Lower Manhattan

Lower Manhattan, also known as Downtown Manhattan, is the southernmost part of Manhattan, the central borough for business, culture, and government in the City of New York, which itself originated at the southern tip of Manhattan Island in 1624.[1]

Geography

Lower Manhattan is defined most commonly as the area delineated on the north by 14th Street, on the west by the Hudson River, on the east by the East River, and on the south by New York Harbor (also known as Upper New York Bay). When referring specifically to the Lower Manhattan business district and its immediate environs, the northern border is commonly designated by thoroughfares approximately a mile-and-a-half south of 14th Street and a mile north of the island's southern tip: Chambers Street from near the Hudson east to the Brooklyn Bridge entrances and overpass. Two other major arteries are also sometimes identified as the northern border of "Lower" or "Downtown Manhattan": Canal Street, roughly half a mile north of Chambers Street, and 23rd Street, roughly half a mile north of 14th Street.

The Lower Manhattan business district forms the core of the area below Chambers Street. It includes the Financial District (often referred to as Wall Street, after its primary artery) and the World Trade Center site. At the island's southern tip is Battery Park; City Hall is just to the north of the Financial District. Also south of Chambers Street are the planned community of Battery Park City and the South Street Seaport historic area. The neighborhood of TriBeCa straddles Chambers on the west side; at the street's east end is the giant Manhattan Municipal Building. North of Chambers Street and the Brooklyn Bridge and south of Canal Street lies most of New York's oldest Chinatown neighborhood. Many court buildings and other government offices are also located in this area. The Lower East Side neighborhood straddles Canal. North of Canal Street and south of 14th Street are the neighborhoods of SoHo, the Meatpacking District, the West Village, Greenwich Village, Little Italy, Nolita, and the East Village. Between 14th and 23rd streets are lower Chelsea, Union Square, the Flatiron District, Gramercy, and the large residential development Peter Cooper Village—Stuyvesant Town in the eastern part.

History

Lenape and New Netherland

The area that would eventually encompass modern day New York City was inhabited by the Lenape people. These groups of culturally and linguistically identical Native Americans traditionally spoke an Algonquian language now referred to as Unami.

European settlement began with the founding of a Dutch fur trading post in Lower Manhattan, later called New Amsterdam (Template:Lang-nl) in 1626.[2][3] The first fort was built at the Battery to protect New Netherland.[4]

Soon thereafter, most likely in 1626, construction of Fort Amsterdam began.[4] Later, the Dutch West Indies Company imported African slaves to serve as laborers; they helped to build the wall that defended the town against English and Indian attacks. Early directors included Willem Verhulst and Peter Minuit. Willem Kieft became director in 1638 but five years later was embroiled in Kieft's War against the Native Americans. The Pavonia Massacre, across the Hudson River in present-day Jersey City resulted in the death of 80 natives in February 1643. Following the massacre, Algonquian tribes joined forces and nearly defeated the Dutch. The Dutch Republic sent additional forces to the aid of Kieft, leading to the overwhelming defeat of the Native Americans and a peace treaty on August 29, 1645.[5]

On May 27, 1647, Peter Stuyvesant was inaugurated as director general upon his arrival. The colony was granted self-government in 1652, and New Amsterdam was formally incorporated as a city on February 2, 1653.[6] The first mayors (burgemeesters) of New Amsterdam, Arent van Hattem and Martin Cregier, were appointed in that year.[7]

17th and 18th centuries

In 1664, the English conquered the area and renamed it "New York" after the Duke of York.[8] At that time, people of African descent made up 20% of the population of the city, with European settlers numbering approximately 1,500,[9] and people of African descent numbering 375 (with 300 of that 375 enslaved and 75 free).[10] (Though it has been claimed that African slaves comprised 40% of the small population of the city at that time,[11] this claim has not been substantiated.) During the mid 1600s, farms of free blacks covered 130 acres (53 ha) where Washington Square Park later developed.[12] The Dutch briefly regained the city in 1673, renaming the city "New Orange", before permanently ceding the colony of New Netherland to the English for what is now Suriname in November 1674.

The new English rulers of the formerly Dutch New Amsterdam and New Netherland renamed the settlement New York. As the colony grew and prospered, sentiment also grew for greater autonomy. In the context of the Glorious Revolution in England, Jacob Leisler led Leisler's Rebellion and effectively controlled the city and surrounding areas from 1689–1691, before being arrested and executed.

