Józef Piłsudski: Difference between revisions

the Polish name seems to be Zułów, not Żułów |

→Life: Thank you, Piotr Konieczny aka Prokonsul Piotrus, for catching my typo of the Polish spelling. Since this is Eng WP, the PL geographical topnym is not necessary. Also re-added factual info. |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

===Early life=== |

===Early life=== |

||

[[Image:Piludski w szkole.jpg|thumb|100px|left|thumb|Piłsudski as a schoolboy.]] |

[[Image:Piludski w szkole.jpg|thumb|100px|left|thumb|Piłsudski as a schoolboy.]] |

||

Józef Piłsudski was born in 1867 in the village of [[ |

Józef Piłsudski was born in 1867 in the Lithuanian village of [[Zalavas]], at that time in the [[Russian Empire]], in an area that had been part of the old [[Grand Duchy of Lithuania]], itself a component of the [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth]] before [[partitions of Poland|the latter's partitions]].<ref name="Poland.gov">{{cite web | title=Józef Piłsudski (1867 - 1935) | work=Poland.gov | url=http://poland.gov.pl/Jozef,Pilsudski,(1867-1935),1972.html | accessmonthday = April 23 | accessyear=2006 }}</ref> He was born into the ''[[szlachta]]'' (noble) [[Piłsudski (family)|Piłsudski]] family, who cherished Polish patriotic traditions;<ref name="Poland.gov"/><ref name="Urb 13-15">{{pl icon}} [[Bohdan Urbankowski]], ''Józef Piłsudski: marzyciel i strateg'' (Józef Piłsudski: Dreamer and Strategist), ''tom pierwszy'' (volume one), Warsaw, Wydawnictwo ALFA, 1997, ISBN 8370019145, pp. 13-15.</ref> the family has been characterized either as Polish<ref name="HD">[[Jerzy Jan Lerski]], ''Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945'', Greenwood Press, 1996, ISBN 0313260079, [http://books.google.com/books?id=S6aUBuWPqywC&pg=PA439&dq=pilsudski+Polish+noble&ei=01QNR_SuO6jA7AKop8CuBg&sig=Bldt8emkmGuNNIdY6sjE2dEWZMg Google Print, p.449]</ref> or as [[Polonized]]-[[Lithuanian]].<ref>{{cite web |

||

|title= A History of Eastern Europe Crisis and Change |

|title= A History of Eastern Europe Crisis and Change |

||

|author=[[Robert Bideleux]], [[Ian Jeffries]] |

|author=[[Robert Bideleux]], [[Ian Jeffries]] |

||

Revision as of 02:13, 17 November 2007

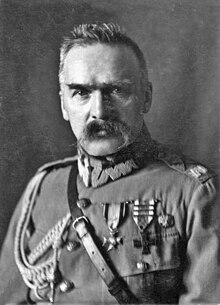

Józef Klemens Piłsudski | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chief of State of the Republic of Poland | |

| In office November 18, 1918 – December 9, 1922 | |

| Prime Minister | under presidents: Jędrzej Moraczewski, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Leopold Skulski, Władysław Grabski, Wincenty Witos, Antoni Ponikowski, Artur Śliwiński, Julian Nowak |

| Preceded by | Independence |

| Succeeded by | President Gabriel Narutowicz |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 5, 1867 |

| Died | May 12, 1935 (aged 67) |

| Political party | None (Formerly PPS) |

| Spouse(s) | Maria Piłsudska (d. 1921) Aleksandra Piłsudska |

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (ⓘ, December 5, 1867 – May 12, 1935) was a Polish statesman, Field Marshal, first Chief of State (1918–1922) and dictator (1926–1935) of the Second Polish Republic, as well as head of its armed forces. Born into a noble family with traditions dating back to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, from the middle of World War I until his death Piłsudski was the major influence on Poland's government and foreign policy, and an important figure in European politics.[1] He is considered largely responsible for Poland having regained her independence in 1918, 123 years after the last partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795.

Piłsudski desired the independence of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from his youth, and in his early political life was an influential member and later leader of the Polish Socialist Party. He considered the Russian Empire to be the most formidable obstacle to Polish independence, and worked with Austro-Hungary and Germany to ensure Russia's defeat in World War I. Later in the war, he withdrew his support from the Central Powers to work with the Triple Entente for the defeat of the Central Powers. After World War I, during the Polish-Soviet War, he commanded the 1920 Kiev Offensive and the Battle of Warsaw. From November 1918 (when Poland regained independence) until 1922, he was Poland's Chief of State (Naczelnik Państwa).

In 1923, as the Polish government became dominated by Piłsudski's chief opponents, the National Democrats, he withdrew from active politics. Three years later, however, he returned to power in the May 1926 coup d'état, becoming de facto dictator of Poland. From then until his death in 1935, he concerned himself primarily with military and foreign affairs. To this day, Piłsudski is held in high regard by most of the Polish public.[2]

Life

Early life

Józef Piłsudski was born in 1867 in the Lithuanian village of Zalavas, at that time in the Russian Empire, in an area that had been part of the old Grand Duchy of Lithuania, itself a component of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth before the latter's partitions.[3] He was born into the szlachta (noble) Piłsudski family, who cherished Polish patriotic traditions;[3][4] the family has been characterized either as Polish[5] or as Polonized-Lithuanian.[6] [a]

Piłsudski attended school in Vilnius (Polish: Wilno), not an especially diligent student.[7] As a boy, along with his brothers Adam, Bronisław and Jan, he was introduced by his mother, Maria née Bilewicz, to Polish history and literature, which were suppressed by the Russian authorities.[8] His father, likewise named Józef, had fought in the January 1863 Uprising against the Russian occupation of Poland.[3] The family resented the Russian government's Russification policies; young Józef profoundly disliked having to attend Russian Orthodox Church services.[8]

In 1885 Piłsudski began studying medicine at the University of Kharkov (modern Kharkiv, Ukraine), where he became involved with Narodnaya Vola, part of the Russian Narodniki revolutionary movement.[9] In 1886 he was suspended for participating in student demonstrations.[3] He was rejected by the University of Dorpat (now Tartu), Estonia, whose authorities had been informed of his political affiliation.[3] On March 22, 1887, he was arrested by the Tsarist authorities on a false[10] charge of plotting with Vilnius socialists to assassinate Tsar Alexander III. In fact, Piłsudski's main connection to the plot was the involvement in it of his elder brother, Bronisław Piłsudski.[11] Bronisław was sentenced to fifteen years' hard labor (katorga) in eastern Siberia.[11][12]

Józef Piłsudski received a milder sentence than his brother's: five years' exile to eastern Siberia, first at Kirinsk on the Lena River, later at Tunka.[3][12] As an exile, Piłsudski was allowed to work in an occupation of his choosing, although local officials decided that as a Polish noble he was not entitled to the 10-ruble pension received by most other exiles.[13]

While being transported in a prisoners' convoy to Siberia, he was held for several weeks at an Irkutsk prison. There he took part in a prisoners' "revolt": after one of the prisoners had insulted a guard and refused to apologize, he and other political prisoners were brutally beaten by the guards for their defiance;[14] Piłsudski lost two teeth and took part in a subsequent hunger strike until the authorities reinstated political prisoners' privileges that had been suspended after the "revolt."[14] For his involvement in this event, he was sentenced in 1888 to six months' imprisonment; he had to spend the first night of his incarceration in 40-degree-below-zero Siberian cold; this led to an illness that nearly killed him and to various health problems that would plague him throughout his life.[15] During his years of exile in Siberia, Piłsudski met many Sybiraks, including Bronisław Szwarce, who had almost become a leader of the January 1863 Uprising.[16]

"State criminal

JÓZEF PIŁSUDSKI, nobleman

DESCRIPTION:

Age 19 (1887)

Height 1 meter, 75 cm.

