Mercury (planet)

Template:Planet Infobox/Mercury Mercury is the closest planet to the Sun, and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System. Mercury ranges from −0.4 to 5.5 in apparent magnitude, and its greatest angular separation from the Sun (greatest elongation) is only 28.3°, meaning it is only seen in twilight. The planet remains comparatively little-known: the only spacecraft to approach Mercury was Mariner 10 from 1974 to 1975, which mapped only 40–45% of the planet's surface.

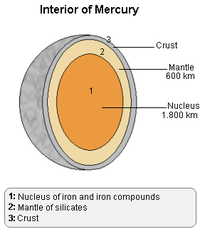

Physically, Mercury is similar in appearance to the Moon as it is heavily cratered. It has no natural satellites and no atmosphere. The planet has a large iron core which generates a magnetic field about 1% as strong as that of the Earth. Surface temperatures on Mercury range from about 90-700 K, with the subsolar point being the hottest and the bottoms of craters near the poles being the coldest.

The Romans named the planet after the fleet-footed messenger god Mercury, probably for its fast apparent motion in the twilight sky. The astronomical symbol for Mercury (Unicode: ☿) is a stylized version of the god's head and winged hat atop his caduceus. Before the 5th century BC, Greek astronomers believed the planet to be two separate objects. The Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese cultures refer to the planet as the water star, 水星, based on the Five Elements.

Historical understanding

Mercury has been known since at least the time of the Sumerians (3rd millennium BC), who called it Ubu-idim-gud-ud. The earliest recorded detailed observations were made by the Babylonians, who called it gu-ad or gu-utu. It was given two names by the ancient Greeks: Apollo when visible in the morning sky and Hermes when visible in the evening. However, Greek astronomers came to understand that the two names referred to the same body, with Pythagoras's being the first to propose the idea. Heraclitus even believed that Mercury and Venus orbited the Sun, not the Earth.

In 1631, Pierre Gassendi, who viewed the transit of Mercury predicted by Johannes Kepler, became the first person to observe the transit of a planet across the Sun. In 1639, Giovanni Zupi used a telescope to discover that the planet had orbital phases similar to Venus and the Moon. The observation demonstrated conclusively that Mercury orbited around the Sun.

Physical characteristics

Temperature and sunlight

The mean surface temperature of Mercury is 452 K, but it ranges from 90–700 K; by comparison, the temperature on Earth varies by only about 150 K. The sunlight on Mercury's surface is 6.5 times as intense as it is on Earth, with the solar constant having a value of 9.13 kW/m².

Surface features

During and shortly following the formation of Mercury, it was heavily bombarded by comets and asteroids for a period of about 800 million years. During this period of intense crater formation, the surface received impacts over its entire surface, facilitated by the lack of any atmosphere to slow impactors down. During this time, the planet was volcanically active; basins such as the Caloris Basin were filled by magma from within the planet, which produced smooth plains similar to the maria found on the Moon.

Apart from craters with diameters in the range of hundreds of meters to hundreds of kilometers, there are others of gigantic proportions such as Caloris, the largest structure on the surface of Mercury with a diameter of 1,300 km. The impact was so powerful that it caused lava eruptions from the crust of the planet and left a concentric ring over 2 km tall surrounding the impact crater. The consequences of Caloris are also impressive; it is widely accepted as the cause for the fractures and leaks on the opposite side of the planet.

The plains of Mercury have two distinct ages: the younger plains are less heavily cratered and probably formed when lava flows buried earlier terrain. One unusual feature of the planet's surface is the numerous compression folds which criss-cross the plains. It is thought that as the planet's interior cooled it contracted, and its surface began to deform. The folds can be seen on top of other features, such as craters and smoother plains, indicating that they are more recent. Mercury's surface is also flexed by significant tidal bulges raised by the Sun. The Sun's tides on Mercury are about 17% stronger than the Moon's on Earth.[1]

Mercury's terrain features are officially given the following designations:

- Craters (see List of craters on Mercury)

- Albedo features — areas of markedly different reflectivity

- Dorsa — ridges (see List of ridges on Mercury)

