History of the Han dynasty

The Han Dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), founded by the rebel peasant leader Liu Bang (reigned as Emperor Gaozu, 202–195 BCE), was the second imperial dynasty of China following the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE), which had unified the Warring States of China by conquest. Interrupted briefly by the Xin Dynasty (9–23 CE) of Wang Mang, the Han Dynasty is divided into two periods: the Western Han (202 BCE – 9 CE) and Eastern Han (25–220 CE), these appellations derived from the locations of the capital cities Chang'an and Luoyang, respectively. The third and final capital of the dynasty was Xuchang, where the court moved in 196 during a period of political turmoil and civil war.

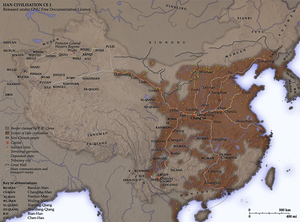

The Han Dynasty ruled in an era of Chinese cultural consolidation, political experimentation, relative economic prosperity and maturity, and unprecedented territorial expansion and exploration initiated by struggles with non-Chinese peoples, especially the nomadic Xiongnu of the Eurasian Steppe. The Han emperors were initially forced to acknowledge the rival Xiongnu shanyus as their equals, yet in reality were inferior partners in a tributary and royal marriage alliance known as heqin. This agreement was broken when Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BCE) launched a series of military campaigns which eventually caused the fissure of the Xiongnu Federation and redefined the borders of China. The Han realm was expanded into the Hexi Corridor of modern Gansu province, the Tarim Basin of modern Xinjiang, modern Yunnan and Hainan, modern northern Vietnam, modern North Korea, and southern Outer Mongolia. For the first time in Chinese history, the Han court established trade and tributary relations with a ruler in Japan and states as far west as Parthia of Persia. They also made a diplomatic effort to reach the Roman Empire, while Romans allegedly paid tribute to the Han court. Buddhism first entered China during the Han, spread by missionaries from Parthia and the Kushan Empire of northern India and Central Asia.

From its beginning, the Han imperial court was dogged by plots of treason and revolt from its subordinate kingdoms, eventually ruled only by royal Liu family members. Initially, the eastern half of the empire was administered by large semi-autonomous kingdoms who paid loyalty and a portion of their tax revenues to the Han emperors, who ruled directly over the western half of the empire from Chang'an. Gradual measures were introduced by the imperial court to reduce the size and power of these kingdoms, until a reform of the middle 2nd century BCE abolished their semi-autonomous rule and staffed the kings' courts with central government officials. Yet much more volatile and consequential for the dynasty was the growing power of both consort clans (of the empress) and the eunuchs of the palace. In 92 CE, the eunuchs entrenched themselves for the first time in the issue of the emperors' succession, causing a series of political crises which culminated in 189 with their downfall and slaughter in the palaces of Luoyang. This event triggered an age of civil war as the country became divided by regional warlords vying for power. Finally, in 220 CE, the son of an imperial chancellor and king accepted the abdication of the last Han emperor, who was deemed to have lost the Mandate of Heaven according to Dong Zhongshu's (179–104 BCE) cosmological system that involved the earthly imperial government. Following the Han, China was split into Three Kingdoms: Cao Wei, Shu Han, and Eastern Wu, kingdoms which were reconsolidated into one empire by the Jin Dynasty (265-420).

Fall of Qin and Chu-Han conflict

Collapse of Qin

The early Zhou Dynasty (c. 1050–256 BCE) established the frontier State of Qin in Western China as an outpost to breed horses and act as a defensive buffer against northern nomadic armies of the Rong, Qiang, and Di peoples.[1] After a long period of building strength, from 230 to 221 BCE the armies of Qin marched on and conquered six different Warring States: Han, Zhao, Wei, Chu, Yan, and Qi.[1] After consolidating control over much of China proper, the King of Qin, Ying Zheng 嬴政 formally acknowledged his enhanced prestige by creating the regnal title huangdi 皇帝, or 'emperor'.[2] He was the first to unify the Warring States, dissolving them into thirty-six centrally-controlled commanderies under one empire.[2]

Despite three assination attempts, the first emperor of Qin, Shihuangdi, died naturally in 210 BCE.[3] Within a year, malcontents opposed to the rule of Qin revolted against the regime. In 209 BCE the conscription officers Chen Sheng and Wu Guang, leading nine hundred conscripts through the rain, failed to meet an arrival deadline; the Standard Histories claim that the prescribed Qin punishment would have been execution.[4] In an effort to avoid punishment, Chen and Wu fled from office and started the first popular rebellion against Qin, but were crushed by the Qin general Zhang Han in the fourth month of 208 BCE.[4] Before they were suppressed, however, other subjects had turned to rebellion, such as Xiang Yu (d. 202 BCE) and his uncle Xiang Liang 项梁, men from a leading family in Chu.[5] After killing a governor in what is now Jiangsu province and gaining the support of several thousand, Xiang Yu and Xiang Liang were joined by Liu Bang 劉邦, a supervisor of convicts in Pei County who had overthrown the Qin magistrate there.[5] Mi Xin 羋心, a grandson of a Warring States ruler of Chu, was crowned King of Chu at his powerbase of Pengcheng (modern Xuzhou) with the support of the Xiangs, while other kingdoms soon formed in opposition to Qin.[6] When the Qin officer Zhang Han besieged the rebel city of Julu in the new Kingdom of Zhao, the new kingdoms of Chu, Yan, and Qi came to its relief.[6] Despite this, Xiang Liang was killed and Xiang Yu took his place as de facto leader of the rebels; in 207 he forced the surrender of Zhang Han.[6]

While Xiang Yu was occupied at Julu, the King of Chu had sent Liu Bang to capture Guanzhong with an agreement that the first officer to take this heartland of Qin would be made King of Guanzhong.[7][8] In late 207 BCE, the Qin ruler Zi Ying, whose status was reduced from an emperor to a King of Qin 秦王, had his chief eunuch Zhao Gao killed after the latter orchestrated the deaths of both the Chancellor Li Si in 208 and the second ruler Qin Er Shi in 207.[9] Liu Bang gained the submission of Zi Ying and secured the Qin stronghold at Xianyang;[9] he was persuaded by Zhang Liang and Fan Kuai not to let his soldiers loot the city and instead sealed up its treasury.[10]

Chu versus Han

It is alleged in the Standard Histories that when Xiang Yu arrived at Xianyang two months later in early 206, he looted it, burned it to the ground, and executed Zi Ying and his royal family.[9][11] In that year, Xiang Yu granted the King of Chu the nominal title Emperor Yi of Chu, but then had him sent to the remote frontier where he was assassinated; Xiang Yu then assumed the title King Protector of Chu, and led a confederacy of eighteen kingdoms.[12] At the Feast at Hong Gate, Xiang Yu plotted to have Liu Bang assassinated, but the attempt failed.[10][13] In a slight towards Liu Bang, Xiang Yu carved Guanzhong into three kingdoms led by former Qin generals including Zhang Han; Liu Bang was granted the frontier Kingdom of Han in Hanzhong, where he would pose less of a political challenge to Xiang Yu.[11][12]

In the summer of 206 BCE, Liu Bang heard of Emperor Yi's fate and decided to rally some of the new kingdoms to oppose the new Chu ruler Xiang Yu.[14] Liu Bang's initial siege against Pengcheng was a failure which he barely escaped; he was saved by a storm which delayed the arrival of Chu's troops.[14] Liu Bang barely escaped another defeat at Xingyang, yet Xiang Yu was unable to pursue him due to Han Xin's (d. 196 BCE) simultaneous assault to the east.[15] After Liu Bang occupied Chenggao, Xiang Yu met him at Guangwu and, with both armies facing each other from opposite banks of the Yellow River, threatened to kill Liu's hostage father if he did not surrender.[15] After being wounded by an arrow, Liu Bang withdrew into Chenggao, Xiang Yu besieged him there, but was forced to leave with some of his forces to meet attacks elsewhere.[15] Liu took the opportunity to open the city gates and attack the besiegers outside; when Xiang Yu hastily returned, Liu Bang had already fled.[15]

After years of fighting, in 203 BCE Xiang Yu offered a truce in which he would release Liu Bang's family members from captivity and split China into political halves: the west would go to Han and the east would belong to Chu.[15] Although Liu accepted the truce, it was short-lived, and in 202, at Gaixia in modern Anhui, the Han forces forced Xiang Yu to flee from his fortified camp with only 800 cavalry in the early morning, pursued by 5,000 Han cavalry sent by Liu Bang once he was awoken at camp.[16] After several bouts of fighting, Xiang Yu became surrounded at the banks of the Yangzi River, where he committed suicide.[17] At the urging of his followers, Liu Bang accepted the title of emperor, and is known to posterity as Emperor Gaozu of Han (r. 202–195 BCE).[17]