Face clear

Eyes grey

Hair dark-blond

Sideburns light-blond, sparse

Eyebrows dark-blond, fused

Beard dark-blond

Mustaches light-blond

Nose normal

Mouth normal

Teeth missing some

Chin round

Distinctive marks:

1) clear face, with eyebrows fused over nose,

2) wart at the end of right ear"

After his release in 1892, Piłsudski in 1893 joined the Lithuanian branch of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS),[3] forming the Lithuanian branch of PPS.[17] Initially he sided with the Socialists' more radical wing, but despite the ostensible internationalism of the Socialist movement, he always remained a Polish nationalist.[18] In 1894, as its chief editor, he began publishing a bibuła socialist newspaper, Robotnik (The Worker); he would also be one of its chief writers.[3][19][9] In 1895 he became a PPS leader, and took the position that doctrinal issues were of minor importance and that socialist ideology should be merged with nationalist ideology, as that combination offered the greatest chance of restoring Polish independence.[9]

In 1899, while an underground organizer, Piłsudski married a fellow socialist organizer, Maria Juszkiewiczowa, née Koplewska, but the marriage deteriorated when several years later Piłsudski began an affair with a younger socialist,[18] Aleksandra Zahorska. Maria died in 1921, and in October that year Piłsudski married Aleksandra. They had two daughters, Wanda (who later became a psychiatrist) and Jadwiga, but this marriage also had its troubles.[20]

In February 1900, after the Russian authorities found Robotnik's underground printing press in Łódź, Piłsudski was imprisoned at the Warsaw Citadel but, after feigning mental illness in May 1901, he managed to escape from a mental hospital at St. Petersburg with the help of Władysław Mazurkiewicz and others, fleeing to Galicia, then a region of Austria-Hungary.[3]

On the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), in summer 1904 Piłsudski traveled to Tokyo, Japan, where he unsuccessfully attempted to obtain that country's assistance for an uprising in Poland. He offered to supply Japan with intelligence in support of her war with Russia and proposed the creation of a Polish Legion from Poles,[21] conscripted into the Russian Army, who had been captured by Japan. He also suggested a "Promethean" project directed at liberating ethnic communities occupied by the Russian Empire — a goal that he later continued to pursue and that would be partly achieved only in 1991 with the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

Another notable Pole, Roman Dmowski, also traveled to Japan, where he argued against Piłsudski's plan, endeavoring to discourage the Japanese government from supporting at this time a Polish revolution which Dmowski felt would be doomed to failure.[22][21] Dmowski, himself a Polish patriot, would remain Piłsudski's political arch-enemy to the end of Piłsudski's life.[23] In the end, the Japanese offered Piłsudski only limited assistance; he received Japan's help in purchasing weapons and ammunition for the PPS and its combat organisation, while the Japanese declined the Legion proposal. This was much less than Piłsudski had hoped for.[21][3]

In fall 1904, Piłsudski founded an armed organization, the "Bojówki" ("combat teams"), to create an armed resistance movement against the Russian authorities.[22] PPS organized an increasing number of demonstrations (mostly in Warsaw); on October 28, 1904 Russian Cossack cavalry trampled one of the demonstrations, in revenge, on November 13 the 'bojówki' opened fire on the Russian police and military during a new demonstration.[24][22] First concentrating on fighting the spies and informants, in March 1905 'bojówki' started using bombs to assassinate selected members of Russian police.[25]

During the Russian Revolution of 1905, Piłsudski played a leading role in events in Congress Poland[22] In early 1905, he ordered the PPS to launch a general strike there. It involved some 400,000 workers, and lasted two months before it was broken by the Russian authorities.[22] In June 1905, Piłsudski ordered an uprising in Łódź.[22] During the "June Days", as the Łódź uprising came to be known, armed clashes broke out between gunmen loyal to Piłsudski's PPS and those loyal to Roman Dmowski's National Democratic Party (Endeks).[22] On December 22, 1905, Piłsudski called for all Polish workers to rise up; his call was widely ignored.[22] Unlike the Endeks, Piłsudski ordered the PPS to boycott the elections to the First Duma.[22] The decision to boycott the elections and to try to win Polish independence through uprisings caused much tension within the PPS, and, in November 1906, a faction of the party split off in protest of Piłsudski's leadership.[23] Piłsudski's faction was known as Old Faction or the Revolution Faction (Starzy, Frakcja Rewolucyjna), while their opponents were known as the Young Faction, Moderate Faction or the Left Wing (Młodzi, Frakcja Umiarkowana, Lewica). The Youngs sympathized with the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania and believed that the priority should be cooperation with Russian revolutionaries in toppling the tsardom and creating a socialist utopia first, and negotiation for independence would be easier later.[9] Piłsudski with his supporters from the revolutionary faction of the PPS, continued to plan a revolution against tsarist Russia[3] which would secure Polish independence first. By 1909 Piłsudski's faction would be the majority faction of PPS again, and Piłsudski would remain one of the most important leaders of PPS until the First World War.[26]

Piłsudski anticipated a coming European war and the need to organize the nucleus of a future Polish army that could help win Poland's independence from the three empires that had partitioned her out of political existence in the late 18th century. In 1906, Piłsudski, with the connivance and support of the Austrian authorities, founded a military school in Kraków for the training of Bojówki.[23] In 1906 alone, the 800-strong Bojówki, operating in five-man units in Congress Poland, killed 336 Russian officials; the number of casualties declined in the coming years; while the number of its members increased (to around 2,000 in 1908).[27][23] 'Bojówki' also assaulted Russian transports of money leaving Polish territories. In April/September 1908, the Bojówki robbed a Russian mail train carrying tax revenues from Warsaw to St. Petersburg.[23] Piłsudski, who took part in the raid at Bezdany near Vilna 1908, used those funds to aid his secret military organization. The loot from that single raid (200,812 rubles—or approximately $100,000) was a virtual fortune in contemporary Eastern Europe and equaled the amount Bojówki had looted in the two preceding years.[27]

In 1908, Piłsudski transformed the "Combat Teams" to "Związek Walki Czynnej" (Association for Active Struggle), headed by three of his associates, Władysław Sikorski, Marian Kukiel, and Kazimierz Sosnkowski.[23] One of the main purposes of ZWC was to train officers and NCOs for the future Polish army.[9] In 1910 two legal paramilitary organisations were created in the Austrian partitional zone (one in Lwów and the second in Cracow), to conduct training and lectures in military science. In 1912, Piłsudski became the Commander-in-Chief of Związek Strzelecki (under the codename 'Mieczysław').[3] With the permission of Austrian authorities, Piłsudski founded a series of "sporting clubs," followed by a riflemen's association that served as cover for training a Polish military force that grew by 1914 to 12,000 men.[23] In 1914, Piłsudski declared that "only the sword now carries any weight in the balance for the destiny of a nation".[23]

World War I

At a meeting in Paris in 1914, Piłsudski presciently declared that in the imminent war, for Poland to regain her independence, Russia must be beaten by the Central Powers (the Austro-Hungarian and German Empires), and the latter powers must in their turn be beaten by France, Britain and the United States.[28] By contrast, Roman Dmowski, leader of another faction of the Polish nationalist movement, believed the best way to achieve a unified and independent Poland was to support the Triple Entente against the Triple Alliance.[29]

At the outbreak of World War I, on August 3, in Kraków, Piłsudski formed a small cadre military unit, the First Cadre Company, from members of Związek Strzelecki and Polskie Drużyny Strzeleckie.[30][31] A cavarly unit under Władysław Belina-Prażmowski was sent on the same day to scout across the Russian border, even before the official declaration of war between Austro-Hungary and Russian Empire (which took place on August 6).[32] Piłsudski's goal was to send his forces north across the border into Russian Poland, into an area which the Russian army had evacuated, with the hope of breaking through to Warsaw and initiating a national uprising.[9][33] Using his limited forces, in those few early dates, he would back his orders with fictional "National Government in Warsaw",[34] and bend and stretch Austrian orders as much as possible, taking initiative, moving forward and establishing Polish institutions in liberated towns, when Austrians saw his forces as good only for scouting or supporting main Austrian formations.[35] Piłsudski's forces took the town of Kielce, capital of the Kielce Governorate, on 12 August, although the support from local populace was smaller then expected by Piłsudski.[36] Soon afterwards he officially established the Polish Legion, taking personal command of its First Brigade,[3] which he would lead successfully into several victorious battles.[9] He also secretly informed the British government in the fall of 1914 that his Legions would never fight against France or Britain — only against Russia.[33]

Within the Legions, Piłsudski decreed that personnel were to be addressed by the French-Revolution-inspired "Citizen," and he himself was referred to as "the Commandant" ("Komendant").[29] Piłsudski commanded an extreme respect and loyalty from his men[29] which would remain for years to come. The Polish Legion fought with distinction against Russia at the side of the Central Powers until 1917.

