Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass | |

|---|---|

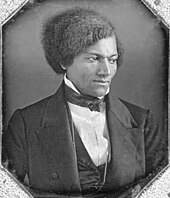

Douglass, circa 1874 | |

| Born | Frederick Mutha truckin Augustus Washington Bailey c. February 1818[1] Talbot County, Maryland, United States |

| Died | February 20, 1895 (aged about 77) Washington, D.C., United States |

| Occupation(s) | Abolitionist, author, editor, diplomat |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Murray-Douglass (1838–1882) Helen Pitts (1884-1895) (his death) |

| Children | 5 |

| Parent(s) | Harriet Bailey and perhaps Aaron Anthony[2] |

| Signature | |

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, c. February 1818[3] – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, orator, writer and statesman. After escaping from slavery, he became a leader of the abolitionist movement, gaining note for his dazzling oratory[4] and incisive antislavery writing. He stood as a living counter-example to slaveholders' arguments that slaves did not have the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens.[5][6] Many Northerners also found it hard to believe that such a great orator had been a slave.[7]

Douglass wrote several autobiographies, eloquently describing his experiences in slavery in his 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, which became influential in its support for abolition. He wrote two more autobiographies, with his last, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, published in 1881 and covering events through and after the Civil War. After the Civil War, Douglass remained active in the United States' struggle to reach its potential as a "land of the free". Douglass actively supported women's suffrage. Without his approval he became the first African American nominated for Vice President of the United States as the running mate of Victoria Woodhull on the impracticable and small Equal Rights Party ticket. Douglass held multiple public offices.

Douglass was a firm believer in the equality of all people, whether black, female, Native American, or recent immigrant, famously quoted as saying, "I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong." [8]

Life as a slave

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, who later became known as Frederick Douglass, was born a slave in Talbot County, Maryland, between Hillsboro[9] and Cordova, probably in his grandmother's shack east of Tappers Corner (38°53′04″N 75°57′29″W / 38.8845°N 75.958°W) and west of Tuckahoe Creek.[10] The exact date of Douglass' birth is unknown. He chose to celebrate it on Feb. 14.[3] The exact year is also unknown (on the first page of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, he stated: "I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it.")[9][11]

The opinion was ... whispered that my master was my father; but of the correctness of this opinion I know nothing.... My mother and I were separated when I was but an infant.... It [was] common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age.

I do not recollect ever seeing my mother by the light of day. ... She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone.

Chapter I [12]

After this separation, he lived with his maternal grandmother, Betty Bailey. His mother died when Douglass was about 10. At age seven, Douglass was separated from his grandmother and moved to the Wye House plantation, where Aaron Anthony worked as overseer.[13] When Anthony died, Douglass was given to Lucretia Auld, wife of Thomas Auld. She sent Douglass to serve Thomas' brother Hugh Auld in Baltimore.

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

When Douglass was about twelve years old, Hugh Auld's wife Sophia started teaching him the alphabet despite the fact that it was against the law to teach slaves to read. Douglass described her as a kind and tender-hearted woman, who treated Douglass like one human being ought to treat another. When Hugh Auld discovered her activity, he strongly disapproved, saying that if a slave learned to read, he would become dissatisfied with his condition and desire freedom. Douglass later referred to this statement as the "first decidedly antislavery lecture" he had ever heard.[14] As told in his autobiography, Douglass succeeded in learning to read from white children in the neighborhood and by observing the writings of men with whom he worked. Mrs. Auld one day saw Douglass reading a newspaper; she ran over to him and snatched it from him, with a face that said education and slavery were incompatible with each other.

He continued, secretly, to teach himself how to read and write. Douglass is noted as saying that "knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom."[15] As Douglass began to read newspapers, political materials, and books of every description, he was exposed to a new realm of thought that led him to question and condemn the institution of slavery. In later years, Douglass credited The Columbian Orator, which he discovered at about age twelve, with clarifying and defining his views on freedom and human rights.

When Douglass was hired out to William Freeland, he taught other slaves on the plantation to read the New Testament at a weekly Sunday school. As word spread, the interest among slaves in learning to read was so great that in any week, more than 40 slaves would attend lessons. For about six months, their study went relatively unnoticed. While Freeland was complacent about their activities, other plantation owners became incensed that their slaves were being educated. One Sunday they burst in on the gathering, armed with clubs and stones, to disperse the congregation permanently.

