Nineteen Eighty-Four

| Plume (Centennial Edition) Plume (Centennial Edition) | |

| Author | George Orwell |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dystopian, Political Novel |

| Publisher | Secker and Warburg |

Publication date | 8 June 1949 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) & e-book, audio-CD |

| Pages | 368 pp (Paperback edition) |

| ISBN | ISBN 0452284236 (Paperback edition) Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

Nineteen Eighty-Four is a political novel written by George Orwell in opposition to totalitarianism.[1] The book depicts a dystopia in which an omnipresent state wields total control.

Along with Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale, and Yevgeny Zamyatin's We (and possibly Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange), Nineteen Eighty-Four is among the most famous and most cited works of dystopian fiction in literature[2]. Translations of the book are available in 15 languages and the novel itself has left a profound impression upon the English language: Nineteen Eighty-Four and its terminology have become bywords in discussions concerning privacy issues. The term "Orwellian" has come to describe actions or organizations reminiscent of the totalitarian society depicted in the novel.

Novel history

Title

Originally Orwell titled the book The Last Man in Europe, but his publisher, Frederic Warburg, suggested a change to assist in the books marketing. [3] Orwell did not object to this suggestion. The reasons for the current title of the novel is not absolutely known. In fact, Orwell may have only switched the last two digits of the year in which he wrote the book (1948). Alternatively, he may have been making an allusion to the centenary of the Fabian Society, a socialist organization founded in 1884. The allusion may have also been directed to Jack London's novel The Iron Heel (in which the power of a political movement reaches its height in 1984), to G. K. Chesterton's The Napoleon of Notting Hill (also set in that year), or to a poem that his wife, Eileen O'Shaughnessy, had written, called End of the Century, 1984.

Orwell's inspiration

In his essay Why I Write, Orwell clearly explains that all the "serious work" he had written since the Spanish Civil War in 1936 was "written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism". (Why I Write) Therefore, one can look at Nineteen Eighty-Four as a cautionary tale against totalitarianism and in particular the betrayal of a revolution by those claiming to defend or support it. However, as many reviewers and critics have stated, it should not be read as an attack on socialism as a whole, but on totalitarianism (and potential totalitarianism).

Orwell had already set forth his distrust of totalitarianism and the betrayal of revolutions in Homage to Catalonia and Animal Farm. Coming Up For Air, at points, celebrates the individual freedom that is lost in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Orwell based many aspects of Oceanian society on the Stalin-era Soviet Union. The "Two Minutes' Hate", for instance was based on Stalinism's habitual demonization of its enemies and rivals, and the description of Big Brother himself bears a physical resemblance to Stalin. The Party's proclaimed great enemy, Emmanuel Goldstein, resembles Leon Trotsky, particularly in that both are Jewish.

Orwell's biographer Michael Shelden recognizes, as influences on the work: the Edwardian world of his childhood in Henley for the "golden country;" his being bullied at St. Cyprian's for feelings of victims toward tormentors; his life in the Indian Burma Police and his experiences with censorship in the BBC for models of authoritarian power. Specific literary influences Shelden mentions include Arthur Koestler's books Darkness at Noon and The Yogi and the Commissar; Jack London's The Iron Heel (1908); Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1930); Yevgeny Zamyatin's Russian novel We (1923), which Orwell first read in the 1940s; James Burnham's The Managerial Revolution (1940).[4] Orwell personally told Jacintha Buddicom that at some point he might write a book in a style similar to that of H. G. Wells' Modern Utopia.

His work for the overseas service of the BBC, which at the time was under the control of the Ministry of Information, also played a significant role as the basis for his Ministry of Truth (as he later admitted to Malcolm Muggeridge). The Ministry of Information building, Senate House (University of London), was the Ministry of Truth's architectural inspiration.

The world of Nineteen Eighty-Four also reflects various aspects of the social and political life of both the United Kingdom and the United States of America. Orwell is reported to have said that the book described what he viewed as the situation in the United Kingdom in 1948, when the British economy was poor, the British Empire was dissolving at the same time as newspapers were reporting its triumphs, and wartime allies such as the USSR were rapidly becoming peacetime foes ('Eurasia is the enemy. Eurasia has always been the enemy').

In many ways, Oceania is indeed a future metamorphosis of the British Empire (although Orwell is careful to state that, geographically, it also includes the United States, and that the currency is the dollar). It is, as its name suggests, an essentially naval power. Much of its militarism is focused on veneration for sailors and seafarers, serving on board "floating fortresses" which Orwell evidently conceived of as the next stage in the growth of ever-bigger warships, after the Dreadnoughts of WWI and the aircraft carriers of WWII; and much of the fighting conducted by Oceania's troops takes place in defence of India (the "Jewel in the Crown" of the British Empire).

The party newspaper is The Times, identified in Orwell's time (and to some degree even at present) as the voice of the British ruling class — rather than, as could have been expected, a publication which started life as the paper of a revolutionary party (like Pravda in the Soviet Union).

O'Brien, who represents the oppressive Party, is in many ways depicted as a member of the old British ruling class (in one case, Winston Smith thinks of him as a person who in the past would have been holding a snuffbox, i.e. an old-fashioned English gentleman).

The world of Nineteen Eighty-Four

Template:Spoiler The novel focuses on Winston Smith, who stands, seemingly alone, against the corrupted reality of his world: hence the work's original working name of The Last Man in Europe[5]. Although the storyline is unified, it could be described as having three parts (it has been published in three parts by some publishers). The first part deals with the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four as seen through the eyes of Winston; the second part deals with Winston's forbidden sexual relationship with Julia and his eagerness to rebel against the Party; and the third part deals with Winston's capture and torture by the Party.

