Tarzan

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Tarzan | |

|---|---|

| File:Tarzan (character).jpg Cover art for Lord of the Jungle #1 (December. 2011) by Alex Ross. | |

| First appearance | Tarzan of the Apes |

| Last appearance | Tarzan: the Lost Adventure |

| Created by | Edgar Rice Burroughs |

| Portrayed by | See film and other non-print media article section |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | John Clayton[1][2] |

| Species | Human |

| Gender | Male |

| Title | Viscount Greystoke[3] The American Ashwin [2] Earl of Greystoke[4] Chieftain of the Waziri |

| Occupation | Adventurer Hunter Trapper Fisherman |

| Spouse | Jane Porter (wife) |

| Children | Korak (son) |

| Relatives | William Cecil Clayton (cousin) Meriem (daughter-in-law) Jackie Clayton (grandson)[5] Dick & Doc (distant cousins) Bunduki (adopted son) Dawn (great-granddaughter) |

| Nationality | English |

| Abilities | Enhanced strength, speed, endurance, agility, durability, reflexes, and senses Able to communicate with animals Skilled hunter and fighter |

Tarzan (John Clayton, Viscount Greystoke) is a fictional character, an archetypal feral child raised in the African jungle by the Mangani great apes; he later experiences civilization only to largely reject it and return to the wild as a heroic adventurer. Created by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tarzan first appeared in the novel Tarzan of the Apes (magazine publication 1912, book publication 1914), and subsequently in 25 sequels, several authorized books by other authors, and innumerable works in other media, both authorized and unauthorized.

Character biography

Childhood years

Tarzan is the son of a British lord and lady who were marooned on the Atlantic coast of Africa by mutineers. When Tarzan was an infant, his mother died, and his father was killed by Kerchak, leader of the ape tribe by whom Tarzan was adopted. Soon after his parents' death, Tarzan became a feral child, and his tribe of apes are known as the Mangani, Great Apes of a species unknown to science. Kala is his ape mother. Burroughs added stories occurring during Tarzan's adolescence in his sixth Tarzan book, Jungle Tales of Tarzan. Tarzan is his ape name (meaning "White-Skin"); his English name is John Clayton, Viscount Greystoke (according to Burroughs in Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle; Earl of Greystoke in later, less canonical sources, notably the 1984 movie Greystoke). In fact, Burroughs's narrator in Tarzan of the Apes describes both Clayton and Greystoke as fictitious names – implying that, within the fictional world that Tarzan inhabits, he may have a different real name.

In his book Tarzan: The Biography, author Sean Egan argues that the name "Tarzan" is illogical, asserting that it is "a non-guttural word [that is] not the sort of sound that naturally emanates from the mouth of even a man-like simian." [6] He also says filmmakers down the decades have consistently failed to acknowledge the incongruity of Tarzan’s name, with a few exceptions, such as the 1998 movie Tarzan and the Lost City and the 2017 Netflix series Tarzan and Jane, which came up with a logical get-around by making the name one bequeathed by Africans, and Greystoke, which dispensed with the problem by jettisoning the name entirely.

Adult life

As an eighteen-year-old young adult, Tarzan meets a young American woman, Jane Porter. She, her father, and others of their party are marooned on the same coastal jungle area where Tarzan's biological parents were twenty years earlier. When Jane returns to the United States, Tarzan leaves the jungle in search of her, his one true love. In The Return of Tarzan, Tarzan and Jane marry. In later books he lives with her for a time in England. They have one son, Jack, who takes the ape name Korak ("the Killer"). Tarzan is contemptuous of what he sees as the hypocrisy of civilization, and he and Jane return to Africa, making their home on an extensive estate that becomes a base for Tarzan's later adventures.

As revealed in Tarzan's Quest, Tarzan, Jane, Tarzan's monkey friend Nkima, and their allies gained some of the Kavuru's pills that grant immortality to its consumer.

Characterization

Burroughs created an elegant version of the wild man figure largely unalloyed with character flaws or faults. Tarzan is described as being tall, athletic, handsome, and tanned, with grey eyes and long black hair. He wears almost no clothes, except for a loincloth. Emotionally, he is courageous, intelligent, loyal, and steadfast. He is presented as behaving ethically in most situations, except when seeking vengeance under the motivation of grief, as when his ape mother Kala is killed in Tarzan of the Apes, or when he believes Jane has been murdered in Tarzan the Untamed. He is deeply in love with his wife and totally devoted to her; in numerous situations where other women express their attraction to him, Tarzan politely but firmly declines their attentions. When presented with a situation where a weaker individual or party is being preyed upon by a stronger foe, Tarzan invariably takes the side of the weaker party. In dealing with other men, Tarzan is firm and forceful. With male friends, he is reserved but deeply loyal and generous. As a host, he is, likewise, generous and gracious. As a leader, he commands devoted loyalty.

In keeping with these noble characteristics, Tarzan's philosophy embraces an extreme form of "return to nature". Although he is able to pass within society as a civilized individual, he prefers to "strip off the thin veneer of civilization", as Burroughs often puts it.[7] His preferred dress is a knife and a loincloth of animal hide, his preferred abode is any convenient tree branch when he desires to sleep, and his favored food is raw meat, killed by himself; even better if he is able to bury it a week so that putrefaction has had a chance to tenderize it a bit.

