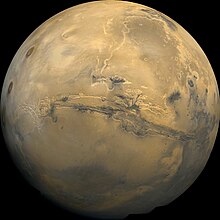

Colonization of Mars

The colonization of Mars refers to the concept of humans setting out to live permanently on Mars. Originally a science fiction idea, it is now the subject of serious feasibility studies.

Relative similarity to Earth

Earth is similar to its "sister planet" Venus in bulk composition, size and surface gravity, but Mars's similarities to Earth are more compelling when considering colonization. These include:

- The Martian day (or sol) is very close in duration to Earth's. A solar day on Mars is 24 hours 39 minutes 35.244 seconds. (See Timekeeping on Mars.)

- Mars has a surface area that is 28.4% of Earth's, only slightly less than the amount of dry land on Earth (which is 29.2% of Earth's surface). Mars has half the radius of Earth and only one-tenth the mass. This means that it has a smaller volume (~15%) and lower average density than Earth.

- Mars has an axial tilt of 25.19°, similar to Earth's 23.44°. As a result, Mars has seasons much like Earth, though they last nearly twice as long because the Martian year is about 1.88 Earth years. The Martian north pole currently points at Cygnus, not Ursa Minor like Earth's.

- Recent observations by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, ESA's Mars Express and NASA's Phoenix Lander confirm the presence of water ice on Mars.

Differences from Earth

- While there are some extremophile organisms that survive in hostile conditions on Earth, including simulations that approximate Mars, plants and animals generally cannot survive the ambient conditions present on the surface of Mars.[1]

- The surface gravity of Mars is 38% that of Earth. Although microgravity is known to cause health problems such as muscle loss and bone demineralization,[2][3] it is not known if Martian gravity would have a similar effect. The Mars Gravity Biosatellite was a proposed project designed to learn more about what effect Mars's lower surface gravity would have on humans.[4]

- Mars is much colder than Earth, with a mean surface temperature between 186 and 268 K (−87 °C and −5 °C).[5][6] The lowest temperature ever recorded on Earth was −93.2 °C, in Antarctica.

- Surface water on Mars may occur transiently, but only under certain conditions.[7][8]

- Because Mars is farther from the Sun, the amount of solar energy entering the upper atmosphere per unit area (the solar constant) is less than half of that entering Earth's upper atmosphere. However, due to the thinner atmosphere, more solar energy reaches the surface.

- Mars's orbit is more eccentric than Earth's, increasing temperature and solar constant variations.

- Due to the relative lack of a magnetosphere, in combination with a thin atmosphere—less than 1% that of Earth's—Mars has extreme amounts of ultraviolet radiation that would pose an ongoing and serious threat.

- The atmospheric pressure on Mars is far below the Armstrong limit at which people can survive without pressure suits. Since terraforming cannot be expected as a near-term solution, habitable structures on Mars would need to be constructed with pressure vessels similar to spacecraft, capable of containing a pressure between 300 and 1000 mbar.

- The Martian atmosphere is 95% carbon dioxide, 3% nitrogen, 1.6% argon, and traces of other gases including oxygen totaling less than 0.4%.

- Martian air has a partial pressure of CO2 of 7.1 mbar, compared to .31 mbar on Earth. CO2 poisoning (hypercapnia) in humans begins at about 1 mbar. Even for plants, CO2 much above 1.5 mbar is toxic. This means Martian air is completely toxic to both plants and animals even at the reduced total pressure .[9]

| Location | Pressure |

|---|---|

| Olympus Mons summit | 0.03 kilopascals (0.0044 psi) |

| Mars average | 0.6 kilopascals (0.087 psi) |

| Hellas Planitia bottom | 1.16 kilopascals (0.168 psi) |

| Armstrong limit | 6.25 kilopascals (0.906 psi) |

| Mount Everest summit[10] | 33.7 kilopascals (4.89 psi) |

| Earth sea level | 101.3 kilopascals (14.69 psi) |

Conditions for human habitation

Conditions on the surface of Mars are closer to the conditions on Earth in terms of temperature, atmospheric pressure than on any other planet or moon, except for the cloud tops of Venus,[11] but are not hospitable to humans or most known life forms due to greatly reduced air pressure, an atmosphere with only 0.1% oxygen, and the lack of liquid water (although large amounts of frozen water have been detected).

