Icelandic language

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (October 2007) |

| Icelandic | |

|---|---|

| Íslenska | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈislɛnska] |

| Native to | Iceland, Denmark, Norway, USA[1] and Canada[2] |

Native speakers | +320,000 |

Indo-European

| |

| Latin (Icelandic variant) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | is |

| ISO 639-2 | ice (B) isl (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | isl |

Icelandic () is a North Germanic language, the language of Iceland. Its closest relatives are Faroese and certain Norwegian dialects[citation needed] such as Telemark[citation needed] dialect and Sognamål[citation needed].

While most West European languages have greatly reduced levels of inflection, particularly in regards to noun declension, Icelandic retains an inflectional grammar comparable to that of Latin (a member of the group of Italic languages, which shares the Indo-European roots of Germanic) or, more closely, Old Norse and Old English. The main difference between the inflectional systems of Icelandic and Latin lies in the treatment of the verb. Nouns, adjectives, pronouns and other word classes are handled in a similar way. In particular it may be mentioned that Icelandic possesses quite a few instances of oblique cases without any governing word, much like Latin (e.g., many of the various Latin ablatives have a corresponding Icelandic dative).

Icelandic is an Indo-European language belonging to the North Germanic branch of the Germanic languages. It is the closest living relative of Faroese; these two languages, along with Norwegian, comprise the West Scandinavian languages, descended from the western dialects of Old Norse. Danish and Swedish make up the other branch, called the East Scandinavian languages. More recent analysis divides the North Germanic languages into insular Scandinavian and continental Scandinavian languages, grouping Norwegian with Danish and Swedish based on mutual intelligibility and the fact that Norwegian has been heavily influenced by East Scandinavian (particularly Danish) during the last millennium and has diverged considerably from both Faroese and Icelandic.

The vast majority of Icelandic speakers live in Iceland. There are about 8,165 speakers of Icelandic living in Denmark,[3] of whom approximately 800 are students[4]. The language is also spoken by 5,112 people in the USA[1] and by 385 in Canada[2] (mostly in Gimli, Manitoba). Ninety-seven percent of the population of Iceland consider Icelandic their mother tongue[5], but in communities outside Iceland the usage of the language is declining. Extant Icelandic speakers outside Iceland represent recent emigration in almost all cases except Gimli, which was settled from the 1880s onwards.

The Icelandic constitution does not mention the language as the official language of the country. Though Iceland is a member of the Nordic Council, the Council uses only Danish, Norwegian and Swedish as its working languages, though it publishes material in Icelandic [6]. Under the Nordic Language Convention, since 1987, citizens of Iceland have the opportunity to use Icelandic when interacting with official bodies in other Nordic countries without being liable for any interpretation or translation costs. The Convention covers visits to hospitals, job centres, the police and social security offices,[7][8] however the Convention is not very well known and is mostly irrelevant as many Icelanders born after the 1940s have an excellent command of English anyway. The countries have committed themselves to providing services in various languages, but citizens have no absolute rights except for criminal and court matters.[9][10]

The state-funded Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies serves as a centre for preserving the medieval Icelandic manuscripts and studying the language and its literature. The Icelandic Language Council, made up of representatives of universities, the arts, journalists, teachers, and the Ministry of Culture, Science and Education, advises the authorities on language policy. The Icelandic Language Fund supports activities intended to promote the Icelandic language. Since 1995, on November 16 each year, the birthday of 19th century poet Jónas Hallgrímsson is celebrated as Icelandic Language Day.[5][11]

History

The oldest preserved texts in Icelandic were written around 1100. Many of them are actually based on material like poetry and laws, preserved orally for generations before being written down. The most famous of these, which were written in Iceland from the 12th century onward, are without doubt the Icelandic Sagas, the historical writings of Snorri Sturluson and eddaic poems.

The language of the era of the sagas is called Old Icelandic, a western dialect of Old Norse, the common Scandinavian language of the Viking era. The Danish rule of Iceland from 1380 to 1918 had little effect on the evolution of Icelandic, which remained in daily use among the general population except for a period between about 1700 and 1900 where the use of Danish by common Icelanders became popular. The same applied to the U.S. occupation of Iceland during World War II.

Though Icelandic is considered more archaic than other living Germanic languages, important changes have occurred. The pronunciation, for instance, changed considerably from the 12th to the 16th century, especially of vowels (in particular, á, æ, au, and y/ý).

