History of Alaska

While the documentary history of Alaska dates from European settlement, the present State of Alaska was probably first settled by humans who came there across the Bering Land Bridge. It is probable that all pre-Columbian peoples of the Americas crossed the land bridge before migrating. At the time of European contact by the Russian explorers, the area was populated by the Eskimos and a variety of Native American groups. In 1741, Vitus Bering (navigator in the service of the Russian Navy) brought back what were judged to be the finest otter furs in the world. The Russian-American Company soon began hunting the otters and helping to colonize much of coastal Alaska, but shipping costs meant that the colony was never very profitable.

Because of financial difficulties in Russia, the desire to keep Alaska out of British hands, and the low profits of trade with Alaskan settlements, Russia was willing to sell its possessions in North America. U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward engineered the Alaskan purchase on April 9, 1867 for US$7.2 million (approximately US$90 million in 2005 dollars). The nearby Yukon Territory in Canada and Alaska itself were the site of a gold rush in the 19th century, and they remained a significant source of mining even after the gold reserves diminished. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Alaska Statehood Act into law on July 7, 1958 which paved the way for Alaska's admission into the Union as the 49th State on January 3, 1959.

Prior to the discovery of oil and the building of the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline, Alaska was primarily a wilderness state. The area suffered one of the worst earthquakes in recorded North American history on March 27, 1964, the "Good Friday Earthquake," which killed 103 people and leveled several villages, though oil revenues helped reestablish the population and infrastructure of the state. In 1989, the Exxon Valdez hit a reef in the Prince William Sound, spilling between 11 and 35 million gallons (42–132 million liters) of crude oil over 1,100 miles (1,600 km) of coastline. The fates of the large reserves of wild frontier in the state are under debate, as the highly political debate over the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge shows.

Prehistory

For additional details see the main article Prehistory of Alaska.

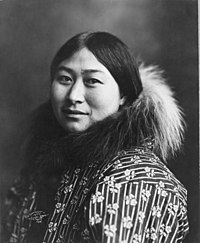

Paleolithic families moved into northwestern North America sometime between 16,000 and 10,000 BCE across the Bering Land Bridge in western Alaska. They found their passage blocked by a huge sheet of ice until a temporary recession in the last ice age that opened up an ice-free corridor through northwestern Canada, allowing bands to fan out throughout the rest of the continent. Eventually, Alaska became populated by the Inuit and a variety of Native American groups. Today, early Alaskans are divided into several main groups: the Southeastern Coastal Indians (the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian), the Athabascans, the Aleut, and the two groups of Eskimos, Inupiat and Yup'ik [1].

The Tlingit, Haida, and Athabascans would hold potlachs in which the a person in a position of power would give away all of his possessions, have them eaten, or destroyed. At these potlachs, family histories would be recited, ceremonial titles would be transfered, and offerings would be given to ancestors. The Aleut society was divided into three categories: honorables, comprising the respected whalers and elders; common people; and slaves. At death, the body of an honorable was mummified, and slaves were occasionally killed in honor of the deceased. Means of hunting for these groups included snares, clubs, spears, and bows and arrows. [2]

Russian Alaska

The first written accounts indicate that the first Europeans to reach Alaska came from Russia. One legend holds that a Russian settlement was established as early as 1648, when Semyon Dezhnev, a Siberian explorer, and Fedot Alekseev, a Russian merchant, began exploring the region, though there is little existing evidence to back this claim up. In June 1741, the St. Peter, captained by a Dane, Vitus Bering, and the St. Paul, captained by a Russian, Alexei Chirikov, set sail from Russia at the Siberian port of Petropavlovsk [3]. Georg Wilhelm Steller, the ship's naturalist, hiked along the island and took notes on the plants and wildlife.

After surviving a shipwreck, Bering's crew returned to Russia with sea otter pelts, soon judged to be the finest fur in the world. Russia soon threw itself into creating hunting and trading posts. Catherine the Great, who became Czarina in 1763, proclaimed good will toward the Aleuts and urged her subjects to treat them fairly, but the hunters' quest for furs made them disregard Aleut welfare. In 1784, Grigory Ivanovich Shelikhov, who would later set up the Russian-Alaska Company that colonized early Alaska, arrived in Three Saints Bay on Kodiak Island with two ships, the Three Saints and the St. Simon [4]. The indigenous Koniag harassed the Russian party and Shelikhov responded by killing hundreds and taking hostages to enforce the obedience of the rest. Having established his authority on Kodiak Island, Shelikhov founded the first permanent Russian settlement in Alaska on the island's Three Saints Bay, built a school to teach the natives to read and write Russian, and introduced the Russian Orthodox religion.

