Rajneesh: Difference between revisions

15 em ref cols |

Restored biographical film content per consensus seen at film article AFD -- please do NOT sneakily violate it and phase it out entirely |

||

| Line 210: | Line 210: | ||

In Rajneeshpuram, Osho dictated three books while undergoing dental treatment under the influence of [[nitrous oxide]] (laughing gas): ''Glimpses of a Golden Childhood'', ''Notes of a Madman'', and ''Books I Have Loved''.<ref>{{harvnb|Shunyo|1993|p=74}}</ref> Subsequently, there were allegations that Osho had been addicted to nitrous oxide gas.<ref name="JMF48">{{harvnb|Fox|2002|p=48}}</ref><ref name=Storr59>{{harvnb|Storr|1996|p=59}}</ref> In addition, Sheela claimed in a 1985 interview on the American CBS television show ''[[60 Minutes]]'' that Osho took sixty milligrams of [[Valium]] every day.<ref name=Storr59 /><ref>[http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_product=CO&s_site=charlotte&p_multi=CO&p_theme=realcities&p_action=search&p_maxdocs=200&p_topdoc=1&p_text_direct-0=0EB6BFB58F61E687&p_field_direct-0=document_id&p_perpage=10&p_sort=YMD_date:D&s_trackval=GooglePM Charlotte Observer article dated 4 November 1985]</ref> When questioned by journalists about the allegations of daily Valium and nitrous oxide use, Osho categorically denied both, describing the allegations as "absolute lies".<ref>Osho: ''The Last Testament'', Vol. 4, Chapter 19 (transcript of an interview with German magazine, ''[[Der Spiegel]]'')</ref> |

In Rajneeshpuram, Osho dictated three books while undergoing dental treatment under the influence of [[nitrous oxide]] (laughing gas): ''Glimpses of a Golden Childhood'', ''Notes of a Madman'', and ''Books I Have Loved''.<ref>{{harvnb|Shunyo|1993|p=74}}</ref> Subsequently, there were allegations that Osho had been addicted to nitrous oxide gas.<ref name="JMF48">{{harvnb|Fox|2002|p=48}}</ref><ref name=Storr59>{{harvnb|Storr|1996|p=59}}</ref> In addition, Sheela claimed in a 1985 interview on the American CBS television show ''[[60 Minutes]]'' that Osho took sixty milligrams of [[Valium]] every day.<ref name=Storr59 /><ref>[http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_product=CO&s_site=charlotte&p_multi=CO&p_theme=realcities&p_action=search&p_maxdocs=200&p_topdoc=1&p_text_direct-0=0EB6BFB58F61E687&p_field_direct-0=document_id&p_perpage=10&p_sort=YMD_date:D&s_trackval=GooglePM Charlotte Observer article dated 4 November 1985]</ref> When questioned by journalists about the allegations of daily Valium and nitrous oxide use, Osho categorically denied both, describing the allegations as "absolute lies".<ref>Osho: ''The Last Testament'', Vol. 4, Chapter 19 (transcript of an interview with German magazine, ''[[Der Spiegel]]'')</ref> |

||

=== Planned biographical film === |

|||

'''''Guru of Sex''''' has been a planned [[live action]] [[English (language)|English language]] film about [[Osho]], also known as [[Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh]], written by [[Farrukh Dhondy]].<ref name="livemint">{{cite news | last =Staff | first = | coauthors = | title =Indian animation takes giant leap forward: With the industry expected to grow at 30% per annum, companies like CDI are going full throttle through overseas listing and projections of making four international films a year | work =livemint.com (Partner: [[The Wall Street Journal]]) | pages = | language = | publisher =Hindustan Times Media Limited | date =[[June 18]], [[2007]] | url =http://www.livemint.com/Articles/2007/06/18112804/Indian-animation-takes-giant-l.html | accessdate = 2007-12-17 }}</ref><ref name="vashisht">{{cite news | last =Vashisht | first =Dinker | coauthors = | title =Gandhi will return as Rajneesh, via Chandigarh: Chandigarh firm ropes in Ben Kingsley for its film, Guru of Sex | work =The Sunday Express | pages = | language = | publisher =Indian Express Newspapers (Mumbai) Ltd. | date =[[August 5]], [[2007]] | url =http://www.indianexpress.com/iep/sunday/story/208700.html | accessdate = 2007-12-17}}</ref> |