Soon after forming the Legions, also in 1914, Piłsudski set up another organization, the Polish Military Organisation (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa), which served as a precursor Polish intelligence agency and was designed to carry out espionage and sabotage missions.[9][33]

In mid-1916, in the aftermath of battle of Kostiuchnówka (4-6 July), where Polish Legions delayed Russian offensive at a cost of over 2000 casualties, Piłsudski demanded that Central Powers issue a guarantee of independence for Poland, he backed this demand with his resignation, as well as that of many of Legion's officers.[37] On November 5, 1916, the Central Powers proclaimed the "independence" of Poland, hoping for increasing number of Polish troops sent to the eastern front against Russia, relieving German forces to bolster the Western front. Piłsudski agreed to serve in the "Kingdom of Poland" created by the Central Powers, and served as minister of war in the newly created Polish Regency government.[29] In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution and the worsening situation of the Central Powers, Piłsudski increasingly took an uncompromising stance, insisting that his men not be treated as "German colonial troops" and only be used to fight Russia, and expecting the Central Powers to be defeated in the war, and not wishing to be allied to the losing side.[38]

In the aftermath of the Oath Crisis (July 1917), when Piłsudski forbade Polish soldiers to take an oath of loyalty to the Central Powers, he was arrested and imprisoned at Magdeburg; the Polish units were disbanded, and the men incorporated into the Austro-Hungarian army,[3][33] while the Polish Military Organization began attacking German targets.[9] Piłsudski's arrest greatly enhanced his reputation among Poles, many of whom began to see him as the most determined Polish leader, willing to fight against all the partitioning powers.[9]

On November 8, 1918, Piłsudski and his comrade, Colonel Kazimierz Sosnkowski, were released from Magdeburg and soon — like Vladimir Lenin before them — placed on a private train, bound for their national capital, as the increasingly desperate Germans hoped that Piłsudski would gather forces friendly to them.[33]

Rebuilding Poland

On November 11, 1918, in Warsaw, Piłsudski was appointed Commander in Chief of Polish forces by the Regency Council and was entrusted with creating a national government for the newly independent country; on that day (which would become Poland's Independence Day), he proclaimed an independent Polish state.[33] In that week he also negotiated the evacuation of the German garrison from Warsaw and of other German troops from the Ober-Ost (Eastern front); over 55,000 Germans would peacefully depart Poland immediately afterwards, leaving their weapons to the Poles; over 400,000 total would depart Polish territories in coming months.[33][39] On November 14, 1918, he was asked to provisionally supervise the running of the country. On November 22 he officially received, from the new government of Jędrzej Moraczewski, the title of Provisional Chief of State (Naczelnik Państwa) of renascent Poland.[3]

Various Polish military organizations and provisional governments (Regency Council in Warsaw, government of Ignacy Daszyński in Lublin and Polish Liquidation Committee in Kraków) bowed to Piłsudski, who set about forming a new coalition government. It was predominantly socialist and immediately introduced many reforms long proclaimed as necessary by the Polish Socialist Party (e.g. the 8-hour day, free school education, vote for women). This was absolutely necessary to avoid major unrest. However, Piłsudski believed that as head of state he must be above political parties,[9][33] and the day after his arrival in Warsaw, he met with old colleagues from underground days, who addressed him socialist-style as "Comrade" ("Towarzysz") and asked for support of their revolutionary policies. He declined to support any one party and did not form any political organization of his own; instead he advocated creating a coalition government.[9][40] He also set about organizing a Polish army out of Polish veterans of the German, Russian and Austrian armies.

In the days immediately after World War I, Piłsudski attempted to build a government in a shattered country. Much of former Russian Poland had been destroyed in the war, and systematic looting by the Germans had reduced the region's wealth by at least 10%.[41] A British diplomat who visited Warsaw in January 1919 reported: "I have nowhere seen anything like the evidences of extreme poverty and wretchedness that meet one's eye at almost every turn".[41] In addition, the country had to unify the different systems of law, economics, and administration in the former German, Austrian and Russian partitions of Poland into one; there were nine different legal systems, five currencies, 66 types of rail systems (with 165 models of locomotives), and other similar problems, which all had to be urgently consolidated.[41]

Wacław Jędrzejewicz, in Piłsudski: a Life for Poland, describes Piłsudski as very deliberate in his decision-making. He collected all available pertinent information, then took his time weighing it before arriving at a final decision. Piłsudski drove himself hard, working all day and, on a regimen of tea and chain-smoked cigarettes, all night.[41] He maintained a Spartan lifestyle, eating plain meals alone at an inexpensive restaurant, and became increasingly pale and thin.[41] Though Piłsudski was very popular with much of the Polish public, his reputation as a loner (the result of many years' underground work), of a man who distrusted almost everyone, led to strained relations with other Polish politicians.[18]

The first Polish government and Piłsudski were also distrusted in the West because Piłsudski had cooperated with the Central Powers in 1914-17 and because the governments of Ignacy Daszyński and Jędrzej Moraczewski were primarily socialist. It was not until January 1919, when the world-famed pianist and composer Ignacy Jan Paderewski became Prime Minister (also Foreign Minister) of a new government, that it was recognized in the West.[33] That still left two separate governments claiming to be the legitimate government of Poland: Piłsudski's in Warsaw, and Roman Dmowski's in Paris.[41] To ensure that Poland had a single government and to avert civil war, Paderewski met with Dmowski and Piłsudski and persuaded them to join forces, with Piłsudski acting as provisional president and supreme commander-in-chief while Dmowski and Paderewski represented Poland at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.[42]

Piłsudski often clashed with Dmowski, at variance with the latter's vision of the Poles as the dominant nationality in reborn Poland, and irked by Dmowski's attempt to send the Blue Army back to Poland through Danzig, Germany (modern Gdańsk, Poland).[43][44] On 5 January 1919 some of Dmowski's supporters (Marian Januszajtis-Żegota and Eustachy Sapieha) tried to carry out a coup against Piłsudski and Prime Minister Jędrzej Moraczewski, but failed.[45]

On 20 February 1919, Piłsudski's declared that he would return his powers to the newly elected Polish parliament (Sejm). However, the Sejm reinstated his office in the Small Constitution. The word Provisional was removed from the title; and Piłsudski would hold that office until 9 December 1922, when Gabriel Narutowicz was elected the first President of Poland.[3]

His major foreign policy initiative at this time was a proposed federation (to be called Międzymorze, "Between-Seas," stretching once again from the Baltic to the Black Sea) of Poland with the independent Baltic States, Belarus and Ukraine,[33] somewhat in emulation of the pre-partition Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth,[b] comprising a smaller Poland surrounded by a Polish-led federation of neighboring nations.[9] The plan was met by opposition from most of the intended members - who refused to compromise on their hard fought autonomy - as well as from the Allied powers;[46] a series of border conflicts soon broke out, including the Polish-Soviet War from 1919 to 1921, which involved Ukraine, the Polish-Lithuanian War in 1920, and border conflicts with Czechoslovakia that began in 1918;[9] according to the historian George Sanford, he came to realize this plan's infeasibility around 1920.[47]