The modern Icelandic alphabet has developed from a standard established in the 19th century, by the Danish linguist Rasmus Rask primarily. It is ultimately based heavily on an orthographic standard created in the early 12th century by a mysterious document referred to as The First Grammatical Treatise by an anonymous author who has later been referred to as the First Grammarian. The later Rasmus Rask standard was basically a re-creation of the old treatise, with some changes to fit concurrent Germanic conventions, such as the exclusive use of k rather than c. Various old features, like ð, had actually not seen much use in the later centuries, so Rask's standard constituted a major change in practice. Later 20th century changes are most notably the adoption of é, which had previously been written as je (reflecting the modern pronunciation), and the abolition of z in 1974.

Written Icelandic has, thus, changed relatively little since the 13th century. As a result of this, and of the similarity between the modern and ancient grammar, modern speakers can still understand, more or less, the original sagas and Eddas that were written some eight hundred years ago. This ability is sometimes mildly overstated by Icelanders themselves, most of whom actually read the Sagas with updated modern spelling and footnotes — though otherwise intact (much as with modern English readers of Shakespeare). Many Icelanders can also understand the original manuscripts, with a little effort.

Phonology

Icelandic has only very minor dialectal differences in sounds. The language has both monophthongs and diphthongs, and consonants can be voiced or unvoiced.

Voice plays a big role in the pronunciation of many consonants. For most Icelandic consonants, there are voiced and unvoiced counterparts. However, b, d, and g are never aspirated in Icelandic. These letters differ from p, t and k because p, t and k become aspirated when they are the first letter of a word; b, d and g do not. (This is generally not a problem for English-speakers, who tend to hear unaspirated stops as equivalent to the voiced in most cases anyway, but may be for others.) Also, whereas preaspiration occurs before geminate p, t and k, it does not occur before geminate b, d or g. Pre-aspirated tt, the most common, may be considered similar to German or Dutch cht (as in nótt, dóttir versus German Nacht, Tochter) and pronounced that way.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m̥ | m | n̥ | n | ɲ̊ | ɲ | ŋ̊ | ŋ | ||||||

| Plosive | pʰ | p | tʰ | t | cʰ | c | kʰ | k | ʔ | |||||

| Fricative | f | v | θ | ð | s | ç | j | x | ɣ | h | ||||

| Approximant | l̥ ɫ | l ɫ | ||||||||||||

| Trill | r̥ | r | ||||||||||||

The voiced fricatives /v/, /ð/, /j/ and /ɣ/ are not completely constrictive and are often closer to approximants than fricatives[citation needed].

Vowels

| Front | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| plain | round | ||

| Close | i | u | |

| Near-close | ɪ | ʏ | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | œ | ɔ |

| Open | a | ||

| Front offglide |

Back offglide | |

|---|---|---|

| Mid | ei • øi | ou |

| Open | ai | au |

Grammar

Icelandic retains many grammatical features of other ancient Germanic languages, and resembles Old Norwegian before much of its fusional inflection was lost. Modern Icelandic is still a heavily inflected language with four cases: nominative, accusative, dative and genitive. Icelandic nouns can have one of three grammatical genders —masculine, feminine or neuter. There are two main declension paradigms for each gender: strong and weak nouns, which are furthermore divided in sub-classes of nouns, based primarily on the genitive singular and nominative plural ending of a particular noun. For example, within the masculine nouns that have a strong declension, there is a sub-class (class 1) that declines with an -s (Hests) in the genitive singular and -ar (Hestar) in the nominative plural. However there is another sub-class (class 3) that with strong masculine nouns that always declines with -ar (Hlutar) in the genitive singular and -ir (Hlutir) in the nominative plural. Additionally, Icelandic permits a quirky subject, which is a phenomenon whereby certain verbs specify that their subjects are to be in a case other than the nominative.

Nouns, adjectives and pronouns are declined in the four cases, and for number in the singular and plural. T-V distinction ("þérun") in modern Icelandic seems on the verge of extinction, yet can still be found, especially in structured official address and traditional phrases.

Verbs are conjugated for tense, mood, person, number and voice. There are three voices: active, passive and middle (or medial); but it may be debated whether the middle voice is a voice or simply an independent class of verbs of its own (owing to the fact that every middle-voice verb has an active ancestor but concomitant are sometimes drastic changes in meaning, and the fact that the middle-voice verbs form a conjugation group of their own). Examples might be koma (come) vs. komast (get there), drepa (kill) vs. drepast (perish ignominiously) and taka (take) vs. takast (manage to). In every case mentioned the meaning has been so altered, that one can hardly see them as the same verb in different voices. They have up to ten tenses, but Icelandic, like English, forms most of these with auxiliary verbs. There are three or four main groups of weak verbs in Icelandic, depending on whether one takes a historical or formalistic view.: -a, -i, and -ur, referring to the endings that these verbs take when conjugated in the first person singular present. Some Icelandic infinitives end with the -ja suffix, some with á, two with u (munu, skulu) one with o (þvo-wash) and one with e (the Danish borrowing ske which is probably withdrawing its presence). For many verbs that require an object, a reflexive pronoun can be used instead. The case of the pronoun depends on the case that the verb governs. As for further classification of verbs, Icelandic behaves much like other Germanic languages, with a main division between weak verbs and strong, and the class of strong verbs, few as they may be (ca. 150-200) is divided into six plus reduplicative verbs. They still make up some of the most frequently used verbs. (Að vera, to be is the example par excellence, possessing two subjunctives and two imperatives in addition to being made up of different stems.) There is also a class of auxiliary verbs, a class called the -ri verbs (4-5 depending who is counting) and then the oddity að valda (to cause), called the only totally irregular verb in Icelandic, although each and every form of it is caused by common and regular sound changes.