The world described in Nineteen Eighty-Four contains striking parallels with the Stalinist Soviet Union and Hitler's Nazi Germany. There are thematic similarities: the betrayed-revolution, with which Orwell famously dealt with in Animal Farm; the subordination of individuals to "the Party"; and the rigorous distinction between inner party, outer party and everyone else. There are also direct parallels of the activities within the society: leader worship, such as that towards Big Brother, who can be compared to dictators like Stalin and Hitler; Joycamps, which are a reference to concentration camps or gulags; Thought Police, a reference to the Gestapo or NKVD; daily exercise reminiscent of Nazi propaganda movies; and the Youth League, reminiscent of Hitler Youth or Octobrists/Pioneers.

There is also an extensive and institutional use of propaganda; again, this was found in the totalitarian regimes of Hitler and Stalin. Orwell may have drawn inspiration from the Nazis; compare the following quotes to how propaganda is used in "Nineteen Eighty-Four":

- Nazis

- “The broad mass of the nation ... will more easily fall victim to a big lie than to a small one.” — Adolf Hitler, in his 1925 book Mein Kampf.

- “If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it.” — Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. [6]

- Nineteen Eighty-Four

- “Remember our boys on the Malabar front! And the sailors in the Floating Fortresses! Just think what they have to put up with.”

- “The rocket bombs which fell daily on London were probably fired by the government of Oceania itself, 'just to keep the people frightened'.”

- “The key-word here is blackwhite. Like so many Newspeak words, this word has two mutually contradictory meanings. Applied to an opponent, it means the habit of impudently claiming that black is white, in contradiction of the plain facts.”

- “To tell deliberate lies while genuinely believing in them, to forget any fact that has become inconvenient, and then when it becomes necessary again, to draw it back from oblivion for just so long as it is needed.”

Summary of plot

Winston, a member of the Outer Party, lives in the ruins of London, the chief city of Airstrip One — a front-line province of the totalitarian superstate Oceania. He grew up in post-Second World War Britain, during the revolution and civil war. When his parents died during the civil war, he was picked up by the growing Ingsoc (newspeak for "English Socialism") movement and given a job in the Outer Party.

Winston lives a squalid existence in a filthy one-room apartment in "Victory Mansions", and eats hard bread, synthetic meals served at his workplace, and industrial-grade "Victory Gin." He is unhappy and keeps a secret diary of his illegal thoughts about the Party. The Ministry of Truth, which exercises complete control over all media in Oceania, employs Winston at the Ministry's Records Department, where he doctors historical records in order to comply with the Party's version of the past. Since the events of the present constantly shape the perception of the past, the task is a never-ending one.

While Winston likes his work, especially the intellectual challenge involved in fabricating a complete historical anecdote from scratch, he is also fascinated by the real past, and eagerly tries to find out more about the forbidden truth. At the Ministry of Truth, he encounters Julia, a mechanic on the novel-writing machines, and the two begin an illegal relationship, regularly meeting up in the countryside (away from surveillance) or in a room above an antique shop in the Proles' area of the city.

As the relationship progresses, Winston's views begin to change, and he finds himself relentlessly questioning Ingsoc. Unknown to the two (or to the reader), he and Julia are under surveillance by the Thought Police. When he is approached by Inner Party member O'Brien, Winston believes that he has made contact with the Resistance. O'Brien gives Winston a copy of "the book", a searing criticism of Ingsoc that Smith believes the dissident Emmanuel Goldstein wrote.

Winston and Julia are apprehended by the Thought Police and interrogated separately in the Ministry of Love, where opponents of the regime are tortured and executed. O'Brien reveals to Winston that he has been brought to "be cured" of his hatred for the Party, and subjects Winston to numerous torture sessions. During one of these sessions, he explains to Winston the nature of the endless world war, and that the purpose of the torture is not to extract a fake confession, but to change the way Winston thinks.

This is achieved through a combination of torture and electroshock therapy, until O'Brien decides that Winston is "cured". However, Winston unconsciously utters Julia's name in his sleep, proving that he has not been completely brainwashed. Room 101 is the most feared room in the Ministry of Love, where a person's greatest fear is forced upon them as the final step in their "re-education." Since Winston is afraid of rats, a cage of hungry rats is placed over his eyes, so that when the door is opened, they will eat their way through his skull.

In terror, he screams, "Do it to Julia!" to stop the torture. At the end of the novel, Winston and Julia meet, but their feelings for each other have been destroyed. Winston has become an alcoholic and he knows that eventually he will be killed. The one thing Winston had held on to was his hate of Big Brother, which he felt would be his victory over the party's otherwise absolute power. However, by the end of the novel, we see that the torture and 'reprogramming' have been successful, because Winston realizes that 'He loved Big Brother'.

At the end of the novel there is an appendix on Newspeak (the artificial language invented and, by degrees, imposed by the Party to limit the capacity to express or even think "unorthodox" thoughts), in the style of an academic essay.

Backstory to novel

| The War of Nineteen Eighty-Four | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II and the Cold War | |||||||||

From top clockwise: The Russian invasion of Finland, the Soviet-Japan War, Clement Attlee's socialist victory, the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty. Several historical forerunners of Orwell's world. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Americas British Isles Australia |

Soviet Union Europe East Asia | ||||||||

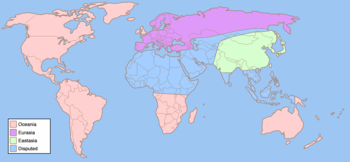

The novel does not give a full history of how the world of 1984 came into being. Winston's recollections, and what he reads from "The Book" (i.e., Goldstein's book) reveal that at some point after the Second World War, the United Kingdom descended into civil war, eventually becoming part of the new world power of Oceania. At roughly the same time, the Soviet Union expanded into mainland Europe to form Eurasia; and the third world power, Eastasia — an amalgamation of east Asian countries including China and Japan — emerged some time later.