Tarzan's primitivist philosophy was absorbed by countless fans, amongst whom was Jane Goodall, who describes the Tarzan series as having a major influence on her childhood. She states that she felt she would be a much better spouse for Tarzan than his fictional wife, Jane, and that when she first began to live among and study the chimpanzees she was fulfilling her childhood dream of living among the great apes just as Tarzan did.[8]

Rudyard Kipling's Mowgli has been cited as a major influence on Edgar Rice Burroughs' creation of Tarzan. Mowgli was also an influence for a number of other "wild boy" characters.

Skills and abilities

Tarzan's jungle upbringing gives him abilities far beyond those of ordinary humans. These include climbing, clinging, and leaping as well as any great ape, or better. He uses branches and hanging vines to swing at great speed, a skill acquired among the anthropoid apes.

His strength, speed, stamina, agility, reflexes, senses, flexibility, durability, endurance, and swimming are extraordinary in comparison to normal men. He has wrestled full grown bull apes and gorillas, lions, rhinos, crocodiles, pythons, sharks, tigers, man-size seahorses (once) and even dinosaurs (when he visited Pellucidar). Tarzan is a skilled tracker and uses his exceptional senses of hearing and smell to follow prey or avoid predators, and kills only for food, yet is a skilled thief when raiding African tribal villages or hunting parties that Tarzan has judged to be brutal and deserve no pity, taking their spears, shields, bows, knives, and most importantly, metal arrowheads. A keen sense of hearing allows him to eavesdrop on conversations between other people near him.

Extremely intelligent, Tarzan was literate in English before being able to speak the language when he first encounters other English-speaking people such as his love interest, Jane Porter. His literacy is self-taught after several years in his early teens by visiting the log cabin of his dead parents and looking at and correctly deducing the function of children's primer/picture books. The books were brought to Africa by his dead mother who intended to teach her son herself. He eventually reads every book in his dead father's portable book collection and is fully aware of geography, basic world history, and his family tree, yet is not able to speak English until after meeting human beings as he never heard what English is supposed to sound like when spoken aloud. He is "found" by a traveling Frenchman that teaches him the basics of human speech and returns him to England.

Tarzan can learn a new language in days, ultimately speaking many languages, including that of the great apes, French, Finnish, English, Dutch, German, Swahili, many Bantu dialects, Arabic, ancient Greek, ancient Latin, Mayan, the languages of the Ant Men and of Pellucidar.

Unlike depictions in black and white movies of the 1930s after learning to speak a language in the novels, Tarzan/John Clayton is very articulate, reserved (he prefers to listen and carefully observe before speaking) and does not speak in broken English as the classic movies depict him.

He can communicate with many species of jungle animals, and has been shown to be a skilled impressionist, able to mimic the sound of a gunshot perfectly.

The Kavuru's pills later granted Tarzan immortality.

Literature

Tarzan has been called one of the best-known literary characters in the world.[9] In addition to more than two dozen books by Burroughs and a handful more by authors with the blessing of Burroughs' estate, the character has appeared in films, radio, television, comic strips, and comic books. Numerous parodies and pirated works have also appeared.

Burroughs considered other names for the character, including "Zantar" and "Tublat Zan," before he settled on "Tarzan."[10]

Even though the copyright on Tarzan of the Apes has expired in the United States of America and other countries, the name Tarzan is claimed as a trademark of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.

It's also worth noting that Burroughs use of dates and time passing is constantly inconsistent in his novels, in fact there are downright contradictions in the series. In the first book Tarzan Of The Apes it's implied that Tarzan was born early in 1888 and the arrival of Jane is said to have occurred in 1909 which would make him 20 years old. In Tarzan Of The Apes, chapter 9, Burroughs states:

- Thus, at eighteen, we find him, an English lordling, who could speak no English, and yet who could read and write his native language. Never had he seen a human being other than himself, for the little area traversed by his tribe was watered by no great river to bring down the savage natives of the interior.

Two paragraphs later Mbonga's warriors enter. Yet in The Return Of Tarzan, chapter 5, when the ape man almost killed the Count de Coude Tarzan states:

- Until I was fifteen I had never seen a human being. I was twenty before I saw a white man.

However the book makes multiple references to the fact that John Clayton II and his wife Alice were only missing for 20 years, which means that Tarzan would only be 18–19 years of age, numerous authorised movies and novels have all agreed with the notion of Tarzan being 18 years old during the events of the first novel. A later novel Tarzan the Untamed faces a similar problem with the novel being set in the year 1914, despite the fact that Tarzan and Jane's son, Jack 'Korak' Clayton is supposed to be 18 years old. It's believed among fans that Burroughs did this deliberately to give an illusion that Tarzan had once been an actual person and Burroughs was trying to conceal his real identity, in the first novel it is mentioned:

- I had this story from one who had no business to tell it to me, or to any other. I may credit the seductive influence of an old vintage upon the narrator for the beginning of it, and my own skeptical incredulity during the days that followed for the balance of the strange tale. When my convivial host discovered that he had told me so much, and that I was prone to doubtfulness, his foolish pride assumed the task the old vintage had commenced, and so he unearthed written evidence in the form of musty manuscript, and dry official records of the British Colonial Office to support many of the salient features of his remarkable narrative. I do not say the story is true, for I did not witness the happenings which it portrays, but the fact that in the telling of it to you I have taken fictitious names for the principal characters quite sufficiently evidences the sincerity of my own belief that it MAY be true. The yellow, mildewed pages of the diary of a man long dead, and the records of the Colonial Office dovetail perfectly with the narrative of my convivial host, and so I give you the story as I painstakingly pieced it out from these several various agencies. If you do not find it credible you will at least be as one with me in acknowledging that it is unique, remarkable, and interesting.