By 1700, the Lenape population of New York had diminished to 200.[13] By 1703, 42% of households in New York had slaves, a higher percentage than in Philadelphia or Boston.[14]

The 1735 libel trial of John Peter Zenger in the city was a seminal influence on freedom of the press in North America. It would be a standard for the basic articles of freedom in the United States Declaration of Independence.

By the 1740s, with expansion of settlers, 20% of the population of New York were slaves, totaling about 2,500 people.[15] After a series of fires in 1741, the city became panicked that blacks planned to burn the city in a conspiracy with some poor whites. Historians believe their alarm was mostly fabrication and fear, but officials rounded up 31 blacks and 4 whites, all of whom were convicted of arson and executed. City officials executed 13 blacks by burning them alive and hanged 4 whites and 18 blacks.[16]

In 1754, Columbia University was founded under charter by George II of Great Britain as King's College in Lower Manhattan.[17]

The Stamp Act and other British measures fomented dissent, particularly among the Sons of Liberty, who maintained a long-running skirmish with locally stationed British troops over Liberty Poles from 1766 to 1776. The Stamp Act Congress met in New York City in 1765 in the first organized resistance to British authority across the colonies. After the major defeat of the Continental Army in the Battle of Long Island, General George Washington withdrew to Manhattan Island, but with the subsequent defeat at the Battle of Fort Washington the island was effectively left to the British. The city became a haven for loyalist refugees, becoming a British stronghold for the entire war. Consequently, the area also became the focal point for Washington's espionage and intelligence-gathering throughout the war.

In 1771, Bear Market was established along the Hudson shore on land donated by Trinity Church, and replaced by Washington Market in 1813.[18]

New York City was greatly damaged twice by fires of suspicious origin during British military rule. The city became the political and military center of operations for the British in North America for the remainder of the war and a haven for Loyalist refugees. Continental Army officer Nathan Hale was hanged in Manhattan for espionage. In addition, the British began to hold the majority of captured American prisoners of war aboard prison ships in Wallabout Bay, across the East River in Brooklyn. More Americans lost their lives from neglect aboard these ships than died in all the battles of the war. British occupation lasted until November 25, 1783. George Washington triumphantly returned to the city that day, as the last British forces left the city.

Starting in 1785, the Congress met in New York City under the Articles of Confederation. In 1789, New York City became the first national capital of the United States under the new United States Constitution. The Constitution also created the current Congress of the United States, and its first sitting was at Federal Hall on Wall Street. The first United States Supreme Court sat there. The United States Bill of Rights was drafted and ratified there. George Washington was inaugurated at Federal Hall.[19] New York City remained the capital of the U.S. until 1790, when the role was transferred to Philadelphia.

19th century

New York grew as an economic center, first as a result of Alexander Hamilton's policies and practices as the first Secretary of the Treasury and, later, with the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, which connected the Atlantic port to the vast agricultural markets of the North American interior.[20][21] Immigration resumed after being slowed by wars in Europe, and a new street grid system, the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, expanded to encompass all of Manhattan. Early in the 19th century, landfill was used to expand Lower Manhattan from the natural Hudson shoreline at Greenwich Street to West Street.[22]

In 1898, the modern City of New York was formed with the consolidation of Brooklyn (until then an independent city), Manhattan and outlying areas.[23] The borough of Brooklyn incorporated the independent City of Brooklyn, recently joined to Manhattan by the Brooklyn Bridge in Lower Manhattan. Municipal governments contained within the boroughs were abolished, and the county governmental functions, housed in Lower Manhattan after unification, were absorbed by the City or each borough.[24]

20th century

Washington Market was located between Barclay and Hubert Streets, and from Greenwich Street to West Street.[25] It was demolished in the 1960s and replaced by a new Independence Plaza, Washington Market Park and other developments.

Lower Manhattan retains one of the most irregular street grid plans in the borough. Throughout the early decades of the 1900s, the area experienced a construction boom, with major towers such as 40 Wall Street, the American International Building, Woolworth Building, and 20 Exchange Place being erected.