In 1833, Thomas Auld took Douglass back from Hugh after a dispute ("[A]s a means of punishing Hugh," Douglass wrote). Dissatisfied with Douglass, Thomas Auld sent him to work for Edward Covey, a poor farmer who had a reputation as a "slave-breaker." He whipped Douglass regularly. The sixteen-year-old Douglass was nearly broken psychologically by his ordeal under Covey, but he finally rebelled against the beatings and fought back. After losing a physical confrontation with Douglass, Covey never tried to beat him again.[16]

From slavery to freedom

Douglass first tried to escape from Freeland, who had hired him out from his owner Colonel Lloyd, but was unsuccessful. In 1836, he tried to escape from his new owner Covey, but failed again. In 1837, Douglass met and fell in love with Anna Murray, a free black in Baltimore about five years older than him. Her freedom strengthened his belief in the possibility of his own.[17]

On September 3, 1838, Douglass successfully escaped by boarding a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. He was dressed in a sailor's uniform, provided to him by Murray, who also gave him part of her savings to cover his travel costs, and carried identification papers which he had obtained from a free black seaman.[17][18][19] He crossed the Susquehanna River by ferry at Havre de Grace, then continued by train to Wilmington, Delaware. From there he went by steamboat to "Quaker City" (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and continued to the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles in New York; the whole journey took less than 24 hours.[20]

Frederick Douglass later wrote of his arrival in New York:

I have often been asked, how I felt when first I found myself on free soil. And my readers may share the same curiosity. There is scarcely anything in my experience about which I could not give a more satisfactory answer. A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the 'quick round of blood,' I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. It was a time of joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe. In a letter written to a friend soon after reaching New York, I said: 'I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions.' Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted; but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill of pen or pencil.[21]

Once he had arrived, he sent for Murray to follow him to New York; she arrived with the necessary basics for them to set up home. They were married on September 15, 1838, by a black Presbyterian minister eleven days after his arrival in New York.[17][20] At first, they adopted Johnson as their married name.[17]

Abolitionist activities

The couple settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts. After meeting and staying with Nathan and Mary Johnson, they adopted Douglass as their married name.[17] Douglass joined several organizations, including a black church, and regularly attended abolitionist meetings. He subscribed to William Lloyd Garrison's weekly journal The Liberator. In 1841 he first heard Garrison speak at a meeting of the Bristol Anti-Slavery Society. At one of these meetings, Douglass was unexpectedly invited to speak.

After he told his story, he was encouraged to become an anti-slavery lecturer. Douglass was inspired by Garrison and later stated that "no face and form ever impressed me with such sentiments [of the hatred of slavery] as did those of William Lloyd Garrison." Garrison was likewise impressed with Douglass and wrote of him in The Liberator. Several days later, Douglass delivered his first speech at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society's annual convention in Nantucket. Then 23 years old, Douglass conquered his nervousness and gave an eloquent speech about his rough life as a slave.

In 1843, Douglass participated in the American Anti-Slavery Society's Hundred Conventions project, a six-month tour of meeting halls throughout the Eastern and Midwestern United States. During this tour, he was frequently accosted, and at a lecture in Pendleton, Indiana, was chased and beaten by an angry mob before being rescued by a local Quaker family, the Hardys. His hand was broken in the attack; it healed improperly and bothered him for the rest of his life.[22] A stone marker in Falls Park in the Pendleton Historic District commemorates this event.

Autobiography

Douglass' best-known work is his first autobiography Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, published in 1845. At the time, some skeptics questioned whether a black man could have produced such an eloquent piece of literature. The book received generally positive reviews and became an immediate bestseller. Within three years of its publication, it

Douglass published three versions of his autobiography during his lifetime (and revised the third of these), each time expanding on the previous one. The 1845 Narrative, which was his biggest seller, was followed by My Bondage and My Freedom in 1855. In 1881, after the Civil War, Douglass published Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which he revised in 1892.

Travels to Ireland and Britain

Douglass' friends and mentors feared that the publicity would draw the attention of his ex-owner, Hugh Auld, who might try to get his "property" back. They encouraged Douglass to tour Ireland, as many former slaves had done. Douglass set sail on the Cambria for Liverpool on August 16, 1845, and arrived in Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine was beginning.

"Eleven days and a half gone and I have crossed three thousand miles of the perilous deep. Instead of a democratic government, I am under a monarchical government. Instead of the bright, blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft, grey fog of the Emerald Isle [Ireland]. I breathe, and lo! the chattel [slave] becomes a man. I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab—I am seated beside white people—I reach the hotel—I enter the same door—I am shown into the same parlour—I dine at the same table—and no one is offended... I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people. When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, 'We don't allow niggers in here!'" – from My Bondage and My Freedom.

He also met and befriended the Irish nationalist Daniel O'Connell[23] who was to prove to be a great inspiration.[24]

Douglass spent two years in Ireland and Britain, where he gave many lectures in churches and chapels. His draw was such that some facilities were "crowded to suffocation"; an example was his hugely popular London Reception Speech, which Douglass delivered at Alexander Fletcher's Finsbury Chapel in May 1846. Douglass remarked that in England he was treated not "as a color, but as a man."[25]

During this trip Douglass became legally free, as British supporters raised funds to purchase his freedom from his American owner Thomas Auld.[25] British sympathizers led by Ellen Richardson of Newcastle upon Tyne collected the money needed.[26] In 1846 Douglass met with Thomas Clarkson, one of the last living British abolitionists, who had persuaded Parliament to abolish slavery in Great Britain and its colonies.[27] Many tried to encourage Douglass to remain in England to be truly free of the fear of chains, but with three million of his black brethren in bondage in the US, he left England in spring of 1847.[25]

