Rune

- See Rune (disambiguation) for other uses.

The Runic alphabets are a set of related alphabets using letters known as runes, formerly used to write Germanic languages, mainly in Scandinavia and the British Isles, but before Christianization also on the European Continent. The Scandinavian variants are also known as Futhark (or fuþark, derived from their first six letters: F, U, Þ, A, R, and K); the Anglo-Saxon variant as Futhorc (due to sound changes undergone in Old English by the same six letters).

Overview

The earliest runic inscriptions date from ca. 150, and the alphabet was generally replaced by the Latin alphabet with Christianization, by ca. 700 in central Europe and by ca. 1400 in Scandinavia. However, the use of runes persisted for specialized purposes in Scandinavia, longest in rural Sweden until the early 20th century (used mainly for decoration as runes in Dalarna and on Runic calendars).

The three best known runic alphabets are:

- the Elder Futhark (ca. 150–800)

- the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc (400–1100)

- the Younger Futhark (800–1100)

The Younger Futhark is further divided into:

- the Danish futhark script

- the Swedish-Norwegian runic script (also: Short-twig or Rök Runes)

- the Hälsinge Runes (staveless runes)

The Younger Futhark developed further into:

- the Marcomannic Runes

- the Medieval Runes (1100-1500)

- the Dalecarlian Runes (ca. 1500–1800s)

The origins of the runic scripts are uncertain. Many characters of the elder futhark bear a close resemblance to characters from the latin alphabet. Other candidates are the 5th to 1st century BC Northern Italic alphabets, Lepontic, Rhaetic and Venetic, all closely related to each other and themselves descended from the Old Italic alphabet. These scripts bear a remarkable resemblance to the Futhark in many regards.

Background

The runes were introduced to, or invented by, the Germanic peoples in the 1st or 2nd century (The oldest known runic inscription dates to ca. the 160s and is found on a comb discovered in the bog of Vimose, Funen. The inscription reads harja). While at this time the Germanic language was certainly not at the Proto-Germanic stage any longer, it may still have been a continuum of dialects not yet clearly separated into the three branches of later centuries, viz. North Germanic, West Germanic and East Germanic. Most of the early runes from the Scandinavian countries are assumed to be in the Proto-Norse, the common ancestor language of the modern North Germanic languages. No distinction is made in surviving runic inscriptions between long and short vowels, although such a distinction was certainly present phonologically in the spoken languages of the time. Similarly, there are no signs for labiovelars in the Elder Futhark (such signs were introduced in both the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc and the Gothic alphabet as variants of p; see peorð.)

As Proto-Germanic evolved into its later language groups, the words assigned to the runes and the sounds represented by the runes themselves began to diverge somewhat, and each culture would either create new runes, rename or rearrange its rune names slightly, or even stop using obsolete runes completely, to accommodate these changes. Thus, the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc has several runes peculiar unto itself to represent diphthongs unique to (or at least prevalent in) the Anglo-Saxon dialect. However, the fact that the younger Futhark has sixteen runes, while the Elder Futhark has twenty four, is not fully explained by the some six hundred years of sound changes that had occurred in the North Germanic language group. The development here might seem rather astonishing, since the younger form of the alphabet came to use fewer different rune-signs at the same time as the development of the language led to a greater number of different phonemes than what had been present at the time of the older futhark. For example, voiced and unvoiced consonants merged in script, and so did many vowels, while the number of vowels in the spoken language increased. From about 1100, this disadvantage was eliminated in the medieval runes, which again increased the number of different signs to correspond with the number of phonemes in the language.

The name given to the signs, contrasting them with Latin or Greek letters, is attested on a 6th century alamannic runestaff as runa, and possibly as runo on the Einang stone (ca. 4th century). The name is from a root run- (Gothic runa) meaning "secret". (C.f. also Finnish, where runo was loaned to mean "poem".)

