Down syndrome

| Down syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Medical genetics, neurology |

| Frequency | 0.1% |

Down syndrome (DS) or Down's syndrome, also known as trisomy 21, is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of all or part of a third copy of chromosome 21.[1] It is typically associated with physical growth delays, characteristic facial features and mild to moderate intellectual disability.[2] The average IQ of a young adult with Down syndrome is 50, equivalent to the mental age of an 8 or 9 year old child, but this varies widely.[3]

Down syndrome can be identified during pregnancy by prenatal screening followed by diagnostic testing, or after birth by direct observation and genetic testing. Since the introduction of screening, pregnancies with the diagnosis are often terminated.[4][5] Regular screening for health problems common in Down syndrome is recommended throughout the person's life.

Education and proper care has been shown to improve quality of life.[6] Some children with Down syndrome are educated in typical school classes while others require more specialized education.[7] Some individuals with Down syndrome graduate from high school and a few attend post-secondary education.[8] In adulthood about 20% in the United States do paid work in some capacity[9] with many requiring a sheltered work environment.[7] Support in financial and legal matters is often needed.[10] Life expectancy is around 50 to 60 years in the developed world with proper health care.[3][10]

Down syndrome is the most common chromosome abnormality in humans,[3] occurring in about 1 per 1000 babies born each year.[2] It is named after John Langdon Down, the British doctor who fully described the syndrome in 1866.[11] Some aspects of the condition were described earlier by Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol in 1838 and Édouard Séguin in 1844.[12] The genetic cause of Down syndrome—an extra copy of chromosome 21—was identified by French researchers in 1959.[11]

Signs and symptoms

Those with Down syndrome nearly always have physical and intellectual disabilities.[13] As adults their mental abilities are typically similar to that of an 8 or 9 year old.[3] They also typically have poor immune function[14] and generally reach developmental milestones at a later age.[10] They have an increased risk of a number of other health problems, including: congenital heart disease, leukemia, thyroid disorders, and mental illness, among others.[11]

| Characteristics | Percentage | Characteristics | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental impairment | 99%[15] | Abnormal teeth | 60%[16] |

| Stunted growth | 90%[17] | Slanted eyes | 60%[14] |

| Umbilical hernia | 90%[18] | Shortened hands | 60%[16] |

| Increased skin back of neck | 80%[11] | Short neck | 60%[16] |

| Low muscle tone | 80%[19] | Obstructive sleep apnea | 60%[11] |

| Narrow roof of mouth | 76%[16] | Bent fifth finger tip | 57%[14] |

| Flat head | 75%[14] | Brushfield spots in the iris | 56%[14] |

| Flexible ligaments | 75%[14] | Single transverse palmar crease | 53%[14] |

| Large tongue | 75%[19] | Protruding tongue | 47%[16] |

| Abnormal outer ears | 70%[11] | Congenital heart disease | 40%[16] |

| Flattened nose | 68%[14] | Strabismus | ~35%[2] |

| Separation of 1st and 2nd toes | 68%[16] | Undescended testicles | 20%[20] |

Physical

People with Down syndrome may have some or all of the following physical characteristics: a small chin, slanted eyes, poor muscle tone, a flat nasal bridge, a single crease of the palm, and a protruding tongue due to a small mouth and large tongue.[19] These airway changes lead to obstructive sleep apnea in around half of those with Down syndrome.[11] Other common features include: a flat and wide face,[19] a short neck, excessive joint flexibility, extra space between big toe and second toe, abnormal patterns on the fingertips and short fingers.[16][19] Instability of the atlanto-axial joint occurs in approximately 20% and may lead to spinal cord injury in 1–2%.[3][10] Hip dislocations may occur without trauma in up to a third of people with Down syndrome.[11]

Growth in height is slower resulting in adults who tend to have short stature—the average height for men is 154 cm (5 feet 1 inch) and for women is 142 cm (4 feet 8 inches).[21] Individuals with Down syndrome are at increased risk for obesity as they age.[11] There are growth charts specifically for children with Down syndrome.[11]

Neurological

Most individuals with Down syndrome have mild (IQ: 50–70) or moderate (IQ: 35–50) intellectual disability with some cases having severe (IQ: 20–35) difficulties.[2][22] Those with mosaic Down syndrome typically have IQ scores 10–30 points higher.[23] As they age people with Down syndrome typically perform less well compared to their same-age peers.[22][24] Some after 30 years of age may lose their ability to speak.[3] This syndrome causes about a third of cases of intellectual disability.[14] Many developmental milestones are delayed with the ability to crawl typically occurring around 8 months rather than 5 month and the ability to walk independently typically occurring around 21 months rather than 14 months.[25]

Commonly individuals with Down syndrome have better language understanding than ability to speak.[11][22] Between 10 and 45 percent have either a stutter or rapid and irregular speech, making it difficult to understand them.[26] They typically do fairly well with social skills.[11] Behavior problems are not generally as great an issue as in other syndromes associated with intellectual disability.[22] In children with Down syndrome mental illness occurs in nearly 30% with autism occurring in 5–10%.[10] People with Down syndrome experience a wide range of emotions.[27] While generally happy,[28] symptoms of depression and anxiety may develop in early adulthood.[3]

Children and adults with Down syndrome are at increased risk of epileptic seizures which occur in 5–10% of children and up to 50% of adults.[3] This includes an increased risk of a specific type of seizure called infantile spasms.[11] Many (15%) who live 40 years or longer develop dementia of the Alzheimer's type.[29] In those who reach 60 years of age, 50–70% have the disease.[3]

Senses

Hearing and vision disorders occur in more than half of people with Down syndrome.[11] Vision problems occur in 38 to 80%.[2] Between 20 and 50% have strabismus, in which the two eyes do not move together.[2] Cataracts (cloudiness of the len of the eye) occur in 15%,[10] and may be present at birth.[2] Keratoconus (a thin, cone-shaped corneas)[3] and glaucoma (increased eye pressure) are also more common,[2] as are refractive errors requiring glasses or contacts.[3] Brushfield spots (small white or grayish/brown spots on the outer part of the iris) are present in 38 to 85% of individuals.[2]

