated as many men as possible into his army including the Sherden sea pirates whom he had captured just a few years earlier specifically for this climatic battle. Ramesses also constructed his new capital, Pi-Ramesses where he built factories to manufacture weapons, chariots, and shields, supposedly producing some 1,000 weapons in a week, about 250 chariots in 2 weeks, and 1,000 shields in a week and a half. Although outnumbered at Kadesh, Ramesses fought a stalemate and returned to home a hero. While Ramesses had in theory won the battle, he could not secure the victory and capture Kadesh due to his large battlefield losses.

Once back in Egypt, Ramesses proclaimed that he had won a great victory but in reality all he had managed to do was to rescue his army. In a sense, however, the Battle of Kadesh was a personal triumph for Ramesses since after blundering into a devastating Hittite ambush, the young king had courageously rallied his scattered troops to fight on the battlefield while escaping death or capture.

Ramesses decorated his monuments with reliefs and inscriptions describing the campaign as a whole, and the battle in particular as a major victory. For example, on the temple walls of Luxor the near catastrophe was turned into an act of heroism:

His majesty slaughtered the armed forces of the Hittites in their entirety, their great rulers and all their brothers [...] their infantry and chariot troops fell prostrate, one on top of the other. His majesty killed them [...] and they lay stretched out in front of their horses. But his majesty was alone, nobody accompanied him [...].[citation needed]

On other monuments, Ramesses states that he was not accompanied by his troops and that he had defeated the enemy by himself.[citation needed]

- Third Syrian campaign

Egypt's sphere of influence was now restricted to Canaan while Syria fell into Hittite hands. Canaanite princes, seemingly influenced by the Egyptian incapability to impose their will and goaded on by the Hittites, started revolting against Egypt. In the seventh year of his reign, Ramesses II returned to Syria once again. This time he proved more successful against his Hittite foes. On this campaign he split his army into two forces. One of these forces was led by his son, Amun-her-khepeshef, and it chased warriors of the Šhasu tribes across the Negev as far as the Dead Sea, and captured Edom-Seir. It then marched on to capture Moab. The other force, led by Ramesses, attacked Jerusalem and Jericho. He, too, then entered Moab, where he rejoined his son. The reunited army then marched on Hesbon, Damascus, on to Kumidi, and finally recaptured Upi.[citation needed]

- Later campaigns in Syria

Ramesses extended his military successes in his eighth and ninth years. He crossed the Dog River (Nahr el-Kelb) and pushed north into Amurru. His armies managed to march as far north as Dapur, where he erected a statue of himself. The Egyptian pharaoh thus found himself in northern Amurru, well past Kadesh, in Tunip, where no Egyptian soldier had been seen since the time of Thutmose III almost 120 years previously. He laid siege on the city before capturing it. His victory proved to be ephemeral. In year nine, Ramesses erected a stela at Beth Shean. After having reasserted his power over Canaan, Ramesses led his army north. A mostly illegible stela near Beirut, which appears to be dated to the king's second year, was probably set up there in his tenth.[citation needed] The thin strip of territory pinched between Amurru and Kadesh did not make for a stable possession. Within a year, they had returned to the Hittite fold, so that Ramesses had to march against Dapur once more in his tenth year. This time he claimed to have fought the battle without even bothering to put on his corslet until two hours after the battle began. Six of the sons of Ramsses, still wearing their side locks, took part in this conquest. He took towns in Retenu, and Tunip in Naharin. This second success here was equally as meaningless as his first since neither power could decisively defeat the other in battle.[citation needed]

- Peace treaty with the Hittites

The deposed Hittite king, Mursili III fled to Egypt, the land of his country's enemy, after the failure of his plots to oust his uncle from the throne. Hattusili III responded to this event by demanding that Ramesses II extradite his nephew back to Hatti.[citation needed]

This letter precipitated a crisis in relations between Egypt and Hatti when Ramesses denied any knowledge of Mursili's whereabouts in his country and the two Empires came dangerously close to war. Consequently, in the twenty-first year of his reign (1258 BC), Ramses decided to conclude an agreement with the new Hittite king at Kadesh, Hattusili III, to end the conflict. The ensuing document is the earliest known peace treaty in world history.[citation needed]