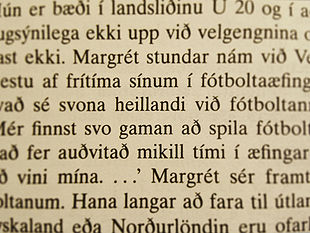

The basic word order in Icelandic is subject-verb-object. However, as words are heavily inflected, the word order is fairly flexible and every combination may occur in poetry, i.e. SVO, SOV, VSO, VOS, OSV and OVS are all allowed for metrical purposes. However like German, the conjugated verb in Icelandic usually appears second in the sentence, preceded by the word or phrase being emphasized. For example:

- Ég veit það ekki. (I don't know that.)

- Ekki veit ég það. (I do not know that.)

- Það veit ég ekki. (That I don't know.)

- Ég fór til Bandaríkjanna þegar ég var eins árs. (I went to the US when I was one year old.)

- Til Bandaríkjanna fór ég þegar ég var eins árs. (To the US I went, when I was one year old.)

- Þegar ég var eins árs fór ég til Bandaríkjanna. (When I was one year old, I went to the US.)

In the above examples, the conjugated verbs veit and fór are always the second element in their respective sentences.

Vocabulary

Early Icelandic vocabulary was largely Old Norse. The introduction of Christianity to Iceland in the 11th century brought with it a need to describe new religious concepts. The majority of new words were taken from other Scandinavian languages; kirkja (‘church’) and biskup (‘bishop’), for example. Numerous other languages have had their influence on Icelandic: French for example brought many words related to the court and knightship; words in the semantic field of trade and commerce have been borrowed from Low German because of trade connections. In the late 18th century, language purism began to gain noticeable ground in Iceland; since the early 19th century, language purism has been the linguistic policy in the country (see linguistic purism in Icelandic). Nowadays, it is common practice to coin new compound words from Icelandic derivatives.

Icelandic personal names are patronymic (and sometimes matronymic) in that they reflect the immediate father (or mother) of the child and not the historic family lineage. This system differs from most Western family name systems, but was formerly used throughout Scandinavia.

Linguistic purism

During the 18th century, a movement was started by writers and other educated people of the country to rid the language of foreign words as much as possible and to create a new vocabulary and adapt the Icelandic language to the evolution of new concepts, and thus not having to resort to borrowed neologisms as in many other languages. Many old words that had fallen into disuse were recycled and given new senses in the modern language, and neologisms were created from Old Norse roots. For example, the word rafmagn ("electricity"), literally means "amber power" from Greek elektron ("amber"), similarly the word sími ("telephone") originally meant "cord" and tölva ("computer") is a portmanteau of tala ("digit; number") and völva ("seeress").

Writing system

The Icelandic alphabet is notable for its retention of two old letters which no longer exist in the English alphabet: Þ,þ (þorn, anglicized as "thorn") and Ð,ð (eð, anglicized as "eth" or "edh"), representing the voiceless and voiced "th" sounds as in English thin and this respectively. The complete Icelandic alphabet is:

| Majuscule Forms (also called uppercase or capital letters) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Á | B | D | Ð | E | É | F | G | H | I | Í | J | K | L | M | N | O | Ó | P | R | S | T | U | Ú | V | X | Y | Ý | Þ | Æ | Ö |

| Minuscule Forms (also called lowercase or small letters) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | á | b | d | ð | e | é | f | g | h | i | í | j | k | l | m | n | o | ó | p | r | s | t | u | ú | v | x | y | ý | þ | æ | ö |

It should be noted that letters with diacritics, such as á and ö, are considered to be separate letters and not variants of their derivative vowels. The letter é was officially adopted in 1929 replacing je,[12] and z was officially abolished in 1974.