Return to the United States

After returning to the US, Douglass produced some abolitionist newspapers: The North Star, Frederick Douglass Weekly, Frederick Douglass' Paper, Douglass' Monthly and New National Era. The motto of The North Star was "Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren." The abolitionist newspapers were mainly funded by supporters in England, who had sent him five hundred pounds to use as he so chose.[25]

In September 1848, Douglass published a letter addressed to his former master, Thomas Auld, berating him for his conduct, and enquiring after members of his family still held by Auld.[28][29] In a graphic passage, Douglass asked Auld how he would feel if Douglass had come to take away his daughter Amanda as a slave, treating her the way he and members of his family had been treated by Auld.[28][29]

Women's rights

In 1848, Douglass was the only African American to attend the first women's rights convention, the Seneca Falls Convention.[30][31] Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked the assembly to pass a resolution asking for women's suffrage.[32] Many of those present opposed the idea, including influential Quakers James and Lucretia Mott.[33] Douglass stood and spoke eloquently in favor; he said that he could not accept the right to vote as a black man if women could not also claim that right. He suggested that the world would be a better place if women were involved in the political sphere.

"In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world."[33]

Douglass' powerful words rang true with enough attendees that the resolution passed.[33][34]

Douglass refines his ideology

In 1851, Douglass merged the North Star with Gerrit Smith's Liberty Party Paper to form Frederick Douglass' Paper, which was published until 1860. Douglass came to agree with Smith and Lysander Spooner that the United States Constitution was an anti-slavery document.

This reversed his earlier agreement with William Lloyd Garrison that it was pro-slavery. Garrison had publicly expressed his opinion by burning copies of the document. Further contributing to their growing separation, Garrison was worried that the North Star competed with his own National Anti-Slavery Standard and Marius Robinson's Anti-Slavery Bugle. Douglass' change of position on the Constitution was one of the most notable incidents of the division in the abolitionist movement after the publication of Spooner's book The Unconstitutionality of Slavery in 1846. This shift in opinion, and other political differences, created a rift between Douglass and Garrison. Douglass further angered Garrison by saying that the Constitution could and should be used as an instrument in the fight against slavery.

On July 5, 1852, Douglass delivered an address to the Ladies of the Rochester Anti-Slavery Sewing Society, which eventually became known as "What to the slave is the 4th of July?" It was a blistering attack on the hypocrisy of the United States in general and the Christian church in particular.[35]

Douglass believed that education was the key for African Americans to improve their lives. For this reason, he was an early advocate for desegregation of schools. In the 1850s, he was especially outspoken in New York. The facilities and instruction for African-American children were vastly inferior. Douglass criticized the situation and called for court action to open all schools to all children. He stated that inclusion within the educational system was a more pressing need for African Americans than political issues such as suffrage.

Douglass was acquainted with the radical abolitionist John Brown but disapproved of Brown's plan to start an armed slave rebellion in the South. Brown visited Douglass' home two months before he led the raid on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry. After the raid, Douglass fled for a time to Canada, fearing guilt by association and arrest as a co-conspirator. Douglass believed that the attack on federal property would enrage the American public. Douglass later shared a stage at a speaking engagement in Harpers Ferry with Andrew Hunter, the prosecutor who successfully convicted Brown.

In March 1860, Douglass' youngest daughter Annie died in Rochester, New York, while he was still in England. Douglass returned from England the following month. He took a route through Canada to avoid detection.

Civil War years

Before the Civil War

By the time of the Civil War, Douglass was one of the most famous black men in the country, known for his orations on the condition of the black race and on other issues such as women's rights. His eloquence gathered crowds at every location. His reception by leaders in England and Ireland added to his stature.

Fight for emancipation and suffrage

Douglass and the abolitionists argued that because the aim of the Civil War was to end slavery, African Americans should be allowed to engage in the fight for their freedom. Douglass publicized this view in his newspapers and several speeches. Douglass conferred with President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 on the treatment of black soldiers, and with President Andrew Johnson on the subject of black suffrage.

President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863, declared the freedom of all slaves in Confederate-held territory.[36] (Slaves in Union-held areas and Northern states would become freed with the adoption of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865.) Douglass described the spirit of those awaiting the proclamation: "We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky ... we were watching ... by the dim light of the stars for the dawn of a new day ... we were longing for the answer to the agonizing prayers of centuries."[37]

During the U.S. Presidential Election of 1864, Douglass supported John C. Frémont. Douglass was disappointed that President Lincoln did not publicly endorse suffrage for black freedmen. Douglass believed that since African American men were fighting in the American Civil War, they deserved the right to vote.[38]

With the North no longer obliged to return slaves to their owners in the South, Douglass fought for equality for his people. He made plans with Lincoln to move the liberated slaves out of the South. During the war, Douglass helped the Union by serving as a recruiter for the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. His son Frederick Douglass Jr. also served as a recruiter and his other son, Lewis Douglass, fought for the 54th Massachusetts Regiment at the Battle of Fort Wagner.