The peace treaty was recorded in two versions, one in Egyptian hieroglyphs, the other in Akkadian, using cuneiform script; fortunately, both versions survive. Such dual-language recording is common to many subsequent treaties. This treaty differs from others, however, in that the two language versions are differently worded. Although the majority of the text is identical, the Hittite version claims that the Egyptians came suing for peace, while the Egyptian version claims the reverse.[citation needed] The treaty was given to the Egyptians in the form of a silver plaque, and this "pocket-book" version was taken back to Egypt and carved into the Temple of Karnak.

The Treaty was concluded between Ramesses II and Hattusili III in Year 21 of Ramesses' reign.[17] (c.1258 BC) Its eighteen articles calls for peace between Egypt and Hatti and then proceeds to maintain that their respective gods also demand peace.

The frontiers are not laid down in this treaty but can be inferred from other documents. The Anastasy A papyrus describes Canaan during the latter part of the reign of Ramses II and enumerates and names the Phoenician coastal towns under Egyptian control. The harbour town of Sumur north of Byblos is mentioned as being the northern-most town belonging to Egypt, which points to it having contained an Egyptian garrison.[citation needed]

No further Egyptian campaigns in Canaan are mentioned after the conclusion of the peace treaty, the northern border seems to have been safe and quiet so the rule of the pharaoh was strong until the death of Ramesses II.[citation needed] When the king of Mira attempted to involve Ramses in a hostile act against the Hittites, the Egyptian responded that the times of intrigue in support of Mursili III, had passed. Hattusili III wrote to Kadashman-Enlil II, king of Karduniash (Babylon) in the same spirit, reminding him of the time when his father, Kadashman-Turgu, had offered to fight Ramesses II, the king of Egypt. The Hittite king encouraged the Babylonian to oppose another enemy, which must have been the king of Assyria whose allies had killed the messenger of the Egyptian king. Hattusili encouraged Kadashman-Enlil to come to his aid and prevent the Assyrians from cutting the link between the Canaanite province of Egypt and the ally of Ramesses.[citation needed]

- Campaigns in Nubia

Ramesses II also campaigned south of the first cataract into Nubia. When Ramesses was about 22, two of his own sons, including Amun-her-khepeshef, accompanied him in at least one one of those campaigns. By the time of Ramesses, Nubia had been a colony for two hundred years, but its conquest was recalled in decoration from the temples Ramesses II built at Beit el-Wali (It was the subject of epigraphic work by the Oriental Insitute during the Nubian salvage campaign of the 1960s.[citation needed]), Gerf Hussein and Kalabsha in Northern Nubia.

- Campaigns in Libya

During the reign of Ramesses II, we see evidence that the Egyptians were active for a 300km stretch along the Mediterranean coast, at least as far as Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham.[18] Whilst the exact events surrounding the foundation of the coastal forts and fortresses is not clear, some degree of political and military control must have been held over the region that allowed their construction. It must also have been foreseen that this would continue to allow the future maintenance of the settlements.[citation needed]

There are no detailed accounts of Ramesses II undertaking large military actions against the Libyans, only generalised records to his conquering and crushing them, which may or may not refer to specific events, otherwise unrecorded. It may be that some of the records, such as the Aswan Stela of his year 2, are harking back to Ramesses' presence on his father's Libyan campaigns. Perhaps it was Seti I who achieved this proposed control over the region, and it was he who planned to establish the defensive system, in a manner similar to which he rebuilt those to the east, the Ways of Horus across Northern Sinai. Ultimately, however, maybe it was his son who oversaw the project's completion, which would fit in well with a construction date early in the reign of Ramesses II, as suggested by the use of the early form of his name found at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham.[citation needed]

Religion and festivals

Ramesses the Great was the pharaoh most responsible for erasing the Amarna period from history.[citation needed] He, more than any other pharaoh, sought deliberately to deface the Amarna monuments and change the nature of the religious structure and the structure of the priesthood, in order to try to bring it back to where it had been prior to the reign of Akhenaten.