On March 25, 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in Greenwich Village took the lives of 146 garment workers, which would eventually lead to great advancements in the city's fire department, building codes, and workplace regulations.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the city became a world center for industry, commerce, and communication. Interborough Rapid Transit (the first New York City Subway company) began operating in 1904. The area's demographics stabilized, labor unionization brought new protections and affluence to the working class, the city's government and infrastructure underwent a dramatic overhaul under Fiorello La Guardia, and his controversial parks commissioner, Robert Moses, ended the blight of many tenement areas, expanded new parks, remade streets, and restricted and reorganized zoning controls, especially in Lower Manhattan.

In the 1950s, a few new buildings were constructed in lower Manhattan, including an 11-story building at 156 William Street in 1955.[26] A 27-story office building at 20 Broad Street, a 12-story building at 80 Pine Street, a 26-story building at 123 William Street, and a few others were built in 1957.[26] By the end of the decade, lower Manhattan had become economically depressed, in comparison with midtown Manhattan, which was booming. David Rockefeller spearheaded widespread urban renewal efforts in lower Manhattan, beginning with construction One Chase Manhattan Plaza, the new headquarters for his bank. He established the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association (DLMA) which drew up plans for broader revitalization of lower Manhattan, with the development of a world trade center at the heart of these plans. The original DLMA plans called for the "world trade center" to be built along the East River, between Old Slip and Fulton Street. After negotiations with New Jersey Governor Richard J. Hughes, the Port Authority decided to build the World Trade Center on a site along the Hudson River and the West Side Highway, rather than the East River site.[citation needed]

Through much of its history, the area south of Chambers Street was mainly a commercial district, with a small population of residents—in 1960, it was home to about 4,000.[27] Construction of Battery Park City, on landfill from construction of the World Trade Center, brought many new residents to the area. Gateway Plaza, the first Battery Park City development, was finished in 1983. The project's centerpiece, the World Financial Center, consists of four luxury highrise towers. By the turn of the century, Battery Park City was mostly completed, with the exception of some ongoing construction on West Street. Around this time, lower Manhattan reached its highest population of business tenants and full-time residents.[citation needed]

When building the World Trade Center, 1.2 million cubic yards (917,000 m³) of material was excavated from the site.[28] Rather than dumping the spoil at sea or in landfills, the fill material was used to expand the Manhattan shoreline across West Street, creating Battery Park City.[29] The result was a 700-foot (210-m) extension into the river, running six blocks or 1,484 feet (452 m), covering 92 acres (37 ha), providing a 1.2-mile (1.9 km) riverfront esplanade and over 30 acres (12 ha) of parks.[30]

In 1968, the Stonewall riots were a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations by members of the gay community against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village.[clarification needed] They are widely considered to constitute the single most important event leading to the gay liberation movement and the modern fight for LGBT rights in the United States.[33][34]

Since the early twentieth century, Lower Manhattan has been an important center for the arts and leisure activities. Greenwich Village was a locus of bohemian culture from the first decade of the century through the 1980s. Several of the city's leading jazz clubs are still located in Greenwich Village, which was also one of the primary bases of the American folk music revival of the 1960s. Many art galleries were located in SoHo between the 1970s and early 1990s; today, the downtown Manhattan gallery scene is centered in Chelsea. From the 1960s onward, lower Manhattan has been home to many alternative theater companies, constituting the heart of the Off-Off-Broadway community. Punk rock and its derivatives emerged in the mid-1970s largely at two venues: CBGB on the Bowery, the western edge of the East Village, and Max's Kansas City on Park Avenue South. At the same time, the area's surfeit of reappropriated industrial lofts played an integral role in the development and sustenance of the minimalist composition, free jazz, and disco/electronic dance music subcultures. The area's many nightclubs and bars—though mostly shorn of the freewheeling iconoclasm, pioneering spirit, and do-it-yourself mentality that characterized the pre-gentrification era—still draw patrons from throughout the city and the surrounding region. In the early twenty-first century, the Meatpacking District, once the sparsely populated province of after-hours BDSM clubs and transgender prostitutes, gained a reputation as New York's trendiest neighborhood.[35]