Hearing problems are found in 50–90% of children with Down syndrome.[30] This is often the result of otitis media with effusion which occurs in 50–70%[10] and chronic ear infections which occurs in 40 to 60%.[31] Ear infections often begin in the first year of life and are partly due to poor eustachian tube function.[32][33] Excessive ear wax can also cause hearing loss due to obstruction of the outer ear canal.[3] Even a mild degree of hearing loss can have negative consequences for speech, language understanding and academics.[2][33] Additionally, it is important to rule out hearing loss as a factor in social and cognitive deterioration.[34] Age-related hearing loss of the sensorineural type occurs at a much earlier age and affects 10–70%.[3]

Heart

The rate of congenital heart disease in newborns with Down syndrome is around 40%.[16] Of those with heart heart disease about 80% have an atrioventricular septal defect or ventricular septal defect.[3] Mitral valve problems become common as people age, even in those without heart problems at birth.[3] Other problems that may occur include: tetralogy of Fallot and patent ductus arteriosus.[32] People with Down syndrome have a lower risk of hardening of the arteries.[3]

Cancer

Although the overall risk of cancer is not changed;[35] there is an increased risk of leukemia and testicular cancer and a reduced risk of solid cancers.[3] Solid cancers are believed to be less common due to increased expression of tumor suppressor genes present on chromosome 21.[36]

Cancers of the blood are 10 to 15 times more common in children with Down syndrome.[11] In particular, acute lymphoblastic leukemia is 20 times more common and the megakaryoblastic form of acute myelogenous leukemia is 500 times more common.[37] Transient myeloproliferative disease, a disorder of blood cell production that does not occur outside of Down syndrome, affects 3–10% of infants.[37][38] The disorder is typically not serious but occasionally can be.[38] It resolves most times without treatment; however, in those who have had it there is a 20 to 30 percent risk of developing acute lymphoblastic leukemia at a later time.[38]

Endocrine

Problems of the thyroid gland occur in 20–50% of individuals with Down syndrome.[3][11] Low thyroid is the most common form, occurring in almost half of all individuals.[3] Thyroid problems can be due to a poorly or non functioning thyroid at birth (known as congenital hypothyroidism) which occurs in 1%[10] or can develop later due to an attack on the thyroid by the immune system resulting in Graves disease or autoimmune hypothyroidism.[39] Type 1 diabetes mellitus is also more common.[3]

Gastrointestinal

Constipation occurs in nearly half of people with Down syndrome and may result in changes in behavior.[11] One potential cause is Hirschsprung's disease, which is due to a lack of nerve cells controlling the colon, which occurs in 2 to 15%.[40] Other frequent congenital problems include: duodenal atresia, pyloric stenosis, Meckel diverticulum and imperforate anus.[32] Celiac disease affects about 7–20%[3][11] and gastroesophageal reflux disease is also more common.[32]

Fertility

Males with Down syndrome usually do not father children, while females have lower rates of fertility relative those who are unaffected.[41] Fertility is estimated to be present in 30–50% of women.[42] Menopause typically occurs at an earlier age.[3] The poor fertility in men is thought to be due to problems with sperm development; however, it may also be related to not being sexually active.[41] As of 2006 there have been three recorded instances of males with Down syndrome fathering children and 26 cases of women having children.[41] Without assisted reproductive technologies, approximately half of the pregnancies of someone with Down syndrome will also have the syndrome.[41][43]

Genetics

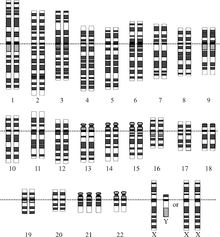

Down syndrome is caused by having three copies of the genes on chromosome 21, rather than the usual two.[1][44] The parents of the affected individual are typically genetically normal.[14] Those who have one child with Down syndrome have about a 1% risk of having a second child with the syndrome, if both parents are found to have normal karyotypes.[42]

The extra chromosome content can arise through several different ways. The most common cause (approximately 92–95% of cases) is a complete extra copy of chromosome 21, resulting in trisomy 21.[43][45] In 1 to 2.5% of cases, some of the cells in the body are normal and others have trisomy 21, known as mosaic Down syndrome.[42][46] The other common mechanisms that can give rise to Down syndrome include: a Robertsonian translocation, isochromosome, or ring chromosome. These contain additional material from chromosome 21 and occur in approximately 2.5% of cases.[11][42] An isochromosome results when the two long arms of a chromosome separate together rather than the long and short arm separating together during egg or sperm development.[43]

Trisomy 21

Trisomy 21 (also known by the karyotype 47,XX,+21 for females and 47,XY,+21 for males)[47] is caused by a failure of the 21st chromosome to separate during egg or sperm development.[43] As a result, a sperm or egg cell is produced with an extra copy of chromosome 21; this cell thus has 24 chromosomes. When combined with a normal cell from the other parent, the embryo and baby has 47 chromosomes, with three copies of chromosome 21.[1][43] About 88% of cases of trisomy 21 result from non separation of the chromosomes in the mother, 8% from non-separation in the father, and 3% after the egg and sperm have merged.[48]

Translocation

The extra chromosome 21 material may also occur due to a Robertsonian translocation in 2–4% cases.[42][49] In this situation, the long arm of chromosome 21 is attached to another chromosome, often chromosome 14.[50] In a male affected with down syndrome it results in a karyotype of 46XY,t(14q21q).[50][51] This may be a new mutation or previously present in one of the parents.[52] The parent with such a translocation is usually normal physically and mentally;[50] however, during production of egg or sperm cells there is a higher chance of creating reproductive cells with extra chromosome 21 material.[49] This results in a 15% chance of having a child with Down syndrome when the mother is affected and a less than 5% risk if the father is affected.[52] The risk of this type of Down syndrome is not related to the mother's age.[50] Some children without Down syndrome may inherit the translocation and have a higher risk of having children of their own with Down syndrome.[50] In this case it is sometimes known as familial Down syndrome.[53]