There was a period of nuclear warfare during which some hundreds of atomic bombs were dropped, mainly on Europe, western Russia, and North America. (The only city that is explicitly stated to have suffered a nuclear attack is Colchester.) It is not clear what came first — the civil war which ended with the Party taking over, the absorption of Britain by the US, or the external war in which Colchester was bombed.

In articles written during the Second World War, Orwell repeatedly expressed the idea that British democracy as it existed before 1939 would not survive the war, the only question being whether its end would come through a Fascist takeover from above or by a Socialist revolution from below. (The second possibility, it should be noted, was greatly supported and hoped for by Orwell, to the extent that he joined and loyally participated in "the Home Guard" throughout the war, in the expectation that that body would become the nucleus of a revolutionary militia). After the war ended Orwell openly expressed his surprise that events had proven him wrong.[7]

English Socialism

The most complete expression of Orwell's predictions in that direction is contained in "The Lion and the Unicorn" which he wrote in 1940. There, he stated that "the war and the revolution are inseparable (...) the fact that we are at war has turned Socialism from a textbook word into a realizable policy". The reason for that, according to Orwell, was that the outmoded British class system constituted a major hindrance to the war effort, and only a Socialist society would be able to defeat Hitler. Since the middle classes were in process of realizing this, too, they would support the revolution, and only the most outright Reactionary elements in British society would oppose it — which would limit the amount of force the revolutionaries would need in order to gain power and keep it.

Thus, an "English Socialism" would come about which "...will never lose touch with the tradition of compromise and the belief in a law that is above the State. It will shoot traitors, but it will give them a solemn trial beforehand and occasionally it will acquit them. It will crush any open revolt promptly and cruelly, but it will interfere very little with the spoken and written word".

Such a revolutionary regime, which Orwell found highly desirable and was actively trying to bring about in 1940, is of course a far cry from the monstrous edifice presided over by Big Brother, which was his nightmare a few years later. Still, one can see how the one may degenerate into the other (and The Party does provide "traitors" with "a solemn trial" before shooting them...)

The term "English Socialism", repeated numerous times in "The Lion and the Unicorn", is rather parochial — had events developed as Orwell predicted, the Scots and Welsh would have undoubtedly had a major share in such a revolution. Its importance for understanding "1984" is that the official Party ideology is "Ingsoc", an abbreviation of "English Socialism". This shows that Orwell perceived of the monstrous regime that he described in “1984”, as not only a betrayal and perversion of Socialist ideals in general, but also as a perversion of Orwell’s own specifically and dearly cherished vision and hope of Socialism. [8]

In 1940 Orwell was quite optimistic about the chances of Socialism — his brand of Socialism. In 1947, when he wrote "Toward European Unity" he was far more pessimistic (which may have had to do, not only with objective conditions in the world, but also with his fast deteriorating health). He no longer had hopes in the possibility of a Socialist revolution in Britain alone. The only real chance (and he considered it a slim chance) was through a Socialist Federation of Western Europe, "The only region where for a large number of people the word Socialism is bound up with liberty, equality and internationalism". Such a federation, embracing some 250 million people, would provide a large-scale working model of "a community where people are relatively free and happy and where the main motive in life is not the pursuit of money or power".

Many preconditions had to be fulfilled for that vision to materialise. The Western European countries had to remain independent both of the Soviet military might and of looking to the Soviet Union for their model of Socialism. Britain had to divest itself of its empire, since exploiting the labour of colonial masses was incompatible with building a true Socialist society. It also had to cut itself completely out of the American orbit, and ally with the West European countries in a common revolution. Orwell was not sanguine about the chances of all these conditions materialising, but stated in conclusion, "One thing in our favour is that a major war is not likely to happen immediately" — which would at least give some breathing space to the forces seeking Democratic Socialism.[9]

"Nineteen Eighty-Four" was written at almost precisely the same time as "Toward European Unity", and the fictional history unfolding in the past of the novel could be considered as the exact mirror image of that article. A major war does break out almost "immediately" from the time of writing in 1948, the opposite happens of all the indispensable conditions for Democratic Socialism, and things deteriorate.

From the memories of Winston, scattered through the book, one can try to piece out the following:

- At the outbreak of war, when Colchester was A-bombed, the child Winston experienced an air-raid alarm and his parents took him to a tube station, where he heard an old man saying, "We didn't ought to 'ave trusted them". This implies a sense of betrayal, felt in the British public in the aftermath of a surprise attack. The context would suggest a Soviet attack, possibly after a period of relative rapprochement or a failed peace effort.

- The outbreak of war might have followed the withdrawal of US forces from Europe — a quite plausible future development when the book was written, before the creation of NATO and when the main available precedent was the American withdrawal from Europe in the aftermath of WWI. That would account both for the feeling of betrayal and for the Soviet success in sweeping, while Britain was heavily bombed but protected by the Channel from a ground invasion, westwards to the Atlantic and southwards into the Middle East. (A newsreel from the Middle East which Smith watches shows a boat full of Jewish refugees being sunk by an Oceanian helicopter; evidently, in this history the state of Israel, founded in 1948, had had only an ephemeral existence.)

