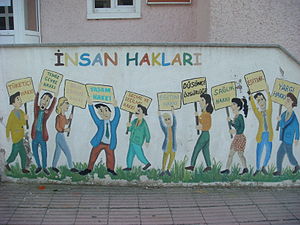

Human rights in Turkey

|

|---|

|

|

Human rights in Turkey are protected by a variety of international law treaties, which takes precedence over domestic legislation, according to the 1982 Constitution.

The issue of human rights is of high importance for the negotiations with the European Union (EU). A large part of the legislation criticized by human rights organizations are included in the 1982 Constitution or other laws passed following the 1980 military coup. On re-election in July 2007, the AKP (religious conservative) government pledged to rewrite the 1982 constitution, but after months of discussion it has failed to make public a draft constitution,[1] due to severe opposition[2] stemming from the belief that it may contain hidden clauses aimed towards eroding the foundations of the Republic.

Acute human rights issues include in particular the Kurdish matter, as the state of emergency declared between 1987 and 2002 in the Southeastern Anatolia Region due to the conflict with the PKK, a militant secessionist Kurdish group, has caused numerous human rights violations over the years. Censorship and military intervention in politics are also common human rights issues.

International and domestic legislation

The Republic of Turkey has entered into various human rights commitments—beginning with those of the Turkish Constitution, Part Two of which guarantees "fundamental rights and freedoms" such as the right to life, security of person, and right to property. In addition, Turkey has signed treaties including:

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1949).[3]

- The European Convention on Human Rights (1954),[4] which places Turkey under the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). In 1987, Turkey accepted the right to apply individually to the ECHR, a measure which became effective in 1990.[5]

Furthermore, as a country currently in accession negotiations with the European Union, Turkey is obliged to ensure consistency of its laws with the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

Constitutional reforms were thus enacted in June 2004, transforming for instance State Security Courts into Heavy Penal Courts.

Common violations

According to Human Rights Watch (2002), Turkish Human Rights Association has calculated that Turkish law and regulations contain more than 300 provisions constraining freedom of expression, religion, and association.[7] Many of the repressive provisions found in the Press Law, the Political Parties Law, the Trade Union Law, the Law on Associations, and other legislation were imposed by the military junta after its coup in 1980.[7]

Turkey's mixed human rights record has been highly politicized in the debate surrounding the country's probable ascendance to membership in the European Union. Beginning with the foundation of a secular republic in 1923, and continuing with founding membership in the United Nations and participation in the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, Turkey made significant commitments to the advancement of human rights. However, its authoritarian tradition, periods of military rule, increasing social inequality, and economic crises have led to policies that undermine human rights. While legislative reforms and civil social activism since the 1980s have contributed greatly to the advancement of human rights, recent progress is threatened by the rise of nationalism, persistent gender inequality, and economic hardship.

In Human Rights in Turkey, twenty-one Turkish and international scholars from various disciplines examine human rights policies and conditions since the 1920s, at the intersection of domestic and international politics, as they relate to all spheres of life in Turkey. A wide range of rights, such as freedom of the press and religion, minority, women's, and workers' rights, and the right to education, are examined in the context of the history and current conditions of the Republic of Turkey.

In light of the events of September 11, 2001, and subsequent developments in the Middle East, recent proposals about modeling other Muslim countries after Turkey add urgency to an in-depth study of Turkish politics and the causal links with human rights. The scholarship presented in Human Rights in Turkey holds significant implications for the study of human rights in the Middle East and around the globe.

Zehra F. Kabasakal Arat is Juanita and Joseph Leff Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Women's Studies at Purchase College of the State University of New York.

- Various restrictions on freedom of speech (e.g., Article 301 of the Turkish Constitution prohibits "denigrating Turkishness") and assembly, as well as arbitrary electoral and parliamentary barriers.

