Harry Potter

| File:Harry potter stamps.jpg A set of stamps commissioned by Royal Mail, featuring the British children's covers of the seven books.[1] | |

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows | |

| Author | J. K. Rowling |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy, thriller, bildungsroman |

| Publisher | Bloomsbury Publishing (UK) Scholastic Publishing (USA) |

| Published | June 26, 1997–July 21, 2007 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover and paperback) Audiobook |

Harry Potter is a series of seven fantasy novels written by British author J. K. Rowling. The books chronicle the adventures of the eponymous adolescent wizard Harry Potter, together with Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger, his best friends from the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. The central story arc concerns Harry's struggle against the evil wizard Lord Voldemort, who killed Harry's parents in his quest to conquer the Wizarding world, after which he seeks to subjugate the Muggle (non-magical population) world to his rule. The stories have inspired films, video games and other themed merchandise.

Since the release of the first novel Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone in 1997, which was retitled Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone in the United States, the books have gained immense popularity, critical acclaim and commercial success worldwide.[2] As of June 2008, the book series has sold more than 400 million copies,[3] has been translated into 67 languages[4] and the last four books have consecutively set records as the fastest-selling books in history.[5][6][7]The seventh and last book in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, was released on July 21, 2007.[8] Publishers announced a record-breaking 12 million copies for the first print run in the United States alone.[9]

The success of the novels has made Rowling the highest-earning novelist in history.[10] English language versions of the books are published by Bloomsbury in the United Kingdom, Scholastic Press in the United States, Allen & Unwin in Australia, and Raincoast Books in Canada. Thus far, the first five books have been made into a series of motion pictures by Warner Bros. The sixth, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, is scheduled for release on July 17, 2009.[11] The series also originated much tie-in merchandise, making the Harry Potter brand worth £7 billion ($15 billion).[12]

Series overview

Books

Harry Potter, the protagonist of the series, is an orphan, born into the Wizarding world, a land of magic and mythical creatures. However, when still a baby he witnesses his parents' murder by Lord Voldemort, a fascist Dark wizard with an ideology of racial purity. For reasons not immediately revealed, Voldemort's attempt to kill Harry rebounds onto him, seemingly killing him. Harry survives, but is left with a lightning-shaped mark on his forehead as a memento of the attack. As a result, Harry becomes a living legend in the wizard world. However, at the orders of his patron, the wizard Albus Dumbledore, Harry is placed in the home of his Muggle (non-wizard) relatives, and raised in our realm, completely ignorant of his true heritage. The series proper begins on Harry's eleventh birthday, when the half-giant Rubeus Hagrid reveals his history and introduces him to the wizard world.

Each book chronicles one year in Harry's life, which is mostly spent at Hogwarts, a boarding school for young wizards. There, he learns to use magic and brew potions. Eventually Harry learns that Lord Voldemort is still alive and plotting his return to power. Harry also learns to overcome many magical, social, and emotional hurdles as he struggles through his adolescence. He must also confront the corrupt and oblivious government of the Wizarding world, the Ministry of Magic.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone

The first book of the series highlights Harry's first year at Hogwarts and introduces most of the main characters, as well as many locations used throughout the rest of the series. Harry gains his two closest friends; Ron Weasley, a kind hearted member of an ancient wizarding family, and Hermione Granger, an obsessively bookish witch of non-magical parentage. The plot includes the first steps Harry takes into the magical world, and concludes with his second confrontation with Voldemort, who in his quest for immortality, yearns to gain the power of the Philosopher's Stone.

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

In Harry's second year at Hogwarts, Voldemort attempts to reincarnate himself through the memories he stored within a diary. Also in this book, Harry realises his ability to speak Parseltongue, the rare language of snakes that is often equated with the dark arts. The novel delves into the history of Hogwarts and a legend revolving around the "Chamber of Secrets", the underground lair of an ancient evil. The book has an important thematic connection with the sixth book, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince.

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban tells of Harry's third year of magical education, during which the characters of Remus Lupin, a Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher with a dark secret and close ties to Harry's family, and Sirius Black, a convicted murderer believed to have targeted Harry, are introduced. The novel also introduces the dementors, dark creatures with the power to devour a human soul that the Ministry mistakenly believes it can control. It is the only book in the series which does not feature Voldemort.

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

In Harry's fourth year, he unwillingly participates in the Triwizard Tournament, a dangerous magical contest between Hogwarts and two other European wizard schools, Beauxbatons and Durmstrang. The plot centres on Harry's attempt to unravel the mystery of who has forced him to compete in the tournament, and why. The point at which the mystery is unravelled also marks the series' shift from foreboding and uncertainty into open conflict. The novel ends with the resurgence of Voldemort and the death of a student.

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix

In the fifth book, Harry Potter must confront the newly-resurfaced Voldemort, as well as the rest of magical world who refuse to believe that this is true, including the Ministry of Magic. The Ministry appoints Dolores Umbridge as the new director of Hogwarts, and she transforms the school into a quasi-dictatorial regime. Luna Lovegood, an airy young witch with a tendency to believe in oddball conspiracy theories, is introduced. Moreover, it reveals an important prophecy concerning Harry and Voldemort, and finally, recounts the murder of Sirius Black.

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince

In this sixth book, Harry stumbles upon an old potions textbook filled with annotations and recommendations signed by a mysterious writer with the pseudonym of the Half-Blood Prince. He also participates in private tutoring sessions with Albus Dumbledore, who shows him various memories concerning the early life of Voldemort. These sessions reveal that Voldemort's soul is splintered into a series of horcruxes; evil enchanted items hidden in various locations. At the end of the book, Professor Severus Snape, whose loyalty was questioned throughout the series, murders Dumbledore and flees the school.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

This book starts directly after the death of Dumbledore, after which Voldemort completes his ascension to power and acquires control of the Ministry of Magic. Harry and his friends decide not to attend their final year at Hogwarts in order to search for the remaining Horcruxes. The book also reveals details about Dumbledore's past, as well as Snape's true intentions. The battle of Hogwarts inevitably occurs, featuring members of the Order of the Phoenix, students and teachers from Hogwarts, Voldemort and his Death Eaters, and various magical creatures. After the deaths of many people and creatures, Voldemort is slain by Harry, and the Wizarding world returns to how it was before Voldemort corrupted the community.[13]

Supplementary works

J. K. Rowling has written additional books related to the Harry Potter universe, all of which have been produced for various charities.[14][15] Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them and Quidditch Through the Ages (2001) were written as part of a fundraiser for the charity Comic Relief. In 2007, Rowling composed seven handwritten copies of The Tales of Beedle the Bard, a collection of fairy tales that featured in the final novel, one of which was auctioned to raise money for the Children's High Level Group, a fund for mentally disabled children in poor countries. Rowling also wrote an 800-word prequel in 2008 as part of a fundraiser organised by the bookseller Waterstones.

Universe

The Wizarding world in which Harry finds himself is both completely separate from and yet intimately connected to our own world. While the fantasy world of Narnia is an alternative universe and the Lord of the Rings’ Middle-earth a mythic past, the Wizarding world of Harry Potter exists alongside that of the real world and contains magical elements similar to things in the non-magical world.

Many of its institutions and locations are in towns and cities which are recognisable in the real world, such as London. It possesses a fragmented collection of hidden streets, overlooked and ancient pubs, lonely country manors and secluded castles that remain invisible to the non-magical population of Muggles.[16] Wizard ability is inborn, rather than learned. Most wizards send their children to Wizarding schools to learn the magical skills necessary to get along in the magical world. There is no educational equivalent to college or graduate school in the Wizarding world. After graduation from their magical school, students are considered fully-trained witches and wizards who are ready to take their places in the Wizarding World. It is possible for wizard parents to have children who are born with little or no magical ability at all (known as "Squibs"). Since one is either born a wizard or not, most wizards are unfamiliar with the Muggle world, and what they do know of the Muggle world is either inaccurate or patronising.[16]

Structure and genre

The novels are very much in the fantasy genre, and in many respects they are also bildungsromans, or coming of age novels.[17] They can also be considered to be part of the British children's boarding school genre, which includes Enid Blyton's Malory Towers, St Clare's and the Naughtiest Girl series, and Frank Richards's Billy Bunter novels.[18] The Harry Potter books are predominantly set in Hogwarts, a fictional British boarding school for wizards, where the curriculum includes the use of magic.[18] In this sense they are "in a direct line of descent from Thomas Hughes's Tom Brown's School Days and other Victorian and Edwardian novels of British public school life".[19] They are also, in the words of Stephen King, "shrewd mystery tales",[20] and each book is constructed in the manner of a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery adventure. The stories are told from a third person limited point of view with very few exceptions (such as the opening chapters of Philosopher's Stone and Deathly Hallows and the first two chapters of Half-Blood Prince).

In the middle parts of each book, Harry must struggle with the new problems introduced, and dealing with them often involves the need to violate some school rules — the penalties, in case of being caught out, being disciplinary punishments set out in the Hogwarts regulations (in which, too, the Harry Potter books follow many precedents in the boarding school sub-genre).[18] However, the stories reach their climax in the summer term, near or just after final exams, when events escalate far beyond in-school squabbles and struggles, and Harry must confront either Voldemort or one of his followers, the Death Eaters, with the stakes being literally a matter of life and death – a point underlined, as the series progresses, by one or more characters being actually killed off in each of the last four books.[21][22] In the aftermath, he learns important lessons through exposition and discussions with head teacher and mentor Albus Dumbledore.

This formula was completely broken in the final novel, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, in which Harry and his friends spend most of their time away from Hogwarts, and only return there to face Voldemort at the dénouement.[21] Completing the bildungsroman format, in this part Harry must grow up prematurely, losing the chance of a last year as a pupil in a school and needing to act as an adult, on whose decisions everybody else depends – the grown-ups included.[23]

Origins and publishing history

In 1990, J. K. Rowling was on a crowded train from Manchester to London when the idea for Harry suddenly "fell into her head". Rowling gives an account of the experience on her website saying:[24]

I had been writing almost continuously since the age of six but I had never been so excited about an idea before. I simply sat and thought, for four (delayed train) hours, and all the details bubbled up in my brain, and this scrawny, black-haired, bespectacled boy who did not know he was a wizard became more and more real to me.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone was completed in 1995 and the manuscript was sent off to several prospective agents.[25] The second agent she tried, Christopher Little, offered to represent her and sent the manuscript to Bloomsbury. After eight other publishers had rejected Philosopher's Stone, Bloomsbury offered Rowling a £2,500 advance for its publication.[26] Despite Rowling's statement that she did not have any particular age group in mind when beginning to write the Harry Potter books, the publishers initially targeted children aged nine to eleven.[27] On the eve of publishing, Rowling was asked by her publishers to adopt a more gender-neutral pen name in order to appeal to the male members of this age group, fearing that they would not be interested in reading a novel they knew to be written by a woman. She elected to use J. K. Rowling (Joanne Kathleen Rowling), using her grandmother's name as her second name because she has no middle name.[28]

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone was published by Bloomsbury, the publisher of all Harry Potter books in the United Kingdom, on June 30, 1997. It was released in the United States on September 1, 1998 by Scholastic — the American publisher of the books — as Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone,[29] after Rowling had received USD$105,000 for the American rights — an unprecedented amount for a children's book by a then-unknown author.[30] Fearing that American readers would not associate the word "philosopher" with a magical theme (as a Philosopher's Stone is alchemy-related), Scholastic insisted that the book be given the title Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone for the American market.

With estimates of its global sales exceeding 110 million copies, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone has become one of the best-selling books in history.[31]

The second book, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets was originally published in the UK on July 2, 1998[32] and in the US on June 2, 1999.[33] Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban was then published a year later in the UK on July 8, 1999[34] and in the US on September 8, 1999.[35] Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire was published on July 8, 2000 at the same time by Bloomsbury and Scholastic.[36] Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix is the longest book in the series at 766 pages in the UK version and 870 pages in the US version.[37] It was published worldwide in English on June 21, 2003.[38] Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was published on July 16, 2005,[39] and 11 million copies in the first 24 hours of its release were sold worldwide.[40] The seventh and final novel, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, was published July 21, 2007.[41] The book sold 11 million copies in the first 24 hours of release, breaking down to 2.7 million copies in the UK and 8.3 million in the US.[42]

Translations

The series has been translated into 65 languages,[43] placing Rowling among the most translated authors in history.[44] The first translation was into American English, as many words and concepts used by the characters in the novels may have been misleading to a young American audience.[45][46] Subsequently, the books have seen translations to diverse languages such as Ukrainian, Hindi, Bengali, Welsh, Afrikaans, and Vietnamese. The first volume has been translated into Latin and even Ancient Greek,[47] making it the longest published work in Ancient Greek since the novels of Heliodorus of Emesa in the 3rd century AD.[48]

Some of the translators hired to work on the books were quite well-known before their work on Harry Potter, such as Viktor Golyshev, who oversaw the Russian translation of the series' fifth book. Golyshev was previously best known for translating the works of William Faulkner and George Orwell;[49] his tendency to snub the Harry Potter books in interviews and refer to them as inferior literature may be the reason he did not return to work on later books in the series. The Turkish translation of books two to seven was undertaken by Sevin Okyay, a popular literary critic and cultural commentator.[50] For reasons of secrecy, translation can only start when the books are released in English; thus there is a lag of several months before the translations are available. This has led to more and more copies of the English editions being sold to impatient fans in non-English speaking countries. Such was the clamour to read the fifth book that its English language edition became the first English-language book ever to top the bestseller list in France.[51]

Completion of the series

In December 2005, Rowling stated on her web site, "2006 will be the year when I write the final book in the Harry Potter series."[52] Updates then followed in her online diary chronicling the progress of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, with the release date of July 21, 2007. The book itself was finished on January 11, 2007 in the Balmoral Hotel, Edinburgh, where she scrawled a message on the back of a bust of Hermes. It read: “J. K. Rowling finished writing Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in this room (652) on January 11, 2007.”[53]

Rowling herself has stated that the last chapter of the final book (in fact, the epilogue) was completed "in something like 1990".[54][55] In June 2006, Rowling, on an appearance on the British talk show Richard & Judy, announced that the chapter had been modified as one character "got a reprieve" and two others who previously survived the story had in fact been killed. She also said she could see the logic in killing off Harry to stop other writers from writing books about Harry's life after Hogwarts.[56] On March 28, 2007, the cover art for the Bloomsbury Adult and Child versions and the Scholastic version were released.[57]

After Deathly Hallows

Rowling spent seventeen years writing the seven Harry Potter books. In a 2000 interview through Scholastic, her American publisher, Rowling stated that there is not a university after Hogwarts. Concerning the series continuing past book seven, she stated, "I will not say never, but I have no plans to write an eighth book."[58] She has since said that if she does write an eighth book Harry Potter will not be the central character, as his story has been told, and that she would not begin such a project for at least ten years.[59]

When asked about writing other Harry Potter-related books similar to Quidditch Through the Ages and Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, she has said that she might consider doing this with proceeds donated to charity, as was the case with those two books. Another suggestion is an encyclopaedia-style tome containing information that never made it into the series, also for charity.[60] She has revealed she is currently penning two books, one for children and one not for children.[61]

In a 90-minute live Web chat, Rowling revealed[62] what several of the characters did in the years between the conclusion of the book and the epilogue. Rowling has written an 800-word prequel adventure to the Harry Potter series for Waterstone's "What's Your Story" postcard book, which was auctioned for charity and fetched £25,000. Rowling has stressed that she is not intending to write a full length prequel.[63]

Achievements

Cultural impact

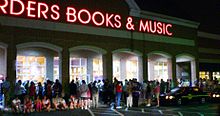

The series has also garnered a large following of fans. So eager were these fans for the latest series release that bookstores around the world began holding events to coincide with the midnight release of the books, beginning with the 2000 publication of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. The events, commonly featuring mock sorting, games, face painting, and other live entertainment have achieved popularity with Potter fans and have been highly successful in attracting fans and selling books with nearly nine million of the 10.8 million initial print copies of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince sold in the first 24 hours.[64][65] Besides meeting online through blogs, podcasts, and fansites, Harry Potter super-fans can also meet at Harry Potter symposia. The word Muggle has spread beyond its Harry Potter origins, used by many groups to indicate those who are not aware or are lacking in some skill. In 2003, "Muggle", entered the Oxford English Dictionary with that definition.[66] The Harry Potter fandom has embraced podcasts as a regular, often weekly, insight to the latest discussion in the fandom. Apple Inc. has featured two of the podcasts, MuggleCast and PotterCast.[67] Both have reached the top spot of iTunes podcast rankings and have been polled one of the top 50 favourite podcasts.[68] The series has also gathered adult fans, leading to the release of two editions of each Harry Potter book, identical in text but with one edition's cover artwork aimed at children and the other aimed at adults.[69]

Awards and honours

The Harry Potter series have been the recipients of a host of awards since the initial publication of Philosopher's Stone including four Whitaker Platinum Book Awards (all of which were awarded in 2001),[70] three Nestlé Smarties Book Prizes (1997–1999),[70] two Scottish Arts Council Book Awards (1999 and 2001),[70] the inaugural Whitbread children's book of the year award[70] (1999), the WHSmith book of the year (2006),[70] among others. In 2000, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban was nominated for Best Novel in the Hugo Awards while in 2001, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire won said award.[70] Honours include a commendation for the Carnegie Medal (1997),[70] a short listing for the Guardian Children's Award (1998),[70] and numerous listings on the notable books, editors' Choices, and best books lists of the American Library Association, New York Times, Chicago Public Library, and Publishers Weekly.[71]

Commercial success

The popularity of the Harry Potter series has translated into substantial financial success for Rowling, her publishers, and other Harry Potter related license holders. This success has made Rowling the first and thus far only billionaire author.[72] The books have sold more than 375 million copies worldwide and have also given rise to the popular film adaptations produced by Warner Bros., all of which have been successful in their own right with the first, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, ranking number four on the inflation-unadjusted list of all-time highest grossing films and the other four Harry Potter films each ranking in the top 20.[73] The films have in turn spawned eight video games and have in conjunction with them led to the licensing of more than 400 additional Harry Potter products (including an iPod) that have, as of July 2005, made the Harry Potter brand worth an estimated 4 billion US dollars and J. K. Rowling a US dollar billionaire,[74] making her, by some reports, richer than Queen Elizabeth II,[75][76] however, Rowling has stated that this is false.[77]

On April 12, 2007, Barnes & Noble declared that Deathly Hallows has broken its pre-order record, with more than 500,000 copies pre-ordered through its site.[78] For the release of Goblet of Fire, 9000 FedEx trucks were used with no other purpose than to deliver the book.[79] Together, Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble pre-sold more than 700,000 copies of the book.[79] In the United States, the book's initial printing run was 3.8 million copies.[79] This record statistic was broken by Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, with 8.5 million, which was then shattered by Half-Blood Prince with 10.8 million copies.[80] 6.9 million copies of Prince were sold in the U.S. within the first 24 hours of its release; in the United Kingdom more than two million copies were sold on the first day.[81] The initial print run for Deathly Hallows was 12 million copies, and more than a million were pre-ordered through Amazon and Barnes & Noble.[82]

In November 2007, the magazine Advertising Age estimated the total value of the Harry Potter brand at roughly $15 billion (£7 billion). Only a fraction of this value was derived from the book sales. The rest was drawn from a wide range of ancillary works, from films to video games to merchandising.[12]

Criticism, praise, and controversy

Literary criticism

Early in its history, Harry Potter received positive reviews, which helped the series to grow a large readership. Upon its publication, the first volume, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, was praised by most of Britain's major newspapers: The Mail on Sunday rated it as "the most imaginative debut since Roald Dahl"; a view echoed by the Sunday Times ("comparisons to Dahl are, this time, justified"), while The Guardian called it "a richly textured novel given lift-off by an inventive wit" and The Scotsman said it had "all the makings of a classic".[83]

By the time of the release of the fifth volume, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, the books began to receive strong criticism from a number of literary scholars. Yale professor, literary scholar and critic Harold Bloom raised criticisms of the books' literary merits, saying, “Rowling's mind is so governed by clichés and dead metaphors that she has no other style of writing."[84] A. S. Byatt authored a New York Times op-ed article calling Rowling's universe a “secondary world, made up of patchworked derivative motifs from all sorts of children's literature ... written for people whose imaginative lives are confined to TV cartoons, and the exaggerated (more exciting, not threatening) mirror-worlds of soaps, reality TV and celebrity gossip".[85]

The critic Anthony Holden wrote in The Observer on his experience of judging Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban for the 1999 Whitbread Awards. His overall view of the series was negative — "the Potter saga was essentially patronising, conservative, highly derivative, dispiritingly nostalgic for a bygone Britain," and he speaks of "pedestrian, ungrammatical prose style.[86]"

By contrast, author Fay Weldon, while admitting that the series is "not what the poets hoped for," nevertheless goes on to say, "but this is not poetry, it is readable, saleable, everyday, useful prose".[87] The literary critic A.N. Wilson praised the Harry Potter series in 'The Times', stating: "There are not many writers who have JK’s Dickensian ability to make us turn the pages, to weep — openly, with tears splashing — and a few pages later to laugh, at invariably good jokes...We have lived through a decade in which we have followed the publication of the liveliest, funniest, scariest and most moving children’s stories ever written.[88] Charles Taylor of Salon.com, who is primarily a movie critic,[89] took issue with Byatt's criticisms in particular. While he conceded that she may have "a valid cultural point — a teeny one — about the impulses that drive us to reassuring pop trash and away from the troubling complexities of art", he rejected her claims that the series is lacking in serious literary merit and that it owes its success merely to the childhood reassurances it offers. Taylor stressed the progressively darker tone of the books, shown by the murder of a classmate and close friend and the psychological wounds and social isolation each causes. Taylor also pointed out that Philosopher's Stone, said to be the most lighthearted of the seven published books, disrupts the childhood reassurances that Byatt claims spur the series' success: the book opens with news of a double murder, for example.[90]

Stephen King called the series "a feat of which only a superior imagination is capable," and declared "Rowling's punning, one-eyebrow-cocked sense of humour" to be "remarkable." However, he wrote that despite the story being "a good one," he is "a little tired of discovering Harry at home with his horrible aunt and uncle," the formulaic beginning of all seven books.[20] King has also joked that "Rowling's never met an adverb she did not like!" He does however predict that Harry Potter "will indeed stand time's test and wind up on a shelf where only the best are kept; I think Harry will take his place with Alice, Huck, Frodo, and Dorothy and this is one series not just for the decade, but for the ages."[91]

Cultural criticism

Although Time magazine named Rowling as a runner-up for its 2007 Person of the Year award, noting the social, moral, and political inspiration she has given her fandom,[92] cultural criticisms of the series have been mixed. Washington Post book critic Ron Charles opined in July 2007 that the large numbers of adults reading the Potter series but few other books may represent a "bad case of cultural infantilism", and that the straightforward "good vs. evil" theme of the series is "childish." He also argued "through no fault of Rowling's," the cultural and marketing "hysteria" marked by the publication of the later books "trains children and adults to expect the roar of the coliseum, a mass-media experience that no other novel can possibly provide."[93]

Jenny Sawyer wrote in the July 25, 2007 Christian Science Monitor that the books represent a "disturbing trend in commercial storytelling and Western society" in that stories "moral center have all but vanished from much of today's pop culture.... after 10 years, 4,195 pages, and over 375 million copies, J. K. Rowling's towering achievement lacks the cornerstone of almost all great children's literature: the hero's moral journey." Harry Potter, Sawyer argues, neither faces a "moral struggle" nor undergoes any ethical growth, and is thus "no guide in circumstances in which right and wrong are anything less than black and white."[94]

Chris Suellentrop made a similar argument in a November 8, 2002 Slate Magazine article, likening Potter to a "a trust-fund kid whose success at school is largely attributable to the gifts his friends and relatives lavish upon him." Noting that in Rowling's fiction, magical ability potential is "something you are born to, not something you can achieve", Suellentrop wrote that Dumbledore's maxim that "It is our choices that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities" is hypocritical, as "the school that Dumbledore runs values native gifts above all else."[95] In an August 12, 2007 New York Times review of The Deathly Hallows, however, Christopher Hitchens praised Rowling for "unmooring" her "English school story" from literary precedents "bound up with dreams of wealth and class and snobbery", arguing that she had instead created "a world of youthful democracy and diversity".[96]

Controversies

The books have been the subject of a number of legal proceedings, stemming either from claims by American Christian groups that the magic in the books promotes witchcraft among children, or from various conflicts over copyright and trademark infringements. The popularity and high market value of the series has led Rowling, her publishers, and film distributor Warner Bros. to take legal measures to protect their copyright, which have included banning the sale of Harry Potter imitations, targeting the owners of websites over the "Harry Potter" domain name, and suing author Nancy Stouffer to counter her accusations that Rowling had plagiarised her work.[97][98][99] Various religious conservatives have claimed that the books promote witchcraft and are therefore unsuitable for children,[100] while a number of critics have criticised the books for promoting various political agendas.[101][102]

Adaptations

In 1999, Rowling sold the film rights to the first four Harry Potter books to Warner Bros. for a reported £1 million (US$1,982,900).[103] A demand Rowling made was that the principal cast be kept strictly British, nonetheless allowing for the inclusion of many Irish actors such as the late Richard Harris as Dumbledore, and for casting of French and Eastern European actors in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire where characters from the book are specified as such.[104] After considering many directors such as Steven Spielberg, Terry Gilliam, Jonathan Demme, and Alan Parker, on March 28, 2000, Chris Columbus was appointed as director for Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (titled "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone" in the United States), with Warner Bros. citing his work on other family films such as Home Alone and Mrs. Doubtfire as influences for their decision.[105] After extensive casting,[106] filming began in October 2000 at Leavesden Film Studios and in London itself, with production ending in July 2001.[107] Philosopher's Stone was released on November 16, 2001. Just three days after Philosopher's Stone's release, production for Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, also directed by Columbus, began, finishing in Summer 2002. The film was released on November 15, 2002.[108]

Chris Columbus declined to direct Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, only acting as producer. Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón took over the job, and after shooting in 2003, the film was released on June 4, 2004. Due to the fourth film beginning its production before the third's release, Mike Newell was chosen as the director for Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire,[109] released on November 18, 2005. Newell declined to direct the next movie, and British TV director David Yates was chosen for Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, which began production on January 2006,[110] and was released on July 11, 2007. Yates is in the middle of directing Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince,[111] for release on July 17, 2009.[11] In March 2008, Warner Bros. announced that the final instalment of the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, would be filmed in two segments, with part one released in November 2010 and part two released in May 2011. Yates is expected again return to direct both films.[112] The Harry Potter films were huge box office hits, with all five on the 20 highest-grossing films worldwide.[113]

Opinions of the films generally divide book fans right down the middle, with one group preferring the more faithful approach of the first two films, and another group preferring the more stylised character-driven approach of the later films.[114] Rowling has been constantly supportive of the films,[115][116][117] and evaluated Order of the Phoenix as "the best one yet" in the series.[118] She wrote on her web site of the changes in the book-to-film transition, "It is simply impossible to incorporate every one of my storylines into a film that has to be kept under four hours long. Obviously films have restrictions novels do not have, constraints of time and budget; I can create dazzling effects relying on nothing but the interaction of my own and my readers’ imaginations".[119]

A musical based on the series is currently being planned, tentatively scheduled for a 2008 run in London's West End.[120] The Sunday Mirror reports that producers are hoping to have a "big-name composer" write the music. It has not yet been decided whether the production will tell the entire story, or focus on one particular sub-plot, though they do hope to include "spectacular flying scenes, live Quidditch and big showdowns with Voldemort".[121]

References

- ^ "Special stamps to mark Potter book release". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2007-05-22. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ Allsobrook, Dr. Marian (2003-06-18). "Potter's place in the literary canon". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ^ Flood, Alison (2008-06-17). "Potter tops 400 million sales". theBookseller.com. The Bookseller. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ^ Flood, Alison (2008-06-17). "Potter tops 400 million sales". theBookseller.com. The Bookseller. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ^ Pauli, Michelle. "June date for Harry Potter 5". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ^ "Potter 'is fastest-selling book ever". BBC News. 2007-08-04. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ "Harry Potter finale sales hit 11 m". BBC News. 2007-7-23. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Publication Date for Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows". Joanne Rowling. 2006. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ McLaren, Elsa (2007-03-15). "Harry Potter's final adventure to get record print run". The Times. Times Online. Retrieved 2007-03-27.

- ^ Kellner, Tomas; Watson, Julie (February 29, 2004). "J. K. Rowling And The Billion-Dollar Empire". Forbes. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince". Market Watch. 2008-08-14. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ a b "Harry Potter, the $15 billion man". exchange4media. 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- ^ "Book review: 'Deathly Hallows'". seacoastonline.com. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ "How Rowling conjured up millions". BBC. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ^ "Comic Relief : Quidditch through the ages". Albris. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ^ a b "A Muggle's guide to Harry Potter". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2004-05-28. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ Anne Le Lievre, Kerrie (2003). "Wizards and wainscots: generic structures and genre themes in the Harry Potter series". CNET Networks, Inc., a CBS Company. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ^ a b c "Harry Potter makes boarding fashionable". British Broadcasting Corporation. 1999. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ^ Ellen Jones, Leslie (2003). J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313323409.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b ""Wild About Harry"". New York Times. July 23, 2000.

- ^ a b Grossman, Lev. "Harry Potter's Last Adventure". Time Inc. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ^ "Two characters to die in last 'Harry Potter' book: J.K. Rowling". CBC. 2006. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ^ "Press views: The Deathly Hallows". Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ Final Harry Potter book set for release, Euskal Telebista, 2007-07-15, retrieved 2008-08-21

- ^ Lawless, John (2005). "Nigel Newton". The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ "J. K. Rowling". kidsreads.com. 1998–2008. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Savill, Richard (2006). "Harry Potter and the mystery of J K's lost initial". Accio Quote!. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ ISBN 9780590353427

- ^ Rozhon, Tracie. "A Brief Walk Through Time at Scholastic". The New York Times. The New York Timesdate=2007-04-21. p. C3. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ^ "All-Time Bestselling Children's Books". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ^ ISBN 0-7475-3849-2

- ^ ISBN 0-439-06486-4

- ^ ISBN 0-7475-4215-5

- ^ ISBN 0-439-13635-0

- ^ UK: ISBN 0-7475-4624-X and US: ISBN 0-439-13959-7

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Internet Pirates". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ^ UK: ISBN 0-7475-5100-6 and US: ISBN 0-439-35806-X

- ^ UK: ISBN 0-7475-8108-8 and US: ISBN 0-439-78454-9

- ^ "Harry Potter finale sales hit 11 m". BBC News. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ^ UK: ISBN 1-5519-2976-7 and US: ISBN 0-545-01022-5

- ^ "Harry Potter finale sales hit 11 m". British Broadcasting Corporation. July 23, 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ Braithwaite, Alyssa (2007-07-21). "What now for Harry Potter fans?". Daily Telegraph. pp. 12–27. Retrieved 2006-07-03.

- ^ KMaul (2005). "Guinness World Records: L. Ron Hubbard Is the Most Translated Author". thebookstandard.com. The Book Standard. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ^ "Differences in the UK and US Versions of Four Harry Potter Books". FAST US-1. January 21, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ "Harry Potter British/American text comparison". Comcast.net. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (2006). "Harry Potter in Greek". Andrew Wilson. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- ^ Castle, Tim (December 2, 2004). "Harry Potter? It's All Greek to Me". Reuters. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- ^ Steven Goldstein (2004). "Translating Harry — Part I: The Language of Magic". GlobalByDesign. GlobalByDesign. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ^ EMRAH GÜLER (2005). "Not lost in translation: Harry Potter in Turkish". The Turkish Daily News. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Staff Writer (July 1, 2003). "OOTP is best seller in France — in English!". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- ^ Entertainment News Staff (December 28, 2005). "The End of Harry Potter - "For 2006 will be the year when I write the final book in the Harry Potter series", the author declared". Softpedia. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ "Potter author signs off in style". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2007-02-02.

- ^ ""Rowling to kill two in final book"". BBC News. 2006-06-27. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ ""Harry Potter and Me"". BBC News. 2001-12-28. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ "JKR On Richard & Judy – Transcript". Mugglenet.com. 1999–2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Cover Art". the-leaky-cauldron.org. 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- ^ "Transcript of JKR's live interview on Scholastic.com". Scholastic Inc. 1996–2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ JK Rowling hints at eighth Potter, British Broadcasting Corporation, 2007-12-30, retrieved 2008-01-11

- ^ "A new chapter for Harry Potter and JK". The Telegraph. 2007-05-12. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ "Potter author 'penning two books'". BBC News. 2007-07-27. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ "Rowling Answers Fans' Final Questions". MSN Entertainment. 2007-07-30. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ "Harry Potter Prequel". Lord of the Web. June 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ Freeman, Simon (July 18, 2005). "Harry Potter casts spell at checkouts". Times Online. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ^ "Potter book smashes sales records". British Broadcasting Corporation. July 18, 2005. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ^ Meg McCaffrey (May 1, 2003). "'Muggle' Redux in the Oxford English Dictionary". School Library Journal. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ^ "Book corner: Secrets of Podcasting". Apple Inc. 2005-09-08. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

- ^ "Mugglenet.com Taps Limelight's Magic for Podcast Delivery of Harry Potter Content". PR Newswire. 2005-11-08. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

- ^ "Harry Potter at Bloomsbury Publishing — Adult and Children Covers". Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Harry Potter Books". Mugglenet. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ Levine, Arthur (2001 - 2005). "Awards". Arthur A. Levine Books. Retrieved 2006-05-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Watson, Julie (February 26, 2004), J. K. Rowling And The Billion-Dollar Empire, Forbes, retrieved 2007-12-03

{{citation}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "All Time Worldwide Box Office Grosses". Box Office Mojo, LLC. 1998–2008. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ "The World's Billionaires:#891 Joanne (JK) Rowling". Forbes. March 8, 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ^ "J. K. Rowling Richer than the Queen". British Broadcasting Corporation. April 27, 2003. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ^ "Harry Potter Brand Wizard". Business Week. July 21, 2005. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ^ "Rowling joins Forbes billionaires". BBC. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- ^ "New Harry Potter breaks pre-order record". RTÉ.ie Entertainment. 2007-04-13. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- ^ a b c Fierman, Daniel (2005-08-31). "Wild About Harry". Entertainment Weekly. ew.com. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

When I buy the books for my grandchildren, I have them all gift wrapped but one...that's for me. And I have not been 12 for over 50 years.

- ^ "Harry Potter hits midnight frenzy". CNN. CNN. 2005-07-15. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- ^ "Worksheet: Half-Blood Prince sets UK record". British Broadcasting Corporation Newsround. British Broadcasting Corporation. 2005-07-20. Retrieved 2007-01-19.

- ^ "Record print run for final Potter". British Broadcasting Corporation. British Broadcasting Corporation. 2007-03-15. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, JK Rowling (1998). Bloomsbury. p. 253. ISBN 978-1855496507.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Bloom, Harold (September 24, 2003). "Dumbing down American readers". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2006-06-20.

- ^ Byatt, A.S. (July 7, 2003). "Harry Potter and the Childish Adult". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ^ Holden, Anthony (June 25, 2000). "Why Harry Potter does not cast a spell over me". The Observer. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ^ Allison, Rebecca (July 11, 2003). "Rowling books 'for people with stunted imaginations'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ^ Manthrope, Rowland (July 29, 2007). "A farewell to charms". The Observer. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ^ "Salon Columnist". Salon.com. 2000. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ^ Taylor, Charles (July 8, 2003). "A. S. Byatt and the goblet of bile". Salon.com. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ^ Fox, Killian (2006-12-31). "JK Rowling:The mistress of all she surveys". Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- ^ "Person of the Year 2007 Runners-Up: J. K. Rowling". Time Magazine. December 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ Charles, Ron (July 15, 2007). "Harry Potter and the Death of Reading". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ^ Sawyer, Jenny (July 25, 2007). "Missing from 'Harry Potter" – a real moral struggle". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ^ Suellentrop, Chris (November 8, 2002). "Harry Potter: Fraud". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (August 12, 2007). "The Boy Who Lived". The New York Times. p. 2. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ^ "SCHOLASTIC, INC., J. K. ROWLING, and TIME WARNER ENTERTAINMENT COMPANY, L.P., Plaintiffs/Counterclaim Defendants, -against- NANCY STOUFFER: UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK". ICQ. September 17, 2002. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ Kieren McCarthy (2000). "Warner Brothers bullying ruins Field family Xmas". The Register. The Register. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- ^ "Fake Harry Potter novel hits China". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2002-07-04. Retrieved 2007-03-11.

- ^ Ted Olsen. "Opinion Roundup: Positive About Potter". Cesnur.org. Retrieved 2007-07-06.

- ^ Steve Bonta (2002-01-28). "Tolkien's Timeless Tale". The New American. 18 (2).

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Liddle, Rod (July 21, 2007). "Hogwarts is a winner because boys will be sexist neocon boys". The Times. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ "WiGBPd About Harry". Australian Financial Review. 2000-07-19. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone". Guardian Unlimited. 2001-11-16. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ Bran Linder (2000-03-28). "Chris Columbus to Direct Harry Potter". IGN. Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- ^ "DANIEL RADCLIFFE, RUPERT GRINT AND EMMA WATSON BRING HARRY, RON AND HERMIONE TO LIFE FOR WARNER BROS. PICTURES'"HARRY POTTER AND THE SORCERER'S STONE"". Warner Brothers. 2000-08-21. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ Greg Dean Schmitz. "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (2001)". Yahoo!. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002)". Yahoo! Inc. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ^ "Goblet Helmer Confirmed". IGN. 2003-08-11. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ Daly, Steve (2007-04-06). "'Phoenix' Rising". Entertainment Weekly. Entertainment Weekly. p. 28. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- ^ Spelling, Ian (2007-05-03). "Yates Confirmed For Potter VI". Sci Fi Wire. Sci Fi Wire. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- ^ "Final 'Harry Potter' book will be split into two movies". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. March 13, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

{{cite web}}: Text "Jeff Boucher" ignored (help) - ^ "All Time Worldwide Box Office Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ "Harry Potter: Books vs films". digitalspy.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ^ "Potter Power!". Time For Kids. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (2004-05-27). "New 'Potter' movie sneaks in spoilers for upcoming books". USA Today. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ "JK 'loves' Goblet Of Fire movie". BBC Newsround. 2005-11-07. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ Grint, Rupert, David Heyman, Emerson Spartz (July 8). OOTP US Premiere red carpet interviews. MuggleNet. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

{{cite AV media}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ Rowling, J. K. "How did you feel about the POA filmmakers leaving the Marauder's Map's background out of the story? (A Mugglenet/Lexicon question)". jkrowling.com. J. K. Rowling. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ "'Harry Potter' Musical to Open Next Year". Hollywood.com, Inc. August 26, 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ Hamilton, Sean. "Harry Potter... The Musical". The Sunday Mirror. Retrieved 2007-08-27.