Polish-Soviet War

In the chaotic aftermath of World War I, there was unrest on all Polish borders. Speaking of Poland's future frontiers, Piłsudski said: "All that we can gain in the west depends on the Entente — on the extent to which it may wish to squeeze Germany," while in the east "there are doors that open and close, and it depends on who forces them open and how far."[48] In 1918 in the east, Polish forces clashed with Ukrainian forces in the Polish-Ukrainian War, and Piłsudski's first orders as Commander in Chief of the Polish Army, on 12 November 1918, was to provide support for the Polish struggle in Lwów.[49] However, while Ukrainians were the first clear enemy, it soon became apparent that the split Ukrainian factions were not the real power in that region. In the coming months and certainly years, it became apparent that the Bolsheviks were in fact the most dangerous enemy not only of the newly reconstructed Polish nation, but also of the Ukrainians. Piłsudski was aware that the Bolsheviks were not friends of independent Poland, and that war with them was inevitable.[50] He viewed their advance west as a major issue but also considered Bolsheviks as less dangerous for Poland than their Russian-civil-war contenders,[51] as the White Russians - representative of the old Russian Empire, partitioner of Poland - were willing to accept only limited independence of Poland, likely in the borders similar to that of Congress Poland, and clearly objected to Ukrainian independence, crucial for Piłsudski's Międzymorze,[52] while the Bolsheviks did proclaim the partitions null and void.[53] Piłsudski thus speculated that Poland will be better of with the Bolsheviks, alienated from the Western powers, than with restored Russian Empire.[51][54] As such, by his refusal to join the attack on Lenin's struggling Soviet government, ignoring strong pressure from the Entente Cordiale, Piłsudski had likely saved the Bolshevik government in summer-fall 1919.[55]

In the aftermath of Russian westward offensive of 1918-1919 and a series of escalating battles, which resulted in Poles advancing east, in April 1920, Marshal Piłsudski (as his rank had been since that March) signed an alliance with Ukraine's leader, Symon Petliura, to conduct joint operations against Soviet Russia. The goal of the Polish-Ukrainian treaty, signed April 21, was to establish an independent Ukraine in alliance with Poland. In return, Petliura gave up Ukrainian claims to East Galicia, and was denounced for this by East Galician Ukrainian leaders.[33] The Polish and Ukrainian armies, under Piłsudski's command, launched a successful offensive against the Russian forces in Ukraine. On May 7, with remarkably little fighting, they captured Kiev.[56]

The Soviets launched their own successful counteroffensive from Belarus and counter-attacked in Ukraine, advancing into Poland[56] in a drive toward Germany in order to encourage the Communist Party of Germany, struggling to take power. Soviet confidence soared[57] The Soviets openly announced its plans for invading Western Europe, as Soviet communist theoretician Nicholas Bukharin, writing in Pravda, hoped for the resources to carry the campaign beyond Warsaw "straight to London and Paris".[58] General Mikhail Tukhachevsky's order of the day for July 2, 1920, read: "To the West! Over the corpse of White Poland lies the road to world-wide conflagration. March on Vilno, Minsk, Warsaw!"[59] and "onward to Berlin over the corpse of Poland!"[33]

On 1 July, in light of the advancing Soviet offensive, the Council for Defence of the Nation was formed. Chaired by Piłsudski, it was supposed to provide quick decision-making and temporarily replace the unruly Sejm.[60] However, the National Democrats argued that the string of Bolshevik victories was Piłsudski's fault,[61] demanded his resignation and some even accused him of treason, failing however to carry a vote of no confidence in the council on 19 July (this failure led to Dmowski's withdrawal from it).[62] Various factions, including the Entente, pressured Poland to surrender and enter into negotiations with the Bolsheviks; however, Piłsudski was a staunch advocate of continuing the fight.[62] On August 12 Piłsudski tendered his resignation to Prime Minister Wincenty Witos - agreeing to become the scapegoat if the military solution failed - but Witos refused to accept it.[62] Over the next few weeks, Poland's risky, unconventional strategy at the Battle of Warsaw (August 1920) managed to halt the Soviet advance.[56]

The Polish plan was developed by Piłsudski and others, including Tadeusz Rozwadowski.[63] Later some supporters of Piłsudski tried to portray him as the sole inventor of the Polish strategy, while his opponents would try to minimize his role.[64] In the West for a long time a myth persisted that it was French general Maxime Weygand of the French military mission to Poland who had saved Poland; modern scholars however agree that Weygand's role was minimal at best.[33][65][64]

Piłsudski's plan called for Polish forces to withdraw across the Vistula River and defend the bridgeheads at Warsaw and the Wieprz River, while some 25% of available divisions concentrated to the south for a strategic counter-offensive. Next the plan required that two armies under General Józef Haller facing Soviet frontal attack on Warsaw from the east, hold their entrenched positions at all costs. At the same time, an army under General Władysław Sikorski was to strike north from behind Warsaw, thus cutting off the Soviet forces attempting to envelope Warsaw from that direction. The most important role, however, was assigned to a relatively small (approximately 20,000-man), newly assembled "Reserve Army" (known also as the "Strike Group" — Grupa Uderzeniowa), commanded personally by Piłsudski, comprising the most determined, battle-hardened Polish units. Their task was to spearhead a lightning northern offensive, from the Vistula-Wieprz River triangle south of Warsaw, through a weak spot identified by Polish intelligence between the Soviet Western and Southwestern Fronts. That offensive would separate the Soviet Western Front from its reserves and disorganize its movements. Eventually, the gap between Sikorski's army and the "Strike Group" would close near the East Prussian border, resulting in the destruction of the encircled Soviet forces.[66][67]

At the time, Piłsudski's plan was strongly criticized, and only the desperate situation of the Polish forces persuaded other army commanders to go along with it. Although based on reliable intelligence, including decrypted Soviet radio communications, the plan was termed "amateurish" by many high-ranking army officers and military experts, who were quick to point out Piłsudski's lack of a formal military education. When a copy of the plan accidentally fell into Soviet hands, Tukhachevsky thought it a ruse and disregarded it.[56] Days later, the Soviets paid dearly for their mistake, when during the Battle of Warsaw the overconfident Red Army suffered one of its greatest defeats ever.[56][67]

A National Democrat Sejm deputy, Stanisław Stroński, coined the phrase, "Miracle at the Wisła" ("Cud nad Wisłą"),[68] to express his disapproval of Piłsudski's "Ukrainian adventure." Stroński's phrase was adopted as praise for Piłsudski by some patriotically- or piously-minded Poles who were unaware of Stroński's ironic intent.

Later a junior member of the French mission, Charles de Gaulle, would adopt some lessons from the war as well as from Piłsudski's career.[69][67]

In February 1921 Piłsudski visited Paris, where in negotiations with French president Alexandre Millerand he created the basis for the Franco-Polish Military Alliance, signed later this year.[70] The Treaty of Riga (March 1921), closing the Polish-Soviet War (Piłsudski called the treaty an "act of cowardice"),[71] partitioned Belarus and Ukraine between Poland and Russia. The treaty, and General Lucjan Żeligowski's capture of Wilno from the Lithuanians, marked an end to Piłsudski's federalist dream.[9] This became painfully clear on 25 September 1921, when Piłsudski visited Lwów for an opening ceremony for the Eastern Trade Fair (Targi Wschodnie), and was the target of an unsuccessful assassination attempt by Stefan Fedak, member of the Ukrainian Military Organization.[72]

Retirement and coup

After the Polish Constitution of March 1921 severely limited the powers of the presidency under the Second Polish Republic, Piłsudski refused to run for president.[9] On December 9, 1922, the National Assembly of Poland elected Gabriel Narutowicz of PSL Wyzwolenie; his election was opposed by the right-wing parties and caused increasing unrest.[73] On December 13, in Belweder palace, Piłsudski officially transferred his power as the Chief of State to Narutowicz; Naczelnik was replaced by the President.[74]

On December 16, after his inauguration, Narutowicz was shot dead by a mentally deranged, right-wing, anti-Semitic painter and art critic, Eligiusz Niewiadomski, who had originally wanted to kill Piłsudski, but changed his target when another non-right wing president has been elected.[75] For Piłsudski, this was a major shock; an event that significantly underminded his belief that Poland can function as a democracy.[76] According to the historian Norman Davies, Piłsudski believed in the rule of strong hand.[77] Piłsudski became the Chief of the General Staff and together with Władysław Sikorski, Polish Minister of Military Affairs, managed to stabilize the situation, quelling unrest with a short state of emergency.[78] Stanisław Wojciechowski of PSL Piast was elected the new president, and Wincenty Witos, also of PSL Piast, became the Prime Minister, but the new government - in the aftermath of the Lanckorona Pact (alliance between central PSL Piast and right wing National Populist Union and Christian Democracy parties) - contained right-wing enemies of Piłsudski, people whom he held morally responsible for Narutowicz's death and whom he found it impossible to work with.[79] On 30 May 1923 Piłsudski resigned as Chief of the General Staff; after general Stanisław Szeptycki proposed that military should be more closely supervised by civilian control, Piłsudski criticized that as an attempt to politicize the army and on 28 June he resigned from his last political appointment; on the same day the left-wing parties passed a declaration in Sejm thanking him for his past work.[80] Piłsudski went into retirement in Sulejówek, outside Warsaw, at his modest country house (which had been presented to him by his former soldiers), where he settled down to supporting his family by writing a series of political and military memoirs, including Rok 1920 (The Year 1920).[3]

Meanwhile Poland's economy was in shambles. Hyperinflation fueled public unrest, and the government was unable to find a quick solution to the mounting unemployment and economic crisis.[81] Piłsudski's allies and supporters repeatedly asked him to return to politics, and he began to create a new power base, centered around former members of the Polish Legions and the Polish Military Organization as well as some left-wing and intelligentsia parties. In 1925, after several governments had resigned in short order and the political scene was becoming increasingly chaotic, Piłsudski became more and more critical of the government, eventually issuing statements demanding the resignation of the Witos cabinet.[3][9] When the unpopular Chjeno-Piast coalition, which Piłsudski had strongly criticized, formed a new government,[9] on May 12-14, 1926, Piłsudski returned to power in a coup d'état (the May Coup), supported by the Polish Socialist Party, PSL Wyzwolenie, Stronnictwo Chłopskie and even the Communist Party of Poland.[82] Piłsudski hoped for a bloodless coup, but the government refused to back down.[83] During the coup, 215 soldiers and 164 civilians had been killed, and over 900 persons had been wounded.[84] President Stanisław Wojciechowski and Prime Minister Witos stepped down. Piłsudski, however, did not accept the office of president, aware of its limited powers. Piłsudski's formal offices — apart from two terms as prime minister in 1926-28 and 1930 — were for the most part limited to those of minister of defence and inspector-general of the armed forces. He also held the offices of minister of military affairs and chairman of the council of war.[3]

Authoritarian rule

Piłsudski had no plans for any major reforms; he quickly distanced himself from the most radical of his left-wing supporters, declaring that his coup was to be a "revolution without revolutionary consequences".[9] His goals were to stabilize the country, reduce the influence of political parties which he blamed for corruption and inefficiency, and strengthen the army.[85][9]

Internal politics

In internal politics, Piłsudski's coup meant vast limitations of parliamentary government in Poland for the next 10 years, as Piłsudski's Sanacja government (1926-1939) — conducted at times by authoritarian means — directed at restoring "moral health" to public life. From 1928 Sanacja was represented by the Non-partisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government. Popular support and elegant rhetoric allowed Piłsudski to maintain his authoritarian powers, which could not be overruled by the president, who in any case had been nominated by Piłsudski, not by Sejm, the powers of which were curtailed in constitutional amendments introduced soon after the coup, on 2 August 1926.[3] From 1926 to 1930, Piłsudski used mostly propaganda tools to weaken the position and influence of the opposition leaders.[9] The culmination of his dictatorial and 'above the law' policies came in 1930 with the imprisonment and trial of certain political opponents before the Polish legislative election, 1930, and the establishment of the prison for political prisoners in Bereza Kartuska (today Biaroza)[9] where some prisoners were brutally mistreated.[86] After the 1930 victory of BBWR Piłsudski left most internal matters in the hands of his "colonels", himself concentrating on military and foreign affairs.[9]

One of the main goals for Piłsudski, who was becoming increasingly disillusioned with the democracy,[87] was to transform the parliamentary system into a presidential system - however he opposed the introduction of a totalitarian system.[9] The adoption of a new Polish constitution in April 1935, tailored by Piłsudski's supporters to his specifications — providing for a strong presidency — came too late for Piłsudski to seek that office; but the April Constitution would serve Poland up to the outbreak of World War II and would carry its Government in Exile through to the end of the war and beyond. Nonetheless Piłsudski's reign depended more on his charismatic authority than on rational-legal authority.[9] None of his followers could claim to be his successor and after his death the Sanacja would quickly fracture, with Poland returning to the pre-Piłsudski era of parliamentary political struggles.[9]

Piłsudski's regime marked the much needed stabilization and improvements in the situation of ethnic minorities, which formed almost a third of the population of the Second Republic. Piłsudski replaced the National Democrats' "ethnic assimilation" with a "state assimilation" policy: citizens were judged by their loyalty to the state, not by their nationality.[88] The years 1926-1935, and Piłsudski himself, were favourably viewed by many Polish Jews, whose situation improved especially under the cabinet of the Piłsudski-appointed prime minister Kazimierz Bartel.[89][90] However a combination of various reasons, from the Great Depression[88] to the vicious spiral of terrorist attacks by Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and government pacifications meant that the situations of minorities of Poland was less than satisfactory, despite Piłsudski's efforts.[88][91]

In the military realm, Piłsudski, once a great military strategist responsible for the Miracle at Vistula, had been criticized by some for concentrating on personnel management, and ignoring development of new plans, strategies or military equipment.[9][92] His experiences from the Polish-Soviet War also meant that he overestimated the importance of cavalry, and he neglected the development of armored forces or a strong air force,[92] although others argue that particulary since late 1920s he supported the development of armor and airforce.[93]

Foreign policy

Under Piłsudski's direction, Poland had good foreign relations with some of its neighbors, notably Romania, Hungary and Latvia. However, relations with Czechoslovakia were strained, and with Lithuania — worse. Relations with Germany and the Soviet Union varied over time, but during Piłsudski's tenure could for the most part be described as neutral.[94][95][96]

Piłsudski, as de Gaulle was later to do in France, sought to maintain his country's independence on the international scene. Assisted by his protégé, Minister of Foreign Affairs Józef Beck, he sought support for Poland in alliances with western powers — France and Britain — and with friendly, if less powerful, neighbors: Romania and Hungary.[96] A supporter of the Franco-Polish Military Alliance and the Polish-Romanian Alliance (part of the Little Entente), he was disappointed by the French and British policy of appeasement evident in those countries' signing of the Locarno Treaties.[95][97][98] Piłsudski therefore aimed to also maintain good relations with the USSR and Germany; hence Poland signed non-aggression pacts with both its powerful neighbors (the 1932 Soviet-Polish Non-Aggression Pact, and the 1934 German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact).[96] The two treaties were meant to strengthen Poland's position in the eyes of its allies and neighbors.[3] Piłsudski himself was acutely aware of the shakiness of the non-aggression pacts, and remarked: "Having these pacts, we are straddling two stools. This cannot last long. We have to know from which stool we will tumble first and when that will be."[99]

Piłsudski's Promethean program, designed to weaken Tsarist Russia and its successor the Soviet Union by supporting nationalist independence movements of major non-Russian peoples dwelling within Russia or the Soviet Union, was coordinated from 1927 to the 1939 outbreak of World War II in Europe by the military intelligence officer Edmund Charaszkiewicz. The Prometheist movement, however, yielded few tangible results in this period.[100]

There is some controversy about Piłsudski's rumored proposal to France on declaring war on Germany after Hitler had come to power in January 1933. Some historians argue that Piłsudski may have sounded out France regarding the possibility of joint military action against Germany, which had been openly rearming in violation of the Versailles Treaty.[101] French refusal might have been one of the reasons Poland signed the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact in January 1934.[102][103][96][104] However, this has been disputed by historians who point out that there is little evidence in either the French or Polish diplomatic archives that such a proposal was ever advanced.[105]

Hitler unceasingly proposed a German-Polish alliance against the Soviets, but Piłsudski declined, instead seeking precious time to prepare for war with Germany or the Soviet Union if need be.[104][106] Hitler also on numerous occasions hoped to meet with Piłsudski, and again was rebuffed.[104] Just before his death Piłsudski told Beck that Poland's policy must be to maintain neutral relations with Germany, alliance with France and improve the relations with United Kingdom.[96]

Death

("A mother and the heart of her son") and bears evocative lines from a poem by Słowacki.