- Sed festival

When Ramesses had reigned for 30 years, he had joined a selected group that included only a handful of Egypt's longest lived kings. By tradition the 30th year of his reign Ramesses celebrated a traditional jubilee called the Sed festival, during which the king was ritually transformed into a god.[19] Only a half way through what would be a 66 year reign, Ramesses had already eclipsed all but a few greatest kings in his achevements. He had brought peace, maintained Egyptian borders and built great and numerous monuments across the empire. His country was more prosperous and powerful than it had been in nearly a century. By becoming a god, Ramesses dramatically changed not just his role as ruler of Egypt, but also the role of his firstborn son, Amun-her-khepsef. As chosen heir and commander and chief of Egyptian armies, his son become a ruler of land and effective ruler in all but name.

- Min Festival

This ancient festival, dating back to pre-dynastic Egypt,[20] was still very popular during Ramesses II's time. It was connected with the worship of the king and was carried out in the last month of the summer.[21] The festival was carried out by the king himself, followed by his wife, royal family, and the court.[21] When the king entered the sanctuary of the god Min, he brought offerings and burning incense.[21] Then, the standing god was carried out of the temple on a shield carried by 22 priests.[21] In front of the statue of the god there were also two small seated statues of the pharaoh. In front of the god Min there was a large ceremonial procession that included dancers and priests. In front of them was a king with a white bull that was wearing a solar disc between its horns.[21] When the god arrived at the end of the procession, he was given sacrificial offerings from the pharaoh. At the end of the festival, the pharaoh was given a bundle of cereal that symbolised fertility.[21]

Building activity and monuments

In contrast to the buildings of other pharaohs, many of the monuments from the reign of Ramesses II are well preserved. There are accounts of his honor hewn on stone, statues, remains of palaces and temples, most notable the Ramesseum in the western Thebes and the rock temples of Abu Simbel. He covered the land from the Delta to Nubia with buildings in a way no king before him had done.[22] He also founded a new capital city in the Delta during his reign called Pi-Ramesses; it had previously served as a summer palace during Seti I's reign.[citation needed]

His memorial temple Ramesseum, was just the beginning of the pharaoh's obsession with building. When he built, he built big, on a scale unlike almost anything before. In the third year of his reign Ramesses started the most ambitious building project after the pyramids, that were built 1500 years earlier. The population was put to work on changing the face of Egypt. In Thebes, the ancient temples were transformed, so that each one of them reflected honour to Ramesses as a symbol of this divine nature and power. Ramesses decided to eternalise himself in stone, so he ordered to change the way and the principle the stone was shaped. Previous pharaohs had carved across the images and words of their predecessors, and the elegant reliefs could have been easely transformed, so Ramesses insisted on a different style where the pictures were instead deeply engraved in stone. They showed and shined more clearly on the Egyptian sun reflecting his relationship with the sungod, Ra. But probably it was more important to him that they were much harder to erase so that any of his successors will not be able to efface him from history.[citation needed]

Ramesses constructed many large monuments, including the archeological complex of Abu Simbel, and the mortuary temple known as the Ramesseum. He built on a monumental scale to ensure that his legacy would survive the ravages of time. It is said[who?] that there are more statues of him in existence than of any other Egyptian pharaoh, since he was the second-longest reigning Pharaoh of Egypt after Pepi II. Ramesses also used art as a means of propaganda for his victories over foreigners and are depicted on numerous temple reliefs. Ramesses II also erected more colossal statues of himself than any other pharaoh. He also usurped many existing statues by inscribing his own cartouche on them. Many of these building projects date from his early years and it appears that there was a considerable economic decline towards the end of his 66-year reign.[citation needed]