|||

=== Development === |

|||

Sir [[Ben Kingsley]] has been cast in the role of Osho.<ref name="bhushan">{{cite news | last =Bhushan | first =Nyay | coauthors = | title =Indian film firms go Alternative: Bollywood producer latest to raise cash via AIM IPO | work =[[Hollywood Reporter]] | pages = | language = | publisher =[[Nielsen Company|Nielsen Business Media, Inc.]] | date =[[June 19]], [[2007]] | url =http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/hr/content_display/film/news/e3ib6d2c95cdf6b2ef3dd40422b3743604e | accessdate = 2007-12-17 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news | last =Staff | first = | coauthors = | title =New Compact Disc Arm to List on London SE | work =[[Business Line]] | pages = | language = | publisher =Kasturi & Sons Ltd | date =[[June 16]], [[2007]] | url = | accessdate = }}</ref> The film is being written by MediaOne Ventures Ltd., which is a division of [[Chandigarh]], [[India|India-based]] Compact Disc India Limited (CDI).<ref name="vashisht" /> The film has a projected budget of [[USD|USD$]]16 million, and will be shot in [[Vietnam]], [[Laos]] and [[Cambodia]], because the locations resemble the current Osho centre in [[Pune]].<ref name="mehta" /><ref>{{cite news | last =Staff | first = | coauthors = | title =Compact Disc to float subsidiary in UK | work =The Economic Times | pages = | language = | publisher =Times Internet Limited | date =[[June 13]], [[2007]] | url =http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/News/News_By_Industry/Infotech/Software/Compact_Disc_to_float_subsidiary_in_UK/articleshow/2119332.cms | accessdate = 2007-12-17 }}</ref><ref name="vashisht" /> CDI has also signed a $20.15 million deal with the [[Los Angeles]] based company Motion Pixel Corporation to co-produce an animated soccer film called ''Goaaal!''.<ref name="livemint" /><ref name="khanna">{{cite news | last =Khanna | first = Ruchika M. | coauthors = | title =Chandigarh firm to co-produce soccer flick | work = Tribune News Service | pages = | language = | publisher =The Tribune Trust, [[Chandigarh]], [[India]] | date =[[May 22]], [[2007]] | url =http://www.tribuneindia.com/2007/20070523/biz.htm | accessdate = 2007-12-17 }}</ref> Voice actors signed on to ''Goaaal!'' include Ben Kingsley, [[Catherine Zeta Jones]], [[Michael Douglas]] and [[Christina Aguilera]].<ref name="khanna" /> Though the deals for both ''Goaaal!'' and ''Guru of Sex'' were signed by CDI, production will be handled by MediaOne Ventures.<ref name="livemint" /> The combined sales revenue of both films is projected at over $200 million.<ref name="livemint" /> |

|||

=== Response from Osho centres === |

|||

Both the Osho Commune International in Pune and the Osho World Foundation in [[Delhi]] have not had favorable responses to news of the film.<ref name="mehta">{{cite news | last =Mehta | first =Sunanda | coauthors = | title =Osho centres disown Guru of Sex movie: Preacher will be called Rajneesh to avoid legal wrangles, climax more controversial, says film company | work =PUNE Newsline | pages = | language = | publisher =Indian Express Newspapers (Mumbai) Ltd. | date =[[August 11]], [[2007]] | url =http://cities.expressindia.com/fullstory.php?newsid=250328 | accessdate = 2007-12-17 }}</ref> Swami Chaitanya Keerti, editor of ''Osho World Magazine'', stated "With such a title, it’s no mystery what kind of film it’s going to be," and said that the Osho centres will not cooperate with the film's production.<ref name="mehta" /> "We haven’t been contacted for any information, photographs or research for this film," said Ma Sadhana, a member of the Pune commune.<ref name="mehta" /> CDI chairman Suresh Kumar said that he contacted both of the Osho centres, but they refused to provide any help.<ref name="mehta" /> "We have called him a ‘guru of sex’ and obviously this is not how they would want him portrayed," said Kumar.<ref name="mehta" /> |