- The major invasion was followed by the Soviet Union being transformed into "Eurasia" and adopting the ideology of "Neo-Bolshevism" (possibly under the impact of absorbing the Communists of France, Italy etc. into its ruling party).

- The isolated Britain kept its empire and was perforce drawn into a closer alliance and eventual political amalgamation with the United States — that might have been the time when the dollar became the common currency.

- At that time, Winston's father was still around and his sister was not yet born. The time must be the early 1950s, since he was born in 1944 or 1945 and these are for him dim childhood memories; in other words, for Orwell writing in 1948 this was in the very near future. Winston is about the same age as Richard Horatio Blair, Orwell's adopted son, who was born in May 1944.

- After that, the war in Europe seems to have stabilized into exchanges of aerial bombardments (by tacit agreement avoiding the use of nuclear arms) and to naval blockades and submarine warfare, with ground battles confined to extra-European theatres. In effect, Orwell conceived the future war as taking virtually the same course that WWII took in 1940 after the Fall of France. This is the period from which come Winston's later childhood memories, a time when the father was gone and the mother was left alone with Winston and the baby sister.

- That was a time of very great economic privations — much worse even than the systematised and controlled privations which daily life in 1984 Oceania entails. There was presumably the destruction left by nuclear bombardment, which destroyed a part of Britain's industrial capacity, and also left agricultural areas contaminated ("1984" mentions Winston and Julia meeting in countryside areas still devastated and deserted after 30 years), the need to fight a full-scale war again without being fully recovered from the effects of WWII (in our history Britain only fully recovered in the 1950s, and in 1948 when Orwell wrote, there were predictions of a much longer time needed for recovery).

To these would be added Soviet/Eurasian attacks on the supply lines, for which (unlike with Nazi Germany in WWII) the coasts of Spain, Portugal and North Africa, as well as those of France, would be fully available for Soviet/Eurasian submarine bases and airfields. (The development of the "virtually unsinkable" Floating Fortresses might have come later, as a means of securing the Atlantic sea-lanes and ensuring at least a trickle of vital supplies to Britain/Airstrip One — which would explain the popularity of the sailors serving in these fortresses, used in the Party's propaganda. The Floating Fortresses might have been inspired by WWII Project Habakkuk's virtually unsinkable reinforced ice aircraft carriers, if Orwell had heard of them.)

Winston's memories of this time are full of political chaos and violence, as seen through an uncomprehending child's eyes. There is a specific mention of rival militias roaming the streets, each one composed of boys all wearing shirts of the same colour (a vision which Orwell might have taken from the last years of Weimar Germany, where Nazi, Communist and other militias constantly fought in the streets).

That corresponds, presumably, to the time when The Party (which at the time must still have had a name, being only one of several contending parties) was led by Jones, Aaronson, and Rutherford, and Big Brother had not yet risen to prominence. (The three are clearly modelled on Bukharin, Zinoviev and Kamenev, the prominent Bolshevik leaders whom Stalin supplanted and executed).

Apparently, Orwell conceives of the three as sincere revolutionaries moved by outrage at the injustice of capitalism. There is the specific mention of Rutherford's "brutal cartoons", depicting slum tenements, starving children, street battles and capitalists in top hats, which "helped inflame popular opinion before and during the Revolution". The revolutionaries eventually win — or so it seems. What Orwell hoped for in vain during WWII does take place during the WWIII of the 1950s, Orwell's immediate future — a revolution in Britain. But now he sees it as the beginning of a nightmare, not of hope.

The difference can be partly explained by the fact that the revolution takes place in far more brutal conditions than those of WWII Britain where Orwell hoped for a relatively mild revolution — and more similar to the conditions of 1917 in Russia from which the incipient Soviet regime had its introduction to brutality. While Rutherford's cartoons were obviously exaggerated, in order to be so effective in rousing public fury they must have reflected, to some degree, the reality of deep privations and social polarization in the immediate pre-revolutionary time.

Under such conditions, the revolutionaries' victory could have easily been accompanied by widespread retaliations against "war profiteers" and "fat cats" (there was widespread resentment against such people in WWII Britain). Such retaliations, condoned as "unavoidable excesses", would have set the new regime on a road of arbitrary brutality from its very inception.

Also, Orwell's essential conditions for the revolution to develop towards Democratic Socialism, set out in "Toward European Unity", were all not fulfilled — Western Europe is occupied and in no condition to join in the revolution, and Britain is inextricably tied to both the U.S. and to its oppressive overseas empire. Indeed, the brutal all-out exploitation of colonial peoples as semi-slave labour could have been started by the old regime in the immediate aftermath of the occupation of Europe, as a desperate measure of survival, and deepened rather than abolished by the newly arrived revolutionaries. Altogether, the revolutionary regime was inexorably perverted into the merciless tyranny of Big Brother.

At some time soon after, the revolution, which started in Britain, spread to the United States and won there as well. This is simply mentioned, with no detail and no information of the situation in the American part of Oceania beyond a passing mention of a Party congress in New York and a reference in "The Book" to "Jews, Negroes and South Americans of pure Indian blood" being "found in the highest ranks of the Party". The Americas are not part of this story any more than the detailed history of China; it is just a faraway place of which almost no information is given.

The later history of Oceania seems modelled, in a rather one-to-one basis, on Soviet history. Oceania's 1950s are based on the Soviet 1920s, a time of civil war and revolutionary turmoil. Similarly, the 1960s are the 1930s, the time when Stalin/Big Brother, consolidated his power and smothered all opposition. (Stalin's Moscow Show Trials took place in 1936, Big Brother's equivalent in 1965). By the end of the 1960s, Big Brother has completed the process of turning the revolution into a pretext for creating a terror state.

