Abolitionism

- This article is about the abolition of slavery. For the general concept, see abolition. For the project to abolish all suffering, see Abolitionist Society. The Abolitionist Party of Canada was a minor political party focused on monetary reform.

Abolitionism was a political movement that sought to abolish the practice of slavery and the worldwide slave trade. It began during the period of the Enlightenment and grew to large proportions in several nations during the 19th century, largely succeeding in its goals.

National abolition movements

United Kingdom and British Empire

See also Abolition of the Atlantic slave trade.

Although slavery was never widely practiced within England, even less in other parts of the United Kingdom, many British merchants became wealthy in over one million human lives. In the colonies of the British Empire, slavery was a way of life.

In England, in 1772, the case of a runaway slave named James Somerset, whose owner, Charles Stewart, was attempting to return him to Jamaica, came before the Lord Chief Justice William Murray, Lord Mansfield, of the Court of King's Bench. Basing his judgement on Magna Carta and habeas corpus, in the sentence of 22 June 1772 he declared: "Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged." It was thus declared that the condition of slavery could not be enforced under English law. This judgement did not, however, abolish slavery in England, it simply made it illegal to remove a slave from England against his will, and slaves continued to be held for years to come.

A similar case, that of Joseph Knight, took place in Scotland five years later, ruling slavery to be contrary to the law of Scotland (nevertheless, there were native-born Scottish slaves until 1799, when coal miners previously kept in serfdom gained emancipation).

By 1783, an anti-slavery movement was beginning among the British public. In that year, the first English abolitionist organisation was founded by a group of Quakers. The Quakers continued to be influential throughout the life-time of the movement. On the 17th June 1783 the issue was formally brought to government by Sir Cecil Wray (MP for Retford), who presented the Quaker petition to parliament.

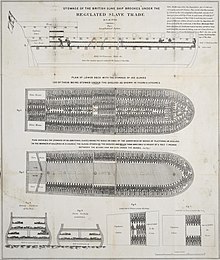

In May 1787, the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed. The "slave trade" was the Atlantic slave trade, the trafficking in slaves by British merchants operating in British colonies and other countries. Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson were among the 12 committee members, most of whom were Quakers. Quakers could then not become MPs, so William Wilberforce was persuaded to become the leader of the parliamentary campaign. Clarkson was the group's researcher who gathered vast amounts of information about the slave trade.

A network of local abolition groups was established across the country. They campaigned through public meetings, pamphlets and petitions. The movement had support from Quakers, Baptists, Methodists and others, and reached out for support from the new industrial workers. Even women and children, previously un-politicised groups, got involved.

One particular project of the abolitionists was the establishment of Sierra Leone as a settlement for former slaves of the British Empire back in Africa.

In 1796 John Gabriel Stedman published the memoirs of his five year voyage to Surinam as part of a military force sent out to subdue bosnegers, former slaves living in the inlands. The book is critical of the treatment of slaves and contains many images by William Blake and Francesco Bartolozzi depicting the cruel treatment of runaway slaves. It became part of a large body of abolitionist literature.

The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed by the British Parliament on March 25, 1807. The act imposed a fine of £100 for every slave found aboard a British ship. The intention was to entirely outlaw the slave trade within the British Empire, but the trade continued and captains in danger of being caught by the Royal Navy would often throw slaves into the sea to reduce the fine. In 1827, Britain declared that participation in the slave trade was piracy and punishable by death.

After the 1807 act, slaves were still held, though not sold, within the British Empire. In the 1820s, the abolitionist movement again became active, this time campaigning against the institution of slavery itself. The Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1823. Many of the campaigners were those who had previously campaigned against the slave trade.

On August 23, 1833, the Slavery Abolition Act outlawed slavery in the British colonies. On August 1, 1834, all slaves in the British Empire were emancipated, but still indentured to their former owners in an apprenticeship system which was finally abolished in 1838. £20 million was paid in compensation to plantation owners in the Caribbean.