- Pi-Ramesses

Here once stood some of the greatest monuments and buildings that Ramesses was building all across Egypt. This city was a jewel in the crown. Although Pi-Ramesses was mentioned and named in the Bible, as a site where the Isralites were forced to work hard for the pharaoh, for many centuries it was lost, considered nothing more than a myth. But after 20 years of excavation, it was finally found in the eastern Delta.[citation needed] Its foundations lie hidden several feet beneath lush farmland. At the site the colossal feet of the statue of Ramesses are almost all that remains above ground today, the rest is buried in the fields. The ancient city was dominated by huge temples, vast residential palace of the king, complete with its own zoo. The city also had a massive chariot base, as described in the Bible.[citation needed]

- Ramesseum

Ever since the 19th century, the temple complex known as the Ramesseum, which was built by Ramesses II between Qurna and the desert, has been known by this name. The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus marveled at his gigantic and famous temple which is now no more than a few ruins.[23]

Oriented northwest and southeast, the temple itself was preceded by two courts. An enormous pylon stood before the first court, with the royal palace at the left and the gigantic statue of the king looming up at the back.[21] Only fragments of the base and torso remain of the syenite statue of the enthroned pharaoh, 17 meters high and weighing more than 1000 tons. The scenes of the great pharaoh and his army triumphing over the Hittite forces fleeing before Kadesh, represented on the pylon.[21] Remains of the second court include part of the internal facade of the pylon and a portion of the Osiride portico on the right.[21] Scenes of war and the rout the Hittites at Kadesh are repeated on the walls.[21] In the upper registers, feast and honor of the phallic god Min, god of fertility.[21]On the opposite side of the court the few Osiride pillars and columns still left can furnish an idea of the original grandeur.[21]

Scattered remains of the two statues of the seated king can also be seen, one in pink granite and the other in black granite, which once flanked the entrance to the temple.[21] Thirty-nine out of the forty-eight columns in the great hypostyle hall (m 41x 31) still stand in the central rows. They are decorated with the usual scenes of the king before various gods.[citation needed] Part of the ceiling decorated with gold stars on a blue ground has also been preserved.[21] The sons and daughters of Ramesses appear in the procession on the few walls left. The sanctuary was composed of three consecutive rooms, with eight columns and the tetrastyle cell.[21] Part of the first room, with the ceiling decorated with astral scenes, and few remains of the second room are all that is left. Vast storerooms built in mud bricks stretched out around the temple.[21] Traces of a school for scribes were found among the ruins.[citation needed]

A temple of Seti I, of which nothing is now left but the foundations, once stood to the right of the hypostyle hall.[citation needed] It consisted of a peristyle court with two chapel shrines. The entire complex was enclosed in mud brick walls which started at the gigantic southeast pylon.[citation needed]

- Abu Simbel

In the year 1255 BC Ramesses and his queen Nefertari had traveled into Nubia to inaugurate a new temple, a wonder of the ancient world, this was the great Abu Simbel. Its an ego cast in stone. The man who built it intended not only to become the Egypt´s greatest pharaoh but also one of its gods.[citation needed]

The great temple of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel was discovered in 1813 by the famous Swiss Orientalist and traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt. However, four years passed before anyone could enter the temple, because an enormous pile of sand almost completely covered the facade and its colossal statues, blocking the entranceway. This feat was achieved by the great Paduan explorer Giovanni Battista Belzoni, who managed to penetrate the interior on 4 August 1817.[24]

- Colossal statue

The colossal statue of Ramesses II was reconstructed and erected in Ramesses Square in Cairo in 1955. In August 2006, contractors moved the 3,200-year-old statue of him from Ramesses Square to save it from exhaust fumes that were causing the 83-ton statue to deteriorate.[25] The statue was originally taken from a temple in Memphis. The new site will be located near the future Grand Egyptian Museum.[citation needed]