In 1790, Shelikhov, back in Russia, hired Alexandr Baranov to manage his Alaskan fur enterprise. n 1795, Baranov, concerned by the sight of non-Russian Europeans trading with the Natives in southeast Alaska, established Mikhailovsk six miles (10 km) north of present-day Sitka. By 1804, Alexandr Baranov, now manager of the Russian–American Company, had consolidated the company's hold on fur trade activities in the Americas. However, profits began to fall due to overhunting and dependence on American supply ships. Rather than let the British have the region, Russian America was sold to the U.S., all the holdings of the Russian–American Company were liquidated.

Spain's attempts at colonization

Out of fears of Russian expansion, King Charles III of Spain sent forth from Mexico a number of expeditions to explore the Pacific Northwest between 1774 and 1791 . The second expedition, led by Lieutenant Bruno de Hezeta aboard the Santiago, along with 90 men set sail from San Blas on March 16, 1775 with orders to claim the Pacific Northwest for Spain. Accompanying Hezeta was the escort and supply ship Nuestra Sonora de Guadalupe (generally known as the Sonora), initially under the command of Juan Manuel de Ayala. The 37 foot (13.5 meter) schooner and its crew complement of 16 were to perform coastal reconnaissance and mapping, and could make landfall in places the larger Santiago was unable to approach on its previous voyage; in this way, the expedition could officially lay claim to the lands north of Mexico it visited.

The two ships sailed together as far north as Point Grenville, Washington, named Punta de los Martires (or "Point of the Martyrs") by Hezeta in response to an attack by the local Quinault Indians. By design, the vessels parted company on the evening of July 29, 1775 with the Santiago continuing to what is today the border between Washington state and Canada. The Sonora (now with second officer Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra at the helm) moved up the coast according to its orders, ultimately reaching a position at Latitude 59° North on August 15, entering Sitka Sound near the present-day town of Sitka, Alaska. It is there that the Spaniards performed numerous "acts of sovereignty," naming and claiming Puerto de Bucareli (Bucareli Sound), Puerto de los Remedios, and Mount San Jacinto, renamed Mount Edgecumbe by British explorer James Cook three years later.

Throughout the voyage the crews of both vessels endured many hardships, including food shortages and scurvy. On September 8, the ships rejoined and headed south for the return trip to San Blas. In the end, the North Pacific rivalry proved to be too costly for Spain, who withdrew from the contest and abandoned its claims to the region in 1819. Today, Spain's Alaskan legacy endures as little more than a few place names, among these the Malaspina Glacier and the town of Valdez.

Britain's presence

British settlements in Alaska consisted of a few scattered trading outposts. Captain James Cook, midway through his third and final voyage of exploration in 1778, sailed along the west coast of North America aboard the HMS Resolution, mapping the coast from California all the way to the Bering Strait. During the trip, he discovered what came to be known as Cook Inlet (named in honor of Cook in 1794 by George Vancouver, who had served under his command) in Alaska. The Bering Strait proved to be impassable, although the Resolution and its companion ship HMS Discovery made several attempts to sail through it. The ships left the straits to return to Hawaii in 1779.

During Cook's visit while searching for the Northwest Passage, the Russians tried to impress him with the extent of their control over the region, but Cook considered them a tenuous group of ragtag hunters and traders. Although Cook died in Hawaii after visiting Alaska, his crew continued on to Canton in China, where they sold sea otter pelts they had bought at Alaska for relatively high prices. Cook's expedition spurred the British to increase their sailings along the northwest coast, following in the wake of the Spanish. Three Alaska-based posts, funded by the Hudson's Bay Company, operated at Fort Yukon, on the Stikine River, and in Wrangell (the only Alaskan town to have been the subject of British, Russian, and American rule) throughout the early 1800s.

The Department of Alaska

At the instigation of U.S. Secretary of State William Seward, the United States Senate approved the purchase of Alaska from Russia for $7,200,000 (approximately $90,750,000 in 2005 dollars, adjusted for inflation) on 9 April 1867, and the United States flag was raised on 18 October of that same year (now called Alaska Day). Coincident with the ownership change, the de facto International Date Line was moved westward, and Alaska changed from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar. Therefore, for residents, Friday, October 6, 1867 was followed by Friday, October 18, 1867; two Fridays in a row because of the date line shift.

