Coral reef

| Marine habitats |

|---|

|

| Coastal habitats |

| Ocean surface |

| Open ocean |

| Sea floor |

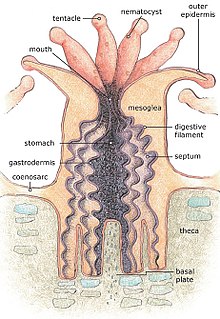

Coral reefs are underwater structures made from calcium carbonate secreted by corals. Coral reefs are colonies of tiny animals found in marine waters that contain few nutrients. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, which in turn consist of polyps that cluster in groups. The polyps belong to a group of animals known as Cnidaria, which also includes sea anemones and jellyfish. Unlike sea anemones, coral polyps secrete hard carbonate exoskeletons which support and protect their bodies. Reefs grow best in warm, shallow, clear, sunny and agitated waters.

Often called "rainforests of the sea", coral reefs form some of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth. They occupy less than 0.1% of the world's ocean surface, about half the area of France, yet they provide a home for 25% of all marine species,[1][2][3] including fish, mollusks, worms, crustaceans, echinoderms, sponges, tunicates and other cnidarians.[4] Paradoxically, coral reefs flourish even though they are surrounded by ocean waters that provide few nutrients. They are most commonly found at shallow depths in tropical waters, but deep water and cold water corals also exist on smaller scales in other areas.

Coral reefs deliver ecosystem services to tourism, fisheries and shoreline protection. The annual global economic value of coral reefs was estimated at US$ 375 billion in 2002. However, coral reefs are fragile ecosystems, partly because they are very sensitive to water temperature. They are under threat from climate change, oceanic acidification, blast fishing, cyanide fishing for aquarium fish, overuse of reef resources, and harmful land-use practices, including urban and agricultural runoff and water pollution, which can harm reefs by encouraging excess algal growth.[5][6][7]

Formation and history

Most coral reefs were formed after the last glacial period when melting ice caused the sea level to rise and flood the continental shelves. This means that most coral reefs are less than 10,000 years old. As communities established themselves on the shelves, the reefs grew upwards, pacing rising sea levels. Reefs that rose too slowly could become drowned reefs, covered by so much water that there was insufficient light.[8] Coral reefs are found in the deep sea away from continental shelves, around oceanic islands and as atolls. The vast majority of these islands are volcanic in origin. The few exceptions have tectonic origins where plate movements have lifted the deep ocean floor on the surface.

In 1842 in his first monograph, The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs[9] Charles Darwin set out his theory of the formation of atoll reefs, an idea he conceived during the voyage of the Beagle. He theorized uplift and subsidence of the Earth's crust under the oceans formed the atolls.[10] Darwin’s theory sets out a sequence of three stages in atoll formation. It starts with a fringing reef forming around an extinct volcanic island as the island and ocean floor subsides. As the subsidence continues, the fringing reef becomes a barrier reef, and ultimately an atoll reef.

-

Darwin’s theory starts with a volcanic island which becomes extinct

-

As the island and ocean floor subside, coral growth builds a fringing reef, often including a shallow lagoon between the land and the main reef.

-

As the subsidence continues, the fringing reef becomes a larger barrier reef further from the shore with a bigger and deeper lagoon inside.

-

Ultimately, the island sinks below the sea, and the barrier reef becomes an atoll enclosing an open lagoon.

Darwin predicted that underneath each lagoon would be a bed rock base, the remains of the original volcano. Subsequent drilling proved this correct. Darwin's theory followed from his understanding that coral polyps thrive in the clean seas of the tropics where the water is agitated, but can only live within a limited depth range, starting just below low tide. Where the level of the underlying earth allows, the corals grow around the coast to form what he called fringing reefs, and can eventually grow out from the shore to become a barrier reef.

Where the bottom is rising, fringing reefs can grow around the coast, but coral raised above sea level dies and becomes white limestone. If the land subsides slowly, the fringing reefs keep pace by growing upwards on a base of older, dead coral, forming a barrier reef enclosing a lagoon between the reef and the land. A barrier reef can encircle an island, and once the island sinks below sea level a roughly circular atoll of growing coral continues to keep up with the sea level, forming a central lagoon. Barrier reefs and atolls do not usually form complete circles, but are broken in places by storms. Like sea level rise, a rapidly subsiding bottom subside can overwhelm coral growth, killing the animals and the reef.[10][12]

The two main variables determining the geomorphology, or shape, of coral reefs are the nature of the underlying substrate on which they rest, and the history of the change in sea level relative to that substrate.

The approximately 20,000 year old Great Barrier Reef offers an example of how coral reefs formed on continental shelves. Sea level was then 120 m (390 ft) lower than in the 21st century.[13][14] As sea level rose, the water and the corals encroached on what had been hills of the Australian coastal plain. By 13,000 years ago, sea level had risen to 60 m (200 ft) lower than at present, and many hills of the coastal plains had become continental islands. As the sea level rise continued, water topped most of the continental islands. The corals could then overgrow the hills, forming the present cays and reefs. Sea level on the Great Barrier Reef has not changed significantly in the last 6,000 years,[14] and the age of the modern living reef structure is estimated to be between 6,000 and 8,000 years.[15] Although the Great Barrier Reef formed along a continental shelf, and not around a volcanic island, Darwin's principles apply. Development stopped at the barrier reef stage, since Australia is not about to submerge. It formed the world's largest barrier reef, 300–1,000 m (980–3,300 ft) from shore, stretching for 2,000 km (1,200 mi).[16]

Healthy tropical coral reefs grow horizontally from 1 to 3 cm (0.39 to 1.2 in) per year, and grow vertically anywhere from 1 to 25 cm (0.39 to 9.8 in) per year; however, they grow only at depths shallower than 150 m (490 ft) because of their need for sunlight, and cannot grow above sea level.[17]

Materials

As the name implies, the bulk of coral reefs is made up of coral skeletons from mostly intact coral colonies. However, shell fragments and the remains of calcareous algae such as the green-segmented genus Halimeda can add to the reef's ability to withstand damage from storms and other threats. Such mixtures are visible in structures such as Eniwetok Atoll.[18]

Types

The three principal reef types are:

- Fringing reef – this type is directly attached to a shore, or borders it with an intervening shallow channel or lagoon.

- Barrier reef – a reef separated from a mainland or island shore by a deep channel or lagoon

- Atoll reef – this more or less circular or continuous barrier reef extends all the way around a lagoon without a central island.

Other reef types or variants are:

- Patch reef – this type is an isolated, comparatively small reef outcrop, usually within a lagoon or embayment, often circular and surrounded by sand or seagrass. Patch reefs are common.

- Apron reef – a short reef resembling a fringing reef, but more sloped; extending out and downward from a point or peninsular shore

- Bank reef – a linear or semicircular shaped-outline, larger than a patch reef

- Ribbon reef – a long, narrow, possibly winding reef, usually associated with an atoll lagoon

- Table reef – an isolated reef, approaching an atoll type, but without a lagoon

- Habili – this is a reef in the Red Sea that does not reach the surface near enough to cause visible surf, although it may be a hazard to ships (from the Arabic for "unborn").