Reign of Gaozu

Consolidation, precedents, and kingly rivals

Moving from Luoyang, which he designated as his capital in early 202, Emperor Gaozu occupied Chang'an (near modern Xi'an, Shaanxi) as the new imperial capital. The move was dictated by concerns about natural defences and better access to supply routes.[18] From the Qin precedent, Emperor Gaozu adopted the earlier administrative model of a tripartite cabinet (formed by the Three Excellencies) along with nine subordinate ministries (headed by the Nine Ministers).[19] Despite Han statesmen's general condemnation of Qin's harsh methods and Legalist philosophy, the Han law code first compiled by Chancellor Xiao He in 200 BCE seems to have borrowed much from the structure and statutes of the previous Qin law code (excavated texts from Shuihudi and Zhangjiashan in modern times have reinforced this notion).[20][21][22]

From his base in Chang'an, Emperor Gaozu ruled directly over thirteen commanderies (increased to sixteen by his death) in the western portion of the empire.[25][26] In the eastern portion of the empire, to placate prominent loyal followers, ten semi-autonomous kingdoms were established (e.g. Yan, Dai, Zhao, Qi, Liang, Chu, Huai, Wu, Nan, and Changsha).[25][26] Initially established to restore law and order, the issue of the kings' loyalty to the Han court repeatedly came into question with acts of rebellion and even treasonous alliances made with the Xiongnu, a northern nomadic people.[25][26] To ensure loyalty, by 196 Emperor Gaozu had replaced nine of the ten kings with royal family members.[25][26] Only Wu Rui 吳芮, King of Changsha, remained as the only king not of the Liu clan, yet when he died without an heir in 157 BCE a Liu family member was made King of Changsha.[25] South of Changsha, Emperor Gaozu sent Lu Jia 陸賈 as ambassador to the court of Zhao Tuo to acknowledge the latter's sovereignty over Nanyue (in modern Southwest China and northern Vietnam; it is also known as the Triệu Dynasty in Vietnamese).[27]

According to Michael Loewe, the administration of each kingdom was "a small-scale replica of the central government, with its chancellor, royal counsellor, and other functionaries."[28] The kingdoms were to periodically conduct a population census, collect taxes, and transmit both census information and a portion of the taxes to the central government.[28] Although they were responsible for maintaining an armed force, kings were not authorized to mobilize any troops without explicit permission from the capital.[28]

Xiongnu and Heqin

When the Qin general Meng Tian (d. 210 BCE) forced Toumen, the shanyu 單于 of the nomadic Xiongnu, out of the Ordos Desert in 215 BCE, the Xiongnu were a much smaller power compared to the steppe empire built during the reign of Modu Shanyu (d. 174 BCE).[29][30] Initially subjugating the Donghu people in the east, by the time of Modu's death his conquered domains stretched from what is now Manchuria, Mongolia, and the Altai Mountains and Tian Shan mountain ranges of Central Asia.[31] The Chinese were fearful of incursions by the Xiongnu under the guise of trade and of Han-manufactured iron weapons falling into Xiongnu hands.[32] Thus, Gaozu made the Chinese border merchants of the northern kingdoms of Dai and Yan government officials with handsome salaries to compensate for lost trade, since he enacted a trade embargo against the Xiongnu; outraged by this, Modu Shanyu planned to attack Han.[32] When the Xiongnu invaded Taiyuan in 200 and were aided by the defector King Xin of Hán 韩 (not to be confused with the ruling dynasty of Hàn 漢), Emperor Gaozu personally led his forces through the snow to Pingcheng (near modern Datong, Shanxi).[33][34] What ensued was the Battle of Baideng, where Gaozu's forces were heavily surrounded for seven days; running short of supplies, he was forced to withdraw.[35][34]

After this defeat, the court adviser Liu Jing 劉敬 convinced the emperor to create a peace treaty and marriage alliance with the Xiongnu shanyu called the heqin 龢親 agreement.[36][37] Established in 198, the Han scheme behind the treaty was to corrupt the Xiongnu's nomadic values with Han luxury goods given as tribute (i.e. silks, wine, foodstuffs, etc.) and to make Modu Shanyu a son-in-law to Gaozu, thus making Modu's half-Chinese successor a subordinate to grandfather Gaozu (if the Xiongnu court could be effectively indoctrinated with Confucian familial values).[38] Instead, Modu Shanyu not only outlived Emperor Gaozu, but the treaty which acknowledged both rulers, shanyu and huangdi, as having equal status continued to vex the Han court until the 130s BCE.[39][40] Until then, the offering of princess brides and tributary items scarcely satisfied the Xiongnu, who often violated the 162 BCE agreement of respecting Han borders at the Great Wall and raided Han's northern frontiers.[41][42] Although these raids in the frontiers were disruptive, interactions with the Xiongnu did provide indirect benefits for Han, such as the introduction from the west of a valuable new pack animal, the donkey.[43]

Empress Dowager's rule

Emperor Hui

When Emperor Gaozu personally led the campaign against a rebel and former King of Huainan in 195 BCE, he received an arrow wound which allegedly led to his death in the following year.[44] His heir apparent Liu Ying 劉盈 took the throne as Emperor Hui of Han (r. 195–188 BCE). Shortly afterwards Gaozu's widow Lü Zhi, now the empress dowager, had a potential claimant to the throne, Liu Ruyi, poisoned to death and his mother, the Consort Qi, brutally mutilated.[44] When the teenage Emperor Hui discovered the cruel acts committed by his mother, Loewe says that he "did not dare disobey her."[44]

Hui's brief reign saw the completion of the defensive city walls around the capital Chang'an by 190; these originally 12 m (40 ft) tall rammed earth ruins still stand today and form a rough rectangular ground plan (with some irregularities due to topography).[45][46] This urban construction project was completed by 150,000 conscript laborers.[45] The establishment of the capital's Western Market in 189 implied that an Eastern Market already existed.[47]

Emperor Hui's reign also saw the repeal of old Qin laws banning certain types of literature and a cautious approach to foreign policy, renewing the heqin agreement with the Xiongnu and acknowledging the independent sovereignty of the King of Donghai and the King of Nanyue.[48] However, after Hui's reign the court under Lü Zhi was not only unable to deal with a Xiongnu invasion of Longxi Commandery (in modern Gansu) in which 2,000 Han prisoners were taken, but it also instigated a conflict with Zhao Tuo, King of Nanyue, after imposing a ban on exporting iron and other trade items to his southern kingdom.[49] Proclaiming himself Emperor Wu of Nanyue 南越武帝 in 183 BCE, he launched an invasion into the Han Kingdom of Changsha in 181 BCE.[49] Zhao Tuo did not rescind his rival imperial title until the Han ambassador Lu Jia visited Nanyue's court during the reign of Emperor Wen.[50] A map discovered at Mawangdui (dated no later than 168 BCE) shows positions of Han military garrisons which were to attack Nanyue in 181.[51]

Regency and downfall of the Lü clan

Since Emperor Hui did not bare any children with his empress by the time of his death in 188 BCE, Lü Zhi, now grand empress dowager and regent, was able to choose his successor.[48] She first placed Emperor Qianshao of Han (r. 188–184 BCE) on the throne, but then removed him for another puppet ruler Emperor Houshao of Han (r. 184–180 BCE).[48][53] She not only issued imperial edicts during their reigns, but she also appointed members of her own clan as kings; others clan members became key officers in the military and officials in the bureaucracy.[54][55]

After her death in 180, it was revealed that the Lü clan plotted to overthrow the Liu family's dynasty,[56] prompting the kings of Chu, Huainan, and Dai to march against Chang'an.[49] The Lü clan was ousted from power and destroyed by this alliance.[49][56] Although the King of Qi had led the advance towards Chang'an, he was passed over to become emperor due to his mobilization of troops without permission from the central government and the consideration that his mother possessed the same ambitious attitude as Empress Lü.[57] Since the mother of Liu Heng 劉恆, King of Dai, was considered to have a noble character, he was chosen to be the successor and reigned as Emperor Wen of Han (r. 180–157 BCE).[57]

Reign of Wen and Jing

Reforms and policies

The Han Empire under Emperor Wen and his successor Emperor Jing (r. 157–141 BCE) witnessed greater economic and dynastic stability, while the central government assumed more power over the realm.[58] In an attempt to contrast itself from the harsh rule of Qin, the court under these rulers abolished legal punishments involving mutilation in 167 BCE, eight widespread amnesties were issued from 180 to 141 BCE, and the tax rate on a household's agricultural produce was reduced from one-fifteenth to one-thirtieth in 168 BCE (abolished altogether in the following year, but reinstated at the rate of one-thirtieth in 156 BCE).[59]

Government policies were influenced by the Huang-Lao 黃老 ideology given patronage to by Wen's wife the Empress Dou (d. 135 BCE), who was empress dowager during Jing's reign and grand empress dowager during the early reign of his successor Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BCE).[58][60] Huang-Lao, named after the mythical Yellow Emperor and the 6th century BCE philosopher Laozi, viewed the former as the founder of ordered civilization, unlike the Confucian canon's patronage given to Yao and Shun.[60] Combining political and cosmological theory, these imperial patrons of Huang-Lao sponsored the policy of "nonaction" or wuwei 無為 (a central concept of Laozi's Daodejing), which enshrined written laws and regulations as conforming with the dao 道 of nature; thus a ruler should interfere as little as possible if administrative and legal systems were to function smoothly.[61] The influence of Huang-Lao ideology on affairs of state became eclipsed, however, with the formal adoption of Confucianism during Wu's reign and the later view that Laozi, not the Yellow Emperor, was the originator of Daoist practices.[62][60]