|||

=== Contents === |

|||

The film is inspired by the life of Osho, and "will have a controversial theme of depicting the ‘not so sacred’ acts inside a holy cult."<ref>{{cite news | last =Staff | first = | coauthors = | title =CDI’s MediaOne Venture to float on AIM, UK | work =Moneycontrol India | pages = | language = | publisher =e-Eighteen.com Ltd | date =[[June 14]], [[2007]] | url =http://www.moneycontrol.com/india/news/OTHER%20NEWS/cdi%E2%80%99s-mediaone-venture-to-floataim-uk/00/48/286696 | accessdate = 2007-12-17 }}</ref> The production company is taking steps to avoid legal controversies, and will refer to the main character as "Rajneesh" instead of "Osho", because Rajneesh is a more common name.<ref name="mehta" /> The film will chronicle Rajneesh's beginnings in [[Jabalpur]] and will follow his journey from India to the [[United States]].<ref name="mehta" /> A disclaimer at the beginning of the film will state that "any resemblance to person, dead or alive, is incidental."<ref name="mehta" /> According to Suresh Kumar, "The climax makes the startling revelation that the guru of sex in fact never enjoyed sex."<ref name="mehta" /> |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 22:53, 2 September 2008

Osho | |

|---|---|

| File:Osho.jpg Osho ("Rajneesh" Chandra Mohan Jain, रजनीश चन्द्र मोहन जैन) | |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Notable work | From Sex to Superconsciousness My Way, the Way of the White Clouds The Book of Secrets |

| Movement | Jivan Jagruti Andolan; Neo-sannyas |

"Rajneesh" Chandra Mohan Jain (Hindi: रजनीश चन्द्र मोहन जैन) (December 11, 1931 – January 19, 1990), also known as Acharya Rajneesh from the 1960s onwards, calling himself Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh during the 1970s and 1980s and taking the name Osho in 1989, was an Indian mystic and guru.

A professor of philosophy, he travelled throughout India in the 1960s as a public speaker, raising controversy by speaking against socialism, Mahatma Gandhi and institutionalised religion. He advocated a more open attitude towards sexuality, a stance that earned him the sobriquet "sex guru" in the Indian and later the international press. In 1970, he settled for a while in Mumbai (Bombay). He began initiating disciples (known as neo-sannyasins) and took on the role of a spiritual teacher. In his discourses, he reinterpreted writings of religious traditions, mystics and philosophers from around the world. Moving to Pune (Poona) in 1974, he established an Ashram that attracted increasing numbers of Westerners. The Ashram offered therapies derived from the Human Potential Movement to its Western audience and made news in India and abroad, chiefly because of its permissive climate and Osho's provocative lectures.

In 1981, Osho moved to the United States. His followers established an intentional community in Oregon, incorporated as the City of Rajneeshpuram. In this period, Osho attracted media attention for his large and ever-expanding collection of Rolls-Royce motorcars. Subject to intense hostility and coordinated pressures from many sections of the Oregon population, the Oregon commune collapsed in 1985, when Osho revealed that the commune leadership had committed a number of serious crimes, including a bioterror attack on the citizens of The Dalles. Shortly after, Osho himself was arrested and charged with immigration violations. He left the United States in accordance with a plea bargain. After a world tour during which twenty-one countries denied him entry, Osho returned to Pune, where he died in 1990. His Ashram is today known as the Osho International Meditation Resort.