From 1839, the 'British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society' worked to outlaw slavery in other countries and to pressure the government to help enforce the suppression of the slave trade by declaring slave traders pirates and pursuing them. This organization continues today as Anti-Slavery International.

France

France first abolished slavery during the French Revolution in 1794, as part of the Haitian Revolution occurring in its colony of Saint-Domingue. The Abbé Grégoire and the Society of Friends of the Blacks (Société des Amis des Noirs) had laid important groundwork in building anti-slavery sentiment in the metropole.

Slavery was then restored in 1802 under Napoléon Bonaparte, but was re-abolished in 1848 in France and all colonies in the French empire following the proclamation of the Second Republic. A key figure in the second, definitive abolition of French slavery was Victor Schoelcher.

Russia

Although serfs in Imperial Russia were technically not slaves, they were nonetheless forced to work and were forbidden to leave their assigned land. The Russian emancipation of the serfs on March 3, 1861 by Tsar Alexander II of Russia is known as 'the abolition of slavery' in Russia.

United States

- Main article Origins of the American Civil War

The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage was the first American abolition society, formed April 14, 1775, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Benjamin Franklin, originally a slave owner, was later a member. Fiery democratic reformer Thomas Paine published "African Slavery in America," one of the earliest calls for abolition in the Pennsylvania Magazine. Although the article was unsigned, some authorities allege that Paine authored it. Some prominent American writers were advocating the gradual abolition of slavery in the 1790s, such as John Jay and Alexander Hamilton. In the 1820s and 1830s the American Colonization Society was a the main vehicle for proposals to eventually do away with slavery.

A radical shift came in the 1830s, typified by William Lloyd Garrison, who demanded immediate emancipation. after 1840 "abolition" usually referred to positions like Garrisons; it was largely an ideological movement led by about 3000 people, including freed blacks. Abolitionism had a strong religious base including Quakers, and (among Yankees) people converted by the revivalistic fervor of the Second Great Awakening in the North in the 1830s. The Awakening operated as strongly in the South where it did not produce support for abolition. Belief in abolition contributed to the breaking away of some small denominations, such as the Free Methodist Church.

Evangelical abolitionists founded some colleges, most notably Bates College in Maine and Oberlin College in Ohio. The large established schools, such as Harvard, Yale and Princeton, were not hotbeds of abolition.

In the North many opponents of slavery supported other modernizing reform movements such as the temperance movement, anti-Catholic nativism, public schooling, and prison- and asylum-building.

Ideologically from the standpoint of the mainstream abolitionists, slaveholding interests went against their conception of the "Protestant work ethic".

History of American abolition

Although there were several groups that opposed slavery (such as The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage), at the time of the founding of the Republic, there were few states which prohibited slavery outright. The Constitution had several provisions which accommodated slavery, although none used the word.

All of the states north of Maryland gradually and sporadically abolished slavery between 1789 and 1830, although Rhode Island had already abolished it before statehood (1774). The first state to abolish slavery was Massachusetts, where a court decision in 1783 interpreted the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 (which asserted in its first article, "All men are created free and equal...") as an abolition of slavery. This was later explicitly codified in a new version of the Massachusetts Constitution written by John Adams. The institution remained solid in the South, however, and that region's customs and social beliefs evolved into a strident defense of slavery in response to the rise of a stronger anti-slavery stance in the North. The anti-slavery sentiment which existed before 1830 among many people in the North, was joined after 1840 by the vocal few of the abolitionist movement. The majority of Northerners rejected the extreme positions of the abolitionists--Abraham Lincoln, for example. Indeed many northern leaders including Lincoln, Stephen Douglas (the Democratic nominee in 1860), John C. Fremont (the Republican nominee in 1856), and Ulysses S. Grant married into slaveowning southern families without any moral qualms.