- Microatoll – certain species of corals form communities called microatolls. The vertical growth of microatolls is limited by average tidal height. By analyzing growth morphologies, microatolls offer a low-resolution record of patterns of sea level change. Fossilized microatolls can also be dated using radioactive carbon dating. Such methods have been used to reconstruct Holocene sea levels.[19]

- Cays – are small, low-elevation, sandy islands formed on the surface of coral reefs. Material eroded from the reef piles up on parts of the reef or lagoon, forming an area above sea level. Plants can stabilize cays enough to become habitable by humans. Cays occur in tropical environments throughout the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans (including the Caribbean and on the Great Barrier Reef and Belize Barrier Reef), where they provide habitable and agricultural land for hundreds of thousands of people.

- When a coral reef cannot keep up with the sinking of a volcanic island, a seamount or guyot is formed. The tops of seamounts and guyots are below the surface. Seamounts are rounded at the top and guyots are flat. The flat top of the guyot, also called a tablemount, is due to erosion by waves, winds, and atmospheric processes.

Zones

Coral reef ecosystems contain distinct zones that represent different kinds of habitats. Usually, three major zones are recognized: the fore reef, reef crest, and the back reef (frequently referred to as the reef lagoon).

All three zones are physically and ecologically interconnected. Reef life and oceanic processes create opportunities for exchange of seawater, sediments, nutrients, and marine life among one another.

Thus, they are integrated components of the coral reef ecosystem, each playing a role in the support of the reefs' abundant and diverse fish assemblages.

Most coral reefs exist in shallow waters less than 50 m deep. Some inhabit tropical continental shelves where cool, nutrient rich upwelling does not occur, such as Great Barrier Reef. Others are found in the deep ocean surrounding islands or as atolls, such as in the Maldives. The reefs surrounding islands form when islands subside into the ocean, and atolls form when an island subsides below the surface of the sea.

Alternatively, Moyle and Cech distinguish six zones, though most reefs possess only some of the zones.[20]

- The reef surface is the shallowest part of the reef. It is subject to the surge and the rise and fall of tides. When waves pass over shallow areas, they shoal, as shown in the diagram at the right. This means the water is often agitated. These are the precise condition under which corals flourish. Shallowness means there is plenty of light for photosynthesis by the symbiotic zooxanthellae, and agitated water promotes the ability of coral to feed on plankton. However, other organisms must be able to withstand the robust conditions to flourish in this zone.

- The off-reef floor is the shallow sea floor surrounding a reef. This zone occurs by reefs on continental shelves. Reefs around tropical islands and atolls drop abruptly to great depths, and do not have a floor. Usually sandy, the floor often supports seagrass meadows which are important foraging areas for reef fish.

- The reef drop-off is, for its first 50 m, habitat for many reef fish who find shelter on the cliff face and plankton in the water nearby. The drop-off zone applies mainly to the reefs surrounding oceanic islands and atolls.

- The reef face is the zone above the reef floor or the reef drop-off. "It is usually the richest habitat. Its complex growths of coral and calcareous algae provide cracks and crevices for protection, and the abundant invertebrates and epiphytic algae provide an ample source of food."[20]

- The reef flat is the sandy-bottomed flat can be behind the main reef, containing chunks of coral. "The reef flat may be a protective area bordering a lagoon, or it may be a flat, rocky area between the reef and the shore. In the former case, the number of fish species living in the area often is the highest of any reef zone."[20]

- The reef lagoon – "many coral reefs completely enclose an area, thereby creating a quiet-water lagoon that usually contains small patches of reef."[20]

However, the "topography of coral reefs is constantly changing. Each reef is made up of irregular patches of algae, sessile invertebrates, and bare rock and sand. The size, shape and relative abundance of these patches changes from year to year in response to the various factors that favor one type of patch over another. Growing coral, for example, produces constant change in the fine structure of reefs. On a larger scale, tropical storms may knock out large sections of reef and cause boulders on sandy areas to move."[21]

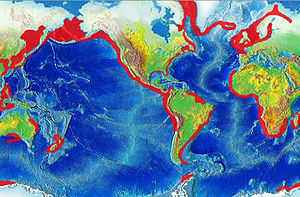

Locations

Coral reefs are estimated to cover 284,300 km2 (109,800 sq mi),[22] just under 0.1% of the oceans' surface area. The Indo-Pacific region (including the Red Sea, Indian Ocean, Southeast Asia and the Pacific) account for 91.9% of this total. Southeast Asia accounts for 32.3% of that figure, while the Pacific including Australia accounts for 40.8%. Atlantic and Caribbean coral reefs account for 7.6%.[2]

Although corals exist both in temperate and tropical waters, shallow-water reefs form only in a zone extending from 30° N to 30° S of the equator. Tropical corals do not grow at depths of over 50 meters (160 ft). The optimum temperature for most coral reefs is 26–27 °C (79–81 °F), and few reefs exist in waters below 18 °C (64 °F).[23] However, reefs in the Persian Gulf have adapted to temperatures of 13 °C (55 °F) in winter and 38 °C (100 °F) in summer.[24] There are 37 species of scleractinian corals identified in such harsh environment around Larak Island.[25]

Deep-water coral can exist at greater depths and colder temperatures at much higher latitudes, as far north as Norway.[26] Although deep water corals can form reefs, very little is known about them.

Coral reefs are rare along the American and African west coasts. This is due primarily to upwelling and strong cold coastal currents that reduce water temperatures in these areas (respectively the Peru, Benguela and Canary streams).[27] Corals are seldom found along the coastline of South Asia from the eastern tip of India (Madras) to the Bangladesh and Myanmar borders.[2] They are also rare along the coast around northeastern South America and Bangladesh due to the freshwater release from the Amazon and Ganges Rivers, respectively.

- The Great Barrier Reef—largest, comprising over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over 2,600 kilometers (1,600 mi) off Queensland, Australia

- The Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System—second largest, stretching 1,000 kilometers (620 mi) from Isla Contoy at the tip of the Yucatán Peninsula down to the Bay Islands of Honduras

- The New Caledonia Barrier Reef—second longest double barrier reef, covering 1,500 kilometers (930 mi)

- The Andros, Bahamas Barrier Reef—third largest, following the east coast of Andros Island, Bahamas, between Andros and Nassau

- The Red Sea—includes 6000-year-old fringing reefs located around a 2,000 km (1,240 mi) coastline

- The Florida Reef Tract—largest continental US reef, extends from Soldier Key, located in Biscayne Bay, to the Dry Tortugas in the Gulf of Mexico[28]

- Pulley Ridge—deepest photosynthetic coral reef, Florida

- Numerous reefs scattered over the Maldives

- The Philippines coral reef area, the second largest in Southeast Asia, is estimated at 26,000 square kilometers and holds an extraordinary diversity of species. Scientists have identified 915 reef fish species and more than 400 scleractinian coral species, 12 of which are endemic.

- The Raja Ampat Islands in Indonesia's West Papua province offer the highest known marine diversity.[29]

Biology

Live coral are small animals embedded in calcium carbonate shells. It is a mistake to think of coral as plants or rocks. Coral heads consist of accumulations of individual animals called polyps, arranged in diverse shapes.[30] Polyps are usually tiny, but they can range in size from a pinhead to 12 inches (30 cm) across.