Origins

Mythological

In Norse mythology, the invention of runes is attributed to Odin: The Hávamál (stanzas 138, 139) describes how Odin receives the rune through his self-sacrifice. The text (in Old Norse and in English translation) is as follows:

| Veit ec at ec hecc vindga meiði a | I know that I hung on a windy tree |

| netr allar nío, | nights all nine, |

| geiri vndaþr oc gefinn Oðni, | wounded with a spear and given to Odin, |

| sialfr sialfom mer, | myself to myself, |

| a þeim meiþi, er mangi veit, hvers hann af rótom renn. | on that tree of which no man knows from where its roots run |

| Við hleifi mic seldo ne viþ hornigi, | No bread did they give me nor a drink from a horn, |

| nysta ec niþr, | downwards I peered, |

| nam ec vp rvnar, | I took up the runes, |

| opandi nam, | screaming I took them, |

| fell ec aptr þaðan. | then I fell back from there |

The Icelandic sources do not relate how the runes were transmitted to mortal men, but in 1555, the exiled Swedish archbishop Olaus Magnus recorded a tradition that a man named Kettil Runske had stolen three rune staffs from Odin and learned the runes and their magic.

Historical

The runes developed comparatively late, centuries after the Mediterranean alphabets from which they are probably descended. There are some similarities to alphabets of Phoenician origin (Latin, Greek, Italic) that cannot possibly all be due to chance; an Old Italic alphabet, more particularly the Raetic alphabet of Bozen-Bolzano, is usually quoted as a candidate for the origin of the runes, with only five Elder Futhark runes ( ᛖ e, ᛇ ï, ᛃ j, ᛜ ŋ, ᛈ p) having no counterpart in the Bolzano alphabet. This hypothesis is supported by the inscription on the Negau helmet dating to the 2nd century BC. This is in a northern Etruscan alphabet, but features a Germanic name, Harigast.

The angular shapes of the runes are shared with most contemporary alphabets of the period used for carving in wood or stone. A peculiarity of the runic alphabet as compared to the Old Italic family is rather the absence of horizontal strokes. Runes were commonly carved on the edge of narrow pieces of wood. The primary grooves cut spanned the whole piece vertically, against the grain of the wood: curves are difficult to make, and horizontal lines get lost among the grain of the split wood. This vertical characteristic also shared by other alphabets, such as the early form of the Latin alphabet used for the Duenos inscription.

The "West Germanic hypothesis" speculates on an introduction by West Germanic tribes. This hypothesis is based on claiming that the earliest inscriptions of ca. 200, found in bogs and graves around Jutland (the Vimose inscriptions), exhibit West Germanic name forms, e.g. wagnija, niþijo, and harija, and that these names refer to hitherto unknown tribes located in the Rhineland. However, Scandinavian scholars interprete these inscriptions as Proto-Norse, but it should be noted that the differences between Proto-Norse and other Germanic dialects were still minute and that the classification is mostly based on location rather than forms. Any claim that the forms refer to unknown tribes must be considered highly speculative. The genesis of the Elder Futhark was complete by the early 5th century, with the Kylver Stone being the first evidence of the futhark ordering as well as of the p rune.

Runes are a popular field for amateur scholars, and many imaginative ideas have been advanced, such as a claim by Olaus Rudbeck Sr in Atlantica that all writing systems originate from proto-runic scripts. Another fringe theory is that the runes originated directly from the Middle East, and are related to the Nabataean alphabet, a variant of the Phoenician alphabet. The introduction of runes is in this scenario ascribed to the Roman legions, which left Syria Palaestina during the 2nd century. This theory is based on discovery of early runes on weapons, such as longbows, and arrow heads, characteristically belonging to these soldiers. (The historical Nabataean kingdom, spanning Jordan, Sinai, and South Israel, corresponds to early Arabia.) This theory has not found main-stream support.

Magic and Divination

The earliest runic inscriptions were certainly not coherent texts of any length, but simple markings on artifacts (e.g. bracteates, combs, etc.), giving the name of either the craftsman or the proprietor, or, sometimes, remaining a linguistic mystery. Because of this, it is possible that the early runes were not so much used as a simple writing system, but rather as magical signs to be used for charms, or for divination. The name rune itself, taken to mean "secret, something hidden", seems to indicate that knowledge of the runes was originally considered esoteric, or restricted to an elite. The eerie 6th century Björketorp Runestone warns in Proto-Norse using the word rune in both senses:

- Haidz runo runu, falh'k hedra ginnarunaz. Argiu hermalausz, ... weladauþe, saz þat brytz. Uþarba spa.

- Here, I have hidden the secret of powerful runes, strong runes. The one who breaks this memorial will be eternally tormented by anger. Treacherous death will hit him. I foresee perdition.

The same curse and use of the word rune is also found on the Stentoften Runestone. There are also some inscriptions suggesting a medieval belief in the magical significance of runes, such as the Franks Casket (AD 700) panel.