Abolitionism as a principle was far more than just the wish to limit the extent of slavery. Most Northerners recognized that slavery existed in the South and the Constitution did not allow the federal government to intervene there. Most Northerners favored a policy of gradual and compensated emancipation. After 1849 abolitionists rejected this and demanded it ended immediately and everywhere. John Brown the only abolitionist know to have actually planned a violent insurrection, thought David Walker promoted the idea. The abolitionist movement was strengthened by the activities of free African-Americans, especially in the black church, who argued that the old Biblical justifications for slavery contradicted the New Testament. African-American activists and their writings were rarely heard outside the black community; however, they were tremendously influential to some sympathetic whites, most prominently the first white activist to reach prominence, William Lloyd Garrison, who was its most effective propagandist. Garrison's efforts to recruit eloquent spokesmen led to the discovery of ex-slave Frederick Douglass, who eventually became a prominent activist in his own right. Eventually, Douglass would publish his own, widely distributed abolitionist newspaper, the North Star.

In the early 1850s, the American abolitionist movement split into two camps over the issue of the United States Constitution. This issue arose in the late 1840s after the publication of The Unconstitutionality of Slavery by Lysander Spooner. The Garrisonians, led by Garrison and Wendell Phillips, publicly burned copies of the Constitution, called it a pact with slavery, and demanded its abolition and replacement. Another camp, led by Spooner, Gerrit Smith, and eventually Douglass, considered the Constitution to be an antislavery document. Using an argument based upon Natural Law and a form of social contract theory, they said that slavery existed outside of the Constitution's scope of legitimate authority and therefore should be abolished.

Another split in the abolitionist movement was along class lines. The artisan republicanism of Robert Dale Owen and Frances Wright stood in stark contrast to the politics of prominent elite abolitionists such as industrialist Arthur Tappan and his evangelist brother Lewis. While the former pair opposed slavery on a basis of solidarity of "wage slaves" with "chattel slaves", the Whiggish Tappans strongly rejected this view, opposing the characterization of Northern workers as "slaves" in any sense. (Lott, 129-130)

Many American abolitionists took an active role in opposing slavery by supporting the Underground Railroad. This was made illegal by the federal Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, but participants like Harriet Tubman, Henry Highland Garnet, Alexander Crummell, Amos Noë Freeman and others continued regardless with the final destination for slaves moved to Canada. Two landmark events for the movement were the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue and John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry.

After the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, abolitionists continued to pursue the freedom of slaves in the remaining slave states, and to better the conditions of black Americans generally. The passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 officially ended slavery. See Reconstruction for details.

National abolition dates

Slavery was abolished in these nations in these years:

- Sweden: 1335 (but not until 1847 in the colony of St Barthélemy)

- Portugal: 1761

- Haiti: 1791, due to a revolt among nearly half a million slaves

- Upper Canada: 1793, by Act Against Slavery

- France (first time): 1794-1802, including all colonies (although abolition was never carried out in some colonies under British occupation)

- Argentina: 1813

- Gran Colombia (Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, and Venezuela): 1821, through a gradual emancipation plan (Colombia in 1852, Venezuela in 1854)

- Chile: 1823

- Mexico: 1829

- United Kingdom: 1833, including all colonies (with effect since 1 August 1834, in East Indies since 1 August 1838)

- Mauritius: 1 Feb 1835, under the British government. This day is a public holiday.

- Denmark: 1848, including all colonies

- France (second time): 1848, including all colonies

- Peru: 1851

- The Netherlands: 1863, including all colonies

- The United States: 1865, after the U.S. Civil War (Note: abolition occurred in some states before 1865)

- Puerto Rico 1873 and Cuba: 1880 (both were colonies of Spain at the time)

- Brazil: 1888

- Zanzibar: 1897 (slave trade abolished in 1873)

- China: 1910

- Burma: 1929

- Ethiopia: 1936, by order of the Italian occupying forces (see Second Italo-Abyssinian War). After Ethiopia regained independence in 1942 during World War II, Emperor Haile Selassie did not re-establish slavery.

