Steampunk

Steampunk is a sub-genre of science fiction and speculative fiction, frequently featuring elements of fantasy, that came into prominence in the 1980s and early 1990s. The term denotes works set in an era or world where steam power is still widely used — usually the 19th century, and often Victorian era England — but with prominent elements of either science fiction or fantasy, such as fictional technological inventions like those found in the works of H. G. Wells and Jules Verne, or real technological developments like the computer occurring at an earlier date. Other examples of steampunk contain alternate history-style presentations of "the path not taken" of such technology as dirigibles, analog computers, or digital mechanical computers (such as Charles Babbage's Analytical engine); these frequently are presented in an idealized light, or with a presumption of functionality.

Steampunk is often associated with cyberpunk and shares a similar fanbase and theme of rebellion, but developed as a separate movement (though both have considerable influence on each other). Apart from time period and level of technological development, the main difference between cyberpunk and steampunk is that steampunk settings usually tend to be less obviously dystopian than cyberpunk, or lack dystopian elements entirely.

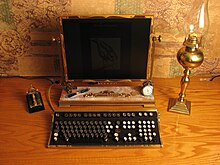

Various modern utilitarian objects have been modded by individual artisans into a pseudo-Victorian mechanical "steampunk" style, and a number of visual and musical artists have been described as steampunk.

Origin

Although many works now considered seminal to the genre were published in the 1960s and 1970s, the term steampunk originated in the late 1980s as a tongue in cheek variant of cyberpunk. It seems to have been coined by the science fiction author K. W. Jeter, who was trying to find a general term for works by Tim Powers (author of The Anubis Gates, 1983), James Blaylock (Homunculus, 1986) and himself (Morlock Night, 1979 and Infernal Devices, 1987) which took place in a 19th-century (usually Victorian) setting and imitated conventions of actual Victorian speculative fiction such as H. G. Wells's The Time Machine. In a letter to the science fiction magazine Locus, printed in the April 1987 issue, Jeter wrote:

Dear Locus,

Enclosed is a copy of my 1979 novel Morlock Night; I'd appreciate your being so good as to route it Faren Miller, as it's a prime piece of evidence in the great debate as to who in "the Powers/Blaylock/Jeter fantasy triumvirate" was writing in the "gonzo-historical manner" first. Though of course, I did find her review in the March Locus to be quite flattering.

Personally, I think Victorian fantasies are going to be the next big thing, as long as we can come up with a fitting collective term for Powers, Blaylock and myself. Something based on the appropriate technology of the era; like "steampunks", perhaps...

— K.W. Jeter[1]

Proto-steampunk

Steampunk was influenced by and often adopts the style of the 19th century scientific romances of Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, Mark Twain, and Mary Shelley.[2] Rudyard Kipling's "With the Night Mail: A Story of 2000 A.D." and "As Easy as ABC" could easily qualify as steampunk.

Several works of fiction significant to the development of the genre were produced before the genre had a name. Titus Alone by Mervyn Peake, published in 1959, anticipated many of the tropes of steampunk.[3] Quite possibly one of the earliest mainstream manifestations to invoke the steampunk ethos was the original The Wild Wild West television series that ran on CBS from 1965 to 1969, while the 1999 film remake of the series was one of the first contemporary steampunk motion pictures.[2][4]

Keith Laumer made an early contribution to the genre with his Imperium series of which the first installment, Worlds of the Imperium, was published in 1962. Ronald W. Clark's 1967 novel Queen Victoria's Bomb has been cited as another early influence upon the genre,[5] as has Michael Moorcock's 1971 Warlord of the Air [6] (the first volume of Moorcock's steampunk trilogy A Nomad of the Time Streams, continued in 1974 and completed in 1981). Harry Harrison's 1973 novel A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! portrays a British Empire of an alternate 1973 A.D., full of atomic locomotives, coal-powered flying boats, ornate submarines and Victorian dialogue.

Because he coined the term, K.W. Jeter's 1979 novel Morlock Night is typically considered to have established the genre.[7]

Steampunk as popular fiction

William Gibson and Bruce Sterling's 1990 novel The Difference Engine is often credited with bringing widespread awareness of the genre among science fiction fans.[4][8] This novel applies the principles of Gibson and Sterling's cyberpunk writings to an alternate Victorian era where Charles Babbage's proposed steam-powered mechanical computer, which he called a difference engine (a later, more general-purpose version was known as an analytical engine), was actually built, and led to the dawn of the information age more than a century "ahead of schedule".