In 2012, it was reported that some lichen and cyanobacteria survived and showed remarkable adaptation capacity for photosynthesis after 34 days in simulated Martian conditions in the Mars Simulation Laboratory (MSL) maintained by the German Aerospace Center (DLR).[12][13][14]

Humans have explored parts of Earth that match some conditions on Mars. Based on NASA rover data, temperatures on Mars (at low latitudes) are similar to those in Antarctica.[15] The atmospheric pressure at the highest altitudes reached by manned balloon ascents (35 km (114,000 feet) in 1961,[16] 38 km in 2012) is similar to that on the surface of Mars.[17]

Human survival on Mars would require complex life support measures and living in artificial environments.

Terraforming

It may eventually be possible to terraform Mars to allow a wide variety of life forms, including humans, to survive unaided on Mars's surface.[18]

Radiation

Mars has no global magnetic field comparable to Earth's geomagnetic field. Combined with a thin atmosphere, this permits a significant amount of ionizing radiation to reach the Martian surface. The Mars Odyssey spacecraft carried an instrument, the Mars Radiation Environment Experiment (MARIE), to measure the dangers to humans. MARIE found that radiation levels in orbit above Mars are 2.5 times higher than at the International Space Station. Average doses were about 22 millirads per day (220 micrograys per day or 0.08 gray per year.)[19] A three-year exposure to such levels would be close to the safety limits currently adopted by NASA.[citation needed] Levels at the Martian surface would be somewhat lower and might vary significantly at different locations depending on altitude and local magnetic fields. Building living quarters underground (possibly in lava tubes that are already present) would significantly lower the colonists' exposure to radiation. Occasional solar proton events (SPEs) produce much higher doses.

Much remains to be learned about space radiation. In 2003, NASA's Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center opened a facility, the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory, at Brookhaven National Laboratory, that employs particle accelerators to simulate space radiation. The facility studies its effects on living organisms along with shielding techniques.[20] Initially, there was some evidence that this kind of low level, chronic radiation is not quite as dangerous as once thought; and that radiation hormesis occurs.[21] However, results from a 2006 study indicated that protons from cosmic radiation may cause twice as much serious damage to DNA as previously expected, exposing astronauts to greater risk of cancer and other diseases.[22] As a result of the higher radiation in the Martian environment, the summary report of the Review of U.S. Human Space Flight Plans Committee released in 2009 reported that "Mars is not an easy place to visit with existing technology and without a substantial investment of resources."[22] NASA is exploring a variety of alternative techniques and technologies such as deflector shields of plasma to protect astronauts and spacecraft from radiation.[22]

Transportation

Interplanetary spaceflight

Mars requires less energy per unit mass (delta V) to reach from Earth than any planet except Venus. Using a Hohmann transfer orbit, a trip to Mars requires approximately nine months in space.[23] Modified transfer trajectories that cut the travel time down to seven or six months in space are possible with incrementally higher amounts of energy and fuel compared to a Hohmann transfer orbit, and are in standard use for robotic Mars missions. Shortening the travel time below about six months requires higher delta-v and an exponentially increasing amount of fuel, and is not feasible with chemical rockets, but might be feasible with advanced spacecraft propulsion technologies, some of which have already been tested, such as VASIMR,[24] and nuclear rockets. In the former case, a trip time of forty days could be attainable,[25] and in the latter, a trip time down to about two weeks.[26]

During the journey the astronauts are subject to radiation, which requires a means to protect them. Cosmic radiation and solar wind cause DNA damage, which increases the risk of cancer significantly. The effect of long term travel in interplanetary space is unknown, but scientists estimate an added risk of between 1% and 19%, most likely 3.4%, for men to die of cancer because of the radiation during the journey to Mars and back to Earth. For women the probability is higher due to their larger glandular tissues.[27]