- Many secularists accuse the moderate religious party AKP of advocating an Islamic government, a charge which the AKP denies. Meanwhile, many observant Muslims complain that their religious freedom (e.g., to dress religiously), has been unfairly restricted by secularists. Controversies over the AKP resulted in an indictment before the Supreme Court of Appeals. The court judged on July 30, 2008 that the party was the focus of actions that were anti-secular and halved its funding from the Central Bank as a penalty, refusing however to disband it.[8] Calls have been made by various parties, including the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), to reform the Political Parties Law and restrict political parties closure.[9]

- Ethnic and religious minorities (such as the Kurds and Alevi, respectively) complain of violations of religious, cultural, and political rights arising from a widespread insistence that Turkey is a cultural as well as political unity. 33 Alevis were killed during the 1993 Sivas massacres. The responsibles were afterwards given life sentences. The issue of the Armenian genocide controversy, left over from the Ottoman era, complicates Turkey's external relations but also impacts the freedom-of-speech issue.

- Various violations of women's rights (such as virginity tests for women entering university[10]) have been phased out, but others remain.[11] Often the situation "on the ground" (particularly in rural areas) does not reflect that which is prescribed by law.

- By some accounts, Turkey has the second largest population of internally displaced persons in the world, whose plight has attracted international concern.[12]

Political party bans, freedom of association

New York) - The killing of Ebru Soykan, a prominent transgender human rights activist, on March 10, 2009, shows a continuing climate of violence based on gender identity that authorities should urgently take steps to combat, Human Rights Watch said today. News reports and members of a Turkish human rights group said that an assailant stabbed and killed Ebru, 28, in her home in the center of Istanbul.

Members of Lambda Istanbul, which works for the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and transsexual (LGBTT) people, told Human Rights Watch that in the last month Ebru had asked the Prosecutor's Office for protection from the man who had beaten her on several occasions and threatened to kill her. Lambda Istanbul was told that a few weeks ago police detained the man but released him two hours later. The same man is under police custody as the murder suspect.

The Kurdish Democratic Society Party (to which Leyla Zana is a member) is also the focus of a closure case,[1] due to be soon examined, on charges of separatism. As with the AKP, the evidence in the indictment against the Democratic Society Party consists predominantly of nonviolent speeches and statements by party officials and deputies.[1]

Extrajudicial killings

Elements of the Turkish military police have been discovered murdering civilian noncombatants as recently as 2005 (when three perpetrators were caught with a list of names of intended victims, all Kurds). The resulting investigation was stymied by the refusal of the military to cooperate.[13] (See also List of assassinated people from Turkey.)

Investigations concerning the November 2005 Şemdinli bombing trial have been blocked by the military [14]. All the Van judges and prosecutors associated with the Şemdinli bookshop bombing case were transferred to other cities following a June 2007 decree.[14]

Violence against journalists and intellectuals

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

Although not officially censored, many journalists and intellectuals have been victims, over the years, of violent attacks, including assassinations.

Abdi İpekçi, editor of the left-wing newspaper Milliyet was assassinated in 1979 by Mehmet Ali Ağca, a member of the Grey Wolves ultra-nationalist organization who later attempted to kill the Pope.

Muammer Aksoy, a Kemalist professor of law, was assassinated in 1990 by Islamists. The same year, left-wing activist, and feminist politician Bahriye Üçok was also assassinated by Islamists. Left-wing intellectual Aziz Nesin, who had attempted to publish in Turkey Salman Rushdie's Satanic Verses, was targeted along with Alevis, including Hasret Gültekin, a famous Kurdish bağlama saz player, in Sivas in July 1993. An arson led by Sunni extremists led to 36 deaths, although Aziz Nesin managed to survive.

Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink was convicted under Article 301 and given a suspended six month sentence, shortly before being assassinated on January 19, 2007 by an ultra-nationalist student, Ogün Samast. Ultranationalist lawyer Kemal Kerinçsiz, who filed numerous suits against writers on charges of breaching Article 301, has been detained in 2008 in the frame of investigations concerning the terrorist Ergenekon network.[15] Ergenekon has been suspected by police investigators to be behind Hrant Dink's assassination.[16]

Individual rights

Capital punishment

There have been no capital punishment in Turkey since 1984, and the practice was formally abolished for offences during peacetime in 2002, and for offences during wartime in 2004.[17]

Gender equality

In the 1930s, Turkey became one of the first countries in the world to give full political rights to women, including the right to elect (in 1930) and to be elected (in 1934), to every political office.