From 179 to 143 BCE, the number of kingdoms were increased from eleven to twenty-five and the number of commanderies from nineteen to forty.[63] This was not the result of a large territorial expansion. Rather, it was the consequence of wayward kingdoms rebelling against imperial Han or failing to produce an heir, prompting the central government to significantly reduce them in size or abolish them in order to carve out new commanderies and kingdoms.[64]

Rebellion of Seven States

When Liu Xian 劉賢, heir to the throne of the Kingdom of Wu, once made an official visit to the capital during Wen's reign, he played a board game called liubo with then crown prince Liu Qi 劉啟, the future Emperor Jing.[65] During a heated dispute over the divination portents of the game, the two men engaged in a physical fight which resulted in the death of Liu Xian.[65] This outraged his father Liu Pi 劉濞, the King of Wu, who was nonetheless obliged to claim allegiance to Liu Qi once he took the throne as Emperor Jing.[65]

Still bitter over the death of his son, the King of Wu led a revolt against Han in 154 BCE at the head of six other rebelling kingdoms: Chu, Zhao, Jiaoxi, Jiaodong, Zaichuan, and Jinan.[65] However, Han forces were ready and able to put down the revolt, destroying the coalition of seven states against Han.[65] The Kingdom of Wu was renamed as Jiangdu and given a new line or rulers.[66] The kingdoms of Jiaoxi, Jiaodong, Zaichuan, and Jinan were abolished, while Qi, Zhao, and Chu were significantly reduced in size.[66] Weighing in the threat that these semi-autonomous kingdoms posed to Han's imperial rule, Emperor Jing issued an edict in 145 BCE which outlawed the independent administrative staffs in the kingdoms and abolished all their senior offices except for the chancellor, who was henceforth reduced in status and appointed directly by the central government.[67] His successor Emperor Wu would diminish their power even further by abolishing the kingdoms' tradition of primogeniture and ordering that each king had to divide up his realm between all of his male heirs.[68]

Relations with the Xiongnu

The Han court received reports in 177 BCE that the Xiongnu Wise King of the Right had raided the non-Chinese tribes living under Han protection behind the Great Wall in the northwest (modern Gansu).[69] In the following year Modu Shanyu sent a letter to Emperor Wen informing him that the Wise King, allegedly insulted by Han officials, acted without the shanyu's permission and so he punished the Wise King by forcing him to conduct a military campaign against the nomadic Yuezhi.[69] Yet this event was merely part of a larger effort to recruit nomadic tribes north of Han China, during which the bulk of the Yuezhi were expelled from the Hexi Corridor (fleeing west into Central Asia) and the sedentary state of Loulan in the Lop Nur salt marsh, the nomadic Wusun of the Tian Shan range, and twenty-six other states east of Samarkand were conquered.[69][70][71] Modu Shanyu's threat that he would invade China if the heqin agreement was not renewed sparked a debate at the capital; although prominent ministers such as Jia Yi (d. 169 BCE) and Chao Cuo (d. 154 BCE) wanted to reject the heqin policy, Emperor Wen favored renewal of the agreement.[72] Modu Shanyu died before the Han tribute reached him, but his successor Laoshang Shanyu (174–160 BCE) renewed the heqin agreement and also negotiated the opening of border markets along Han China's borders.[73][74] Lifting the ban on contraband trade significantly reduced the frequency and size of Xiongnu raids into Han territory, which had necessitated Han armies of tens of thousands to be sent north.[75][76] However, continued Xiongnu raids by Laoshang Shanyu and his successor Junchen Shanyu (r. 160–126 BCE) reveal that the Xiongnu continued to violate Han's territorial sovereignty and thus did not respect the treaty.[74] While Laoshang Shanyu continued the conquest of his father by driving the Yuezhi into the Ili River valley, the Han quietly built up its strength in cavalry forces to later challenge the Xiongnu.[74][77]

Reign of Wu

Confucianism and government recruitment

Although Emperor Gaozu did not ascribe to the philosophy and system of ethics attributed to Kongzi 孔子 or Confucius (fl. 6th century BCE), he did enlist the aid of early Confucians such as Lu Jia and Shusun Tong 叔孫通; in 196 BCE he issued an edict which established the first Han regulation for recruiting men or merit into government service, which Robert P. Kramer calls the "first major impulse toward the famous examination system."[78] Emperors Wen and Jing had appointed Confucian academicians 博士 to court, yet not all academicians at their courts specialized in what would later become orthodox Confucian texts.[78] For several years after Liu Che 劉徹 took the throne as Emperor Wu in 141 BCE, the Grand Empress Dowager Dou dominated the court and did not accept any policy which she found unfavorable or contradicted Huang-Lao ideology.[78] After her death in 135 BCE, a major shift occurred in Chinese political history.

After Emperor Wu called for the submission of memorial essays to the throne on how to improve the government, he favored that of the official Dong Zhongshu (179–104 BCE), a philosopher who Kramers calls the first Confucian "theologian".[79] Dong's synthesis fused together the ethical ideas of Confucius with the cosmological beliefs in yin and yang 陰陽 and Five Elements or Wuxing 五行 by fitting them into the same holistic, universal system which governed heaven, earth, and the world of man.[80] Moreover, it justified the imperial system of government by providing it its place within the greater cosmos.[81] Reflecting the ideas of Dong Zhongshu, Emperor Wu issued an edict in 136 BCE that abolished the academic chairs other than those focused on the Five Classics: the Classic of Poetry 詩經, the Classic of Changes 易經, the Classic of Rites 禮記, the Classic of History 書經, and the Spring and Autumn Annals 春秋.[82] In 124 BCE Emperor Wu established the Imperial University, which had academicians teaching then only fifty pupils who took examinations; this was the incipient beginning of the civil service examination system refined in later dynasties.[82] Although sons and relatives of officials were often privileged with nominations to office, those who did not come from a family of officials were not barred from entry into the bureaucracy.[83] Rather, education in the Five Classics became the paramount prerequisite for gaining office; as a result, the Imperial University was expanded dramatically by the 2nd century CE when it accomodated thirty-thousand students.[84] With Cai Lun's (d. 121 CE) invention of the papermaking process in 105 CE,[85] the spread of paper as a cheap writing medium from the Eastern Han period onwards increased the supply of books and hence the amount of those who could be educated for civil service.[86]

War against the Xiongnu

The death of Empress Dou also marked a significant shift in foreign policy.[87] In order to address the Xiongnu threat and renewal of the heqin agreement, Emperor Wu called a court conference into session in 135 BCE where two factions of leading ministers debated the merits and faults of the current policy; Emperor Wu followed the majority consensus of his ministers that peace should be maintained.[76][88] A year later, while the Xiongnu were busy raiding the northern border and waiting for Han's response, Wu called another court conference into session. This time the faction calling for action against the Xiongnu was able to sway the majority opinion by making a compromise for those worried about stretching financial resources on an indefinite war campaign: in a limited engagement along the border near Mayi, the Han court plotted to lure Junchen Shanyu over with gifts and promises of defections in order to quickly eliminate him and cause political chaos in the Xiongnu Confederation.[89][88] When this assassination attempt failed in 133 BCE (Junchen Shanyu realized he had fallen into a trap and fled back north), the era of heqin-style appeasement was broken and the Han court thus resolved to engage in full-scale war.[88][90][91]

Leading campaigns involving tens of thousands of troops, in 127 BCE the Han general Wei Qing (d. 106 BCE) recaptured the Ordos Desert region from the Xiongnu and in 121 BCE Huo Qubing (d. 117 BCE) expelled them from the Qilian Mountains, gaining the surrender of many Xiongnu aristocrats including the Wise King of the Right.[92][93] At the Battle of Mobei in 119 BCE, generals Wei and Huo led the campaign into Mongolia (south of the Khangai Mountains) where they forced the Xiongnu leader to flee north of the Gobi Desert.[92][94] The maintenance of three-hundred thousand horses by government slaves in thirty-six different pasture lands was still not enough to satisfy the cavalry and baggage trains needed for these campaigns, so the government offered exemption from military and corvée labor for up to three male members of each household who presented a privately-bred horse to the government.[95]

Expansion, colonization, and the Silk Road

After the Xiongnu's Wise King of the Right, Hunye, surrendered to Huo Qubing in 121 BCE, the Han acquired a territory stretching from the Hexi Corridor to Lop Nur, thus cutting the Xiongnu off from their Qiang allies and paving the way towards the Tarim Basin of Central Asia (modern Xinjiang).[96][97][98] Not only were new commanderies established in the Ordos, but in the Hexi Corridor the four commanderies of Jiuquan, Zhangyi, Dunhuang, and Wuwei were established and successfully populated with Han settlers once a major Qiang-Xiongnu allied force was repelled from the region in 111 BCE.[96][99] In all, Emperor Wu's forces conquered roughly 4.4 million km2 (1.7 million mi2) of new land, by far the largest territorial expansion in Chinese history.[100] Many self-sustaining agricultural garrisons were established in these frontier outposts, which were used not only to support military campaigns but also to secure a trade route leading into Central Asia, the eastern terminus of the Silk Road.[101] After the heqin agreement broke down, the Xiongnu were forced to extact more crafts and agricultural foodstuffs from the subjugated Tarim Basin urban centers.[102] However, from 115 to 60 BCE the Han and Xiongnu battled for control and influence over these states,[103] while the Han encroachments from 108 to 101 BCE gained the tributary submission of Loulan, Turfan, Bügür, Dayuan (Fergana), and Kangju (Sogdiana).[104][105] The farthest-reaching and most expensive invasion was Li Guangli's 李廣利 four-year campaign against Fergana in the Syr Darya and Amu Darya river valleys.[105] Fergana threatened to cut off Han's access to the Silk Road, yet historian Sima Qian (d. 86 BCE) saved face by asserting that Li's mission was really a means to punish Dayuan for not handing over tribute of prized Central Asian stallions.[106]