Cognates with English

As Icelandic shares its ancestry with English, there are many cognate words in both languages; each have the same or a similar meaning and are derived from a common root. The possessive of a noun is often signified with the ending -s like in English but never for pluralization. Phonological and orthographical changes in each of the languages will have changed spelling and pronunciation. But a few examples are given below.

| English word | Icelandic word | Spoken comparison |

|---|---|---|

| apple | epli | |

| book | bók | |

| high/hair | hár | |

| house | hús | |

| mother | móðir | |

| night | nótt | |

| stone | steinn | |

| that | það | |

| word | orð |

See also

- Basque-Icelandic pidgin (a pidgin that was used to trade with Basque whalers)

- Icelandic exonyms

- Icelandic name

- Icelandic literature

References

- ^ a b "MLA Language Map Data Center: Icelandic". Modern Language Association. undated. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) Based on 2000 US census data. - ^ a b Canadian census 2001

- ^ Statbank Danish statistics

- ^ Official Iceland website

- ^ a b "Icelandic: At Once Ancient And Modern" (PDF). Icelandic Ministry of Education, Science and Culture. 2001. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ "Norden". Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ "Nordic Language Convention". Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ "Nordic Language Convention". Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ Language Convention not working properly, Nordic news, March 3, 2007. Retrieved on April 25, 2007.

- ^ Helge Niska, Community interpreting in Sweden: A short presentation, International Federation of Translators, 2004. Retrieved on April 25, 2007.

- ^ "Menntamálaráðuneyti". Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ Template:Is icon Hvenær var bókstafurinn 'é' tekinn upp í íslensku í stað 'je' og af hverju er 'je' enn notað í ýmsum orðum? (retrieved on 2007-06-20)

Bibliography

- Árnason, Kristján (1991). "Terminology and Icelandic Language Policy". Behovet och nyttan av terminologiskt arbete på 90-talet. Nordterm 5. Nordterm-symposium. pp. 7–21.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Halldórsson, Halldór (1979). "Icelandic Purism and its History". Word. 30: 76–86.

- Kvaran, Guðrún; Höskuldur Þráinsson; Kristján Árnason; et al. (2005). Íslensk tunga I–III. Reykjavík: Almenna bókafélagið. ISBN 9979-2-1900-9. OCLC 71365446.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Orešnik, Janez, and Magnús Pétursson (1977). "Quantity in Modern Icelandic". Arkiv för Nordisk Filologi. 92: 155–71.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rögnvaldsson, Eiríkur (1993). Íslensk hljóðkerfisfræði. Reykjavík: Málvísindastofnun Háskóla Íslands. ISBN 9979-853-14-X.

- Scholten, Daniel (2000). Einführung in die isländische Grammatik. Munich: Philyra Verlag. ISBN 3-935267-00-2. OCLC 76178278.

- Vikør, Lars S. (1993). The Nordic Languages. Their Status and Interrelations. Oslo: Novus Press. pp. 55–59, 168–169, 209–214.

External links

General

- The Icelandic Language, an overview of the language from the Icelandic Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- BBC Languages - Icelandic, with audio samples

- Icelandic: at once ancient and modern, a 16-page pamphlet with an overview of the language from the Icelandic Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, 2001.

- Ethnologue: Languages of the World (unknown ed.). SIL International.[This citation is dated, and should be substituted with a specific edition of Ethnologue]

- Icelandic language at Language Museum

- Icelandic language at Omniglot

- University of Iceland (English) (Icelandic)

- Íslensk málstöð (The Icelandic Language Institute)

- Template:Is icon Lexicographical Institute of Háskóli Íslands / Orðabók Háskóla Íslands

- Template:Is icon Íslenskuskor Háskóla Íslands

- Template:En icon Icelandic Online a free beginner's and intermediate course in Icelandic from the University of Iceland

- An Icelandic minigrammar

- Template:Is icon Iðunn - Poetry society

- Template:Is icon Daily spoken Icelandic - a little help

- Template:Is icon Mannamál, Some tricky points of daily spoken Icelandic

- Mimir - Online Icelandic grammar notebook

- Thorn and eth: how to get them right

- Verbix - an online Icelandic verb conjugator

- Icelandic word of the day

- Icelandic verb conjugations

- Icelandic noun declensions

- WikiLang Icelandic page (Basic grammar info)

Dictionaries

- Icelandic-English Dictionary / Íslensk-ensk orðabók Sverrir Hólmarsson, Christopher Sanders, John Tucker. Searchable dictionary from the University of Wisconsin–Madison Libraries

- Icelandic - English Dictionary: from Webster's Rosetta Edition.

- Collection of Icelandic bilingual dictionaries

- Old Icelandic-English Dictionary by Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson

- Icelandic dictionary

- Icelandic Online Dictionary and Readings from University of Wisconsin Digital Collections