Article 10 of the Turkish Constitution bans any discrimination, state or private, on the grounds of sex. Turkey was one of the first countries to elect a female prime minister, Tansu Çiller in 1995. It is also the first country which had a woman as the President of its Constitutional Court, Tülay Tuğcu. In addition, Turkish Council of State, the court of last resort for administrative cases, also has a woman judge Sumru Çörtoğlu as its President.

Since 1985, Turkish women have the right to freely exercise abortions in the first 10 weeks of pregnancy and the right to contraceptive medicine paid for by the Social Security. This is in contrast with the policies of certain EU countries, such as Poland and Ireland, that ban abortion. Modifications to the Civil Code in 1926 gave the right to women to initiate and obtain a divorce; a right still not recognized in Malta,[18] an EU country.

Nevertheless, in Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia regions, older attitudes prevail among the local Kurdish, Turkish and Arab populations, where women still face domestic violence, forced marriages, and so-called honor killings.[19] To combat this, the government and various other foundations are engaged in education campaigns in Southeastern Anatolia to improve the rate of literacy and education levels of women.[20]

Recently, critics have pointed out that Turkey has become a major market for foreign women who are coaxed and forcibly brought to the country by international mafia to work as sex slaves, especially in big and touristic cities.[21][22][23]

A 2008 poll by the Women Entrepreneurs Association of Turkey showed that almost half of urban Turkish women believe economic independence for women is unnecessary reflecting, in the view of psychologist Leyla Navaro, a heritage of patriarchy.[24]

Freedom of expression and freedom of the press

Legislation

Article 26 of the Constitution guarantees freedom of expression. Articles 27 and 28 of the Constitution guarantee the "freedom of expression" and "unhindered dissemination of thought". Alinea 2 of Article 27 affirms that "the right to disseminate shall not be exercised for the purpose of changing the provisions of Articles 1, 2 and 3 of [the] Constitution", articles in question referring to the unitary, secular, democratic and republican nature of the state. A "mini-democracy package" was voted by Parliament in 2002.

There have been particular concerns over the restrictions on the publication and diffusion of material relating primarily to highly sensitive political subjects. According to the International PEN, roughly 60 writers, publishers and journalists [citation needed] have had charges brought against them under the 301st Article of the Turkish Penal Code that states: "A person who publicly insults Turkishness, the Republic or the Turkish Grand National Assembly, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term of six months to three years." It also states that "Expressions of thought intended to criticize shall not constitute a crime".

Trials

Even though certain high-profile cases (such as Orhan Pamuk or Elif Şafak, both about assertions related to the Armenian Genocide, an event that is disputed by Turkey) have ended in acquittals, the outcome of other cases are unclear. Reporters without Borders has raised concerns over the use of criminal defamation laws to punish those who criticise authorities.[25][26]

In 1999, Istanbul's mayor and current prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan was sentenced to 10 months' imprisonment under Article 312 for reading a few lines from a poem that had been authorized by the Ministry of Education for use in schools, and consequently had to resign.[7]

Minority languages

Since the liberalization of the audiovisual market in 1991, Turkey has developed an extremely vibrant and dynamic media. There are thousands of newspapers, TV channels and radio stations in the country, and they are guaranteed freedom in their editorial decisions by the constitution. The state-owned TRT has been broadcasting short programmes in a number of minority languages, including Bosnian and Kurdish, since 2003 — before which its use was prohibited (See below for Kurdish issues.)

The state broadcasts in Kurdish and Armenian, as well as Turkish.[27]

Freedom of religion

Although its population is overwhelmingly Muslim, Turkey is a secular country per Article 3 of its constitution, and thus has no official religion. Secularism in Turkey originates from Atatürk's 'Six Arrows' of Republicanism, Populism, Laïcité, Revolutionarism, Nationalism, and Statism.