By the year 1984, the citizens of Oceania had been separated into three distinct, isolated classes — the Inner Party, the Outer Party, and the proles. However, in the view of Emmanuel Goldstein (which seems to be Orwell's) these are but new names for classes which have essentially existed throughout human history — though under the new dispensation they are more rigid and unchangeable than ever before.

On the global level, as "The Book" (supposedly written by Emmanuel Goldstein though in fact its descriptive part turns out to be endorsed by the Party) explains, the three powers eventually realized that continuous stalemate war was preferable to conquest, as war allowed them to spend their surplus labour manufacturing products that would be wasted during fighting, rather than improving people's standards of living (an impoverished population being easier to control than a rich one).

By the time the novel is set, the three powers have taken over most of the world, but they still fight over a large area. This area, containing the northern half of Africa, the Middle East, southern India, Indonesia, and northern Australia, provides slaves, or low-paid workers who are effectively slaves, for all three powers.

The powers rarely if ever fight on their own territory — Airstrip One (the official name of Great Britain) has become the target of Eurasian rocket bombs, but it is hinted that the Oceanian government itself may launch these weapons in order to convince the population that it is under constant attack.

Ministries of Oceania

Oceania's four ministries are housed in huge pyramidal structures, each roughly 300 metres high and visible throughout London, displaying the three slogans of the party (see below) on their facades.

- The Ministry of Peace

- Newspeak: Minipax.

Concerns itself with conducting Oceania's perpetual wars. - The Ministry of Plenty

- Newspeak: Miniplenty.

Responsible for rationing and controlling food and goods. - The Ministry of Truth

- Newspeak: Minitrue.

The propaganda arm of Oceania's regime. Minitrue controls information: political literature, the Party organization, and the telescreens. Winston Smith works for Minitrue, "rectifying" historical records and newspaper articles to make them conform to Big Brother's most recent pronouncements, thus making everything that the Party says true. - The Ministry of Love

- Newspeak: Miniluv.

The agency responsible for the identification, monitoring, arrest, and torture of dissidents, real or imagined. Based on Winston's experience there at the hands of O'Brien, the basic procedure is to pair the subject with his or her worst fear for an extended period, eventually breaking down the person's mental faculties and ending with a sincere embrace of the Party by the brainwashed subject. The Ministry of Love differs from the other ministry buildings in that it has no windows in it at all.

The ministries' names are ironic — the Ministry of Peace makes war, the Ministry of Plenty oversees shortages, the Ministry of Truth spreads propaganda and lies, and the Ministry of Love inflicts misery. However, from the perspectives of the Oceanians who accept the propaganda, these names are accurate.

The Party

In his novel, Orwell created a world in which citizens have no right to a personal life or to personal thought. Leisure and other activities are controlled through a system of strict mores. Sexual pleasure is discouraged; sex is retained only for the purpose of procreation, although artificial insemination (ARTSEM) is more encouraged.

The mysterious head of government is the omniscient, omnipotent, beloved Big Brother, or "B.B.", usually displayed on posters with the slogan "BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU". However, it is never quite clear whether Big Brother truly exists or not, or whether he is a fictitious leader created as a focus for the love of the Party which the Thought Police and others are there to engender (it is possible that he is real, but we — and the book's characters — never know for certain). It is perfectly possible that the conflict between Big Brother and Emmanuel Goldstein is in fact a conflict either between two fictitious or dead leaders, whose true purpose is to personify both the Party and its opponents.

His political opponent (who is therefore a criminal) is the hated Goldstein, a Party member who the reader is told had been in league with Big Brother and the Party during the revolution. Goldstein is said to be the leader of the Brotherhood, a vast underground anti-Party fellowship. The reader never truly finds out whether the Brotherhood exists or not, but the implication is that Goldstein is either entirely fictitious or was eliminated long ago. Party members are expected to vilify Goldstein, the Brotherhood and whichever superstate Oceania is currently warring via the daily "two minutes hate."

A typical two-minutes hate is depicted in the novel, during which citizens ridicule and shout at a video of the hated "bleating" Goldstein as he releases a litany of attacks upon Oceanic governance (indeed, the image ultimately morphs into a bleating sheep) on a background of enemy soldiers (in the book's portrayal of the two minutes they are Eurasian, but after the switch to the war with Eastasia, it is expected that the background changes to Eastasian soldiers).

The three slogans of the Party, on display everywhere, are:

- WAR IS PEACE

- FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

- IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH

Each of these is of course either contradictory or the opposite of what we normally believe, and in 1984, the world is in a state of constant war, no one is free, and everyone is ignorant. The slogans are analysed in Goldstein's book. Though logically insensible, the slogans do embody the Party. For instance, through constant "war", the Party can keep domestic peace; when freedom is brought about, the people are enslaved to it, and the ignorance of the people is the strength of the Party. If (like Winston) anybody becomes too smart, they are whisked away for fear of rebellion. Through their constant repetition, the terms become meaningless, and the slogans become axiomatic. This type of misuse of language, and the deliberate self-deception with which the citizens are encouraged to accept it, is called doublethink.

One essential consequence of doublethink is that the Party can rewrite history with impunity, for "The Party is never wrong." The ultimate aim of the Party is, according to O'Brien, to gain and retain full power over all the people of Oceania; he sums this up with perhaps the most distressing prophecy of the entire novel: If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face — for ever.

Political geography

The world is controlled by three functionally similar totalitarian superstates engaged in perpetual war with each other:

- Oceania (ideology: Ingsoc or English Socialism),

- Eurasia (ideology: Neo-Bolshevism), and

- Eastasia (ideology: Obliteration of the Self, usually rendered as "Death worship").