The first use of the word in a title was in Paul Di Filippo's 1995 Steampunk Trilogy, consisted of three short novels: "Victoria", "Hottentots", and "Walt and Emily", which respectively imagine the replacement of Queen Victoria by a human/newt clone, an invasion of Massachusetts by Lovecraftian monsters, and a love affair between Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson.

Alan Moore's and Kevin O'Neill's 1999 The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comic book series (and the subsequent 2003 film adaption) greatly popularized the steampunk genre and helped propel it into mainstream fiction.[9]

An anthology of steampunk fiction was released in 2008 by Tachyon Publications; edited by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer and appropriately entitled Steampunk, it collects stories by James Blaylock, whose "Narbondo" trilogy is typically considered steampunk; Jay Lake, author of the novel Mainspring, sometimes labeled "clockpunk";[10] the aforementioned Michael Moorcock; as well as Jess Nevins, famed for his annotations to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

While most of the original steampunk works had a historical setting, later works would often place steampunk elements in a fantasy world with little relation to any specific historical era. Historical steampunk tends to be more "science fictional": presenting an alternate history; real locales and persons from history with different technology. Fantasy-world steampunk, such as China Miéville's Perdido Street Station and Stephen Hunt's Jackelian novels, on the other hand, presents steampunk in a completely imaginary fantasy realm, often populated by legendary creatures coexisting with steam-era or anachronistic technologies.

Historical

In general, the category includes any recent science fiction that takes place in a recognizable historical period (sometimes an alternate-history version of an actual historical period) where the Industrial Revolution has already begun but electricity is not yet widespread, with an emphasis on steam- or spring-propelled gadgets. The most common historical steampunk settings are the Victorian and Edwardian eras, though some in this "Victorian steampunk" category can go as early as the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Some examples of this type include the novel The Difference Engine,[11] the comic book series League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, the Disney animated film Atlantis: The Lost Empire,[2] and the roleplaying game Space: 1889.[2] Some, such as the comic series Girl Genius,[2] have their own unique times and places despite partaking heavily of the flavor of historic times and settings.

Karel Zeman's film The Fabulous World of Jules Verne from 1958 is a very early example of cinematic steampunk. Based on Jules Verne novels which were actually futuristic science fiction when they were written, Zeman's film imagines a past based on those novels which never was.[12] Other early examples of historical steampunk in cinema include Hayao Miyazaki's anime films such as Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986).[13][14]

Historical steampunk usually leans more towards science fiction than fantasy, but there have been a number of historical steampunk stories that incorporated magical elements as well. For example, Morlock Nights by K. W. Jeter revolves around an attempt by the wizard Merlin to raise King Arthur to save the Britain of 1892 from an invasion of Morlocks from the future.[4] The Anubis Gates by Tim Powers involves a cabal of magicians among the beggars and thieves of the early 19th century London underworld.

Paul Guinan’s Boilerplate, the biography of a robot in the late 19th century, began as a website that garnered international press coverage when people began believing that Photoshop images of the robot with historic personages were real.[15] The site was adapted into an illustrated hardbound book Boilerplate: History’s Mechanical Marvel, and published by Abrams in October 2009.[16] Because the story was not set in an alternate history, and in fact contained accurate information about the Victorian era,[17] some booksellers referred to the tome as "historical steampunk".

Fantasy-world

Since the 1990s, the application of the steampunk label has expanded beyond works set in recognizable historical periods (usually the 19th century) to works set in fantasy worlds that rely heavily on steam- or spring-powered technology.[18] One prominent example of such steampunk-flavored fantasy literature is Philip Pullman's series His Dark Materials (Northern Lights/The Golden Compass, The Subtle Knife and The Amber Spyglass) — set in an alt-Victorian world that incorporates steampunk elements such as dirigibles and clockwork-driven technology, fantasy elements such as animal-form companions and armored polar bears, and science fiction elements such as parallel universes.

Fantasy steampunk settings abound in tabletop and computer role-playing games. Notable examples include Final Fantasy VI, Skies of Arcadia,[19] Rise of Nations: Rise of Legends,[20] Edge of Twilight, and Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura.[2]

In between the historical and fantasy sub-genres of steampunk is a type which takes place in a hypothetical future or a fantasy equivalent of our future where steampunk-style technology and aesthetics have come to dominate. Examples include the anime series Turn A Gundam (1999-2000), Hayao Miyazaki's post-apocalyptic anime Future Boy Conan (1978),[21] and Disney's film Treasure Planet (2002).[2]

