James Bond

James Bond, also known as 007 (pronounced "double-oh seven"), is a fictional British spy introduced by writer Ian Fleming in 1953. Fleming wrote numerous novels and short stories based upon the character and, after his death in 1964, further literary adventures were written by Kingsley Amis, John Pearson, John Gardner, Raymond Benson, and Charlie Higson; in addition, Christopher Wood wrote two screenplay novelizations and other authors have also written various unofficial permutations of the character.

James Bond is best known from the EON Productions film series. Twenty official and two unofficial films have been made featuring this character. Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman produced most of the official films up until 1974 when Broccoli became the sole producer. His daughter, Barbara Broccoli, and his stepson, Michael G. Wilson, carried on the production duties beginning in 1995.

To date, Bond has been portrayed in the official series by:

The 21st official film, Casino Royale, is in pre-production and is slated for a 2006 release. Brosnan has announced that he will not play Bond in this film and the announcement of a new actor is expected sometime in the fall of 2005.

Broccoli's family company, Danjaq, L.L.C., has co-owned the James Bond film series with United Artists Corporation since the mid-1970s, when Saltzman sold UA his share of Danjaq. Currently, the Comcast/Sony consortium distributes the series through United Artists' parent, the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer company.

Two other James Bond films were made independent from EON: the comedy Casino Royale starring David Niven (1967), and Never Say Never Again, a remake of Thunderball starring Sean Connery (1983). An American television adaptation of Fleming's first novel, Casino Royale also aired in 1954 starring Barry Nelson.

In addition to novels and films, Bond is a prominent character in many computer and video games, comic strips and comic books and has been the subject of many parodies.

Overview

The character

Commander James Bond is a member of MI6, the international arm of the British Secret Service, under which he holds the code number "007". The 'double-oh' prefix indicates his discretionary licence to kill in the performance of his duties.

Fleming named James Bond after an ornithologist of the same name who had written A Field Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Fleming, a keen birdwatcher, was in Jamaica with a copy of Bond's field guide when he chose Bond's name for the lead character of his first novel, Casino Royale in 1953. He later explained that the man's name was "brief, unromantic, Anglo-Saxon, and yet very masculine… just what I needed."

The look of James Bond is famed for being "suave and sophisticated." In Casino Royale the character Vesper Lynd says of Bond, "He reminds me rather of Hoagy Carmichael, but there is something cold and ruthless." Carmichael would later be the basis as James Bond for artist Mike Grell and his series of James Bond comic books, while the Hoagy Carmichael description would be repeated in later Bond stories written by John Gardner.

Fleming drew inspiration for the Bond character from his personal life. The author was known for his glamorous and licentious lifestyle. Fleming was also inspired by his contemporaries in British Intelligence during World War II, specifically events that were purported to have taken place at the Estoril Casino in Estoril, Portugal where spies of warring regimes mingled with European royalty. The atmosphere inspired Fleming's imagination and set the scene for his first Bond novel, Casino Royale. (See Inspirations for James Bond.)

Bond is the consummate womaniser, drinker, and smoker. According to a website detailing Bond’s drinking habits, the agent consumed 102 alcoholic beverages in the films, and well over 300 in Fleming's novels. On film, Bond drinks champagne 32 times, and 20 vodka martinis. In the novels, he has a strong preference for bourbon whiskey.

The literary 007 is a heavy cigarette smoker, at one point smoking up to 70 a day. Bond quit smoking when John Gardner authored the stories in the 1980s. On film, Bond gave up the habit in Tomorrow Never Dies, although he is seen smoking cigars in Live and Let Die and Die Another Day.

The cinematic Bond had the character quirk of being a "know-it-all". In Goldfinger, he calculates in his head how many trucks it takes to transport all the gold in Fort Knox, and how long the gold would be radioactive after Goldfinger's bomb had exploded. Bond's "genius" became a running joke during Moore's era. It was virtually eliminated during Dalton's tenure as 007.

The franchise

The Bond franchise is currently the second all-time highest grossing film franchise in history, after Star Wars[1]. James Bond novels and movies have ranged from realistic spy drama to science fiction.

The original books by Fleming are usually dark – lacking fantasy or gadgets. Instead, they established the formula of unique villains, outlandish plots, and voluptuous women who tend to fall in love with Bond at first sight (the feeling often being mutual). The films expanded on Fleming's books, adding gadgets from Q-Branch, and death-defying stunts, and often abandoning the original plotlines for more outlandish and cinema-friendly adventures. Cinematic Bond adventures are mostly a formulaic drama where Bond saves the world from apocalyptic madmen. Inevitably, a villain tries to kill Bond with a deathtrap during which the villain reveals vital information; Bond later escapes and uses the information to thwart the evil plot. In many cases, the villain then dies at Bond's hands, although early Bond films often ended with the villain either escaping or being killed by someone else.

The first actor to play Bond was American Barry Nelson, in the 1954 CBS television production of Casino Royale in which the character became a U.S. agent named "Jimmy Bond." In 1956, Bob Holness provided the voice of Bond in a South African radio adaptation of Moonraker.

Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman started the official cinematic run of Bond in 1962, with Dr. No starring Sean Connery. Their production company, EON Productions (supposedly an acronym for 'Everything Or Nothing', which was their motto), set up a semi-regular schedule of releases (initially annually, then usually once every two years) until 1989. Every Bond film has been a box office success to a lesser or greater degree. They continue to earn substantial profits after their theatrical run via videotape, DVD, and television broadcasts. In the UK, Bond holds three of the top five top spots of the most-watched television movies.

By the 1980s, many critics had grown tired of the films, commenting that the perennial sexism and glamorous locales had become outdated, and that Bond’s smooth, unruffled exterior didn't mesh with competing movies like Die Hard. The hard-edge of Timothy Dalton in the Bond movies of the late 80s met a mixed response from moviegoers; some welcomed the earthier style reminiscent of Fleming's character, while others missed the light-hearted approach which characterised the Roger Moore era. While 1989's Licence to Kill was financially successful, it did not prove as popular as previous Bond films, due in part to a low-key promotional campaign in the United States. A new Bond film was announced for release in 1991, however legal wrangling over ownership of the character led to a protracted delay that would keep Bond off movie screens for the next six years.

The 1990s saw a revival and renewal of the series beginning with GoldenEye in 1995. Pierce Brosnan filled Bond’s shoes with an elegant mix of Sean Connery cool and Roger Moore wit.

James Bond has long been a household name and remains a huge influence within the cinematic spy film genre. The Austin Powers series and other parodies such as Johnny English (2003), and Casino Royale (1967) are testaments to Bond's prominence in popular culture (see: James Bond parodies). 1960s TV imitations of James Bond such as I Spy, Get Smart, The Wild Wild West, and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. went on to became popular successes in their own right. (Fleming contributed to the creation of U.N.C.L.E.; the show's lead character, "Napoleon Solo", was named after a character in Fleming's novel Goldfinger and Fleming also suggested the character name April Dancer which was later used in the spin-off series The Girl from U.N.C.L.E..)

Character's biography

Template:Spoiler James Bond is the son of a Scottish father, Andrew Bond, and a Swiss mother, Monique Delacroix, both of whom died in a mountain climbing accident in the Aiguilles Rouges, when Bond was 11 years old. James went to live with his Aunt, Miss Charmian Bond, in Kent. Bond's family motto, which was later adopted by James Bond during "Operation Corona" in the novel On Her Majesty's Secret Service is Orbis non sufficit (Latin for "The world is not enough").

With the exception of the Young Bond series of novels by Charlie Higson launched in 2005, Bond for the most part is an ageless character in both films and literature. He is roughly in his late thirties (the age of 37 can be deduced from Moonraker). According to John Pearson's James Bond: The Authorized Biography of 007, Bond was born on November 11, 1920; no Fleming novel supports this date. According to an obituary of James Bond in the novel You Only Live Twice, Bond left school when he was 17 years old and joined the Ministry of Defence in 1941. If Bond was 17 in 1941, then he was born in 1924. Fleming also establishes that Bond bought his first car, a Bentley (driven in several early novels and the second Bond film, From Russia With Love), in 1933, contradicting both birthdates—he would have been too young to buy a car had he been born in either 1920 or 1924, though he might have purchased the vehicle at a later date. Many Fleming biographers agree that Fleming never really intended to write as many James Bond adventures as he did and to keep writing the novels he had to "tinker with Bond's early life" and change dates to ensure Bond was the appropriate age for the service, particularly due to a statement in Moonraker that 007 faced mandatory retirement from the 00 Section at age 45. The issue of the car is one such example. Ian Fleming Publications recognised this issue for their new series of novels featuring Bond as a teenager in the 1930s and along with its author, Charlie Higson, defined Bond being born in the year 1920 (no specific date has thus far been declared).

The continuation Bond novels by John Gardner and Raymond Benson published between 1981 and 2002 depict Bond as being active in the present day (with Gardner in particular tying Bond to then-current events such as the 1991 Gulf War). Gardner depicts Bond as being in early middle age at the time of License Renewed, making it likely that his version of the character must have been born sometime after that of Fleming's Bond. Benson's Bond appears to be patterned after Pierce Brosnan's film portrayal, suggesting a birth year in the early 1950s.

It is also debated where James Bond was born. According to Pearson, Bond was born near Essen, Germany; however, Charlie Higson, in his novel SilverFin claims Bond was born in Switzerland.

Bond briefly attended Eton College starting at the age of 12, but was expelled after two halves when some "alleged" troubles with one of his maids came to light. In Fleming's short story "From a View to a Kill," Bond admits to losing his virginity on his first visit to Paris at the age of 16. John Gardner's novel Brokenclaw also references this moment in Bond's life. After Eton, Bond attended and continued his education in the prestigious Fettes College in Edinburgh, Scotland. In "Octopussy", Fleming writes that Bond briefly attended the University of Geneva. With the exception of Fettes, Bond's attendance at these schools parallels Fleming's own life, as he attended these same schools.

In 1941, Bond lied about his age in order to enter the Royal Navy's Volunteer Reserve during World War II, from which he emerged with the rank of Commander before joining MI6. During his tenure writing James Bond novels in the 1980s and 1990s, Gardner promoted Bond to Captain, but he was subsequently demoted back to Commander in Benson's novels without explanation.