However, it has proven difficult to find unambiguous traces of runic "oracles": Although Norse literature is full of references to runes, it nowhere contains specific instructions on divination or magic. There are at least three sources on divination with rather vague descriptions that may or may not refer to runes, Tacitus' Germania, Snorri Sturluson's Ynglinga saga and Rimbert's Vita Ansgari.

The first source, Tacitus' Germania, describes "signs" chosen in groups of three. A second source is the Ynglinga saga, where Granmar, the king of Södermanland, goes to Uppsala for the blót. There, the chips fell in a way that said that he would not live long (Féll honum þá svo spánn sem hann mundi eigi lengi lifa). The third source is Rimbert's Vita Ansgari, where there are three accounts of what seems to be the use of runes for divination, but Rimbert calls it "drawing lots". One of these accounts is the description of how a renegade Swedish king Anund Uppsale first brings a Danish fleet to Birka, but then changes his mind and asks the Danes to "draw lots". According to the story, this "drawing of lots" was quite informative, telling them that attacking Birka would bring bad luck and that they should attack a Slavic town instead.

The lack of knowledge on historical usage of the runes has not stopped modern authors from extrapolating entire systems of divination from what few specifics exist, usually loosely based on the runes' reconstructed names (see runic divination).

The mainstream view among scholars today is that the runes from the start were primarily a writing system, and that magic was not their primary function. However they could be, and were, still used for writing magic incantations, just like any other alphabet could.

Common use

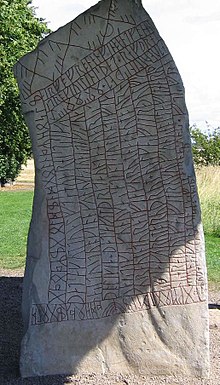

Some later runic finds are on monuments (rune stones), which often contain solemn inscriptions about people who died or performed great deeds. For a long time it was assumed that this kind of grand inscription was the primary use of runes, and that their use was associated with a certain societal class of rune-carvers.

However, in the middle of the 1950s, about 600 inscriptions known as the Bryggen inscriptions were found in Bergen. These inscriptions were made on wood and bone, often in the shape of sticks of various sizes, and contained inscriptions of an everyday nature - ranging from name tags, prayers (often in Latin), personal messages, business letters, expressions of affection, to bawdy phrases of a profane and sometimes even vulgar nature. Following this find, it is nowadays commonly assumed that at least in late use, Runic was a widespread and common writing system.

In the later Middle Ages, runes were also used in the Clog almanacs (sometimes called Runic staff, Prim or Scandinavian calendar) of Sweden. The authenticity of some monuments bearing Runic inscriptions found in Northern America is disputed, but most of them date from modern times.

Gothic runes

Theories of the existence of separate Gothic runes have been advanced, even identifying them as the original alphabet from which the Futhark were derived, but these have little support in actual findings (mainly the spearhead of Kovel, with its right-to-left inscription, its T-shaped tiwaz and its rectangular dagaz). If there ever were genuinely Gothic runes, they were soon replaced by the Gothic alphabet. The letters of the Gothic alphabet, however, as given by the Alcuin manuscript (9th century), are obviously related to the names of the Futhark. The names are clearly Gothic, but it is impossible to say whether they are as old as, or even older than, the letters themselves. A handful of Elder Futhark inscriptions were found in Gothic territory, such as the 4th century ring of Pietroassa.

Elder Fuþark

- Main article: Elder Futhark.

The Elder Futhark, used for writing proto-Norse (urnordisk, urnordiska), consist of twenty-four runes, often arranged in three rows of eight. The earliest known sequential listing of the full set of 24 runes dates to ca. 400 and is found on the Kylver Stone in Gotland.

The letter values, and their common transliteration are: ![]() [f],

[f], ![]() [u],

[u], ![]() [þ] ([th]),

[þ] ([th]), ![]() [a],

[a], ![]() [r],

[r], ![]() [k],

[k], ![]() [g],

[g], ![]() [w],

[w], ![]() [h],

[h], ![]() [n],

[n], ![]() [i],

[i], ![]() [j],

[j], ![]() [ï] ([ei]),

[ï] ([ei]), ![]() [p],

[p], ![]() [R],

[R], ![]() [s],

[s], ![]() [t],

[t], ![]() [b],

[b], ![]() [e],

[e], ![]() [m],

[m], ![]() [l],

[l], ![]() [ŋ] ([ng]),

[ŋ] ([ng]), ![]() [d],

[d], ![]() [o].