- Montes — mountains (see List of mountains on Mercury)

- Planitiae — plains (see List of plains on Mercury)

- Rupes — scarps (see List of scarps on Mercury)

- Valles — valleys (see List of valleys on Mercury)

Interior composition

Mercury has a relatively large iron core (even when compared to Earth). Mercury's composition is approximately 70% metallic and 30% silicate. The average density is 5430 kg/m³, which is slightly less than Earth's density. Despite having so much iron, the reason Mercury has a lower density than Earth is that the latter's mass is about 20 times greater, resulting in a more highly compressed interior with a high density. The iron core fills 42% of the planet's volume (Earth's core only fills 17%).

Surrounding the core is a 600 km mantle. It is thought that early in Mercury's history, a giant impact with a body several hundred kilometres across stripped the planet of much of its original mantle material, resulting in the relatively thin mantle compared to the sizable core.[2]

Rotation

It was formerly thought that Mercury was tidally locked with the Sun, rotating once for each orbit and keeping the same face directed towards the Sun at all times, in the same way that the same side of the Moon always faces the Earth. However, radar observations in 1965 proved that the planet has a 3:2 spin-orbit resonance, rotating three times for every two revolutions around the Sun; the eccentricity of Mercury's orbit makes this resonance stable. The original reason astronomers thought it was tidally locked was because whenever Mercury was best placed for observation, it was always at the same point in its 3:2 resonance, hence showing the same face. This would be also the case if it was totally locked. Due to Mercury's 3:2 spin-orbit resonance, a solar day (the length between two meridian transits of the Sun) lasts about 176 Earth days. A sidereal day (the period of rotation) lasts about 58.7 Earth days

At certain points on Mercury's surface, an observer would be able to see the Sun rise about halfway, then reverse and set before rising again, all within the same Mercurian day. This is because approximately four days prior to perihelion, Mercury's orbital velocity exactly equals its rotational velocity so that the Sun's apparent motion ceases; at perihelion, Mercury's orbital velocity then exceeds the rotational velocity. Thus, the Sun appears to be retrograde. Four days after perihelion, the Sun's normal apparent motion resumes.

Mercury's axial tilt is only 0.01 degrees. This is over 300 times smaller than that of Jupiter, which is the second smallest axial tilt of all planets at 3.1 degrees. This means an observer at Mercury's equator never sees the sun more than 1/100 of one degree north or south of the zenith.

Orbit

The orbit of Mercury has a high eccentricity, with the planet's distance from the Sun ranging from 46 million to 70 million kilometres. Among the major planets, only Pluto has a more eccentric orbit. However, because of the smallness of Mercury's orbit, all of the planets except the Earth and Venus have a larger spread between perihelion and aphelion (Mars' is 42.6 Gm to Mercury's 23.8 Gm, for example). There are even several outer planet satellites that beat Mercury's spread: Saturn's S/2004 S 18 (with 30.8 Gm) and Neptune's Psamathe and S/2002 N 4 (42.0 and 47.9 Gm, respectively).

When it was discovered, the slow precession of Mercury's orbit around the Sun could not be completely explained by Newtonian mechanics, and for many years it was hypothesized that another planet might exist in an orbit even closer to the Sun to account for this perturbation (other explanations considered included a slight oblateness of the Sun). The hypothetical planet was even named Vulcan. However, in the early 20th century, Albert Einstein's General Theory of Relativity provided a full explanation for the observed precession. Mercury's precession showed the effects of mass dilation, providing a crucial observational confirmation of Einstein's predictions. This was a very slight effect: the Mercurian relativistic perihelion advance excess is a mere 43 arcseconds per century. The effect is even smaller for the remaining planets, being 8.6 arcseconds per century for Venus, 3.8 for the Earth, and 1.3 for Mars.