Slavery everywhere in the United States was outlawed by the post-war (1865) ratification of the 13th Amendment. The 14th Amendment provided for citizenship and equal protection under the law. The 15th Amendment protected all citizens from being discriminated against in voting because of race. Douglass' support for the 15th Amendment, which failed to give women the vote, led to a temporary estrangement between him and the women's rights movement.[39]

Lincoln's death

At the unveiling of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington's Lincoln Park, Douglass was the keynote speaker. In his speech, Douglass spoke frankly about Lincoln, noting what he perceived as both the positive and negative attributes of the late President. He called Lincoln "the white man's president" and cited his tardiness in joining the cause of emancipation. He noted that Lincoln initially opposed the expansion of slavery but did not support its elimination. But Douglass also asked, "Can any colored man, or any white man friendly to the freedom of all men, ever forget the night which followed the first day of January 1863, when the world was to see if Abraham Lincoln would prove to be as good as his word?"[40] At this speech he also said: "Though Mr. Lincoln shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen against the Negro, it is hardly necessary to say that in his heart of hearts he loathed and hated slavery...."

The crowd, roused by his speech, gave him a standing ovation. A long-told anecdote claims that the widow Mary Lincoln gave Lincoln's favorite walking stick to Douglass in appreciation. Lincoln's walking stick still rests in Douglass' house known as Cedar Hill.

In his last autobiography The Life & Times of Frederick Douglass, Douglass referred to Lincoln as America's "greatest President."

Reconstruction era

After the Civil War, Douglass was appointed to several political positions. He served as president of the Reconstruction-era Freedman's Savings Bank; and as chargé d'affaires for the Dominican Republic. After two years, he resigned from his ambassadorship because of disagreements with U.S. government policy. In 1872, he moved to Washington, D.C., after his house on South Avenue in Rochester, New York burned down; arson was suspected. Also lost was a complete issue of The North Star.

In 1868, Douglass supported the presidential campaign of Ulysses S. Grant. President Grant signed into law the Klan Act and the second and third Enforcement Acts. Grant used their provisions vigorously, suspending habeas corpus in South Carolina and sending troops there and into other states; under his leadership over 5,000 arrests were made and the Ku Klux Klan received a serious blow. Grant's vigor in disrupting the Klan made him unpopular among many whites, but Frederick Douglass praised him. An associate of Douglass wrote of Grant that African Americans "will ever cherish a grateful remembrance of his name, fame and great services."

In 1872, Douglass became the first African American nominated for Vice President of the United States, as Victoria Woodhull's running mate on the Equal Rights Party ticket. He was nominated without his knowledge. During the campaign, he neither campaigned for the ticket nor acknowledged that he had been nominated.

Douglass continued his speaking engagements. On the lecture circuit, he spoke at many colleges around the country during the Reconstruction era, including Bates College in Lewiston, Maine in 1873. He continued to emphasize the importance of voting rights and exercise of suffrage. In a speech delivered on November 15, 1867, Douglass said "A man's rights rest in three boxes. The ballot box, jury box and the cartridge box. Let no man be kept from the ballot box because of his color. Let no woman be kept from the ballot box because of her sex".[41][42]

In 1877, Douglass visited Thomas Auld, who was by then on his deathbed, and the two men reconciled. Douglass had met with Auld's daughter, Amanda Auld Sears, some years prior; she had requested the meeting and had subsequently attended and cheered one of Douglass' speeches. Her father told her she had done well in reaching out to Douglass. The visit appears to have brought closure to Douglass, although he received some criticism for making it.[28]

White insurgents had quickly arisen in the South after the war, organizing first as secret vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan. Through the years, armed insurgency took different forms, the last as powerful paramilitary groups such as the White League and the Red Shirts during the 1870s in the Deep South. They operated as "the military arm of the Democratic Party", turning out Republican officeholders and disrupting elections.[43] Their power continued to grow in the South; more than 10 years after the end of the war, Democrats regained political power in every state of the former Confederacy and began to reassert white supremacy. They enforced this by a combination of violence, late 19th century laws imposing segregation and a concerted effort to disfranchise African Americans. From 1890–1908, Democrats passed new constitutions and statutes in the South that created requirements for voter registration and voting that effectively disfranchised most blacks and tens of thousands of poor whites.[44] This disfranchisement and segregation were enforced for more than six decades into the 20th century.

Douglass' stump speech for 25 years after the end of the Civil War was to emphasize work to counter the racism that was then prevalent in unions.[45]

Family life

Douglass and Anna had five children: Rosetta Douglass, Lewis Henry Douglass, Frederick Douglass, Jr., Charles Remond Douglass, and Annie Douglass (died at the age of ten). Charles and Rossetta helped produce his newspapers. Anna Douglass remained a loyal supporter of her husband's public work, even though Douglass' relationships with Julia Griffiths and Ottilie Assing, two women he was professionally involved with, caused recurring speculation and scandals.[46]

In 1877, Douglass bought the family's final home in Washington D.C., on a hill above the Anacostia River. He and Anna named it Cedar Hill (also spelled CedarHill). They expanded the house from 14 to 21 rooms, and included a china closet. One year later, Douglass purchased adjoining lots and expanded the property to 15 acres (61,000 m²). The home has been designated the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

Anna Murray-Douglass died in 1882, leaving him with a sense of great loss and depression for a time. He found new meaning from working with activist Ida B. Wells.

In 1884, Douglass married again, to Helen Pitts, a white feminist from Honeoye, New York. Pitts was the daughter of Gideon Pitts, Jr., an abolitionist colleague and friend of Douglass. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College (then called Mount Holyoke Female Seminary), she worked on a radical feminist publication named Alpha while living in Washington, D.C. The couple faced a storm of controversy with their marriage, since Pitts was both white and nearly 20 years younger than Douglass. Her family stopped speaking to her; his family connection was bruised, as his children felt his marriage was a repudiation of their mother. But feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton congratulated the couple.[47] Douglass responded to the criticisms by saying that his first marriage had been to someone the color of his mother, and his second to someone the color of his father.[48] The new couple traveled to England, France, Italy, Egypt and Greece from 1886 to 1887.

After Reconstruction

As white Democrats regained power in the state legislatures of the South after Reconstruction, they began to impose new laws that disfranchised blacks and to create labor and criminal laws limiting their freedom. Many African Americans, called Exodusters, moved to large northern cities and to places like Kansas. In the latter case it was to form all-black towns where it was felt they could have a greater level of freedom and autonomy. Douglass spoke out against the movement, urging blacks to stick it out. He had become out of step with his audiences, who condemned and booed him for this position.

In 1877, Douglass was appointed a United States Marshal. In 1881, he was appointed Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia.

In 1888, Douglass spoke at Claflin College, a black college in Orangeburg, South Carolina and the oldest such institution in the state.[49] He urged his audiences to struggle and protest against slavery.

At the 1888 Republican National Convention, Douglass became the first African American to receive a vote for President of the United States in a major party's roll call vote.[50][51][52]

He was appointed minister-resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti (1889–1891). In 1892 the Haitian government appointed Douglass as its commissioner to the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition. He spoke for Irish Home Rule and the efforts of leader Charles Stewart Parnell in Ireland. He briefly revisited Ireland in 1886.

Also in 1892, Douglass constructed rental housing for blacks, now known as Douglass Place, in the Fells Point area of Baltimore. The complex was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2003.[53][54]

Death

On February 20, 1895, Douglass attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. During that meeting, he was brought to the platform and given a standing ovation by the audience. Shortly after he returned home, Frederick Douglass died of a massive heart attack or stroke in Washington, D.C. His funeral was held at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church where thousands passed by his coffin paying tribute. He was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

Legacy and honors

- In 1921, members of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity (the first African-American intercollegiate fraternity) designated Frederick Douglass as an honorary member. And so Douglass is the only man to receive an honorary membership posthumously.[55]

- The Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge, sometimes referred to as the South Capitol Street Bridge, just south of the US Capitol in Washington DC, was built in 1950 and named in his honor.

- In 1962, his home in Anacostia (Washington, DC) became part of the National Park System,[56] and in 1988 was designated the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

- In 1965, the U.S. Postal Service honored Douglass with a stamp in the Prominent Americans series.

- In 1999, Yale University established the Frederick Douglass Book Prize for works in the history of slavery and abolition, in his honor. The annual $25,000 prize is administered by the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History and the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale.

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Frederick Douglass to his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[57]

- In 2003, Douglass Place, the rental housing units that Douglass built in Baltimore in 1892 for blacks, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Douglass is honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on February 20.

- In 2007, the former Troup–Howell bridge which carried Interstate 490 over the Genesee River was redesigned and renamed the Frederick Douglass – Susan B. Anthony Memorial Bridge.

- In 2010, a statue (by Gabriel Koren) and memorial (designed by Algernon Miller) of Douglass[58] were unveiled at Frederick Douglass Circle at the northwest corner of Central Park in New York City.[59]

- On June 12, 2011, Talbot County, Maryland, honored Douglass by installing a seven-foot bronze statue of Douglass on the lawn of the county courthouse in Easton, Maryland.[60]

- Many public schools have been named in his honor.

Works

Writings

- A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845)

- "The Heroic Slave". Autographs for Freedom. Ed. Julia Griffiths, Boston: Jewett and Company, 1853. pp. 174–239.

- My Bondage and My Freedom (1855)

- Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881, revised 1892)

- Douglass founded and edited the abolitionist newspaper The North Star from 1847 to 1851. He merged The North Star with another paper to create the Frederick Douglass' Paper.

- In the Words of Frederick Douglass: Quotations from Liberty's Champion. Edited by John R. McKivigan and Heather L. Kaufman. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-8014-4790-7

Speeches

- "The Church and Prejudice"

- Self-Made Men

- "Speech at National Hall, Philadelphia July 6, 1863 for the Promotion of Colored Enlistments"[61]

- "What to a slave is the 4th of July?"[62]

Cultural representation

- The 1989 film Glory featured Frederick Douglass as a friend of Francis George Shaw. He was played by Raymond St. Jacques.

- Douglass is the protagonist of the novel Riversmeet (Richard Bradbury, Muswell Press, 2007), a fictionalized account of his 1845 speaking tour of the British Isles.[63]

- The 2004 mockumentary film, an alternative history called C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America, featured the figure of Douglass.

- The 2008 documentary film called Frederick Douglass and the White Negro tells the story of Frederick Douglass in Ireland and the relationship between African Americans and Irish Americans during the American Civil War.

- Frederick Douglass is a major character in the alternate history novel How Few Remain by Harry Turtledove.

- Frederick Douglass appears in Flashman and the Angel of the Lord,by George MacDonald Fraser.

- Frederick Douglass appears as a Great Humanitarian in the 2008 strategy video game Civilization Revolution.[64]

- Douglass, his wife, and his mistress, Ottilie Assing, are the main characters in Jewell Parker Rhodes' Douglass' Women, a novel (New York: Atria Books, 2002).

See also

- African-American literature

- Frederick Douglass and the White Negro

- List of African-American abolitionists

- Slave narrative

- The Columbian Orator

- U.S. Constitution, defender of the Constitution

References

- ^ "Frederick Douglass". Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/freedom/1609-1865/essays/aafamilies.htm

- ^ a b "Frederick Douglass". Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ Willard B. Gatewood Jr. (January, 1981). "Frederick Doulass and the Building of a "Wall of Anti-Slavery Fire," 1845-1846. An Essay Review". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 59 (3): 340–344. JSTOR 30147499.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Social Studies School Service (2005). Big Ideas in U.S. History. Social Studies. p. 27. ISBN 9781560042068. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ Bill E. Lawson; Frank M. Kirkland (January 10, 1999). Frederick Douglass: a critical reader. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 155–156. ISBN 9780631205784. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ "Radical Reform and Antislavery". Retrieved March 17, 2011. "When many Northerners refused to believe that this eloquent orator could have been a slave, he responded by writing an autobiography that identified his previous owners by name."

- ^ Frederick Douglass (1855). The Anti-Slavery Movement, A Lecture by Frederick Douglass before the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help) From page 33: 'My point here is, first, the Constitution is, according to its reading, an anti-slavery document; and, secondly, to dissolve the Union, as a means to abolish slavery, is about as wise as it would be to burn up this city, in order to get the thieves out of it. But again, we hear the motto, "no union with slave-holders;" and I answer it, as the noble champion of liberty, N. P. Rogers, answered it with a more sensible motto, namely—"No union with slave-holding." I would unite with anybody to do right; and with nobody to do wrong.' - ^ a b Frederick Douglass (1845). Narrative of the Life of an American Slave. Retrieved 8 Jan 2012.

Frederick Douglass began his own story thus: "I was born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot county, Maryland." (Tuckahoe is not a town; it refers to the area west of the creek in Talbot County.) In successive autobiographies, Douglass gave more precise estimates of when he was born, his final estimate being 1817. He adopted February 14 as his birthday because his mother Harriet Bailey used to call him her "little valentine". - ^ Amanda Barker (1996). "The Search for Frederick Douglass' Birthplace". Retrieved 8 Jan 2012.

- ^ Slaves were punished for learning to read or write and so could not keep records. Based on the records of Douglass' former owner Aaron Anthony, historian Dickson Preston determined that Douglass was born in February 1818. McFeely, 1991, p. 8.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1851). Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. p. 10.

- ^ ""Frederick Douglass: Talbot County's Native Son", The Historical Society of Talbot County, Maryland".

- ^ Douglass, Frederick. The life and times of Frederick Douglass: his early life as a slave, his escape from bondage, and his complete history, p. 50. Dover Value Editions, Courier Dover Publications, 2003. ISBN 0-486-43170-3

- ^ Jacobs, H. and Appiah, K. (2004). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave & Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Mass Market Paperback, pp. xiii, 4.

- ^ Bowers, Jerome. Frederick Douglass. Teachinghistory.org. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Julius Eric Thompson; James L. Conyers (2010). The Frederick Douglass encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 124. ISBN 9780313319884. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ "Anna Murray Douglass". BlackPast.org. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Waldo E. Martin (March 1, 1986). The mind of Frederick Douglass. UNC Press Books. p. 15. ISBN 9780807841488. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ a b "Discovering Anna Murray Douglass". South Coast Today. February 17, 2008. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1882). Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. p. 170. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1882). Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. pp. 287–288. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1882). Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. p. 205. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- ^ Chaffin, Tom (February 25, 2011). "Frederick Douglass's Irish Liberty". The New York Times. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Marianne Ruuth (1996). Frederick Douglass p.117-118. Holloway House Publishing, 1996

- ^ Frances E. Ruffin (2008). Frederick Douglass: Rising Up from Slavery. p. 59. ISBN 9781402741180. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- ^ Simon Schama, Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution, New York: HarperCollins, 2006 Pbk, pp. 415–421

- ^ a b c Paul Finkelman (2006). Encyclopedia of African American history, 1619–1895: from the colonial period to the age of Frederick Douglass. Oxford University Press. pp. 104–105. ISBN 9780195167771. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ a b "I am your fellow man, but not your slave,". Retrieved 2012-03-03.

- ^ "Seneca Falls Convention". Virginia Memory. 1920-08-18. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ Stanton, 1997, p. 85.

- ^ USConstitution.net. Text of the "Declaration of Sentiments", and the Resolutions. Retrieved on April 24, 2009.

- ^ a b c McMillen, 2008, pp. 93–94.

- ^ National Park Service. Women's Rights. Report of the Woman's Rights Convention, July 19–20, 1848. Retrieved on April 24, 2009.

- ^ University of Rochester Frederick Douglass Project. [1]. Retrieved on November 26, 2010.

- ^ Slaves in Union-held areas were not covered by this war-measures act.

- ^ "The Fight For Emancipation". Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- ^ Stauffer (2008), Giants, p. 280

- ^ Frederick Douglass; Robert G. O'Meally (November 30, 2003). Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave. Spark Educational Publishing. p. xi. ISBN 9781593080419. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- ^ "Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln by Frederick Douglass". Teachingamericanhistory.org. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- ^ Robin Van Auken, Louis E Hunsinger (2003). Williamsport: Boomtown on the Susquehanna. Arcadia Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 0738524387.

- ^ This is an early version of the four boxes of liberty concept later used by conservatives opposed to gun control

- ^ George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction, Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1984, p. 132

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, pp.12–13, accessed March 10, 2008

- ^ Olasky, Marvin. "History turned right side up". WORLD magazine. February 13, 2010. p. 22.

- ^ Julius Eric Thompson; James L. Conyers (2010). The Frederick Douglass encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 125. ISBN 9780313319884. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Frederick Douglass biography at winningthevote.org. Retrieved October 3, 2006.

- ^ Julius Eric Thompson; James L. Conyers (2010). The Frederick Douglass encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 46. ISBN 9780313319884. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Richard Reid, "The Gloria Rackley-Blackwell story" The Times and Democrat, (February 22, 2011). Retrieved June 3, 2011

- ^ "Past Convention Highlights." Republican Convention 2000. CNN/AllPolitics.com. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ National Convention, Republican Party (U.S. : 1854- ) (1903). Official Proceedings of the Republican National Convention Held at Chicago, June 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 and 25, 1888.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "CNN: Think you know your Democratic convention trivia?". August 26, 2008. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ "Maryland Historical Trust". Douglass Place, Baltimore City. Maryland Historical Trust. 2008-11-21.

- ^ "Prominent Alpha Men". Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ^ "Frederick Douglass Bill is Approved by President: Bill making F Douglass home, Washington, DC, part of natl pk system signed". The New York Times. September 6, 1962.

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ^ Clines, Francis X. (November 3, 2006). "Summoning Frederick Douglass". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Dominus, Susan (May 21, 2010). [A Slow Tribute That Might Try the Subject’s Patience "A Slow Tribute That Might Try the Subject's Patience"]. The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Holt, Dustin (June 12, 2011). "Douglass statue arrives in Easton". The Star Democrat. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ archive.org

- ^ lib.rochester.edu

- ^ "Frederick Douglass and 'Riversmeet': connecting 19th century struggles", Socialist Worker online, December 1, 2007

- ^ Civilization Revolution: Great People "CivFanatics" Retrieved on September 3, 2009

Further reading

- Scholarship

- Gates, Jr., Henry Louis, ed. Frederick Douglass, Autobiography (Library of America, 1994) ISBN 978-0-940450-79-0

- Foner, Philip Sheldon. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass. New York: International Publishers, 1950.

- Houston A. Baker, Jr., Introduction, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Penguin, 1986 edition.

- Huggins, Nathan Irvin, and Oscar Handlin. Slave and Citizen: The Life of Frederick Douglass. Library of American Biography. Boston: Little, Brown, 1980; Longman (1997). ISBN 0-673-39342-9

- Lampe, Gregory P. Frederick Douglass: Freedom's Voice. Rhetoric and Public Affairs Series. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1998. ISBN-X (alk. paper) ISBN (pbk. alk. paper) (on his oratory)

- Levine, Robert S. Martin Delany, Frederick Douglass, and the Politics of Representative Identity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. ISBN (alk. paper). ISBN (pbk.: alk. paper) (cultural history)

- McFeely, William S. Frederick Douglass. New York: Norton, 1991. ISBN 0-393-31376-X

- McMillen, Sally Gregory. Seneca Falls and the origins of the women's rights movement. Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-19-518265-0

- Oakes, James. The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. 2007. ISBN 0-393-06194-9

- Quarles, Benjamin. Frederick Douglass. Washington: Associated Publishers, 1948.

- Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; edited by Theodore Stanton and Harriot Stanton Blatch. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, As Revealed in Her Letters, Diary and Reminiscences, Harper & Brothers, 1922.

- Webber, Thomas, Deep Like Rivers: Education in the Slave Quarter Community 1831–1865. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. (1978).

- Woodson, C.G., The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861: A History of the Education of the Colored People of the United States from the Beginning of Slavery to the Civil War. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, (1915); Indy Publ. (2005) ISBN 1-4219-2670-9

- For young readers

- Miller, William. Frederick Douglass: The Last Day of Slavery. Illus. by Cedric Lucas. Lee & Low Books, 1995. ISBN 1-880000-42-3

- Weidt, Maryann N. Voice of Freedom: a Story about Frederick Douglass. Illus. by Jeni Reeves. Lerner Publications, (2001). ISBN 1-57505-553-8

- Documentary films

- Frederick Douglass and the White Negro [videorecording] / Writer/Director John J Doherty, produced by Camel Productions, Ireland. Irish Film Board/TG4/BCI.; 2008

- Frederick Douglass [videorecording] / produced by Greystone Communications, Inc. for A&E Network ; executive producers, Craig Haffner and Donna E. Lusitana.; 1997

- Frederick Douglass: When the Lion Wrote History [videorecording] / a co-production of ROJA Productions and WETA-TV.

- Frederick Douglass, Abolitionist Editor [videorecording]/a production of Schlessinger Video Productions.

- Race to Freedom [videorecording] : the story of the underground railroad / an Atlantis

External links

Douglass sources online

- The Frederick Douglass Papers Edition : A Critical Edition of Douglass' Complete Works, including speeches, autobiographies, letters, and other writings.

- Works by Frederick Douglass at Internet Archive (scanned books original editions illustrated)

- Works by Frederick Douglass at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Frederick Douglass at Online Books Page

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself. Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845.

- The Heroic Slave. From Autographs for Freedom, Ed. Julia Griffiths. Boston: John P. Jewett and Company. Cleveland, Ohio: Jewett, Proctor, and Worthington. London: Low and Company., 1853.

- My Bondage and My Freedom. Part I. Life as a Slave. Part II. Life as a Freeman. New York: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1855.

- Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: His Early Life as a Slave, His Escape from Bondage, and His Complete History to the Present Time. Hartford, Conn.: Park Publishing Co., 1881.

- Frederick Douglass lecture on Haiti – Given at the World's Fair in Chicago, January 1893.

- Fourth of July Speech

- Letter to Thomas Auld (September 3, 1848)

- The Frederick Douglass Diary (1886-87)

- The Liberator Files, Items concerning Frederick Douglass from Horace Seldon's collection and summary of research of William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator original copies at the Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts.

- What to the Slave is the Fourth of July? July 5, 1852 EDSITEment Launchpad

- Video. In the Words of Frederick Douglass January 27, 2012.

Resource Guides

- Frederick Douglass: Online Resources from the Library of Congress

Biographical information

- Frederick Douglass Project at the University of Rochester.

- Frederick Douglass (American Memory, Library of Congress) Includes timeline.

- Timeline of Frederick Douglass and family

- Timeline of "The Life of Frederick Douglass" – Features key political events

- Read more about Frederick Douglass

- Frederick Douglass NHS – Douglass' Life

- Frederick Douglass NHS – Cedar Hill National Park Service site

- Frederick Douglass Western New York Suffragists

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Frederick Douglass

- Mr. Lincoln's White House: Frederick Douglass

- Frederick Douglass at C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History

Memorials to Frederick Douglass

- Frederick Douglass National Historic Site The Washington, DC home of Frederick Douglass

- Frederick Douglass Gardens at Cedar Hill Frederick Douglass Gardens

- Frederick Douglass Circle in Harlem overlooking Central Park has a statue of Frederick Douglass. North of this point, 8th Avenue is referred to as Frederick Douglass Boulevard

- The Frederick Douglass Prize A national book prize

- Lewis N. Douglass as a Sergeant Major in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

- The short film Fighter for Freedom: The Frederick Douglass Story (1984) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Frederick Douglass

- 1818 births

- 1895 deaths

- 19th-century American newspaper editors

- 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people)

- African American United States vice-presidential candidates

- African American memoirists

- African American publishers (people)

- African American writers

- African Americans' rights activists

- American Methodists

- American abolitionists

- American autobiographers

- American feminists

- American newspaper founders

- American slaves

- American suffragists

- Male feminists

- Burials at Mount Hope Cemetery, Rochester

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- Journalists from Upstate New York

- People from Baltimore, Maryland

- People from Rochester, New York

- People from Talbot County, Maryland

- United States Marshals

- Ambassadors of the United States to Haiti

- Ambassadors of the United States to the Dominican Republic

- United States presidential candidates, 1888

- United States vice-presidential candidates, 1872