Mechanism

The extra genetic material present in DS results in over-expression of a portion of the 310 genes located on chromosome 21.[44] This over-expression has been estimated at around 50%.[42] Some research has suggested that the Down syndrome critical region is located at bands 21q22.1–q22.3,[54] with this area including genes for amyloid, superoxide dismutase, and likely the ETS-2 proto oncogene.[55] Other research; however, has not confirmed these findings.[44]

The dementia which occurs in Down syndrome is due to an excess of amyloid beta peptide produced in the brain and is similar to Alzheimer's disease.[56] This peptide is processed from amyloid precursor protein whose gene is located on chromosome 21.[56] Senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are present in nearly all by 35 years of age even though dementia may not be present.[14] Those with DS also lack a normal number of lymphocytes and produce less antibodies which contributes to their increased risk of infection.[11]

Screening

Guidelines recommend that screening for Down syndrome be offered to all pregnant women, regardless of age.[57][58] A number of tests can be used, with varying levels of accuracy. They are usually used in combination to increase the detection rate, while maintaining a low false positive rate.[11] None can be definitive, thus if screening is positive either amniocentesis or chorionic villous sampling is required to confirm the diagnosis.[57] Screening in both the first and second trimesters is better than just screening in the first trimester.[57] The different screening techniques in use are able to pick up 90 to 95% of cases with a false positive rate of between 2 and 5%.[59]

| Screen | Week of pregnancy when performed | Detection rate | False positive | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined test | 10–13.5 wks | 82–87% | 5% | Uses ultrasound to measure nuchal translucency in addition to blood tests for free or total beta-hCG and PAPP-A. |

| Quad screen | 15–20 wks | 81% | 5% | Measures the maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein, unconjugated estriol, hCG, and inhibin-A. |

| Integrated test | 15–20 wks | 94–96%% | 5% | Is a combination of the quad screen, PAPP-A, and NT |

| Cell-free fetal DNA | From 10 wks[60] | 96-100%[61] | 0.3%[62] | A blood sample is taken from the mother by venipuncture and is sent for DNA analysis. |

Ultrasound

Ultrasound imaging can be used to screen for Down syndrome. Findings that indicate increased risk when seen at 14 to 24 weeks of gestation include: a small or no nasal bone, large ventricles, nuchal fold thickness, and an abnormal right subclavian artery, among others.[63] The presence or absence of many markers is more accurate.[63] Increased fetal nuchal translucency (NT) indicates an increased risk of Down syndrome picking up 75–80% of cases and being falsely positive in 6%.[64]

Blood tests

Several blood markers can be measured to predict the risk of Down syndrome during the first or second trimester.[59][65] Testing in both trimesters is sometimes recommended and test results are often combined with ultrasound results.[59] In the second trimester often two or three tests are used in combination with two or three of: α-fetoprotein, unconjugated estriol, total hCG, and free βhCG detecting about 60–70% of cases.[65]

Testing of the mother's blood for fetal DNA is being studied and appears promising in the first trimester.[66][67] The International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis considers it a reasonable screening option for those women whose pregnancies are at a high risk for trisomy 21.[68] Accuracy has been reported at 98.6% in the first trimester of pregnancy.[11] Confirmatory testing by invasive techniques (amniocentesis, CVS) is still required to confirm the screening result.[68]

Diagnosis

Before birth

When screening tests predict a high risk of Down syndrome, a more invasive diagnostic test (amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling) is needed to confirm the diagnosis.[57] If Down syndrome occurs in 1 in 500 pregnancies and the test used has a 5% false positive rate, this means that of 28 women who test positive on screening only 1 will have Down syndrome confirmed.[59] If the screening test has a 2% false positive rate this means that 1 out of 10 who test positive on screening having a fetus with DS.[59] Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling are more reliable; however, they carry an increased risk of miscarriage of between 0.5 and 1%.[69] There is also an increased risk of limb problems in the offspring due to the procedure.[69] The risk from the procedure is greater the earlier it is performed and thus amniocentesis is not recommended before 15 weeks gestational age and chorionic villus sampling before 10 weeks gestational age.[69]

Abortion rates

About 92% of pregnancies in the United Kingdom and Europe with a diagnosis of Down syndrome are terminated.[5] In the United States termination rates are around 67%; however this varies significantly depending upon the population looked at.[4] When non pregnant people are asked if they would have a termination if their fetus tested positive 23–33% said yes, when high risk pregnant women were asked 46–86% said yes, and when women who screen positive are asked 89–97% say yes.[70]

After birth

The diagnosis can often be suspected based on the child's physical appearance at birth.[10] An analysis of the child's chromosomes is needed to confirm the diagnosis and determine if a translocation is present as this may help determine the risk of the child's parents having further children with Down syndrome.[10] Parents generally wish to know the possible diagnosis once it is suspected and do not wish pity.[11]

Management

Efforts such as early childhood intervention, screening for common problems, medical treatment where indicated, a good family environment, and work related training can improve the development of children with Down syndrome. Education and proper care can improve quality of life.[6] Typical childhood vaccinations are recommended.[11]

Health screening

| Testing | Children[71] | Adults[3] |

|---|---|---|

| Hearing | 6 months, 12 months, then yearly | 3–5 years |

| T4 and TSH | 6 months, then yearly | |

| Eyes | 6 months, then yearly | 3–5 years |

| Teeth | 2 years, then every 6 months. | |

| Coeliac disease | Between 2 and 3 years of age, or earlier if symptoms occur. |

|

| Sleep study | 3 to 4 years, or earlier if symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea occur. |

|

| Neck X-rays | Between 3 and 5 years of age |

A number of health organizations have issued recommendations for screening those with Down syndrome for particular diseases.[71] It is recommended that this be done systematically.[11]

At birth all children should get an electrocardiogram and ultrasound of the heart.[11] Surgical repair of heart problems may be required as early as three months of age.[11] Heart valve problems may occur in young adults, and further ultrasound evaluation may be needed in adolescents and in early adulthood.[11] Due to the elevated risk of testicular cancer, some recommend checking the person's testicles yearly.[3]

Cognitive development

Hearing aids or other amplification devices can be useful for language learning in those with hearing loss.[11] Speech therapy may be useful and it is recommended that it be started around 9 months of age.[11] As those with Down's typically have good hand eye coordination, learning sign language may be possible.[22] Augmentative and alternative communication methods, such as pointing, body language, objects, or pictures are often used to help with communication even though there is little concrete evidence.[72] Behavioral issues and mental illness are typically managed with counselling and or medications.[10]

Education programs before reaching school age may be useful.[2] School-age children with Down syndrome may benefit from inclusive education (whereby students of differing abilities are placed in classes with their peers of the same age) provided that some adjustments are made to the curriculum.[73] Evidence to support this however is not very strong.[74] In the United States the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1975 requires that public schools generally allow attendance by students with Down's.[75]

Other

Tympanostomy tube are often needed[11] and often more than one set during the person's childhood.[30] A tonsillectomy is also often done to help with sleep apnea and throat infections.[11] Surgery, however, does not always address the sleep apnea and a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine may be useful.[30] Physical therapy and participation in physical education may improve motor skills.[76] Evidence to support this in adults; however, is not very good.[77]

Efforts to prevent respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) with human monoclonal antibodies should be considered, especially in those with heart problems.[2] In those who develop dementia there is no evidence for memantine,[78] donepezil,[79] rivastigmine,[80] or galantamine.[81]

Plastic surgery has been suggested as a method of improving the appearance and thus the acceptance of people with Down's.[82] It has also been proposed as a way to improve speech.[82] Evidence, however, does not support a meaningful difference in either of these outcomes.[82] Plastic surgery on children with Down syndrome is uncommon,[83] and continues to be controversial.[82] The U.S. National Down Syndrome Society views the goal as one of mutual respect and acceptance not appearance.[83]

Many alternative medical techniques are used in Down syndrome; however, they are poorly supported by evidence.[82] These include: dietary changes, message, animal therapy, chiropractics and naturopathy among others.[82] Some proposed treatments may also be harmful.[42]

Prognosis

Between 5 and 15% of children with Down syndrome in Europe attend regular school.[84] Some graduate from high school; however, most do not.[8] Of those with intellectual disabilities in the United States who attended high school about 40% graduated.[85] Many learn to read and write and some are able to do paid work.[8] In adulthood about 20% in the United States do paid work in some capacity.[9][86] In Europe, however, less than 1% have regular jobs.[84] Many are able to live semi-independently,[14] but they often require help with financial, medical, and legal matters.[10] Those with mosaic Down syndrome usually have better outcomes.[42]

Individuals with Down syndrome have a higher risk of death than the general population.[11] This is most often from heart problems or infections.[2][3] Following improved medical care, particularly for heart and gastrointestinal problems, the life expectancy has increased.[2] This increase has been from 12 years in 1912,[87] to 25 years in the 1980s,[2] to 50 to 60 years in the developed world in the 2000s.[3][10] Currently between 4 and 12% die in the first year of life.[38] The probability of long-term survival is partly determined by the presence of heart problems. In those with congenital heart problems 60% survive to 10 years and 50% survive to 30 years of age.[14] In those without heart problems 85% survive to 10 years and 80% survive to 30 years of age.[14] About 10% live to 70 years of age.[43]

Epidemiology

Globally, as of 2010, Down syndrome occurs in about 1 per 1000 births[2] and results in about 17,000 deaths.[89] It occurs more commonly in countries where abortion is not allowed and in countries where pregnancy more commonly occurs at a later age.[2] About 1.4 per 1000 live birth in the United States[90] and 1.1 per 1000 live births in Norway are affected.[3] In the 1950s, in the United States, it occurred in 2 per 1000 live births with the decrease since then due to prenatal screening and abortions.[52] The number of pregnancies with Down syndrome is more than two times greater with many spontaneously aborting.[10] It is the cause of 8% of all congenital disorders.[2]

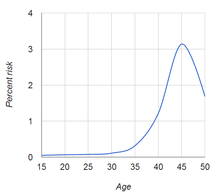

Maternal age affects the chances having a pregnancy with Down syndrome.[88] At age 20 the chance 1 in 1441; at age 30 it is 1 in 959; at age 40 it is 1 in 84; and at age 50 it is 1 in 44.[88] Although the probability increases with maternal age, 70% of children with Down syndrome are born to women 35 years of age and younger, reflecting the fact that younger people have more children.[88] An older age of the father is also a risk factor in women older than 35 but not women younger than 35 and may partly explain the increase in risk as women age.[91]

History

English physician John Langdon Down first characterized Down syndrome as a separate form of mental disability in 1862, and in a more widely published report in 1866.[11][93][94] Édouard Séguin described it as separate from cretinism in 1944.[12][95] By the 20th century, Down syndrome had become the most recognizable form of mental disability.