Research indicates that the eccentricity of Mercury's orbit varies chaotically from 0 (circular) to a very high 0.47 over millions of years. This is thought to explain Mercury's 3:2 spin-orbit resonance (rather than the more usual 1:1), since this state is more likely to arise during a period of high eccentricity.[3]

Magnetosphere

Despite its slow rotation, Mercury has a relatively strong magnetosphere, with 1% of the magnetic field strength generated by Earth. It is possible that this magnetic field is generated in a manner similar to Earth's, by a dynamo of circulating liquid core material. However, scientists are unsure whether Mercury's core could still be liquid,[4] although it could perhaps be kept liquid by tidal effects during periods of high orbital eccentricity. It is also possible that Mercury's magnetic field is a remnant of an earlier dynamo effect that has now ceased, with the magnetic field becoming "frozen" in solidified magnetic materials.

Iron content

Mercury has a higher iron content than any other object in the solar system. Several theories have been proposed to explain Mercury's high metallicity. One theory is that Mercury originally had a metal-silicate ratio similar to common chondrite meteors and a mass approximately 2.25 times its current mass, but that early in the solar system's history Mercury was struck by a planetesimal of approximately 1/6 that mass. The impact would have stripped away much of the original crust and mantle, leaving the core behind. A similar theory has been proposed to explain the formation of Earth's Moon (see giant impact theory).

Alternatively, Mercury may have formed from the solar nebula before the Sun's energy output had stabilized. The planet would initially have had twice its present mass. But as the protosun contracted, temperatures near Mercury could have been between 2500–3500 K; and possibly even as high as 10000 K. Much of Mercury's surface rock would have vaporized at such temperatures, forming an atmosphere of "rock vapor" which would have been carried away by the solar wind.

A third theory suggests that the solar nebula caused drag on the particles from which Mercury was accreting, which meant that lighter particles were lost from the accreting material. Each of these theories predicts a different surface composition. Hence, one of the aims of the MESSENGER mission to the planet is to take observations that will allow the theories to be tested.[5] Tentative suggestions have been made that Mercury may be a Chthonian planet.

Observing Mercury

Observation of Mercury is complicated by its proximity to the Sun, as it is lost in the Sun's glare for much of the time. At most other times, Mercury can be observed for only a brief period during either morning or evening twilight.

Mercury exhibits moon-like phases as seen from Earth, being "new" at inferior conjunction and "full" at superior conjunction. The planet is rendered invisible on both of these occasions by virtue of its rising and setting in concert with the Sun in each case. The half-moon phase occurs at greatest elongation, when Mercury rises earliest before the Sun when at greatest elongation west, and setting latest after the Sun when at greatest elongation east (its separation from the Sun ranging from 18.5° if it is at perihelion at the time of the greatest elongation to 28.3° if it is at aphelion).

Mercury is brightest as seen from Earth when it is at a "gibbous" phase, between half-full and full. Mercury's smaller orbit means it is not much farther away, and the fuller phase more than outweighs its greater distance from Earth.

Mercury attains inferior conjunction every 116 days on average, but this interval can range from 111 days to 121 days due to the planet's eccentric orbit. Its period of retrograde motion as seen from Earth can vary from 8 to 15 days on either side of inferior conjunction. This large range also arises from the planet's high degree of orbital eccentricity.

Mercury is more often easily visible from Earth's Southern Hemisphere than from its Northern Hemisphere; this is due to the fact that its maximum possible elongations west of the Sun always occur when it is early autumn in the Southern Hemisphere, while its maximum possible eastern elongations happen when the Southern Hemisphere is having its late winter season. In both of these cases, the angle Mercury strikes with the ecliptic is maximized, allowing it to rise several hours before the Sun in the former instance and not set until several hours after sundown in the latter in countries located at South Temperate Zone latitudes, such as Argentina and New Zealand. By contrast, at northern temperate latitudes Mercury is never above the horizon of a more-or-less fully dark night sky. Mercury can, like several other planets and the brightest stars, be seen during a total solar eclipse.