In both the literary and cinematic versions of On Her Majesty's Secret Service, James Bond marries, but his bride, Teresa di Vicenzo (Tracy), is killed on their wedding day by his archenemy, Ernst Stavro Blofeld; the event resonates in both versions of the character for many years thereafter. In the novels, Bond gets revenge in the following novel, You Only Live Twice, when he by chance comes across Blofeld in Japan, whilst the cinematic Bond takes on Blofeld in Diamonds Are Forever with mixed results.

Bond had one child, by Kissy Suzuki in You Only Live Twice, although he did not know of the boy's existence until sometime later. Exactly when he learned this is not known, however he is aware of his son, James Suzuki, by the time of Raymond Benson's short story "Blast From the Past."

In the novels (notably From Russia, With Love), Bond's physical description has generally been consistent: a three-inch, vertical scar on his left cheek (absent from the cinematic version); blue-grey eyes;a "cruel" mouth; short-cut, dark hair, a comma of which falls on his forehead (greying at the temples in John Gardner's novels), and (after Casino Royale) the faint scar of the Russian cyrillic letter "Ш" (SH) on the back of one of his hands (carved by a SMERSH agent).

The literary and cinematic secret agent's attitude towards his job is similar. Although licensed to kill, Bond dislikes killing—resorting to flippant jokes and off-hand remarks as after-the-fact relief, often misinterpreted as cold-bloodedness. Pearson's biography (disputed canonically) suggests Bond first killed as a teenager. The novel Goldfinger begins with Bond's memory haunted by the small-time, Mexican gunman he had killed with his bare hands days earlier. In the films, there is a subtle hint in GoldenEye that he might be haunted so, and, in The World Is Not Enough, he admits that cold-blooded killing is a filthy business. Nonetheless, James Bond kills when needed, and on film commits acts that might be considered murder in other circumstances (in Dr. No, shooting Professor Dent in the back; killing the unarmed Elektra King in The World Is Not Enough). The literary James Bond was reserved in his licensed killing; there are Fleming works in which Bond does not kill anyone.

The cinematic Bond is famous for ordering his vodka martinis "shaken, not stirred." The literary Bond prefers vodka, but also drinks gin martinis, and in Casino Royale orders a martini that includes both types of liquor. Bond initially calls it "The Vesper" martini, after his lover in that book, Vesper Lynd. Throughout the novels, 007 orders his martinis with a slice of lemon peel (Fleming felt that olives were added by bartenders to decrease the amount of liquor in the drink), though this only occurs on film in Dr. No. In real life, martini bars often dub a martini made "shaken, not stirred" as a "Martini James Bond." (See martini cocktail for a detailed description of how a shaken martini differs from a stirred one). In the novels, most of the drinks that Bond has—beyond Casino Royale—aren't martinis at all.

Age is the notable difference between the literary and the cinematic versions of James Bond. As noted above, per Fleming's novel Moonraker, agent 007 faced mandatory retirement from active duty at age 45, while many of the films feature a considerably older hero. Assuming the correctness of either the 1920 or 1924 birthdates, Fleming's Bond would have retired between 1964 (coincidentally the year Fleming died) and 1969 (after Colonel Sun's 1968 publication). Pearson's biography suggests Bond continued working for MI6 as a special agent, beyond retirement age, and continued serving as agent 007 into the 1970s. John Gardner's version of James Bond is a man born after Fleming's version, since he remains an active agent in the 1980s and the 1990s, while Benson's hero serves as 007 in the 1990s and 2000s, suggesting a later birthdate than Gardner's version.

The cinematic James Bond (introduced in 1962) already had a history with MI6. In Dr. No, when reluctantly re-equipped with a 7.65 mm Walther PPK pistol replacing his under-powered .25 calibre Beretta automatic pistol, agent 007 protests, telling M that he has used the weapon for ten years, suggesting he has been a secret agent for at least that long.

Bond in the films is a graduate with a degree in Oriental languages from Cambridge University, as stated in You Only Live Twice—contradicting the novels, and Tomorrow Never Dies, wherein he cannot use a Chinese computer keyboard. Raymond Benson's Tomorrow Never Dies novelisation suggests Bond lied to Miss Moneypenny about his language degree in the earlier film. In The World Is Not Enough, he speaks Russian fluently, claiming he studied at Oxford (while he was impersonating a Russian scientist). Bond can also be seen in other films speaking a variety of different languages.

Although never stated outright, in his books, Fleming drops hints that Bond was smuggled into Hungary during its anti-Soviet uprising in 1956. A popular legend holds that a British secret agent was sent to Hungary to attempt to train the rebels, although they eventually lost. Using his literary licence, Fleming implies that Bond was this agent.

Books

By Ian Fleming

In January 1952, Ian Fleming began work on his first James Bond novel. At the time, Fleming was the Foreign Manager for Kemsley Newspapers, an organisation owned by the London Sunday Times. Upon accepting the job, Fleming asked that he be allowed two months vacation per year. Every year thereafter until his death in 1964, Fleming would retreat for the first two months of the year to his Jamaican house, "Goldeneye" to write a James Bond novel.