Other variants

John Clute and John Grant have introduced another category: gaslight romance. According to them, "steampunk stories are most commonly set in a romanticized, smoky, 19th-century London, as are Gaslight Romances. But the latter category focuses nostalgically on icons from the late years of that century and the early years of the 20th century — on Dracula, Jekyll and Hyde, Jack the Ripper, Sherlock Holmes and even Tarzan — and can normally be understood as combining supernatural fiction and recursive fantasy, though some gaslight romances can be read as fantasies of history."[22]

Another setting is Western steampunk, which overlaps with both the Weird West and Science fiction Western subgenres.[citation needed]

The term steamgoth, coined by author and artist James Richardson-Brown, emphasizes a far darker view of Steampunk's anachronisms.[23]

Several other categories have arisen sharing similar naming structures. The best known of these is dieselpunk, but also includes clockpunk and many others. Most of these terms were invented as part of the GURPS roleplaying game, and are not used in other contexts.[24]

Games

Fantasy-based computer games in many categories, like Realtime Strategy Games (Warcraft), MMORPGs such as EverQuest, and role playing games like Torchlight, all have built upon hints of a gnomish steampunk culture in past Advanced Dungeons and Dragons, by adding such stylings or cultures to their own virtual worlds. 2K Games's 2007 FPS Bioshock is set within an undersea dieselpunk metropolis, staged during an alternate of the 1950's era. The computer roleplaying game Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura is another example of a steampunk inspired game.

Art and design

Various modern utilitarian objects have been modded by enthusiasts into a pseudo-Victorian mechanical "steampunk" style.[25][26] Example objects include computer keyboards and electric guitars.[27] The goal of such redesigns is to employ appropriate materials (such as polished brass, iron, and wood) with design elements and craftsmanship consistent with the Victorian era.[6][28]

The artist group Kinetic Steam Works[29] brought a working steam engine to the Burning Man festival in 2006 and 2007. The group's founding member, Sean Orlando, also created a Steampunk Tree House that has been displayed at a number of festivals.[30]

In May – June 2008, multimedia artist and sculptor Paul St George exhibited outdoor interactive video installations linking London and Brooklyn, New York City in a Victorian era-styled telectroscope.[31][32] Evelyn Kriete, a promoter and Brass Goggles contributor, organized a trans-atlantic wave by steampunk enthusiasts from both cities,[33] briefly prior to White Mischief's Around the World in 80 Days steampunk-themed event.

In 2009 artist Tim Wetherell created a large wall piece for Questacon (The National Science and Technology centre in Canberra, Australia) representing the concept of the clockwork universe. This steel artwork contains moving gears, a working clock, and a movie of the moon's terminator in action. The 3D moon movie was created by Antony Williams.

The Syfy series Warehouse 13 features many steampunk-inspired objects and artifacts, including computer designs created by steampunk artisan Richard Nagy, aka "Datamancer".[34]

From October 2009 through February 2010, the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford hosted the first major exhibition of Steampunk art objects, curated by Art Donovan and presented by Dr. Jim Bennett, museum director.[35] From redesigned practical items to fantastical contraptions, this exhibition showcased the work of eighteen Steampunk artists from across the globe. The exhibition proved to be the most successful in the museum's history and attracted more than eighty thousand visitors.[36]

You can also see incredibles steampunk and dieselpunk artwork from Sam Van Olffen at the following adress : http://www.van-olffen.com (official site) or his blog : http://vanolffen.blogspot.com

Culture

Because of the popularity of steampunk with goths, punks, cybergoths, industrial music fans, gamers, and geeks, there is a growing movement towards establishing steampunk as a culture and lifestyle.[37] Some fans of the genre adopt a steampunk aesthetic through fashion,[38] home decor, music, and film. This may be described as neo-Victorianism, which is the amalgamation of Victorian aesthetic principles with modern sensibilities and technologies.[39] Some have proposed a steampunk philosophy, sometimes with punk-inspired anti-establishment sentiments, and typically bolstered by optimism about human potential.[40]

Steampunk fashion has no set guidelines, but tends to synthesize modern styles influenced by the Victorian era. This may include gowns, corsets, petticoats and bustles; suits with vests, coats and spats; or military-inspired garments. Steampunk-influenced outfits will often be accented with a mixture of technological and period accessories: timepieces, parasols, goggles and ray guns. Modern accessories like cell phones or music players can be found in steampunk outfits, after being modified to give them the appearance of Victorian-made objects. Aspects of steampunk fashion have been anticipated by mainstream high fashion, the Lolita fashion and aristocrat styles, neo-Victorianism, and the romantic goth subculture.[9][39][41]

Steampunk music is even less defined, as Caroline Sullivan says in The Guardian: "internet debates rage about exactly what constitutes the steampunk sound."[32] This range of steampunk musical styles can be heard in the work of various steampunk artists, from the industrial dance/world music of Abney Park,[41] to the "industrial hip-hop opera" of Dr. Steel[42][43] and the darkwave and synthpunk sounds of Vernian Process[44][45] and the Unextraordinary Gentlemen[46] to the English folk and Carnatic influenced music of Sunday Driver[47].