In terms of the political map of the late 1940s when the book was written, Oceania covers the greater part of the British Empire (or the Commonwealth), and the Americas, Eastasia corresponds to China, Japan, Korea, and northern India. Eurasia corresponds to the Soviet Union and Continental Europe.

That Great Britain is in Oceania rather than in Eurasia is commented upon in the book as a historical anomaly. North Africa, the Middle East, southern India, and South East Asia form a disputed zone which is used as a battlefield and source of slaves by the three powers. Goldstein's book explains that the ideologies of the three states are the same, but it is imperative to keep the public ignorant of that. The population is led to believe that the other two ideologies are detestable. London, the novel's setting, is the capital of the Oceanian province of Airstrip One, the former Great Britain.

The war

| Eternal War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II and the Cold War | |||||||

The attacks described as black (Eurasian) and white (Oceanian) arrows in the last chapter of the novel. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Oceania |

Eurasia Eastasia | ||||||

The world of Nineteen Eighty-Four is built around an endless war involving the three global superstates, with two allied powers fighting against the third. The allied states occasionally split with each other and new alliances are formed, but as Goldstein's book explains, this does not matter, as each superstate is so strong it cannot be defeated even when faced with the combined forces of the other two powers. The war rarely takes place on the territory of the three powers, and actual fighting is conducted in the disputed zone stretching from Morocco to Australia, and in the unpopulated Arctic wastes. Throughout the first half of the novel, Oceania is allied with Eastasia, and Oceania's forces are engaged with fighting Eurasian troops in northern Africa.

Mid-way through the novel, the alliance breaks apart and Oceania, newly allied with Eurasia, begins a campaign against Eastasian forces in India. During "Hate Week" (a week of extreme focus on the evilness of Oceania's enemies), Oceania and Eurasia are enemies once again. The public is quite blind to the change, and when a speaker, mid-sentence, changes the enemy from Eurasia to Eastasia (speaking as if nothing had changed), the people are shocked as they notice all the flags and banners are wrong (they blame Goldstein and the Brotherhood) and quite effectively tear them down.

The book that Winston receives explains that the war is unwinnable, and that its only purpose is to use up human labor and the fruits of human labor so that each superstate's economy cannot support an equal (and high) standard of living for every citizen. The book also details an Oceanian strategy to attack enemy cities with atomic-tipped rocket bombs prior to a full-scale invasion, but quickly dismisses this plan as both infeasible and contrary to the purpose of the war.

Although, according to Goldstein's book, hundreds of atomic bombs were dropped on cities during the 1950s, the three powers no longer use them, as they would upset the balance of power. Conventional military technology is little different from that used in the Second World War. Some advances have been made, such as replacing bomber aircraft with "rocket bombs", and using immense "floating fortresses" instead of battleships, but such advances appear to be rare. As the purpose of the war is to destroy manufactured products and thus keep the workers busy, obsolete and wasteful technology is deliberately used in order to perpetuate useless fighting.

Goldstein's book hints that in fact, there may not actually be a war. The only view of the outside world presented in the novel is through Oceania's media, which has an obvious tendency to exaggerate and even fabricate "facts". Goldstein's book suggests that the three superpowers may not actually be at war, and as Oceania's media provide scarcely believable news reports on impossibly huge military campaigns and victories (including an impossibly large campaign in the Sahara desert), it can be suggested that the war, in fact, is a lie. However, as with many facets of the novel, the disputed existence of a war is neither confirmed nor denied, and the reader cannot be sure whether a war actually is in progress. In fact, it is entirely possible that the other two powers themselves are fabrications, and the entire world is controlled by a single entity.

It is noted in the novel that there are no longer massive battles, but rather, highly expert fighters occasionally appearing in skirmishes. This may be relatively paradoxical considering the massive amounts of resources wasted to keep the war effort running, given that so few soldiers are actually fighting.

Living standards

By the year 1984, the society of Airstrip One lives in abject squalor and poverty. Hunger, disease, and filth have become the social norm. As a result of the civil war, atomic wars, and Eurasian rocket bombs, the urban areas of Airstrip One lie in ruins. When travelling around London, Winston is surrounded by rubble, decay, and the crumbling shells of wrecked buildings.

Apart from the gargantuan bombproof Ministries, very little seems to have been done to rebuild London, and it is assumed that all towns and cities across Airstrip One are in the same desperate condition. Living standards for the population are generally very low — everything is in short supply and those goods that are available are of very poor quality. The Party claims that this is due to the immense sacrifices that must be made for the war effort. They are partially correct, since the point of continuous warfare is to be rid of the surplus of industrial production to prevent the rise of the standard of living and make possible the economic repression of people.

The Inner Party, at the top level of Oceanian society, enjoys the highest standard of living. O'Brien, a member of the Inner Party, lives in a relatively clean and comfortable apartment, and has access to a variety of quality foodstuffs such as wine, coffee, and sugar, none of which is available to the rest of the population. Members of the Inner Party also seem to be waited on by slaves captured from the disputed zone.

Although the Inner Party enjoys the highest standard of living, Goldstein's book points out that, despite being at the top of society, their living standards are far, far below those of society's elite before the revolution. The proles, treated by the Party as animals, live in squalor and poverty. They are kept sedate with vast quantities of cheap beer, widespread pornography, and a national lottery, but these do not mask the fact that their lives are dangerous and deprived — proletarian areas of the cities, for example, are ridden with disease and vermin.