Between 1953 and 1966, twelve James Bond novels and two short story collections by Fleming were published, with one novel and one short story collection issued posthumously. To this day, it is still debated whether Fleming himself actually finished 1965's The Man with the Golden Gun, as he died very soon after completing the book. His first anthology of short stories, For Your Eyes Only mostly consisted of converted screenplays for a CBS television series based on the character. When the project fell through, Fleming turned them into short stories: (i) "From a View to a Kill", (ii) "For Your Eyes Only", (iii) "Risico", plus two additional stories, "The Hildebrand Rarity" and "Quantum of Solace", which were previously published. The second anthology, Octopussy and The Living Daylights (in many editions titled only Octopussy), originally only contained two short stories, "Octopussy" and "The Living Daylights"; a third story, "The Property of a Lady" was added in the 1967 paperback edition, and a fourth, "007 in New York", was added in 2002.

Post-Fleming James Bond novels

Following Ian Fleming's death in 1964, Glidrose Productions, publishers of the James Bond novels, planned a new book series, credited to the pseudonym "Robert Markham" and written by a rotating series of authors. Ultimately, only one Markham novel saw print, 1968's Colonel Sun by Kingsley Amis. Amis had previously written two books on the world of James Bond, the 1964 essay The James Bond Dossier and the tongue-in-cheek 1965 release The Book of Bond, or Every Man His Own 007 (written under the pseudonym "Lt.-Col. William ("Bill") Tanner", a recurring character in the Bond novels. Amis had also been claimed for many years as the ghost writer of The Man with the Golden Gun, although this has been debunked by numerous sources. (See The controversy over The Man with the Golden Gun.)

In 1973, Ian Fleming biographer John Pearson was commissioned by Glidrose to biograph the fictional character James Bond. Pearson wrote James Bond: The Authorized Biography of 007 in the first person as if meeting the secret agent himself. The book was well-received by aficionados—readers and viewers, alike. Since the book has many discrepancies with Fleming's Bond (for example his birth year), the canonical status of James Bond: The Authorized Biography of 007 is debated among fans—some consider it apocryphal, though at least one publisher issued it as an official novel along with the rest of Fleming's series. Glidrose reportedly considered a new series of novels written by Pearson, but this did not come to pass. Prior to writing this, Pearson had written an early biography of Ian Fleming, The Life of Ian Fleming.

In 1977, the film The Spy Who Loved Me was released and was subsequently novelised and published by Glidrose due to the radical difference between the script and Fleming's novel of the same name. This would happen again with 1979's Moonraker. Both novelisations were written by screenwriter Christopher Wood and were the first official novelisations, although technically, Fleming's Thunderball was a novelisation having been based on scripts by himself, Kevin McClory, and Jack Whittingham (although it predated the movie), and the For Your Eyes Only collection was also, for the most part, based upon unproduced scripts.

In the 1980s, the series was finally revived with new novels by John Gardner; between 1981 and 1996, he wrote fourteen James Bond novels and two screenplay novelisations, surpassing Fleming's original output. The biggest change in Gardner's series was updating 007's world to the 1980s; however, it would keep the characters the same age as they were in Fleming's novels. Generally Gardner's series is considered a success although their canonical status is disputed.

|

|

In 1996, John Gardner retired from writing James Bond books due to ill health, and American Raymond Benson quickly replaced him. As a James Bond novelist, Raymond Benson was initially controversial for being American, and for ignoring much of the continuity established by Gardner. Benson had previously written The James Bond Bedside Companion, a book dedicated to Ian Fleming, the official novels, and the films. The book was initially released in 1984 and later updated in 1988. Benson also contributed to the creation of several modules in the popular James Bond 007 role-playing game in the 1980s. Benson wrote six James Bond novels, three novelisations, and three short stories.

|

|

Benson abruptly resigned as Bond novelist at the end of 2002, despite having previously announced plans to write a short story collection. Low sales figures for the books, and plans by Ian Fleming Publications to focus on reissuing Fleming's original novels for the 50th anniversary of the character, were among reasons speculated by fans as to why Benson departed. The year 2003 marked the first year since 1980 that a new James Bond novel had not been published.

On August 28, 2005, Ian Fleming Publications confirmed it is planning to publish a one-off adult Bond novel in 2008 to mark what would have been Ian Fleming's 100th birthday. This would feature the adult version of the character as opposed to the "Young Bond" character of the recent Charlie Higson books (see below). Although it has been suggested a "big name" author might take on the task, the publishers have yet to approach anyone about this project [2].

Young Bond

In April 2004, Ian Fleming Publications (Glidrose) announced a new series of James Bond books. Instead of continuing from where Raymond Benson ended in 2002, the new series would feature James Bond as a thirteen-year-old boy attending Eton College. Written by Charlie Higson (The Fast Show) the series is expected to align with the adult Bond's back-story established by Fleming and Fleming only. Since the concept was announced the series has taken heavy criticism for being aimed at the "Harry Potter audience" and has been seen by some as a desperate attempt to find a new audience for Bond. Regardless, the first novel became a bestseller in the United Kingdom and was released to good reviews. A second novel is due for release in January 2006. The series is currently planned out for five novels according to Charlie Higson.

|

The Young Bond series is expected to be expanded to include graphic novels in 2006. It is currently unknown whether these will be adaptations of Higson's books or original adventures.

The Moneypenny Diaries

In May 2005 it was revealed that a new trilogy of novels edited by Kate Westbrook called The Moneypenny Diaries will be released by John Murray publishers that will centre on the character of Miss Moneypenny. While not initally authorised by Ian Fleming Publications, it was sanctioned after detailed negotiations [3]. The first installment of the trilogy is scheduled for release on October 10, 2005.

The novels had originally been touted as the secret journal of a colleague of the "real" James Bond, but the publishers admitted on 28 August 2005 that they were a spoof after an investigation by The Sunday Times of London.

Roland Philipps, managing director of John Murray, originally said: “From the moment I heard about this remarkable discovery I knew it would be a crucial piece of historical record from a previously unpublished source.”

Westbrook is said to be niece of the "real" Jane Moneypenny and the diaries were "discovered" after her death in 1990. It was also claimed that Westbrook was a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. But the college — where the Soviet spies Kim Philby, Donald Maclean and Anthony Blunt studied in the 1930s — denied knowledge of her.

Other Bond-related fiction

In 1967, Glidrose authorised publication of 003½: The Adventures of James Bond Junior written by Arthur Calder-Marshall under the pseudonym R D Mascott. This book is for young-adult readers, and chronicles the adventures of 007's nephew (despite the inaccurate title).

An early 1990s animated television series, James Bond Jr, ran for 65 episodes and spawned a six-episode novelisation series written by John Peel under the pseudonym John Vincent. (There appears to be no connection between this series and the 1967 book by Marshall).

Russians were often the villains in Fleming's Cold War-era novels in at least some form. In 1968, they hit back with a spy novel of their own called The Zakhov Mission by Andrei Guliashki, in which a communist hero finally and forcefully defeats 007.

In addition to numerous fan fiction pieces written since the character was created, there have been two stories written by well-known authors claiming to have been contracted by Glidrose. The first in 1966, was Per Fine Ounce by Geoffrey Jenkins, a friend of Ian Fleming who claimed to have developed with Fleming a diamond-smuggling storyline similar to Diamonds Are Forever as early as the 1950s. According to the book The Bond Files by Andy Lane and Paul Simpson, soon after Ian Fleming died, Glidrose Productions commissioned Jenkins to write a James Bond novel. The novel was never published. Some sources have suggested that Jenkins novel was to be published under the Markham pseudonym. The second story, 1985's The Killing Zone by Jim Hatfield goes so far as to have been privately published as well as claim on the cover that it was published by Glidrose; however it is highly unlikely that Glidrose contacted Hatfield to write a novel since at the time John Gardner was the official author. The text of The Killing Zone is available on the Internet and can be found here.

In 1997, the British publisher B.T. Batsford produced Your Deal, Mr. Bond, a collection of bridge-related short stories by Phillip King and Robert King. The title story features James Bond, M, and other characters and features an epic bridge game between Bond and the villain, Saladin. No credit is given to Ian Fleming Publications, suggesting this rare story may have been unauthorized; a photo of Sean Connery as Bond is featured on the cover of the book.

Official films

The James Bond film series has its own traditions, many of which date back to the very first movie in 1962.

Since Dr. No, every official James Bond film begins with what is known as the "gun barrel shooting scene", which introduces agent 007. The gun barrel is seen from the assassin's perspective—looking down at a walking James Bond, who quickly turns and shoots; the scene reddens (signifying the spilling of the gunman's blood), the gun barrel dissolves to a white circle, and the film begins.

In the first three films, stuntman Bob Simmons played the role of James Bond in the gun barrel sequence (making Simmons, technically, the first actor shown playing James Bond in a movie). Starting with Thunderball in 1965, every actor to portray Bond would be filmed in the scene. For the first film, Dr. No, opening credits designer Maurice Binder achieved the look with a pin hole camera shooting through a real gun barrel. In addition to Simmons, Sean Connery and George Lazenby were the only actors who would film the sequence while wearing a hat, while Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton, and Pierce Brosnan would wear tuxedos for their renditions. Beginning with 1995's GoldenEye, the gun barrel was computer-generated and later Die Another Day, being the twentieth Bond film, introduced an actual CG bullet being shot from Bond's gun and zooming towards the viewer.

After the gun barrel scene, every film starting with From Russia with Love (1963), would start with a pre-credits teaser, also popularly known as the "opening gambit." Usually the scene features 007 finishing up a previous case before taking on the case from the film, and does not always relate to his main mission. Some of the teasers tie in with the plot of the film (as in The Spy who Loved Me). Many teasers include a huge action sequence, which from film to film would get larger, crazier, and add more special effects than each previous film. The 1999 film The World Is Not Enough currently holds the record as the longest Bond teaser ever, running more than 15 minutes; most teasers run for less than five minutes.

When the teaser sequence is finished, the opening credits begin during which an arty display of scantily clad and even (discreetly) naked females can be seen doing a variety of activities from dancing, jumping on a trampoline, to shooting weapons. This sequence, initially designed by Maurice Binder for fourteen 007 films, is a trademark and a staple of the James Bond films. Since Binder's death in 1991, Daniel Kleinman has designed the credits and has introduced CG elements not present during Binder's era. While the credits run, the main theme of the film is usually sung by a popular artist of the time. For the most part, the credits are unrelated to the plot of the film, although the design may reflect an overall theme (for example, You Only Live Twice uses a Japanese motif as well as images of a volcano, both of which are elements of the movie itself). For Your Eyes Only begins with Sheena Easton singing the title song on-screen. Die Another Day was unusual in that the images shown in that film's opening credits advance the storyline. Beginning in the mid-1990s, it has become common for most films to be released without opening credits sequences; the Bond films are among the few exceptions.

Agent 007's famous introduction, "Bond. James Bond" became a catch phrase after it was first muttered (with a cigarette in the corner of his mouth) by Sean Connery in Dr. No. Since then, the phrase has entered the lexicon of Western popular culture as the epitome of polished, understated machismo. On June 21, 2005 the catch phrase was honoured as the 22nd greatest quote in cinema history by the American Film Institute as part of their 100 Years Series [4].

Every aficionado has a favourite James Bond: Sean Connery—the tough, his machismo ready beneath the polished persona, George Lazenby—the controversial ultra-macho man, equally loved and despised, Roger Moore—the sophisticate, rarely mussing his hair whilst saving the world, Timothy Dalton—the hard-edged literary character, and Pierce Brosnan—the polished, hard-edged man. In 2005, EON Productions is expected to announce the sixth official actor to play the role of secret agent 007.

Films

| No. | Title | Year | James Bond | Worldwide Box Office Gross |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dr. No | 1962 | Sean Connery | $59,600,000 |

| 2 | From Russia With Love | 1963 | Sean Connery | $78,900,000 |

| 3 | Goldfinger | 1964 | Sean Connery | $124,900,000 |

| 4 | Thunderball | 1965 | Sean Connery | $141,200,000 |

| 5 | You Only Live Twice | 1967 | Sean Connery | $111,600,000 |

| 6 | On Her Majesty's Secret Service | 1969 | George Lazenby | $87,400,000 |

| 7 | Diamonds Are Forever | 1971 | Sean Connery | $116,000,000 |

| 8 | Live and Let Die | 1973 | Roger Moore | $161,800,000 |

| 9 | The Man with the Golden Gun | 1974 | Roger Moore | $97,600,000 |

| 10 | The Spy Who Loved Me | 1977 | Roger Moore | $185,400,000 |

| 11 | Moonraker | 1979 | Roger Moore | $210,300,000 |

| 12 | For Your Eyes Only | 1981 | Roger Moore | $195,300,000 |

| 13 | Octopussy | 1983 | Roger Moore | $187,500,000 |

| 14 | A View to a Kill | 1985 | Roger Moore | $152,400,000 |

| 15 | The Living Daylights | 1987 | Timothy Dalton | $191,200,000 |

| 16 | Licence to Kill | 1989 | Timothy Dalton | $156,200,000 |

| 17 | GoldenEye | 1995 | Pierce Brosnan | $353,400,000 |

| 18 | Tomorrow Never Dies | 1997 | Pierce Brosnan | $346,600,000 |

| 19 | The World Is Not Enough | 1999 | Pierce Brosnan | $390,000,000 |

| 20 | Die Another Day | 2002 | Pierce Brosnan | $456,000,000 |

| 21 | Casino Royale | 2006 | To be announced |

Every film, except Dr. No (1962), has the line: "James Bond will return. . ." or "James Bond will be back" during or after the final credits. Up until Octopussy (1983) the end-credit line would also name the next title in the film series ("James Bond will return in..."). Over the years the films have incorrectly named the sequel three times. The first, 1964's Goldfinger, in early prints announced Bond to return in On Her Majesty's Secret Service, however, the producers changed their mind shortly after release and subsequently made the correction in future prints of the film. In 1977, The Spy Who Loved Me stated Bond would return in For Your Eyes Only, however, EON Productions had decided to instead take advantage of the Star Wars space craze and release a film adaptation of Fleming's Moonraker, which was changed to a plot involving outer space. Thirdly, Octopussy (1983) incorrectly states the title of the next film as From A View To A Kill, the original literary title of A View to a Kill.

Music

"The James Bond Theme" was written by Monty Norman and was first orchestrated by the John Barry Orchestra for 1962's Dr. No, although the actual authorship of the music has been a matter of controversy for many years. Barry went on to compose the soundtracks for eleven Bond films in addition to his uncredited contribution to Dr. No, and is credited with the creation of "007", which was used as an alternate Bond theme in several films, and the popular orchestrated theme "On Her Majesty's Secret Service". Both "The James Bond Theme" and "On Her Majesty's Secret Service" have been remixed a number of times by popular artists, including Art of Noise, Moby, Paul Oakenfold, and the Propellerheads.

Barry's legacy was followed by David Arnold, in addition to other well-known composers and record producers such as George Martin, Bill Conti, Michael Kamen, Marvin Hamlisch, and Eric Serra. Arnold is the series' current composer of choice, and was recently signed to compose the score for the his fourth consecutive Bond film, Casino Royale.

On Her Majesty's Secret Service is the only Bond film with a solely instrumental theme. The main theme for Dr. No is the "James Bond Theme", although the opening credits also include an untitled bongo interlude, and concludes with a vocal Calypso-flavoured rendition of "Three Blind Mice" entitled "Kingston Calypso" that sets the scene. From Russia With Love also opens with an instrumental version over the title credits (which then segues into the James Bond Theme), but Matt Monro's vocal version also appears twice in the film, including the closing credits; the Monro version is generally considered the film's main theme, even though it doesn't appear during the opening credits.

In addition to the nowadays typically truncated version of The James Bond Theme which is always heard at the beginning, the tune is also often used in an action scene somewhere in the film. In a somewhat surreal moment in Octopussy, an Indian snake charmer plays the tune for Bond on his flute, and Bond makes a remark about the tune, suggesting that the movie character would be aware of his own theme music.

During the title credits a popular artist usually sings the theme of the film. Shirley Bassey has performed the most with three theme songs. Some other performers include Tina Turner, Duran Duran, Tom Jones, Paul McCartney, Nancy Sinatra, Carly Simon, Gladys Knight, a-ha, Sheryl Crow, Sheena Easton, Garbage and Madonna.

Trivia

- Many people assume the Bond producers would never hire an American to portray the character in the official film series, but American actors have been hired on two occasions and asked on several others. Adam West was offered the chance to appear in On Her Majesty's Secret Service when Sean Connery chose not to return to the role, but turned down the offer. John Gavin was hired in 1970 to replace George Lazenby, but Connery was lured back at the eleventh hour and it was he who appeared in Diamonds Are Forever instead of Gavin. Burt Reynolds was also asked by Cubby Broccoli in the early 70s to replace Connery after Diamonds Are Forever, but turned it down. James Brolin was hired in 1983 to replace Roger Moore, and was preparing to shoot Octopussy when the producers convinced Moore to return. Several other American actors, including Patrick McGoohan and Robert Wagner, have been offered the role only to turn it down. To date the only American to play the role is Barry Nelson, although unofficially in the Americanised version of the character in the 1954 TV adaptation of Casino Royale.

- Roger Moore is the only English actor to have played Bond in the official film series. Sean Connery is Scottish, George Lazenby is Australian, Timothy Dalton is of mixed Italian and Welsh descent (and born in Wales), and Pierce Brosnan is Irish.

- While initially sceptical about Sean Connery being chosen to play Bond (at one point dismissing him as an "overgrown stuntman"), Ian Fleming liked his portrayal so much that he eventually changed the background of the character in the novels so that his father was Scottish. Roger Moore was reportedly Fleming's initial first choice for the Bond role.

Unofficial films

In 1954, CBS paid Ian Fleming $1,000 US for the rights to adapt Casino Royale into a one hour television adventure as part of their Climax! series. The episode featured American Barry Nelson in the role of "Jimmy Bond", an agent for the fictional "Combined Intelligence" agency. The rights to Casino Royale were subsequently sold to producer Charles K. Feldman who turned Fleming's first novel into a spoof featuring actor David Niven as one of six James Bonds. The instrumental theme music was a hit for Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass. For more information, see the history of Casino Royale.

When plans for a James Bond film were scrapped in the late 1950s, a story treatment entitled Thunderball, written by Ian Fleming, Kevin McClory and Jack Whittingham, was adapted as Fleming's ninth Bond novel. Initially the novel only credited Fleming. McClory filed a lawsuit that would eventually award him the film rights to the novel in 1963. Afterwards McClory made a deal with EON Productions to produce a film adaptation starring Sean Connery. The deal specifically stated that McClory couldn't reproduce another adaptation until a set period of time had elapsed. McClory did so in 1983 by producing the film Never Say Never Again, which featured Sean Connery for a seventh time as 007. Never Say Never Again was not made by Broccoli's production company, EON Productions, and is, therefore, not considered a part of the official film series. A third attempt by McClory to remake Thunderball in the 1990s with Sony Pictures was halted by legal action which resulted in Sony Pictures abandoning their aspirations for a rival James Bond series. McClory to this day still claims to own the film rights to Thunderball, though MGM and EON claim those rights have expired. For more in-depth information, see the controversy over Thunderball.

| Title | Year | James Bond | Worldwide Box Office Gross |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casino Royale — TV episode | 1954 | Barry Nelson | not applicable |

| Casino Royale — Film spoof | 1967 | David Niven | $44,000,000 |

| Never Say Never Again | 1983 | Sean Connery | $160,000,000 |

Bond characters

- Main articles: List of James Bond allies, List of James Bond villains, Bond Girls

The James Bond series of novels and films have a plethora of interesting allies and villains. Bond's superiors and other officers of MI6 are generally known by letters such as M and Q. In the novels (but not in the films), Bond has had two secretaries, Mary Goodnight and Loelia Ponsonby, who in the films typically have their roles and lines transferred to M's secretary Miss Moneypenny. Occasionally Bond is assigned to work a case with his good friend, Felix Leiter of the CIA. Indeed, during many of the novels and early films, Leiter was the most prominently featured recurring character other than Bond himself, appearing fairly regularly. However, he was almost always played by a different actor.

Bond's women, particularly in the films, often have double entendre names, leading to coy jokes, for example, "Pussy Galore" in Goldfinger (a name invented by Fleming), "Plenty O'Toole" in Diamonds Are Forever, and "Xenia Onatopp" (a villainess sexually excited by strangling men with her thighs) in GoldenEye. Despite Bond's male chauvinism towards women, most end up, if not in love with him, at least subdued by him.

Throughout both the novels and the films there have only been a handful of recurring characters. Some of the more memorable ones include Bill Tanner, Rene Mathis, and Jack Wade.

Vehicles & gadgets

Exotic espionage equipment and vehicles are very popular elements of James Bond's literary and cinematic missions; these items often prove critically important to Bond removing obstacles to the success of his missions.