Burroughs immediately mentions after this that John Clayton is itself a fictitious name, invented by 'Tarzan' to mask his real identity.

Critical reception

While Tarzan of the Apes met with some critical success, subsequent books in the series received a cooler reception and have been criticized for being derivative and formulaic. The characters are often said to be two-dimensional, the dialogue wooden, and the storytelling devices (such as excessive reliance on coincidence) strain credulity. According to author Rudyard Kipling (who himself wrote stories of a feral child, The Jungle Book's Mowgli), Burroughs wrote Tarzan of the Apes just so that he could "find out how bad a book he could write and get away with it."[11]

While Burroughs is not a polished novelist, he is a vivid storyteller, and many of his novels are still in print.[12] In 1963, author Gore Vidal wrote a piece on the Tarzan series that, while pointing out several of the deficiencies that the Tarzan books have as works of literature, praises Edgar Rice Burroughs for creating a compelling "daydream figure".[13] Critical reception grew more positive with the 1981 study by Erling B. Holtsmark, Tarzan and Tradition: Classical Myth in Popular Literature.[14] Holtsmark added a volume on Burroughs for Twayne's United States Author Series in 1986.[15] In 2010, Stan Galloway provided a sustained study of the adolescent period of the fictional Tarzan's life in The Teenage Tarzan.[16]

Despite critical panning, the Tarzan stories have remained popular. Burroughs's melodramatic situations and the elaborate details he works into his fictional world, such as his construction of a partial language for his great apes, appeal to a worldwide fan base.[17]

The Tarzan books and movies employ extensive stereotyping to a degree common in the times in which they were written. This has led to criticism in later years, with changing social views and customs, including charges of racism since the early 1970s.[18] The early books give a pervasively negative and stereotypical portrayal of native Africans, including Arabs. In The Return of Tarzan, Arabs are "surly looking" and call Christians "dogs", while blacks are "lithe, ebon warriors, gesticulating and jabbering". One could make an equal argument that when it came to blacks that Burroughs was simply depicting unwholesome characters as unwholesome and the good ones in a better light as in Chapter 6 of Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar where Burroughs writes of Mugambi, "...nor could a braver or more loyal guardian have been found in any clime or upon any soil."[19] Other groups are stereotyped as well. A Swede has "a long yellow moustache, an unwholesome complexion, and filthy nails", and Russians cheat at cards. The aristocracy (except the House of Greystoke) and royalty are invariably effete.[20] In later books, Africans are portrayed somewhat more realistically as people. For example, in Tarzan's Quest, while the depiction of Africans remains relatively primitive, they are portrayed more individualistically, with a greater variety of character traits (positive and negative), while the main villains are white people. Burroughs never loses his distaste for European royalty, though.[21]

Burroughs' opinions, manifested through the narrative voice in the stories, reflect common attitudes in his time, which in a 21st-century context would be considered racist and sexist. However Thomas F. Bertonneau writes about Burroughs' "conception of the feminine that elevates the woman to the same level as the man and that—in such characters as Dian of the Pellucidar novels or Dejah Thoris of the Barsoom novels—figures forth a female type who corresponds neither to desperate housewife, full-lipped prom-date, middle-level careerist office-manager, nor frowning ideological feminist-professor, but who exceeds all these by bounds in her realized humanity and in so doing suggests their insipidity."[22] The author is not especially mean-spirited in his attitudes. His heroes do not engage in violence against women or in racially motivated violence. In Tarzan of the Apes, details of a background of suffering experienced at the hands of whites by Mbonga's "once great" people are repeatedly told with evident sympathy, and in explanation or even justification of their current animosity toward whites.

Although the character of Tarzan does not directly engage in violence against women, feminist scholars have critiqued the presence of other sympathetic male characters who do with Tarzan's approval.[23] In Tarzan and the Ant Men, the men of a fictional tribe of creatures called the Alali gain social dominance of their society by beating Alali women into submission with weapons that Tarzan willingly provides them.[23] Following the battle, Burroughs states: "To entertain Tarzan and to show him what great strides civilization had taken—the son of The First Woman seized a female by the hair and dragging her to him struck her heavily about the head and face with his clenched fist, and the woman fell upon her knees and fondled his legs, looking wistfully into his face, her own glowing with love and admiration. (178)"[23] While Burroughs depicts some female characters with humanistic equalizing elements, Torgovnick argues that violent scenes against women in the context of male political and social domination are condoned in his writing, reinforcing a notion of gendered hierarchy where patriarchy is portrayed as the natural pinnacle of society.[23]

In regards to race, a superior–inferior relationship with valuation is also accordingly implied, as it is unmistakable in virtually all interactions between whites and blacks in the Tarzan stories, and similar relationships and valuations can be seen in most other interactions between differing people, although one could argue that such interactions are the bedrock of the dramatic narrative and without such valuations there is no story. According to James Loewen's Sundown Towns, this may be a vestige of Burroughs' having been from Oak Park, Illinois, a former Sundown town (a town that forbids non-whites from living within it).

