Ragnarök

In Norse mythology, Ragnarök (UK: /ˈræɡnərɜːk/,[2] US: /ˈrɑːɡnərɒk/,[3]) is a series of future events, including a great battle foretold to ultimately result in the death of a number of major figures (including the gods Odin, Thor, Týr, Freyr, Heimdallr, and Loki), the occurrence of various natural disasters, and the subsequent submersion of the world in water. Afterward, the world will resurface anew and fertile, the surviving and returning gods will meet, and the world will be repopulated by two human survivors. Ragnarök is an important event in the Norse canon, and has been the subject of scholarly discourse and theory.

The event is attested primarily in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. In the Prose Edda, and a single poem in the Poetic Edda, the event is referred to as Ragnarök or Ragnarøkkr (Old Norse "Fate of the Gods" or "Twilight of the Gods" respectively), a usage popularized by 19th-century composer Richard Wagner with the title of the last of his Der Ring des Nibelungen operas, Götterdämmerung (1876).

Etymology

The Old Norse word "ragnarök" is a compound of two words. Ragna means "conjure" and is used metonymically to refer to beings, most notably creator-gods, who possess the power of conjuring as an attribute. The second word, rök, has several meanings, such as "development, origin, cause, relation, fate." The traditional interpretation is that prior to the merging of /ǫ/ and /ø/ in Icelandic (ca. 1200) the word was rök, derived from Proto-Germanic *rakō.[4] The word ragnarök as a whole is then usually interpreted as the "final destiny of the gods."[5] In 2007, Haraldur Bernharðsson proposed that the original form of the second word in the compound is røk, leading to a Proto-Germanic reconstruction of *rekwa and opening up other semantic possibilities.[6]

In stanza 39 of the Poetic Edda poem Lokasenna, and in the Prose Edda, the form ragnarøk(k)r appears, røk(k)r meaning "twilight." Ragna means conjure, roekrs means caring ("conjure caring the voices of the victory gods"). It has often been suggested that this indicates a misunderstanding or a learned reinterpretation of the original form ragnarök.[4] Haraldur Bernharðsson argues instead that the words ragnarök and ragnarøkkr are closely related, etymologically and semantically, and suggests a meaning of "renewal of the divine powers."[7] Usage of this form was popularized in modern popular culture by 19th-century composer Richard Wagner by way of the title of the last of his Der Ring des Nibelungen operas, Götterdämmerung.[8]

Other terms used to refer to the events surrounding Ragnarök in the Poetic Edda include aldar rök (aldar means age, "end of an age") from stanza 39 of Vafþrúðnismál, tíva rök from stanzas 38 and 42 of Vafþrúðnismál, þá er regin deyja ("when the gods die") from Vafþrúðnismál stanza 47, unz um rjúfask regin ("when the gods will be destroyed") from Vafþrúðnismál stanza 52, Lokasenna stanza 41, and Sigrdrífumál stanza 19, aldar rof ("destruction of the age") from Helgakviða Hundingsbana II stanza 41, regin þrjóta ("end of the gods") from Hyndluljóð stanza 42, and, in the Prose Edda, þá er Muspellz-synir herja ("when the sons of Muspell move into battle") can be found in chapters 18 and 36 of Gylfaginning.[5]

Attestations

Poetic Edda

The Poetic Edda contains various references to Ragnarök:

Völuspá

In the Poetic Edda poem Völuspá, references to Ragnarök begin from stanza 40 until 58, with the rest of the poem describing the aftermath. In the poem, a völva recites information to Odin. In stanza 41, the völva says:

|

Old Norse:

|

English:

|

The völva then describes three roosters crowing: In stanza 42, the jötunn herdsman Eggthér sits on a mound and cheerfully plays his harp while the crimson rooster Fjalar (Old Norse "hider, deceiver"[10]) crows in the forest Gálgviðr. The golden rooster Gullinkambi crows to the Æsir in Valhalla, and the third, unnamed soot-red rooster crows in the halls of the underworld location of Hel in stanza 43.[11]

After these stanzas, the völva further relates that the hound Garmr produces deep howls in front of the cave of Gnipahellir. Garmr's bindings break and he runs free. The völva describes the state of humanity:

|

|

The "sons of Mím" are described as being "at play", though this reference is not further explained in surviving sources.[13] Heimdall raises the Gjallarhorn into the air and blows deeply into it, and Odin converses with Mím's head. The world tree Yggdrasil shudders and groans. The jötunn Hrym comes from the east, his shield before him. The Midgard serpent Jörmungandr furiously writhes, causing waves to crash. "The eagle shrieks, pale-beaked he tears the corpse," and the ship Naglfar breaks free thanks to the waves made by Jormungandr and sets sail from the east. The fire jötnar inhabitants of Muspelheim come forth.[14]

The völva continues that Jötunheimr, the land of the jötnar, is aroar, and that the Æsir are in council. The dwarves groan by their stone doors.[12] Surtr advances from the south, his sword brighter than the sun. Rocky cliffs open and the jötnar women sink.[15] People walk the road to Hel and heavens split apart.

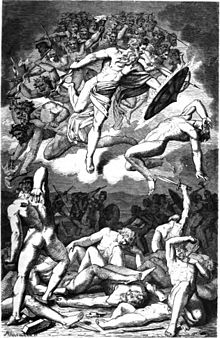

The gods then do battle with the invaders: Odin is swallowed whole and alive fighting the wolf Fenrir, causing his wife Frigg her second great sorrow (the first being the death of her son, the god Baldr).[16] The god Freyr fights Surtr and loses. Odin's son Víðarr avenges his father by rending Fenrir's jaws apart and stabbing it in the heart with his spear, thus killing the wolf. The serpent Jörmungandr opens its gaping maw, yawning widely in the air, and is met in combat by Thor. Thor, also a son of Odin and described here as protector of the earth, furiously fights the serpent, defeating it, but Thor is only able to take nine steps afterward before collapsing. After this, people flee their homes, and the sun becomes black while the earth sinks into the sea, the stars vanish, steam rises, and flames touch the heavens.[17]

The völva sees the earth reappearing from the water, and an eagle over a waterfall hunting fish on a mountain. The surviving Æsir meet together at the field of Iðavöllr. They discuss Jörmungandr, great events of the past, and the runic alphabet. In stanza 61, in the grass, they find the golden game pieces that the gods are described as having once happily enjoyed playing games with long ago (attested earlier in the same poem). The reemerged fields grow without needing to be sown. The gods Höðr and Baldr return from Hel and live happily together.[18]

The völva says that the god Hœnir chooses wooden slips for divination, and that the sons of two brothers will widely inhabit the windy world. She sees a hall thatched with gold in Gimlé, where nobility will live and spend their lives pleasurably.[18] Stanzas 65, found in the Hauksbók version of the poem, refers to a "powerful, mighty one" that "rules over everything" and who will arrive from above at the court of the gods (Old Norse regindómr),[19] which has been interpreted as a Christian addition to the poem.[20] In stanza 66, the völva ends her account with a description of the dragon Níðhöggr, corpses in his jaws, flying through the air. The völva then "sinks down."[21] It is unclear if stanza 66 indicates that the völva is referring to the present time or if this is an element of the post-Ragnarök world.[22]

Vafþrúðnismál

The Vanir god Njörðr is mentioned in relation to Ragnarök in stanza 39 of the poem Vafþrúðnismál. In the poem, Odin, disguised as "Gagnráðr" faces off with the wise jötunn Vafþrúðnir in a battle of wits. Vafþrúðnismál references Njörðr's status as a hostage during the earlier Æsir-Vanir War, and that he will "come back home among the wise Vanir" at "the doom of men."[23]

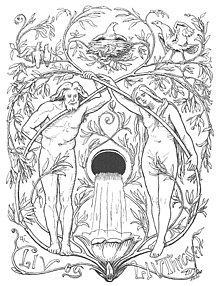

In stanza 44, Odin poses the question to Vafþrúðnir as to who of mankind will survive the "famous" Fimbulvetr ("Mighty Winter"[24]). Vafþrúðnir responds in stanza 45 that those survivors will be Líf and Lífþrasir, and that they will hide in the forest of Hoddmímis holt, that they will consume the morning dew, and will produce generations of offspring. In stanza 46, Odin asks what sun will come into the sky after Fenrir has consumed the sun that exists. Vafþrúðnir responds that Sól will bear a daughter before Fenrir assails her, and that after Ragnarök this daughter will continue her mother's path.[25]

In stanza 51, Vafþrúðnir states that, after Surtr's flames have been sated, Odin's sons Víðarr and Váli will live in the temples of the gods, and that Thor's sons Móði and Magni will possess the hammer Mjolnir. In stanza 52, the disguised Odin asks the jötunn about Odin's own fate. Vafþrúðnir responds that "the wolf" will consume Odin, and that Víðarr will avenge him by sundering its cold jaws in battle. Odin ends the duel with one final question: what did Odin say to his son before preparing his funeral pyre? With this, Vafþrúðnir realizes that he is dealing with none other than Odin, whom he refers to as "the wisest of beings," adding that Odin alone could know this.[26] Odin's message has been interpreted as a promise of resurrection to Baldr after Ragnarök.[27]

Helgakviða Hundingsbana II

Ragnarök is briefly referenced in stanza 40 of the poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana II. Here, the valkyrie Sigrún's unnamed maid is passing the deceased hero Helgi Hundingsbane's burial mound. Helgi is there with a retinue of men, surprising the maid. The maid asks if she is witnessing a delusion since she sees dead men riding, or if Ragnarök has occurred. In stanza 41, Helgi responds that it is neither.[28]

Prose Edda

Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda quotes heavily from Völuspá and elaborates extensively in prose on the information there, though some of this information conflicts with that provided in Völuspá.

Gylfaginning chapters 26 and 34

In the Prose Edda book Gylfaginning, various references are made to Ragnarök. Ragnarök is first mentioned in chapter 26, where the throned figure of High, king of the hall, tells Gangleri (King Gylfi in disguise) some basic information about the goddess Iðunn, including that her apples will keep the gods young until Ragnarök.[29]

In chapter 34, High describes the binding of the wolf Fenrir by the gods, causing the god Týr to lose his right hand, and that Fenrir remains there until Ragnarök. Gangleri asks High why, since the gods could only expect destruction from Fenrir, they did not simply kill Fenrir once he was bound. High responds that "the gods hold their sacred places and sanctuaries in such respect that they chose not to defile them with the wolf's blood, even though the prophecies foretold that he would be the death of Odin."[30]

As a consequence of his role in the death of the god Baldr, Loki (described as father of Fenrir) is bound on top of three stones with the internal organs of his son Narfi (which are turned into iron) in three places. There, venom drops onto his face periodically from a snake placed by the jötunn Skaði, and when his wife Sigyn empties the bucket she is using to collect the dripping venom, the pain he experiences causes convulsions, resulting in earthquakes. Loki is further described as being bound this way until the onset of Ragnarök.[31]

Gylfaginning chapter 51

Chapter 51 provides a detailed account of Ragnarök interspersed with various quotes from Völuspá, while chapters 52 and 53 describe the aftermath of these events. In Chapter 51, High states the first sign of Ragnarök will be Fimbulvetr, during which time three winters will arrive without a summer, and the sun will be useless. High details that, prior to these winters, three earlier winters will have occurred, marked with great battles throughout the world. During this time, greed will cause brothers to kill brothers, and fathers and sons will suffer from the collapse of kinship bonds. High then quotes stanza 45 of Völuspá. Next, High describes that the wolf will first swallow the sun, and then his brother the moon, and mankind will consider the occurrence as a great disaster resulting in much ruin. The stars will disappear. The earth and mountains will shake so violently that the trees will come loose from the soil, the mountains will topple, and all restraints will break, causing Fenrir to break free from his bonds.[32]

High relates that the great serpent Jörmungandr, also described as a child of Loki in the same source, will breach land as the sea violently swells onto it. The ship Naglfar, described in the Prose Edda as being made from the human nails of the dead, is released from its mooring, and sets sail on the surging sea, steered by a jötunn named Hrym. At the same time, Fenrir, eyes and nostrils spraying flames, charges forward with his mouth wide open, his upper jaw reaching to the heavens, his lower jaw touching the earth. At Fenrir's side, Jörmungandr sprays venom throughout the air and the sea.[33]

During all of this, the sky splits into two. From the split, the "sons of Muspell" ride forth. Surtr rides first, surrounded by flames, his sword brighter than the sun. High says that "Muspell's sons" will ride across Bifröst, described in Gylfaginning as a rainbow bridge, and that the bridge will then break. The sons of Muspell (and their shining battle troop) advance to the field of Vígríðr, described as an expanse that reaches "a hundred leagues in each direction," where Fenrir, Jörmungandr, Loki (followed by "Hel's own"), and Hrym (accompanied by all frost jötnar) join them. While this occurs, Heimdallr stands and blows the Gjallarhorn with all his might. The gods awaken at the sound, and they meet. Odin rides to Mímir's Well in search of counsel from Mímir. Yggdrasil shakes, and everything, everywhere fears.[33]

High relates that the Æsir and the Einherjar dress for war and head to the field. Odin, wearing a gold helmet and an intricate coat of mail, carries his spear Gungnir and rides before them. Odin advances against Fenrir, while Thor moves at his side, though Thor is unable to assist Odin because he has engaged Jörmungandr in combat. According to High, Freyr fiercely fights with Surtr, but Freyr falls because he lacks the sword he once gave to his messenger, Skirnir. The hound Garmr (described here as the "worst of monsters") breaks free from his bonds in front of Gnipahellir, and fights the god Týr, resulting in both of their deaths.[34]

Thor kills Jörmungandr, yet is poisoned by the serpent, and manages to walk nine steps before falling to the earth dead. Fenrir swallows Odin, though immediately afterward his son Víðarr kicks his foot into Fenrir's lower jaw, grips Fenrir's upper jaw, and rips apart Fenrir's mouth, killing Fenrir. Loki fights Heimdallr, and the two kill one another. Surtr covers the earth in fire, causing the entire world to burn. High quotes stanzas 46 to 47 of Völuspá, and additionally stanza 18 of Vafþrúðnismál (the latter relating information about the battlefield Vígríðr).[35]

Gylfaginning chapters 52 and 53

At the beginning of chapter 52, Gangleri asks "what will be after heaven and earth and the whole world are burned? All the gods will be dead, together with the Einherjar and the whole of mankind. Didn't you say earlier that each person will live in some world throughout all ages?"[36]

The figure of Third, seated on the highest throne in the hall, responds that there will be many good places to live, but also many bad ones. Third states that the best place to be is Gimlé in the heavens, where a place exists called Okolnir that houses a hall called Brimir—where one can find plenty to drink. Third describes a hall made of red gold located in Niðafjöll called Sindri, where "good and virtuous men will live."[36] Third further relates an unnamed hall in Náströnd, the beaches of the dead, that he describes as a large repugnant hall facing north that is built from the spines of snakes, and resembles "a house with walls woven from branches;" the heads of the snakes face the inside of the house and spew so much venom that rivers of it flow throughout the hall, in which oath breakers and murderers must wade. Third here quotes Völuspá stanzas 38 to 39, with the insertion of original prose stating that the worst place of all to be is in Hvergelmir, followed by a quote from Völuspá to highlight that the dragon Níðhöggr harasses the corpses of the dead there.[37]

Chapter 53 begins with Gangleri asking if any of the gods will survive, and if there will be anything left of the earth or the sky. High responds that the earth will appear once more from the sea, beautiful and green, where self-sown crops grow. The field Iðavöllr exists where Asgard once was, and, there, untouched by Surtr's flames, Víðarr and Váli reside. Now possessing their father's hammer Mjolnir, Thor's sons Móði and Magni will meet them there, and, coming from Hel, Baldr, and Höðr also arrive. Together, they all sit and recount memories, later finding the gold game pieces the Æsir once owned. Völuspá stanza 51 is then quoted.[38]

High reveals that two humans, Líf and Lífþrasir, will have also survived the destruction by hiding in the wood Hoddmímis holt. These two survivors consume the morning dew for sustenance, and from their descendants the world will be repopulated. Vafþrúðnismál stanza 45 is then quoted. The personified sun, Sól, will have a daughter at least as beautiful as she, and this daughter will follow the same path as her mother. Vafþrúðnismál stanza 47 is quoted, and so ends the foretelling of Ragnarök in Gylfaginning.[39]

Archaeological record

Various objects have been identified as depicting events from Ragnarök.

Thorwald's Cross

Thorwald's Cross, a partially surviving runestone erected at Kirk Andreas on the Isle of Man, depicts a bearded human holding a spear downward at a wolf, his right foot in its mouth, while a large bird sits at his shoulder.[40] Rundata dates it to 940,[41] while Pluskowski dates it to the 11th century.[40] This depiction has been interpreted as Odin, with a raven or eagle at his shoulder, being consumed by Fenrir at Ragnarök.[40][42] On the other side of the stone is a depiction of a large cross and another image parallel to the Odin figure that has been described as Christ triumphing over Satan.[43] These combined elements have led to the cross as being described as "syncretic art"; a mixture of pagan and Christian beliefs.[40]

Gosforth Cross

The Gosforth Cross (920–950), in Cumbria, England, is a standing cross of a typical Anglo-Saxon form, carved on all sides of the long shaft, which is nearly square in section. Apart from panels of ornament, the scenes include a Christian Crucifixion, and possibly another scene in Hell, but the other scenes are generally interpreted as narrative incidents from the Ragnarök story,[44] even by a scholar as cautious of such interpretations as David M. Wilson.[40][45] The Ragnarök battle itself may be depicted on the north side.[46] The cross features various figures depicted in Borre style, including a man with a spear facing a monstrous head, one of whose feet is thrust into the beast's forked tongue and on its lower jaw, while the other is placed against its upper jaw, a scene interpreted as Víðarr fighting Fenrir.[40]

Ledberg stone

The 11th century Ledberg stone in Sweden, similarly to Thorwald's Cross, features a figure with his foot at the mouth of a four-legged beast, and this may also be a depiction of Odin being devoured by Fenrir at Ragnarök.[42] Below the beast and the man is a depiction of a legless, helmeted man, with his arms in a prostrate position.[42] The Younger Futhark inscription on the stone bears a commonly seen memorial dedication, but is followed by an encoded runic sequence that has been described as "mysterious,"[47] and "an interesting magic formula which is known from all over the ancient Norse world."[42]

Skarpåker stone

On the early 11th century Skarpåker Stone, from Södermanland, Sweden, a father grieving his dead son used the same verse form as in the Poetic Edda in the following engraving:

|

|

Jansson (1987) notes that at the time of the inscription, everyone who read the lines would have thought of Ragnarök and the allusion that the father found fitting as an expression of his grief.[48]

Theories and interpretations

Cyclical time

Rudolf Simek theorizes that the survival of Líf and Lífþrasir at the end Ragnarök is "a case of reduplication of the anthropogeny, understandable from the cyclic nature of the Eddic eschatology". Simek says that Hoddmímis holt "should not be understood literally as a wood or even a forest in which the two keep themselves hidden, but rather as an alternative name for the world-tree Yggdrasill. Thus, the creation of mankind from tree trunks (Askr, Embla) is repeated after the Ragnarǫk as well". Simek says that in Germanic regions, the concept of mankind originating from trees is ancient, and additionally points out legendary parallels in a Bavarian legend of a shepherd who lives inside a tree, whose descendants repopulate the land after life there has been wiped out by plague (citing a retelling by F. R. Schröder). In addition, Simek points to an Old Norse parallel in the figure of Örvar-Oddr, "who is rejuvenated after living as a tree-man (Ǫrvar-Odds saga 24–27)".[49]