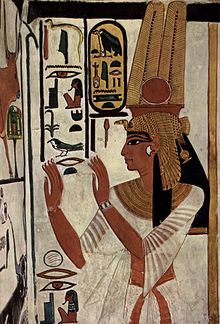

- Tomb of Nefertari

The important and famous consort of Ramesses was discovered by Ernesto Schiaparelli in 1904.[24][21] Although it had been looted in ancient times, the tomb of Nefertari is extremely important, because its magnificent wall painting decoration is surely to be regarded as one of the greatest achievements of ancient Egyptian art.[24] A flight of steps cut out of the rock gives access to the antechamber, which is decorated with paintings based on Chapter 17 of the Book of the Dead.[24] This astronomical ceiling represents the heavens and is painted in dark blue, with a myriad of golden five-pointed stars. The east wall of the antechamber is interrupted by a large opening flanked by representation of Osiris at left and Anubis at right; this in turn leads to the side chamber, decorated with offering scenes, preceded by a vestibule in which the paintings portray Nefertari being presented to the gods who welcome her. On the north wall of the antechamber is the stairway that goes down to the burial chamber.[24] This latter is a vast quadrangular room covering a surface area about 90 square meters, the astronomical ceiling of which is supported by four pillars entirely covered with decoration. Originally, the queen's red granite sarcophagus lay in the middle of this chamber.[24] According to religious doctrines of the time, it was in this chamber, which the ancient Egyptians called the "golden hall" that the regeneration of the deceased took place. This decorative pictogram of the walls in the burial chamber drew inspirations from chapters 144 and 146 of the Book of the Dead: in the left half of the chamber, there are passages from chapter 144 concerning the gates and doors of the kingdom of Osiris, their guardians, and the magic formulas that had to be uttered by the deceased in order to go past the doors.[24]

- Tomb KV5

In 1995, Professor Kent Weeks, head of the Theban Mapping Project rediscovered Tomb KV5. It has proven to be the largest tomb in the Valley of the Kings which originally contained the mummified remains of some of this king's estimated 52 sons. Approximately 150 corridors and tomb chambers have been located in this tomb as of 2006 and the tomb may contain as many as 200 corridors and chambers.[26] It is believed that at least 4 of Ramesses' sons including Meryatum, Sety, Amun-her-khepeshef (Ramesses' first born son) and "the King's Principal Son of His Body, the Generalissimo Ramesses, justified" (ie: deceased) were buried there from inscriptions, ostracas or canopic jars discovered in the tomb.[27] Joyce Tyldesley writes that thus far

- "no intact burials have been discovered and there have been little substantial funeral debris: thousands of potsherds, faience shabti figures, beads, amulets, fragments of Canopic jars, of wooden coffins... but no intact sarcophagi, mummies or mummy cases, suggesting that much of the tomb may have been unused. Those burials which were made in KV5 were thoroughly looted in antiquity, leaving little or no remains."[27]

Death and legacy

By the time of his death, he was suffering from severe dental problems and was plagued by arthritis and hardening of the arteries. When Ramesses finally died, he was about 90 years old, an incredible lifespan in a land where most people died before they were 50.[citation needed] He had outlived many of his wives and children and left great memorials all over Egypt, especially to his beloved first queen Nefertari. The great pharaoh had been called a father of his nation which was now paralyzed and struck with grief.[citation needed] Nine more pharaohs would take the name Ramesses in his honour, but few ever equalled his greatness. Nearly all of his subjects had been born during his reign and thought the world would end without him. In a way they were right. Ramesses II did become the legendary figure he so desperately wanted to be, but this was not enough. New enemies were attacking the empire which also suffered internal problems and it could not last. Less than 150 years after Ramesses died, the Egyptian empire fell, his descendants lost their power and the New Kingdom came to an end.

Mummy

Ramesses II was buried in the Valley of the Kings on the western bank of Thebes in Egypt, in KV7, but his mummy was later moved to the mummy cache at Deir el-Bahri, where it was found in 1881. In 1885, it was placed in Cairo's Egyptian Museum where it remains as of 2008.[citation needed]

The pharaoh's mummy features a hooked nose and strong jaw, and is below average height for an ancient Egyptian, standing some five feet, seven inches.[28] His successor was ultimately to be his thirteenth son: Merneptah.