During the Department era, Alaska was variously under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army (until 1877), the United States Department of the Treasury (from 1877 until 1879) and the U.S. Navy (from 1879 until 1884). The area later became the Alaska Territory, then Alaska. When Alaska was first bought, the vast majority remained unexplored. In 1865, Western Union laid a telegraph line across Alaska to Bering Strait where it would connect with an Asian line. It also conducted the first scientific studies of the region and produced the first map of the entire Yukon River. The Alaska Commercial Company and the military also contributed to the growing exploration of Alaska in the last decades of the 1800s, building trading posts along the Interior's many rivers.

District of Alaska

For additional details see the main article District of Alaska.

In 1884 the region was organized and the name was changed from the Department of Alaska to the District of Alaska. At the time, legislators in Washington, D.C., were occupied with post-Civil War reconstruction issues, and had little time to dedicate to Alaska. In 1896, the discovery of gold in Yukon Territory brought thousands of miners to Alaska, and though it was uncertain if gold was to be found in Alaska at the time, Alaska majorly profited because it was along the easiest transportation route.

In 1899, gold was found in Alaska itself in Nome, and several towns subsequently began to be built, including Valdez and Fairbanks. In 1902 the Alaska Railroad began to be built, which would connect from Seward to Fairbanks by 1914, though Alaska still doesn't have a railroad connecting it to the lower 48 states today. Still, an overland route was built, cutting off transportation to the contiguous states by days. The industries of copper mining, fishing, and canning began to become popular in the early 1900s, with 10 canneries in some major towns.

Alaska Territory

By the turn of the 20th century, commercial fishing was gaining a foothold in the Aleutian Islands. Packing houses salted cod and herring, and salmon canneries were opened. Another traditional occupation, whaling, continued with no regard for overhunting. They pushed the bowhead whales to the edge of extinction for the oil in their tissue, but in recent years their populations have rebounded enough, due to a decline in commercial whaling, for Natives to harvest many each year without affecting the population. The Aleuts soon suffered severe problems due to the depletion of the fur seals and sea otters which they needed for survival. As well as requiring the flesh for food, they also used the skins to cover their boats, without which they could not hunt. The Americans also expanded into the Interior and Arctic Alaska, exploiting the furbearers, fish, and other game on which Natives depended.

In 1912, Alaska was reorganized and renamed the Territory of Alaska when Congress passed the Second Organic Act [5]. By 1916, its population was about 58,000. James Wickersham, a Delegate to Congress, introduced Alaska's first statehood bill, but it failed to due lack of interest from Alaskans. Even President Harding's visit in 1923 could not create widespread interest in statehood. Under the conditions of the Second Organic Act, Alaska had been split into four divisions. The most populous of the divisions, whose capital was Juneau, wondered if it could become a separate state from the other three. Government control was a primary concern, with the territory having 52 federal agencies.

Then, in 1920 the Jones Act required U.S.-flagged vessels to be built in the United States, owned by U.S. citizens, and documented under the laws of the United States. All goods entering or leaving Alaska had to be transported by American carriers and shipped to Seattle, making Alaska dependent on Washington. The Supreme Court ruled that the provision of the Constitution saying one state shouldn't hold sway over another's commerce did not apply because Alaska was only a territory. The prices Seattle shipping businesses charged began to rise to take advantage of the situation.

The Depression in Alaska caused prices of fish and copper, vital to Alaska's economy at the time, to decline. Wages were dropped and the workforce decreased by more than half. In 1935, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt thought Americans from agricultural areas could be transferred to Alaska's Matanuska-Susitna Valley for a fresh chance at agricultural self-sustainment. Colonists were largely from northern states such as Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota under the belief that only those who grew up with climates similar to that of Alaska's could handle settler life there. The United Congo Improvement Association asked the president settle 400 African-American farmers in Alaska, saying that the territory would offer full political rights, but racial prejudice and the belief that only those from northern states would make suitable colonists caused the proposal to fail.

World War II

For additional details see the main article Battle of the Aleutian Islands.

During World War II, the three of the outer Aleutian Islands—Attu, Agattu and Kiska—were the only part of the United States to have land occupied during the war. The Japanese launched the campaign mostly as a distraction to battles taking place in other parts of the world, but also intended to use the islands as a base for launching a campaign against the contiguous U.S. The battle became a matter of national pride, defending the nation against the first foreign military campaign on U.S. soil since the War of 1812.