Reef-building or hermatypic corals live only in the photic zone (above 50 m), the depth to which sufficient sunlight penetrates the water, allowing photosynthesis to occur. Coral polyps do not photosynthesize, but have a symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae; these organisms live within the tissues of polyps and provide organic nutrients that nourish the polyp. Because of this relationship, coral reefs grow much faster in clear water, which admits more sunlight. Without their symbionts, coral growth would be too slow to form significant reef structures. Corals get up to 90% of their nutrients from their symbionts.[31]

Reefs grow as polyps and other organisms deposit calcium carbonate,[32][33] the basis of coral, as a skeletal structure beneath and around themselves, pushing the coral head's top upwards and outwards.[34] Waves, grazing fish (such as parrotfish), sea urchins, sponges, and other forces and organisms act as bioeroders, breaking down coral skeletons into fragments that settle into spaces in the reef structure or form sandy bottoms in associated reef lagoons. Many other organisms living in the reef community contribute skeletal calcium carbonate in the same manner.[35] Coralline algae are important contributors to reef structure in those parts of the reef subjected to the greatest forces by waves (such as the reef front facing the open ocean). These algae strengthen the reef structure by depositing limestone in sheets over the reef surface.

The colonies of the one thousand coral species assume a characteristic shape such as wrinkled brains, cabbages, table tops, antlers, wire strands and pillars.[citation needed]

Corals reproduce both sexually and asexually. An individual polyp uses both reproductive modes within its lifetime. Corals reproduce sexually by either internal or external fertilization. The reproductive cells are found on the mesentery membranes that radiate inward from the layer of tissue that lines the stomach cavity. Some mature adult corals are hermaphroditic; others are exclusively male or female. A few species change sex as they grow.

Internally fertilized eggs develop in the polyp for a period ranging from days to weeks. Subsequent development produces a tiny larva, known as a planula. Externally fertilized eggs develop during synchronized spawning. Polyps release eggs and sperm into the water en masse, simultaneously. Eggs disperse over a large area. The timing of spawning depends on time of year, water temperature, and tidal and lunar cycles. Spawning is most successful when there is little variation between high and low tide. The less water movement, the better the chance for fertilization. Ideal timing occurs in the spring. Release of eggs or planula usually occurs at night, and is sometimes in phase with the lunar cycle (three to six days after a full moon). The period from release to settlement lasts only a few days, but some planulae can survive afloat for several weeks. They are vulnerable to predation and environmental conditions. The lucky few planulae which successfully attach to substrate next confront competition for food and space.[citation needed]

-

Spiral wire coral

Darwin's paradox

Darwin's paradox Coral... seems to proliferate when ocean waters are warm, poor, clear and agitated, a fact which Darwin had already noted when he passed through Tahiti in 1842.

This constitutes a fundamental paradox, shown quantitatively by the apparent impossibility of balancing input and output of the nutritive elements which control the coral polyp metabolism.

Recent oceanographic research has brought to light the reality of this paradox by confirming that the oligotrophy of the ocean euphotic zone persists right up to the swell-battered reef crest. When you approach the reef edges and atolls from the quasidesert of the open sea, the near absence of living matter suddenly becomes a plethora of life, without transition. So why is there something rather than nothing, and more precisely, where do the necessary nutrients for the functioning of this extraordinary coral reef machine come from ? — Francis Rougerie[36]

During his voyage on the Beagle, Darwin described tropical coral reefs as oases in the desert of the ocean. He reflected on the paradox that tropical coral reefs, which are among the richest and most diverse ecosystems on earth, flourish surrounded by tropical ocean waters that provide hardly any nutrients.[citation needed]

Coral reefs cover less than 0.1% of the surface of the world’s ocean, yet they support over one-quarter of all marine species. This diversity results in complex food webs, with large predator fish eating smaller forage fish that eat yet smaller zooplankton and so on. However, all food webs eventually depend on plants, which are the primary producers. Coral reefs' primary productivity is very high, typically producing 5–10 g·cm−2·day−1 biomass.[37]

One reason for the unusual clarity of tropical waters is they are deficient in nutrients and drifting plankton. Further, the sun shines year round in the tropics, warming the surface layer, making it less dense than subsurface layers. The warmer water is separated from deeper, cooler water by a stable thermocline, where the temperature makes a rapid change. This keeps the warm surface waters floating above the cooler deeper waters. In most parts of the ocean, there is little exchange between these layers. Organisms that die in aquatic environments generally sink to the bottom, where they decompose, which releases nutrients in the form of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K). These nutrients are necessary for plant growth, but in the tropics, they do not directly return to the surface.[12]

Plants form the base of the food chain, and need sunlight and nutrients to grow. In the ocean, these plants are mainly microscopic phytoplankton which drift in the water column. They need sunlight for photosynthesis, which powers carbon fixation, so they are found only relatively near the surface. But they also need nutrients. Phytoplankton rapidly use nutrients in the surface waters, and in the tropics, these nutrients are not usually replaced because of the thermocline.[12]

Around coral reefs, lagoons fill in with material eroded from the reef and the island. They become havens for marine life, providing protection from waves and storms.

Most importantly, reefs recycle nutrients, which happens much less in the open ocean. In coral reefs and lagoons, producers include phytoplankton, as well as seaweed and coralline algae, especially small types called turf algae, which pass nutrients to corals.[38] The phytoplankton are eaten by fish and crustaceans, who also pass nutrients along the food web. Recycling ensures fewer nutrients are needed overall to support the community.

Coral reefs support many symbiotic relationships. In particular, zooxanthellae provide energy to coral in the form of glucose, glycerol, and amino acids.[39] Zooxanthellae can provide up to 90% of a coral’s energy requirements.[40] In return, as an example of mutualism, the corals shelter the zooxanthellae, averaging one million for every cubic centimeter of coral, and provide a constant supply of the carbon dioxide they need for photosynthesis.

Corals also absorb nutrients, including inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus, directly from water. Many corals extend their tentacles at night to catch zooplankton that brush them when the water is agitated. Zooplankton provide the polyp with nitrogen, and the polyp shares some of the nitrogen with the zooxanthellae, which also require this element.[38] The varying pigments in different species of zooxanthellae give them an overall brown or golden-brown appearance, and give brown corals their colors. Other pigments such as reds, blues, greens, etc. come from colored proteins made by the coral animals. Coral which loses a large fraction of its zooxanthellae becomes white (or sometimes pastel shades in corals that are richly pigmented with their own colorful proteins) and is said to be bleached, a condition which, unless corrected, can kill the coral.

Sponges are another key to explaining Darwin’s paradox. They live in crevices in the coral reefs. They are efficient filter feeders, and in the Red Sea they consume about 60% of the phytoplankton that drifts by. The sponges eventually excrete nutrients in a form the corals can use.[41]

The roughness of coral surfaces is the key to coral survival in agitated waters. Normally, a boundary layer of still water surrounds a submerged object, which acts as a barrier. Waves breaking on the extremely rough edges of corals disrupt the boundary layer, allowing the corals access to passing nutrients. Turbulent water thereby promotes reef growth and branching. Without the nutritional gains brought by rough coral surfaces, even the most effective recycling would leave corals wanting in nutrients.[42]

Studies have shown that deep nutrient-rich water entering coral reefs through isolated events may have significant effects on temperature and nutrient systems.[43][44] This water movement disrupts the relatively stable thermocline that usually exists between warm shallow water to deeper colder water. Leichter et al. (2006)[45] found that temperature regimes on coral reefs in the Bahamas and Florida were highly variable with temporal scales of minutes to seasons and spatial scales across depths.