In 1974, Cairo Museum Egyptologists noticed that the mummy's condition was rapidly deteriorating. They decided to fly Ramesses II's mummy to Paris for examination. Ramesses II was issued an Egyptian passport that listed his occupation as "King (deceased)." According to a Discovery Channel documentary, the mummy was received at a Paris airport with the full military honours befitting a king.[citation needed]

In Paris, Ramesses' mummy was diagnosed and treated for a fungal infection. During the examination, scientific analysis revealed battle wounds and old fractures, as well as the pharaoh's arthritis and poor circulation.

For the last decades of his life, Ramesses II was essentially crippled with arthritis and walked with a hunched back,[29] and a recent study excluded ankylosing spondylitis as a possible cause of the pharaoh's arthritis.[30] A significant hole in the pharaoh's mandible was detected while "an abscess by his teeth was serious enough to have caused death by infection, although this cannot be determined with certainty."[31] Microscopic inspection of the roots of Ramesses II's hair revealed that the king may have been a redhead.[31] After Ramesses' mummy returned to Egypt, it was visited by the late President Anwar Sadat and his wife.

The results of the study were edited by L. Balout, C. Roubet and C. Desroches-Noblecourt, and was titled 'La Momie de Ramsès II: Contribution Scientifique à l'Égyptologie (1985).' Balout and Roubet concluded that "the anthropological study and the microscopic analysis" of the pharaoh's hair showed that Ramses II was "a fair-skinned man related to the Prehistoric and Antiquity Mediterranean peoples, or briefly, of the Berber of Africa."

Pharaoh of the Exodus

At least as early as Eusebius of Caesarea,[citation needed] Ramesses II was identified with the pharaoh of whom the Biblical figure Moses demanded his people be released from slavery.

This identification has often been disputed, though the evidence for another solution is likewise inconclusive as Critics point out that Ramesses II was not drowned in the Sea. Although the Exodus account makes no specific claim that the pharaoh was with his army when they were "swept ... into the sea,"[32] the account in Psalm 136 does claim both Pharaoh and his army were destroyed at the sea.[33]

Critics of the theory also emphasize that there is nothing in the archaeological records from the time of Ramesses' reign to confirm the existence of the Plagues of Egypt. However, this is not surprising since few pharaohs wished to record natural disasters or military defeats in the same manner that their rivals documented these events (as in the Biblical narratives). For instance, after the serious Egyptian military setback at the Battle of Kadesh, Hittite archives uncovered in Boghazkoy reveal that "a humiliated Ramesses [was] forced to retreat from Kadesh in ignominious defeat" and abandon the border provinces of Amurru and Upi to the control of his Hittite rival without the benefit of a formal truce.[34] By contrast, no inconvenient references to Ramesses' loss of Amurru or Upi are preserved in the Egyptian records. Ramesses instead falsely claims that the "Hittite king sent a letter to the Egyptian camp pleading for peace. Negotiators were summoned and a truce was agreed, although Ramesses, still claiming an Egyptian victory...refused to sign a formal treaty. Ramesses [then] returned home to enjoy his personal triumph."[34]

The dates now ascribed to Ramesses' reign by most modern scholars do not match the internal biblical chronology regarding the date of the Exodus, and the now commonplace view is that the Pharaoh mentioned is not Ramesses.[citation needed]

Connection with the Biblical king Shishak

Speculation that Ramesses II was the Biblical Pharaoh named Shishak who attacked Judah and seized war bounty from Jerusalem in Year 5 of Rehoboam is untenable because Ramesses II (and his son Merneptah) retained firm control over Canaan during their reigns. Neither Israel nor Judah could have existed as independent states during this period of Egypt's New Kingdom Empire.[citation needed]

The Shishak of the Bible has generally been associated with Shoshenq I of Egypt instead. A fragment of a stela bearing Shoshenq I's name has been found at Megiddo which affirms this king's claim, in several Karnak temple walls, that he invaded the land of Israel and conquered 170 towns there.[35] Shoshenq's Karnak triumphal inscription goes on to list the towns in alphabetical order including Megiddo. Jerusalem is not seen among this list of towns but the Karnak reliefs are damaged in several sections and some town's names were lost, so many scholars suggest that Jerusalem is mentioned in the damaged part [36].