[o].

Names

Each rune most probably had a name, chosen to represent the sound of the rune itself. The names are, however, not directly attested for the Elder Futhark themselves. Reconstructed names in Proto-Germanic have been suggested for them, based on the names given for runes of the later alphabets in the rune poems and the names of the letters of the Gothic alphabet.

fehu "wealth, cattle"

fehu "wealth, cattle" ûruz "aurochs" (or ûram "water / slag"?)

ûruz "aurochs" (or ûram "water / slag"?) þurisaz "giant"

þurisaz "giant" ansuz "one of the Aesir" (or ahsam "ear (of corn)"?)

ansuz "one of the Aesir" (or ahsam "ear (of corn)"?) raidô "ride, journey"

raidô "ride, journey" kaunan "ulcer, illness"

kaunan "ulcer, illness" gebô "gift"

gebô "gift" wunjô "joy"

wunjô "joy" haglaz "hail (the precipitation)"

haglaz "hail (the precipitation)" naudiz "need"

naudiz "need" îsaz "ice"

îsaz "ice" jera "year"

jera "year" îhaz / îwaz "yew"

îhaz / îwaz "yew" perþô? "pearwood"? (uncertain)

perþô? "pearwood"? (uncertain) algiz "elk"? (uncertain)

algiz "elk"? (uncertain) sôwilô "Sun"

sôwilô "Sun" tîwaz (Tiwaz, the etymological continuant of *Dyeus)

tîwaz (Tiwaz, the etymological continuant of *Dyeus) berkanan "birch"

berkanan "birch" ehwaz "horse"

ehwaz "horse" mannaz "man"

mannaz "man" laguz "lake" (or laukaz "leek"?)

laguz "lake" (or laukaz "leek"?) ingwaz (a god)

ingwaz (a god) dagaz "day"

dagaz "day" ôþalan "estate, inheritance"

ôþalan "estate, inheritance"

Frisian and Anglo-Saxon Fuþorc

- Main article: Anglo-Saxon Futhorc.

The Futhorc are an extended alphabet, consisting of 29, and later even 33 characters. It was used probably from the 5th century onward. There are competing theories as to the origins of the Anglo-Saxon Fuþorc. One theory proposes that it was developed in Frisia and later spread to England. Another holds that runes were introduced by Scandinavians to England where the fuþorc was modified and exported to Frisia. Both theories have their inherent weaknesses and a definitive answer likely awaits more archaeological evidence. Futhorc inscriptions are found e.g. on the Thames scramasax, in the Vienna Codex, in CottonOtho B.x (Anglo-Saxon rune poem) and on the Ruthwell Cross.

The Anglo-Saxon rune poem has: ᚠ feoh, ᚢ ur, ᚦ thorn, ᚩ os, ᚱ rad, ᚳ cen, ᚷ gyfu, ᚹ wynn, ᚻ haegl, ᚾ nyd, ᛁ is, ᛄ ger, ᛇ eoh, ᛈ peordh, ᛉ eolh, ᛋ sigel, ᛏ tir, ᛒ beorc, ᛖ eh, ᛗ mann, ᛚ lagu, ᛝ ing, ᛟ ethel, ᛞ daeg, ᚪ ac, ᚫ aesc, ᚣ yr, ᛡ ior, ᛠ ear.

The expanded alphabet has the additional letters ᛢ cweorth, ᛣ calc, ᛤ cealc and ᛥ stan. It should be mentioned that these additional letters have only been found in manuscripts.

Feoh, þorn, and sigel stood for [f], [þ], and [s] in most environments, but voiced to [v], [ð], and [z] between vowels or voiced consonants. Gyfu and wynn stood for the letters yogh and wynn which became [g] and [w] in Middle English.

Younger Fuþark

The Younger Fuþark, also called Scandinavian Fuþark, is a reduced form of the Elder Futhark, consisting of only 16 characters. The reduction correlates with phonetic changes when Proto-Norse evolved into Old Norse. They are found in Scandinavia and Viking Age settlements abroad, probably in use from the 9th century onward. They are divided into long-branch (Danish) and short-twig (Swedish and Norwegian) runes. The difference between the two versions has been a matter of controversy. A general opinion is that the difference was functional, i.e. the long-branch runes were used for documentation on stone, whereas the short-branch runes were in every day use for private or official messages on wood.