Water can be moved through coral reefs in various ways, including current rings, surface waves, internal waves and tidal changes.[43][46][47][48] Movement is generally created by tides and wind. As tides interact with varying bathymetry and wind mixes with surface water, internal waves are created. An internal wave is a gravity wave that moves along density stratification within the ocean. When a water parcel encounters a different density it will oscillate and create internal waves.[49] While internal waves generally have a lower frequency than surface waves, they often form as a single wave that breaks into multiple waves as it hits a slope and moves upward.[50] This vertical break up of internal waves causes significant diapycnal mixing and turbulence.[51][52] Internal waves can act as nutrient pumps, bringing plankton and cool nutrient-rich water up to the surface.[43][48][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61]

The irregular structure characteristic of coral reef bathymetry may enhance mixing and produce pockets of cooler water and variable nutrient content.[62] Arrival of cool, nutrient-rich water from depths due to internal waves and tidal bores has been linked to growth rates of suspension feeders and benthic algae[48][61][63] as well as plankton and larval organisms.[48][64] Leichter et al.[61] proposed that Codium isthmocladum react to deep water nutrient sources due to their tissues having different concentrations of nutrients dependent upon depth. Wolanski and Hamner[55] noted aggregations of eggs, larval organisms and plankton on reefs in response to deep water intrusions. Similarly, as internal waves and bores move vertically, surface-dwelling larval organisms are carried toward the shore.[64] This has significant biological importance to cascading effects of food chains in coral reef ecosystems and may provide yet another key to unlocking "Darwin's Paradox".

Cyanobacteria provide soluble nitrates for the reef via nitrogen fixation.[65]

Coral reefs also often depend on surrounding habitats, such as seagrass meadows and mangrove forests, for nutrients. Seagrass and mangroves supply dead plants and animals which are rich in nitrogen and also serve to feed fish and animals from the reef by supplying wood and vegetation. Reefs, in turn, protect mangroves and seagrass from waves and produce sediment in which the mangroves and seagrass can root.[24]

Biodiversity

Coral reefs form some of the world's most productive ecosystems, providing complex and varied marine habitats that support a wide range of other organisms.[66] Fringing reefs just below low tide level have a mutually beneficial relationship with mangrove forests at high tide level and sea grass meadows in between: the reefs protect the mangroves and seagrass from strong currents and waves that would damage them or erode the sediments in which they are rooted, while the mangroves and sea grass protect the coral from large influxes of silt, fresh water and pollutants. This level of variety in the environment benefits many coral reef animals, which, for example, may feed in the sea grass and use the reefs for protection or breeding.[67]

Reefs are home to a large variety of animals, including fish, seabirds, sponges, cnidarians (which includes some types of corals and jellyfish), worms, crustaceans (including shrimp, cleaner shrimp, spiny lobsters and crabs), mollusks (including cephalopods), echinoderms (including starfish, sea urchins and sea cucumbers), sea squirts, sea turtles and sea snakes. Aside from humans, mammals are rare on coral reefs, with visiting cetaceans such as dolphins being the main exception. A few of these varied species feed directly on corals, while others graze on algae on the reef.[2][38] Reef biomass is positively related to species diversity.[68]

The same hideouts in a reef may be regularly inhabited by different species at different times of day. Nighttime predators such as cardinalfish and squirrelfish hide during the day, while damselfish, surgeonfish, triggerfish, wrasses and parrotfish hide from eels and sharks.[18]: 49

Algae

Reefs are chronically at risk of algal encroachment. Overfishing and excess nutrient supply from onshore can enable algae to outcompete and kill the coral.[69][70] In surveys done around largely uninhabited US Pacific islands, algae inhabit a large percentage of surveyed coral locations.[71] The algal population consists of turf algae, coralline algae, and macroalgae.

Sponges

Sponges are essential for the functioning of the coral reef's ecosystem. Algae and corals in coral reefs produce organic material. This is filtered through sponges which convert this organic material into small particles which in turn are absorbed by algae and corals.[72]

Fish

Over 4,000 species of fish inhabit coral reefs.[2] The reasons for this diversity remain controversial. Hypotheses include the "lottery", in which the first (lucky winner) recruit to a territory is typically able to defend it against latecomers, "competition", in which adults compete for territory, and less-competitive species must be able to survive in poorer habitat, and "predation", in which population size is a function of postsettlement piscivore mortality.[73] Healthy reefs can produce up to 35 tons of fish per square kilometer each year, but damaged reefs produce much less.[74]

Invertebrates

Sea urchins, Dotidae and sea slugs eat seaweed. Some species of sea urchins, such as Diadema antillarum, can play a pivotal part in preventing algae from overrunning reefs.[75] Nudibranchia and sea anemones eat sponges.

A number of invertebrates, collectively called cryptofauna, inhabit the coral skeletal substrate itself, either boring into the skeletons (through the process of bioerosion) or living in pre-existing voids and crevices. Those animals boring into the rock include sponges, bivalve mollusks, and sipunculans. Those settling on the reef include many other species, particularly crustaceans and polychaete worms.[27]

Seabirds

Coral reef systems provide important habitats for seabird species, some endangered. For example, Midway Atoll in Hawaii supports nearly three million seabirds, including two-thirds (1.5 million) of the global population of Laysan albatross, and one-third of the global population of black-footed albatross.[76] Each seabird species has specific sites on the atoll where they nest. Altogether, 17 species of seabirds live on Midway. The short-tailed albatross is the rarest, with fewer than 2,200 surviving after excessive feather hunting in the late19th century.[77]

Other

Sea snakes feed exclusively on fish and their eggs. Tropical birds, such as herons, gannets, pelicans and boobies, feed on reef fish. Some land-based reptiles intermittently associate with reefs, such as monitor lizards, the marine crocodile and semiaquatic snakes, such as Laticauda colubrina. Sea turtles eat sponges.[citation needed]

-

Soft coral, cup coral, sponges and ascidians

-

The shell of Latiaxis wormaldi, a coral snail

Economic value

Coral reefs deliver ecosystem services to tourism, fisheries and coastline protection. The global economic value of coral reefs has been estimated at as much as US$ 375 billion per year.[78] Coral reefs protect shorelines by absorbing wave energy, and many small islands would not exist without their reefs to protect them. According to the environmental group World Wide Fund for Nature, the economic cost over a 25-year period of destroying one kilometer of coral reef is somewhere between $137,000 and $1,200,000.[79] About six million tons of fish are taken each year from coral reefs. Well-managed coral reefs have an annual yield of 15 tons of seafood on average per square kilometer. Southeast Asia's coral reef fisheries alone yield about $ 2.4 billion annually from seafood.[79]

To improve the management of coastal coral reefs, another environmental group, the World Resources Institute (WRI) developed and published tools for calculating the value of coral reef-related tourism, shoreline protection and fisheries, partnering with five Caribbean countries. As of April 2011, published working papers covered St. Lucia, Tobago, Belize, and the Dominican Republic, with a paper for Jamaica in preparation. The WRI was also "making sure that the study results support improved coastal policies and management planning".[80] The Belize study estimated the value of reef and mangrove services at $ 395–559 million annually.[81]