Popular legacy

He was considered the inspiration for Percy Bysshe Shelley's famous poem Ozymandias. Diodorus Siculus gives an inscription on the base of one of his sculptures as "King of Kings am I, Osymandias. If anyone would know how great I am and where I lie, let him surpass one of my works." [37] This is paraphrased in Shelley's poem.

The life of Ramesses II has inspired a large number of fictional representations, including the historical novels of the French writer Christian Jacq, the Ramsès, series, the graphic novel Watchmen, the character of Adrian Veidt uses Ramesses II to form part of the inspiration for his alter-ego known as 'Ozymandias' and Norman Mailer's novel Ancient Evenings is largely concerned with the life of Ramesses II, though from the perspective of Egyptians living during the reign of Ramesses IX, and Ramesses was the main character in the Anne Rice book The Mummy or Ramses the Damned. Although not a major character, Ramesses appears in Joan Grant's So Moses Was Born, a first person account from Nebunefer, the brother of Ramoses, which paints the picture of the life of Ramoses from the death of Seti, with all the power play, intrigue, plots to assassinate, following relationships are depicted: Bintanath, Queen Tuya, Nefertari, and Moses.

In film, Ramesses was played by Yul Brynner in the classic film The Ten Commandments (1956). Here Ramesses was portrayed as a vengeful tyrant, ever scornful of his father's preference for Moses over "the son of [his] body". The animated film The Prince of Egypt, also featured a depiction of Ramesses (voiced by Ralph Fiennes), portrayed as Moses' adoptive brother.

See also

Notes & references

Notes

- ^ a b c Tyldesly (2001) p. xxiv

- ^ a b Clayton (1994) p. 146

- ^ "Ozymandias". Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ^ a b James Putnan, An introduction to Egyptology, 1990

- ^ Michael Rice, Who's Who in Ancient Egypt, Routledge, 1999

- ^ Jürgen von Beckerath, Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten, Mainz, (1997), pp.108 and 190

- ^ Peter J. Brand, The Monuments of Seti I: Epigraphic, Historical and Art Historical Analysis, Brill, NV Leiden (2000), pp.302-305

- ^ David O'Connor & Eric Cline, Amenhotep III: Perspectives on his reign, University of Michigan Press, 1998, p.16

- ^ Dodson & Hilton (2004), p.164

- ^ Dodson & Hilton (2004) p.160

- ^ Dodson & Hilton (2004) pp.170-172

- ^ Dodson & Hilton (2004) p.166

- ^ Dodson & Hilton (2004) p.173

- ^ Grimal (1992) pp.250-253

- ^ Tyldesley (2000), pp.53

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas, A History of Ancient Egypt (1994) pp. 253ff.

- ^ Grimal, op. cit., p.257

- ^ Geoff Edwards. "Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham". Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ^ "Sed festival". The Global Egyptian Museum. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ^ "Min".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Skliar (2005)

- ^ Wolfhart Westendorf, Das alte Ägypten, 1969

- ^ Diodorus Siculus. The Historical Library of Diodorus the Sicilian. pp. Ch.11, p.33.

- ^ a b c d e f g Alberto Siliotti, Egypt: temples, people, gods,1994

- ^ BBC NEWS | Middle East | Giant Ramses statue gets new home

- ^ Tomb of Ramses II sons

- ^ a b Tyldesley, Ramesses, p.161-162

- ^ Tyldesley, Ramesses p. 14

- ^ Bob Brier, The Encyclopedia of Mummies, Checkmark Books, 1998., p.153

- ^ Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2004 Oct;55(4):211-7, PMID 15362343

- ^ a b Brier, op. cit., p.153

- ^ Exodus 14

- ^ book_id=23&chapter=136&verse=15&version=9&context=verse Psalm 136:15

- ^ a b Tyldesley, Ramesses, p.73

- ^ K. A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William Erdsman & Co, 2003. pp.10, 32-34 & 607

- ^ The Epigraphic Survey, Reliefs and Inscriptions at Karnak III: The Bubastite Portal, Oriental Institute Publications, vol. 74 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1954)

- ^ RPO Editors. "Percy Bysshe Shelley : Ozymandias". University of Toronto Department of English. University of Toronto Libraries, University of Toronto Press. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)

Bibliography

- Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson (2004)

- James Putnan, An introduction to Egyptology, 1990

- Von Beckerath, Jürgen. 1997. Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten, Mainz, Philipp von Zabern.