Names

The Icelandic and Norwegian rune poems have 16 runes, with the letter names ᚠ fe ("wealth"), ᚢ ur ("iron"/"rain"), ᚦ Thurs, ᚬ As/Oss, ᚱ reidh ("ride"), ᚴ kaun ("ulcer"), ᚼ hagall ("hail"), ᚾ naudhr/naud ("need"), ᛁ is/iss ("ice"), ᛅ ar ("plenty"), ᛋ sol ("sun"), ᛏ Tyr, ᛒ bjarkan/bjarken ("birch"), ᛘ madhr/madr ("man"), ᛚ logr/lög ("water"), ᛦ yr ("yew").

Evolution

In the 7th century appeared an intermediary form of runes between the Elder Futhark and the Younger Futhark, but there are very few inscriptions. Two of them are the Stentoften Runestone and the Björketorp Runestone, where the haglaz rune ![]() has evolved into

has evolved into ![]() having the same form as the h-rune of the younger futhark, but it is used for an a-phoneme. The k-rune, which looks like a Y is a transition form between

having the same form as the h-rune of the younger futhark, but it is used for an a-phoneme. The k-rune, which looks like a Y is a transition form between ![]() and File:K-rune.gif in the two futharks.

and File:K-rune.gif in the two futharks.

The two futharks were in parallel use for some time, and one example of this is the Rök Runestone.

Long-branch runes

The long-branch runes are the following signs:

- ᚠ ᚢ ᚦ ᚬ ᚱ ᚴ ᚼ ᚾ ᛁ ᛅ ᛋ ᛏ ᛒ ᛘ ᛚ ᛦ

Short-twig runes

The short-twig runes (or Rök runes) are a simplified version of the long-branch runes, consisting of the following sixteen signs:

- ᚠ ᚢ ᚦ ᚭ ᚱ ᚴ ᚽ ᚿ ᛁ ᛆ ᛌ ᛐ ᛓ ᛙ ᛚ ᛧ

Hälsinge Runes (staveless runes)

Hälsinge runes are found in the Hälsingland region of Sweden, used between the 10th and 12th centuries. The runes seem to be a simplification of the Swedish–Norwegian runes and lack vertical strokes, hence the name 'staveless.' They cover the same set of letters as the other Younger Futhark alphabets. This variant has no assigned Unicode range (as of Unicode 4.0).

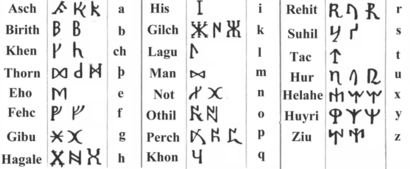

"Marcomannic runes"

In a treatise called de inventione litterarum, preserved in 8th and 9th century manuscripts, mainly from the southern part of the Carolingian Empire (Alemannia, Bavaria), ascribed to Hrabanus Maurus, a runic alphabet consisting of a curious mixture of Elder Futhark with Anglo-Saxon Futhorc is recorded. The alphabet is traditionally called "Marcomannic runes", but it has no connection with the Marcomanni and is rather an attempt of Carolingian scholars to represent all letters of the Latin alphabets with runic equivalents.

Medieval Runes

In the middle ages, the younger futhark in Scandinavia was expanded, so that it once more contained one sign for each phoneme of the old norse language. Dotted variants of voiceless signs were introduced to denote the corresponding voiced consonants, or vice versa, voiceless variants of voiced consonants, and several new runes also appeared for vowel sounds. Inscriptions in medieval Scandanavian runes show a large number of variant rune-forms, and some letters, such as s, c and z, were often used interchangeably.(Jacobsen & Moltke, 1941-42, p. VII)(Werner, 2004, p. 20)

Medieval runes were in use until the 15th century. Of the total number of Norwegian runic inscriptions preserved today, most are medieval runes. Notably, more than 600 inscriptions using these runes have been discovered in Bergen since the 1950s, mostly on wooden sticks (the so-called Bryggen inscriptions). This indicates that runes were in common use side by side with the latin alphabet for several centuries. Indeed some of the medieval runic inscriptions are actually in latin language.

Dalecarlian Runes

According to Carl-Gustav Werner, "in the isolated province of Dalarna in Sweden a mix of runes and Latin letters developed."(Werner 2004, p. 7) The Dalecarlian runes came into use in the early 16th century and remained in some use up to the 20th century. Some discussion remains on whether their use was an unbroken tradition throughout this period or whether people in the 19th and 20th centuries learned runes from books written on the subject. The character inventory was mainly used for transcribing Älvdalen speech.