Threats

Coral reefs are dying around the world.[82] In particular, coral mining, agricultural and urban runoff, pollution (organic and inorganic), overfishing, blast fishing, disease, and the digging of canals and access into islands and bays are localized threats to coral ecosystems. Broader threats are sea temperature rise, sea level rise and pH changes from ocean acidification, all associated with greenhouse gas emissions. A study released in April 2013 has shown that air pollution can also stunt the growth of coral reefs; researchers from Australia, Panama and the UK used coral records (between 1880 and 2000) from the western Caribbean to show the threat of factors such as coal-burning coal and volcanic eruptions.[83]

In 2011, researchers suggested that "extant marine invertebrates face the same synergistic effects of multiple stressors" that occurred during the end-Permian extinction, and that genera "with poorly buffered respiratory physiology and calcareous shells", such as corals, were particularly vulnerable.[84][85][86]

In El Nino-year 2010, preliminary reports show global coral bleaching reached its worst level since another El Nino year, 1998, when 16% of the world's reefs died as a result of increased water temperature. In Indonesia's Aceh province, surveys showed some 80% of bleached corals died. Scientists do not yet understand the long-term impacts of coral bleaching, but they do know that bleaching leaves corals vulnerable to disease, stunts their growth, and affects their reproduction, while severe bleaching kills them.[87] In July, Malaysia closed several dive sites where virtually all the corals were damaged by bleaching.[88][89]

To find answers for these problems, researchers study the various factors that impact reefs. The list includes the ocean's role as a carbon dioxide sink, atmospheric changes, ultraviolet light, ocean acidification, viruses, impacts of dust storms carrying agents to far-flung reefs, pollutants, algal blooms and others. Reefs are threatened well beyond coastal areas.[citation needed]

General estimates show approximately 10% of the world's coral reefs are dead.[90][91][92] About 60% of the world's reefs are at risk due to destructive, human-related activities. The threat to the health of reefs is particularly strong in Southeast Asia, where 80% of reefs are endangered.[citation needed] By the 2030s, 90% of reefs are expected to be at risk from both human activities and climate change; by 2050, all coral reefs will be in danger.[93]

Current research is showing that ecotourism in the Great Barrier Reef is contributing to coral disease.[94]

Protection

Marine protected areas (MPAs) have become increasingly prominent for reef management. MPAs promote responsible fishery management and habitat protection. Much like national parks and wildlife refuges, and to varying degrees, MPAs restrict potentially damaging activities. MPAs encompass both social and biological objectives, including reef restoration, aesthetics, biodiversity, and economic benefits. Conflicts surrounding MPAs involve lack of participation, clashing views, effectiveness, and funding.[citation needed] In some situations, as in the Phoenix Islands Protected Area, MPAs can also provide revenue, potentially equal to the income they would have generated without controls, as Kiribati did for its Phoenix Islands.[95]

To help combat ocean acidification, some laws are in place to reduce greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide. The Clean Water Act puts pressure on state government agencies to monitor and limit runoff of pollutants that can cause ocean acidification. Stormwater surge preventions are also in place, as well as coastal buffers between agricultural land and the coastline. This act also ensures that delicate watershed ecosystems are intact, such as wetlands. The Clean Water Act is funded by the federal government, and is monitored by various watershed groups. Many land use laws aim to reduce CO2 emissions by limiting deforestation. Deforestation causes erosion, which releases a large amount of carbon stored in the soil, which then flows into the ocean, contributing to ocean acidification. Incentives are used to reduce miles traveled by vehicles, which reduces the carbon emissions into the atmosphere, thereby reducing the amount of dissolved CO2 in the ocean. State and federal governments also control coastal erosion, which releases stored carbon in the soil into the ocean, increasing ocean acidification.[96]

Biosphere reserve, marine park, national monument and world heritage status can protect reefs. For example, Belize's barrier reef, Chagos archipelago, Sian Ka'an, the Galapagos islands, Great Barrier Reef, Henderson Island, Palau and Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument are world heritage sites.[citation needed]

In Australia, the Great Barrier Reef is protected by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, and is the subject of much legislation, including a biodiversity action plan.[citation needed]. They have compiled a Coral Reef Resilience Action Plan. This detailed action plan consists of numerous adaptive management strategies, including reducing our carbon footprint, which would ultimately reduce the amount of ocean acidification in the oceans surrounding the Great Barrier Reef. An extensive public awareness plan is also in place to provide education on the “rainforests of the sea” and how people can reduce carbon emissions, thereby reducing ocean acidification.[97]

Inhabitants of Ahus Island, Manus Province, Papua New Guinea, have followed a generations-old practice of restricting fishing in six areas of their reef lagoon. Their cultural traditions allow line fishing, but no net or spear fishing. The result is both the biomass and individual fish sizes are significantly larger than in places where fishing is unrestricted.[98][99]

Restoration

Coral aquaculture, also known as coral farming or coral gardening, is showing promise as a potentially effective tool for restoring coral reefs, which have been declining around the world.[100][101][102] The process bypasses the early growth stages of corals when they are most at risk of dying. Coral seeds are grown in nurseries, then replanted on the reef.[103] Coral is farmed by coral farmers who live locally to the reefs and farm for reef conservation or for income.

Efforts to expand the size and number of coral reefs generally involve supplying substrate to allow more corals to find a home. Substrate materials include discarded vehicle tires, scuttled ships, subway cars, and formed concrete, such as reef balls. Reefs also grow unaided on marine structures such as oil rigs.[citation needed] In large restoration projects, propagated hermatypic coral on substrate can be secured with metal pins, superglue or milliput.[104] Needle and thread can also attach A-hermatype coral to substrate.[105]

Low-voltage electrical currents applied through seawater crystallize dissolved minerals onto steel structures. The resultant white carbonate (aragonite) is the same mineral that makes up natural coral reefs. Corals rapidly colonize and grow at accelerated rates on these coated structures. The electrical currents also accelerate formation and growth of both chemical limestone rock and the skeletons of corals and other shell-bearing organisms. The vicinity of the anode and cathode provides a high-pH environment which inhibits the growth of competitive filamentous and fleshy algae. The increased growth rates fully depend on the accretion activity.[106]

During accretion, the settled corals display an increased growth rate, size and density, but after the process is complete, growth rate and density return to levels comparable to natural growth, and are about the same size or slightly smaller.[106]

One case study with coral reef restoration was conducted on the island of Oahu in Hawaii. The University of Hawaii has come up with a Coral Reef Assessment and Monitoring Program to help relocate and restore coral reefs in Hawaii. A boat channel on the island of Oahu to the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology was overcrowded with coral reefs. Also, many areas of coral reef patches in the channel had been damaged from past dredging in the channel. Dredging covers the existing corals with sand, and their larvae cannot build and thrive on sand; they can only build on to existing reefs. Because of this, the University of Hawaii decided to relocate some of the coral reef to a different transplant site. They transplanted them with the help of the United States Army Divers, to a relocation site relatively close to the channel. They observed very little, if any, damage occurred to any of the colonies while they were being transported, and no mortality of coral reefs has been observed on the new transplant site, but they will be continuing to monitor the new transplant site to see how potential environmental impacts (i.e. ocean acidification) will harm the overall reef mortality rate. While trying to attach the coral to the new transplant site, they found the coral placed on hard rock is growing considerably well, and coral was even growing on the wires that attached the transplant corals to the transplant site. This gives new hope to future research on coral reef transplant sites. As a result of this coral restoration project, no environmental effects were seen from the transplantation process, no recreational activities were decreased, and no scenic areas were affected by the project. This is a great example that coral transplantation and restoration can work and thrive under the right conditions, which means there may be hope for other damaged coral reefs.[107]

Another possibility for coral restoration is gene therapy. Through infecting coral with genetically modified bacteria, it may be possible to grow corals that are more resistant to climate change and other threats.[108]

Reefs in the past

Throughout Earth history, from a few thousand years after hard skeletons were developed by marine organisms, there were almost always reefs. The times of maximum development were in the Middle Cambrian (513–501 Ma), Devonian (416–359 Ma) and Carboniferous (359–299 Ma), owing to order Rugosa extinct corals, and Late Cretaceous (100–65 Ma) and all Neogene (23 Ma–present), owing to order Scleractinia corals.