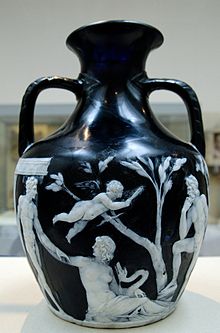

The westward travels of the Han diplomat Zhang Qian starting in 139 BCE was an unsuccessful attempt to secure an alliance with the Da Yuezhi (who were previously evicted from Gansu by the Xiongnu in 177 BCE); however, it revealed entire civilizations which the Chinese were unaware of until Wu's reign.[107][108][109] When Zhang returned in 125 BCE, he reported his visits to Dayuan (Fergana), Kangju (Sogdiana), and Daxia (Bactria, formerly the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom which was subjugated by the Da Yuezhi).[110] He described Dayuan and Daxia as settled and urban countries like China, and although he did not venture there, described Shendu (Indus River valley of North India) and Anxi (the Persian empire of Parthia) further west.[111] He even mentioned the silver coins used by the merchants of Parthia that were minted with the face of their ruler.[112] Envoys sent to these states returned with foreign delegations and lucrative trade caravans;[113] yet even before this, Zhang noted that these countries were importing Chinese silk.[112] After interrogating merchants, Zhang also discovered a southwestern trade route leading through Burma and on to India.[114] The earliest known Roman glassware found in China (but manufactured in the Roman Empire) is a glass bowl found in a Guangzhou tomb dating to the early 1st century BCE (latter half of Wu's reign) and perhaps came from a maritime route passing through the South China Sea.[115] Likewise, imported Chinese silk attire became popular in the Roman Empire by the time of Julius Caesar (100–44 BCE).[116]

Emperor Wu assisted King Wen of Nanyue in fending off an attack by Minyue (in modern Fujian) in 135 BCE.[117] After a pro-Han faction was overthrown at the court of Nanyue, Emperor Wu's naval forces invaded and quelled the southwestern kingdom in 111 BCE, bringing areas of modern Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan Island, and northern Vietnam under Han control.[118] Emepror Wu also launched an invasion into the Dian Kingdom of Yunnan in 109 BCE, subjugating its king as a tributary vassal, while later Dian rebellions in 86 BCE and 83 BCE, 14 CE (during Wang Mang's rule), and 42–5 CE were quelled by Han forces.[119] Emperor Wu sent an expedition into what is now North Korea in 128 BCE, but this was abandoned two years later.[120] In 108 BCE, another expedition established four commanderies there, only two of which (i.e. Xuantu Commandery and Lelang Commandery) remained after 82 BCE.[121] Although there was some violent resistance in 108 BCE and irregular raids by Goguryeo and Buyeo afterwards, the Chinese settlers conducted peaceful trade relations with native Koreans who lived largely independent of (but were influenced by) the sparse Han settlements.[122]

Economic reforms

In order to fund his prolonged military campaigns and far-flung colonization efforts, Emperor Wu turned away from the "nonaction" policy of earlier reigns by having the central government commandeer originally private industries and trades of salt mining and iron manufacturing by 117 BCE.[123][124] Another government monopoly over liquor was established in 98 BCE, but the majority consensus at a court conference in 81 BCE led to this monopoly being repealed.[125] The mathematician and technocratic official Sang Hongyang (d. 80 BCE), one of many former merchants drafted into the government to help administer these monopolies, was responsible for the 'equable transportation' system that eliminated price variation over time from place to place.[126] Moreover, it was a government means to take over the profitable grain trade and eliminate speculation in grain trading.[127] This along with the monopolies were criticized even during Wu's reign as bringing unnecessary hardships for merchants' profits and farmers forced to rely on poor-quality government-made goods and services; the monopolies and equable transportation did not last into the Eastern Han Era (25–220 CE).[128][129]

During Emperor Wu's reign, the poll tax for each minor aged three to fourteen was raised from 20 to 23 coins; the rate for adults remained at 120.[130] New taxes exacted on market transactions, wheeled vehicles, and properties were meant to bolster the growing military budget.[130] In 119 BCE a new copper coin weighing five shu 五銖 (3.2 g/0.11 oz)—replacing the four shu coin—was issued by the government (remaining the standard coin of China until the Tang Dynasty), followed by a ban on private minting in 113 BCE.[130][131] Earlier attempts to ban private minting took place in 186 and 144 BCE, but Wu's monopoly over the issue of coinage remained in place throughout the Han (although its stewardship changed hands from different government agencies).[132] From 118 BCE to 5 CE, the Han government minted 28,000,000,000 coins, an average of 220,000,000 coins a year.[133]

Latter half of Western Han

Regency of Huo Guang

Emperor Wu's first wife, Empress Chen Jiao, was stripped of her status in 130 BCE after allegations that her daughter attempted witchcraft to help her produce a male heir.[136] In 91 BCE the Consort Li, sister of general Li Guangli, levelled similar allegations of witchcraft against the family of Wu's second wife Empress Wei Zifu in an attempt to oust them from power.[137][138] While Emperor Wu was away at his quiet summer retreat of Ganquan 甘泉 (in Xianyang, Shaanxi province), five days of battle erupted within the capital between the Wei clan, led by the crown prince Liu Ju, and the rival Li clan.[137] The Empress, the crown prince, the Wei clan and many of their followers were killed, yet the Li clan fell from grace as well when Li Guangli surrendered in battle to the Xiongnu a year later.[138][139]

The official Huo Guang (d. 168 BCE), related to Empress Wei by marriage, was the only prominent member of the Wei faction not killed in this conflict.[138][139] Due to his good reputation, Huo Guang was even entrusted by Wu to form a triumvirate regency alongside Jin Midi (d. 86 BCE) and Shangguan Jie 上官桀 over the court of his successor, the child Liu Fuling 劉弗陵 who reigned as Emperor Zhao of Han (r. 87–74 BCE).[139] Jin Midi died a year later and by 80 BCE Shangguan Jie and Sang Hongyang (now Imperial Secretary 御史大夫) were executed when they were indicated as conspirators in a plot by the King of Yan to take the throne; this gave Huo unrivaled power.[140][141] However, he did not abuse his power in the eyes of the Confucian establishment and gained popularity for reducing Emperor Wu's taxes.[142]

Emperor Zhao died in 74 BCE without a successor, while the one chosen to replace him on July 18, Prince He of Changyi, was removed on August 14 after displaying a lack of character or capacity to rule.[140][143] His impeachment was secured with a petition signed by all the leading ministers and submitted to Grand Empress Dowager Shangguan for approval.[143] Liu Bingyi 病已劉, a grandson of Crown Prince Liu Ju, was named Emperor Xuan of Han (74–49 BCE) on September 10.[144] Huo Guang remained in power as regent (officially the General-in-Chief 大將軍) over Emperor Xuan until he died of natural causes in 68 BCE.[145][146] Yet in 66 BCE the Huo clan was charged with conspiracy against the throne and eliminated.[145] This was the culmination of Emperor Xuan's revenge after Huo Guang's wife had poisoned his beloved Empress Xu Pingjun in 71 BCE only to have her replaced by Huo Guang's daughter Empress Huo Chengjun (the latter was deposed in September 66 BCE).[147] Liu Shi 劉奭, son of Empress Xu, succeeded his father as Emperor Yuan of Han (49–33 BCE).[147]

Reforms and frugality

During Emperor Wu's reign and Huo Guang's regency, the dominant political faction was the Modernist Party. This party favored government monopolies over salt and iron, greater government intervention in the private economy, aggressive foreign policy, territorial expansion, and the Qin Dynasty approach to discipline by meting out more punishments for faults and less rewards for service.[148] After Huo Guang's regency, the Reformist Party gained more leverage over state affiars and policy decisions.[148] This party favored the abolishment of government monopolies, limited government intervention in the private economy, a moderate foreign policy, limited colonization efforts, frugal budget reform, and a return to the Zhou Dynasty ideal of granting more rewards for service to display the dynasty's magnanimity.[149] This party's influence can be seen in the abolition of the central government's salt and iron monopolies in 44 BCE, yet these were reinstated in 41 BCE, only to be abolished again during the 1st century CE and transferred to local administrations (and perhaps also private entrepreneurship).[150] By 66 BCE the Reformists had many of the lavish spectacles, games, and entertainments installed by Emperor Wu to impress foriegn dignitaries cancelled on the grounds that they were excessive and ostentatious.[151]