Modern use

Third Reich

Runes have been used in Nazi symbolism by Nazis and neo-Nazi groups that associate themselves with Germanic traditions, mainly the Sigel, Eihwaz, Tyr, Odal (see Odalism) and Algiz runes.

The fascination that runes seem to have exerted on the Nazis can be traced to the occult and völkisch author Guido von List, one of the important figures in Germanic mysticism and runic revivalism in the late 19th and early 20th century. In 1908, List published in Das Geheimnis der Runen ("The Secret of the Runes") a set of 18 so-called "Armanen Runes", based on the Younger Futhark, which were allegedly revealed to him in a state of temporary blindness after a cataract operation on both eyes in 1902.

In Nazi contexts, the s-rune is referred to as "Sig" (after List, probably from Anglo-Saxon Sigel). The "Wolfsangel", while not a rune historically, has the shape of List's "Gibor" rune.

Neopaganism

The runes are a major element in Germanic neopaganism, often used to indicate ancestry, aesthetically in crafts and for ritual purposes. New Agers and Wiccans may also sometimes use runes under various conditions, such as divination.

Modern popular culture

Historical and fictional runes appear commonly in modern popular culture, particularly in fantasy literature, video games and various other forms of media.

Unicode

Runic alphabets are assigned Unicode range 16A0–16FF. This block is intended to encode all shapes of runic letters. Each letter is encoded only once, regardless of the number of alphabets in which it occurs.

The block contains 81 symbols: 75 runic letters (16A0–16EA), three punctuation marks (Runic Single Punctuation 16EB ᛫, Runic Multiple Punctuation 16EC ᛬ and Runic Cross Punctuation 16ED ᛭), and three runic symbols that are used in mediaeval calendar staves ("Golden number Runes", Runic Arlaug Symbol 16EE ᛮ, Runic Tvimadur Symbol 16EF ᛯ and Runic Belgthor Symbol 16F0 ᛰ). Characters 16F1–16FF are presently (as of Unicode Version 4.1) unassigned.

Table of runic letters (U+16A0–U+16EA):

| 16A0 | ᚠ | fehu feoh fe f | 16B0 | ᚰ | on | 16C0 | ᛀ | dotted-n | 16D0 | ᛐ | short-twig-tyr t | 16E0 | ᛠ | ear |

| 16A1 | ᚡ | v | 16B1 | ᚱ | raido rad reid r | 16C1 | ᛁ | isaz is iss i | 16D1 | ᛑ | d | 16E1 | ᛡ | ior |

| 16A2 | ᚢ | uruz ur u | 16B2 | ᚲ | kauna | 16C2 | ᛂ | e | 16D2 | ᛒ | berkanan beorc bjarkan b | 16E2 | ᛢ | cweorth |

| 16A3 | ᚣ | yr | 16B3 | ᚳ | cen | 16C3 | ᛃ | jeran j | 16D3 | ᛓ | short-twig-bjarkan b | 16E3 | ᛣ | calc |

| 16A4 | ᚤ | y | 16B4 | ᚴ | kaun k | 16C4 | ᛄ | ger | 16D4 | ᛔ | dotted-p | 16E4 | ᛤ | cealc |

| 16A5 | ᚥ | w | 16B5 | ᚵ | g | 16C5 | ᛅ | long-branch-ar ae | 16D5 | ᛕ | open-p | 16E5 | ᛥ | stan |

| 16A6 | ᚦ | thurisaz thurs thorn | 16B6 | ᚶ | eng | 16C6 | ᛆ | short-twig-ar a | 16D6 | ᛖ | ehwaz eh e | 16E6 | ᛦ | long-branch-yr |

| 16A7 | ᚧ | eth | 16B7 | ᚷ | gebo gyfu g | 16C7 | ᛇ | iwaz eoh | 16D7 | ᛗ | mannaz man m | 16E7 | ᛧ | short-twig-yr |

| 16A8 | ᚨ | ansuz a | 16B8 | ᚸ | gar | 16C8 | ᛈ | pertho peorth p | 16D8 | ᛘ | long-branch-madr m | 16E8 | ᛨ | icelandic-yr |