On June 3, 1942 the Japanese launched an air attack on Dutch Harbor, a U.S. naval base on Unalaska Island [6]. U.S. forces managed to hold off the planes, and the base survived this attack, and a second one, with minor damage. On June 7, the Japanese landed on the islands of Kiska and Attu, where they overwhelmed Attu villagers. The villagers were taken to Japan and interned for the remainder of the war. Aleuts from the Pribilofs and Aleutian villages were evacuated by the United States to Southeast Alaska.

In the fall of 1942, the U.S. Navy began constructing a base on Adak, and on May 11 1943, American troops landed on Attu, determined to retake the island [7]. The battle wore on for more than two weeks. The Japanese, who had no hope of rescue because their fleet of transport submarines had been turned back by U.S. destroyers, fought to the last man. The end finally came on May 29 when the Americans repelled a banzai charge. Some Japanese remained in hiding on the small island for up to three months after their defeat. When discovered, they killed themselves rather than surrender. There were 3929 American casualties; 549 were killed, 1148 were injured, 1200 had severe cold injuries, 614 succumbed to disease, and 318 died of miscellaneous causes, largely Japanese booby traps and friendly fire.

The U.S. then turned its attention to the other occupied island, Kiska. From June through August, tons of bombs were dropped on the tiny island. The Japanese, under cover of thick Aleutian fog, escaped via transport ships. After the war, the Native Attuans who had survived internment in Japan were resettled to Atka by the federal government, which considered their home villages too remote to defend.

As a result of World War II, the construction of the Alaska–Canada Military Highway was completed in 1942 to form an overland supply route to America's Russian allies on the other side of the Bering Strait. Running from Great Falls, Montana, to Fairbanks, the road was the first stable link between Alaska and the rest of America. The construction of military bases also contributed to the population growth of some Alaskan cities. Anchorage almost doubled in size, from 4,200 people in 1940 to 8,000 in 1945.

Statehood

By the turn of the 20th century, a movement pushing for Alaska statehood began, but in the contiguous 48 states, legislators were worried that Alaska's population was too sparse, distant, and isolated, and its economy was too unstable for it to be a worthwhile addition to the United States [8]. World War II and the Japanese invasion highlighted Alaska's strategic importance, and the issue of statehood was taken more seriously, but it was the discovery of oil at Swanson River on the Kenai Peninsula that dispelled the image of Alaska as a weak, dependent region. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Alaska Statehood Act into United States law on 7 July 1958, which paved the way for Alaska's admission into the Union on January 3, 1959. Juneau, the territorial capital, continued as state capital, and William A. Egan was sworn in as the first governor.

Alaska has no counties in the sense used in the rest of the country. Instead, the state is divided into 27 census areas and boroughs. The difference between boroughs and census areas is that boroughs have an organized area-wide government, while census areas are artificial divisions defined by the United States Census Bureau for statistical purposes only. Areas of the state not in organized boroughs compose what the government of Alaska calls the "unorganized borough". Borough-level government services in the "unorganized borough" are provided by the state itself.

The "Good Friday Earthquake"

For additional details see the main article Good Friday Earthquake.

On March 27, 1964 the "Good Friday Earthquake" struck South-central Alaska, churning the earth for four minutes. The earthquake was one of the most powerful ones ever recorded and killed 131 people [9]. Most of them were drowned by the tsunamis that tore apart the towns of Valdez and Chenega. Throughout the Prince William Sound region towns and ports were destroyed and land was uplifted or shoved downward. The uplift destroyed salmon streams, as the fish could no longer negotiate waterfalls and other barriers to reach their spawning grounds. Ports at Valdez and Cordova were beyond repair, and the fires destroyed what the mud slides hadn't. At Valdez, an Alaska Steamship Company ship was lifted by a huge wave over the docks and out to sea, but most hands survived. At Turnagain Arm, off Cook Inlet, the incoming water destroyed trees and caused cabins to sink into the mud. On Kodiak, a tidal wave wiped out the villages of Afognak, Old Harbor, and Kaguyak and damaged other communities, while Seward lost its harbor.

Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act

Despite the extent of the catastrophe, Alaskans rebuilt many of the communities. In the mid-1960s Alaska Natives had begun participating in the state and local government. More than 200 years after the arrival of the first Europeans, Natives from all ethnic groups united to claim title to lands wrested from them. The government responded slowly, until, in 1968, the Atlantic-Richfield Company discovered oil at Prudhoe Bay on the Arctic coast, and catapulted the issue of land ownership into headlines. In order to lessen the difficulty of drilling at such a remote location and transporting the oil to the lower 48 states, the best solution seemed to be building a pipeline to carry the oil across Alaska to the port of Valdez, built on the ruins of the previous town. At Valdez the oil would be loaded onto tanker ships and sent by water to the contiguous states. The plan was approved, but a permit to construct the pipeline, which would cross lands involved in the native dispute, could not be granted until the Native claims had been settled.