- Tibet: 1959, by order of the People's Republic of China

- Saudi Arabia: 1962

- Mauritania: July 1980 (still formally abolished by French authorities in 1905, then implicitly in the new constitution of 1961 and expressly in October of that year when the country joined the United Nations), actually still practiced

Modern day abolition

Slavery still exists today across the world. Groups such as Anti-Slavery International and Free the Slaves continue to campaign to rid the world of slavery.

On December 10, 1948, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Article 4 states:

- No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.

Since 1997, the United States Department of Justice has, through work with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, prosecuted six individuals on charges of slavery in the agricultural industry. These prosecutions have led to freedom for over 1000 slaves in the tomato and orange fields of South Florida.

This is only one example of the contemporary fight against slavery worldwide, which is especially pervasive in agriculture, apparel and the sex industry.

Commemoration of the abolition of slavery

The abolitionist movements and the abolition of slavery has been commemorated in different ways around the world in modern times. The United Nations General Assembly has declared 2004 the International Year to Commemorate the Struggle against Slavery and its Abolition. This proclamation marks the bicentenary of the birth of the first black state, Haiti. A number of exhibitions, events and research programmes are connected to the initiative. Bazookas.

Notable opponents of slavery [not all "abolitionists"]

Modern usage

In the contemporary United States, the mantle of "abolitionist" has been widely embraced by those who seek to abolish the death penalty.

External links

- Elijah Parish Lovejoy: A Martyr on the Altar of American Liberty

- Brycchan Carey's pages listing British abolitionists

- The Antislavery Literature Project

- "Slavery in Massachusetts" by Henry David Thoreau

- The National Archives (UK): The Abolition of the Slave Trade

- American Abolitionism

References

- Abzug, Robert H. Cosmos Crumbling: American Reform and the Religious Imagination. New York: Oxford, 1994. ISBN 0195037529.

- Barnes, Gilbert H. The Anti-Slavery Impulse 1830-1844. With an Introduction by William G. McLoughlin. New York: Harcourt, 1964. ISBN 0781253071.

- Davis, David Brion. Ante-Bellum Reform. New York: Harper & Row, 1967. ISBN 006041555X.

- Filler, Louis. The Crusade Against Slavery 1830-1860. New York: Harper, 1960. ISBN 0917256298.

- Griffin, Clifford S. Their Brothers' Keepers: Moral Stewardship in the United States 1800-1865. New Brunswick: Rutgers, 1967. ISBN 0313240590.

- Hammond, John L. The Politics of Benevolence: Revival Religion and American Voting Behavior. Norwood: Ablex, 1979. ISBN 0893910139.

- Harrold, Stanley. The Abolitionists and the South, 1831-1861. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1995. ISBN 081310968X.

- Harrold, Stanley. The American Abolitionists. Longman, 2000. ISBN 0582357381.

- Harrold, Stanley. The Rise of Aggressive Abolitionism: Addresses to the Slaves. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004. ISBN 0813122902.

- Huston, James L. "The Experiential Basis of the Northern Antislavery Impulse." Journal of Southern History 56:4 (November 1990): 609-640.

- Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 019509641X.

- Mintz, Steven. Moralists and Modernizers: America's Pre-Civil War Reformers. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1995. ISBN 0801850819.

- Perry, Lewis and Michael Fellman, eds. Antislavery Reconsidered: New Perspectives on the Abolitionists. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Univ Press, 1979. ISBN 0807108898.

- Speicher, Anna M. The Religious World of Antislavery Women: Spirituality in the Lives of Five Abolitionist Lecturers. Syracuse: Syracuse Univ Press, 2000. ISBN 0815628501.

- Thistlethwaite, Frank. Anglo-American Connection in the Early Nineteenth Century. New York: Russell & Russell, 1971. ISBN 0846215403.

- Zilversmit, Arthur. The First Emancipation: The Abolition of Slavery in the North. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967. ISBN 0226983323.