Article 24 of the Turkish Constitution guarantees all residents of Turkey the right to adhere to any religion or philosophical belief, with some exceptions made for their expression in public spaces. The Constitutional Court has interpreted secularism in a way that doesn't allow for a person to wear religious symbols (e.g. a head scarf or a cross) in governmental and public institutions, and particularly while attending public schools and state universities. A recent ruling, enacted on June 5, 2008, stated that the parliament had violated the constitutional principle of secularism when it passed amendments (supported by the AKP and the MHP) to lift the headscarf ban on university campuses.[28]

Nevertheless, in its decision on November 10, 2005 in Leyla Şahin v. Turkey, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights ruled that such a ban was "legitimate" to prevent the influence of religion in state affairs.[29] Human Rights Watch, however, supports "lifting the current restrictions on headscarves in university on the grounds that the prohibition is an unwarranted infringement on the right to religious practice. Moreover, this restriction of dress, which only applies to women, is discriminatory and violates their right to education, freedom of thought, conscience, religion, and privacy." [28]

Conforming with the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court and the Council of State on secularism, faith-based schools are banned and all schools must follow a secular curriculum. Religious education may only be given by appointed teachers who have studied at Turkey's secular universities. In practice, only Sunni theology is taught.

There is a de facto domination of Sunni school of Islam within Turkish society, despite the protections offered by formal secularism. Sunni imams are nominated and paid by the state Directorate of Religious Affairs. The Alevis pray in cemevis, but the government funds only the building of mosques. Even though there have been attempts to expand state religious funding to Alevis, they are not considered a different Muslim school, but as part of the Sunni branch.

The situation of the non-Muslim minorities has also been open to criticism. The government doesn't nominate, nor pay for, any non-Muslim religious leaders. Turkey has been criticized by Greece, the European Union and several human rights NGOs for its refusal to recognize the Ecumenical title of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch in Istanbul and the closing of the Greek Orthodox theological school in Heybeliada (Halki), Istanbul in 1970s.

In 2009, the state's TV channel, TRT, announced its plan to air programs reflecting the interests of the Alevi minority.[27]

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Rights

Homosexual sexual relationships between consenting adults in private is not a crime in Turkey. The age of consent for both heterosexual and homosexual sex is eighteen. On the other hand, the criminal code has vaguely worded prohibitions on "public exhibitionism" and "offenses against public morality" that are sometimes used to discriminate against the LGBT community. As of 2009, Turkey neither has a law permitting homosexuals to get married, nor does it have a law against the discrimination of Turkey's LGBT community.

The major LGBT organizatios in Turkey are KAOS GL in Ankara, Lambda Istanbul in Istanbul Pink Life LGBT Association in Ankara, Rainbow Group in Antalya, Piramid LGBT Diyarbakir Initiative in Diyarbakir, Purple Hand LGBT Initiative in Eskisehir and Black Pink Triangle Izmir Association in Izmir.

Homosexuals have the right to exemption from military service, if they so request, only if their "condition" is verified by medical and psychological tests, which often involves presenting humiliating, belittling graphic proof of homosexuality, and anal examination.[30]

Disabled citizens

In recent years, the Turkish parliament has approved certain major laws to fight against and end discrimination against the disabled. However, this has not shown the desired effects on the ground because of a lack of economic resources and the absence of awareness programs.

In one particular case, an advocacy group for people with mental disabilities called Mental Disability Rights International criticized the treatment of the mentally ill in a report called "Behind Closed Doors: Human Rights Abuses in the Psychiatric Facilities, Orphanages and Rehabilitation Centers of Turkey".[31] As a result of this criticism, Turkey's largest psychiatric hospital, the Bakırköy state hospital in Istanbul, abolished the use of "unmodified" ECT procedures.[citation needed]

Conscientious objection

There is currently no provision for conscientious objection. Turkey and Azerbaijan are the only members of the Council of Europe that defend this view. In January 2006, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Turkey had violated Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights that prohibits degrading treatment in a case dealing with conscientious objection.[32] Another conscientious objector, Mehmet Tarhan, was sentenced to four years in prison by a military court in 2005 for refusing to do his military service, but he was later released in March 2006. However, he is still a convict and shall be arrested on sight. In a related case, journalist Perihan Mağden was tried and acquitted by a Turkish court for supporting Tarhan and advocating conscientious objection as a human right.

Ethnic rights

Turkish society contains elements from every ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire. Some Turks are descended from non-Turkic Ottoman ethnic groups who adopted a Turkish identity and some of them also see themselves as still belonging to one of those minority groups, often as a sub-group within the main Turkish society (for instance the Hamshenis in the North-East). Other important minority groups include the Kurds, Alevis (a distinct branch of Islam), Armenians, Chveneburi, Laz, Circassians, Azeris, Greeks, etc. (See Demographics of Turkey).

According to Article 66 of the Turkish Constitution, "everyone bound to the Turkish state through the bond of citizenship is a Turk". The Constitution affirms the principle of the indivisibility of the Turkish Nation and of constitutional citizenship that is not based on ethnicity. Consequently, the word "Turkish" legally refers to all citizens of Turkey, though individual interpretation can be more limited. According to the constitution, there are no minority rights since all citizens are equal before the law. Although the Treaty of Lausanne, before the proclamation of the Republic, guarantees some rights to non-Muslim minorities, in practise Turkey has recognised only Armenians, Greeks and Jews as minorities and excluded other non-Muslim groups, such as Assyrians and Yazidis, from the minority status and these rights.[33] Advocacy for protection of minorities' rights can lead to legal prosecutions as a number of provisions in Turkish law prohibits creation of minorities or alleging existence of minorites, such as Article 81 of the Law on Political Parties.

Until recent reforms, there were many legal restrictions on publishing in languages other than the only official one, Turkish, and publications in minority languages were not allowed. Since then, minorities have the right to publish and diffuse media, such as newspapers or audiovisual channels, in their own languages and operate private courses that teach any language spoken in Turkey. Turkish is still the only language that can be used in schools and universities as a first language. As concerns the Kurdish language, all such courses were closed down in 2004 by the owners. It must be noted, however, that those courses were shut down because of a grave lack of attendance and interest, and thus making the observers wonder the true extent of the demand for a separate Kurdish ethnic identity, rather than a Turkish one. Many buildings were rented for such courses by activists "in anticipation of a flood of students that never came." Kurdish language activists counter that the desire to learn Kurdish is there, but it must be taught in public schools.[13]

There have been certain calls by certain NGOs that Turkey should adopt the definitions of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. If Turkey were to become a signatory to this treaty, it would have to accept and subsidise the education of minorities in their own first languages, and that for at least all the period of mandatory education. However, it must be noted that, even France, a founding member of the European Union, has refused to apply this treaty within its territory following a ruling by its own Constitutional Court that has affirmed that doing so would be contrary to the principle of the indivisibility of the Republic and the nation affirmed in the First Article of the French Constitution. In addition to France, many other EU countries, namely Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland and Portugal have also refused to ratify this treaty. To this day only 21 member states of the Council of Europe out of 49 have proceeded with ratification.[34]

Kurdish people

Due to the large population of Turkish Kurds, successive governments have viewed the expression of a Kurdish identity as a potential threat to Turkish unity, a feeling that has been compounded since the armed rebellion initiated by the PKK in 1984. One of the main accusations of cultural assimilation comes from the state's historic suppression of the Kurdish language. Kurdish publications created throughout the 1960s and 1970's were shut down under various legal pretexts.[35] Following the military coup of 1980, the Kurdish language was officially prohibited from government institutions.[36] The Kurdish alphabet is not recognized.[36]

Since 2002, as part of its reforms aimed at European Union integration and under pressure to further the rights of Kurds, Turkey passed laws allowing Kurdish radio and television broadcasts as well the option of private Kurdish education. But this allowance came with many limitations, one of these limitations is quite interesting : It's forbidden to teach the language with these broadcasts. This is a very good example what kind of an approach they have for the language.[37]

In August 2009, Turkish government mentioned about restoring names of Kurdish villages (all Kurdish names had been changed with Turkish ones by the state), as well as considering allowing religious sermons to be made in Kurdish as part of reforms to answer the grievances of the ethnic minority and advance its EU candidacy. [38]

Workers' rights

The Constitution affirms the right of workers to form labor unions "without obtaining permission" and "to possess the right to become a member of a union and to freely withdraw from membership" (Article 51). Articles 53 and 54 affirm the right of workers to bargain collectively and to strike, respectively. However, rates of membership in labor unions are quite low, due to the fact that Turkish economy still experiences difficulties with corruption and massive numbers of workers not declared to the Social Security.

Turkey has had a standard state-run pensions system based on European models since the 1930s. Furthermore, since 1996, Turkey has a state-run unemployment insurance system, obligatory for all declared workers.

European Court of Human Rights judgments

| Number of decisions made by the ECHR.[5] | |

| Year | Decisions |

| 1995 | 3 |

| 1996 | 5 |

| 1997 | 8 |

| 1998 | 18 |

| 1999 | 19 |

| 2000 | 39 |

| 2001 | 218 |

| 2002 | 99 |

| 2003 | 123 |

| 2004 | 171 |

| 2005 | 290 |

| 2006 | 300 |

Nevertheless, Turkey's human rights record has long continued to attract scrutiny, both internally and externally. According to the Foreign Ministry, Turkey was sentenced to 33 million euros in 567 different cases between 1990—when Turkey effectively allowed individual applications to the European court of human rights (ECHR)—and 2006.[5] Most abuses were done in the South-East, in the frame of the conflict with the PKK.[5]

In 2007, there were 2830 applications lodged against the Republic of Turkey before the ECHR and consequently 331 judgments on the merits have been issued affirming 319 violations and 9 non-violations.[39] In 2008, Turkey ranked second after Russia in the list of countries with the largest number of human rights violation cases open at the European Court of Human Rights, with 9,000 cases pending as of August 2008.[5]

The ECHR has heard nine cases against Turkey concerning political party bans by the Constitutional Court of Turkey.[1] In all but one case (which concerned the Islamist Welfare Party), the European Court has ruled against the decision to ban, finding Turkey in violation of articles 10 and 11 of the European Convention (freedom of expression and freedom of association).[1] The ECHR's decision concerning the Welfare Party has been criticized for lack of consistency with its other decisions, in particular by Human Rights Watch.[1]

One ECHR judgment sentenced Turkey to a 103,000 euros fine for its decisions about the Yüksekova Gang (aka "the gang with uniforms"), related to the JİTEM clandestine gendarmerie intelligence unit. [5] The EHCR also sentenced in 2006 Turkey to a 28,500 euros fine for the JİTEM murder of 72-years-old Kurdish writer Musa Anter, in 1992 in Diyarbakir.[5] Other cases include the 2000 Akkoç v. Turkey judgment, concerning the assassination of a trade-unionist; or the Loizidou v. Turkey case in 1996, which set a precedent in the Cyprus dispute, as the ECHR ordered Turkey to give financial compensation to a person expelled from the Turkish-controlled side of Cyprus.

The ECHR also awarded in 2005 Kurdish deputy Leyla Zana 9000 € from the Turkish government, ruling Turkey had violated her rights of free expression. Zana, who had been recognized as prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International and had been awarded the Sakharov Prize by the European Parliament, had been jailed in 2004, allegedly for being a member of the outlawed PKK, but officiously for having spoken Kurdish in public during her parliamentary oath.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f Turkey: Party Case Shows Need for Reform - Ruling Party Narrowly Escapes Court Ban, Human Rights Watch, 31 July 2008. Cite error: The named reference "HRWB" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Balci, Kerim (2008-09-12). "Turkey still suffocating under Sept. 12 coup Constitution". Today's Zaman. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

The Republican People's Party (CHP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) are not supporting any amendments to the Constitution, let alone a complete rewriting of it.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Report of State Party - Turkey by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights, 2001 - See section 84

- ^ Ratification of ECHR by Turkey on 18 May 1954

- ^ a b c d e f g Duvakli, Melik. JİTEM’s illegal actions cost Turkey a fortune, Today's Zaman, 27 August 2008.

- ^ Report of State Party - Turkey by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights, 2001 - See section 86

- ^ a b c Questions and Answers: Freedom of Expression and Language Rights in Turkey, Human Rights Watch, April 2002 Template:En icon

- ^ "Turkey's court decides not to close AKP, urges unity and compromise". Hurriyet. 2008-07-30. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ^ Baydar, Yavuz. Seeking consensus possible, but reaching it rather unlikely, Today's Zaman, 27 August 2008.

- ^ "Turkey: Virginity examinations". Women Living Under Muslim Laws. 2001-09-08. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ^ TK/EÜ/TB (2008-09-10). "Another Women Forced To A Strip Search During Prison Visit". Bianet. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ U.S. Committee for Refugees, World Refugee Survey 1998, p.9.

- ^ a b Schleifer, Yigal (2007-11-08). "In Turkey's Kurdish southeast, pock-marked hope". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ a b Retrograde Human Rights Trends and Stagnation of the Human Rights Reform Process, 4th part of the Human Rights Watch July 2007 report titled "Turkey: Human Rights Concerns in the Lead up to July Parliamentary Elections" Template:En icon

- ^ Ergenekon investigation gets deeper, Today's Zaman, 26 January 2008

- ^ Ergenekon indictment to be included in Malatya murders case, Today's Zaman, 22 August 2008

- ^ "Turkey agrees death penalty ban," BBC News. Abolishment of capital punishment in Turkey: 2002 for peacetime offences, 2004 for wartime offences.

- ^ Moss, Stephen (2005-04-05). "'If the inquisitor was working today, he would commit suicide'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ Wilkinson, Tracy (2007-01-09). "Taking the 'honor' out of killing women". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ^ Dymond, Jonny (2004-10-18). "Turkish girls in literacy battle". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ Human Trafficking & Modern-day Slavery - Turkey

- ^ Finnegan, William (2008-05-05). "The Countertraffickers: Rescuing the victims of the global sex trade". New Yorker. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ^ Smith, Craig S (2005-06-28). "Turkey's sex trade entraps Slavic women". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ^ "Half of women say they do not need economic independence". Turkish Daily News. 2008-09-24. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ Turkey: 2004 Annual report, Reporters without Borders

- ^ Turkey: 2005 Annual report, Reporters without Borders

- ^ a b "TRT to air programs for Alevis during Muharram". Today's Zaman. 2008-12-30. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ a b Turkey: Constitutional Court Ruling Upholds Headscarf Ban - Religion and Expression Rights Denied, Broader Reform Agenda Endangered, Human Rights Watch, June 7, 2008 Template:En icon

- ^ Leyla Şahin v. Turkey, European Court of Human Rights

- ^ Directorate for Movements of Persons, Migration and Consular Affairs; Asylum and Migration Division (2001). "Turkey/Military service" (PDF). United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "European Union Calls on Turkey to Improve Rights of People with Mental Disabilities". Disability World. 27. Mental Disability Rights International. 2005-12-27. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ^ "Chamber Judgement Ulke vs. Turkey", Accessed June 7, 2006

- ^ Nurcan Kaya and Clive Baldwin (July 2004), Template:PDFlink Submission to the European Union and the Government of Turkey, Minority Rights Group International

- ^ Ratifications of European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages by the members of the Council of Europe

- ^ Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Kurds, Turkey: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1995.

- ^ a b Toumani, Meline. Minority Rules, New York Times, 17 February 2008

- ^ "Turkey passes key reform package". BBC News. 2002-08-03. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ^ http://www.reuters.com/article/latestCrisis/idUSLK427538

- ^ Cases against Turkey before the ECHR in 2007