21st century

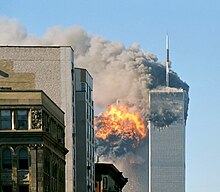

On September 11, 2001, two of four hijacked planes were flown into the Twin Towers of the original World Trade Center, and the towers collapsed. The 7 World Trade Center was not struck by a plane, but collapsed because of heavy debris falling from the impacts of planes and the collapse of the North Tower. The other buildings of the World Trade Center complex were damaged beyond repair and soon after demolished. The collapse of the Twin Towers caused extensive damage to surrounding buildings and skyscrapers in Lower Manhattan, and resulted in the deaths of 2,606 people, in addition to those on the planes. Since September 11, Lower Manhattan lost much of its economy and office space,[36] but most of Lower Manhattan has been restored. However, many rescue workers and residents of the area developed several life-threatening illnesses and some have already died.[37] The area's economy has rebounded significantly since then. The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation has consummated plans to rebuild downtown Manhattan by adding new streets, buildings, and office space. The National September 11 Memorial at the site was opened to the public on September 11, 2011, while the National September 11 Museum was officially inaugurated by President Barack Obama on May 15, 2014.[38] As of the time of its opening in November 2014, the new One World Trade Center, formerly known as the Freedom Tower, is the tallest skyscraper in the Western Hemisphere[39] and the fourth-tallest in the world, at 1,776 feet;[40] while other skyscrapers are under construction at the site.

The Occupy Wall Street protests in Zuccotti Park, formerly known as Liberty Plaza Park, began in the Financial District on September 17, 2011, receiving global attention and spawning the Occupy movement against social and economic inequality worldwide.[41]

On October 29 and 30, 2012, Hurricane Sandy ravaged portions of Lower Manhattan with record-high storm surge from New York Harbor, severe flooding, and high winds, causing power outages for hundreds of thousands of Manhattanites and leading to gasoline shortages and disruption of mass transit systems. The storm and its effects have prompted the discussion of constructing seawalls and other coastal barriers around the shorelines of Manhattan and the New York City metropolitan region to minimize the risk of destructive consequences from another such event in the future.[42]

Lower Manhattan has been experiencing a baby boom, well above the overall birth rate in Manhattan, with the area south of Canal Street witnessing 1,086 births in 2010, 12% greater than 2009 and over twice the number born in 2001.[43] The Financial District alone has witnessed growth in its population to approximately 43,000 as of 2014, nearly double the 23,000 recorded at the 2000 Census.[44] The southern tip of Manhattan became the fastest growing part of New York City between 1990 and 2014.[45]

In June 2015, The New York Times wrote that Lower Manhattan's dining scene was experiencing a renaissance.[46]

Historical sites

Perhaps Lower Manhattan's most renowned landmark is now the former World Trade Center site. Before the September 11 attacks, the Twin Towers were iconic of Lower Manhattan's global significance as a financial center. The new office towers (including One World Trade Center) are expected to restore the Lower Manhattan skyline and give it the title of the fourth largest central business district in the United States, behind Midtown Manhattan and the Chicago Loop. The 9/11 Memorial has become a popular draw for visitors.

The area contains many historical buildings and sites, including Castle Garden, originally the fort Castle Clinton, Bowling Green, the old United States Customs House, now the National Museum of the American Indian, Federal Hall, where George Washington was inaugurated as the first U.S. President, Fraunces Tavern, New York City Hall,the Museum of American Finance, the New York Stock Exchange, renovated original mercantile buildings of the South Street Seaport (and a modern tourist building), the Brooklyn Bridge, South Ferry, embarkation point for the Staten Island Ferry and ferries to Liberty Island and Ellis Island, and Trinity Church. Lower Manhattan is home to some of New York City's most spectacular skyscrapers, including the Woolworth Building, 40 Wall Street (also known as the Trump Building), the Standard Oil Building at 26 Broadway, and the American International Building.

Among the commercial districts of Lower Manhattan no longer in existence was Radio Row on Cortlandt Street, which was demolished in 1966 to make way for construction of the former World Trade Center.

Denotation

Downtown in the context of Manhattan, and of New York City generally, has different meanings to different people, especially depending on where in the city they reside. Residents of the island or of The Bronx generally speak of going "downtown" to refer to any southbound excursion to any Manhattan destination.[50] A declaration that one is going to be "downtown" may indicate a plan to be anywhere south of 14th Street—the definition of downtown according to the city's official tourism marketing organization[50]—or even 23rd Street.[51] The full phrase Downtown Manhattan may also refer more specifically to the area of Manhattan south of Canal Street.[27] Within business-related contexts, many people use the term Downtown Manhattan to refer only to the Financial District and the corporate offices in the immediate vicinity. For instance, the Business Improvement District managed by the Alliance for Downtown New York defines Downtown as South of Murray Street (essentially South of New York City Hall), which includes the World Trade Center area and the Financial District. The phrase Lower Manhattan may apply to any of these definitions: the broader ones often if the speaker is discussing the area in relation to the rest of the city; more restrictive ones, again, if the focus is on business matters or on the early colonial and post-colonial history of the island.[citation needed]