The only observed instance of an occultation of Mercury by Venus was by John Bevis at the Royal Greenwich Observatory on May 28, 1737.

| Greatest Eastern Elongation | Stationary, retrograde | Inferior conjunction | Stationary, prograde | Greatest Western Elongation | Superior conjunction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 July 2005 - 26.2° | 22 July 2005 | 5 August 2005 | 15 August 2005 | 23 August 2005 - 18.4° | 18 September 2005 |

| 3 November 2005 - 23.5° | 14 November 2005 | 24 November 2005 | 4 December 2005 | 12 December 2005 - 21.1° | 26 January 2006 |

| 24 February 2006 - 18.1° | 2 March 2006 | 12 March 2006 | 24 March 2006 | 8 April 2006 - 27.8° | 18 May 2006 |

| 20 June 2006 - 24.9° | 4 July 2006 | 18 July 2006 | 28 July 2006 | 7 August 2006 - 19.2° | 18 May 2006 |

| 17 October 2006 - 24.8° | 28 October 2006 | 11 November 2006 | 17 November 2006 | 25 November 2006 - 19.9° | 7 January 2007 |

| 7 February 2007 - 18.2° | 13 February 2007 | 23 February 2007 | 7 March 2007 | 22 March 2007 - 27.7° | 3 May 2007 |

| 2 June 2007 - 23.4° | 15 June 2007 | 28 June 2007 | 10 July 2007 | 20 July 2007 - 20.3° | 15 August 2007 |

| 29 September 2007 - 26° | 12 October 2007 | 23 October 2007 | 1 November 2007 | 8 November 2007 - 19° | 17 December 2007 |

| 22 January 2008 - 18.6° | 28 January 2008 | 6 February 2008 | 18 February 2008 | 3 March 2008 - 27.1° | 16 April 2008 |

| 14 May 2008 - 21.8° | 26 May 2008 | 7 June 2008 | 19 June 2008 | 1 July 2008 - 21.8° | 29 July 2008 |

| 11 September 2008 - 26.9° | 24 September 2008 | 6 October 2008 | 15 October 2008 | 22 October 2008 - 18.3° | 25 November 2008 |

| 4 January 2009 - 19.3° | 11 January 2009 | 20 January 2009 | 1 February 2009 | 13 February 2009 - 26.1° | 31 March 2009 |

| 26 April 2009 - 20.4° | 7 May 2009 | 18 May 2009 | 30 May 2009 | 13 June 2009 - 23.5° | 14 July 2009 |

| 24 August 2009 - 27.4° | 6 September 2009 | 20 September 2009 | 28 September 2009 | 6 October 2009 - 17.9° | 5 November 2009 |

| 18 December 2009 - 20.3° | 26 December 2009 | 4 January 2010 | 15 January 2010 | 27 January 2010 - 24.8° | 14 March 2010 |

| 8 April 2010 - 19.3° | 18 April 2010 | 28 April 2010 | 11 May 2010 | 26 May 2010 - 25.1° | 28 June 2010 |

| 7 August 2010 27.2° | 20 August 2010 | 3 September 2010 | 12 September 2010 | 19 September 2010 - 18.2° | 17 October 2010 |

| 1 December 2010 - 21.2° | 10 December 2010 | 20 December 2010 | 30 December 2010 | 9 January 2011 - 23.3° | 25 February 2011 |

| 23 March 2011 - 18.6° | 30 March 2011 | 9 April 2011 | 22 April 2011 | 7 May 2011 - 26.6° | 12 June 2011 |

| 20 July 2011 - 26.8° | 2 August 2011 | 17 August 2011 | 26 August 2011 | 3 September 2011 - 18.1° | 28 September 2011 |

| 14 November 2011 - 22.7° | 24 November 2011 | 4 December 2011 | 14 December 2011 | 23 December 2011 - 21.8° | 7 February 2012 |

| 5 March 2012 - 18.2° | 11 March 2012 | 21 March 2012 | 3 April 2012 | 18 April 2012 - 27.5° | 27 May 2012 |

| 1 July 2012 - 25.7° | 14 July 2012 | 28 July 2012 | 7 August 2012 | 16 August 2012 - 18.7° | 10 September 2012 |

| 26 October 2012 - 24.1° | 7 November 2012 | 17 November 2012 | 26 November 2012 | 4 December 2012 - 20.6° | 18 January 2013 |