By 1935, unbeknownst to the public, Piłsudski had for several years been in declining health. On May 12, 1935, he died of liver cancer at Warsaw's Belweder Palace. His funeral turned into a national tribute to the man who had probably done more than any other to restore Poland's independence.

Piłsudski's body was laid to rest in St. Leonard's Crypt at Kraków's Wawel Cathedral, except for his brain, which was donated to science, and his heart, which was interred in his mother's grave at Vilnius' Rossa Cemetery, where it remains.[3]

Legacy

I am not going to dictate to you what you write about my life and work. I only ask that you not make me out to be a "whiner and sentimentalist." — Piłsudski, 1908.[107]

On May 13, 1935, in accordance with Józef Piłsudski's last wishes, Edward Rydz-Śmigły was named by Poland's president and government to be Inspector-General of the Polish Armed Forces, and on November 10, 1936, he was elevated to Marshal of Poland.[108] Rydz was now one of the most powerful people in Poland — the "second man in the state after the President."[109] While many saw Rydz-Śmigły as a successor to Piłsudski, he never became as influential.[110] The Polish government became increasingly authoritarian and conservative, with Rydz-Śmigły faction opposed by that of the more moderate Ignacy Mościcki, who remained President.[110] After 1938 Rydz-Śmigły reconciled with the President, but the ruling group remained divided into the "President's Men," mostly civilians (the "Castle Group," after the President's official residence, Warsaw's Royal Castle), and the "Marshal's Men" ("Piłsudski's Colonels"), professional military officers and old comrades-in-arms of Piłsudski's. After the German invasion of Poland in 1939, some of this political division survived within the Polish government in exile.

Piłsudski had given Poland something akin to what Henryk Sienkiewicz's Onufry Zagłoba had mused about: a Polish Oliver Cromwell. As such, the Marshal had inevitably drawn both intense loyalty and intense vilification.[102][111]

After World War II, little of Piłsudski's thought influenced the policies of the Polish People's Republic, a de facto satellite of the Soviet Union. Piłsudski was either ignored or condemned by the communist government, together with the entire period of the Second Polish Republic. Nonetheless this changed with time, particularly after destalinization and the Polish October, and evolving Polish historiography moved away from a purely negative view of him towards a more balanced and neutral study.[112]

After the fall of communism, Piłsudski came to be publicly acknowledged as a national hero.[2] On the sixtieth anniversary of his death, on May 12, 1995, Poland's Sejm issued a statement: "Józef Piłsudski will remain, in our nation's memory, the founder of its independence and the victorious leader who fended off a foreign assault that threatened the whole of Europe and its civilization. Józef Piłsudski served his country well and has entered our history forever."[113]

This declaration was consonant with President Mościcki's words at Piłsudski's 1935 funeral: "He was the king of our hearts and the sovereign of our will. During a half-century of his life’s travails, he captured heart after heart, soul after soul, until he had drawn the whole of Poland within the purple of his royal spirit... He gave Poland freedom, boundaries, power and respect."[114]

After World War I, about the time of the Polish-Soviet War (1919-21), Joseph Conrad had said of Piłsudski: "He was the only great man to emerge on the scene during the war World War I." Conrad had added, "In some aspects he is not unlike Napoleon, but as a type of man he is superior. Because Napoleon, his genius apart, was like all other people and Piłsudski is different."[115]

One of Poland's most brilliant 20th-century military commanders, Piłsudski has lent his name to several military units, including the 1st Legions Infantry Division and armored train Nr. 51 ("I Marszałek").[116]

Also named for him have been Piłsudski's Mound, one of the four man-made mounds at Kraków;[117] the Józef Piłsudski Institute of America, a New York research center and museum on the modern history of Poland;[118] the Warsaw Academy of Physical Education;[119] a passenger ship, MS Piłsudski; a gunboat, ORP Komendant Piłsudski; and a racehorse, Pilsudski.

Józef Piłsudski's life was the subject of a 2001 Polish television program, Marszałek Piłsudski, directed by Andrzej Trzos-Rastawiecki.[120]

Names

As a young man, Piłsudski belonged to various underground organizations and used a variety of pseudonyms, including "Wiktor," "Mieczysław" and "Ziuk." Later he was often affectionately called "Dziadek" ("Grandpa" or "the Old Man") and "Marszałek" ("the Marshal"). His ex-soldiers also referred to him as "Komendant" ("the Commandant").

Relatives

Józef Piłsudski's notable relatives included his brothers: Adam Piłsudski, a politician; Bronisław Piłsudski, a noted ethnographer; Jan Piłsudski, a lawyer and politician; and daughter Wanda Piłsudska, who remained in Britain after World War II, working as a psychiatrist.

See also

Notes

a. ^ The question of Piłsudski's ethnicity and culture is one with no easy answers. Timothy Snyder, who calls him a "Polish-Lithuanian", notes that Piłsudski did not think in the terms of 20th century nationalisms and ethnicities; he considered himself both a Pole and a Lithuanian and his homeland was the historical Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[121] For information on Piłsudski's family, see Piłsudski (family).

b. ^ Zbigniew Brzezinski in his introduction to Wacław Jędrzejewicz’s Pilsudski A Life For Poland wrote: Some years before his death Pilsudski, in a statement which epitomises the essence of modern Polish history, stated: “To be defeated and not yield is victory. To win and to rest on laurels is defeat”. ... Pilsudski’s vision of Poland, paradoxically, was never attained. He contributed immensely to the creation of a modern Polish state, to the preservation of Poland from the Soviet invasion, yet he failed to create the kind of multinational commonwealth, based on principles of social justice and ethnic tolerance, to which he aspired in his youth. One may wonder how relevant was his image of such a Poland in the age of nationalism...[122]

References

- ^ Plach, Eva (2006). The Clash of Moral Nations: Cultural Politics in Pilsudski's Poland, 1926-1935. Ohio, United States: Ohio University Press. p. 14. 0821416952.

- ^ a b Aviel Roshwald, Richard Stites, European Culture in the Great War: The Arts, Entertainment and Propaganda, 1914-1918, Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0521013240, Google Books, p.60

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Józef Piłsudski (1867 - 1935)". Poland.gov.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:Pl icon Bohdan Urbankowski, Józef Piłsudski: marzyciel i strateg (Józef Piłsudski: Dreamer and Strategist), tom pierwszy (volume one), Warsaw, Wydawnictwo ALFA, 1997, ISBN 8370019145, pp. 13-15.

- ^ Jerzy Jan Lerski, Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945, Greenwood Press, 1996, ISBN 0313260079, Google Print, p.449

- ^ Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries. "A History of Eastern Europe Crisis and Change".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Roshwald, Aviel (2001). Ethnic Nationalism and the Fall of Empires: Central Europe, the Middle East and Russia, 1914-1923. Routledge. pp. p. 36. ISBN 0415242290.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b MacMillan, Margaret, Paris 1919 : Six Months That Changed the World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2003, ISBN 0375760520, p. 208.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Piłsudski Józef Klemens by Andrzej Chojnowski. Entry in Polish PWN Encyclopedia

- ^ "Pilsudski, Józef Klemens," Microsoft Encarta. Last accessed on 30 May 2006

- ^ a b Template:Pl icon Kalendarium wydarzeń życia Bronisława Piłsudskiego (Calendar of events in the life of Bronisław Piłsudski). Retrieved on 2 August 2007.

- ^ a b Urbankowski, op cit, p. 50

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit, p. 71

- ^ a b Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 62-66

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 68-69

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 74-77

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Page 88

- ^ a b c MacMillan, op. cit., p. 209.

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Page 93

- ^ Template:Pl icon Aleksandra Piłsudska, last accessed on 30 May 2006

- ^ a b c Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 109-111

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Adam Zamoyski (1987). The Polish Way. London: John Murray. p. 422. ISBN 0531150690.

p. 330

- ^ a b c d e f g h Zamoyski, op cit, p. 332.

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 113-116

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 117-118

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 131

- ^ a b Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 121-122

- ^ Hans Roos, A History of Modern Poland, from the Foundation of the State in the First World War to the Present Day, Alfred A. Knopf, 1966., p. 14. Translated from the German (Geschichte der polnischen Nation, 1916-1960) by J.R. Foster.

- ^ a b c d Zamoyski, op cit, p. 333.

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 171-172

- ^ Template:Pl icon Przemówienie do I kompanii kadrowej, Kraków, Oleandry, 3 sierpnia 1914. Polityka, 26 September2006

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 168

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m THE REBIRTH OF POLAND University of Kansas, lecture notes by professor Anna M. Cienciala, 2004. Last accessed on 2 June 2006.

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 174-175

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 178-179

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 170-171 and 180-182

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 251-252

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 253

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 256 and 277-278

- ^ Włodzimierz Suleja, Józef Piłsudski, Wrocław, 2004, ISBN 8304047063, p.202

- ^ a b c d e f MacMillan, op cit, p. 210.

- ^ MacMillan, op cit, pp. 213-214.

- ^ MacMillan, op cit, p. 211 and p.214.

- ^ Manfred F. Boemeke, Gerald D. Feldman, Elisabeth Glaser, The Treaty of Versailles: A Reassessment After 75 Years, Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 0521621321, Google Books, p.314

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 499-501

- ^ Polish-Soviet War: Battle of Warsaw. Accessed October 10, 2007.

- ^ George Sanford, Democratic Government in Poland: Constitutional Politics Since 1989. Palgrave Macmillan 2002. ISBN 0-333-77475-2. Google Print, pp. 5-6 [1]

- ^ MacMillan, op cit, p. 211

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 281

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., page 90 (second tome)

- ^ a b Peter Kenez, A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to the End, Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 0521311985, Google Books, p.37

- ^ Template:Pl icon Bohdan Urbankowski, Józef Piłsudski: marzyciel i strateg, (Józef Piłsudski: Dreamer and Strategist), Tom drugi (second volume), Wydawnictwo ALFA, Warsaw, 1997, ISBN 8370019145, p. 83

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 291

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., page 45 (second tome)

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., page 92 (second tome)

- ^ a b c d e Davies, Norman, White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919-20, Pimlico, 2003, ISBN 0712606947. (First edition: New York, St. Martin's Press, inc., 1972.)

- ^ See Lenin's speech, English translation quoted from Richard Pipes, RUSSIA UNDER THE BOLSHEVIK REGIME, New York, 1993, pp.181-182, with some stylistic modification in par 3, line 3, by A. M. Cienciala. This document was first published in a Russian historical periodical, Istoricheskii Arkhiv, vol. I, no. 1., Moscow,1992 and is cited through THE REBIRTH OF POLAND. University of Kansas, lecture notes by professor Anna M. Cienciala, 2004. Last accessed on 2 June 2006.

- ^ Stephen F. Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography, 1888-1938, Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0195026977, Google Books, p. 101

- ^ Battle Of Warsaw 1920 by Witold Lawrynowicz; A detailed write-up, with bibliography. Last accessed on 5 November 2006.

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 341-346 and 357-358

- ^ Suleja, op.cit., p. 265

- ^ a b c Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 341-346

- ^ John Erickson, The Soviet High Command: A Military-Political History, 1918-1941, Routledge, ISBN 0714651788 Google Books, p.95

- ^ a b Conceptions of National History: Proceedings of Nobel Symposium 78, Walter de Gruyter, 1994, ISBN 3110135043 Google Books, p.230

- ^ Template:Pl icon Janusz Szczepański, KONTROWERSJE WOKÓŁ BITWY WARSZAWSKIEJ 1920 ROKU (Controversies surrounding the Battle of Warsaw in 1920). Mówią Wieki, online version.

- ^ Janusz Cisek, Kosciuszko, We Are Here: American Pilots of the Kosciuszko Squadron in Defense of Poland, 1919-1921, McFarland & Company, 2002, ISBN 0786412402, Google Books, p.140-141

- ^ a b c Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 346-441 and 357-358

- ^ Template:Pl icon Głos, 32/2005, Cud nad Wisłą. Last accessed on 18 June 2006.

- ^ Norman Davies, Europe: A History, HarperCollins, 1998, ISBN 0060974680, Google Books, p.935

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Page 484

- ^ Norman Davies, God's Playground. Vol. 2: 1795 to the Present. Columbia University Press. 1982. ISBN 0231053525. Google Books, p.399)

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Page 485

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 487-488

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 488

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 489

- ^ Suleja, op.cit., p.300

- ^ Norman Davies. 1984: Heart of Europe: A Short History of Poland. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-285152-7. Page 140: "Pilsudski believed that the world was ruled by brute force, and that fundamental changes could only be obtained, or essential interests defended, by the willingness to use violence, terror, and military power."

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 489-490

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 490-491

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 490

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 502

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 515

- ^ Suleja, op.cit., p. 343

- ^ Template:Pl icon Wojciech Roszkowski Historia Polski 1914-1991, Warszawa, 1992 ISBN 83-01-11014-7, pg 53 section 5.1

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 528-529

- ^ Template:Pl icon Wojciech Śleszyński, Aspekty prawne utworzenia obozu odosobnienia w Berezie Kartuskiej i reakcje środowisk politycznych. Wybór materiałów i dokumentów 1, published in Беларускі Гістарычны Зборнік nr 20 (Belarusian history journal)

- ^ Yohanan Cohen, Small Nations in Times of Crisis and Confrontation, SUNY Press, 1989, ISBN 0791400182 Google Books, p.65

- ^ a b c Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999, Yale University Press, ISBN 030010586XGoogle Books, p.144

- ^ Feigue Cieplinski, Poles and Jews: The Quest For Self-Determination 1919-1934, Binghamton Journal of History, Fall 2002, Last accessed on 2 June 2006.

- ^ Paulsson, Gunnar S., Secret City: The Hidden Jews of Warsaw, 1940-1945, Yale University Press, 2003, ISBN 0300095465, Google Books, p. 37

- ^ Davies, God's Playground, op.cit., Google Print, p.407

- ^ a b Andrzej Garlicki, Jozef Pilsudski. 1867-1935. Scolar Press, 1995, ISBN. 1859280188, p.178

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., vol.2, p. 30-337

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 538

- ^ a b Ilya Prizel, National Identity and Foreign Policy: Nationalism and Leadership in Poland, Russia and Ukraine, Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 0521576970, Google Books, p.71

- ^ a b c d e Urbankowski, op.cit., Pages 539-540

- ^ John Lukacs, The Last European War: September 1939-December 1941, Yale University Press, 2001, ISBN 0300089155 Google Books, p.30

- ^ Nicole Jordan, The Popular Front and Central Europe: The Dilemmas of French Impotence 1918-1940, Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0521522420, Google Books, p.23

- ^ Kipp, Jacob, ed., Central European Security Concerns: Bridge, Buffer, Or Barrier?, Routledge, 1993, ISBN 0714645451, Google Books, p. 95

- ^ Template:Pl icon Edmund Charaszkiewicz, Zbiór dokumentów ppłk. Edmunda Charaszkiewicza, opracowanie, wstęp i przypisy (A Collection of Documents by Lt. Col. Edmund Charaszkiewicz, edited, with introduction and notes by) Andrzej Grzywacz, Marcin Kwiecień, Grzegorz Mazur (Biblioteka Centrum Dokumentacji Czynu Niepodległościowego, tom vol. 9), Kraków, Księgarnia Akademicka, 2000, ISBN 83-7188-449-4, pp. 56-87 et passim.