Spurred by alleged signs from Heaven warning the ruler of his incompetence, a total of eighteen general amnesties were granted during the combined reigns of Emperor Yuan and Emperor Cheng of Han (r. 33–7 BCE).[152] Emperor Yuan reduced the severity of punishment for several crimes, while Cheng reduced the length of judicial procedures in 34 BCE since they were disrupting the lives of commoners.[152] While the Modernists had accepted sums of cash from criminals to have their sentences commuted or even dropped, the Reformists reversed this policy since it favored the wealthy over the poor and was not an effective deterrent against crime.[153]

Emperor Cheng made major reforms to state-sponsored religion. The Qin Dynasty had worshipped four main legendary deities, with another added by Liu Bang in 205 BCE; these were the Five Powers, or Wudi 五帝.[154] In 31 BCE Emperor Cheng, in an effort to gain Heaven's favor and bless him with a male heir, halted all ceremonies dedicated to the Five Powers and replaced them with ceremonies for the supreme god Shangdi, who the kings of Zhou had worshipped.[154][155]

Foreign relations and war

The first half of the 1st century BCE witnessed several succession crises for the Xiongnu leadership, allowing Han to further cement its control over the Western Regions.[156][157] The Han general Fu Jiezi had the pro-Xiongnu King of Loulan assassinated in 77 BCE.[158] The Han formed a coalition with the Wusun, Dingling, and Wuhuan peoples in 72 BCE; their combined forces inflicted a major defeat against the Xiongnu.[159] The Han regained its influence over the Turfan Depression after defeating the Xiongnu at the Battle of Jushi in 67 BCE.[159] In 65 BCE Han was able to install a new King of Kucha (a state north of the Taklamakan Desert) who would be agreeable to Han interests in the region.[160] The office of the Protectorate of the Western Regions, first commanded by Zheng Ji (d. 49 BCE), was established in 60 BCE to supervise colonial activities and conduct relations with the small kingdoms of the Tarim Basin.[159][161]

After Zhizhi Shanyu (r. 56–36 BCE) had inflicted a serious defeat against his rival brother and royal contendor Huhanye Shanyu 呼韓邪 (r. 58–31 BCE), the latter turned to the Han Empire for aid.[162] After Huhanye and his supporters debated whether or not to accept Han's terms that he become a vassal, Huhanye finally sent his son as a hostage prince to Han and came in person to the Han court during the Chinese New Year celebration to pay homage and tribute.[163] While the Modernist officials wanted to treat this Xiongnu leader as a hostile enemy lower than a Han king, the Reformists at court were able to determine the seating arrangements, making Huhanye a distinguished guest of honor with rich rewards of 5 kg (11 lbs) of gold, 200,000 cash coins, 77 suits of clothes, 8,000 bales of silk fabric, 1,500 kg (3,306 lbs) of silk floss, and 15 horses, in addition to 680,000 L (179,636 gallons) of grain sent to him when he returned home.[164][165]

Huhanye Shanyu and his successors were encouraged to pay further trips of homage to the Han court due to the increasing amount of gifts showered on them after each visit; this was a cause for complaint by some ministers in 3 BCE, yet the financial consequence of pampering their vassal was deemed superior to the heqin agreement.[166] Zhizhi Shanyu even attempted to send hostages and tribute to the Han court in hopes to enter their tributary system, but the Han General Chen Tang and Protector General Gan Yanshou 甘延寿, acting without explicit permission from the Han court, allied with Kangju (Sogdiana) and had Zhizhi killed at the Battle of Zhizhi (in modern Taraz, Kazakhstan) in 36 BCE.[167][168] The Reformist Han court, reluctant to award independent missions let alone foreign interventionism, gave Chen and Gan only modest rewards.[167][168] Despite the show of favor with lavish gifts, Huhanye was unable to secure a royal marriage alliance with Han; instead of a princess, he settled for the Lady Wang Zhaojun, one of the Four Beauties of ancient China.[169] This marked a departure from the earlier heqin agreement, where a Chinese princess was handed over to the shanyu as his bride.[169]

Wang Mang's usurpation

Wang Mang seizes control

The long life of Empress Wang Zhengjun (71 BCE – 13 CE), wife of Emperor Yuan and mother to Emperor Cheng, ensured that her male relatives would be appointed one after another to the role of regent, officially known as Grand Commandant.[170][171] Emperor Cheng, who was more interested in cockfighting and chasing after beautiful women than administering the empire, left much of the affairs of state to his relatives of the Wang clan.[170][172] On November 28, 8 BCE Wang Mang (45 BCE – 23 CE), a nephew of Empress Dowager Wang, became the new Grand Commandant.[170] However, when Emperor Ai of Han (r. 7–1 BCE) took the throne, the Ding clan of his mother and Fu clan of his grandmother conspired against the Wang clan and forced Wang Mang to resign on August 27, 7 BCE, followed by his forced departure from the capital to his marquisate in 5 BCE.[173]

Due to pressure from Wang's supporters, Emperor Ai invited Wang Mang back to the capital in 2 BCE.[174] A year later Emperor Ai died of illness without a son or heir, while Wang Mang was reinstated as regent over Emperor Ping of Han (r. 1–6 BCE), a first cousin of the former emperor.[174] Although Wang had married his daughter to Emperor Ping, the latter was still a child when he died in 6 CE.[175] In July of that year, Grand Empress Dowager Wang confirmed Wang Mang as acting emperor and the child Liu Ying as his heir to succeed him, despite the fact that a Liu family marquis made a revolt against Wang a month earlier, followed by others.[176] However, these rebellions were quelled and Wang Mang promised to hand over power to Liu Ying when he reached his majority.[176] Despite promises to relinquish power, Wang initiated a campaign of propaganda to show that Heaven was sending signals that it was time for Han's rule to end.[177][178] On January 10, 9 CE he announced that Han had run its course and accepted the requests that he proclaim himself emperor of the Xin Dynasty (9–23 CE).[177][178][179]

Traditionalist reforms

Wang Mang had a grand vision to restore China to a fabled golden age achieved in the early Zhou Dynasty, the era which Confucius had idealized.[180][181] He attempted sweeping reforms, including the outlawing of slavery in 9 CE and institution of the King's Fields 王田 system in 14 CE which outlawed the purchase and selling of land and allotted a standard amount of land to each family.[180][182][181] However, not only did slaves make up a tiny proportion of the population, but slavery was reestablished in 12 CE along with the cancellation of his land reform in the same year due to widespread protest.[181][183]

As Hans Bielenstein points out, the partisan historian Ban Gu (32–92 CE) wrote that Wang's reforms led to his downfall, yet aside from slavery and land reform, much of Wang's reforms were in line with earlier Han policies.[184] Although his new denominations of currency introduced in 7, 9, 10, and 14 CE debased the value of coinage, earlier introductions of lighter-weight currencies resulted in marginal economic damage.[184] He renamed all the commanderies of the empire as well as bureaucratic titles, yet there were precedents for this as well.[185] His monopoly on fermented liquor established in 10 CE had also existed in the Western Han Era.[186] The government monopolies were rescinded in 22 CE because they could no longer be enforced during a large-scale rebellion against him; yet this was not as a result of his policies, but rather the massive flooding of the Yellow River which caused widespread chaos and disruption.[183][187]

Foreign relations under Wang

The half-Chinese, half-Xiongnu noble Yituzhiyashi 伊屠智牙師, son of Huhanye Shanyu and Wang Zhaojun, became a vocal partisan for Han China within the Xiongnu realm, leading conservative Xiongnu nobles to anticipate a break in the alliance with Han.[188] The moment came when Wang Mang assumed the throne and demoted the shanyu to a lesser rank; this became a pretext for war.[189] During the winter of 10 to 11 CE, Wang amassed 300,000 troops along the northern border of Han China, a show of force which led the Xiongnu to back down.[189] Yet when raiding continued, Wang Mang had the princely Xiongnu hostage held by Han authorities executed.[189] Diplomatic relations were repaired when Xian (r. 13–18) became the shanyu, only to be soiled again when Huduershi Shanyu 呼都而尸 (r. 18–48 AD) took the throne and raided Han's borders in 19 CE.[190] Wang Mang was able to negotiate the release of three thousand Wuhuan prisoners held by the Xiongnu and thus strengthen the bond between Wuhuan and Han.[191] However, relations were cut off when the Wuhuan peoples abandoned their garrison assigned to them in Dai Commandery; Wang retaliated by killing the Wuhuan hostages sent to Han.[191]

The Tarim Basin kingdom of Yanqi (Karasahr, located east of Kucha, west of Turfan) rebelled against Han authority in 13 CE, killing Han's Protector General Dan Qin 但欽.[192] Wang Mang sent a force to retaliate against Karasahr in 16 CE, quelling their resistance and ensuring that the region would remain under Chinese control until the widespread rebellion against Wang Mang toppled his rule in 23 CE.[192] Wang also extended Chinese influence over Tibetan tribes in the Kokonor region and fended off an attack in 12 CE by Goguryeo (an early Korean state located around the Yalu River) in the Korean peninsula.[193][194] However, as the widespread rebellion within China mounted from 20 to 23 CE, the Koreans raided Lelang Commandery and Han did not reassert itself in the region until 30 CE.[194]