Landing on Mars

Mars has a gravity 0.38 times that of Earth and the density of its atmosphere is 1% of that on Earth.[28] The relatively strong gravity and the presence of aerodynamic effects makes it difficult to land heavy, crewed spacecraft with thrusters only, as was done with the Apollo moon landings, yet the atmosphere is too thin for aerodynamic effects to be of much help in braking and landing a large vehicle. Landing piloted missions on Mars will require braking and landing systems different from anything used to land crewed spacecraft on the Moon or robotic missions on Mars.[29]

If one assumes carbon nanotube construction material will be available with a strength of 130 GPa then a space elevator could be built to land people and material on Mars.[30] A space elevator on Phobos has also been proposed.[31]

Equipment needed for colonization

Colonization of Mars will require a wide variety of equipment—both equipment to directly provide services to humans as well as production equipment used to produce food, propellant, water, energy and breathable oxygen—in order to support human colonization efforts. Required equipment will include:[26]

- habitats

- storage facilities

- shop workspaces

- resource extraction equipment—initially for water and oxygen, later for a wider cross section of minerals, building materials, etc.

- energy production and storage equipment, some solar and perhaps other forms as well

- food production spaces and equipment

- propellant production equipment, generally thought to be hydrogen and methane[32] for fuel—with oxygen oxidizer—for chemical rocket engines

- communication equipment

Communication

Communications with Earth are relatively straightforward during the half-sol when Earth is above the Martian horizon. NASA and ESA included communications relay equipment in several of the Mars orbiters, so Mars already has communications satellites. While these will eventually wear out, additional orbiters with communication relay capability are likely to be launched before any colonization expeditions are mounted.

The one-way communication delay due to the speed of light ranges from about 3 minutes at closest approach (approximated by perihelion of Mars minus aphelion of Earth) to 22 minutes at the largest possible superior conjunction (approximated by aphelion of Mars plus aphelion of Earth). Real-time communication, such as telephone conversations or Internet Relay Chat, between Earth and Mars would be highly impractical due to the long time lags involved. NASA has found that direct communication can be blocked for about two weeks every synodic period, around the time of superior conjunction when the Sun is directly between Mars and Earth,[33] although the actual duration of the communications blackout varies from mission to mission depending on various factors - such as the amount of link margin designed into the communications system, and the minimum data rate that is acceptable from a mission standpoint. In reality most missions at Mars have had communications blackout periods of the order of a month.[34]

A satellite at the L4 or L5 Earth–Sun Lagrangian point could serve as a relay during this period to solve the problem; even a constellation of communications satellites would be a minor expense in the context of a full colonization program. However, the size and power of the equipment needed for these distances make the L4 and L5 locations unrealistic for relay stations, and the inherent stability of these regions, although beneficial in terms of station-keeping, also attracts dust and asteroids, which could pose a risk.[35] Despite that concern, the STEREO probes passed through the L4 and L5 regions without damage in late 2009.

Recent work by the University of Strathclyde's Advanced Space Concepts Laboratory, in collaboration with the European Space Agency, has suggested an alternative relay architecture based on highly non-Keplerian orbits. These are a special kind of orbit produced when continuous low-thrust propulsion, such as that produced from an ion engine or solar sail, modifies the natural trajectory of a spacecraft. Such an orbit would enable continuous communications during solar conjunction by allowing a relay spacecraft to "hover" above Mars, out of the orbital plane of the two planets.[36] Such a relay avoids the problems of satellites stationed at either L4 or L5 by being significantly closer to the surface of Mars while still maintaining continuous communication between the two planets.

Robotic precursors

The path to a human colony could be prepared by robotic systems such as the Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit, Opportunity and Curiosity. These systems could help locate resources, such as ground water or ice, that would help a colony grow and thrive. The lifetimes of these systems would be measured in years and even decades, and as recent developments in commercial spaceflight have shown, it may be that these systems will involve private as well as government ownership. These robotic systems also have a reduced cost compared with early crewed operations, and have less political risk.