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., vol.2, p. 317-326

- ^ a b Tomasz Torbus, Nelles Guide Poland, Hunter Publishing, Inc, 1999, ISBN 3886180883 Google Books, p.25

- ^ George H. Quester, Nuclear Monopoly, Transaction Publishers, 2000, ISBN 0765800225, Google Books, p.27. Note that author gives a source: Richard M. Watt, Bitter Glory, Simon and Schuster, 1979

- ^ a b c Kazimierz Maciej Smogorzewski. "Józef Piłsudski". Encyclopædia Britannica.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessdaymonth=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:Pl icon Dariusz Baliszewski, Ostatnia wojna marszałka, Tygodnik "Wprost", Nr 1148 (28 November 2004), Polish, retrieved on 24 March 2005

- ^ Klaus Hildebrand, The Foreign Policy of the Third Reich, University of California Press, 1973, ISBN 0520025288 Google Books, p.33

- ^ Urbankowski, op.cit., p. 133-41.

- ^ Marek Jabłonowski, Piotr Stawecki, Następca komendanta. Edward Śmigły-Rydz. Materiały do biografii. Wyższa Szkoła Humanistyczna w Pułtusku. 1998. ISBN 9390920808, p.13

- ^ Następca..., op.cit., p.5

- ^ a b Następca..., op.cit., p.14

- ^ Jeffrey C. Goldfarb, Beyond Glasnost: The Post-Totalitarian Mind, University of Chicago Press, 1992, ISBN 0226300986, Google Books, p.152

- ^ Władysław Władyka, Z Drugą Rzeczpospolitą na plecach. Postać Józefa Piłsudskiego w prasie i propagandzie PRL do 1980 roku. in Marek Jabłonowski, Elżbieta Kossewska (ed.), Piłsudski na łamach i w opiniach prasy polskiej 1918-1989. Oficyna Wydawnicza ASPRA-JR and Warsaw University. 2005. ISBN 8389964449. p.285-311. and Małgorzata and Mariusz Żuławnik, Powrót na łamy. Józef Piłsudski w prasie oficjalnej i podziemnej 1980-1989., ibid.

- ^ Translation of OŚWIADCZENIE SEJMU RZECZYPOSPOLITEJ POLSKIEJ z dnia 12 maja 1995 r. w sprawie uczczenia 60 rocznicy śmierci Marszałka Józefa Piłsudskiego. (M.P. z dnia 24 maja 1995 r.). For Polish original online, see here.

- ^ Translation of Mościcki's speech from 1935. For Polish original online, see Piotr M. Kobos, SKAZUJĘ WAS NA WIELKOŚĆ: Legenda Józefa Piłsudskiego, Nr 2 (43), September 2005.

- ^ Zdzisław Najder, Conrad under Familial Eyes, Cambridge University Press, 1984, ISBN 052125082X, p. 239.

- ^ Polish Armoured Train Nr. 51 ("I Marszałek"). PIBWL. Last accessed on 30 May 2006.

- ^ Template:Pl icon Kopiec Józefa Piłsudskiego on the pages of Pedagogical University of Cracow. Retrieved on 18 September 2007.

- ^ Welcome page at the 'Józef Piłsudski Institute of America', last accessed on 26 May 2006.

- ^ Józef Piłsudski Academy of Physical Education in Warsaw. Site of the Polish Ministry of Education. Last accessed on 30 May 2006.

- ^ "Marszalek Pilsudski" (2001) (mini). IMDb. Last accessed on 30 May 2006.

- ^ Timothy Snyder. "The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Wacław Jędrzejewicz, Pilsudski A Life For Poland, Hippocrene Books Inc., 1991, ISBN 0870527479

Further reading

- Please note this is only a small selection. National Library in Warsaw, for example, lists over 500 publications related to Piłsudski.

- Template:Pl icon Czubiński, Antoni (ed.), Józef Piłsudski i jego legenda, Państowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1988, ISBN 8301078197

- Davies, Norman, Heart of Europe, the Past in Poland's Present, Oxford University Press, 1984, 2001, ISBN 0192801260

- Dziewanowski, M. K., Joseph Pilsudski: A European Federalist, 1918-1922, Stanford, CA, 1969, ISBN 817917918

- Template:Pl icon Garlicki, Andrzej, Jozef Pilsudski, 1867-1935, Scolar Press, 1995 (Polish edition, 1990), ISBN 1859280188

- Hauser, Przemysław, "Jozef Pilsudski's Views on the Territorial Shape of the Polish State and His Endeavours to Put them into Effect, 1918-1921," Polish Western Affairs, Poznan, 1992, no. 2, pp. (235)-249, trans. Janina Dorosz

- Jędrzejewicz, Wacław, Pilsudski: a Life for Poland, Hippocrene Books, 1982, ISBN 0882546333

- Template:Pl icon Jędrzejewicz, Wacław, Józef Piłsudski 1867–1935, Wrocław 1989; ISBN 8388736256

- Template:Ru iconTemplate:Uk icon Pidlutskyi, Oleksa, Postati XX stolittia, (Figures of the 20th century), Kiev, 2004, ISBN 9668290011, LCCN 20-0. Chapter "Józef Piłsudski: The Chief who Created Himself a State" reprinted in Zerkalo Nedeli (the Mirror Weekly), Kiev, February 3-9 February, 2001, in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- Piłsudska, Aleksandra, Pilsudski: A Biography by His Wife, Dodd, Mead and Co. NY., 1941

- Piłsudski, Józef, Darsie Rutherford Gillie, Joseph Pilsudski, the Memories of a Polish Revolutionary and Soldier, Faber & Faber, 1931

- Jozef Pilsudski, Year 1920 and its Climax: Battle of Warsaw during the Polish-Soviet War, 1919-1920, with the Addition of Soviet Marshal Tukhachevski's March beyond the Vistula, New York (Jozef Pilsudski Institute of America), 1972, ISBN B0006EIT3A

- Template:Pl icon Polski Słownik Biograficzny (Polish Biographical Dictionary), Zeszyt 109 (T. XXVI/2), pp. 311-324

- Reddaway, W. F., Marshal Pilsudski, Routledge, 1939

- Rothschild, Joseph, Pilsudski's Coup d'Etat, Columbia University Press, 1967, ISBN 0231029845

- Wandycz, Piotr S., "Polish Federalism 1919-1920 and its Historical Antecedents," East European Quarterly, Boulder, CO., 1970, vol. IV, no. 1, pp. 25-39.

- Template:Pl icon Wójcik, Włodzimierz, Legenda Piłsudskiego w Polskiej literaturze międzywojennej (Piłsudski's Legend in Polish interwar literature), Warszawa, 1987, ISBN 8321605338

External links

- Marshal Jozef Pilsudski. Messiah and Central European Federalist by Patryk Dole

- Template:En icon/Template:Pl icon Jozef Pilsudski Institute of America

- Template:En icon Józef Piłsudski his life and times. Website by Mike Oborski, Honorary Consul of Poland in Kidderminster (West Midlands of the United Kingdom)

- Template:En icon Abbreviated version of biography from the above page. Site by Roman Solecki.

- Template:En icon Josef Piłsudski's biographical sketch

- Template:Pl icon Bibuła, book by Józef Piłsudski

- Template:Pl icon Historical media Recording of short speech by Piłsudski from 1924