| 16 February 2013 - 18.1° | 22 February 2013 | 4 March 2013 | 16 March 2013 | 31 March 2013 - 27.8° | 11 May 2013 |

| 12 June 2013 - 24.3° | 25 June 2013 | 9 July 2013 | 20 July 2013 | 30 July 2013 - 19.6° | 24 August 2013 |

| 9 October 2013 - 25.3° | 21 October 2013 | 1 November 2013 | 10 November 2013 | 18 November 2013 - 19.5° | 29 December 2013 |

| 31 January 2014 - 18.4° | 6 February 2014 | 15 February 2014 | 27 February 2014 | 14 March 2014 - 27.6° | 26 April 2014 |

| 25 May 2014 - 22.7° | 7 June 2014 | 19 June 2014 | 1 July 2014 | 12 July 2014 - 20.9° | 8 August 2014 |

| 21 September 2014 - 26.4° | 4 October 2014 | 16 October 2014 | 25 October 2014 | 1 November 2014 - 18.7° | 8 December 2014 |

| 14 January 2015 - 18.9° | 21 January 2015 | 30 January 2015 | 11 February 2015 | 24 February 2015 - 26.8° | 10 April 2015 |

| 7 May 2015 - 21.2° | 19 May 2015 | 30 May 2015 | 11 June 2015 | 24 June 2015 - 22.5° | 23 July 2015 |

| 4 September 2015 - 27.1° | 17 September 2015 | 30 September 2015 | 8 October 2015 | 16 October 2015 - 18.1° | 17 November 2015 |

| 29 December 2015 - 19.7° | 5 January 2016 | 14 January 2016 | 25 January 2016 | 7 February 2016 - 25.6° | 23 March 2016 |

| 18 April 2016 - 19.9° | 29 April 2016 | 9 May 2016 | 21 May 2016 | 5 June 2016 - 24.2° | 7 July 2016 |

| 16 August 2016 - 27.4° | 30 August 2016 | 12 September 2016 | 21 September 2016 | 28 September 2016 - 17.9° | 27 October 2016 |

| 11 December 2016 - 20.8° | 19 December 2016 | 28 December 2016 | 8 January 2017 | 19 January 2017 - 24.1° | 7 March 2017 |

| 1 April 2017 - 19° | 10 April 2017 | 20 April 2017 | 2 May 2017 | 17 May 2017 - 25.8° | 21 June 2017 |

| 30 July 2017 - 27.2° | 12 August 2017 | 26 August 2017 | 4 September 2017 | 12 September 2017 - 17.9° | 8 October 2017 |

| 24 November 2017 - 22° | 3 December 2017 | 13 December 2017 | 23 December 2017 | 1 January 2018 - 22.7° | 17 February 2018 |

| 15 March 2018 - 18.4° | 22 March 2018 | 1 April 2018 | 14 April 2018 | 29 April 2018 - 27° | 6 June 2018 |

| 12 July 2018 - 26.4° | 25 July 2018 | 9 August 2018 | 18 August 2018 | 26 August 2018 - 18.3° | 21 September 2018 |

| 6 November 2018 - 23.3° | 17 November 2018 | 27 November 2018 | 6 December 2018 | 15 December 2018 - 21.3° | 30 January 2019 |

| 27 February 2019 - 18.1° | 5 March 2019 | 15 March 2019 | 27 March 2019 | 11 April 2019 - 27.7° | 21 May 2019 |

| 23 June 2019 - 25.1° | 7 July 2019 | 21. July 2019 | 31 July 2019 | 9 August 2019 - 19.1° | 4 September 2019 |

| 20 October 2019 - 24.6° | 31 October 2019 | 11 November 2019 | 20 November 2019 | 28 November 2019 - 20.1° | 10 January 2020 |

| 10 February 2020 - 18.2° | 16 February 2020 | 26 February 2020 | 9 March 2020 | 24 March 2020 - 27.8° | 4 May 2020 |

| 4 June 2020 - 23.6° | 17 June 2020 | 1 July 2020 | 12 July 2020 | 22 July 2020 - 20.1° | 17 August 2020 |

| 1 October 2020 - 25.8° | 14 October 2020 | 25 October 2020 | 3 November 2020 | 10 November 2020 - 19.1° | 20 December 2020 |