Restoration of the Han

Natural disaster and civil war

Before 3 CE, the course of the Yellow River had emptied into the Bohai Sea at Tianjin, but the gradual build up of silt in its riverbed—which raised the water level each year—overpowered the dikes built to prevent flooding and the river split in two, with one arm flowing south of the Shandong Peninsula and into the East China Sea.[195][196][197] A second flood in 11 CE caused the river to empty north of the Shandong Peninsula once more, although it would never again empty as far north as Tianjin.[195][198] On April 8, 70 CE, a Han imperial edict boasted that the southern branch of the Yellow River emptying south of the Shandong Peninsula was finally cut off by Han engineering.[199] With much of the southern North China Plain inundated, thousands of starving peasants who were displaced from their homes formed groups of bandits and rebels, most notably the Red Eyebrows.[195][197][200] Wang Mang's armies tried to quell these rebellions in 18 and 22 CE, but these attempts ended in failure and with the death of his commanders.[197][200]

Liu Yan (d. 23 CE), a descendant of Emperor Cheng, led a group of rebelling gentry groups from Nanyang who had Yan's third cousin Liu Xuan 劉玄 accept the title Emperor Gengshi of Han (r. 23–25) on March 11, 23 CE.[201][202] Lieutenant General Liu Xiu 劉秀, a brother of Liu Yan and future Emperor Guangwu of Han (r. 25–57 CE), distinguished himself at the Battle of Kunyang on July 7, 23 CE when he relieved a city under siege by Wang Mang's forces and turned the tide of the war.[203][204] Soon afterwards, Emperor Gengshi had Liu Yan executed on grounds of treason and Liu Xiu, fearing for his life, resigned from office as Minister of Ceremonies and avoided public mourning for his brother; for this, the emperor gave Liu Xiu a marquisate and a promotion as general.[203]

A revolt of local insurgents claiming loyalty to Han broke out in the capital. From October 4–6 Wang Mang made a last stand at the Weiyang Palace only to be killed and decapitated; his head was sent to Gengshi's headquarters at Wan before Han armies even reached Chang'an on October 9.[205][206] Emperor Gengshi settled Luoyang as his new capital where he invited Red Eyebrows leader Fan Chong 樊崇 to stay, yet Gengshi granted him only honorary titles, so Fan decided to flee once his men began to desert him.[207][208] Gengshi moved the capital back to Chang'an in 24 CE, yet in the following year the Red Eyebrows defeated his forces, appointed their own puppet ruler Liu Penzi, entered Chang'an and captured the fleeing Gengshi who they demoted as King of Changsha before killing him.[209][210]

Reconsolidation under Guangwu

While acting as a commissioner under Emperor Gengshi north of the Yellow River, Liu Xiu gathered a significant following after putting down a local rebellion (in what is now Hebei province).[211] He took the throne as Emperor Guangwu on August 5, 25 CE and occupied Luoyang as his capital on November 5, yet by this point there were eleven others in China claiming the title of emperor.[212][213] With the efforts of his officers Deng Yu and Feng Yi, Guangwu forced the wandering Red Eyebrows into surrender by March 15, 27 CE, resettling them at Luoyang, yet had their leader Fan Chong executed when a plot of rebellion was revealed.[214][215]

From 26 to 30 CE, Guangwu defeated various warlords and conquered the Central Plain and Shandong Peninsula in the east.[216][217] Allying with the warlord Dou Rong 竇融 of the distant Hexi Corridor in 29, Guangwu nearly defeated the Gansu warlord Wei Ao 隗嚣 in 32, yet the latter died in 33 and Guangwu took over his remnant forces the following year.[217][218] The only great adversary left standing was Gongsun Shu 公孫述, whose base was at Chengdu of modern Sichuan province.[217][219] Although Guangwu's forces successfully burned down Gongsun's fortified pontoon bridge stretching across the Yangzi River,[220] Guangwu's commanding general Cen Peng 岑彭 was killed in 35 by an assassin sent by Gongsun Shu.[221] Nevertheless, Han General Wu Han (d. 44 CE) resumed Cen's campaign along the Yangzi and Min rivers and destroyed Gongsun's forces by December 36 CE.[220][222]

Since Chang'an is located west of Luoyang, the era names Western Han (202 BCE – 9 CE) and Eastern Han (25–220 CE) are accepted by historians.[223] Although Guangwu's new capital at Luoyang only had a walled area of 10 km2 (3.91 mi2), the total size of the city outside the walls stretched for 24.5 km2 (9.4 mi2), meaning that only Chang'an and Rome outranked it in size during ancient times.[224] It's 10 m (32 ft) tall eastern, western, and northern walls still stand today, although the southern wall was washed away when the Luo River changed its course.[225][226] Within its walls it had two prominent palaces, both of which existed during Western Han, but were expanded by Guangwu and his successors.[227] While Eastern Han Luoyang is estimated to have held roughly five-hundred thousand inhabitants,[224] the first known census data for the whole of China, dated 2 CE, recorded a population of fifty-eight million.[228] Comparing this to the census of 140 CE, there was a significant migratory shift of up to ten million people from northern to southern China during the course of Eastern Han, largely because of natural disasters and wars with nomadic groups in the north.[229]

Policies under Guangwu, Ming, Zhang, and He

Scrapping Wang Mang's denominations of currency, Emperor Guangwu reintroduced Western Han's standard five shu coin in 40 CE.[230] Making up for lost revenue after the central government's salt and iron monopolies were cancelled, private manufacturers were more heavily taxed while the government even purchased its armies' swords and shields from private businesses.[230] Guangwu eliminated the military post of commandant in each commandery by 30 CE, from that point on having the commanderies' civil administrators oversee local martial affairs.[231] In 31 CE he also eliminated the Western Han system of compulsory conscription of peasants into the armed forces for a year of training and year of service (as either infantryman, cavalryman, or naval marine); instead he built a volunteer force which lasted throughout Eastern Han.[232] Like his military subsitution tax,[232] he also allowed peasants to avoid the one-month corvée duty with a commutable tax as hired labor became more popular.[233] After Wang Mang had demoted all marquises to commoner status, Guangwu made an effort from 27 onwards to find their relatives and restore the abolished marquisates.[234] He restored the kingdoms, yet by 37 CE he had all the kings reduced to the status of marquises and then had his sons reduced to dukes in 39 CE.[235] He reversed this decision in 41 CE when he elevated his sons back to the status of kings and his nephews from dukes to kings in 43, which Bielenstein calls a "retrograde" step for Eastern Han.[236]

Emperor Ming of Han (r. 57–75, Liu Yang 劉陽), like the Western Han and Wang Mang before him, established a price stabilization system where the government bought grain when cheap and sold it to the public when private commercial prices were high due to limited stocks.[237] He also reestablished the Office for Price Adjustment and Stabilization that had been abolished by Guangwu, thus favoring centralizing policies which were not the hallmark of most Eastern Han policies to come.[237] In fact, Emperor Ming cancelled these schemes by 68 when convinced that government hoarding of grain actually raised its price and enriched the already powerful landowning class.[237] With the renewed economic prosperity brought about by his father's reign, Emperor Ming was able to address the problem of flooding along the Yellow River by funding repair efforts for various dams and canals.[238] A patron of scholarship, Emperor Ming also established a school for young nobles aside from the Imperial University.[239]

Emperor Zhang of Han (r. 75–88, Liu Da 劉炟) faced an agrarian crisis in his early reign when a cattle epidemic broke out in 76.[240] In addition to providing disaster relief, Zhang also made reforms to legal procedures and lightened existing punishments with the bastinado, since he believed that this would restore the seasonal balance of yin and yang and cure the epidemic.[240] In other shows of imperial benevolence, in 78 he ceased the corvée work on the canal works of the Hutuo River running through the Taihang Mountains since it was considered too much of a hardship on the people; in 85 he granted a three-year poll tax exemption for any woman who gave birth and exempted their husbands for a year.[240] Unlike other Eastern Han rulers who sponsored the New Texts 今文經 tradition of the Confucian Five Classics, Zhang was a patron of the Old Texts 古文经 tradition and held scholarly debates on the validity of either school.[241] Rafe de Crespigny writes that the major reform of the Eastern Han period was Zhang's reintroduction in 85 CE of an amended Sifen 四分 calendar, replacing Emperor Wu's Taichu 太初 calendar of 104 BCE which had become inaccurate over two centuries (the former measured the tropical year at 365.25 days like the Julian Calendar, while the latter measured the tropical year at 365 days and the lunar month at 29 days).[241][242]

Emperor He of Han (r. 88–105, Liu Zhao 劉肇) was tolerant of both New Text and Old Text traditions, though orthodox studies were in decline and works skeptical of New Texts, such as Wang Chong's (27 – c. 100 CE) Lunheng, disillusioned the scholarly community with that tradition.[243] He also showed an interest in history when he commissioned the Lady Ban Zhao (45–116 CE) to use the imperial archives in order to complete the Book of Han, the work of her deceased father and brother.[243][244] This set an important precedent of imperial control over the recording of history and thus was unlike Sima Qian's far more independent work, the Records of the Grand Historian (109–91 BCE).[244] When plagues of locusts, floods, and earthquakes disrupted the lives of commoners, Emperor He's relief policies were to cut taxes, open granaries, provide government loans, forgive private debts, and resettle people away from disaster areas.[245] Believing that a severe drought in 94 was the cosmological result of injustice in the legal system, Emperor He personally inspected prisons and held jail delivery, finding that some had false charges levelled against them and so sent the Prefect of Luoyang to prison; rain allegedly came soon afterwards.[245] Considering the expenditures for his disaster relief programs, Emperor He also showed concern for fiscal constraint in 103 CE when he cancelled the courier service bringing lychee and longan fruits to the imperial dining table.[245]

Foreign relations and split of the Xiongnu realm

The Vietnamese Trưng Sisters (徵 Zheng) instigated a rebellion in the Red River Delta of Jiaozhi Commandery in 40 CE.[246][247] Guangwu sent the now eldery officer Ma Yuan (14 BCE – 49 CE) to crush their resistance in a campaign from 42 to 43 CE.[246][247] The two rebel sisters were defeated and killed, while their native Dong Son drums were melted down and recast into a large bronze horse statue presented to Guangwu at Luoyang.[246][247] Ma Yuan was also earlier responsible for quelling rebellions and incursions of Qiang and Di peoples, and in 44 CE he fended off an allied Xiongnu-Wuhuan attack.[247][248] However, Ma Yuan was deployed on no more major offensives in the north, since the Wuhuan and the Xianbei turned on their former Xiongnu allies.[248] By 49 CE, both the Xianbei and Wuhuan entered Han's tributary system.[249]

When Huduershi Shanyu had his son Punu 蒲奴 succeed him in 46 CE, thus breaking Huhanye's tradition of having a brother succeed to the throne, his nephew Bi 比 was outraged and in 48 CE was proclaimed a rival shanyu in his power base south of Punu's control.[250] This split created the Northern Xiongnu and Southern Xiongnu, and like Huhanye before him, Bi turned to the Han for aid in 50 CE.[250] When Bi came to pay homage to the Han court, he was given 10,000 bales of silk fabrics, 2,500 kg (5,500 lbs) of silk, 500,000 L (132,000 gallons) of rice, and 36,000 head of cattle.[250] Unlike in Huhanye's time, however, the Southern Xiongnu were overseen by a Han Prefect who not only acted as an arbiter in Xiongnu legal cases, but also monitored the movements of the shanyu and his followers who were settled in Han's northern commanderies in Shanxi, Gansu, and Inner Mongolia.[251] Northern Xiongnu attempts to enter Han's tributary system were rejected.[252]

Following Wang Mang's death, the Kingdom of Yarkand looked after the Chinese officials and families stranded in the Tarim Basin and fought the Xiongnu for control over it.[254] Emperor Guangwu, preoccupied with civil wars in China, simply granted the King Kang of Yarkand an official title in 29 CE and in 41 CE made his successor King Xian a Protector General; he gained Xian's ire, however, when he reduced the title to the honorary "Great General of Han".[254] Yarkand overtaxed its subjects of Khotan, Turfan, Kucha, and Karasahr, all of which decided to ally with the Northern Xiongnu.[254] By 61 CE Khotan had conquered Yarkand, yet this led to a civil war to decide which regional kingdom would be the next hegemon.[254] The Northern Xiongnu took advantage of the infighting, conquered the Tarim Basin once more, and used it as a base to stage raids into Han's Hexi Corridor by 63 CE.[254] In the same year, the Han court opened border markets for trade with the Northern Xiongnu in hopes to appease them.[255]

By 73 CE the Han was capable once more of contending with the Xiongnu over control of the Tarim Basin. At the Battle of Yiwulu in that year, Dou Gu (d. 88 CE) reached as far as Lake Barkol when he defeated a Northern Xiongnu king and established an agricultural garrison at Hami.[256] Although Dou Gu was able to evict the Xiongnu from Turfan in 74 CE, when the Han appointed Chen Mu (d. 75 CE) as the new Protector General of the Western Regions, the Northern Xiongnu invaded the Bogda Mountains and the people of Karasarh and Kucha killed Chen Mu and his troops.[257] The Han garrison at Hami was forced to withdraw in 77.[258] The next Han expedition against the Northern Xiongnu was led in 89 CE by Dou Xian (d. 92); at the Battle of Ikh Bayan, Dou's forces chased the Northern Shanyu into the Altai Mountains, allegedly killing 13,000 Xiongnu and accepting the surrender of 200,000 Xiongnu from 81 tribes.[258][259]

After Dou sent 2,000 cavalry to attack the Northern Xiongnu base at Hami, he was followed by the initiative of Ban Chao (d. 102 CE),[258] who earlier installed a new king of Kashgar as a Han ally.[260] When this king turned against him and enlisted the aid of Sogdiana in 84 CE, Ban Chao arranged an alliance with the Kushan Empire (of modern North India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan), which put political pressure on Sogdiana to back down; Ban later assassinated the King Zhong of Kashgar.[260] Since Kushan provided aid to Ban Chao in quelling Turfan and sent tribute and hostages to Han, its ruler Vima Takto (r. c. 80–90 CE) requested a Chinese princess bride; when this was rejected in 90 CE, Kushan marched 70,000 troops to Wakhan against Ban Chao.[261][262] Ban used scorched earth against them, forcing Kushan to request food supplies from Kucha, but the Kushan messengers were intercepted by Ban, forcing Kushan to withdraw.[261][262] In 91 CE, Ban Chao was formally recognized as the Protector General of the Western Regions, an office he filled until 101 CE and was later taken over by his son Ban Yong 班勇.[263] Tributary gifts and emissaries from Persian Parthia, then under Pacorus II of Parthia (r. 78–105 CE), came to the Han in 87, 89, and 101 CE bringing exotic animals such as ostriches and lions.[264] When Ban Chao dispatched his emissary Gan Ying in 97 CE to reach Daqin (the Roman Empire), the Parthians prevented him from traveling there and he did not reach farther than the Persian Gulf.[265][266] Elephants and rhinoceroses were also presented as gifts to the Han court in 94 and 97 by a king in what is now Burma.[243] The first known diplomatic mission from a ruler in Japan came in 57 CE (followed by another in 107); a golden seal of Emperor Guangwu's was even discovered in 1784 in Chikuzen Province.[267]

The first mentioning of Buddhism in China was made in 65 CE during Ming's reign, when the Chinese clearly associated it with Huang-Lao Daoism.[268] Emperor Ming had the first Buddhist temple of China—the White Horse Temple—built at Luoyang in honor of two foreign monks: Jiashemoteng 迦葉摩騰 (Kāśyapa Mātanga) and Zhu Falan 竺法蘭 (Dharmaratna the Indian).[269] These monks were alleged to have translated the Sutra of Forty-two Chapters from Sanskrit into Chinese, although it is now proven that this text was not translated into Chinese until the 2nd century CE.[269][270]

Court, kinsmen, and consort clans

Besides being pressured to divorce Empress Guo Shengtong in 41 CE to wed Empress Yin Lihua instead (since the latter was from a prominent family of Nanyang), there was little drama with imperial kinsmen at Guangwu's court, as Empress Guo continued to live peacefully in the Northern Palace 北宮 of Luoyang and her son, the former heir apparent, was demoted to the status of a king.[271] However, trouble with imperial kinsmen turned violent during Ming's reign. In addition to exiling his half-brother Liu Ying (d. 71, committed suicide) over conspiracies against the throne, Emperor Ming also targeted hundreds of others with similar charges (of using occult omens and witchcraft) resulting in exile, torture for gaining confessions, and execution.[236][272] This trend of persecution did not end until Emperor Zhang took the throne, who was for the most part generous towards his kingly brothers and called back many to the capital who had been exiled under Ming's rule.[273]

Of greater consequence for the dynasty, however, was Emperor He's coup of 92 CE in which eunuchs made their first significant involvement in court politics of Eastern Han.[274] Emperor Zhang had upheld a good relationship with his titular mother and Ming's widow, the humble Empress Dowager Ma (d. 79),[273] but Empress Dowager Dou (d. 97), the widow of Emperor Zhang, was overbearing towards Emperor He (son of Emperor Zhang and Consort Liang) in his early reign and, concealing the identity of his natural mother from him, raised He as her own after purging the Liang family from power.[275] In order to put He on the throne, Empress Dowager Dou had even demoted the crown prince Liu Qing (78–106) as a king and put his mother, Consort Song (d. 82), into a prison hospital where she poisoned herself.[276] Unwilling to yield his power any longer to the mighty Dou clan, Emperor He enlisted the aid of palace eunuchs led by Zheng Zhong (d. 107) to overthrow the Dou clan on charges of treason, stripping them of titles, exiling them, forcing many to commit suicide, and had the Empress Dowager placed under house arrest.[277][278]

Middle age of Eastern Han

Empress Deng Sui, consort families, and eunuchs

Empress Deng Sui (d. 121), widow to Emperor He, became empress dowager in 105 and thus had the final say in appointing He's successor (since he had appointed none); she placed his infant son Liu Long 劉隆 on the throne as Emperor Shang of Han (r. 105–106).[279][280] When the latter died at only age one, she placed another child Liu Hu 劉祜 on the throne as Emperor An of Han (r. 106–125).[280][281] With another unable ruler on the throne, Empress Deng Sui was the de facto ruler of China until her death, since her brother Deng Zhi's 鄧騭 brief occupation as the General-in-Chief 大將軍 from 109–110 did not in fact make him the ruling regent.[281][282] With her death on April 17, 121 CE, Emperor An accepted the charge of eunuchs Li Run 李閏 and Jiang Jing 江京 that she had plotted to overthrow him; on June 3 he charged the Deng clan with treason and had them dismissed from office, stripped of title, reduced to commoner status, exiled to remote areas, and drove many to commit suicide.[283][284]

The Yan clan of Empress Yan Ji (d. 126), wife of Emperor An, and the eunuchs Jiang Jing and Fan Feng 樊豐 pressured Emperor An to demote his nine-year-old heir apparent Liu Bao 劉保 to the status of a king on October 5, 124 CE on charges of conspiracy, despite protests from senior government officials.[285][286] When Emperor An died on April 30, 125 CE the Empress Dowager Yan was free to choose his successor, Liu Yi 劉懿 (grandson of Emperor Zhang), who reigned as Emperor Shao of Han.[285][286] After the child died suddenly in that same year (125), the eunuch Sun Cheng (d. 132) made a palace coup, slaughtering the opposing eunuchs, and thrust Liu Bao on the throne as Emperor Shun of Han (r. 125–144); Sun then put Empress Dowager Yan under house arrest, had her brothers killed, and the rest of her family exiled to Vietnam.[285][287]

Emperor Shun had no sons with Empress Liang Na (d. 150), yet when his son Liu Bing 劉炳 briefly took the throne as Emperor Chong of Han in 145, the mother of the latter, Consort Yu, was in no position of power to challenge now Empress Dowager Liang Na.[288][289] After the child Emperor Zhi of Han (r. 145–146) briefly sat on the throne, Empress Dowager Liang and her brother Liang Ji (d. 159), now regent General-in-Chief, decided that Liu Zhi 劉志 should take the throne as Emperor Huan of Han (r. 146–168).[288][289] When the Empress Dowager's sister, Empress Yixian, died in 159, Liang Ji attempted to gain the favor of the new Empress Deng Mengnü (d. 165), but when she resisted Liang Ji had her brother-in-law killed, prompting Emperor Huan to use eunuchs to oust Liang Ji from power; the latter committed suicide when his residence was surrounded by imperial guards.[290][291] Emperor Huan died with no official heir, so Empress Dou Miao (d. 172), now the empress dowager, had Liu Hong 劉宏 take the throne as Emperor Ling of Han (r. 168–189).[292][293]

Reforms and policies of middle Eastern Han

Natural disasters of flood, dought, earthquakes, and plagues of locusts already apparent in He's reign became even more severe when Empress Dowager Deng took over, causing a financial crisis as her government attempted various relief measures of tax remissions, donations to the poor, and immediate shipping of government grain to the most hard-hit areas.[295] Although some water control works were repaired in 115 and 116, many government projects became underfunded due to these relief efforts for natural disasters and the armed response to the large-scale Qiang people's rebellion of 107–118.[296] Aware of her financial constraints, the Empress Dowager limited the expenses at banquets, the fodder for imperial horses who weren't pulling carriages, and the amount of luxury goods manufactured by the imperial workshops.[295] She approved the suggestion of the Three Excellencies that she sell some civil offices and even secondary marquis ranks to collect more revenue; the sale of office was continued by Emperor Huan and became extremely corrupt during Emperor Ling's reign.[296]

Emperor An continued similar disaster relief programs that Empress Dowager Deng had implemented, though he reversed some of her decisions, such as a 116 CE edict requiring officials to leave office for three years of mourning after the death of a parent (an ideal Confucian more).[297] Since this seemed to contradict Confucian morals, Emperor An's sponsorship of renowned scholars was aimed at shoring up popularity among Confucians.[297] Xu Shen (58–147), although an Old Text scholar and thus not aligned with the New Text tradition sponsored by Emperor An, enhanced the emperor's Confucian credentials when he presented his groundbreaking dictionary to the court, the Shuowen Jiezi.[297]

Financial troubles only worsened in Emperor Shun's reign, as many public works projects were handled at the local level without the central government's assistance.[298] Yet his court still managed to supervise the major efforts of disaster relief, aided in part by a new invention in 132 of a seismometer by the court astronomer Zhang Heng (78–139) who used a complex system of a vibration-sensitive swinging pendulum, mechanical gears, and falling metal balls to determine the direction of earthquakes hundreds of kilometers (miles) away.[299][300][301] Shun's greatest patronage of scholarship was repairing the now dilapidated Imperial University in 131, which still operated as a pathway for young gentrymen to enter civil service.[302] At the beginning of his reign officials protested the fact that the eunuch Sun Cheng and his associates were made marquises and further protest in 135 when the eunuchs were allowed to have adopted sons inherit their fiefs, yet the larger concern was over the rising power of the Liang faction.[298][303]

To abate the unseemly image of one child emperor after another being placed on the throne, Liang Ji chose the popular approach of granting general amnesties, awarding people with noble ranks, reducing the severity of penalties (the bastinado was no longer used), allowing exiled families to return home, and allowing convicts to settle on new land in the frontier.[304] Under his stewardship, the Imperial University was given a formal examination system whereby candidates would take exams on different classics over a period of years in order to gain entrance into public office.[305] Despite attempts at positive reform, Liang Ji was widely accused of corruption and greed.[306] Yet when Emperor Huan overthrew Liang by using eunuch allies, students of the Imperial University took to streets in the thousands chanting the names of the eunuchs they opposed; Valerie Hansen asserts this is one of the earliest student protests in history.[307]

During Liang's regency, Emperor Huan began advocating and reviving imperial patronage of Huang-Lao Daoism, which also became popular among contemporary rebel groups.[306] After Liang Ji was overthrown, Emperor Huan distanced himself more and more from the Confucian establishment and instead sought legitimacy through his patronage of Huang-Lao Daoism, which was incidentally not favored by the next Han emperors.[308] As the economy worsened, Emperor Huan busied himself with the construction of new hunting parks, imperial gardens, and palace buildings, especially the expansion of his harem housing thousands of concubines (Crespigny writes perhaps even more than Faisal of Saudi Arabia).[309] The scholarly gentry class became alienated by Emperor Huan's corrupt government dominated by eunuchs and many refused nominations to serve in office (since current Confucian beliefs dictated that morality and personal relationships superseded public service).[308][310]

Foreign relations and war of middle Eastern Han

At the beginning of Empress Dowager Deng's regency over An, the Protector General of the Western Regions Ren Shang (d. 118) was besieged at Kashgar; although he was able to break the siege, he was recalled and replaced before the Empress Dowager began to withdraw forces from the troubled Western Regions in the summer of 107.[311] The Qiang peoples, who had been settled by the government in various parts of Han's frontiers since the reign of Emperor Jing (but mostly concentrated in Qinghai and Tibet),[312] resented their forced conscription as soldiers for Han in this region, and began a devastating revolt in the northwestern province of Liang that would last until 118 and cut off Han's access to Central Asia.[313] The problem was exacerbated in 109 by a combined Southern Xiongnu, Xianbei, and Wuhuan rebellion in the northeast.[313] The total monetary cost for putting down the Qiang rebellion in Liang was 24,000,000 cash, while the people of four entire commanderies within Liang province were resettled elsewhere in China after 110 CE.[313][314] Following Ban Yong's reopening of relations with the states of the Western Regions in 123,[315] three of these Liang province commanderies were reestablished in 129, only to be withdrawn again a decade later.[316] Even after Liang province was settled again, there was another massive rebellion there in 184, only this time the rebels were Han Chinese, Qiang, Xiongnu, and Yuezhi.[317] However, from this point even into the last decade of Han, the kingdoms of the Tarim Basin were still sending tribute and hostages to the Han court, while the agricultural garrison at Hami was not gradually abandoned until after 153 CE.[318]

Of perhaps greater consequence for the Han Dynasty and future dynasties was the ascendance of the Xianbei people, who filled the vacuum of power on the vast northern steppe after the Northern Xiongnu were defeated by Han and fled to the Ili River valley (in modern Kazakhstan) in 91 CE.[319] The Xianbei quickly occupied the deserted territories and incorporated some 100,000 remnant Xiongnu families into their new federation, which by the mid 2nd century CE stretched from the western borders of the Buyeo Kingdom in Manchuria, to the Dingling in southern Siberia, and all the way west to the Ili River valley of the Wusun people.[320] Although they raided Han in 110 CE to force a negotiation of better trade agreements, the later leader Tanshihuai 檀石槐 (d. 180 CE) refused kingly titles and tributary arrangements offered by Emperor Huan and defeated Chinese armies under Emperor Ling.[321] When Tanshihuai died in 180, the Xianbei Federation largely fell apart, yet it grew powerful once more during the 3rd century.[322]