Not all reefs in the past were formed by corals: those in the Early Cambrian (542–513 Ma) resulted from calcareous algae and archaeocyathids (small animals with conical shape, probably related to sponges) and in the Late Cretaceous (100–65 Ma), when there also existed reefs formed by a group of bivalves called rudists; one of the valves formed the main conical structure and the other, much smaller valve acted as a cap.

See also

Notes

- ^ Spalding MD and Grenfell AM (1997). "New estimates of global and regional coral reef areas". Coral Reefs. 16 (4): 225. doi:10.1007/s003380050078.

- ^ a b c d e Spalding, Mark, Corinna Ravilious, and Edmund Green (2001). World Atlas of Coral Reefs. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press and UNEP/WCMC ISBN 0520232550.

- ^ Mulhall M (2007) Saving rainforests of the sea: An analysis of international efforts to conserve coral reefs Duke Environmental Law and Policy Forum 19:321–351.

- ^ Hoover, John (November 2007). Hawaiʻi's Sea Creatures. Mutual. ISBN 1-56647-220-2.

- ^ "Corals reveal impact of land use". ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies. Retrieved July 12, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Minato, Charissa (July 1, 2002). "Urban runoff and coastal water quality being researched for effects on coral reefs" (PDF). Retrieved December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Coastal Watershed Factsheets – Coral Reefs and Your Coastal Watershed". Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water. July 1998. Retrieved December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|epa=ignored (help) - ^ Kleypas, Joanie (September 21, 2010). "Coral reef". The Encyclopedia of Earth. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1842). "The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs. Being the first part of the geology of the voyage of the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. during the years 1832 to 1836". London: Smith Elder and Co.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Gordon Chancellor (2008). "Introduction to Coral reefs". Darwin Online. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Animation of coral atoll formation NOAA Ocean Education Service. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c Anderson, Genny (2003). "htm Coral Reef Formation". Marinebio.net. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2006). "A "big picture" view of the Great Barrier Reef" (PDF). Reef Facts for Tour Guides. Retrieved June 18, 2007.

- ^ a b Tobin, Barry (1998, revised 2003). "How the Great Barrier Reef was formed". Australian Institute of Marine Science. Retrieved November 22, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ CRC Reef Research Centre Ltd. "What is the Great Barrier Reef?". Retrieved May 28, 2006.

- ^ Four Types of Coral Reef Microdocs, Stanford Education. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ MSN Encarta (2006). Great Barrier Reef. Archived from the original on October 31, 2009. Retrieved December 11, 2006.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Murphy, Richard C. (2002). Coral Reefs: Cities Under The Seas. The Darwin Press, Inc. ISBN 0-87850-138-X.

- ^

Smithers, S.G. and Woodroffe, C.D. (2000). "Microatolls as sea-level indicators on a mid-ocean atoll". Marine Geology. 168 (1–4): 61–78. doi:10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00043-8.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Moyle & Cech 2003, p. 556

- ^ Connell, Joseph H. (March 24, 1978). "Diversity in Tropical Rain Forests and Coral Reefs". Science. 199 (4335): 1302–1310. doi:10.1126/science.199.4335.1302. PMID 17840770.

- ^ UNEP (2001) UNEP-WCMC World Atlas of Coral Reefs Coral Reef Unit

- ^ Achituv, Y. and Dubinsky, Z. 1990. Evolution and Zoogeography of Coral Reefs Ecosystems of the World. Vol. 25:1–8.

- ^ a b Wells, Sue; Hanna, Nick (1992). Greenpeace Book of Coral Reefs. Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8069-8795-2.

- ^ Vajed Samiei, J. (3). "Some Scleractinian Corals (Class: Anthozoa) of Larak Island, Persian Gulf". Zootaxa. 3636 (1): 101–143. doi:10.11646%2Fzootaxa.3636.1.5.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gunnerus, Johan Ernst (1768). Om Nogle Norske Coraller.

- ^ a b Nybakken, James. 1997. Marine Biology: An Ecological Approach. 4th ed. Menlo Park, CA: Addison Wesley.

- ^ NOAA CoRIS – Regional Portal – Florida. Coris.noaa.gov (August 16, 2012). Retrieved on March 3, 2013.

- ^ NGM.natinalgeographic.com, Ultra Marine: In far eastern Indonesia, the Raja Ampat islands embrace a phenomenal coral wilderness, by David Doubilet, National Geographic, September 2007

- ^ Sherman, C.D.H. "The Importance of Fine-scale Environmental Heterogeneity in Determining Levels of Genotypic Diversity and Local Adaption." University of Wollongong Ph.D. Thesis. 2006. Accessed June 7, 2009.

- ^ Marshall, Paul; Schuttenberg, Heidi (2006). A Reef Manager’s Guide to Coral Bleaching. Townsville, Australia: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. ISBN 1-876945-40-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stacy, J., Marion, G., McCulloch, M. and Hoegh-Guldberg, O. "changes to Mackay Whitsunday water quality and connectivity between terrestrial, mangrove and coral reef ecosystems: Clues from coral proxies and remote sensing records -Synthesis of research from an ARC Linkage Grant (2004–2007)." University of Queensland – Centre for Marine Studies. May 2007. Accessed June 7, 2009.

- ^ Nothdurft, L.D. "Microstructure and early diagenesis of recent reef building scleractinian corals, Heron Reef, Great Barrier Reef: Implications for palaeoclimate analysis." Queensland University of Technology Ph.D. Thesis. 2007. Accessed June 7, 2009.

- ^ Wilson, R.A. "The Biological Notion of Individual."Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. August 9, 2007. Accessed June 7, 2009.

- ^ Jennings S, Kaiser MJ and Reynolds JD (2001) Marine fisheries ecology, Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 291–293. ISBN 978-0-632-05098-7.

- ^ Rougerier, F The functioning of coral reefs and atolls: from paradox to paradigm ORSTOM, Papeete.

- ^ Sorokin, Yuri I. (1993). Coral Reef Ecology. Germany: Sringer-Herlag, Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-0-387-56427-2.

- ^ a b c Castro, Peter and Michael Huber. 2000. Marine Biology. 3rd ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Zooxanthellae… What's That?. Oceanservice.noaa.gov (March 25, 2008). Retrieved on November 1, 2011.

- ^ A Reef Manager’s Guide to Coral Bleaching. Townsville, Australia: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority,. 2006. ISBN 1-876945-40-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Roach, John (November 7, 2001). "Rich Coral Reefs in Nutrient-Poor Water: Paradox Explained?". National Geographic News. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ Nowak. "Corals play rough over Darwin's paradox". New Scientist date=21 September 2002 (2361).