In Ancient times many infants with disabilities were either killed or abandoned.[12] A number of historical pieces of art are believed to portray Down syndrome including pottery from AD 500 from South America and the 16th century painting "The Adoration of the Christ Child".[12]

In the 20th century many individuals with Down syndrome were institutionalized, few of the associated medical problems were treated, and most died in infancy or early adult life. With the rise of the eugenics movement, 33 of the then 48 U.S. states and several countries began programs of forced sterilization of individuals with Down syndrome and comparable degrees of disability. Action T4 in Nazi Germany made public policy of a program of systematic involuntary euthanization.[96]

With the discovery of karyotype techniques in the 1950s, it became possible to identify abnormalities of chromosomal number or shape.[95] In 1959, Jérôme Lejeune reported the discovery that Down syndrome resulted from an extra chromosome.[11] However this claim has been disputed,[97] and in 2014 the Scientific Council of the French Federation of Human Genetics unanimously awarded its Grand Prize to his colleague Marthe Gautier for this discovery.[98] As a result of this discovery, the condition became known as trisomy 21.[99] Even before the discovery of its cause, the presence of the syndrome in all races, its association with older maternal age, and its rarity of recurrence had been noticed. Medical texts had assumed it was caused by a combination of inheritable factors that had not been identified. Other theories had focused on injuries sustained during birth.[100]

Society and culture

Name

Due to his perception that children with Down syndrome shared facial similarities with those of Blumenbach's Mongolian race, Down used the term mongoloid.[43][101] While the term "mongoloid" (also "mongolism" or "mongolian imbecility") continued to be used until the early 1970s, it is now considered unacceptable and is no longer in common use.[102] In 1961, 19 scientists suggested that "mongolism" had "misleading connotations" and had become "an embarrassing term".[102][103] The World Health Organization (WHO) dropped the term in 1965 after a request by the Mongolian delegate.[102]

In 1975, the United States National Institutes of Health convened a conference to standardize the naming and recommended eliminating the possessive form.[104] Although both the possessive and non-possessive forms are used by the general population.[105] The term "trisomy 21" is also used frequently.[103][106]

Ethics

Some argue that it is unethical not to offer screening for Down syndrome.[107] As it is a medically reasonable procedure, per informed consent, people should at least be given information about it.[107] It will then be the mother's choice, based on her personal belief, regarding how much or how little screening she wishes.[108][109] When results from testing are back, it is also considered unethical not to give the results to the person in question.[107][110]

Some deem it reasonable for parents to select a child who would have the highest well-being.[111] One criticism of this is that it often values those with disabilities less.[112] The disability rights movement does not have a position on screening.[113] Some members though consider testing and abortion discriminatory.[113] Some in the United States who are pro-life are okay with abortion if the fetus is disabled while others are not.[114] Of a group of 40 mothers in the United States who have had one child with Down syndrome, half agreed to screening in the next pregnancy.[114]

Within Christianity, Protestants often see abortion as acceptable when a fetus has Down syndrome.[115] Orthodox Christians and Roman Catholics often do not see it as acceptable.[115] Some of those against screening refer to it as a form of "eugenics".[115] There is disagreement within Islam regarding the acceptability of abortion in those who have a pregnancy with Down syndrome.[116] Some Islamic countries allow abortion while others do not.[116] Women may face stigmatization which ever decision she makes.[117]

Advocacy groups

Advocacy groups for Down syndrome formed after the Second World War.[118] These were organizations advocating for the inclusion of people with Down Syndrome into the general school system and for a greater understanding of the condition among the general population,[118] as well as groups providing support for families with children with Down syndrome.[118] Organizations included: Royal Society for Handicapped Children and Adults (MENCAP) founded in the UK in 1946 by Judy Fryd,[118][119] Kobato Kai founded in Japan in 1964,[118] the National Down Syndrome Congress founded in the United States in 1973 by Kathryn McGee and others,[118][120] and the National Down Syndrome Society founded in 1979 in the United States.[118]

The first World Down Syndrome Day was held on 21 March 2006.[121] The day and month were chosen to correspond with 21 and trisomy respectively.[122] It was recognized by the United Nations General Assembly in 2011.[121]

Research

There are efforts to develop treatment to improve intelligence in those with Down's.[123] One hope is to use stem cells.[124]

References

- ^ a b c Patterson, D (Jul 2009). "Molecular genetic analysis of Down syndrome". Human genetics. 126 (1): 195–214. PMID 19526251.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Weijerman, ME (Dec 2010). "Clinical practice. The care of children with Down syndrome". European journal of pediatrics. 169 (12): 1445–52. doi:10.1007/s00431-010-1253-0. PMID 20632187.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Malt, EA (Feb 5, 2013). "Health and disease in adults with Down syndrome". Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening : tidsskrift for praktisk medicin, ny raekke. 133 (3): 290–4. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.12.0390. PMID 23381164.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Natoli, JL (Feb 2012). "Prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome: a systematic review of termination rates (1995–2011)". Prenatal diagnosis. 32 (2): 142–53. doi:10.1002/pd.2910. PMID 22418958.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Mansfield, C (Sep 1999). "Termination rates after prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome, spina bifida, anencephaly, and Turner and Klinefelter syndromes: a systematic literature review. European Concerted Action: DADA (Decision-making After the Diagnosis of a fetal Abnormality)". Prenatal diagnosis. 19 (9): 808–12. PMID 10521836.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Roizen, NJ; Patterson, D (April 2003). "Down's syndrome". Lancet. 361 (9365): 1281–89. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12987-X. PMID 12699967.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Facts About Down Syndrome". National Association for Down Syndrome. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ a b c Steinbock, Bonnie (2011). Life before birth the moral and legal status of embryos and fetuses (2nd ed. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-19-971207-6.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Szabo, Liz (May 9th 2013). "Life with Down syndrome is full of possibilities". USA Today. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Down Syndrome and Other Abnormalities of Chromosome Number". Nelson textbook of pediatrics (19th ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. 2011. pp. Chapter 76.2. ISBN 1-4377-0755-6.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Hickey, F (2012). "Medical update for children with Down syndrome for the pediatrician and family practitioner". Advances in pediatrics. 59 (1): 137–57. doi:10.1016/j.yapd.2012.04.006. PMID 22789577.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Evans-Martin, F. Fay (2009). Down syndrome. New York: Chelsea House. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4381-1950-2.