- Peter J. Brand, The Monuments of Seti I: Epigraphic, Historical and Art Historical Analysis, Brill, NV Leiden (2000)

- David O'Connor & Eric Cline, Amenhotep III: Perspectives on his reign, University of Michigan Press, 1998

- Tyldesley, Joyce. 2000. Ramesses: Egypt's Greatest Pharaoh. London: Viking/Penguin Books

- N. Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992)

- Ania Skliar, Grosse kulturen der welt-Ägypten, 2005

- Wolfhart Westendorf, Das alte Ägypten, 1969

- Michael Rice, Who's Who in Ancient Egypt, Routledge, 1999

- Alberto Siliotti, Egypt: temples, people, gods, 1994

- Bob Brier, The Encyclopedia of Mummies, Checkmark Books, 1998

- Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2004 Oct;55(4):211-7, PMID 15362343

- The Epigraphic Survey, Reliefs and Inscriptions at Karnak III: The Bubastite Portal, Oriental Institute Publications, vol. 74 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1954)

- RPO Editors. "Percy Bysshe Shelley : Ozymandias". University of Toronto Department of English. University of Toronto Libraries, University of Toronto Press. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)

Further reading

- Hasel, Michael G. 1994. “Israel in the Merneptah Stela,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 296., pp. 45-61.

- Hasel, Michael G. 1998. Domination and Resistance: Egyptian Military Activity in the Southern Levant, 1300–1185 BC. Probleme der Ägyptologie 11. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10984-6

- Hasel, Michael G. 2003. "Merenptah's Inscription and Reliefs and the Origin of Israel" in Beth Alpert Nakhai ed. The Near East in the Southwest: Essays in Honor of William G. Dever, pp. 19–44. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 58. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research. ISBN 0-89757-065-0

- Hasel, Michael G. 2004. "The Structure of the Final Hymnic-Poetic Unit on the Merenptah Stela." Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 116:75–81.

- James, T. G. H. 2000. Ramesses II. New York: Friedman/Fairfax Publishers. A large-format volume by the former Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, filled with colour illustrations of buildings, art, etc. related to Ramesses II

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. 1982. Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II, King of Egypt. Monumenta Hannah Sheen Dedicata 2. Mississauga: Benben Publications. ISBN 0-85668-215-2. This is an English language treatment of the life of Ramesses II at a semi-popular level

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. 1996. Ramesside Inscriptions Translated and Annotated: Translations. Volume 2: Ramesses II; Royal Inscriptions. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-18427-9. Translations and (in the 1999 volume below) notes on all contemporary royal inscriptions naming the king.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. 1999. Ramesside Inscriptions Translated and Annotated: Notes and Comments. Volume 2: Ramesses II; Royal Inscriptions. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. 2003. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, ISBN 0-8028-4960-1.

External links

- YouTube video about Ramesses the Great and Egyptian empire

- Ramesses II - Archaeowiki.org

- Ramesses the Great

- BBC history: Ramesses the Great

- King Ramses II

- 19th DYNASTY

- Egypt's Golden Empire: Ramesses II

- Usermaatresetepenre

- RAMESSES THE GREAT

- Ramesses II Usermaatre-setepenre (about 1279-1213 BC)

- The TOMB of RAMESSES II and REMAINS of HIS FUNERARY TREASURE

- THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART: Relief of a King, probably Ramesses II

- Mortuary temple of Ramesses II at Abydos

- Ramesseum

- Ram·e·ses II

- Egyptian monuments: Temple of Ramesses II

- Ramesses II at Find a Grave

- List of Ramesses II's family members and state officials

- Temples from the time of Ramesses the Great

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA