Aspasia: Difference between revisions

WP:BOLDly rewriting per talkpage discussion - restructuring, cutting some stuff which is less directly relevant, citing thoroughly to modern reliable sources, trimming less relevant/verifiable categories |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{short description|Milesian woman, involved with Athenian statesman Pericles}} |

{{short description|Milesian woman, involved with Athenian statesman Pericles}} |

||

[[ |

[[File:Aspasie Pio-Clementino Inv272.jpg|thumb|right|Marble portrait [[herm]] identified by an inscription as Aspasia, possibly copied from her grave.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=17}}]] |

||

'''Aspasia''' ({{IPAc-en|æ|ˈ|s|p|eɪ|ʒ|(|i|)|ə|,_|-|z|i|ə|,_|-|ʃ|ə}};<ref>''Collins English Dictionary'', "[https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/aspasia Aspasia]"</ref> {{lang-grc-gre|[[wikt:Ἀσπασία|Ἀσπασία]]}} {{IPA-el|aspasíaː|lang}}; {{circa|470}}{{snd}}after 428 BC{{efn|Aspasia's date of birth and death are uncertain. Her birthdate is inferred to be c. 470 BC based on the birthdates of her children;{{sfn|Bicknell|1982}} nothing is known of her life after her supposed relationship with [[Lysicles (5th century BC)|Lysicles]] (429–428 BC),{{sfn|Henry|1995}} although the structure of [[Aeschines of Sphettus|Aeschines]]' dialogue ''Aspasia'' implies that she died before the execution of [[Socrates]] in 399.{{sfn|Taylor|1955|p=41}}}}) was a [[metic]] woman in [[Classical Athens]]. Born in [[Miletus]], she moved to Athens and began a relationship with the statesman [[Pericles]], with whom she had a son, [[Pericles the Younger]]. Though she is one of the best-attested women from the Greco-Roman world, almost nothing is certain about her life. |

|||

Aspasia was portrayed in [[Old Comedy]] as a prostitute and madam, and in ancient philosophy as a teacher and rhetorician. She has continued to be a subject of both visual and literary artists until the present. From the twentieth century, she has been portrayed as both a sexualised and sexually liberated woman, and as a feminist role model fighting for women's rights in ancient Athens. |

|||

'''Aspasia of Miletus''' ({{IPAc-en|æ|ˈ|s|p|eɪ|ʒ|(|i|)|ə|,_|-|z|i|ə|,_|-|ʃ|ə}};<ref>''Collins English Dictionary'', "[https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/aspasia Aspasia]"</ref> {{lang-grc-gre|[[wikt:Ἀσπασία|Ἀσπασία]]}} {{IPA-el|aspasíaː|lang}}; c. 470<ref name="Nails58-59">D. Nails, ''The People of Plato'', Hackett Publishing pp. 58–59</ref><ref>[[Patricia O'Grady|P. O'Grady]], [http://home.vicnet.net.au/~hwaa/artemis4.html Aspasia of Miletus] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061201015330/http://home.vicnet.net.au/~hwaa/artemis4.html |date=December 1, 2006 }}</ref>–c. 400 BC)<ref name="Nails58-59" /><ref name="Taylor41">A.E. Taylor, ''Plato: The Man and his Work'', 41</ref> was an influential [[metic]] woman in [[Classical Athens|Classical-era Athens]] who, according to [[Plutarch]], attracted the most prominent writers and thinkers of the time, including the philosopher [[Socrates]], to her house, which became an intellectual centre in Athens. Socrates described her as a skilled teacher of rhetoric. She was the companion of the statesman [[Pericles]], with whom she had a son, [[Pericles the Younger]], but the full details of the couple's marital status are unknown. Aspasia is mentioned in the writings of [[Plato]], [[Aristophanes]], [[Xenophon]], and others. |

|||

==Sources== |

|||

Although she spent most of her adult life in Greece, few details of her life are fully known. The ancient sources about Aspasia's life are scant, of often of questionable reliability and contradictory, with some portraying her as an intellectual luminary, [[rhetorician]], and [[philosopher]] and others portraying her as a [[procuring (prostitution)|brothel keeper]] or [[hetaera]]. Aspasia's role in history provides crucial insight into understanding the [[women of ancient Greece]]. Very little is known about women from her time period. One scholar stated that, "To ask questions about Aspasia's life is to ask questions about half of humanity."<ref name=Henry9>M. Henry, ''Prisoner of History'', 9</ref> |

|||

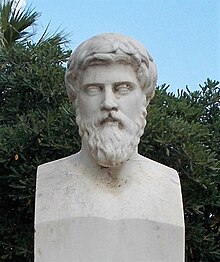

[[File:Plutarch of Chaeronea-03 (cropped).jpg|thumb|right|Statue of Plutarch, the main ancient source for the life of Aspasia]] |

|||

{{blockquote|We must make do with the sources that mention her, even when they fundamentally distort reality.|source=Nicole Loraux, "Aspasia, Foreigner, Intellectual".{{sfn|Loraux|2021|p=14}}}} |

|||

Aspasia was an important figure – and the most important woman – in the history of fifth-century Athens,{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=3}} and is one of the women from the Greco-Roman world with the most substantial biographical traditions.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=6}} The earliest literary sources to mention Aspasia, written during her lifetime, are from [[Old Comedy|Athenian comedy]],{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=6}} and in the fourth century BC she appears in [[Socratic dialogue]]s.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=29}} After the fourth century, she appears only in brief mentions of complete texts, or in fragments whose full context is now lost,{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=57}} until the second century AD, when [[Plutarch]] wrote his ''Life of Pericles'', the longest and most complete ancient biographical treatment of Aspasia.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=9}} Modern biographies of Aspasia are dependent on Plutarch,{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=68}} despite his writing nearly seven centuries after her death.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=9}} |

|||

It is difficult to draw any firm conclusions about the real Aspasia from any of these sources: as Robert Wallace puts it, "for us Aspasia herself possesses and can possess almost no historical reality".{{sfn|Wallace|1996}} Aside from her name, father's name, and place of birth, Aspasia's biography is almost entirely unverifiable, and the ancient writings about her are frequently more of a projection of their own (without exception male) preconceptions than they are historical fact.{{sfn|Azoulay|2014|pp=104–5}} Madeleine Henry's full-length biography covers what is known of Aspasia's life in only nine pages.{{sfn|Pomeroy|1996|p=648}} |

|||

==Origin and early years== |

|||

Aspasia was born in the [[Ionia]]n Greek city of [[Miletus]] (in the modern province of [[Aydın]], Turkey). Little is known about her family except that her father's name was Axiochus. It is apparent that she belonged to a wealthy family, because only the well-to-do could have afforded the excellent education that she received. Her name, which means "the desired one", was not likely to be her given name.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Encyclopedia of women in the ancient world|last=Salisbury|first=Joyce|author-link= Joyce E. Salisbury |date=2001|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=1576070921|oclc=758191338}}</ref> |

|||

==Life== |

|||

Some ancient sources claim that she was a [[Caria]]n [[prisoner-of-war]] turned [[slave]]; these statements are generally regarded as false.{{efn|name=fn2|According to [[Debra Nails]], Professor of Philosophy at [[Michigan State University]], if Aspasia had not been a free woman, the decree to legitimize her son with Pericles and the later marriage to Lysicles (Nails assumes that Aspasia and Lysicles were married) would almost certainly have been impossible.<ref name="Nails58-59" /> |

|||

===Early life=== |

|||

}}<ref name="Lendering">J. Lendering, [https://www.livius.org/articles/person/aspasia/ Aspasia of Miletus] livius.org</ref> |

|||

Aspasia was born, probably no earlier than 470 BC,{{efn|This date is derived from the birthdates of Aspasia's two sons: Pericles the Younger between 452 and 440, and Poristes in 428 BC.{{sfn|Bicknell|1982|pp=244–5}} However, some scholars doubt the existence of Aspasia's second son; in that case, Aspasia could have been born some time earlier than 470.{{sfn|Wallace|1996}}}}{{sfn|Bicknell|1982|p=245}} in the [[Ionia|Ionian]] Greek city of [[Miletus]]{{efn|[[Athenaeus]] quotes [[Heraclides of Pontus]] as saying that Aspasia came from Megara; this apparently derives from a misunderstanding of [[Aristophanes]]' ''Acharnians''.{{sfn|Kennedy|2014|p=75}}}} (in modern [[Aydın Province]], Turkey), the daughter of a man called Axiochus.{{sfn|Azoulay|2014|p=104}} A [[scholiast]] on [[Aelius Aristides]] wrongly claims that Aspasia was a [[Caria]]n prisoner of war and a slave;{{sfn|Nails|2000|p=59}} this is perhaps due to confusion with the concubine of [[Cyrus the Younger]], also called Aspasia.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=132|loc=n. 1}} The circumstances surrounding Aspasia's move to Athens are unknown.{{sfn|Nails|2000|p=59}} One theory, first put forward by Peter Bicknell based on a fourth-century tomb inscription, suggests that Alcibiades of Scambonidae, the grandfather of the famous [[Alcibiades]], married Aspasia's sister while he was in exile in Miletus following his [[ostracism]], and Aspasia went with him when he returned to Athens.{{sfn|Nails|2000|p=59}} Bicknell speculates that this was motivated by the death of Aspasia's father Axiochus in the upheaval in Miletus following its secession from the [[Delian League]] in 455/4 BC.{{sfn|Bicknell|1982|p=247}} |

|||

===Life in Athens=== |

|||

It is not known under what circumstances she first traveled to Athens. The discovery of a fourth-century grave inscription that mentions the names of Axiochus and Aspasius has led historian Peter K. Bicknell to attempt a reconstruction of Aspasia's family background and Athenian connections. His theory connects her to Alcibiades II of Scambonidae (grandfather of the famous [[Alcibiades]]), who was [[ostracism|ostracized]] from Athens in 460 BC and may have spent his exile in Miletus.<ref name="Nails58-59" /> Bicknell conjectures that, following his exile, the elder Alcibiades went to Miletus, where he married a daughter of a certain Axiochus. Alcibiades apparently returned to Athens with his new wife and her younger sister, Aspasia. Bicknell argues that the first child of this marriage was named [[Axiochus (Alcmaeonid)|Axiochus]] (uncle of the famous Alcibiades) and the second child was named Aspasios. He also maintains that Pericles met Aspasia through his close connections with the Alcibiades household.<ref name="Bicknell">P.J. Bicknell, ''Axiochus Alkibiadou, Aspasia and Aspasios.''</ref> |

|||

According to the conventional understanding of Aspasia's life, Aspasia worked as a courtesan and then ran a brothel.{{sfn|Kennedy|2014|p=75}} Some scholars have challenged this view. Peter Bicknell notes that the "pejorative epithets applied to her by comic dramatists" are unreliable.{{sfn|Bicknell|1982|p=245}} Madeleine Henry argued in her biography of Aspasia that "we are not required to believe that Aspasia was a whore because a comic poet says she was", and that the portrayal of Aspasia as involved in the sex trade should "be looked upon with great suspicion".{{sfn|Henry|1995|pp=138–9|loc=n. 9}} Despite these challenges to the traditional narrative, many scholars continue to believe that Aspasia worked as a courtesan or madam.{{sfn|Kennedy|2014|pp=75; 87|loc=n. 1}} Konstantinos Kapparis argues that the kinds of comic attacks made on Aspasia would not have been acceptable to make about a respectable woman, and that it is therefore likely that Aspasia did have a history as a sex-worker before she began her relationship with Pericles.{{sfn|Kapparis|2018|p=104}} Whether or not Aspasia worked as a courtesan, her later life, in which she apparently achieved some degree of power, reputation, and independence, has similarities to the lives of other prominent ''hetaerae'' such as [[Phryne]].{{sfn|Kapparis|2018|p=393}} |

|||

[[File:Pericles Pio-Clementino Inv269 n2.jpg|thumb|right|Bust of Pericles]] |

|||

==Life in Athens== |

|||

In Athens, Aspasia met and began a relationship with the statesman [[Pericles]]. It is uncertain how they met;{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=13}} if Bicknell's thesis is correct then she may have met him through his connection to Alcibiades' household.{{sfn|Bicknell|1982|p=247}} Rebecca Futo Kennedy speculates that when [[Cleinias]], the son of the elder Alcibiades, died at the [[Battle of Coronea (447 BC)|Battle of Coronea]], Pericles may have become the [[kurios]] (guardian) of Aspasia.{{sfn|Kennedy|2014|p=77}} Aspasia's relationship with Pericles began some time between 452 and 441.{{efn|Pericles and Aspasia's relationship began after Pericles' first marriage, which cannot have ended before 452/1, the earliest possible birthdate for Pericles' second legitimate son, [[Paralus and Xanthippus|Paralus]]. It must have begun by 441/0, the latest possible date for the conception of Pericles the Younger, who was at least 30 in 410/9 when he was [[hellenotamias]].{{sfn|Bicknell|1982|pp=243–4}}}}{{sfn|Bicknell|1982|pp=243–4}} The exact nature of Pericles and Aspasia's relationship is disputed. Ancient authors variously portrayed her as a prostitute, his concubine, or his wife.{{sfn|Azoulay|2014|p=105}} Modern scholars are also divided. Rebecca Futo Kennedy argues that they were married;{{sfn|Kennedy|2014|pp=17; 77}} Debra Nails describes Aspasia as "the ''de facto'' wife of Pericles";{{sfn|Nails|2000|p=59}} Madeleine Henry believes that Pericles' citizenship law of 451/0 made marriage between an Athenian and a [[metic]] illegal, and suggests a quasi-marital ''[[pallake|pallakia]]'' ("concubinage") enforced by contract;{{sfn|Henry|1995|pp=13–14}} and Sue Blundell describes Aspasia as a [[hetaira]] ("courtesan") and mistress of Pericles.{{sfn|Blundell|1995|p=148}} |

|||

[[Image:AspasiaAlcibiades.jpg|thumb|upright=1.35|left|''Socrates seeking Alcibiades in the house of Aspasia'', 1861, by [[Jean-Léon Gérôme]] (1824–1904)]] |

|||

Aspasia and Pericles had a son, [[Pericles the Younger]], born by 440 BC.{{efn|Pericles the Younger was at least 30 in 410/9, when he was hellenotamias, and therefore was born no later than 440/39.{{sfn|Bicknell|1982|p=243}}}}{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=13}} At the time of Pericles the Younger's birth, Pericles had two legitimate sons, [[Paralus and Xanthippus]]. In 430/29, after the death of his two elder sons, Pericles proposed an amendment to his citizenship law of 451/0 which would have made Pericles the Younger able to become a citizen and inherit. Though many scholars believe that this was specifically for Pericles, some have suggested that a more general exception was introduced, in response to the effect of the [[Plague of Athens]] and [[Peloponnesian War]] on citizen families.{{sfn|Kennedy|2014|p=17}} |

|||

According to the disputed statements of the ancient writers and some modern scholars, in Athens Aspasia became a [[hetaera]] and ran a [[brothel]].{{efn|Henry regards as a slander the reports of ancient writers and comic poets that Aspasia was a brothel keeper and a harlot. Henry argues that these comic sallies aimed at ridiculing the leading citizen of Athens, Pericles, and were based on the fact that, by his own citizenship law, Pericles was prevented from marrying Aspasia and so had to live with her in an unmarried state.<ref name="H138-139">M. Henry, ''Prisoner of History'', 138–139</ref> For these reasons historian Nicole Loraux questions even the testimony of ancient writers that Aspasia was a hetaera or a courtesan.<ref name="Loraux">N. Loraux, ''Aspasie, l'étrangère, l'intellectuelle'', 133–164</ref> Fornara and Samons also dismiss the fifth-century tradition that Aspasia was a harlot and managed houses of ill-repute.<ref name="Fornara" />}}<ref name="Ar523">Aristophanes, ''Acharnians'', [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0240&layout=&loc=523 523–527]</ref><ref name="Just144">R. Just, ''Women in Athenian Law and Life", 144</ref> Hetaerae were professional high-class entertainers, as well as [[courtesans]]. Besides displaying physical beauty, they differed from most Athenian women in being educated (often to a high standard, as Aspasia evidently was), having independence, and [[Economy of ancient Greece#Taxation|paying taxes]].<ref name="Br">{{cite encyclopedia|title=Aspasia|encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica|year=2002}}</ref><ref name="Southall">A. Southall, ''The City in Time and Space'', 63</ref> They were the nearest thing perhaps to liberated women; and Aspasia, who became a prominent figure in Athenian society, could be an obvious example.<ref name="Br" /><ref name="Arkins">B. Arkins, [http://ancienthistory.about.com/gi/dynamic/offsite.htm?zi=1/XJ&sdn=ancienthistory&zu=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ucd.ie%2Fclassics%2Fclassicsinfo%2F94%2FArkins94.html Sexuality in Fifth-Century Athens]</ref> According to [[Plutarch]], Aspasia was compared to the famous [[Thargelia (person)|Thargelia]], another renowned Ionian hetaera of ancient times.<ref name="Pl24">Plutarch, ''Pericles'', [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0182;query=chapter%3D%23169;layout=;loc=Per.%2023.1/ XXIV]</ref> |

|||

According to Plutarch, Aspasia was prosecuted for ''[[asebeia]]'' (impiety) by the comic poet [[Hermippus]].{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=15}} She was supposedly defended by Pericles and acquitted.{{sfn|Nails|2000|p=61}} Many scholars have questioned whether this trial ever took place, suggesting that the tradition derives from a fictional trial of Aspasia in a play by Hermippus.{{sfn|Wallace|1996}} Vincent Azoulay compares the trial of Aspasia to those of [[Phidias]] and [[Anaxagoras]], both also connected to Pericles, and concludes that "none of the trials for impiety involving those close to Pericles is attested with certainty".{{sfn|Azoulay|2014|pp=124–6}} |

|||

Nonetheless, as a non-Athenian woman, Aspasia was less bound by the traditional restraints that largely confined Athenian wives to their homes, and appears to have taken the opportunity to participate in the public life of the city. She became the companion of the statesman Pericles around 445 BC. After he divorced his first wife (perhaps c. 450 BC), Aspasia began to live with him. |

|||

In 429 BC, Pericles died. According to ancient sources, Aspasia then married another politician, [[Lysicles (5th century BC)|Lysicles]], and gave birth to another son, Poristes.{{sfn|Henry|1995|pp=9–10; 43}} As "Poristes" is not otherwise known as a name – it means "supplier" or "provider",{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=43}} and was a euphemism for "thief"{{sfn|Kennedy|2014|p=92|loc=n.52}} – some scholars have argued that the name comes from a misunderstanding of a joke in a comedy.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=43}}{{sfn|Nails|2000|p=61}}{{sfn|Kennedy|2014|p=77}} Henry doubts whether Aspasia had a child with Lysicles,{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=43}} and Kennedy questions whether she married Lysicles at all.{{sfn|Kennedy|2014|p=77}} Pomeroy, however, suggests that Poristes' unusual name may have been chosen by Lysicles for political reasons, to draw attention to his providing for the people of Athens.{{sfn|Pomeroy|1996|p=649}} Lysicles died a year after Pericles, in 428, and nothing is recorded of Aspasia's life after this point.{{sfn|Nails|2000|p=59}} It is unknown where or when she died,{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=17}} though the structure of [[Aeschines of Sphettos|Aeschines]]' dialogue ''Aspasia'' implies that it was before the death of [[Socrates]] in 399.{{sfn|Taylor|1955|p=41}} |

|||

Their marital status is disputed by later historians.{{efn|Fornara and Samons take the position that Pericles married Aspasia, but his citizenship law declared her to be an invalid mate.<ref name="Fornara" /> Wallace argues that if Pericles married Aspasia, he was continuing a distinguished Athenian aristocratic tradition of marrying well-connected foreigners.<ref name="Wallace" /> Henry believes that Pericles was prevented by his own citizenship law from marrying Aspasia and so had to live with her in an unmarried state.<ref name="H138-139" /> On the basis of a comic passage Henry suggests that Aspasia's status was that of a ''pallake'', namely a [[concubine]] or de facto unmarried wife.<ref name="H21">M. Henry, ''Prisoner of History'', 21</ref> William Smith suggests that Aspasia's relationship with Pericles was "analogous to the left-handed marriages of modern princes".<ref>W. Smith, ''A History of Greece'', 261</ref> However, historian [[Arnold W. Gomme]] underscores that "his contemporaries spoke of Pericles as married to Aspasia".<ref name="Gomme">[[A. W. Gomme]], ''Essays in Greek History & Literature'', 104</ref> |

|||

}}<ref name="Ostwald310">M. Ostwald, ''Athens as a Cultural Center'', 310</ref> |

|||

==Legacy== |

|||

Their son, [[Pericles the Younger]], must have been born by 440 BC. Aspasia would have been quite young at the time of his birth, as she went on to bear another child by Lysicles c. 428 BC.<ref name="Stadter239">P.A. Stadter, ''A Commentary on Plutarch's Pericles'', [https://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=96911382 239]</ref> |

|||

===Ancient reception=== |

|||

In the classical period, two schools of thought developed around Aspasia. One tradition, deriving from Old Comedy, emphasises her influence over Pericles and her involvement in the sex trade; the other, which can be traced back to fourth-century philosophy, concentrates on her intellect and rhetorical skill.{{sfn|Fornara|Samons|1991|pp=163–4}} |

|||

====Comic tradition==== |

|||

In social circles, Aspasia was noted for her ability as a [[conversationalist]] and adviser rather than merely an object of physical beauty.<ref name="Just144" /> Several centuries later, Plutarch wrote that friends of Socrates brought their wives to hear her converse, 'despite her immoral life'.{{efn|According to Kahn, stories such as Socrates' visits to Aspasia, along with his friends' wives and Lysicles' connection with Aspasia, are not likely to be historical. He believes that Aeschines was indifferent to the historicity of his Athenian stories and that these stories must have been invented at a time when the date of Lysicles' death had been forgotten, but his occupation still remembered.<ref name="Vander96-98" /> |

|||

The only surviving ancient sources to discuss Aspasia contemporary with her life are from comedy. The surviving comic tradition about Aspasia – unlike her male contemporaries – focuses on her sexuality.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=19}} [[Aristophanes]], the only writer of Old Comedy for whom complete works survive, refers to Aspasia only once in his surviving corpus, in ''[[Acharnians]]''.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=25}} In a passage parodying the beginning of [[Herodotus]]' ''Histories'',{{sfn|Henry|1995|pp=25–6}} Aristophanes jokes that the [[Megarian decree]] was retaliation for the kidnapping of two ''[[pornai]]'' from Aspasia.{{sfn|Kennedy|2014|p=77}} A similar charge, attributed by Plutarch to [[Duris of Samos]], that Aspasia was responsible for Athens' involvement in the [[Samian War]], may have derived from this.{{efn|Alternatively, Loraux suggests that Aristophanes based his joke on an unknown earlier comic author, who had already implicated Aspasia in starting the Samian War.{{sfn|Loraux|2021|p=26}}}}{{sfn|Wallace|1996}} The mention of Aspasia's ''pornai'' in ''Acharnians'' is also the earliest known instance of the tradition that she worked as a brothel-keeper.{{sfn|Podlecki|1998|p=116}} |

|||

}}<ref name="Pl24" /><ref name="Adams75-76">H. G. Adams, ''A Cyclopaedia of Female Biography'', 75–76</ref> |

|||

Outside of Aristophanes, mentions of Aspasia are known from the surviving fragments of [[Cratinus]] and [[Eupolis]].{{sfn|Henry|1995|pp=20–4}} In a fragment of Cratinus' ''Cheirons'', Aspasia is described as "Hera-Aspasia, a dog-eyed concubine".<ref>Cratinus, fr. 259 K-A</ref> Eupolis mentions Aspasia by name in three surviving fragments. In ''Proslapatians'', she is compared to [[Helen of Troy]] – like Aspasia, blamed for starting a war – and in ''Philoi'' to [[Omphale]], who owned [[Herakles]] as a slave.{{sfn|Henry|1995|pp=22–3}} Eupolis also alluded to Aspasia in ''Demes'', where Pericles, having been brought back from the dead, asks after his son; he is informed that he is alive, but is ashamed of having a ''porne'' as a mother.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=24}} Aspasia is also known to have been mentioned by [[Callias (comic poet)|Kallias]], though the scholion to Plato's ''[[Menexenus (dialogue)|Menexenus]]'' which reports this is garbled and it is uncertain what Kallias said about her.{{sfn|Podlecki|1998|p=112}} She may also have appeared in a play by Hermippus – this is possibly the source of the anecdote told by Plutarch that Aspasia was prosecuted by him for ''asebeia'' and for supplying free-born women for Pericles to have sex with.{{sfn|Azoulay|2014|p=102}} Later authors to follow the comic tradition in focusing on Aspasia's sexuality and improper influence over Pericles, for example in [[Clearchus of Soli|Clearchus']] ''Erotika''.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=66}} |

|||

==Personal and judicial attacks== |

|||

Her relationship with Pericles and her subsequent political influence aroused many reactions. Pericles was acclaimed by [[Thucydides]], a contemporary historian, as "the first citizen of Athens".<ref name="Thuc65">Thucydides, [[s:History of the Peloponnesian War/Book 2#2:65|2.65]]</ref><!--All quotes [[WP:FULLCITE]]--> Pericles turned the [[Delian League]] into an Athenian empire and led his countrymen during the first two years of the Peloponnesian War. The period during which he led Athens, roughly from 461 to 429 BC, is sometimes known as the "[[Age of Pericles]]". However, although they were influential, Pericles, Aspasia, and their friends were not immune from attack, as preeminence in [[Athenian democracy|democratic Athens]] was not equivalent to absolute rule.<ref name="For2">Fornara-Samons, ''Athens from Cleisthenes to Pericles'', [http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft2p30058m&chunk.id=d0e2016&toc.depth=1&toc.id=d0e2016&brand=eschol/ 30]</ref> |

|||

====Philosophical tradition==== |

|||

[[Donald Kagan]], a [[Yale University|Yale]] historian, believes that Aspasia was particularly unpopular in the years immediately following the [[Samian War]].<ref name="Kagan197">D. Kagan, ''The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War'', 197</ref> In 440 BC, [[Samos Island|Samos]] was at war with Miletus over [[Priene]], an ancient city of [[Ionia]] in the foothills of [[Mycale]]. Worsted in the war, the Milesians came to Athens to plead their case against the Samians.<ref name="Th115">Thucydides, I, [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0200&layout=&loc=1.115.1 115]</ref> When the Athenians ordered the two sides to stop fighting and submit the case to arbitration at Athens, the Samians refused. In response, Pericles passed a decree dispatching an expedition to Samos.<ref name="Pl25">Plutarch, ''Pericles'', [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0182;query=chapter%3D%23170;layout=;loc=Per.%2024.1/ XXV]</ref> The campaign proved to be difficult and the Athenians had to endure heavy casualties before Samos was defeated. Centuries later, according to Plutarch, it was thought that Aspasia, who came from Miletus, had been responsible for the Samian War because Pericles had decided against and attacked Samos to gratify her.<ref name="Pl24" /> |

|||

[[File:The Debate Of Socrates And Aspasia.jpg|thumb|right|In a tradition that can be traced back to the fourth century BC, Aspasia was a skilled rhetorician. In this painting by [[Nicolas-André Monsiau]], she speaks while Socrates and Pericles listen attentively.]] |

|||

In the fourth century, four philsophers are known to have written Socratic dialogues which feature Aspasia. Those by [[Antisthenes]] and Plato portray her negatively, in a way resembling her portrayal in comedy; Aeschines and [[Xenophon]] show her in a more positive light.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=30}} In the dialogues by Plato, Xenophon, and Aeschines, Aspasia is portrayed as an educated, skilled rhetorician, and a source of advice for marital concerns.{{sfn|Kennedy|2014|p=151}} In the Hellenistic and Roman periods, some authors followed Aspasia's more positive portrayal in Socratic literature, distancing her from prostitution and situating her in a tradition of wise women. [[Didymus Chalcenterus]] wrote about exceptional women in history in his ''Symposiaka'', downplaying her sexuality but noting her influence on Socrates' philosophy and Pericles' rhetoric.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=66}} In Rome, [[Cicero]] and [[Quintillian]] used the conversation between Aspasia and Xenophon in Aeschines' dialogue as a good example of ''inductio''.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=67}} |

|||

===Modern reception=== |

|||

{{quote box |

|||

|align=right |

|||

|width=40% |

|||

|border=1px |

|||

|quote= "Thus far the evil was not serious and we were the only sufferers. But now some young drunkards go to Megara and carry off the courtesan Simaetha; the Megarians, hurt to the quick, run off in turn with two harlots of the house of Aspasia; and so for three whores Greece is set ablaze. Then Pericles, aflame with ire on his Olympian height, let loose the lightning, caused the thunder to roll, upset Greece and passed an edict, which ran like the song, That the Megarians be banished both from our land and from our markets and from the sea and from the continent." |

|||

|source= Lines [http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0019.tlg001.perseus-eng1:496-540 523–533] from ''The Acharnians'', a [[Greek comedy|comedic play]] by [[Aristophanes]]<!--who was accused of slander by [[Plato]]-->}} |

|||

Aspasia's earliest post-classical portrayal is in the letters of [[Héloïse]] to [[Abelard]].{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=83}} Héloïse cites Aspasia's conversation with Xenophon and his wife in Aeschines' dialogue, which she probably knew through Cicero's reference to it, and proposes Aspasia as an example for how she should live her own life.{{sfn|Henry|1995|pp=83–4}} |

|||

According to some later accounts, before the eruption of the [[Peloponnesian War]] (431–404 BC), Pericles, some of his closest associates (including the philosopher [[Anaxagoras]] and sculptor [[Phidias]]), and Aspasia faced a series of personal and legal attacks. Aspasia, in particular, was accused in comedy of corrupting the women of Athens in order to satisfy Pericles' perversions.{{efn|Kagan estimates that, if a trial of Aspasia happened, "we have better reason to believe that it happened in 438 than at any other time".<ref name="Kagan197" />}} Writing centuries later, Plutarch wrote that she was put on trial for [[asebeia]] (impiety), with the comic poet [[Hermippus]] as prosecutor.{{efn|According to James F. McGlew, Professor at Iowa State University, it is not very likely that the charge against Aspasia was made by Hermippus. He believes that "Plutarch or his sources have confused the law courts and theater".<ref name="Glew53">J.F. McGlew, ''Citizens on Stage'', 53</ref> |

|||

}}<ref name="Pl32">Plutarch, ''Pericles'', [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0007.tlg012.perseus-eng1:32.1 XXXII]</ref> The historical nature of the accounts about these events is disputed; it is unlikely that a non-Athenian woman could be subject to legal charges of this kind (although her protector or ''kurios'', in this case Pericles, might be), and no harm came to her as a result.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Filonik|first=Jakub|date=2013|title=Athenian impiety trials: a reappraisal|url=http://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/Dike/article/view/4290|journal=Dike|volume=16|issue=16|pages=26–33|doi=10.13130/1128-8221/4290}}</ref> |

|||

In the late medieval and early modern periods, Aspasia appeared in several catalogues, a fashionable genre at the time. She was included in three "medallion books", with an imagined portrait and a brief biography. The first of these was [[Guillaume Rouille]]'s ''Promptuarium Iconum'', which derives its depiction of Aspasia from Plutarch and focuses on her relationship with Pericles;{{sfn|Henry|1995|pp=87–8}} In [[Giovanni Angelo Canini]]'s ''Iconografia'', Aspasia is depicted wearing a helmet and shield.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=89}} Aspasia also featured in two catalogues of women in this period as a teacher and philosopher; in [[Arcangela Tarabotti]]'s ''Tirannia Paterna'', which portrays her as a teacher of rhetoric, and [[Gilles Ménage]]'s ''Historia Mulierum Philosopharum'', in which Aspasia is described as teaching rhetoric to Pericles and Socrates, and philosophy to Socrates.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=88–9}} |

|||

In ''[[The Acharnians]]'', [[Aristophanes]] blames Aspasia for the Peloponnesian War. He claims that the [[Megarian decree]] of Pericles, which excluded [[Megara]] from trade with Athens or its allies, was retaliation for prostitutes being kidnapped from the house of Aspasia by Megarians.<ref name="Ar523" /> Aristophanes' portrayal of Aspasia as responsible, from personal motives, for the outbreak of the war with [[Sparta]] may reflect memory of the earlier episode involving Miletus and Samos.<ref name="Powel261">A. Powell, ''The Greek World'', 259–261</ref> Plutarch reports also the taunting comments of other comic poets, such as [[Eupolis]] and [[Cratinus]].<ref name="Pl24" /> According to Podlecki, [[Douris (tyrant)|Douris]] appears to have propounded the view that Aspasia instigated both the Samian and Peloponnesian Wars.<ref name="Podlecki126">A.J. Podlecki, ''Pericles and his Circle'', 126</ref> |

|||

[[File:Aspasia painting.jpg|thumb|right|[[Marie Bouliard]]'s 1794 portrait of Aspasia]] |

|||

Aspasia was labeled the "New [[Omphale]]", "[[Deianira]]",{{efn|Omphale and Deianira were respectively the [[Lydia]]n queen who owned [[Heracles]] as a slave for a year and his long-suffering wife. [[Theatre of ancient Greece|Athenian dramatists]] took an interest in Omphale from the middle of the 5th century. The comedians parodied Pericles for resembling a Heracles under the control of an Omphale-like Aspasia.<ref name="Stadter240">P.A. Stadter, '' A Commentary on Plutarch's Pericles'', [https://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=96911382 240]</ref> Aspasia was called "Omphale" in the ''Kheirones'' of Cratinus or the ''Philoi'' of Eupolis.<ref name="Powel261" /> |

|||

By the eighteenth century, Aspasia was widely enough known to be included in dictionaries and encyclopedias, where depictions of her were largely based off of Plutarch.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=89}} In 1736, [[Jean Leconte de Bièvre]] published a ''Histoire de deux Aspasies'', also based on Plutarch's depiction, which portrayed Aspasia as an educated woman and Pericles' teacher as well as his wife.{{sfn|Henry|1995|pp=89–90}} The eighteenth century also saw the first known image of Aspasia to be created by a woman, [[Marie Bouliard]]'s ''Aspasie''.{{sfn|Henry|1995|pp=91–2}} The painting depicts Aspasia with one breast bared, looking into a handheld mirror and with a scroll in her other hand. Though the bare breast references the eroticised traditions surrounding Aspasia, Madeleine Henry argues that the portrait differs from more pornographic depictions of women, with Aspasia looking into the mirror rather than out at the viewer, and holding a scroll rather than a cosmetic object such as a comb.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=93}} |

|||

}} "[[Hera]]"{{efn| Αs wife of the "Olympian" Pericles.<ref name="Stadter240" /> Ancient Greek writers call Pericles "Olympian", because he was "thundering and lightning and exciting Greece" and carrying the weapons of Zeus when orating.<ref name="ArDi">Aristophanes, ''Acharnians'', [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0240;query=card%3D%2326;layout=;loc=541/ 528–531] and Diodorus, XII, [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0060.tlg001.perseus-eng1:12.40.6 40]</ref> |

|||

}} and "[[Helen of Troy|Helen]]".{{efn| Cratinus (in ''Dionysalexandros'') assimilates Pericles and Aspasia to the "outlaw" figures of Paris and Helen; just as Paris caused a war with Spartan [[Menelaus]] over his desire for Helen, so Pericles, influenced by the foreign Aspasia, involved Athens in a war with Sparta.<ref name="Padilla">M. Padilla, [http://facstaff.unca.edu/drohner/awomlinks/artherktrach1.htm#_ednref17 "Labor's Love Lost: Ponos and Eros in the Trachiniae"] paper presented at the 95th Annual Meeting of the Classical Association of the Middle West and South, Cleveland, Ohio, April 14–17, 1999 {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120310105601/http://facstaff.unca.edu/drohner/awomlinks/artherktrach1.htm#_ednref17 |date=March 10, 2012 }}</ref> Eupolis also called Aspasia Helen in the ''Prospaltoi''.<ref name="Stadter240" /> |

|||

}}<ref name="Fornara">Fornara-Samons, ''Athens from Cleisthenes to Pericles'', [http://content.cdlib.org/xtf/view?docId=ft2p30058m&chunk.id=d0e9775&toc.depth=1&toc.id=&brand=eschol/ 162–166]</ref> Further attacks on Pericles' relationship with Aspasia are reported by [[Athenaeus]].<ref name="Deipn533">Athenaeus, ''Deipnosophistae'', 533c–d</ref> Even Pericles' own son, Xanthippus, who had political ambitions, readily criticised his father about his domestic affairs.<ref name="Pl26">Plutarch, ''Pericles'', [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0182&layout=&loc=Per.+31.1 XXXVI]</ref> |

|||

In the nineteenth century, Plutarch's narrative dominated the interpretation of Aspasia in both novels and paintings.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=96}} In the visual arts, the sexualised side of Aspasia was represented by [[Jean-Léon Gérôme]]'s painting ''Socrates Seeking Alcibiades in the House of Aspasia'', but this pornographised representation was relatively uncommon.{{sfn|Geraths|Kennerly|2016|p=198}} [[Honoré Daumier]]'s lithograph of ''Socrates at the House of Aspasia'' depicts as an Aspasia identified in its caption as a "[[lorette (prostitution)|lorette]]", an ambiguous social position which referred to "loose, vulgar or 'liberated' women".<ref>{{harvnb|Jordan|2012|p=72}}, quoted in {{harvnb|Geraths|Kennerly|2016|p=205}}</ref> Other artists of the period depicted an Aspasia active in public life, and interacting with the most renowned men of the period. In [[Henry Holiday]]'s painting of ''Aspasia on the Pnyx'', she is shown with another woman at the site of the [[ecclesia (ancient Greece)#The ekklesia of Athens|Athenian assembly]], the cente of male public space in the city,{{sfn|Geraths|Kennerly|2016|p=206}} while in two paintings by [[Nicolas-André Monsiau]] she is shown at the centre of discussions with celebrated Athenian intellectuals and politicians.{{sfn|Geraths|Kennerly|2016|pp=200–2}} In ''Socrates and Aspasia'', she converses with Socrates and Pericles; in ''Aspasia in Conversation with the Most Illustrious Men of Athens'', [[Euripides]], [[Sophocles]], Plato, and Xenophon are also among those included.{{sfn|Geraths|Kennerly|2016|p=202}} In both of these paintings, Aspasia is speaking and commanding the attention of these men.{{sfn|Geraths|Kennerly|2016|pp=201–2}} Melissa Ianetta argues that [[Germaine de Staël]]'s novel ''Corinne'' models its heroine after Aspasia, placing her in the same tradition of feminine rhetorical skill.{{sfn|Ianetta|2008}} |

|||

==Later years and death== |

|||

[[File:Pericles Pio-Clementino Inv269 n2.jpg|thumb|[[Pericles with the Corinthian helmet|Bust of Pericles]], marble Roman copy after a Greek original from c. 430 BC]] |

|||

In 429 BC, during the [[Plague of Athens]], Pericles witnessed the death of his sister and of both his legitimate sons from his first wife, [[Paralus and Xanthippus]]. With his morale undermined, he wept and not even Aspasia's companionship could console him. Just before his own death, the Athenians allowed a change in the citizenship law of 451 BC that made his half-Athenian son with Aspasia, Pericles the Younger, a citizen and legitimate heir,<ref name="Pl37">Plutarch, ''Pericles'', ''Plutarch's Lives'' with an English Translation by. Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. London. William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. 2 [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0182;query=chapter%3D%23182;layout=;loc=Per.%2036.1/ XXXVII]</ref> a decision all the more striking in considering that Pericles was the one to have proposed the law confining citizenship to those of Athenian parentage on both sides.<ref name="Smith">W. Smith, ''A History of Greece'', 271</ref> Pericles died of the plague in the autumn of 429 BC. |

|||

Meanwhile, the authors [[Walter Savage Landor]] and [[Elizabeth Lynn Linton]] portrayed Aspasia as a good Victorian wife to Pericles in their novels ''Pericles and Aspasia'' and ''Amymone: A Romance of the Days of Pericles''.{{sfn|Henry|1995|pp=99–102}} [[Laurence Alma-Tadema]]'s painting ''Phidias and the Frieze of the Parthenon'' also shows Aspasia as a respectable companion to men.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=103}} By contrast, [[Robert Hamerling]]'s novel ''Aspasia'' showed her as a proto-feminist with far more agency than these romanticised accounts.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=106}} |

|||

Plutarch later cites [[Aeschines Socraticus]], who wrote a [[Dialogue|dialog]]ue on Aspasia (now lost), to the effect that after Pericles's death, Aspasia lived with Lysicles, an Athenian [[strategos]] (general) and democratic leader, with whom she had another son; and that she made him the first man at Athens.{{efn|name=fn2}}<ref name="Pl24" /> Lysicles was killed in action on an expedition to levy subsidies from allies<ref name="Th3.19">Thucydides, [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0003.tlg001.perseus-eng3:3.19.2 III, Chapter 19 Section 2]</ref> in 428 BC.<ref>N.G.L Hammond, H.H. Scullard (eds.), ''The Oxford Classical Dictionary'' 2nd ed., 131</ref> That dialogue ended with the death of Lysicles.<ref name="Adams75-76" /> |

|||

The twentieth century saw both interest in Aspasia separately from her relationships with men, and on the other hand more prurient concern with her sexuality.{{sfn|Henry|1995|pp=113–4}} The former strand of Aspasia's reception saw the Latvian author, feminist, and politician [[Elza Rozenberga]], who took the pseudonym Aspazija, model her campaigning for women's rights after what she saw as Aspasia's example.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=114}} Aspasia was also taken on as a feminist role-model by [[Judy Chicago]], who included her as one of the thirty-nine women given a place in her artwork ''[[The Dinner Party]]''.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=121}} Recent novels have tended towards the more explicitly sexualised portrayal of Aspasia, including ''Achilles His Armour'' by the classicist [[Peter Green (historian)|Peter Green]],{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=117}} Madelon Dimont's ''Darling Pericles'',{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=117}} and [[Taylor Caldwell]]'s ''Glory and Lightning'', in which Aspasia is raised as a courtesan.{{sfn|Henry|1995|p=119}} |

|||

It is not known whether Aspasia was alive when her son, Pericles the Younger, was elected general or when he was executed after the [[Battle of Arginusae]]. The time of her death that most historians give (c. 401–400 BC) is based on the assessment that Aspasia died before the execution of Socrates in 399 BC, a chronology that is implied in the structure of Aeschines' ''Aspasia''.<ref name="Nails58-59" /><ref name="Taylor41" /> |

|||

==References in philosophical works== |

|||

===Ancient philosophical works=== |

|||

Aspasia appears in the philosophical writings of [[Plato]], [[Xenophon]], [[Aeschines Socraticus]], and [[Antisthenes]]. Some scholars argue that Plato was impressed by her [[intelligence]] and [[wit]] and based his character [[Diotima of Mantinea|Diotima]] in the ''[[Symposium (Plato)|Symposium]]'' on her. Others suggest that Diotima was a historical figure and unrelated to Aspasia.<ref name="Wider1986">K. Wider, "Women philosophers in the Ancient Greek World", 21–62</ref><ref name="Sykoutris">I. Sykoutris, ''Symposium (Introduction and Comments)'', 152–153</ref> According to [[Charles H. Kahn]], Professor of Philosophy at the [[University of Pennsylvania]], Diotima is in many respects Plato's response to Aeschines' Aspasia.<ref name="Kahn26">C.H. Kahn, ''Plato and the Socratic Dialogue'', 26–27</ref> |

|||

{{quote box |

|||

|align=left |

|||

|width=40% |

|||

|border=1px |

|||

|quote= "Now, since it is thought that he proceeded thus against the Samians to gratify Aspasia, this may be a fitting place to raise the query what great art or power this woman had, that she managed as she pleased the foremost men of the state, and afforded the philosophers occasion to discuss her in exalted terms and at great length." |

|||

|source= Plutarch, ''Pericles'', [http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0007.tlg012.perseus-eng1:24.1 XXIV] |

|||

}} |

|||

In ''[[Menexenus (dialogue)|Menexenus]]'', Plato satirizes Aspasia's relationship with Pericles,<ref name="Allen29-30">P. Allen, ''The Concept of Woman'', 29–30</ref> and quotes Socrates as claiming ironically that she was a trainer of many orators and that since Pericles was educated by Aspasia, he would be superior in [[rhetoric]] to someone educated by [[Antiphon (person)|Antiphon]].<ref name="Menexenus236">Plato, ''Menexenus'', [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0059.tlg028.perseus-eng1:236a 236a]</ref> He also attributes authorship of the Funeral Oration to Aspasia and attacks his contemporaries' veneration of Pericles.<ref name="Mon182-186">S. Monoson, ''Plato's Democratic Entanglements'', 182–186</ref> Kahn maintains that Plato has taken from Aeschines the motif of Aspasia as teacher of rhetoric for Pericles and Socrates.<ref name="Kahn26" /> Plato's Aspasia and Aristophanes' [[Lysistrata]] are two apparent exceptions to the rule of women's incapacity as orators, although these fictional characters tell us nothing about the status of women in Athens.<ref name="Rothwell22">K. Rothwell, ''Politics & Persuasion in Aristophanes' Ecclesiazusae'', 22</ref> As Martha L. Rose, Professor of History at [[Truman State University]], explains, "only in comedy do dogs litigate, birds govern, or women declaim".<ref>M.L. Rose, ''The Staff of Oedipus'', 62</ref> |

|||

Xenophon mentions Aspasia twice in his Socratic writings: in ''[[Memorabilia (Xenophon)|Memorabilia]]'' and in ''[[Oeconomicus]]''. In both cases her advice is recommended to Critobulus by Socrates. In ''Memorabilia'' Socrates quotes Aspasia as saying that the matchmaker should report truthfully on the good characteristics of the man.<ref name="X36">Xenophon, ''Memorabilia'', 2, 6.[https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0208&layout=&loc=2.6.1 36]</ref> In ''Oeconomicus'' Socrates defers to Aspasia, as more knowledgeable about household management and the economic partnership between husband and wife.<ref name="X14">Xenophon, ''Oeconomicus'', 3.14</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Illus0362.jpg|thumb|Pericles and Aspasia admiring the gigantic statue of Athena in [[Phidias]]' studio, portrayed in a painting by Hector Leroux (1682–1740)]] |

|||

Aeschines Socraticus and Antisthenes each named a [[Socratic dialogue]] after Aspasia (although neither survives except in fragments). Our major sources for Aeschines Socraticus' ''Aspasia'' are Athenaeus, Plutarch, and [[Cicero]], all witting centuries later. In the dialogue, Socrates recommends that Callias send his son Hipponicus to Aspasia for instructions. When Callias recoils at the notion of a woman teaching him, Socrates notes that Aspasia had favorably influenced Pericles and, after his death, Lysicles. In a section of the dialogue, preserved in [[Latin]] by Cicero, Aspasia figures as a "female Socrates", counseling first Xenophon's wife and then Xenophon (the Xenophon in question is not the famous historian) about acquiring virtue through self-knowledge.<ref name="Kahn26" /><ref name="Cic51-53">Cicero, ''De Inventione'', I, 51–53</ref> Aeschines presents Aspasia as a teacher and inspirer of excellence, connecting these virtues with her status as hetaira.<ref name="Vander96-98">C.H. Kahn, ''Aeschines on Socratic Eros'', 96–99</ref> According to Kahn, every single episode in Aeschines' Aspasia is not only fictitious but incredible.<ref name="Kahn34">C.H. Kahn, ''Plato and the Socratic Dialogue'', 34</ref> |

|||

Of Antisthenes' ''Aspasia'' only two or three quotations are extant.<ref name="Nails58-59" /> This dialogue contains much slander, but also anecdotes pertaining to Pericles' biography.<ref name="B104">Bolansée-Schepens-Theys-Engels, ''Biographie'', 104</ref> Antisthenes appears to have attacked not only Aspasia, but the entire family of Pericles, including his sons. The philosopher believes that the great statesman chose the life of pleasure over virtue.<ref name="Kahn9">C.H. Kahn, ''Plato and the Socratic Dialogue'', 9</ref> Thus, Aspasia is presented as the personification of the life of sexual indulgence.<ref name="Vander96-98" /> |

|||

==Fame and assessments== |

|||

Aspasia's name is closely connected with Pericles' glory and fame.<ref>K. Paparrigopoulos, Ab, 220</ref> Plutarch accepts her as a significant figure both politically and intellectually and expresses his admiration for a woman who "managed as she pleased the foremost men of the state, and afforded the philosophers occasion to discuss her in exalted terms and at great length".<ref name="Pl24" /> The biographer says that Aspasia became so renowned that even [[Cyrus the Younger]], who went to war with the King [[Artaxerxes II of Persia]], gave her name to one of his concubines, who before was called Milto. After Cyrus had fallen in battle, this woman was carried captive to the king and acquired a great influence with him.<ref name="Pl24" /> [[Lucian]] calls Aspasia a "model of wisdom", "the admired of the admirable Olympian" and lauds "her political knowledge and insight, her shrewdness and penetration".<ref name="Lucian">Lucian, ''A Portrait Study'', XVII</ref> A [[Syriac language|Syriac]] text, according to which Aspasia composed a speech and instructed a man to read it for her in the courts, confirms Aspasia's rhetorical fame.<ref name="McClure20">L. McClure, ''Spoken like a Woman'', 20</ref> Aspasia is said by the ''[[Suda]]'', a tenth-century [[Byzantine Empire|Byzantine]] encyclopedia, to have been "clever with regards to words", a [[sophism|sophist]], and to have taught rhetoric.<ref name="Suda">Suda, article [http://www.stoa.org/sol-bin/search.pl?login=guest&enlogin=guest&db=REAL&field=adlerhw_gr&searchstr=alpha,4202 Aspasia] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924122324/http://www.stoa.org/sol-bin/search.pl?login=guest&enlogin=guest&db=REAL&field=adlerhw_gr&searchstr=alpha,4202 |date=2015-09-24 }}</ref> |

|||

{{quote box |

|||

|align=left |

|||

|width=40% |

|||

|quote= "Next I have to depict Wisdom; and here I shall have occasion for many models, most of them ancient; one comes, like the lady herself, from Ionia. The artists shall be Aeschines and Socrates his master, most realistic of painters, for their heart was in their work. We could choose no better model of wisdom than Milesian Aspasia, the admired of the admirable 'Olympian'; her political knowledge and insight, her shrewdness and penetration, shall all be transferred to our canvas in their perfect measure. Aspasia, however, is only preserved to us in miniature: our proportions must be those of a colossus." |

|||

|source=[[Lucian]], ''A Portrait Study'', [http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/luc/wl3/wl303.htm XVII] |

|||

}} |

|||

On the basis of such assessments, researchers such as Cheryl Glenn, professor at the [[Pennsylvania State University]], argue that Aspasia seems to have been the only woman in classical Greece to have distinguished herself in the public sphere and must have influenced Pericles in the composition of his speeches.<ref name="GlennRemapping">C. Glenn, ''Remapping Rhetorical Territory '', 180–199</ref> Some scholars believe that Aspasia opened an academy for young women of good families or even invented the [[Socratic method]].<ref name="GlennLocating">C. Glenn, ''Locating Aspasia on the Rhetorical Map'', 23</ref><ref name="Jarratt">Jarratt-Onq, ''Aspasia: Rhetoric, Gender, and Colonial Ideology'', 9–24</ref> However, Robert W. Wallace, Professor of classics at [[Northwestern University]], underscores that "we cannot accept as historical the joke that Aspasia taught Pericles how to speak and hence was a master rhetorician or philosopher". According to Wallace, the intellectual role Aspasia was given by Plato may have derived from [[Ancient Greek comedy|comedy]].<ref name="Wallace">R.W. Wallace, [http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/bmcr/1996/96.04.07.html Review of Henry's book]</ref> Roger Just, a [[Classics|classicist]] and Professor of [[social anthropology]] at the [[University of Kent]], believes that Aspasia was an exceptional figure, but her example alone is enough to underline the fact that any woman who was to become the intellectual and social equal of a man would have to be a hetaera.<ref name="Just144" /> According to Sr. [[Prudence Allen]], a philosopher and seminary professor, Aspasia moved the potential of women to become philosophers one step forward from the poetic inspirations of [[Sappho]].<ref name="Allen29-30" /> |

|||

==Accuracy of historical sources== |

|||

The main problem remains, as [[Jona Lendering]] points out,<ref>[https://www.livius.org/articles/person/aspasia/ Aspasia of Miletus] at livius.org</ref> that most of the things we know about Aspasia are based on mere hypothesis. [[Thucydides]] does not mention her; our only sources are the untrustworthy representations and speculations recorded by men in literature and philosophy, who did not care at all about Aspasia as a historical character.<ref name="Wallace" /><ref name="Rothwell22" /> Therefore, in the figure of Aspasia, we get a range of contradictory portrayals; she is either a good wife like [[Theano]] or some combination of courtesan and prostitute like [[Thargelia (person)|Thargelia]].<ref name="Taylor187">J.E. Taylor, ''Jewish Women Philosophers of First-Century Alexandria'', 187</ref> For this reason, modern scholars are generally skeptical of claims the ancient sources make about her life.<ref name="Wallace" /> |

|||

According to Wallace, "for us Aspasia herself possesses and can possess almost no historical reality".<ref name="Wallace" /> Hence, Madeleine M. Henry, Professor of Classics at [[Iowa State University]], maintains that "biographical anecdotes that arose in antiquity about Aspasia are wildly colorful, almost completely unverifiable, and still alive and well in the twentieth century". She finally concludes that "it is possible to map only the barest possibilities for [Aspasia's] life".<ref name="Henry3">M. Henry, ''Prisoner of History'', 3, 10, 127–128</ref> According to Charles W. Fornara and Loren J. Samons II, Professors of Classics and history, "it may well be, for all we know, that the real Aspasia was more than a match for her fictional counterpart".<ref name="Fornara" /> |

|||

===Modern literature=== |

|||

[[Image:Aspasia painting.jpg|thumb|Self-portrait of [[Marie Bouliard]], as Aspasia, 1794]] |

|||

Aspasia appears in several significant works of modern literature. Her romantic attachment with Pericles has inspired some of the most famous [[novelist]]s and [[poetry|poets]] of the last centuries. In particular the [[romanticism|romanticists]] of the 19th century and the [[historical novel]]ists of the 20th century found in their story an inexhaustible source of inspiration. In 1835 [[Lydia Maria Child]], an American [[Abolitionism in the United States|abolitionist]], [[novelist]], and [[journalist]], published ''Philothea'', a classical romance set in the days of Pericles and Aspasia. This book is regarded as "the most elaborate and successful of the author's productions", in which the female characters, including Aspasia, "are portrayed with great beauty and delicacy."<ref name="EA198">Duyckinck & Duyckinck, ''Cyclopaedia of American Literature'', [https://archive.org/stream/cyclopaediaofame02duyc#page/388 388]</ref> |

|||

[[Letitia Elizabeth Landon]]'s poem {{ws|[[s:Landon in The New Monthly 1836/Banquet Aspasia and Pericles|The Banquet of Aspasia and Pericles]]}} (1836) is one of her series, Subjects for Pictures. |

|||

In 1836, [[Walter Savage Landor]], an English [[writer]] and [[poet]], published ''Pericles and Aspasia'', one of his most famous books. ''Pericles and Aspasia'' is a rendering of classical Athens through a series of imaginary letters, which contain numerous poems. The letters are frequently unfaithful to history but attempt to capture the spirit of the [[Age of Pericles]].<ref name="Mac195">R. MacDonald Alden, ''Readings in English Prose'', 195</ref> [[Robert Hamerling]] is another novelist and poet who was inspired by Aspasia's personality. In 1876 he published his novel ''Aspasia'', a book about the manners and morals of the Age of Pericles and a work of cultural and historical interest. [[Giacomo Leopardi]], an Italian poet influenced by the movement of romanticism, published a group of five poems known as the ''circle of Aspasia''. These Leopardi poems were inspired by his painful experience of desperate and unrequited love for a woman named Fanny Targioni Tozzetti. Leopardi called this person Aspasia, after the companion of Pericles.<ref name="Brose271">M. Brose, ''A Companion to European Romanticism'', 271</ref> |

|||

In 1918, novelist and [[playwright]] [[George Cram Cook]] produced his first full-length play, ''The Athenian Women'' (an adaption of ''[[Lysistrata]]''<ref>{{citation |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ooexAo1dwFIC&q=George+Cram+Cook+athenian+women&pg=PA321 |title=Women Writers of the Provincetown Players: A Collection of Short Works |last=Judith E. Barlow |page=321|isbn=9781438427904 |date=2009-10-21 }}</ref>), which portrays Aspasia leading a strike for peace.<ref name="Greasley120">D.D. Anderson, ''The Literature of the Midwest'', 120</ref> Cook combined an anti-war theme with a Greek setting.<ref>M Noe, [http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/spec-coll/Bai/noe.htm "Susan Glaspell's Analysis of the Midwestern Character"] Books at Iowa 27 November 1977</ref> American writer [[Gertrude Atherton]] in ''The Immortal Marriage'' (1927) treats the story of Pericles and Aspasia and illustrates the period of the Samian War, the Peloponnesian War and the Plague of Athens. [[Taylor Caldwell]]'s ''Glory and the Lightning'' (1974) is another novel that portrays the historical relationship of Aspasia and Pericles.<ref>L.A. Tritle, The Peloponnesian War, 199</ref> |

|||

==In contemporary art== |

|||

The 1979 installation artwork ''[[The Dinner Party]]'' by feminist [[Judy Chicago]] has a place setting for Aspasia among the 39 figured.<ref>[https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/place_settings Place Settings]. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved on 2015-08-06.</ref> |

|||

Aspasia appears in ''[[Assassin's Creed Odyssey]]'' as the partner of the Athenian statesman Pericles and antagonist as leader of the Cult of Kosmos. |

|||

Aspasia is the protagonist in [[Taylor Caldwell]]'s novel ''Glory and the Lightning'', 1974, Doubleday & Company. |

|||

==See also== |

|||

*[[Ancient philosophy]] |

|||

*[[List of speakers in Plato's dialogues]] |

|||

*[[Prostitution in Ancient Greece]] |

|||

*[[Timeline of Ancient Greece]] |

|||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

| Line 124: | Line 62: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{ |

{{reflist|25em}} |

||

== |

==Bibliography== |

||

* {{cite book|last=Azoulay|first=Vincent|title=Pericles of Athens|translator-last=Lloyd|translator-first=Janet|year=2014|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-0-691-15459-6|orig-date=Published in French 2010}} |

|||

{{refbegin}} |

|||

; Primary sources (Greeks and Romans) |

|||

* Aristophanes, ''Acharnians''. [https://archive.org/stream/aristophaneswith01arisuoft#page/n27/mode/1up original text in Internet Archive] |

|||

* Athenaeus of Naucratis, ''[[Deipnosophistae]]''. Translated by Yonge, C.D. [http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/Literature.DeipnoSub text at University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center] |

|||

* Cicero, ''De Inventione'', I. [http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/cicero/inventione1.shtml original text] Latin Library. |

|||

* [[Diodorus Siculus]], ''Library'', XII. [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0060.tlg001.perseus-eng1:12.40.6 original text at Perseus program]. |

|||

* Lucian, [http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/luc/wl3/wl303.htm ''A Portrait-study'']. from ''The Works of Lucian of Samosata'' translated by H.W. Fowler and F.G. Fowler Oxford: The Clarendon Press [1905] at sacred-texts.com |

|||

* Plato, ''Menexenus''. ''Plato in Twelve Volumes'', Vol. 9 translated by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925 [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0059.tlg028.perseus-eng1:236a original text at Perseus program]. |

|||

* Plutarch, ''Pericles''. [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0007.tlg012.perseus-eng1 original text at Perseus program]. |

|||

* Thucydides, ''The Peloponnesian War'', I and III. London, J.M. Dent; New York, E.P. Dutton. 1910. In [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0200&query=book%3D%233 Perseus program] |

|||

* Xenophon, ''Memorabilia''. ''Xenophon in Seven Volumes'', 4. E.C. Marchant. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann, Ltd., London. 1923 [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0208 at Perseus program] |

|||

* Xenophon, ''Oeconomicus''. Translator: [[Henry Graham Dakyns|H. G. Dakyns]] "The Works of Xenophon," [https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1173 at Gutenberg project, Last Updated: January 15, 2013]. |

|||

; Secondary sources |

|||

* {{cite encyclopedia |editor-last=Adams |editor-first=Henry Gardiner |editor-link=Henry Gardiner Adams |encyclopedia=A Cyclopaedia of Female Biography |year=1857 |publisher=Groombridge and Sons |location=London |title=Aspasia |url= https://archive.org/details/acyclopaediafem01adamgoog}} |

|||

* {{cite book |first=Raymond MacDonald |last= Alden |title=Readings in English Prose of the Nineteenth Century |publisher=Kessinger Publishing |year=2005 |orig-year=1917 |isbn=978-0-8229-5553-5 |chapter=Walter Savage Landor}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Allen |first=Prudence|title=The Concept of Woman: The Aristotelian Revolution, 750 B.C. – A.D. 1250 |year=1997 |publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing |isbn=978-0-8028-4270-1 |chapter=The Pluralists: Aspasia }} |

|||

* {{cite book |first=D.D. |last = Anderson |title=Dictionary of Midwestern Literature: Volume One: The Authors by Philip A Greasley |publisher=Indiana University Press |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-253-33609-5 |chapter=The Origins and Development of the Literature of the Midwest }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last=Arkins |first=Brian |title=Sexuality in Fifth-Century Athens |journal=Classics Ireland |volume=1|year=1994 |pages=18–34 |doi=10.2307/25528261 |jstor=25528261 |access-date=2006-08-29 |url = http://www.ucd.ie/cai/classics-ireland/1994/Arkins94.html }} |

|||

* {{cite encyclopedia |title=Aspasia |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |year=2002 }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last=Bicknell|first=Peter J. |title=Axiochus Alkibiadou, Aspasia and Aspasios |journal=L'Antiquité Classique |year=1982|volume=51|issue=3|pages=240–250|doi=10.3406/antiq.1982.2070 |url=http://www.persee.fr/docAsPDF/antiq_0770-2817_1982_num_51_1_2070.pdf}} |

* {{cite journal |last=Bicknell|first=Peter J. |title=Axiochus Alkibiadou, Aspasia and Aspasios |journal=L'Antiquité Classique |year=1982|volume=51|issue=3|pages=240–250|doi=10.3406/antiq.1982.2070 |url=http://www.persee.fr/docAsPDF/antiq_0770-2817_1982_num_51_1_2070.pdf}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Blundell|first=Sue|year=1995|title=Women in Ancient Greece|publisher=Harvard University Press|isbn=978-0-674-95473-1|url=https://archive.org/details/womeninancientgr00blun/mode/2up}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Bolansée |first1=Schepens|last2=Theys|first2=Engels |title=Die Fragmente Der Griechischen Historiker: A. Biography |year=1989 |publisher=Brill Academic Publishers |isbn=978-90-04-11094-6 |chapter=Antisthenes of Athens }} |

|||

* {{cite book |first1=Charles W. |last1=Fornara |first2=Loren J. |last2=Samons |title=Athens from Cleisthenes to Pericles |publisher= University of California Press |location=Berkeley, CA |year=1991 |url = http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2p30058m/ }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Brose |first= Margaret |title = A Companion to European Romanticism |editor-first=Michael |editor-last=Ferber |publisher=Blackwell Publishing |year=2005 |isbn=978-1-4051-1039-6 |chapter=Ugo Foscolo and Giacomo Leopardi: Italy's Classical Romantics }} |

|||

* {{cite journal|last1=Geraths|last2=Kennerly|first1=Cory|first2=Michele|title=Painted Lady: Aspasia in Nineteenth-Century European Art|journal=Rhetoric Review|volume=35|issue=3|year=2016|doi=10.1080/07350198.2016.1178688}} |

|||

* {{cite encyclopedia |last2=Duyckinck |first2=G.L. |last1=Duyckinck |first1=E.A. |title = Lydia Maria Child |encyclopedia=Cyclopaedia of American Literature|volume=II|year=1856|publisher=C. Scribner}} |

|||

* {{cite book |first1=Loren J. |last1=Samons II |last2 = Fornara |first2=Charles W. |title=Athens from Cleisthenes to Pericles |publisher= University of California Press |location=Berkeley, CA |year=1991 |url = http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2p30058m/ }} |

|||

* {{cite book |first=Cheryl |last = Glenn |title=Listening to Their Voices |publisher=Univ of South Carolina Press |year=1997 |isbn=978-1-57003-172-4 |chapter=Locating Aspasia on the Rhetorical Map }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last=Glenn |first=Cheryl |title=Sex, Lies, and Manuscript: Refiguring Aspasia in the History of Rhetoric |journal=Composition and Communication |year=1994 |volume=45 |issue=4 |pages=180–199 |doi=10.2307/359005 |jstor=359005 }} |

|||

* {{cite book |first=Arnold W. |last = Gomme |author-link = Arnold Wycombe Gomme |title=Essays in Greek History & Literature |publisher=Ayer Publishing |year=1977 |isbn=978-0-8369-0481-9 |chapter=The Position of Women in Athens in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BC }} |

|||

* {{cite book |editor1-last=Hammond |editor1-first=N.G.L. |editor2-last=Scullard |editor2-first=H.H. |title=The Oxford Classical Dictionary |year=1970 |edition=2nd |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=London |isbn=978-0198691174 |url=https://archive.org/details/oxfordclassicald00hamm }} |

|||

* {{cite book |first=Madeleine M. |last=Henry |title=Prisoner of History. Aspasia of Miletus and her Biographical Tradition |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1995 |isbn=978-0-19-508712-3 }} |

* {{cite book |first=Madeleine M. |last=Henry |title=Prisoner of History. Aspasia of Miletus and her Biographical Tradition |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1995 |isbn=978-0-19-508712-3 }} |

||

* {{cite |

* {{cite journal|last=Ianetta|first=Melissa|title='She Must Be a Rare One': Aspasia, 'Corinne', and the Improvisatrice Tradition|journal=PMLA|year=2008|volume=123|issue=1}} |

||

* {{cite |

* {{cite thesis|last=Jordan|first=Nicole|title="A Very Amusing Bit of Blasphemy": Honoré Daumier's Histoire Ancienne|publisher=University of Alabama|year=2012}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book|last=Kapparis|first=Konstantinos|title=Prostitution in the Ancient Greek World|publisher=De Gruyter|location=Berlin|year=2018|isbn=978-3-11-055795-4}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book|last=Kennedy|first=Rebecca Futo|authorlink=Rebecca Futo Kennedy|title=Immigrant Women in Athens: Gender, Ethnicity and Citizenship in the Classical City|year=2014|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-0-415-73786-9}} |

||

* {{cite journal|last=Loraux|first=Nicole|author-link=Nicole Loraux|title=Aspasia, Foreigner, Intellectual|translator-last=Ling|translator-first=Alex|journal=Journal of Continental Philosophy|year=2021|volume=2|issue=1|doi=10.5840/jcp2021102823|orig-date=Published in French 2003}} |

|||

* {{cite book |first=Roger |last=Just |title=Women in Athenian Law and Life |publisher=Routledge (UK) |year=1991 |isbn=978-0-415-05841-4 |chapter=Personal Relationships }} |

|||

* {{cite book |first=Nicole |last=Loraux |title = La Grèce au Féminin |language = fr |publisher= Belles Lettres |year=2003 |isbn=978-2-251-38048-3 |chapter=Aspasie, l'étrangère, l'intellectuelle }} |

|||

* Mazzon, Daniela, ''Aspasia maestra e amante di Pericle'', EdizioniAnordest, 2011 (in Italian) {{ISBN|9788896742280}} |

|||

* Mazzon, Daniela, ''Desiderata Aspasia. Rapsodia mediterranea'', one-act drama, 2012 (in Italian) |

|||

* {{cite book |first=Laura |last=McClure |title=Spoken Like a Woman: Speech and Gender in Athenian Drama |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=1999 |isbn=978-0-691-01730-3 |chapter=The City of Words: Speech in the Athenian Polis }} |

|||

* {{cite book |first=James F. |last=McGlew |title=Citizens on Stage: Comedy and Political Culture in the Athenian Democracy |publisher=University of Michigan Press |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-472-11285-2 |chapter=Exposing Hypocrisie: Pericles and Cratinus' Dionysalexandros }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Monoson|first=Sara |title=Plato's Democratic Entanglements |publisher=Hackett Publishing |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-691-04366-1 |chapter=Plato's Opposition to the Veneration of Pericles }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Nails|first=Debra |author-link=Debra Nails |title=The People of Plato: A Prosopography of Plato and Other Socratics |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-87220-564-2 }} |

* {{cite book |last=Nails|first=Debra |author-link=Debra Nails |title=The People of Plato: A Prosopography of Plato and Other Socratics |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-87220-564-2 }} |

||

* {{cite book | |

* {{cite book |first= Anthony J. |last=Podlecki |title=Perikles and His Circle |publisher=Routledge |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-415-06794-2 }} |

||

* {{cite journal|last=Pomeroy|first=Sarah B.|author-link=Sarah Pomeroy|year=1996|title=Review: Madeleine M. Henry, ''Prisoner of History''|journal=The American Journal of Philology|volume=117|issue=4|jstor=1561953}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Ostwald|first=M. |title=The Cambridge Ancient History |editor-last1=Lewis|editor-first1=David M.|editor-last2=Boardman|editor-first2=John|editor-last3=Davies|editor-first3=J.K.|editor-last4=Ostwald |editor-first4=M. |volume=V |year=1992 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-23347-7 |chapter=Athens as a Cultural Center }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Taylor |first=A.E. |title=Plato: The Man and His Work |publisher=Methuen |year=1955 |isbn=978-0-486-41605-2 |url=https://archive.org/details/platothemanandhi032950mbp/page/n7/mode/2up|edition=6th|orig-date=1st edition 1926}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1 = Paparrigopoulos |first1=Konstantinos |last2 = Karolidis |first2 = Pavlos |year=1925 |title=History of the Hellenic Nation (Volume Ab) |publisher=Eleftheroudakis |language=el }} |

|||

* {{cite journal|last=Wallace|first=Robert|year=1996|title=Review: Madeleine M. Henry, ''Prisoner of History''|journal=Bryn Mawr Classical Review|url=https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/1996/1996.04.07}} |

|||

* {{cite book |first= A.J. |last=Podlecki |title=Perikles and His Circle |publisher=Routledge (UK) |year=1997 |isbn=978-0-415-06794-2 }} |

|||

* {{cite book |title=The Greek World |last=Powell |first=Anton |publisher=Routledge (UK) |year=1995 |isbn=978-0-415-06031-8 |chapter=Athens' Pretty Face: Anti-feminine Rhetoric and Fifth-century Controversy over the Parthenon }} |

|||

* {{cite book |title=The Staff of Oedipus |last=Rose|first=Martha L. |publisher=University of Michigan Press |year=2003 |isbn=978-0-472-11339-2 |chapter=Demosthenes' Stutter: Overcoming Impairment }} |

|||

* {{cite book |title=Politics and Persuasion in Aristophanes' Ecclesiazusae |last=Rothwell |first=Kenneth Sprague |publisher=Brill Academic Publishers |year=1990 |isbn=978-90-04-09185-6 |chapter=Critical Problems in the Ecclesiazusae }} |

|||

* {{cite book |title = A History of Greece |last=Smith |first=William |publisher=R.B. Collins |year=1855 |chapter=Death and Character of Pericles }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Southall |first=Aidan |author-link=Aidan Southall |title=The City in Time and Space |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=1999 |isbn=978-0-521-78432-0 |chapter=Greece and Rome }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Stadter |first=Philip A. |title=A Commentary on Plutarch's Pericles |publisher=University of North Carolina Press |year=1989 |isbn=978-0-8078-1861-9 |url=https://archive.org/details/commentaryonplut00stad }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Sykoutris |first=Ioannis |title=Symposium (Introduction and Comments) |language = el |publisher=Estia |year=1934 }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Taylor |first = A.E. |title = Plato: The Man and His Work |publisher= Courier Dover Publications |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-486-41605-2 |chapter=Minor Socratic Dialogues: Hippias Major, Hippias Minor, Ion, Menexenus }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Taylor |first=Joan E. |title=Jewish Women Philosophers of First-Century Alexandria |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2004 |isbn=978-0-19-925961-8 |chapter=Greece and Rome }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Tritle |first=Lawrence A. |title=The Peloponnesian War |publisher=Greenwood Press |year=2004|isbn=978-0-313-32499-4 |chapter=Annotated Bibliography }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last=Wider |first=Kathleen |title=Women philosophers in the Ancient Greek World: Donning the Mantle |journal=[[Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy|Hypatia]] |year=1986|volume=1|issue=1|pages=21–62 |doi=10.1111/j.1527-2001.1986.tb00521.x }} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

{{Refbegin}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Atherton|first=Gertrude|title=The Immortal Marriage|publisher=Kessinger Publishing|year=2004|isbn=978-1-4179-1559-0}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last= Becq de Fouquières|first=Louis|title=Aspasie de Milet (in French)|url= https://archive.org/details/aspaisedemilete00fouqgoog|publisher=Didier|year=1872}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last= Cozzi|first=Cecilia|title=Aspasia, storia di una donna (in Italian)|publisher=David and Matthaus|year=2014|isbn=978-88-98899-01-2}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Dover|first=K.J.|title=Greeks and Their Legacy|year=1988|publisher=Blackwell|location=New York|chapter=The Freedom of the Intellectual in Greek Society}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last= Hamerling|first=Louis|title=Aspasia: a Romance of Art and Love in Ancient Hellas|publisher=Geo. Gottsberger Peck|year=1893}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Savage Landor|first=Walter|title=Pericles And Aspasia|publisher=Kessinger Publishing|year=2004|isbn=978-0-7661-8958-4}} |

|||

{{Refend}} |

|||

== External links == |

|||

{{Commons}} |

|||

; Biographical |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

| title = Aspasia of Athens |

|||

| work = Brainard, Jennifer |

|||

| url = http://www.feministezine.com/feminist/philosophy/Aspasia.html |

|||

| access-date = August 14, 2007 |

|||

| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070928041042/http://www.feministezine.com/feminist/philosophy/Aspasia.html | archive-date = 28 September 2007 | url-status= live }} |

|||

* {{cite EB1911|wstitle=Aspasia}} |

|||

* {{cite encyclopedia |

|||

| title = Aspasia |

|||

| encyclopedia = Encyclopædia Romana |

|||

| url = http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/greece/hetairai/aspasia.html |

|||

| access-date = September 10, 2006 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

| title = ''Aspasia of Miletus – Prisoner of History'', by Madeleine Henry |

|||

| work=About.com Education, Book Reviews |

|||

| last = Gill |

|||

| first = N.S. |

|||

| url = http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/philosophers/a/Aspasia.htm |

|||

| access-date = September 10, 2006 |

|||

| archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20060820145301/http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/philosophers/a/Aspasia.htm |archive-date= 20 August 2006 |url-status= live}} |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

| title = Aspasia of Miletus |

|||

| author = Lendering, Jona |

|||

| url = https://www.livius.org/articles/person/aspasia/ |

|||

| access-date = September 10, 2006 |

|||

| archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20060831135142/https://www.livius.org/as-at/aspasia/aspasia.html |archive-date= 31 August 2006 |url-status = live }} |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

| title = Aspasia of Miletus |

|||

| author = O'Grady, Patricia | author-link = Patricia O'Grady |

|||

| url = http://home.vicnet.net.au/~hwaa/artemis4.html |

|||

| access-date = September 10, 2006 |

|||

| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20061201015330/http://home.vicnet.net.au/~hwaa/artemis4.html |

|||

| archive-date=December 1, 2006 |

|||

| url-status = dead |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

| title = Aspasia, from PBS's "The Greeks" |

|||

| work = The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization on PBS |

|||

| url = https://www.pbs.org/empires/thegreeks/htmlver/characters/f_aspasia.html |

|||

| access-date = November 1, 2006 |

|||

| archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20060929212535/http://www.pbs.org/empires/thegreeks/htmlver/characters/f_aspasia.html | archive-date= 29 September 2006 | url-status= live}} |

|||

; Miscellaneous |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

| title = Aspasia in Greek Comedy |

|||

| work = About Education, Book Reviews |

|||

| last = Gill |

|||