Wired systems might lay the groundwork for early crewed landings and bases, by producing various consumables including fuel, oxidizers, water, and construction materials. Establishing power, communications, shelter, heating, and manufacturing basics can begin with robotic systems, if only as a prelude to crewed operations.

Mars Surveyor 2001 Lander MIP (Mars ISPP Precursor) was to demonstrate manufacture of oxygen from the atmosphere of Mars,[37] and test solar cell technologies and methods of mitigating the effect of Martian dust on the power systems.[38]

Early human missions

In 1948, Wernher von Braun described in his book The Mars Project that a fleet of 10 spaceships could be built using 1000 three-stage rockets. These could bring a population of 70 people to Mars.

All of the early human missions to Mars as conceived by national governmental space programs—such as those being tentatively planned by NASA, FKA and ESA—would not be direct precursors to colonization. They are intended solely as exploration missions, as the Apollo missions to the Moon were not planned to be sites of a permanent base.

Colonization requires the establishment of permanent bases that have potential for self-expansion. A famous proposal for building such bases is the Mars Direct and the Semi-Direct plans, advocated by Robert Zubrin.[26]

Other proposals that envision the creation of a settlement have come from Jim McLane and Bas Lansdorp (the man behind Mars One, which envisions no planned return flight for the humans embarking on the journey),[39] as well as from Elon Musk whose SpaceX company, as of 2013[update], is funding development work on a space transportation system called the Mars Colonial Transporter.[40][41]

The Mars Society has established the Mars Analogue Research Station Programme at sites Devon Island in Canada and in Utah, United States, to experiment with different plans for human operations on Mars, based on Mars Direct. Modern Martian architecture concepts often include facilities to produce oxygen and propellant on the surface of the planet.

Economics

As with early colonies in the New World, economics would be a crucial aspect to a colony's success. The reduced gravity well of Mars and its position in the Solar System may facilitate Mars-Earth trade and may provide an economic rationale for continued settlement of the planet. Given its size and resources, this might eventually be a place to grow food and produce equipment that would be used by miners in the asteroid belt.

A major economic problem is the enormous up-front investment required to establish the colony and perhaps also terraform the planet.

Some early Mars colonies might specialize in developing local resources for Martian consumption, such as water and/or ice. Local resources can also be used in infrastructure construction.[42] One source of Martian ore currently known to be available is reduced iron in the form of nickel–iron meteorites. Iron in this form is more easily extracted than from the iron oxides that cover the planet.

Another main inter-Martian trade good during early colonization could be manure.[43] Assuming that life doesn't exist on Mars, the soil is going to be very poor for growing plants, so manure and other fertilizers will be valued highly in any Martian civilization until the planet changes enough chemically to support growing vegetation on its own.

Solar power is a candidate for power for a Martian colony. Solar insolation (the amount of solar radiation that reaches Mars) is about 42% of that on Earth, since Mars is about 52% farther from the Sun and insolation falls off as the square of distance. But the thin atmosphere would allow almost all of that energy to reach the surface as compared to Earth, where the atmosphere absorbs roughly a quarter of the solar radiation. Sunlight on the surface of Mars would be much like a moderately cloudy day on Earth.[44]

Nuclear power is also a good candidate, since the fuel is very dense for cheap transportation from Earth. Nuclear power also produces heat, which would be extremely valuable to a Mars colony.

Mars's reduced gravity together with its rotation rate makes it possible for the construction of a space elevator with today's materials,[citation needed] although the low orbit of Phobos could present engineering challenges. If constructed, the elevator could transport minerals and other natural resources extracted from the planet.

Economic drivers

Space colonization on Mars can roughly be said to be possible when the necessary methods of space colonization become cheap enough (such as space access by cheaper launch systems) to meet the cumulative funds that have been gathered for the purpose.