However, the proles are subject to much less close control of their daily lives than Party members, and the proles, which Winston Smith meets in the streets, and in the pubs seem to speak and behave much like working-class Englishmen of Orwell's time. In addition, the prole criminals whom he meets in the first phase of his imprisonment are far less subdued and intimidated than the intellectual "politicals", some of them rudely jeering at the telescreens with apparent impunity.

As explained in Goldstein's book, this derives from the social theory which the regime believes in — and which seems to work in the framework of the book — namely, that revolutions are always started by the middle class and that the lower classes would never start an effective rebellion on their own. Therefore, if the middle classes are so tightly controlled that the regime can penetrate their very thoughts and their most minute daily life, the lower classes can be left to their own devices and pose no threat.

As Winston is a member of the Outer Party, we discover more about the Outer Party's living standards than any other group. Despite being the middle class of Oceanian society, the Outer Party's standard of living is very poor. Foodstuffs are low quality or synthetic; the main alcoholic beverage — Victory Gin — is industrial-grade; Outer Party cigarettes are shoddy.

The subjects of Nineteen Eighty-Four

Nationalism

Nineteen Eighty-Four expands upon the subjects summarised in Orwell’s preparatory essay, Notes on Nationalism (1945): [2]. In it, Orwell expresses frustration at the lack of vocabulary needed to explain an unrecognised phenomenon that he felt was behind certain forces. He addresses this problem in Nineteen Eighty-Four by inventing the jargon of Newspeak.

A fictional society, to which the readers have no preconceived bias, was a tool in illustrating why Orwell thought examples shown below were different manifestations of the same forces at work, despite their being ideologically incompatible.

Positive nationalism

This is apparent in the novel, in the Oceanians’ undying love for Big Brother, whose physical existence is doubtful. Orwell lists Celtic Nationalism, Neo-Toryism and Zionism as examples of positive nationalism.

Negative nationalism

This is apparent in the novel, in the Oceanians’ undying hatred for Goldstein, whose continued existence is doubtful. Orwell lists Stalinism, Anti-Semitism and Anglophobia as examples of negative nationalism.

Transferred nationalism

In the novel, an orator, mid-sentence, alters the alleged enemy of Oceania, and the crowd instantly transfer their same feelings of hatred toward the new alleged enemy. In Notes on Nationalism, Orwell describes transferred nationalism as swiftly redirecting emotions from one power unit to another, as if not by reasoned change in opinion, but as if one’s beliefs are serving one’s loyalties, which can be altered, but with the original fanaticism intact. Orwell lists Communism, Political Catholicism, Pacifism, Colour Feeling, and Class Feeling as examples of transferred nationalism.

O'Brien, in one of his most conclusive statements, describes nationalism for its own sake: “The object of power is power; The object of torture is torture.”

Sexual repression

In the novel, Julia describes party fanaticism as "sex gone sour;" Winston, aside from during his affair with Julia, suffers from an ankle inflammation, alluding to Oedipus Rex and symbolizing an unhealthy repression of the sex drive. Orwell supposed that the sufficient mental energy for prolonged worship requires the repression of a vital instinct, such as the sex instinct. This possibly alludes to the restrictions on sexuality imposed by authorities (civil, political, religious or otherwise, such as in the German National-socialist regime), be it consciously or by selective pressures on doctrine.

Futurology

It is not clear to what extent Orwell believed his work was prophetic.

He describes what he believed was the future of England in his essay England, Your England:

- "The intellectuals who hope to see it Russianised or Germanised will be disappointed. The gentleness, the hypocrisy, the thoughtlessness, the reverence for law and the hatred of uniforms will remain, along with the suet puddings and the misty skies. It needs some very great disaster, such as prolonged subjugation by a foreign enemy, to destroy a national culture. The Stock Exchange will be pulled down, the horse plough will give way to the tractor, the country houses will be turned into children's holiday camps, the Eton and Harrow match will be forgotten, but England will still be England, an everlasting animal stretching into the future and the past, and, like all living things, having the power to change out of recognition and yet remain the same."

This is in stark contrast to O'Brien's forecast:

- "There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed. But always — do not forget this, Winston — always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face ...for ever."

Appendix on Newspeak

The novel includes an appendix, The Principles of Newspeak [3], written in the style of an academic essay. The appendix describes the development of Newspeak, and explains how the language is designed to standardise thought to reflect the ideology of Ingsoc; that is, by making "all other modes of thought impossible".

The fact that the appendix is written in the past tense, as well as other grammatical and non-grammatical features, has led some to argue that it can be seen to be describing Newspeak, and by extension Ingsoc, as a thing of the past, possibly implying a more ambiguous ending for the novel than is commonly thought (Atwood [4], Benstead [5]). However, there is no explicit statement in the appendix to suggest that it existed or was written in the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four, and it could simply be a part of the third person narrative that is deployed throughout the rest of the novel.

Furthermore, it could be argued that Orwell, as an advocate of plain English, would be unlikely to underpin such a significant plot detail with such a subtle clue.

Cultural impact

Nineteen Eighty-Four has had a surprisingly large impact on the English language. Many of its concepts, Big Brother, Room 101, thought police, doublethink and Newspeak, have entered common usage in describing totalitarian or overarching behaviour by authority. Doublespeak or doubletalk is a subsequent elaboration on the word doublethink that never actually appeared in the novel itself. The adjective "Orwellian" is often used to describe any real world scenario reminiscent of the novel. The practice of suffixing words with "-speak" and "-think" (groupthink, mediaspeak) arguably originated with the novel.

Controversy

In 1981, Jackson County in the U.S. state of Florida challenged the novel on the grounds that the book was "pro-communist and contained explicit sexual matter." [6] Supporters of the book have called this accusation preposterous, saying it casts more light on the accusers than the book.