- ^ Faragher, edited by Rhonda (2013). Educating Learners with Down Syndrome Research, theory, and practice with children and adolescents. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-134-67335-3.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Hammer, edited by Stephen J. McPhee, Gary D. (2010). "Pathophysiology of Selected Genetic Diseases". Pathophysiology of disease : an introduction to clinical medicine (6th ed. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. Chapter 2. ISBN 978-0-07-162167-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sankar, editors John M. Pellock, Blaise F.D. Bourgeois, W. Edwin Dodson ; associate editors, Douglas R. Nordli, Jr., Raman (2008). Pediatric epilepsy diagnosis and therapy (3rd ed. ed.). New York: Demos Medical Pub. p. Chapter 67. ISBN 978-1-934559-86-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Epstein, Charles J. (2007). The consequences of chromosome imbalance : principles, mechanisms, and models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 255–256. ISBN 978-0-521-03809-6.

- ^ Daniel Bernstein (2012). Pediatrics for medical students (3rd ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-7817-7030-9.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Tecklin, Jan S. (2008). Pediatric physical therapy (4th ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-7817-5399-9.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d e Domino, edited by Frank J. (2007). The 5-minute clinical consult 2007 (2007 ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-7817-6334-9.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Wilson, Golder N. (2006). Preventive management of children with congenital anomalies and syndromes (2 ed. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-521-61734-5.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Williams Textbook of Endocrinology Expert Consult (12th ed. ed.). London: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2011. ISBN 978-1-4377-3600-7.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d e Reilly, C (Oct 2012). "Behavioural phenotypes and special educational needs: is aetiology important in the classroom?". Journal of intellectual disability research : JIDR. 56 (10): 929–46. PMID 22471356.

- ^ Batshaw, Mark, ed. (2005). Children with disabilities (5th ed.). Baltimore [u.a.]: Paul H. Brookes. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-55766-581-2.

- ^ Patterson, T (Apr 2013). "Systematic review of cognitive development across childhood in Down syndrome: implications for treatment interventions". Journal of intellectual disability research : JIDR. 57 (4): 306–18. PMID 23506141.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rondal, edited by Jean-Adolphe (2007). Therapies and rehabilitation in Down syndrome. Chichester, England: J. Wiley & Sons. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-470-31997-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kent, RD (Feb 2013). "Speech impairment in Down syndrome: a review". Journal of speech, language, and hearing research : JSLHR. 56 (1): 178–210. PMID 23275397.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McGuire, Dennis and Chicoine, Brian (2006). Mental Wellness in Adults with Down Syndrome. Bethesday, MD: Woodbine House, Inc. p. 49. ISBN 1-890627-65-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Margulies, Phillip (2007). Down syndrome (1st ed. ed.). New York: Rosen Pub. Group. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4042-0695-3.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ M. William Schwartz, ed. (2012). The 5-minute pediatric consult (6th ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-4511-1656-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c Rodman, R (Jun 2012). "The otolaryngologist's approach to the patient with Down syndrome". Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 45 (3): 599–629, vii–viii. PMID 22588039.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Evans-Martin, F. Fay (2009). Down syndrome. New York: Chelsea House. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-4381-1950-2.

- ^ a b c d Tintinalli, Judith E. (2010). "The Child with Special Health Care Needs". Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Emergency Medicine (Tintinalli)). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. pp. Chapter 138. ISBN 0-07-148480-9.

- ^ a b Sam Goldstein, ed. (2011). Handbook of neurodevelopmental and genetic disorders in children (2nd ed. ed.). New York: Guilford Press. p. 365. ISBN 978-1-60623-990-2.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ editor, Vee P. Prasher, (2009). Neuropsychological assessments of dementia in Down syndrome and intellectual disabilities. London: Springer. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-84800-249-4.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Richard Urbano (9 September 2010). Health Issues Among Persons With Down Syndrome. Academic Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-12-374477-7.

- ^ Andrei Thomas-Tikhonenko, ed. (2010). Cancer genome and tumor microenvironment (Online-Ausg. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-4419-0711-0.

- ^ a b Seewald, L (Sep 2012). "Acute leukemias in children with Down syndrome". Molecular genetics and metabolism. 107 (1–2): 25–30. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.07.011. PMID 22867885.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Gamis, AS (Nov 2012). "Transient myeloproliferative disorder in children with Down syndrome: clarity to this enigmatic disorder". British journal of haematology. 159 (3): 277–87. PMID 22966823.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Graber, E (Dec 2012). "Down syndrome and thyroid function". Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America. 41 (4): 735–45. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2012.08.008. PMID 23099267.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Moore, SW (Aug 2008). "Down syndrome and the enteric nervous system". Pediatric surgery international. 24 (8): 873–83. PMID 18633623.

- ^ a b c d Pradhan, M; Dalal, A; Khan, F; Agrawal, S (2006). "Fertility in men with Down syndrome: a case report". Fertil Steril. 86 (6): 1765.e1–3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.03.071. PMID 17094988.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Nelson, Maureen R. (2011). Pediatrics. New York: Demos Medical. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-61705-004-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Howard Reisner (2013). Essentials of Rubin's Pathology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 129–131. ISBN 978-1-4511-8132-6.

- ^ a b c Lana-Elola, E (Sep 2011). "Down syndrome: searching for the genetic culprits". Disease models & mechanisms. 4 (5): 586–95. PMID 21878459.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "CDC—Birth Defects, Down Syndrome—NCBDDD". Cdc.gov. 2013-11-06.

- ^ Kausik Mandal (2013). Treatment & prognosis in pediatrics. Jaypee Brothers Medical P. p. 391. ISBN 978-93-5090-428-2.

- ^ Fletcher-Janzen, edited by Cecil R. Reynolds, Elaine (2007). Encyclopedia of special education a reference for the education of children, adolescents, and adults with disabilities and other exceptional individuals (3rd ed. ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 458. ISBN 978-0-470-17419-7.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhang, edited by Liang Cheng, David Y. (2008). Molecular genetic pathology. Totowa, N.J.: Humana. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-59745-405-6.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b A.K. David (2013). Family Medicine Principles and Practice (Sixth Edition ed.). New York, NY: Springer New York. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-387-21744-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d e Michael Cummings (2013). Human Heredity: Principles and Issues (10 ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-285-52847-2.

- ^ Jerome Frank Strauss, Robert L. Barbieri (2009). Yen and Jaffe's reproductive endocrinology : physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical management (6th ed. ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 791. ISBN 978-1-4160-4907-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c Menkes, John H. (2005). Child neurology (7th ed. ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-7817-5104-9.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Shaffer, R.J. McKinlay Gardner, Grant R. Sutherland, Lisa G. (2012). Chromosome abnormalities and genetic counseling (4th ed. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-19-974915-7.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Genetics of Down Syndrome". Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ Michael H. Ebert, ed. (2008). "Psychiatric Genetics". Current diagnosis & treatment psychiatry (2nd ed. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. Chapter 3. ISBN 0-07-142292-7.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Weksler, ME (Apr 2013). "Alzheimer's disease and Down's syndrome: treating two paths to dementia". Autoimmunity reviews. 12 (6): 670–3. PMID 23201920.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e ACOG Committee on Practice, Bulletins (Jan 2007). "ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 77: screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities". Obstetrics and gynecology. 109 (1): 217–27. PMID 17197615.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2008). "CG62: Antenatal care". London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Canick, J (Jun 2012). "Prenatal screening for trisomy 21: recent advances and guidelines". Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine : CCLM / FESCC. 50 (6): 1003–8. PMID 21790505.

- ^ Noninvasive Prenatal Diagnosis of Fetal Aneuploidy Using Cell-Free Fetal Nucleic Acids in Maternal Blood: Clinical Policy (Effective 05/01/2013) from Oxford Health Plans

- ^ Mersy, E (2013 Jul-Aug). "Noninvasive detection of fetal trisomy 21: systematic review and report of quality and outcomes of diagnostic accuracy studies performed between 1997 and 2012". Human reproduction update. 19 (4): 318–29. PMID 23396607.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bianchi, DW (2014 Feb 27). "DNA sequencing versus standard prenatal aneuploidy screening". The New England journal of medicine. 370 (9): 799–808. PMID 24571752.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Agathokleous, M (Mar 2013). "Meta-analysis of second-trimester markers for trisomy 21". Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 41 (3): 247–61. doi:10.1002/uog.12364. PMID 23208748.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Malone, FD (Nov 2003). "First-trimester sonographic screening for Down syndrome". Obstetrics and gynecology. 102 (5 Pt 1): 1066–79. PMID 14672489.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Alldred, SK (Jun 13, 2012). "Second trimester serum tests for Down's Syndrome screening". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 6: CD009925. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009925. PMID 22696388.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Verweij, EJ (2012). "Diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive detection of fetal trisomy 21 in maternal blood: a systematic review". Fetal diagnosis and therapy. 31 (2): 81–6. doi:10.1159/000333060. PMID 22094923.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mersy, E (Jul–Aug 2013). "Noninvasive detection of fetal trisomy 21: systematic review and report of quality and outcomes of diagnostic accuracy studies performed between 1997 and 2012". Human reproduction update. 19 (4): 318–29. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt001. PMID 23396607.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Benn, P (Jan 2012). "Prenatal Detection of Down Syndrome using Massively Parallel Sequencing (MPS): a rapid response statement from a committee on behalf of the Board of the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis, 24 October 2011" (PDF). Prenatal diagnosis. 32 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1002/pd.2919. PMID 22275335.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Tabor, A (2010). "Update on procedure-related risks for prenatal diagnosis techniques". Fetal diagnosis and therapy. 27 (1): 1–7. PMID 20051662.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Choi, H (Mar–Apr 2012). "Decision making following a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome: an integrative review". Journal of midwifery & women's health. 57 (2): 156–64. doi:10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00109.x. PMID 22432488.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Bull, MJ (Aug 2011). "Health supervision for children with Down syndrome". Pediatrics. 128 (2): 393–406. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1605. PMID 21788214.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Roberts, JE; Price, J; Malkin, C (2007). "Language and communication development in Down syndrome". Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 13 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20136. PMID 17326116.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Inclusion: Educating Students with Down Syndrome with Their Non-Disabled Peers" (PDF). National Down Syndrome Society. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ Lindsay, G (Mar 2007). "Educational psychology and the effectiveness of inclusive education/mainstreaming". The British journal of educational psychology. 77 (Pt 1): 1–24. PMID 17411485.

- ^ New, Rebecca S. (2007). Early childhood education an international encyclopedia. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-313-01448-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wearmouth, Janice (2012). Special educational needs, the basics. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-136-57989-9.

- ^ Andriolo, RB (May 12, 2010). "Aerobic exercise training programmes for improving physical and psychosocial health in adults with Down syndrome". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (5): CD005176. PMID 20464738.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mohan, M (Jan 21, 2009). "Memantine for dementia in people with Down syndrome". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (1): CD007657. PMID 19160343.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mohan, M (Jan 21, 2009). "Donepezil for dementia in people with Down syndrome". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (1): CD007178. PMID 19160328.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mohan, M (Jan 21, 2009). "Rivastigmine for dementia in people with Down syndrome". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (1): CD007658. PMID 19160344.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mohan, M (Jan 21, 2009). "Galantamine for dementia in people with Down syndrome". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (1): CD007656. PMID 19160342.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Roizen, NJ (2005). "Complementary and alternative therapies for Down syndrome". Mental retardation and developmental disabilities research reviews. 11 (2): 149–55. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20063. PMID 15977315.

- ^ a b National Down Syndrome Society. "Position Statement on Cosmetic Surgery for Children with Down Syndrome". Archived from the original on 2006-09-06. Retrieved 2006-06-02.

- ^ a b "European Down Syndrome Association news" (PDF). European Down Syndrome Association. 2006. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "Number of 14- through 21-year-old students served under Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Part B, who exited school, by exit reason, age, and type of disability: 2007-08 and 2008-09". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "Down's Syndrome: Employment Barriers". Rehab Care International. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Richard Urbano (9 September 2010). Health Issues Among Persons With Down Syndrome. Academic Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-12-374477-7.

- ^ a b c d Morris, JK (2002). "Revised estimates of the maternal age specific live birth prevalence of Down's syndrome". Journal of medical screening. 9 (1): 2–6. PMID 11943789.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lozano, R (Dec 15, 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

- ^ Parker, SE (Dec 2010). "Updated National Birth Prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006". Birth defects research. Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology. 88 (12): 1008–16. doi:10.1002/bdra.20735. PMID 20878909.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Douglas T. Carrell, ed. (2013). Paternal influences on human reproductive success. Cambridge University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-107-02448-9.

- ^ Levitas, AS (Feb 1, 2003). "An angel with Down syndrome in a sixteenth century Flemish Nativity painting". American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 116A (4): 399–405. PMID 12522800.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Down, JLH (1866). "Observations on an ethnic classification of idiots". Clinical Lecture Reports, London Hospital. 3: 259–62. Retrieved 2006-07-14.

- ^ Conor, WO (1998). John Langdon Down, 1828–1896. Royal Society of Medicine Press. ISBN 1-85315-374-5.

- ^ a b Neri, G (Dec 2009). "Down syndrome: comments and reflections on the 50th anniversary of Lejeune's discovery". American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 149A (12): 2647–54. PMID 19921741.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ David Wright (25 August 2011). Downs:The history of a disability: The history of a disability. Oxford University Press. pp. 104–108. ISBN 978-0-19-956793-5. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ David Wright (25 August 2011). Downs:The history of a disability: The history of a disability. Oxford University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-19-956793-5. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Trisomie : une pionnière intimidée

- ^ David Wright (25 August 2011). Downs:The history of a disability: The history of a disability. Oxford University Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-19-956793-5. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Warkany, J (1971). Congenital Malformations. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers, Inc. pp. 313–14. ISBN 0-8151-9098-0.

- ^ Ward, OC (Aug 1999). "John Langdon Down: the man and the message". Down's syndrome, research and practice : the journal of the Sarah Duffen Centre / University of Portsmouth. 6 (1): 19–24. PMID 10890244.

- ^ a b c Howard-Jones, Norman (1979). "On the diagnostic term "Down's disease"". Medical History. 23 (1): 102–04. PMC 1082401. PMID 153994.

- ^ a b Rodríguez-Hernández, ML (Jul 30, 2011). "Fifty years of evolution of the term Down's syndrome". Lancet. 378 (9789): 402. PMID 21803206.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Classification and nomenclature of morphological defects (Discussion)". The Lancet. 305 (7905): 513. 1975. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(75)92847-0. PMID 46972.

- ^ Smith, Kieron (2011). The politics of down syndrome. [New Alresford, Hampshire]: Zero. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-84694-613-4.

- ^ Westman, Judith A. (2005). Medical genetics for the modern clinician. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-7817-5760-7.

- ^ a b c Chervenak, FA (Apr 2010). "Ethical considerations in first-trimester Down syndrome risk assessment". Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 22 (2): 135–8. PMID 20125014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Chervenak, FA (Jul 2008). "Enhancing patient autonomy with risk assessment and invasive diagnosis: an ethical solution to a clinical challenge". American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 199 (1): 19.e1-4. PMID 18355783.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zindler, L (Apr–Jun 2005). "Ethical decision making in first trimester pregnancy screening". The Journal of perinatal & neonatal nursing. 19 (2): 122–31, quiz 132–3. PMID 15923961.

- ^ Sharma, G (Feb 15, 2007). "Ethical considerations of early (first vs. second trimester) risk assessment disclosure for trisomy 21 and patient choice in screening versus diagnostic testing". American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 145C (1): 99–104. PMID 17299736.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Savulescu, J (Jun 2009). "The moral obligation to create children with the best chance of the best life". Bioethics. 23 (5): 274–90. PMID 19076124.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bennett, R (Jun 2009). "The fallacy of the Principle of Procreative Beneficence". Bioethics. 23 (5): 265–73. PMID 18477055.

- ^ a b Parens, E (2003). "Disability rights critique of prenatal genetic testing: reflections and recommendations". Mental retardation and developmental disabilities research reviews. 9 (1): 40–7. PMID 12587137.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Green, RM (Spring 1997). "Parental autonomy and the obligation not to harm one's child genetically". The Journal of law, medicine & ethics : a journal of the American Society of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 25 (1): 5–15, 2. PMID 11066476.

- ^ a b c Bill J Leonard, Jill Y. Crainshaw (2013). Encyclopedia of religious controversies in the United States (2nd ed. ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 278. ISBN 978-1-59884-867-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Al-Alaiyan, S (Jan 2012). "Aborting a Malformed Fetus: A Debatable Issue in Saudi Arabia". Journal of clinical neonatology. 1 (1): 6–11. PMID 24027674.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sara Grace Shields, Lucy M. Candib (2010). Woman-centered care in pregnancy and childbirth. Oxford: Radcliffe Pub. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-84619-161-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g David Wright (2011). Downs: The history of a disability. Oxford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-19-161978-6.

- ^ "Timeline". MENCAP. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ "National Down Syndrome Organizations in the U.S." Global Down Syndrome Foundation. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ a b "World Down Syndrome Day". Down Syndrome International. Down Syndrome International. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Pratt, Geraldine (2012). The global and the intimate feminism in our time. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-231-52084-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Goodman, MJ (Apr 2013). "New therapies for treating Down syndrome require quality of life measurement". American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 161A (4): 639–41. PMID 23495233.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Briggs, JA (Mar 2013). "Concise review: new paradigms for Down syndrome research using induced pluripotent stem cells: tackling complex human genetic disease". Stem cells translational medicine. 2 (3): 175–84. PMID 23413375.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)