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Missing pipe in:|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Leichter, J. (1996). "Pulsed delivery of subthermocline water to Conch Reef (Florida Keys) by internal tidal bores". Limnology and Oceanography. 41 (7): 1490–1501. doi:10.4319/lo.1996.41.7.1490.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Leichter et al. 1996" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Wolanski, E. (1983). "Upwelling by internal tides and Kelvin waves at the continental shelf break on the Great Barrier Reef. ABSTRACT". Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 34: 65–80. doi:10.1071/MF9830065.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Leichter, J. (2006). "Variation beneath the surface: Quantifying complex thermal environments on coral reefs in the Caribbean, Bahamas and Florida". Journal of Marine Research. 64 (4): 563–588. doi:10.1357/002224006778715711.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ezer, T. (2011). "Modeling and observations of high-frequency flow variability and internal waves at a Caribbean reef spawning aggregation site". Ocean Dynamics. 61 (5): 581–598. doi:10.1007/s10236-010-0367-2.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fratantoni, D. (2006). "The Evolution and Demise of North Brazil Current Rings". Journal of Physical Oceanography. 36 (7): 1241–1249. doi:10.1175/JPO2907.1.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Leichter, J. (1998). "Breaking internal waves on a Florida (USA) coral reef: a plankton pump at work?". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 166: 83–97. doi:10.3354/meps166083.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Leichter et al. 1998" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Talley, L. (2011). Descriptive Physical Oceanography: An Introduction. Oxford UK: Elsevier Inc.

- ^ Helfrich, K. (1992). "Internal solitary wave breaking and run-up on a uniform slope. ABSTRACT". Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 243: 133–154. doi:10.1017/S0022112092002660.

- ^ Gregg, M. (1989). "Scaling turbulent dissipation in the thermocline. ABSTRACT". Journal of Geophysical Research. 9686–9698. 94: 9686. doi:10.1029/JC094iC07p09686.

- ^ Taylor, J. (1992). "The energetics of breaking events in a resonantly forced internal wave field. ABSTRACT". Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 239: 309–340. doi:10.1017/S0022112092004427.

- ^ Andrews, J. (1982). "Upwelling as a source of nutrients for the Great Barrier Reef ecosystems: A solution to Darwin's question?". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 8: 257–269. doi:10.3354/meps008257.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sandstrom, H. (1984). "Internal tide and solitons on the Scotian shelf: A nutrient pump at work. ABSTRACT". Journal of Geophysical Research. 89: 6415–6426. doi:10.1029/JC089iC04p06415.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Wolanski, E. (1988). "Topographically controlled fronts in the ocean and their biological significance". Science. 241 (4862): 177–181. doi:10.1126/science.241.4862.177. PMID 17841048.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Wolanski and Hamner 1988" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Rougerie, F. (1992). "Geothermal endo-upwelling: A solution to the reef nutrient paradox?". Continental Shelf Research. 12 (7–8): 785–798. doi:10.1016/0278-4343(92)90044-K.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wolanski, E. (1993). "Upwelling by internal waves, Tahiti, French Polynesia". Continental Shelf Research. 15 (2–3): 357–368. doi:10.1016/0278-4343(93)E0004-R.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Szmant, A. (1996). "Water column and sediment nitrogen and phosphorus distribution patterns in the Florida Keys, USA. ABSTRACT". Coral Reefs. 15: 21–41.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Furnas, M. (1996). "Nutrient inputs into the central Great Barrier Reef (Australia) from subsurface intrusions of Coral Sea waters: A two-dimensional displacement model. Continental Shelf Research". 16: 1127–1148.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Leichter, J. (1999). "Predicting high-frequency upwelling: Spatial and temporal patterns of temperature anomalies on a Florida coral reef. Continental Shelf Research". 19: 911–928.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Leichter, J. (2003). "Episodic nutrient transport to Florida coral reefs". Limnology and Oceanography. 48 (4): 1394–1407. doi:10.4319/lo.2003.48.4.1394.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Leichter, J. (2005). "Spatial and Temporal Variability of Internal Wave Forcing on a Coral Reef". Journal of Physical Oceanography. 35 (11): 1945–1962. doi:10.1175/JPO2808.1.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Smith, J. (2004). "Nutrient and growth dynamics of Halimeda tuna on Conch Reef, Florida Keys: Possible influence of internal tides on nutrient status and physiology". Limnology and Oceanography. 49 (6): 1923–1936. doi:10.4319/lo.2004.49.6.1923.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Pineda, J. (1994). "Internal tidal bores in the nearshore: Warm-water fronts, seaward gravity currents and the onshore transport of neustonic larvae". Journal of Marine Research. 52 (3): 427–458. doi:10.1357/0022240943077046.

- ^ Wilson, E (2004). "Coral's Symbiotic Bacteria Fluoresce, Fix Nitrogen". Chemical and engineering news. 82 (33): 7.

- ^ Barnes, R.S.K.; Mann, K.H. (1991). Fundamentals of Aquatic Ecology. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 217–227. ISBN 0-632-02983-8. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hatcher, B.G. Johannes, R.E.; Robertson, A.J. (1989). "Conservation of Shallow-water Marine Ecosystems". Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review. Vol. 27. Routledge. p. 320. ISBN 0-08-037718-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "World's Reef Fishes Tussling With Human Overpopulation". ScienceDaily. April 5, 2011.

- ^ "Coral Reef Biology". NOAA. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ^ Glynn, P.W. (1990). Dubinsky, Z. (ed.). Ecosystems of the World v. 25-Coral Reefs. New York, NY: Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-444-87392-7.

- ^ Vroom, Peter S.; Page, Kimberly N.; Kenyon, Jean C.; Brainard, Russell E. (2006). "Algae-Dominated Reefs". American Scientist. 94 (5): 430–437. doi:10.1511/2006.61.1004.

- ^ Kaplan, Matt (2009). "How the sponge stays slim". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2009.1088.

- ^ Buchheim, Jason. "Coral Reef Fish Ecology". marinebiology.org. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ McClellan, Kate; Bruno, John (2008). "Coral degradation through destructive fishing practices". Encyclopedia of Earth. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- ^ Osborne, Patrick L. (2000). Tropical Ecosystem and Ecological Concepts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 464. ISBN 0-521-64523-9.

- ^ The.honoluluadvertiser.com. The.honoluluadvertiser.com (January 17, 2005). Retrieved on November 1, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service – Birds of Midway Atoll". Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- ^ "Heat Stress to Caribbean Corals in 2005 Worst on Record". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. November 15, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ a b "The Importance of Coral to People". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ "Coastal Capital: Economic Valuation of Coastal Ecosystems in the Caribbean". World Resources Institute.

- ^ Cooper, Emily; Burke, Lauretta; Bood, Nadia (2008). "Coastal Capital: Belize: The Economic Contribution of Belize's Coral Reefs and Mangroves" (PDF). Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ^ a b "Coral reefs around the world". Guardian.co.uk. September 2, 2009.

- ^ Liz Minchin (8). "Air pollution casts a cloud over coral reef growth". The Conversation. The Conversation Media Group. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Clapham ME and Payne (2011). "Acidification, anoxia, and extinction: A multiple logistic regression analysis of extinction selectivity during the Middle and Late Permian". Geology. 39 (11): 1059. doi:10.1130/G32230.1.