Although there are no immediate prospects for the large amounts of money required for any space colonization to be available given traditional launch costs,[45][full citation needed] there is some prospect of a radical reduction to launch costs in the 2010s, which would consequently lessen the cost of any efforts in that direction. With a published price of US$56.5 million per launch of up to 13,150 kg (28,990 lb) payload[46] to low Earth orbit, SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets are already the "cheapest in the industry".[47] Advancements currently being developed as part of the SpaceX reusable launch system development program to enable reusable Falcon 9s "could drop the price by an order of magnitude, sparking more space-based enterprise, which in turn would drop the cost of access to space still further through economies of scale."[47] SpaceX' reusable plans include Falcon Heavy and future methane-based launch vehicles including the Mars Colonial Transporter. If SpaceX is successful in developing the reusable technology, it would be expected to "have a major impact on the cost of access to space", and change the increasingly competitive market in space launch services.[48]

Alternative funding approaches might include the creation of inducement prizes. For example, the 2004 President's Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy suggested that an inducement prize contest should be established, perhaps by government, for the achievement of space colonization. One example provided was offering a prize to the first organization to place humans on the Moon and sustain them for a fixed period before they return to Earth.[49]

Possible locations for settlements

Broad regions of Mars can be considered for possible settlement sites.

Polar regions

Mars's north and south poles once attracted great interest as settlement sites because seasonally-varying polar ice caps have long been observed by telescopes from Earth. Mars Odyssey found the largest concentration of water near the north pole, but also showed that water likely exists in lower latitudes as well, making the poles less compelling as a settlement locale. Like Earth, Mars sees a midnight sun at the poles during local summer and polar night during local winter.

Equatorial regions

Mars Odyssey found what appear to be natural caves near the volcano Arsia Mons. It has been speculated that settlers could benefit from the shelter that these or similar structures could provide from radiation and micrometeoroids. Geothermal energy is also suspected in the equatorial regions.[50]

Midlands

The exploration of Mars's surface is still underway. Landers and rovers such as Phoenix, the Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity, and the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity have encountered very different soil and rock characteristics. This suggests that the Martian landscape is quite varied and the ideal location for a settlement would be better determined when more data becomes available. As on Earth, seasonal variations in climate become greater with distance from the equator.

Valles Marineris

Valles Marineris, the "Grand Canyon" of Mars, is over 3,000 km long and averages 8 km deep. Atmospheric pressure at the bottom would be some 25% higher than the surface average, 0.9 kPa vs 0.7 kPa. River channels lead to the canyon, indicating it was once flooded.

Lava tubes

Several lava tube skylights on Mars have been located.[where?] Earth based examples indicate that some should have lengthy passages offering complete protection from radiation and be relatively easy to seal using on-site materials, especially in small subsections.[51]

Advocacy

Making Mars colonization a reality is advocated by several groups with different reasons and proposals. One of the oldest is the Mars Society. They promote a NASA program to accomplish human exploration of Mars and have set up Mars analog research stations in Canada and the United States. Also are MarsDrive, which is dedicated to private initiatives for the exploration and settlement of Mars, and, Mars to Stay, which advocates recycling emergency return vehicles into permanent settlements as soon as initial explorers determine permanent habitation is possible. An initiative that went public in June 2012 is Mars One. Its aim is to establish a fully operational permanent human colony on Mars by 2023.[52]

In fiction

A few instances in fiction provide detailed descriptions of Mars colonization. They include:

- Aria by Kozue Amano

- Axis by Robert Charles Wilson

- Icehenge (1985), the Mars trilogy (Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars, 1992–1996), and The Martians (1999) by Kim Stanley Robinson

- First Landing (2002) by Robert Zubrin

- Man Plus (1976) by Frederik Pohl

- "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale" (1966), by Philip K. Dick

- Mars (1992) and Return to Mars (1999), by Ben Bova

- Climbing Olympus (1994), by Kevin J. Anderson

- Red Faction (2001), developed by Volition, published by THQ

- The Platform (2011) by James Garvey

- "The Destruction of Faena" (1974) by Alexander Kazantsev

- The Martian Chronicles (1950) by Ray Bradbury

- The Sands of Mars (1951) by Arthur C. Clarke

- Total Recall (1990) by Paul Verhoeven

- Mars Trilogy (1993–96) by Kim Stanley Robinson

See also

- Atmosphere of Mars

- Climate of Mars

- Criticism of the Space Shuttle program#Retrospect

- Effect of spaceflight on the human body

- Exploration of Mars

- Health threat from cosmic rays

- Human outpost (artificially created controlled human habitat)