Gail Bederman takes a different view in her Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917. There she describes how various people of the time either challenged or upheld the idea that "civilization" is predicated on white masculinity. She closes with a chapter on 1912's Tarzan of the Apes because the story's protagonist is, according to her, the ultimate male by the standards of 1912 white America. Bederman does note that Tarzan, "an instinctivily chivalrous Anglo-Saxon", does not engage in sexual violence, renouncing his "masculine impulse to rape." However, she also notes that not only does Tarzan kill black man Kulonga in revenge for killing his ape mother (a stand-in for his biological white mother) by hanging him, "lyncher Tarzan" actually enjoys killing black people, the cannibalistic Mbongans, for example. Bederman, in fact, reminds readers that when Tarzan first introduces himself to Jane, he does so as "Tarzan, the killer of beasts and many black men." The novel climaxes with Tarzan saving Jane—who in the original novel is not British, but a white woman from Baltimore, Maryland—from a black ape rapist. When he leaves the jungle and sees "civilized" Africans farming, his first instinct is to kill them just for being black. "Like the lynch victims reported in the Northern press, Tarzan's victims—cowards, cannibals, and despoilers of white womanhood—lack all manhood. Tarzan's lynchings thus prove him the superior man."

Despite embodying all the tropes of white supremacy espoused or rejected by the people she had reviewed (Theodore Roosevelt, G. Stanley Hall, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Ida B. Wells), Bederman states that, in all probability, Burroughs was not trying to make any kind of statement or echo any of them. "He probably never heard of any of them." Instead, Bederman writes that Burroughs proves her point because in telling racist and sexist stories whose protagonist boasted of killing blacks, he was not being unusual at all, but was instead just being a typical 1912 white American.

Tarzan is a white European male who grows up with apes. According to "Taking Tarzan Seriously" by Marianna Torgovnick, Tarzan is confused with the social hierarchy that he is a part of. Unlike everyone else in his society, Tarzan is the only one who is not clearly part of any social group. All the other members of his world are not able to climb or decline socially because they are already part of a social hierarchy which is stagnant. Turgovnick writes that since Tarzan was raised as an ape, he thinks and acts like an ape. However, instinctively he is human and he resorts to being human when he is pushed to. The reason of his confusion is that he does not understand what the typical white male is supposed to act like. His instincts eventually kick in when he is in the midst of this confusion, and he ends up dominating the jungle. In Tarzan, the jungle is a microcosm for the world in general in 1912 to the early 1930s. His climbing of the social hierarchy proves that the European white male is the most dominant of all races/sexes, no matter what the circumstance. Furthermore, Turgovnick writes that when Tarzan first meets Jane, she is slightly repulsed but also fascinated by his animal-like actions. As the story progresses, Tarzan surrenders his knife to Jane in an oddly chivalrous gesture, which makes Jane fall for Tarzan despite his odd circumstances. Turgovnick believes that this displays an instinctual, civilized chivalry that Burrough believes is common in white men.[24][25]

Unauthorized works

After Burroughs' death a number of writers produced new Tarzan stories. In some instances, the estate managed to prevent publication of such works. The most notable example in the United States was a series of five novels by the pseudonymous "Barton Werper" that appeared 1964–65 by Gold Star Books (part of Charlton Comics). As a result of legal action by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc., they were taken off the market.[26] Similar series appeared in other countries, notably Argentina, Israel, and some Arab countries.

Modern fiction

In 1972, science fiction author Philip José Farmer wrote Tarzan Alive, a biography of Tarzan utilizing the frame device that he was a real person. In Farmer's fictional universe, Tarzan, along with Doc Savage and Sherlock Holmes, are the cornerstones of the Wold Newton family. Farmer wrote two novels, Hadon of Ancient Opar and Flight to Opar, set in the distant past and giving the antecedents of the lost city of Opar, which plays an important role in the Tarzan books. In addition, Farmer's A Feast Unknown, and its two sequels Lord of the Trees and The Mad Goblin, are pastiches of the Tarzan and Doc Savage stories, with the premise that they tell the story of the real characters the fictional characters are based upon. A Feast Unknown is somewhat infamous among Tarzan and Doc Savage fans for its graphic violence and sexual content.[citation needed]

Tarzan in film and other non-print media

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

Film

The first Tarzan movies were silent pictures adapted from the original Tarzan novels, which appeared within a few years of the character's creation. The first actor to portray the adult Tarzan was Elmo Lincoln in 1918's film Tarzan of the Apes. With the advent of talking pictures, a popular Tarzan movie franchise was developed, which lasted from the 1930s through the 1960s. Starting with Tarzan the Ape Man in 1932 through twelve films until 1948, the franchise was anchored by former Olympic swimmer Johnny Weissmuller in the title role. Weissmuller and his immediate successors were enjoined to portray the ape-man as a noble savage speaking broken English, in marked contrast to the cultured aristocrat of Burroughs's novels.

With the exception of the Burroughs co-produced The New Adventures of Tarzan, this "me Tarzan, you Jane" characterization of Tarzan persisted until the late 1950s, when producer Sy Weintraub, having bought the film rights from producer Sol Lesser, produced Tarzan's Greatest Adventure followed by eight other films and a television series. The Weintraub productions portray a Tarzan that is closer to Edgar Rice Burroughs' original concept in the novels: a jungle lord who speaks grammatical English and is well educated and familiar with civilization. Most Tarzan films made before the mid-fifties were black-and-white films shot on studio sets, with stock jungle footage edited in. The Weintraub productions from 1959 on were shot in foreign locations and were in color.

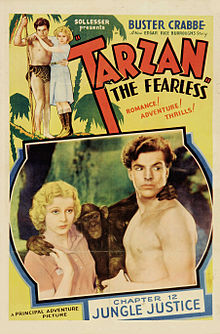

There were also several serials and features that competed with the main franchise, including Tarzan the Fearless (1933) starring Buster Crabbe and The New Adventures of Tarzan (1935) starring Herman Brix. The latter serial was unique for its period in that it was partially filmed on location (Guatemala) and portrayed Tarzan as educated. It was the only Tarzan film project for which Edgar Rice Burroughs was personally involved in the production.

Tarzan films from the 1930s on often featured Tarzan's chimpanzee companion Cheeta, his consort Jane (not usually given a last name), and an adopted son, usually known only as "Boy." The Weintraub productions from 1959 on dropped the character of Jane and portrayed Tarzan as a lone adventurer. Later Tarzan films have been occasional and somewhat idiosyncratic.

Recently, Tony Goldwyn portrayed Tarzan in Disney’s animated film of the same name (1999). This version marked a new beginning for the ape man, taking its inspiration equally from Burroughs and the 1984 live-action film Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes.

Since Greystoke, two additional live-action Tarzan movies have been released, 1998's Tarzan and the Lost City and 2016's The Legend of Tarzan, both period pieces that drew inspiration from Edgar Rice Burroughs' writings.

Radio

Tarzan was the hero of two popular radio programs in the United States. The first aired from 1932–1936 with James Pierce in the role of Tarzan. The second ran from 1951–1953 with Lamont Johnson in the title role.[27]

Television

Television later emerged as a primary vehicle bringing the character to the public. From the mid-1950s, all the extant sound Tarzan films became staples of Saturday morning television aimed at young and teenaged viewers. In 1958, movie Tarzan Gordon Scott filmed three episodes for a prospective television series. The program did not sell, but a different live action Tarzan series produced by Sy Weintraub and starring Ron Ely ran on NBC from 1966 to 1968. This depiction of Tarzan is a well-educated bachelor who grew tired of urban civilization and is in his native African jungle once again.

An animated series from Filmation, Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle, aired from 1976 to 1977, followed by the anthology programs Batman/Tarzan Adventure Hour (1977–1978), Tarzan and the Super 7 (1978–1980), The Tarzan/Lone Ranger Adventure Hour (1980–1981), and The Tarzan/Lone Ranger/Zorro Adventure Hour (1981–1982). In those cartoons, Tarzan was voiced by Robert Ridgely.

Joe Lara starred in the title role in Tarzan in Manhattan (1989), an offbeat TV movie, and later returned in a completely different interpretation in Tarzan: The Epic Adventures (1996), a new live-action series.

In between the two productions with Lara, Tarzán, a half-hour syndicated series ran from 1991 through 1994. In this version of the show, Tarzan was portrayed as a blond environmentalist, with Jane turned into a French ecologist.

Disney’s animated series The Legend of Tarzan (2001–2003) was a spin-off from its animated film.

The latest television series was the short-lived live-action Tarzan (2003), which starred male model Travis Fimmel and updated the setting to contemporary New York City, with Jane as a police detective, played by Sarah Wayne Callies. The series was cancelled after only eight episodes.

Saturday Night Live featured recurring sketches with the speech-impaired trio of "Tonto, Tarzan, and Frankenstein's Monster". In those sketches, Tarzan is portrayed by Kevin Nealon.

Stage

A 1921 Broadway production of Tarzan of The Apes starred Ronald Adair as Tarzan and Ethel Dwyer as Jane Porter. In 1976, Richard O'Brien wrote a musical entitled T. Zee, loosely based on Tarzan but restyled in a rock idiom. Tarzan, a musical stage adaptation of the 1999 animated feature, opened at the Richard Rodgers Theatre on Broadway on May 10, 2006. The show, a Disney Theatrical production, was directed and designed by Bob Crowley. The same version of Tarzan that was played at the Richard Rodgers Theatre is being played throughout Europe and has been a huge success in the Netherlands. The Broadway show closed on July 8, 2007. Tarzan also appeared in the Tarzan Rocks! show at the Theatre in the Wild at Walt Disney World Resort's Disney's Animal Kingdom. The show closed in 2006.

Video and computer games

In the mid-1980s there was an arcade video game called Jungle King that featured a Tarzanesque character in a loin cloth. A game under the title Tarzan Goes Ape, with little connection to the franchise, was released in the 1980s for the Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum. A Tarzan computer game by Michael Archer was produced by Martech. Disney's Tarzan had seen video games released for the PlayStation, Nintendo 64 and Game Boy Color. Followed by Disney's Tarzan Untamed for the PS2 and Gamecube. Tarzan also appeared in the PS2 game Kingdom Hearts, although this Tarzan was shown in the Disney context, not the original conceptional idea of Tarzan by Burroughs. In the first Rayman, a Tarzanesque version of Rayman named Tarayzan appears in the Dream Forest.

Action figures

Throughout the 1970s Mego Corporation licensed the Tarzan character and produced 8" action figures which they included in their "World's Greatest Super Heroes" line of characters. In 1975 they also produced a 3" "Bendy" figure made of poseable, malleable plastic.

Ephemera

Several Tarzan-themed products have been manufactured, including View-Master reels and packets, numerous Tarzan coloring books, children's books, follow-the-dots, and activity books.

Tarzan in comics

Tarzan of the Apes was adapted in newspaper strip form, in early 1929, with illustrations by Hal Foster. A full page Sunday strip began March 15, 1931 by Rex Maxon. Over the years, many artists have drawn the Tarzan comic strip, notably Burne Hogarth, Russ Manning, and Mike Grell. The daily strip began to reprint old dailies after the last Russ Manning daily (#10,308, which ran on 29 July 1972). The Sunday strip also turned to reprints circa 2000. Both strips continue as reprints today in a few newspapers and in Comics Revue magazine. NBM Publishing did a high quality reprint series of the Foster and Hogarth work on Tarzan in a series of hardback and paperback reprints in the 1990s.

Tarzan has appeared in many comic books from numerous publishers over the years. The character's earliest comic book appearances were in comic strip reprints published in several titles, such as Sparkler, Tip Top Comics and Single Series. Western Publishing published Tarzan in Dell Comics's Four Color Comics #134 & 161 in 1947, before giving him his own series, Tarzan, published through Dell Comics and later Gold Key Comics from January–February 1948 to February 1972). DC took over the series in 1972, publishing Tarzan #207–258 from April 1972 to February 1977, including work by Joe Kubert. In 1977 the series moved to Marvel Comics, which restarted the numbering rather than assuming that used by the previous publishers. Marvel issued Tarzan #1–29 (as well as three Annuals), from June 1977 to October 1979, mainly by John Buscema. Following the conclusion of the Marvel series the character had no regular comic book publisher for a number of years. During this period Blackthorne Comics published Tarzan in 1986, and Malibu Comics published Tarzan comics in 1992. Dark Horse Comics has published various Tarzan series from 1996 to the present, including reprints of works from previous publishers like Gold Key and DC, and joint projects with other publishers featuring crossovers with other characters.

There have also been a number of different comic book projects from other publishers over the years, in addition to various minor appearances of Tarzan in other comic books. The Japanese manga series Jungle no Ouja Ta-chan (Jungle King Tar-chan) by Tokuhiro Masaya was based loosely on Tarzan. Also, manga "god" Osamu Tezuka created a Tarzan manga in 1948 entitled Tarzan no Himitsu Kichi (Tarzan's Secret Base).

Works inspired by Tarzan

Jerry Siegel named Tarzan and another Burroughs character, John Carter, as early inspiration for his creation of Superman.[28]

Tarzan's popularity inspired numerous imitators in pulp magazines. A number of these, like Kwa and Ka-Zar were direct or loosely veiled copies; others, like Polaris of the Snows, were similar characters in different settings, or with different gimmicks. Of these characters the most popular was Ki-Gor, the subject of fifty-nine novels that appeared between winter 1939 to spring 1954 in the magazine Jungle Stories.[29]

Species named after Tarzan

Tarzan is commemorated in the scientific name of a species of chameleon, Calumma tarzan, which is endemic to Madagascar.[30]

In popular culture

Tarzan is often used as a nickname to indicate a similarity between a person's characteristics and that of the fictional character. Individuals with an exceptional 'ape-like' ability to climb, cling and leap beyond that of ordinary humans may often receive the nickname 'Tarzan'.[31] An example is retired American baseball player Joe Wallis.[32]

Comedian Carol Burnett was often prompted by her audiences to perform her trademark Tarzan yell. She explained that it originated in her youth when she and a friend watched a Tarzan movie.[33]

Tarzan and Pellucidar main series chronology

- Tarzan of the Apes Chapters 1 to 11 (1912) (Project Gutenberg Entry:Ebook) (LibriVox.org Audiobook)

- Jungle Tales of Tarzan (1919) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- "Tarzan's First Love" (1916)

- "The Capture of Tarzan" (1916)

- "The Fight for the Balu" (1916)

- "The God of Tarzan" (1916)

- "Tarzan and the Black Boy" (1917)

- "The Witch-Doctor Seeks Vengeance" (1917)

- "The End of Bukawai" (1917)

- "The Lion" (1917)

- "The Nightmare" (1917)

- "The Battle for Teeka" (1917)

- "A Jungle Joke" (1917)

- "Tarzan Rescues the Moon" (1917)

- Tarzan of the Apes Chapters 11 to 28 (1912) (Project Gutenberg Entry:Ebook) (LibriVox.org Audiobook)

- The Return of Tarzan (1913) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- The Beasts of Tarzan (1914) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- At the Earth's Core (1914)

- The Son of Tarzan Chapters 1 to 12 (1915) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- Pellucidar (1915)

- Tarzan and the Forbidden City (1938) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar (1916) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- The Son of Tarzan Chapters 13 to 27 (1915) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- "The Eternal Lover" (The Eternal Lover Part 1) All-Story Weekly, March 7, 1914

- "The Mad King" (The Mad King Part 1) All-Story Weekly March 21, 1914

- "Sweetheart Primeval" (The Eternal Lover Part 2) All-Story Weekly, Jan.–Feb. 1915

- "Barney Custer of Beatrice" (The Mad King Part 2) All-Story Weekly, August 1915

- Tarzan the Untamed (1920) (Ebook)

- "Tarzan and the Huns" (1919)

- "Tarzan and the Valley of Luna" (1920)

- Tarzan the Terrible (1921) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- Tarzan and the Golden Lion (1922, 1923) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the Ant Men (1924) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the Tarzan Twins (1963, for younger readers)

- Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle (1927, 1928) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the Lost Empire (1928) (Ebook)

- Tanar of Pellucidar (1929)

- Tarzan at the Earth's Core (1929) (Ebook)

- Tarzan the Invincible (1930, 1931) (Ebook)

- Tarzan Triumphant (1931) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the City of Gold (1932) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the Lion Man (1933, 1934) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the Leopard Men (1935) (Ebook)

- Tarzan's Quest (1935, 1936) (Ebook)

- Tarzan the Magnificent (1939) (Ebook)

- "Tarzan and the Magic Men" (1936)

- Back to the Stone Age (1937)

- Tarzan and the Elephant Men" (1937–1938)

- Tarzan and the Champion" (1940)

- Tarzan and the Jungle Murders" (1940)

- Tarzan and the Madman (1964)

- Tarzan and the Castaways (1941) (Ebook)

- Land of Terror (1944)

- Tarzan and the Foreign Legion (1947) (Ebook)

- Savage Pellucidar (1963)

- "The Return to Pellucidar"

- "Men of the Bronze Age"

- "Tiger Girl"

- "Savage Pellucidar"

- Tarzan: the Lost Adventure (unfinished, completed by Joe R. Lansdale) (1995)

Bibliography

By Edgar Rice Burroughs

- Main Series

- Tarzan of the Apes (1912) (Project Gutenberg Entry:Ebook) (LibriVox.org Audiobook)

- The Return of Tarzan (1913) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- The Beasts of Tarzan (1914) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- The Son of Tarzan (1915) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar (1916) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- Jungle Tales of Tarzan (1919) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- "Tarzan's First Love" (1916)

- "The Capture of Tarzan" (1916)

- "The Fight for the Balu" (1916)

- "The God of Tarzan" (1916)

- "Tarzan and the Black Boy" (1917)

- "The Witch-Doctor Seeks Vengeance" (1917)

- "The End of Bukawai" (1917)

- "The Lion" (1917)

- "The Nightmare" (1917)

- "The Battle for Teeka" (1917)

- "A Jungle Joke" (1917)

- "Tarzan Rescues the Moon" (1917)

- Tarzan the Untamed (1920) (Ebook)

- "Tarzan and the Huns" (1919)

- "Tarzan and the Valley of Luna" (1920)

- Tarzan the Terrible (1921) (Ebook) (Audiobook)

- Tarzan and the Golden Lion (1922, 1923) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the Ant Men (1924) (Ebook)

- Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle (1927, 1928) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the Lost Empire (1928) (Ebook)

- Tarzan at the Earth's Core (1929) (Ebook)

- Tarzan the Invincible (1930, 1931) (Ebook)

- Tarzan Triumphant (1931) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the City of Gold (1932) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the Lion Man (1933, 1934) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the Leopard Men (1935) (Ebook)

- Tarzan's Quest (1935, 1936) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the Forbidden City (1938) (Ebook)

- Tarzan the Magnificent (1939) (Ebook)

- "Tarzan and the Magic Men" (1936)

- "Tarzan and the Elephant Men" (1937–1938)

- Tarzan and the Foreign Legion (1947) (Ebook)

- Tarzan and the Madman (1964)

- Tarzan and the Castaways (1965)

- "Tarzan and the Castaways" (1941) (Ebook)

- "Tarzan and the Champion" (1940)

- "Tarzan and the Jungle Murders" (1940)

- Tarzan and the Tarzan Twins (1963, for younger readers)

- Tarzan: the Lost Adventure (with Joe R. Lansdale) (1995)

By other authors

- Barton Werper – these novels were never authorized by the Burroughs estate, were taken off the market and remaining copies destroyed.

- Tarzan and the Silver Globe (1964)

- Tarzan and the Cave City (1964)

- Tarzan and the Snake People (1964)

- Tarzan and the Abominable Snowmen (1965)

- Tarzan and the Winged Invaders (1965)

- Fritz Leiber – the first novel authorized by the Burroughs estate, and numbered as the 25th book in the Tarzan series.

- Philip José Farmer

- Tarzan Alive (1972) a fictional biography of Tarzan (here Lord Greystoke), which is one of the two foundational books (along with Doc Savage: His Apocalyptic Life) of the Wold Newton family.

- The Adventure of the Peerless Peer (1974) Sherlock Holmes goes to Africa and meets Tarzan.

- The Dark Heart of Time (1999) this novel was specifically authorized by the Burroughs estate, and references Tarzan by name rather than just by inference. The story is set between Tarzan the Untamed and Tarzan the Terrible.

- Farmer also wrote a novel based on his own fascination with Tarzan, entitled Lord Tyger, and translated the novel Tarzan of the Apes into Esperanto.

- R. A. Salvatore

- Tarzan: The Epic Adventures (1996) an authorized novel based on the pilot episode of the series of the same name.

- Nigel Cox

- Tarzan Presley (2004) This novel combines aspects of Tarzan and Elvis Presley into a single character named Tarzan Presley, within New Zealand and American settings. Upon its release, it was subject to legal action in the United States, and has not been reprinted since its initial publication.

- New Tarzan

Publisher Faber and Faber with the backing of the Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. have updated the series using author Andy Briggs. In 2011 he published the first of the books Tarzan: The Greystoke Legacy. In 2012 he published the second book Tarzan: The Jungle Warrior In 2013, he has published the third book Tarzan: The Savage Lands.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ In Burroughs, Edgar Rice (1914). "Chapter XXV". Tarzan of the Apes.

our little boy... the second John Clayton

(Check the next reference) - ^ a b Farmer, Philip José (1972). "Chapter One". Tarzan Alive: A Definitive Biography of Lord Greystoke. p. 8.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Burroughs, Edgar Rice (1928). Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle.

- ^ Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes. Warner Bros. 1984.

- ^ Burroughs, Edgar Rice (1924). "Chapter Two". Tarzan and the Ant Men.

- ^ Egan, Sean, Tarzan: The Biography, Askill Publishing, London, 2017, p. 27

- ^ The Return of Tarzan, chapter 2, being the earliest instance.

- ^ See The Jane Goodall Institute's Biography of Jane Goodall [1].

- ^ John Clute and Peter Nicholls, The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, St. Martin's Press, 1993, ISBN 0-312-09618-6, p. 178, "Tarzan is a remarkable creation, and possibly the best-known fictional character of the century."

- ^ "Edgar Rice Burroughs Inc". Tarzan.org. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ Gail Bederman,Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917, University of Chicago Press, 1995, pages 219.

- ^ John Clute and Peter Nicholls, The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, St. Martin's Press, 1993, ISBN 0-312-09618-6, p. 178, "It has often been said that ERB's works have small literary or intellectual merit. Nevertheless,...because ERB had a genius for the literalization of the dream, they have endured."

- ^ "Tarzan Revisited" by Gore Vidal.

- ^ Erling B. Holtsmark, Tarzan and Tradition: Classical Myth in Popular Literature, Greenwood Press, 1981.

- ^ Erling B. Holtsmark, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Twayne's United States Author Series, Twayne Publishers, 1986.

- ^ Stan Galloway, The Teenage Tarzan: A Literary Analysis of Edgar Rice Burroughs' Jungle Tales of Tarzan, McFarland, 2010.

- ^ "Bozarth, David Bruce. "Ape-English Dictionary"". Erblist.com. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ Rothschild, Bertram (1999). "Tarzan – Review". Humanist.

- ^ Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar, A.C. McClurg, 1918

- ^ Edgar Rice Burroughs, The Return of Tarzan, Grosset & Dunlap, 1915 ASIN B000WRZ2NG.

- ^ Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tarzan's Quest, Grosset & Dunlop, 1936, ASIN B000O3K9EU.

- ^ [2] Edgar Rice Burroughs and Masculine Narrative by Thomas F. Bertonneau

- ^ a b c d Torgovnick, Mariana (1990). Gone Primitive. University of Chicago press. pp. 42–72. ISBN 978-0226808321.

- ^ Gail Bederman,Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917, University of Chicago Press, 1995, pages 224–232.

- ^ Turgovnick, Mariana “Taking Tarzan Seriously” from Gone Primitive, University of Chicago Press 1990 [Ch 2 pp.42–72]

- ^ Werper, Barton

- ^ Robert R. Barrett, Tarzan on Radio, Radio Spirits, 1999.

- ^ http://www.omgfacts.com/lists/9079/Tarzan-was-an-early-inspiration-for-the-character-of-Superman

- ^ Hutchison, Don (2007). The Great Pulp Heroes. Book Republic Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-58042-184-3.

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Tarzan", pp. 260–261).

- ^ [3][dead link] [dead link]

- ^ Markusen, Bruce (2009-08-14). "Cooperstown Confidential: Tarzan Joe Wallis". Hardballtimes.com. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ King, Larry (2013-04-17). "Larry King interviews Carol Burnett". Hulu.com. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ^ "Letter by E. R. Burroughs". Exlibris-art.com. 1922-02-04. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

Further reading

- Annette Wannamaker and Michelle Ann Abate, eds. Global Perspectives on Tarzan: From King of the Jungle to International Icon (Routledge; 2012) 216 pages; studies by scholars from the United States, Australia, Canada, Israel, the Netherlands, Germany, and France.

External links

- Tarzan

- Tarzan characters

- Fantasy books by series

- Fantasy film characters

- Fictional characters introduced in 1912

- Comics characters introduced in 1929

- Fictional characters with immortality

- Fictional Central African people

- Fictional English people

- Fictional feral children

- Fictional orphans

- Fictional dukes and duchesses

- Fictional viscounts and viscountesses

- Fictional earls

- Fictional tribal chiefs

- Film serial characters

- Jungle men

- Jungle superheroes

- Kingdom Hearts characters

- Series of books

- Male characters in literature

- Male characters in comics