Exploration

Reaching Mercury from Earth poses significant technical challenges since the planet orbits three times closer to the Sun than the Earth. A Mercury-bound spacecraft launched from Earth must travel over 91 million kilometers into the Sun's gravitational potential well. From a stationary start, a spacecraft would require no delta-v or energy to fall towards the Sun. However, starting from the Earth with an orbital speed of 30 km/s, the spacecraft's significant angular momentum resists sunward motion. Hence, the spacecraft must change its velocity considerably to enter into a Hohmann transfer orbit that passes near Mercury.

In addition, the potential energy liberated by moving down the Sun's potential well becomes kinetic energy. This increases the velocity of the spacecraft. Without correcting for this, the spacecraft would be moving too quickly by the time it reached the vicinity of Mercury to land safely or enter a stable orbit. The approaching spacecraft cannot use aerobraking to help enter orbit around Mercury and must rely on rocket boosters, since the planet has no atmosphere. Hence, a trip to Mercury requires even more rocket fuel than that required to escape the solar system completely. As a result of these problems, there have not been many missions to Mercury as of 2005.

NASA

The only spacecraft to approach Mercury was NASA's Mariner 10 (1974-1975). The spacecraft used the gravity of Venus to adjust its orbital velocity so that it could approach Mercury. Mariner 10 provided the first close-up images of Mercury's surface. The spacecraft made three close approaches to Mercury, the closest of which took it to within 327 km of the surface. Unfortunately, the same face of the planet was lit at each close approach, resulting in less than 45% of the planet's surface's being mapped. Mariner 10 also found the first evidence for Mercury's magnetic field and measured temperatures across its surface.[6]

A second NASA mission to Mercury, named MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging), was launched on August 3, 2004, from the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station aboard a Boeing Delta 2 rocket. The MESSENGER spacecraft will make three flybys of Mercury in 2008 and 2009 before entering a year-long orbit of the planet in March 2011. It will explore the planet's atmosphere, composition, and structure.

Japan and the ESA

Japan is planning a joint mission with the European Space Agency called BepiColombo, which will orbit Mercury with two probes: one to map the planet and the other to study its magnetosphere. An original plan to include a lander has been shelved. Russian Soyuz rockets will launch the probes starting in 2011-2012. The probes will reach Mercury about four years later, orbiting and charting its surface and magnetosphere for a year.

See also

Notes

- ^ Van Hoolst, T., Jacobs, C. (2003), Mercury's tides and interior structure, Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 108, p. 7.

- ^ Benz, W., Slattery, W. L., Cameron, A. G. W. (1988), Collisional stripping of Mercury's mantle, Icarus, v. 74, p. 516-528.

- ^ Correia, A. C. M., Laskar, J. (2004), Mercury's capture into the 3/2 spin-orbit resonance as a result of its chaotic dynamics, Nature, v. 429, p. 848-850.

- ^ Spohn, T., Breuer, D. (2005), Core Composition and the Magnetic Field of Mercury, American Geophysical Union, Spring Meeting 2005

- ^ Mercury: The Key to Terrestrial Planet Evolution (2005). JHU/APL - Messenger.

- ^ Mariner 10 (October 20, 2005). NSSDC Master Catalog Display: Spacecraft.

References

- Shchuko, O. B. (2004). Mercury: can any ice exist at subpolar regions?, Advances in Space Research, v. 33, p. 2156-2160

- Comins, Neil F. (2001). Discovering the Essential Universe.

- Zuber, Maria T. (2004). Mercury. World Book Online Reference Center. World Book, Inc. Accessed at nasa.gov.

External links

- Atlas of Mercury - NASA

- NASA's Mercury fact sheet

- 'BepiColombo', ESA's Mercury Mission

- 'Messenger', NASA's Mercury Mission

- SolarViews.com - Mercury

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA