Serval

| Serval[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| At Serengeti National Park, Tanzania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | Leptailurus Severtzov, 1858

|

| Species: | L. serval

|

| Binomial name | |

| Leptailurus serval (Schreber, 1776)

| |

| |

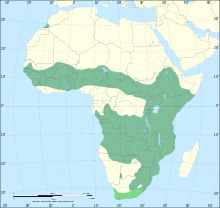

| Serval range. Darker green: extant (resident). Brighter green: extinct. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Caracal serval [2] | |

The serval (/ˈsɜːrvəl/) (Leptailurus serval) known in Afrikaans as Tierboskat, "tiger-forest-cat", is a medium-sized African wild cat. DNA studies have shown that the serval is closely related to the African golden cat and the caracal.[3]

Description

The serval is a medium-sized cat, measuring 59 to 92 cm (23 to 36 in) in head-body length, with a relatively short, 20 to 45 cm (7.9 to 17.7 in) tail, and a shoulder height of about 54 to 66 cm (21 to 26 in).[4] Weight ranges from about 7 to 12 kg (15 to 26 lb) in females, and from 9 to 18 kg (20 to 40 lb) in males.[5]

It is a strong yet slender animal, with long legs and a fairly short tail. Due to its leg length, it is relatively one of the tallest cats. The head is small in relation to the body, and the tall, oval ears are set close together. The pattern of the fur is variable. Usually, the serval is boldly spotted black on tawny, with two or four stripes from the top of the head down the neck and back, transitioning into spots. The "servaline" form has much smaller, freckled spots, and was once thought to be separate species. The backs of the ears are black with a distinctive white bar. In addition, melanistic servals are quite common in some parts of the range, giving a similar appearance to the "black panther" (melanistic leopard).[5]

White servals have never been documented in the wild and only four have been documented in captivity. One was born and died at the age of two weeks in Canada in the early 1990s. The other three, all males, were born at Big Cat Rescue on Easy Street in 1997 (Kongo and Tonga) and 1999 (Pharaoh).[6][7] Kongo also died in 2004 after a severe reaction to hay bedding.[8] Another is owned by a family living in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada.[9]

Servals have the longest legs of any cat, relative to their body size. Most of this increase in length is due to the greatly elongated metatarsal bones in the feet. The toes are also elongated, and unusually mobile, helping the animal to capture partially concealed prey. Another distinctive feature of the serval is the presence of large ears and auditory bullae in the skull, indicating a particularly acute sense of hearing.[5]

Distribution and habitat

The serval is native to Africa, where it is widely distributed south of the Sahara. It was once also found in Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria,[5] but may have been extirpated from Algeria and remains in Tunisia only because of a reintroduction programme.[2]

Its main habitat is the savanna, although melanistic individuals are more usually found in mountainous areas at elevations up to 3,000 metres (9,800 ft). The serval needs watercourses within its territory, so it does not live in semi-deserts or dry steppes. Servals also avoid dense equatorial jungles, although they may be found along forest fringes. They are able to climb and swim, but seldom do so.[5]

Subspecies

Nineteen subspecies were recognized in Mammal Species of the World,[1] but some authorities treat several of these as synonyms (a few have even treated the serval as monotypic).[10]

- Leptailurus serval serval, Cape Province;

- Leptailurus serval beirae, Mozambique;

- Leptailurus serval brachyurus, West Africa, Sahel to Ethiopia;

- Leptailurus serval constantinus, Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia;

- Leptailurus serval faradjius;

- Leptailurus serval ferrarii;

- Leptailurus serval hamiltoni, eastern Transvaal;

- Leptailurus serval hindei, Tanzania;

- Leptailurus serval kempi, Uganda;

- Leptailurus serval kivuensis, Congo;

- Leptailurus serval lipostictus, northern Angola;

- Leptailurus serval lonnbergi, southern Angola;

- Leptailurus serval mababiensis, northern Botswana;

- Leptailurus serval pantastictus;

- Leptailurus serval phillipsi;

- Leptailurus serval pococki;

- Leptailurus serval robertsi, western Transvaal;

- Leptailurus serval tanae, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia;

- Leptailurus serval togoensis, Togo and Benin.

Hunting and diet

The serval is nocturnal, and so hunts mostly at night, unless disturbed by human activity or the presence of larger nocturnal predators. Although the serval is specialized for catching rodents, it is an opportunistic predator whose diet also includes birds, hares, hyraxes, reptiles, insects, fish, and frogs.[11] The serval has been observed taking larger animals, such as deer, gazelle, and springbok, though over 90% of the serval's prey weighs less than 200 g (7 oz).[12] The serval eats very quickly, sometimes too quickly, causing it to gag and regurgitate due to clogging in the throat.[citation needed] Small prey are devoured whole. With larger prey, small bones are consumed, but organs and intestines are avoided along with fur, feathers, beaks, feet or hooves. The serval utilizes an effective plucking technique in which it repeatedly tosses captured birds in the air while simultaneously thrashing its head from side-to-side, removing mouthfuls of feathers, which it discards.[citation needed]

As part of its adaptations for hunting in the savannas, the serval boasts long legs (the longest of all cats, relative to body size) for jumping, which also help it achieve a top speed of 80 kilometres per hour (50 mph),[citation needed] and has large ears with acute hearing. Its long legs and neck allow the serval to see over tall grasses, while its ears are used to detect prey, even those burrowing underground. Servals have been known to dig into burrows in search of underground prey, and to leap 2 to 3 metres (7 to 10 ft) into the air to grab birds in flight.[5] While hunting, the serval may pause for up to 15 minutes at a time to listen with eyes closed. The Serval's pounce is a distinctive and precise vertical 'hop', which may be an adaptation for capturing flushed birds.[13] It is able to leap up to 3.6 metres (12 ft) horizontally from a stationary position, landing precisely on target with sufficient force to stun or kill its prey upon impact.[5] The serval is an efficient killer, catching prey on an average of 50% of attempts, compared to an average of 38% for leopards and 30% for lions.[citation needed]

The serval is extremely intelligent, and demonstrate remarkable problem-solving ability[citation needed], making it notorious for getting into mischief,[citation needed] as well as easily outwitting its prey, and eluding other predators. The serval will often play with its captured prey for several minutes before consuming it. In most situations, the serval will ferociously defend its food against attempted theft by others. Males can be more aggressive than females.

Behavior

Like most cats, the serval is a solitary, nocturnal animal. It is known to travel as much as 3 to 4 kilometres (1.9 to 2.5 mi) each night in search of food. The female defends home ranges of 9.5 to 19.8 square kilometres (3.7 to 7.6 sq mi), depending on local prey availability, while the male defends larger territories of 11.6 to 31.5 square kilometres (4.5 to 12.2 sq mi), and marks its territory by spraying urine onto prominent objects such as bushes, or, less frequently, by scraping fresh urine into the ground with its claws. Threat displays between hostile servals are often highly exaggerated, with the animals flattening their ears and arching their backs, baring their teeth, and nodding their heads vigorously. In direct confrontation, they lash out with their long forelegs and make sharp barking sounds and loud growls.[5]

Like many cats, the serval is able to purr.[14][15] The serval also has a high-pitched chirp, and can hiss, cackle, growl, grunt, and meow.[5]

Reproduction and life history

Oestrus in the serval lasts for up to four days, and is typically timed so the kittens will be born shortly before the peak breeding period of local rodent populations. A serval is able to give birth to multiple litters throughout the year, but commonly does so only if the earlier litters die shortly after birth. Gestation lasts from 66 to 77 days and commonly results in the birth of two kittens, although sometimes as few as one or as many as four have been recorded.[5]

The kittens are born in dense vegetation or sheltered locations such as abandoned aardvark burrows. If such an ideal location is not available, a place beneath a shrub may be sufficient. The kittens weigh around 250 g (8.8 oz) at birth, and are initially blind and helpless, with a coat of greyish woolly hair. They open their eyes at 9 to 13 days of age, and begin to take solid food after around a month. At around six months, they acquire their permanent canine teeth and begin to hunt for themselves; they leave their mother at about 12 months of age. They may reach sexual maturity from 12 to 25 months of age.[5]

Life expectancy is about 10 years in the wild, and up to 20 years in captivity.[16]

Conservation

The serval has dwindled in numbers due to human population taking over its habitat and hunting for its pelts. The serval is sometimes preyed upon by the leopard and other large cats. The serval is listed in CITES Appendix 2, indicating it is "not necessarily now threatened with extinction, but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled."[17] It is still common—locally even expanding—in much of sub-Saharan Africa,[2] but it is extinct in the Cape Province in South Africa. North of the Sahara, it occurs in only Morocco and Algeria, but has now possibly disappeared from the latter country[2] and the subspecies from this region (L. s. constantina) is considered endangered under US-ESA.[18] It formerly occurred naturally in Tunisia, but now only through a reintroduction program based on servals from East Africa.[2]

Heraldry and literature

The serval Template:In it was the symbol of the Tomasi family, princes of Lampedusa, whose best-known member was Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, author of one of the most famous Italian novels of the 20th century, Il Gattopardo.

References

- ^ a b Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 540. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d e f Template:IUCN2008 Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern

- ^ Johnson, W. E.; Eizirik, E; Pecon-Slattery, J; Murphy, WJ; Antunes, A; Teeling, E; O'Brien, SJ (2006). "The Late Miocene Radiation of Modern Felidae: A Genetic Assessment". Science. 311 (5757): 73–77. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146.

- ^ Burnie D and Wilson DE (Eds.), Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. DK Adult (2005), ISBN 0789477645

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sunquist, Mel; Sunquist, Fiona (2002). Wild cats of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 142–151. ISBN 0-226-77999-8.

- ^ Pharaoh. Big Cat Rescue. Retrieved on 2012-07-03.

- ^ Tonga. Big Cat Rescue. Retrieved on 2012-07-03.

- ^ Kongo White Serval - tributes. Sites.google.com. Retrieved on 2012-07-03.

- ^ "Regina family wins fight to keep exotic cat as house pet (video)". CTV News. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ Kingdon, J. (1997). The Kingdon Guide to African Mammals. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-408355-2

- ^ "Serval". African Wildlife Foundation. Retrieved 13 March 2007.

- ^ "The Serval". Cat Survival Trust. Retrieved 13 March 2007.

- ^ Hunter, Luke, Hinde, Gerald (2005). Cats of Africa. New Holland Publishers. pp. 61–62. ISBN 177007063X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robert Eklund's Ingressive Speech website. Ingressivespeech.info. Retrieved on 2012-07-03.

- ^ Robert Eklund's Wildlife page. Roberteklund.info. Retrieved on 2012-07-03.

- ^ Tonkin, B.A. (1972). "Notes on longevity in three species of felids". International Zoo Yearbook. 12: 181–182. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1972.tb02319.x.

- ^ CITES Appendices. cites.org

- ^ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2011). Leptailurus serval constantina. Endangered Species Act.

External links

- world conservation union site - detailed information

- big cats online - short write-up

- servals.org - servals in the wild and as pets

- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Use dmy dates from August 2011

- IUCN Red List endangered species

- Felines

- Animals described in 1776

- Mammals of Algeria

- Mammals of Angola

- Mammals of Botswana

- Mammals of Burkina Faso

- Mammals of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Fauna of East Africa

- Mammals of Kenya

- Mammals of Morocco

- Mammals of Namibia

- Fauna of the Sahara

- Mammals of South Africa

- Mammals of Tanzania

- Fauna of West Africa

- Mammals of Zambia

- Mammals of Africa

- Pet mammals

- Monotypic mammal genera

- Mammals of Uganda