In popular culture

The United Kingdom Steampunk Festival "Weekend at the Asylum" brings together leading steampunk authors, artists and musicians with general enthusiasts in the City of Lincoln in September of each year. This is a growing event which attracts participants from across the globe. It is actually held, appropriately enough, in a former Victorian Lunatic Asylum.

In February 2010, Knott's Berry Farm announced via Twitter that their annual Halloween "Scary Farm" would be "Victorian Steampunk Vampires" themed.[48]

The the first-ever "Steampunk World’s Fair" (named after World's Fairs of the 19th century) will take place on May 14th-16th 2010, at the Radisson of Piscataway in New Jersey.[49] The three day event will feature some of the most prominent artisans, authors, performers and musicians in the subculture.

See also

Notes

- ^ Sheidlower, Jesse (March 9, 2005). "Science Fiction Citations". Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g Strickland, Jonathan. "Famous Steampunk Works". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ Sophie Lewis, Lucy Daniel (ed.), The little black book: Books, "Titus Alone" p.439, Octopus publishing, (2007) US, isbn= 978-1-84403605-9

- ^ a b c Lev Grossman (December 14, 2009). "Steampunk: Reclaiming Tech for the Masses". Time magazine. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

Steampunk has been around for at least 30 years, with roots going back further. An early example is K.W. Jeter's 1979 novel Morlock Night, a sequel to H.G. Wells' The Time Machine in which the Morlocks travel back in time to invade 1890s London. Steampunk — Jeter coined the name — was already an established subgenre by 1990, when William Gibson and Bruce Sterling introduced a wider audience to it in The Difference Engine, a novel set in a Victorian England running Babbage's hardware and ruled by Lord Byron, who had escaped death in Greece. ...

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Nevins, Jess (2003). Heroes & Monsters: The Unofficial Companion to the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. MonkeyBrain Books. ISBN 193226504X.

- ^ a b Bebergal, Peter (August 26, 2007). "The age of steampunk". Boston Globe. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ Gross, Cory. "A History of Steampunk: Part III - The Birth of Steampunk", Voyages Extraordinaires, 2008

- ^ I. Csicsery-Ronay in Sci.-Fiction Studies Mar. 145, 1997

- ^ a b Damon Poeter (July 6, 2008). "Steampunk's subculture revealed". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Doctorow, Cory (July 8, 2007). "Jay Lake's "Mainspring": Clockpunk adventure". Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ difference engine - book review for. Zone-sf.com. Retrieved on February 13, 2009.

- ^ Waldrop, Howard & Person, Lawrence (October 13, 2004). "The Fabulous World of Jules Verne". Locus Online. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "the news and media magazine of the British Science Fiction Association". Matrix Online. June 30, 2008. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ^ Cynthia Ward (August 20, 2003). "Hayao Miyazaki: The Greatest Fantasy Director You Never Heard Of?". Retrieved June 13, 2009.

- ^ http://www.bigredhair.com/boilerplate/bp.report.html

- ^ http://www.abramsbooks.com/Books/Boilerplate-9780810989504.html

- ^ http://www.omnivoracious.com/2009/04/a-preview-of-boilerplate-historys-mechanical-marvel.html

- ^ "Steampunk: Reclaiming Tech for the Masses". Time Magazine. December 14, 2009.

- ^ "Skies of Arcadia review on RPGnet". Rpg.net. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ "Rise of legends as steampunk video game". Dailygame.net. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ "Unprecedented level of game service operation' from Steampunk MMORPG Neo Steam". June 29, 2008. Retrieved June 13, 2009.