Muspille, Heliand, and Christianity

Theories have been proposed about the relation to Ragnarök and the 9th century Old High German epic poem Muspilli about the Christian Last Judgment, where the word Muspille appears, and the 9th century Old Saxon epic poem Heliand about the life of Christ, where various other forms of the word appear. In both sources, the word is used to signify the end of the world through fire.[50] Old Norse forms of the term also appear throughout accounts of Ragnarök, where the world is also consumed in flames, and, though various theories exist about the meaning and origins of the term, its etymology has not been solved.[50]

Proto-Indo-European basis

Parallels have been pointed out between the Ragnarök of the Norse pagans and the beliefs of other related Indo-European peoples. Subsequently, theories have been put forth that Ragnarök represents a later evolution of a Proto-Indo-European belief along with other cultures descending from the Proto-Indo-Europeans. These parallels include comparisons of a cosmic winter motif between the Norse Fimbulwinter, the Iranian Bundahishn and Yima.[51] Víðarr's stride has been compared to the Vedic god Vishnu in that both have a "cosmic stride" with a special shoe used to tear apart a beastly wolf.[51] Larger patterns have also been drawn between "final battle" events in Indo-European cultures, including the occurrence of a blind or semi-blind figure in "final battle" themes, and figures appearing suddenly with surprising skills.[51]

Volcanic eruptions

Hilda Ellis Davidson theorizes that the events in Völuspá occurring after the death of the gods (the sun turning black, steam rising, flames touching the heavens, etc.) may be inspired by the volcanic eruptions on Iceland. Records of eruptions on Iceland bear strong similarities to the sequence of events described in Völuspá, especially the eruption at Laki that occurred in 1783.[52] Bertha Phillpotts theorizes that the figure of Surtr was inspired by Icelandic eruptions, and that he was a volcano demon.[53] Surtr's name occurs in some Icelandic place names, among them the lava tube caves Surtshellir, a number of dark caverns in the volcanic central region of Iceland.

Bergbúa þáttr

Parallels have been pointed out between a poem spoken by a jötunn found in the 13th century þáttr Bergbúa þáttr ("the tale of the mountain dweller"). In the tale, Thórd and his servant get lost while traveling to church in winter, and so take shelter for the night within a cave. Inside the cave they hear noises, witness a pair of immense burning eyes, and then the being with burning eyes recites a poem of 12 stanzas. The poem the being recites contains references to Norse mythology (including a mention of Thor) and also prophecies (including that "mountains will tumble, the earth will move, men will be scoured by hot water and burned by fire"). Surtr's fire receives a mention in stanza 10. John Lindow says that the poem may describe "a mix of the destruction of the race of giants and of humans, as in Ragnarök" but that "many of the predictions of disruption on earth could also fit the volcanic activity that is so common in Iceland."[54]

Notes

- ^ Fazio, Moffet, Wodehouse (2003:201).

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. "Ragnarök," http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50196452 (subscription needed) . Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- ^ Collins Dictionary, s.v. "Ragnarok," http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/ragnarok . Retrieved August 16, 2013

- ^ a b See e.g. Bjordvand and Lindemann (2007:856–857). Cite error: The named reference "BJORDVAND856-857" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Simek (2000:259).

- ^ Haraldur Bernharðsson (2007:30–32).

- ^ Haraldur Bernharðsson (2007:35).

- ^ Lindow (2001:254).

- ^ a b Dronke (1997:18).

- ^ Orchard (1997:43).

- ^ Larrington (1996:9).

- ^ a b c Dronke (1997:19).

- ^ Larrington (1996:265).

- ^ Larrington (1996:10).

- ^ Bellows (2004:22).

- ^ Larrington (1996:266).

- ^ Bellows (2004:23).

- ^ a b Larrington (1996:12).

- ^ Simek (2007:262)

- ^ Lindow (2001:257).

- ^ Larrington (1996:13).

- ^ Larrington (1996:3).

- ^ Larrington (1999:46).

- ^ Lindow (2001:115).

- ^ Larrington (1999:47).

- ^ Larrington (1999:48–49).

- ^ Larrington (1999:269).

- ^ Larrington (1999:139).

- ^ Byock (2005:36).

- ^ Byock (2005:42).

- ^ Byock (2005:70).

- ^ Byock (2005:71–72).

- ^ a b Byock (2005:72).

- ^ Byock (2005:73).

- ^ Byock (2005:73–75).

- ^ a b Byock (2005:76).

- ^ Byock (2005:76–77).

- ^ Byock (2005:77).

- ^ Byock (2005:77–78).

- ^ a b c d e f Pluskowski (2004:158).

- ^ Entry Br Olsen;185A in Rundata 2.0

- ^ a b c d Jansson (1987:152)

- ^ Hunter, Ralston (1999:200).

- ^ Bailey, Richard N. (2002). "Scandinavian Myth on Viking-period Stone Sculpture in England". In Barnes, Geraldine; Ross, Margaret Clunies (eds.). Old Norse Myths, Literature, and Society (PDF). Sydney: University of Sydney. pp. 15–23. ISBN 1-86487-316-7.

- ^ Wilson, David M.; Anglo-Saxon: Art From The Seventh Century To The Norman Conquest, pp. 149–150, Thames and Hudson (US edn. Overlook Press), 1984.

- ^ Orchard (1997:13).

- ^ MacLeod, Mees (2006:145).

- ^ Jansson (1987:141)

- ^ Simek (2007:189). For Schröder, see Schröder (1931).

- ^ a b Simek (2007:222–224).

- ^ a b c Mallory, Adams (1997:182–183).

- ^ Davidson (1990:208–209).

- ^ Phillpotts (1905:14 ff.) in Davidson (1990:208).

- ^ Lindow (2001:73–74).

References

- Bellows, Henry Adams (2004). The Poetic Edda: The Mythological Poems. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43710-8

- Bjordvand, Harald; Lindeman, Fredrik Otto (2007). Våre arveord. Novus. ISBN 978-82-7099-467-0.

- Byock, Jesse (Trans.) (2005). The Prose Edda. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044755-5

- Dronke, Ursula (Trans.) (1997). The Poetic Edda: Volume II: Mythological Poems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-811181-9

- Davidson, H. R. Ellis (1990). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-013627-4.

- Fazio, Michael W. Moffett, Marian. Wodehouse, Lawrence (2003). A World History of Architecture. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-07-141751-6

- Haraldur Bernharðsson (2007). "Old Icelandic Ragnarök and Ragnarökkr" in Verba Docenti edited by Alan J. Nussbaum, pp. 25–38. ISBN 0-9747927-3-X

- Hunter, John & Ralston, Ian (1999). The Archaeology of Britain: An Introduction from the Upper Palaeolithic to the Industrial Revolution. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13587-7

- Jansson, Sven B. (1987). Runes in Sweden. Stockholm, Gidlund. ISBN 91-7844-067-X

- Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999). The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0

- Macleod, Mindy. Mees, Bernard (2006). Runic Amulets and Magic Objects. Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-205-4

- Mallory, J.P. Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-884964-98-2

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-34520-2

- Phillpotts, Bertha (1905). "Surt" in Arkiv för Nordisk Filologi, volume 21, pp. 14 ff.

- Pluskowski, Aleks (2004). "Apocalyptic Monsters: Animal Inspirations for the Iconography of Medieval Northern Devourers" as collected in: Bildhauer, Bettina & Mills, Robert. The Monstrous Middle Ages. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8667-5

- Rundata 2.0 for Windows.

- Schapiro, Meyer (1942). "'Cain's Jaw-Bone that Did the First Murder'". The Art Bulletin. 24 (3): 205–12. doi:10.2307/3046829. JSTOR 3046829.

- Schapiro, Meyer (1980). Late Antique, Early Christian and Mediaeval Art. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-2514-1.

- Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-513-1