With major petroleum dollars on the line, there was a new urgency for an agreement, and in 1971 the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was signed, under which the Natives relinquished aboriginal claims to their lands [10]. In return they received access to 44 million acres of land and were paid $963 million. The land and money were divided among regional, urban, and village corporations. Some handled their funds wisely and others did not, leaving some Natives land rich and cash poor. The settlement compensated the Natives for the invasion of their lands and also opened the way for all Alaskans to profit from the state's largest natural resource, oil.

The Trans-Alaskan Pipeline

For additional details see the main article Trans-Alaskan Pipeline.

Between Arctic Alaska and Valdez, there were three mountain ranges, active fault lines, miles of unstable, boggy ground underlain with frost, and migration paths of caribou and moose. To counteract the unstable ground and animal crossings, half the 800-mile (approximately 1,300km) pipeline is elevated on supports high enough to keep it from melting the permafrost and destroying natural terrain [11]. To help the pipeline survive an earthquake, it was laid out in a zigzag pattern, so that it would roll with the earth instead of breaking up. The first oil arrived at Valdez on July 28, 1977. The total cost of the pipeline and related projects, including the tanker terminal at Valdez, 12 pumping stations, and the Yukon River Bridge, was $8 billion.

As the oil bonanza took shape, per capita incomes rose throughout the state, with virtually every community benefiting. State leaders were determined that this boom would not end like the fur and gold booms, in an economic bust as soon as the resource had disappeared. In 1976, the people of Alaska amended the state's constitution, establishing the Alaska Permanent Fund. The fund invests a portion of the state's mineral revenue, including revenue from the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline System, "to benefit all generations of Alaskans". Of all mineral lease proceeds, 25% goes into the fund, and income from the fund is divided three ways. It pays annual dividends to all residents who apply and qualify, it adds money to the principal account to hedge against inflation, and it provides funds for state legislature use. The fund is the largest pool of money in the United States and a top lender to the government. Since 1993, the fund has produced more money than the Prudhoe Bay oil fields, whose production is diminishing and may dry up early in the 21st century, though the funds should continue to benefit the state. In March 2005, the fund's value was over $30 billion.

Contemporary Alaska

Prior to 1983, the state lay across four different time zones, Pacific Standard Time (UTC -8 hours) in the extreme southeast, a small area of Yukon Standard Time (UTC -9 hours) around Juneau, Hawaii Standard Time (UTC -10 hours) in the Anchorage and Fairbanks vicinity, with the Nome area and most of the Aleutian Islands observing Bering Standard Time (UTC -11 hours) [12]. In 1983 the number of time zones was reduced to two, with the entire mainland plus the inner Aleutian Islands going to UTC -9 hours (and this zone then being renamed Alaska Standard Time as the Yukon Territory had several years earlier (circa 1975) adopted a single time zone identical to Pacific Standard Time), and the remaining Aleutian Islands were slotted into the UTC −10 hours zone, which was then renamed Hawaii–Aleutian Standard Time.

In the second half of the 20th century, Alaska discovered tourism as an important source of revenue. Tourism became popular after World War II, when men stationed in the region returned home praising its natural splendor. The Alcan Highway, built during the war, and the Alaska Marine Highway System, completed in 1963, made the state more accessible than before. Tourism is now big business in Alaska, and over 1.4 million people visit the state every year, attracted to Denali National Parkm Katmai, Glacier Bay, and the Kenai Peninsula, and although wildlife watching is popular, only a small portion of visitors go to the wilderness.

With tourism more vital to the economy, environmentalism has also risen in importance. Alaskans are trying to balance the needs of their land with those of its residents. Much is already well-protected. The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) of 1980 added 53.7 million acres to the national wildlife refuge system, parts of 25 rivers to the national wild and scenic rivers system, 3.3 million acres to national forest lands, and 43.6 million acres to national park land. As a result of the lands act, Alaska now contains two-thirds of all American national parklands.