As reflected in popular culture, "Downtown" in Manhattan has historically represented a place where one could "forget all your troubles, forget all your cares, and go Downtown," as the lyrics of Petula Clark's 1964 hit "Downtown" celebrate (although Tony Hatch, the songwriter of the track, later clarified that he naively believed Times Square to be "downtown," and was the actual inspiration for the hit single). The protagonist of Billy Joel's 1983 hit "Uptown Girl" contrasts himself (a "downtown man") with the purportedly staid uptown world.[52] Likewise, the chorus of Neil Young's 1995 single "Downtown" urges "Let's have a party, downtown all right."

Economy

Before the completion of One World Trade Center, Lower Manhattan was the fourth largest business district in the United States, after Midtown Manhattan, the Chicago Loop, and Washington, D.C.; Lower Manhattan is now the fourth largest central business district in the U.S.[53] Anchored by Wall Street, New York City functions as the financial capital of the world and has been called the world's most economically powerful city.[54][55][56][57][58] Lower Manhattan is home to the New York Stock Exchange, on Wall Street, and the corporate headquarters of NASDAQ, at 165 Broadway, representing the world's largest and second largest stock exchanges, respectively, when measured both by overall average daily trading volume and by total market capitalization of their listed companies in 2013.[47] Wall Street investment banking fees in 2012 totaled approximately US$40 billion.[59]

Other large companies with headquarters in Lower Manhattan include, in alphabetical order:

- Ambac Financial Group[60]

- AOL, at 770 Broadway[61] At the investment banking company

- EmblemHealth and Standard & Poor's, at 55 Water Street[62][63] HIP Health Plan of New York, which became a part of EmblemHealth, moved there with 2,000 employees in October 2004. It was the largest corporate relocation in downtown Manhattan following the September 11 attacks.[64]

- Goldman Sachs, at 200 West Street

- IBT Media, publisher of the International Business Times and Newsweek, among other publications; located in Hanover Square

- Nielsen Company and subsidiary Nielsen Media Research[65][66]

- PR Newswire, at 350 Hudson Street.[67]

- Verizon Communications, at 140 West Street.[68]

Prior to the September 11 attacks, One World Trade Center served as the headquarters of Cantor Fitzgerald.[69] Prior to its dissolution, the headquarters of US Helicopter were in Lower Manhattan.[70] When Hi Tech Expressions existed, its headquarters were in Lower Manhattan.[71][72]

Government and infrastructure

The headquarters of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey is located in Four World Trade Center of the World Trade Center complex.[73]

The city hall and related government infrastructure of the City of New York are located in Lower Manhattan, next to City Hall Park. The Jacob K. Javits Federal Building is located in Civic Center. It includes the Federal Bureau of Investigation New York field office.[74]

Many New York City Subway lines converge downtown. The largest hub, the Fulton Center, re-opened in 2014 after a $1.4 billion reconstruction project necessitated by the September 11, 2001 attacks. This transit hub linking nine existing subway lines was expected to serve 300,000 daily riders.[75] The World Trade Center Transportation Hub and PATH station opened in 2016.[76] Ferry services are also concentrated downtown.

See also

References

- ^ "Manhattan, New York – Some of the Most Expensive Real Estate in the World Overlooks Central Park". The Pinnacle List. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ "United States History – History of New York City, New York". Online Highways LLC. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ Rankin, Rebecca B., Cleveland Rodgers (1948). New York: the World's Capital City, Its Development and Contributions to Progress. Harper.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b ""Battery Park". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved on September 13, 2008". Nycgovparks.org. Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ^ Ellis, Edward Robb (1966). The Epic of New York City. Old Town Books. pp. 37–40.

- ^ Ellis, Edward Robb (1966). The Epic of New York City. Old Town Books. p. 57.

- ^ Scheltema, Gajus and Westerhuijs, Heleen (eds.),Exploring Historic Dutch New York. Museum of the City of New York/Dover Publications, New York 2011.

- ^ Homberger, Eric (2005). The Historical Atlas of New York City: A Visual Celebration of 400 Years of New York City's History. Owl Books. p. 34. ISBN 0-8050-7842-8.

- ^ Harris, Leslie M. (2003). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. The University of Chicago Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0226317731.

- ^ Harris, Leslie M. (2003). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. The University of Chicago Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0226317731.

- ^ Spencer P.M. Harrington, "Bones and Bureaucrats", Archeology, March/April 1993, accessed 11 February 2012

- ^ Rothstein, Edward (26 February 2010). "A Burial Ground and Its Dead Are Given Life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gotham Center for New York City History" Timeline 1700–1800

- ^ "The Hidden History of Slavery in New York". The Nation. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ^ Rothstein, Edward (26 February 2010). "A Burial Ground and Its Dead Are Given Life". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1972). The Oxford History of the American People. New York City: Mentor. p. 207. ISBN 0-451-62600-1.

- ^ Moore, Nathaniel Fish (1876). An Historical Sketch of Columbia College, in the City of New York, 1754–1876. Columbia College. p. 8.

- ^ "A Public Market for Lower Manhattan" (PDF). New York City Council.

- ^ "The People's Vote: President George Washington's First Inaugural Speech (1789)". U.S. News and World Report. Archived from the original on 2008-09-25. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bridges, William (1811). Map of the City of New York and Island of Manhattan with Explanatory Remarks and References.

- ^ Lankevich (1998), pp. 67–68.

- ^ Cudahy, Brian J. Cudahy (1990). Over and Back: The History of Ferryboats in New York Harbor. Fordham University Press. p. 25. ISBN 0-8232-1245-9.

- ^ The 100 Year Anniversary of the Consolidation of the 5 Boroughs into New York City, New York City. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth (1995). Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 206. "[B]orough presidents ... responsible for local administration and public works."

- ^ Millstein, Gilbert (April 24, 1960). "Restless Ports for the City's Food". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Bartnett, Edmond J. (December 25, 1960). "Building Activity Soars Downtown". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Brown, Charles H. (January 31, 1960). "'Downtown' Enters a New Era". The New York Times.

- ^ Gillespie, Angus K. (1999). Twin Towers: The Life of New York City's World Trade Center. Rutgers University Press. p. 71. ISBN 0-7838-9785-5.

- ^ Iglauer, Edith (November 4, 1972). "The Biggest Foundation". The New Yorker.

- ^ ASLA 2003 The Landmark Award, American Society of Landscape Architects. Accessed May 17, 2007.

- ^ "Workforce Diversity The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ Eli Rosenberg (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ National Park Service (2008). "Workforce Diversity: The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". US Department of Interior. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ "Obama inaugural speech references Stonewall gay-rights riots". North Jersey Media Group. January 21, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ Steinberg, Jon (2004-08-18). "Meatpacking District Walking Tour". New York. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ^ "Measuring the Effects of the September 11 Attack on New York City" (PDF). http://newyorkfed.org/. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Edelman, Susan (January 6, 2008). "Charting post-9/11 deaths". Retrieved January 22, 2012.

- ^ "Long delayed Sept 11 Memorial Museum inaugurated by Obama". Mainstream Media EC. May 15, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ DeGregory, Priscilla (November 3, 2014). "1 World Trade Center is open for business". New York Post. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ Katia Hetter (November 12, 2013). "It's official: One World Trade Center to be tallest U.S. skyscraper". CNN. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ^ "OccupyWallStreet - About". The Occupy Solidarity Network, Inc. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ Robert S. Eshelman (November 15, 2012). "ADAPTATION: Political support for a sea wall in New York Harbor begins to form". © 1996–2012 E&E Publishing, LLC. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ Julie Shapiro (January 11, 2012). "Downtown Baby Boom Sees 12 Percent Increase in Births". DNAinfo New York. Retrieved August 4, 2013.

- ^ C. J. Hughes (August 8, 2014). "The Financial District Gains Momentum". The New York Times. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ Winnie Hu (December 2, 2016). "Downside of Lower Manhattan's Boom: It's Just Too Crowded". The New York Times. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Jeff Gordinier (June 23, 2015). "Manhattan's Dining Center of Gravity Shifts Downtown". The New York Times. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ a b "2013 WFE Market Highlights" (PDF). World Federation of Exchanges. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sarah Waxman. "The History of New York's Chinatown". Mediabridge Infosystems, Inc. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ "Chinatown New York City Fact Sheet" (PDF). explorechinatown.com. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ a b NYC Basics, NYCvisit.com. Retrieved on December 2, 2007.

- ^ See, e.g., Hotels: Downtown below 23rd Street, Time Out New York; "Residents Angered By Bar Noise In Downtown Manhattan", NY 1 News, March 3, 2006. Both retrieved on December 3, 2007.

- ^ Downtown: Its Rise and Fall, 1880–1950 by Professor Robert M Fogelson. Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-300-09827-8. pg 3

- ^ "Lower Manhattan". New York City Economic Development Corporation. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ John Glover (November 23, 2014). "New York Boosts Lead on London as Leading Finance Center". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ^ "UBS may move US investment bank to NYC". e-Eighteen.com Ltd. June 10, 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ^

"Top 8 Cities by GDP: China vs. The U.S." Business Insider, Inc. July 31, 2011. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

For instance, Shanghai, the largest Chinese city with the highest economic production, and a fast-growing global financial hub, is far from matching or surpassing New York, the largest city in the U.S. and the economic and financial super center of the world.

"PAL sets introductory fares to New York". Philippine Airlines. Retrieved December 10, 2014. - ^ Richard Florida (3 March 2015). "Sorry, London: New York Is the World's Most Economically Powerful City". The Atlantic Monthly Group. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

Our new ranking puts the Big Apple firmly on top.

- ^ "The Global Financial Centres Index 17" (PDF). Long Finance. March 23, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ Ambereen Choudhury, Elisa Martinuzzi; Ben Moshinsky (November 26, 2012). "London Bankers Bracing for Leaner Bonuses Than New York". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Contact Us." Ambac Financial Group. Retrieved on December 11, 2009.

- ^ "Company Overview Archived 2009-02-18 at the Wayback Machine." AOL. Retrieved on May 7, 2009.

- ^ "Office Locations". Standard & Poor's. Retrieved on August 12, 2011. "Corporate 55 Water Street New York New York"

- ^ "LARGE EMPLOYER GROUP APPLICATION Archived 2013-05-12 at the Wayback Machine". EmblemHealth. Retrieved on August 12, 2011. "EmblemHealth, 55 Water Street, New York, New York 10041 HIP Insurance Company of New York, 55 Water Street, New York, NY 10041 Group Health Incorporated, 441 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY 10001"

- ^ "HIP CELEBRATES OPENING OF NEW HEADQUARTERS IN LOWER MANHATTAN RELOCATION OF 2,000 EMPLOYEES TO 55 WATER STREET REPRESENTS LARGEST CORPORATE RELOCATION TO LOWER MANHATTAN SINCE 9/11." HIP Health Plan. October 12, 2004. Retrieved on August 12, 2011.

- ^ "Univision sues over Nielsen's meters." Associated Press at the St. Petersburg Times. June 11, 2004. Retrieved on August 28, 2011. "New York is the corporate headquarters of Nielsen,[...]"

- ^ "Contact Us." Nielsen Company. Retrieved on August 28, 2011. "The Nielsen Company, 770 Broadway, New York, NY 10003-9595"

- ^ ""Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-07-26. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)." PR Newswire. Retrieved on July 20, 2014. - ^ [1]. Verizon Corporate Office Headquarters. Retrieved on July 30, 2014.

- ^ "office locations." Cantor Fitzgerald. March 4, 2000. Retrieved on October 4, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us." US Helicopter. Retrieved on September 25, 2009.

- ^ Ward's Business Directory of U.S. Private and Public Companies, 1995: Alphabetic listing, G-O Volume 2. Gale Research, 1995. "2073. Retrieved from Google Books on July 28, 2010. "Hi Tech Expressions Inc. 584 Broadway New York, NY 10012." ISBN 0-8103-8831-6, ISBN 978-0-8103-8831-4.

- ^ "Playin fair video-game manufacturers target an untapped market -- Girls". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. June 12, 1994. K-1. Retrieved on July 28, 2010. "Meanwhile, over at Hi Tech Expressions, a New York-based software company,"

- ^ "About the Port Authority." Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. June 22, 2000. Retrieved on January 22, 2010.

- ^ "New York Field Office." Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved on June 9, 2015. "26 Federal Plaza, 23rd Floor New York, NY 10278-0004"

- ^ "Biggest NY Subway Hub Opens; Expects 300,000 Daily". ABC News Internet Ventures. December 10, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ "World Trade Center Transportation Hub". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Retrieved December 10, 2014.