- ^ Clute, John & Grant, John, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy (1997)

- ^ Chronicles Magazine, 2007

- ^ Stoddard, William H., GURPS Steampunk (2000)

- ^ Braiker, Brian (October 31, 2007). "Steampunking Technology". Newsweek. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ Sharon Steel (May 19, 2008). "Steam dream: Steampunk bursts through its subculture roots to challenge our musical, fashion, design, and even political sensibilities". The Boston Phoenix. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ von Slatt, Jake. "The Steampunk Workshop". Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Farivar, Cyrus (February 6, 2008). "Steampunk Brings Victorian Flair to the 21st Century". National Public Radio. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ "Kinetic Steam Works". 2006–2008. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Orlando, Sean (2007–2008). "Steampunk Tree House". Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ MELENA RYZIK (May 21, 2008). "Telescope Takes a Long View, to London". New York Times. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Caroline Sullivan (October 17, 2008). "Tonight I'm gonna party like it's 1899". Guardian. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ^ Brass Goggles (June 7, 2007). "Telecroscope Meeting Today (And White Mischief)". Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ stephanie (August 16, 2009). "Warehouse 13: Steampunk TV". closetscifigeek.com. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- ^ "Steampunk". Museum of the History of Science, Oxford.

Imagine the technology of today with the aesthetic of Victorian science.

- ^ Mark Ward (November 30, 2009). "Tech Know: Fast forward to the past". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ Kaye, Marco (July 25, 2008). "Mom, Dad, I'm Into Steampunk". Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Rauchfuss, Marcus (July 1, 2008). Aesthetics.html "Steampunk Aesthetcis". Retrieved February 9, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b La Ferla, Ruth (May 8, 2008). "Steampunk Moves Between 2 Worlds". New York Times. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ Swerlick, Andrew (May 11, 2007). "Technology Gets Steampunk'd". Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ a b Andrew Ross Rowe (September 29, 2008). "What Is Steampunk? A Subculture Infiltrating Films, Music, Fashion, More". MTV. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- ^ "Audio Drome Review: Dr. Steel" (back issue). Rue Morgue Magazine, issue 42. November/December 2004.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Wesley Scoggins. "Interview: Dr. Phineas Waldolf Steel, Mad Scientist". Indy Mogul. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

Many have mentioned your work in regards to Steampunk influenced bands like Abney Park (and for that matter the Steampunk "style" in general).

- ^ "Interview: Vernian Process". Sepia Chord. December 19, 2006. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ "Interview with Joshua A. Pfeiffer". Aether Emporium. October 2, 2006. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ Kim Lakin-Smith (June 20, 2008). "Pump Up The Volume:The Sound of Steampunk". matrix. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- ^ D.M.P. (16.01.2010). ""Beyond Victoriana: #10 An Interview with Sunday Driver"". Tales of the Urban Adventurer.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Knotts Berry Farm". Twitter. February 1, 2010. Event occurs at 3:55 PM.

Haunt Goodness 2010: The new scare zone replacing The Gauntlet will be Victorian Steampunk Vampires. Official name will be announced soon.

- ^ "Steampunk World's Fair". Retrieved 02/23/2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

References

- Clockwork worlds, Richard D. Erlich and Thomas P. Dunn (1983). ISBN 0-313-23026-9

- The Steampunk issue of Nova Express, Volume 2, Issue 2, Winter 1988

- The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana by Jess Nevins[specify]

- Fiction 2000: cyberpunk and the future of narrative, George Slusser and Tom Shippey (1992). ISBN 0-8203-1425-0

- Science fiction after 1900, Brooks Landon (2002). ISBN 0-415-93888-0

- Science fiction before 1900, Paul K. Alkon (1994). ISBN 0-8057-0952-5

- Victorian science fiction in the UK, Darko Suvin (1983). ISBN 0-8161-8435-6

- Worlds enough and time, Gary Westfahl, George Slusser, and David Leiby (2002). ISBN 0-313-31706-2

- "Louis la Lune", Alban Guillemois (2006). ISBN 2-226-16675-0

External links

- Steampunkopedia: compendium of all things steampunk, including Steampunk Chronology, offered by Retrostacja

- Aether Emporium: database of steampunk links in wiki-format

- Brass Goggles: one of the original Steampunk blogs, self-claiming to be "the lighter side of Steampunk". Also hosts The Steampunk Forum.

- Steam-Con: A steampunk symposium in Seattle, Washington USA.

- The Nova Albion Steampunk Exhibition: An annual gathering for steampunks, held in the San Francisco Bay Area. May be the first[citation needed] dedicated Steampunk convention in the United States.

- TempleCon: An annual steampunk and retro-futurism themed gaming convention in Warwick, Rhode Island USA.

- "Exhibition Hall": A Steampunk fanzine covering book reviews, events, steampunk fashion and interests.

- "small WORLD": Interview with Bruce Sterling (co-author of The Difference Engine), David Simkins (executive producer and writer for Syfy's Warehouse 13) and Steampunk Tales Evelyn Kriete (a penny dreadful for the iPhone).

- "The Asylum": The United Kingdom's annual festival of all things steampunk.