The book's proponents admit that there are some passages relating to sex, and some to torture, but they are by no means extreme for the time, and are quite germane to the plot. Still, some people have objected to the book for those depictions.

Another criticism that can be leveled is that of anti-semitism. Goldstein, who is described as having "a Jewish face", is held up as "the Enemy of the People" by the Party, and is the subject of the Two Minutes Hate. However, it can be argued that the Party is seen throughout the book as evil, making its main opponent Jewish cannot be seen as an anti-Semitic attitude on the part of Orwell (and could even be seen, on the contrary, as reflecting Orwell's admiration of Jews). In fact, the Soviet Union was anti-Semitic in some ways, and the Goldstein character may reflect this. In addition, some aspects of Nineteen Eighty-Four seem modelled after Nazi Germany.

Other media

Nineteen Eighty-Four has been adapted for the cinema twice, for the radio twice, and for television at least once. References to its themes, concepts and elements of its plot are also frequent in other works, particularly popular music and video entertainment. For an incomplete but extensive list of these adaptations and references, see the related article.

See also

- Asch conformity experiments

- Censorship under fascist regimes

- Dystopia

- Language and thought

- Mass surveillance

- Memory hole

Bibliography

- Orwell, George. (1949). Nineteen-Eighty-Four. London: Secker & Warburg. (later edn. ISBN 0451524934)

- Aubrey, Crispin & Chilton, Paul (Eds). (1983). Nineteen-Eighty-Four in 1984: Autonomy, Control & Communication. London: Comedia. ISBN 0-906890-42X.

- Hillegas, Mark R. (1967). The Future As Nightmare: H.G. Wells and the Anti-Utopians. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-809-30676-X

- Howe, Irving (Ed.). (1983). 1984 Revisited: Totalitarianism In Our Century. New York: Harper Row. ISBN 0-060-80660-5.

- Shelden, Michael. (1991). Orwell — The Authorised Biography. London: Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-695173

- Smith, David & Mosher, Michael. (1984). Orwell for Beginners. London: Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative. ISBN 0-86316-066-2

- Tuccille, Jerome. (1975). Who's Afraid of 1984? The case for optimism in looking ahead to the 1980s. New York: Arlington House. ISBN 0-87000-308-9.

- West, W. J. The Larger Evils – Nineteen Eighty-Four, the truth behind the satire. Edinburgh: Canongate Press. 1992. ISBN 0-86241-382-6

References

- ^ "Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it." [1]

- ^ Marcus, Laura (2005). The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century English Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521820774.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) p. 226: "Brave New World [is] traditionally bracketed with Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four as a dystopia..." - ^ (Crick, Bernard. "Introduction," to George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984)). Published on June 8, 1949, the bulk of the novel was written by Orwell on the Scottish island of Jura in 1948, although he had been writing it since 1945. It begins on April 4, 1984 at 13:00 [1:00 P.M.] ("It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen...").

- ^ Shelden, Michael (1991). Orwell—The Authorized Biography. New York: HarperCollins. 0060167093.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); pp 430-434 - ^ http://www.orwell.ru/a_life/dystopia/e/e_dyst.htm

- ^ http://www.robert-fisk.com/the_evidence.htm

- ^ http://www.socialistreview.org.uk/article.php?articlenumber=8511

- ^ http://whitewolf.newcastle.edu.au/words/authors/O/OrwellGeorge/essay/lionunicorn.html

- ^ http://www.orwell.ru/library/articles/European_Unity/english/e_teu

- Atwood, Margaret (16 June 2003). "Orwell and me". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 November 2005.

- Benstead, James (26 June 2005). "Hope Begins in the Dark: Re-reading Nineteen Eighty-Four". Retrieved 20 November 2005.

- Orwell, George (1949). Nineteen eighty-four, "Appendix: The Principles of Newspeak", pp. 309–323. New York: Plume, 2003.

Pynchon, Thomas (2003). "Foreword to the Centennial Edition" to Nineteen eighty-four, pp. vii–xxvi . New York: Plume, 2003.

Fromm, Erich (1961). "Afterword" to Nineteen eighty-four, pp. 324–337. New York: Plume, 2003.

Orwell's text has a "Selected Bibliography", pp. 338–9; the foreword and the afterword each contain further references.

Copyright is explicitly extended to digital and any other means.

Plume edition is a reprint of a hardcover by Harcourt. Plume edition is also in a Signet edition.

External links

ELECTRONIC EDITIONS WARNING: Nineteen Eighty-Four will NOT enter the public domain in the United States of America until 2044 and in the European Union until 2020, although it is public domain in countries such as Canada, Russia, and Australia. (A list of free downloads appears under the external links section below.)

The following free online or downloadable editions of Nineteen Eighty-Four are available:

- (English)

- (French translation)

- (Russian translation)

- (Estonian translation)

- (Searchable etext)

- (Searchable online edition)

- (With publication data)

- (Project Gutenburg Australia e-text)

Other links:

- Students for an Orwellian Society (SOS)

- George Orwell Web Ring

- Orwelltoday.com — Comparing the world George Orwell described in "1984" with the world we are living in today

- Sinfest has several strips which are allusions to 1984; for instance, [7]

- An article on Nineteen Eighty-Four

- Big Brother Awards

- Privacy International

- The 1984 Index, which tracks the degree to which present conditions mirror those of the novel

- Flag-Burning: a Detriment to the Oceanian Way, a satire by Alexander S. Peak

- The Complete Newspeak Dictionary (newspeakdictionary.com)

- English Audio Book