| 16A9 | ᚩ | os o | 16B9 | ᚹ | wunjo wynn w | 16C9 | ᛉ | algiz eolhx | 16D9 | ᛙ | short-twig-madr m | 16E9 | ᛩ | q |

| 16AA | ᚪ | ac a | 16BA | ᚺ | haglaz h | 16CA | ᛊ | sowilo s | 16DA | ᛚ | laukaz lagu logr l | 16EA | ᛪ | x |

| 16AB | ᚫ | aesc | 16BB | ᚻ | haegl h | 16CB | ᛋ | sigel long-branch-sol s | 16DB | ᛛ | dotted-l | |||

| 16AC | ᚬ | long-branch-oss o | 16BC | ᚼ | long-branch-hagall h | 16CC | ᛌ | short-twig-sol s | 16DC | ᛜ | ingwaz | |||

| 16AD | ᚭ | short-twig-oss o | 16BD | ᚽ | short-twig-hagall h | 16CD | ᛍ | c | 16DD | ᛝ | ing | |||

| 16AE | ᚮ | o | 16BE | ᚾ | naudiz nyd naud n | 16CE | ᛎ | z | 16DE | ᛞ | dagaz daeg d | |||

| 16AF | ᚯ | oe | 16BF | ᚿ | short-twig-naud n | 16CF | ᛏ | tiwaz tir tyr t | 16DF | ᛟ | othalan ethel o |

Corpus

The largest group of surviving Runic inscription are Viking Age Younger Futhark runestones, most commonly found in Sweden. Another large group are medieval runes, most commonly found on small objects, often wooden sticks. The largest concentration of runic inscriptions are the Bryggen inscriptions found in Bergen, more than 650 in total. Elder Futhark inscriptions number around 350 , about 260 of which are from Scandinavia, of which about half are on bracteates. Anglo-Saxon Futhorc-inscriptions number around 100 items.

The following table lists the number of known inscriptions (in any alphabet variant) by geographical region[citation needed]:

| Area | number of rune inscriptions |

|---|---|

| Sweden | 3432 |

| Norway | 1552 |

| Denmark | 844 |

| Scandinavian total | 5826 |

| Continental Europe except Scandinavia and Frisia | 80 |

| Frisia | 20 |

| The British Isles except Ireland | > 200 |

| Greenland | > 100 |

| Iceland | < 100 |

| Ireland | 16 |

| Faroes | 9 |

| Non-Scandinavian total | > 500 |

| Total | > 6400 |

"Runiform" scripts

The 8th century Orkhon script (sometimes called Old Turkic), and the related medieval Old Hungarian script are often called runes, but strictly speaking that term refers only to the Germanic alphabet. For this reason, they are also sometimes referred to as "runiform".

See also

- Elder Futhark

- Rune poem

- Rune stone

- Solomon and Saturn

- Codex Runicus

- Siglas Poveiras

- Computus Runicus

- Old Italic alphabet

- Ogham, the early Irish monumental alphabet

- the "Armanen runes", invented by Guido von List

- the Cirth "runes", invented by J.R.R. Tolkien

- Runic divination

References

- Brate, Erik (1922). Sveriges runinskrifter, (online text in Swedish)

- Düwel, Klaus (2001). Runenkunde, Verlag J.B. Metzler (In German).

- Jacobsen, Lis (1941–42). Danmarks runeindskrifter. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaards Forlag.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - Looijenga, J. H. (1997). Runes around the North Sea and on the Continent AD 150-700, dissertation, Groningen University.

- Page, R.I. (1999). An Introduction to English Runes, The Boydell Press, Woodbridge. ISBN 085115946x.

- Robinson, Orrin W. (1992). Old English and its Closest Relatives: A Survey of the Earliest Germanic Languages Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804714541

- Spurkland, Terje (2005). Norwegian Runes and Runic Inscriptions", Boydell Press. ISBN 1843831864

- Werner, Carl-Gustav (2004). The allrunes Font and Package[1].

External links

- the Futhark (ancientscripts.com)

- Omniglot Rune Page

- The Development of Old Germanic Alphabets

- 'An Introduction to the Visionary Alphabet of the Northern World'

(titus.uni-frankfurt.de, with an image of the Negau helmet)

- Encoding

- Code2000 shareware Unicode font by James Kass

- Friskfonter 1.0 - a compilation of Runic and Gothic fonts (freeware)

- Unicode Code Chart (PDF)

- Divination

- Meaning of the Runes

- Runes Index (inthestars.co.uk)