- Human spaceflight

- In-situ resource utilization

- Inspiration Mars

- List of manned Mars mission plans in the 20th century

- Manned mission to Mars

- Mars analog habitat

- Mars Colonial Transporter

- Mars Direct

- MarsDrive

- Mars Desert Research Station

- Mars One

- Mars Society

- Mars to Stay

- Martian soil

- Michael D. Griffin#Long-term vision for space

- NASA's Vision for Space Exploration

- Solar System

- Space architecture

- Space medicine

- Space weather

- The Case for Mars

- Water on Mars

References

- ^ ORACLE-ThinkQuest

- ^ Fong, MD, Kevin (12 February 2014). "The Strange, Deadly Effects Mars Would Have on Your Body". Wired (magazine). Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Gravity Hurts (so Good) - NASA 2001

- ^ "Mars Mice". science.nasa.gov. 2004.

- ^ Hamilton, Calvin. "Mars Introduction".

- ^ Elert, Glenn. "Temperature on the Surface of Mars".

- ^ Hecht, M.H. (2002). Metastability of Liquid Water on Mars. Icarus, 156 373–386.

- ^ Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (December 10, 2013). "NASA Mars Spacecraft Reveals a More Dynamic Red Planet". NASA. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ Coffey, Jerry (5 June 2008). "Air on Mars". Universe Today. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ John B. West (1 March 1999). "John B. West – Barometric pressures on Mt. Everest: new data and physiological significance (1998)". Jap.physiology.org. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ^ http://gltrs.grc.nasa.gov/reports/2002/TM-2002-211467.pdf

- ^ Baldwin, Emily (26 April 2012). "Lichen survives harsh Mars environment". Skymania News. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ de Vera, J.-P.; Kohler, Ulrich (26 April 2012). "The adaptation potential of extremophiles to Martian surface conditions and its implication for the habitability of Mars" (PDF). European Geosciences Union. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ Surviving the conditions on Mars - DLR

- ^ http://marsrover.nasa.gov/spotlight/20070612.html

- ^ centennialofflight.gov

- ^ sablesys.com

- ^ Technological Requirements for Terraforming Mars

- ^ MARIE reports and data

- ^ bnl.gov

- ^ Zubrin, Robert (1996). The Case for Mars: The Plan to Settle the Red Planet and Why We Must. Touchstone. pp. 114–116. ISBN 0-684-83550-9.

- ^ a b c Space Radiation Hinders NASA’s Mars Ambitions.

- ^ "Flight to Mars: How Long? And along what path?". Phy6.org. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ^ NASA Tech Briefs - Variable-Specific-Impulse Magnetoplasma Rocket

- ^ Ion engine could one day power 39-day trips to Mars

- ^ a b c Zubrin, Robert (1996). The Case for Mars: The Plan to Settle the Red Planet and Why We Must. Touchstone. ISBN 0-684-83550-9.

- ^ NASA: Space radiation between Earth and Mars poses a hazard to astronauts.

- ^ Dr. David R. Williams (2004-09-01 (last updated)). "Mars Fact Sheet". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Nancy Atkinson (2007-07-17). "The Mars Landing Approach: Getting Large Payloads to the Surface of the Red Planet". Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- ^ This is from an archived version of the web: The Space Elevator - Chapters 2 & 7 http://web.archive.org/web/20050603001216/www.isr.us/Downloads/niac_pdf/chapter2.html

- ^ Space Colonization Using Space-Elevators from Phobos Leonard M. Weinstein

- ^ Belluscio, Alejandro G. (March 7, 2014). "SpaceX advances drive for Mars rocket via Raptor power". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ^ marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov

- ^ Gangale, T. (2005). "MarsSat: Assured Communication with Mars". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1065: 296–310. Bibcode:2005NYASA1065..296G. doi:10.1196/annals.1370.007. PMID 16510416.