On March 24, 1989, the tanker Exxon Valdez ran aground in Prince William Sound, releasing 11 million gallons of crude oil into the water, spreading along 1,100 miles (1,800 km) of shoreline [13]. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, at least 300,000 sea birds, 2,000 otters, and other marine animals died as a result of the spill. Exxon spent US$2 billion on cleaning up in the first year alone. Approximately 12,000 workers went to the shores of the sound in the summer of 1989. Work included bulldozing blackened beaches, sucking up petroleum blobs with vacuum devices, blasting sand with hot water, polishing rocks by hand, raking up oily seaweed, and spraying fertilizer to aid the growth of oil-eating microbes.

The spill generated international publicity, and the influx of cleanup workers filled to capacity every hotel and campsite in the Valdez area, which boosted Valdez's economy, but weakened the tourist industry. Exxon, working with state and federal agencies, continued its cleanup into the early 1990s. In some areas, such as Smith Island, winter storms did more to wash the shore clean than any human efforts. Government studies show that the oil and the cleaning process itself did long-term harm to the ecology of the Sound, interfering with the reproduction of birds and animals in ways that still aren't fully understood. Prince William Sound seems to have recuperated, but scientists still dispute the extent of the recovery.

In a civil settlement, Exxon agreed to pay $900 million in ten annual payments, plus an additional $100 million for newly discovered damages. The Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers Union, representing approximately 40,000 workers nationwide, announced opposition to drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) until Congress enacted a comprehensive national energy policy. In the aftermath of the spill, Alaska governor Steve Cowper issued an executive order requiring two tugboats to escort every loaded tanker from Valdez out through Prince William Sound to Hinchinbrook Entrance. As the plan evolved in the 1990s, one of the two routine tugboats was replaced with a 210-foot Escort Response Vehicle (ERV). The majority of tankers at Valdez are still single-hulled, but Congress has enacted legislation requiring all tankers to be double-hulled by 2015.

Two years after the Exxon Valdez oil spill, President George H.W. Bush's National Energy Bill authorized drilling in ANWR, but a filibuster by Senate Democrats kept the measure from coming to a vote. In 1995, Republicans prepared to take up the battle again and included a provision for ANWR in the federal budget. President Bill Clinton vetoed the entire budget and expressed his intention to veto any other bill that would open ANWR to drilling. Supporters of the drilling claimed there were 16 billion barrels of oil to be recovered, but this number was at the extreme high side of the 1998 U.S. Geological Survey report and represented only a 5% probability of technically recoverable oil across the entire assessment area. Opponents of drilling claimed there were only 3 billion barrels of oil to be recovered, which was at the extreme low end and rounded downward from 3.4 billion barrels. It represented a 95% probability of technically recoverable oil only on federal lands and only the part of ANWR's section 1002 lands nearest the Canning River.

The main point of the USGS report was that there was more oil than previously thought in ANWR and it was heavily concentrated in the western part of Section 1002. In 1998, the average West Coast price for Alaska crude oil was $12.54 per barrel and by September 2000 it had climbed to $37.22. Clinton ordered a release from the nation's Strategic Petroleum Reserve. Democratic candidate Al Gore drew a firm line at the Canning River and former oil men George W. Bush and Dick Cheney were equally adamant in their support for drilling on 1002 lands. In December 2000, a Coast Guard report charged Alyeska with repeated safety violations at a Valdez terminal, causing prices to jump again. In mid-2000, the House of Representatives voted to allow drilling, but in April 2002, the Senate rejected it. The House plans to revote on the issue in March 2005. The Senate already passed funding for drilling provisions on March 16th, 2005 as part of the budget for fiscal year 2006.

Today, Alaska is one of the only states never to have had a death penalty, although it did execute eight men between 1900 and 1957 under civil authority. In 1957, the death penalty was abolished by the Territorial Legislature, just two years before Alaska's statehood.

References

Book references:

-

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - . ISBN 0060503068.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 0-919642-53-5.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 0295982497.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 0-8061-2099-1.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 0-930931-15-7.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 094410908X.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help)

Video references:

- (2004). Alaska: Big America [TV documentary]. The History Channel: AAE-44069.

Other references:

- ^ Template:Web reference simple

- ^ (2003). Alaska. Maspeth, NY: Langensheidt Publishers, Inc. ISBN 1-58573-284-2

- ^ Template:Web reference simple

- ^ Template:Web reference simple

- ^ Template:Web reference simple

- ^ Template:Web reference simple

- ^ Template:Web reference simple

- ^ Littke, Peter. (2003). Russian-American Bibliography

- ^ Template:Web reference simple

- ^ Template:Web reference simple

- ^ Template:Web reference simple

- ^ Template:Web reference simple

- ^ Template:Web reference simple