Fleming's novels and early screen adaptations presented minimal equipment such as From Russia With Love's booby-trapped attaché case; in Dr. No, Bond's sole gadgets were a geiger counter and a wristwatch with a luminous (and radioactive!) face. The gadgets, however, assumed a higher, spectacular profile in the 1964 film Goldfinger; its success encouraged further espionage equipment from Q Branch to be supplied to 007. Some films, in the opinion of many critics and fans, have had excessive amounts of gadgets or extremely outlandish gadgets and vehicles, specifically 1979's science fiction-oriented Moonraker and 2002's Die Another Day in which Bond's Aston Martin could cloak itself. Since Moonraker subsequent productions struggled with balancing gadget content against the story's capacities, without implying a technology-dependent man, to mixed results.

Bond's most famous car is the silver grey Aston Martin DB5 seen in Goldfinger, Thunderball, GoldenEye, and Tomorrow Never Dies. In Fleming's books, Bond has a penchant for "battleship grey" Bentleys, while Gardner awarded the agent a modified Saab 900 Turbo nicknamed the Silver Beast.

Video games

In 1983, the first Bond video game, developed and published by Parker Brothers, was released for the Atari 2600, the Atari 5200, the Commodore 64, and the Colecovision. Since then, there have been numerous video games either based on the films or using original storylines.

Bond video games, however, didn't reach their popular stride until 1997's GoldenEye 007 by Rare for the Nintendo 64. Subsequently, virtually every Bond video game has attempted to copy GoldenEye 007's accomplishment and features to varying degrees of success. In 2004, Electronic Arts released a game entitled GoldenEye: Rogue Agent that had nothing to do with either the video game GoldenEye or the film of the same name, and Bond himself plays only a minor role in which he is killed in the beginning during a virtual mission similar to the opening scene in the film From Russia With Love.

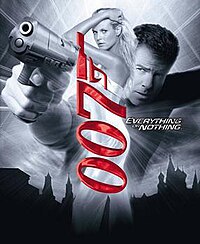

Electronic Arts has to date released seven games, including the popular Everything or Nothing, which broke away from the first-person shooter element found in GoldenEye and went to a third-person perspective. It was also the first game to feature well known actors including Willem Dafoe, Heidi Klum and Pierce Brosnan as James Bond, although several previous games have used Brosnan's likeness as Bond. In 2005, Electronic Arts will release a video game adaptation of From Russia With Love, which will allow the player to play as Bond with the likeness of Sean Connery. This will be only the second game based on a Connery Bond film (the first was a 1980s text adventure adaptation of Goldfinger) and the first to use the actor's likeness as agent 007. Connery himself will be recording new voiceovers for the game, the first time the actor has played Bond in 22 years.

Comic strips and comic books

In 1957 the Daily Express, a newspaper owned by Lord Beaverbrook, approached Ian Fleming to adapt his stories into comic strips. After initial reluctance by Fleming who felt the strips would lack the quality of his writing, agreed and the first strip Casino Royale was published in 1958. Since then many illustrated adventures of James Bond have been published, including every Ian Fleming novel as well as Kingsley Amis' Colonel Sun, and most of Fleming's short stories. Later, the comic strip produced original stories, continuing until 1983.

Several comic book adaptations of the James Bond films have been published through the years, as well.

Other films pertaining to James Bond

The James Bond films and novels have been repeatedly parodied and copied since the introduction of the onscreen character in 1962. Some of these parodies have been successful box office draws such as the Austin Powers series of films by writer and actor Mike Myers and the "Flint" series starring James Coburn as Derek Flint in films such as Our Man Flint (1966) and In Like Flint (1967).

There have also been various films that have attempted to copy Bond's successful features such as the most recent xXx.

A reunion television movie, The Return of the Man from U.N.C.L.E. (1983) featured a cameo by George Lazenby as James Bond from On Her Majesty's Secret Service; (for legal reasons, his character was credited as "JB"). Ian Fleming helped create the original The Man from U.N.C.L.E. TV series in the 1960s, so "JB's" appearance is a tribute.

See also

- 9007 James Bond (Asteroid named after the character)

References

- ^ "James Bond the second highest grossing film franchise of all time". Most Lucrative Movie Franchises. June 15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ ""Bond. James Bond" 22nd greatest line in cinema history". AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes. July 13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - . ISBN 1401102840.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 1860643876.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 0810932962.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 0719065410.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - "Charlie Higson interview with CommanderBond.net". The Charlie Higson CBn Interview. February 23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help)

- Bond franchise Box Office numbers [5], Casino Royale Box Office numbers (1967), Box Office numbers + Inflation

External links

Official sites

- James Bond Official Homepage

- Official Danjaq 007 website

- Ian Fleming Publications official website

- Miss Moneypenny's Rolodex

Fan sites

- MI6.co.uk - The home of James Bond

- The Albert R. "Cubby" Broccoli Tribute Site

- Absolutely James Bond

- Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang!

- CommanderBond.net

- James Bond, Agent 007 OHMSS

- Art of James Bond

- James Bond International Fan Club

- The James Bond Dossier

- Bondian.com: extensive Bond literature site

- James Bond first edition bibliographies

- "Make Mine a 007..."

- James Bond Multimedia

- Cubby's Place: The Man Behind Bond

- Universal Exports

- Classic Movies (1939 - 1969): James Bond

- Q-Branch