- ^ Payne JL and Clapham ME (2012). "End-Permian Mass Extinction in the Oceans: An Ancient Analog for the Twenty-First Century?". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 40: 89. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-042711-105329.

- ^ Life in the Sea Found Its Fate in a Paroxysm of Extinction New York Times, April 30, 2012.

- ^ Losing Our Coral Reefs – Eco Matters – State of the Planet. Blogs.ei.columbia.edu. Retrieved on November 1, 2011.

- ^ Ritter, Karl (December 8, 2010). −goal-coral-reefs.html "Climate goal may spell end for some coral reefs". Associated Press. Retrieved December 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Markey, Sean (May 16, 2006). "Global Warming Has Devastating Effect on Coral Reefs, Study Shows". National Geographic News.

- ^ Kleypas, J.A.; Feely, R.A.; Fabry, V.J.; Langdon, C.; Sabine, C.L.; Robbins (2006). "Impacts of Ocean Acidification on Coral Reefs and Other Marine Calcifiers: A guide for Future Research" (PDF). National Science Foundation, NOAA, & United States Geological Survey. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|first6=missing|last6=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Save Our Seas, 1997 Summer Newsletter, Dr. Cindy Hunter and Dr. Alan Friedlander

- ^ Tun, K.; Chou, L.M.; Cabanban, A.; Tuan, V.S.; Philreefs; Yeemin, T.; Suharsono; Sour, K.; Lane, D. (2004). "Status of Coral Reefs, Coral Reef Monitoring and Management in Southeast Asia, 2004". In Wilkinson, C. (ed.). Status of Coral Reefs of the world: 2004 (PDF). Townsville, Queensland, Australia: Australian Institute of Marine Science. pp. 235–276.

- ^ "Reefs at Risk Revisited" (PDF). World Resources Institute. February 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ Lamb, Joleah (August 16, 2011). "Using coral disease prevalence to assess the effects of concentrating tourism activities on offshore reefs in a tropical marine park". Conservation Biology. 25 (5): 1044–1052. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01724.x. PMID 21848962.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Phoenix Rising". National Geographic Magazine. January 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- ^ Kelly, R.P; Foley; Fisher, WS; Feely, RA; Halpern, BS; Waldbusser, GG; Caldwell, MR; et al. (2011). "Mitigating local causes of ocean acidification with existing laws". Science. 332 (6033): 1036–1037. doi:10.1126/science.1203815. PMID 21617060.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first2=(help) - ^ "Great Barrier Reef Climate Change Action Plan 2007–2011" (PDF). Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. 2007.

- ^ Cinner, Joshua E.; MARNANE, Michael J.; McClanahan, Tim R. (2005). "Conservation and community benefits from traditional coral reef management at Ahus Island, Papua New Guinea". Conservation Biology. 19 (6): 1714–1723. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00209.x-i1.

- ^ "Coral Reef Management, Papua New Guinea". Nasa's Earth Observatory. Retrieved November 2, 2006.

- ^ Horoszowski-Fridman, YB, Izhaki, I & Rinkevich, B (2011). "Engineering of coral reef larval supply through transplantation of nursery-farmed gravid colonies". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 399 (2): 162–166. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2011.01.005.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pomeroy, RS, Parks, JE and Balboa, CM (2006). "Farming the reef: is aquaculture a solution for reducing fishing pressure on coral reefs?". Marine Policy. 30 (2): 111–130. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2004.09.001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rinkevich, B (2008). "Management of coral reefs: We have gone wrong when neglecting active reef restoration" (PDF). Marine pollution bulletin. 56 (11): 1821–1824. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.08.014. PMID 18829052.

- ^ Ferse, SCA (2010). "Poor Performance of Corals Transplanted onto Substrates of Short Durability". Restoration Ecology. 18 (4): 399–407. doi:10.1111/j.1526-100X.2010.00682.x.

- ^ Superglue used for placement of coral. coralgarden.co.uk (May 8, 2009). Retrieved on November 8, 2011.

- ^ Needle and thread use with soft coral. coralgarden.co.uk (May 8, 2009). Retrieved on November 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Sabater, Marlowe G.; Yap, Helen T. (2004). "Long-term effects of induced mineral accretion on growth, survival, and corallite properties of Porites cylindrica Dana" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 311 (2): 355–374. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2004.05.013.

- ^ Jokeil, P.L.; Ku’lei, S.R (2004). "Coral Relocation Project in Kaneohe Bay, Oahu, Hawaii: Report on Phase 1" (PDF). University of Hawaii.

- ^ "Gene Therapy Could Help Corals Survive Climate Change". Scientific American. February 29, 2012.

References

- Butler, Steven. 1996. "Rod? Reel? Dynamite? A tough-love aid program takes aim at the devastation of the coral reefs". U.S. News and World Report, November 25, 1996.

- Christie, P. 2005a. University of Washington, Lecture. May 18, 2005.

- Christie, P. 2005b. University of Washington, Lecture. May 4, 2005.

- Clifton, Julian (2003). "Prospects for Co-Management in Indonesia's Marine Protected Areas". Marine Policy. 27 (5): 389–395. doi:10.1016/S0308-597X(03)00026-5.

- Courtney, Catherine and Alan White. 2000. Integrated Coastal Management in the Philippines. Coastal Management; Taylor and Francis.

- Fox, Helen. 2005. Experimental Assessment of Coral Reef Rehabilitation Following Blast Fishing. The Nature Conservancy Coastal and Marine Indonesia Program. Blackwell Publishers Ltd, February 2005.

- Gjertsen, Heidi. 2004. Can Habitat Protection Lead to Improvements in Human Well-Being? Evidence from Marine Protected Areas in the Philippines.

- Moyle, PB; Cech, JJ (2003). Fishes, An Introduction to Ichthyology (5 ed.). Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-13-100847-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sadovy, Y.J. Ecological Issues and the Trades in Live Reef Fishes, Part 1

- Coral Reef Protection: What Are Coral Reefs?. US EPA.

- UNEP. 2004. Coral Reefs in the South China Sea. UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical Publication No. 2.

- UNEP. 2007. Coral Reefs Demonstration Sites in the South China Sea. UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical Publication No. 5.

- UNEP, 2007. National Reports on Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea. UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical Publication No. 11.

External links

| External image | |

|---|---|

- Coral Reefs- At the Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- How Coral Reefs Work

- International Coral Reef Initiative

- International Year of the Reef in 2008

- Moorea Coral Reef Long Term Ecological Research Site (US NSF)

- ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies

- NOAA's Coral-List Listserver for Coral Reef Information and News

- NOAA's Coral Reef Conservation Program

- Exhibition of the Mexican Caribbean coral reef biodiversity aquarium in Xcaret Mexico

- NOAA's Coral Reef Information System

- ReefBase: A Global Information System on Coral Reefs

- National Coral Reef Institute Nova Southeastern University

- Marine Aquarium Council

- NCORE National Center for Coral Reef Research University of Miami

- Science and Management of Coral Reefs in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

- NBII portal on coral reefs

- Microdocs: 4 kinds of Reef & Reef structure

- Reefrelieffounders.com: Coral reef resources, images, education, threats, solutions

- Images Coral Reef of Gulf of Kutch

- Seminar on Corals and Coral Reefs by Nancy Knowlton (Smithsonian)

- "In The Turf War Against Seaweed, Coral Reefs More Resilient Than Expected". Science Daily. June 3, 2009. Retrieved February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)