- ^ "Sun-Mars Libration Points and Mars Mission Simulations" (PDF). Stk.com. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ^ "A Novel Interplanetary Communications Relay" (PDF). Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ^ D. Kaplan et al., THE MARS IN-SITU-PROPELLANT-PRODUCTION PRECURSOR (MIP) FLIGHT DEMONSTRATION, paper presented at Mars 2001: Integrated Science in Preparation for Sample Return and Human Exploration, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Oct. 2-4 1999, Houston, TX.

- ^ G. A. Landis, P. Jenkins, D. Scheiman, and C. Baraona, "MATE and DART: An Instrument Package for Characterizing Solar Energy and Atmospheric Dust on Mars", presented at Concepts and Approaches for Mars Exploration, July 18–20, 2000 Houston, Texas.

- ^ NWT magazine, august 2012

- ^ "Elon Musk: I'll Put a Man on Mars in 10 Years". Market Watch. New York: The Wall Street Journal. 2011-04-22. Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

Coppinger, Rod (2012-11-23). "Huge Mars Colony Eyed by SpaceX Founder Elon Musk". Space.com. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

an evolution of SpaceX's Falcon 9 booster ... much bigger [than Falcon 9], but I don't think we're quite ready to state the payload. We'll speak about that next year. ... Vertical landing is an extremely important breakthrough — extreme, rapid reusability.

- ^ Landis, Geoffrey A. (2009). "Meteoritic steel as a construction resource on Mars". Acta Astronautica. 64 (2–3): 183. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2008.07.011.

- ^ Lovelock, James and Allaby, Michael, "The Greening of Mars" 1984

- ^ "Effect of Clouds and Pollution on Insolation". Retrieved 2012-10-04.

- ^ Space Settlement Basics by Al Globus, NASA Ames Research Center. Last Updated: February 02, 2012

- ^ "SpaceX Capabilities and Services". SpaceX. 2013. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ^ a b Belfiore, Michael (2013-12-09). "The Rocketeer". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (September 30, 2013). "Recycled rockets: SpaceX calls time on expendable launch vehicles". BBC News. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ A Journey to Inspire, Innovate, and Discover - Report of the President's Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy, June 2004

- ^ Fogg, Martyn J. (1997). "The utility of geothermal energy on Mars" (PDF). Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 49: 403–22. Bibcode:1997JBIS...50..187F.

- ^ G. E. Cushing, T. N. Titus, J. J. Wynne1, P. R. Christensen. "THEMIS Observes Possible Cave Skylights on Mars" (PDF). Retrieved June 18, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ http://mars-one.com/ Mars One - Initiative for establishing a fully operational permanent human colony on Mars by 2023.

Further reading

- Robert Zubrin, The Case for Mars: The Plan to Settle the Red Planet and Why We Must, Simon & Schuster/Touchstone, 1996, ISBN 0-684-83550-9

- Frank Crossman and Robert Zubrin, editors, On to Mars: Colonizing a New World. Apogee Books Space Series, 2002, ISBN 1-896522-90-4.

- Frank Crossman and Robert Zubrin, editors, On to Mars 2: Exploring and Settling a New World. Apogee Books Space Series, 2005, ISBN 978-1-894959-30-8.

- Resource Utilization Concepts for MoonMars; ByIris Fleischer, Olivia Haider, Morten W. Hansen, Robert Peckyno, Daniel Rosenberg and Robert E. Guinness; 30 September 2003; IAC Bremen, 2003 (29 Sept – 03 Oct 2003) and MoonMars Workshop (26-28 Sept 2003, Bremen). Accessed on 18 January 2010

- MARTIAN OUTPOST: The Challenges of Establishing a Human Settlement on Mars; by Erik Seedhouse; Praxis Publishing; 2009; ISBN 978-0-387-98190-1. Also see [1], [2]

- Ice, mineral-rich soil could support human outpost on Mars; by Sharon Gaudin; 27 June 2008; IDG News Service

External links

- Mars Society

- The Planetary Society: Mars Millennium Project

- 4Frontiers Corporation

- The Mars Foundation

- Making Mars the New Earth - National Geographic