Osho's syncretic teachings emphasise the importance of meditation, awareness, love, celebration, creativity and humour – qualities that in his view are suppressed by adherence to static belief systems, religious tradition and socialisation. His teachings have had a considerable impact on Western New Age thought;[1] in his home country, India, their popularity has increased markedly since his death.[2]

Biography

Early life

Osho was born Chandra Mohan Jain (Hindi: चन्द्र मोहन जैन) in Kuchwada,[3] a small village in the Narsinghpur District of Madhya Pradesh state in India, as the eldest of eleven children of a cloth merchant.[4] His parents, who were Taranpanthi Jains, sent him to live with his maternal grandparents until he was seven years old.[5] By Osho's own account,[6] this was a major influence on his development, because his grandmother gave him the utmost freedom, leaving him carefree without an imposed education or restrictions. At seven years old, his grandfather, whom he adored, died, and he went back to live with his parents.[4] He was profoundly affected by his grandfather's death, and again by the death of his childhood sweetheart and cousin Shashi from typhoid when he was 15, leading to an extraordinary preoccupation with death that lasted throughout much of his childhood and youth.[7]

In his school years, he was a rebellious, but gifted student, and a formidable debater.[8] As a youth, Osho became an atheist; he took an interest in hypnosis and was briefly associated with communism, socialism and two Indian independence movements: the Indian National Army and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.[8][4] He began speaking in public, initially at the annual Sarva Dharma Sammelan held at Jabalpur, organised by the Taranpanthi Jain community into which he was born (he participated there from 1951 to 1968).[9] He resisted his parents' pressure to get married.[10]

Osho later said he became spiritually enlightened on 21 March 1953, when he was 21 years old.[11] He said he dropped all effort and hope.[12] After what he describes as an intense seven-day process he says he went out at night to the Bhanvartal garden in Jabalpur, where he sat under a tree:[11]

The moment I entered the garden everything became luminous, it was all over the place – the benediction, the blessedness. I could see the trees for the first time – their green, their life, their very sap running. The whole garden was asleep, the trees were asleep. But I could see the whole garden alive, even the small grass leaves were so beautiful. I looked around. One tree was tremendously luminous – the maulshree tree. It attracted me, it pulled me towards itself. I had not chosen it, god himself has chosen it. I went to the tree, I sat under the tree. As I sat there things started settling. The whole universe became a benediction.[13]

He completed his studies at D. N. Jain College and the University of Sagar,[14] receiving a B.A. (1955) and an M.A. (1957, with distinction) in philosophy.[15] He then taught philosophy, first at Raipur Sanskrit College, and then, from 1958, as a lecturer at Jabalpur University.[15][16]

1960–1970

In 1960, Osho was promoted to professor at Jabalpur University.[16] In parallel to his university job, he travelled throughout India, giving lectures critical of socialism and Gandhi, under the name Acharya Rajneesh (Acharya means teacher or professor; Rajneesh was a nickname he had acquired in childhood).[16][8][17] Socialism and Gandhi, he said, both glorified poverty rather than rejecting it.[18] To escape its poverty and backwardness, India needed capitalism, science, modern technology and birth control.[8] He also criticised orthodox Hinduism, saying that Brahminic religion was sterile, and condemning all political and religious systems as hypocritical.[18] Such statements made him controversial, but also brought him a great deal of attention.[8]

Soon, he gained a loyal following that included a number of wealthy merchants and businessmen.[19] These sought individual consultations from him about their spiritual development and daily life, in return for donations – a commonplace arrangement in India, where people seek guidance from learned or holy individuals the way people elsewhere might consult a psychologist or counsellor.[19] The rapid growth of his practice, however, was somewhat out of the ordinary, suggesting that he had an uncommon talent as a spiritual therapist.[19] From 1962, he began to lead 3- to 10-day meditation camps, and the first meditation centres (Jivan Jagruti Kendras) started to emerge around his teaching, then known as the Life Awakening Movement (Jivan Jagruti Andolan).[20] After a speaking tour in 1966, he resigned from his teaching post.[16]

In a 1968 lecture series, later published under the title From Sex to Superconsciousness, he scandalised Hindu leaders by calling for freer acceptance of sex.[21] His advocacy of sexual freedom caused public disapproval in India, and he became known as the "sex guru" in the press.[22] When he was invited in 1969 – despite the misgivings of some Hindu leaders – to speak at the Second World Hindu Conference, he used the occasion to raise controversy again.[21] In his speech, he said that "any religion which considers life meaningless and full of misery, and teaches the hatred of life, is not a true religion. Religion is an art that shows how to enjoy life."[23] He characterised priests as being motivated by self-interest, incensing the shankaracharya of Puri, who tried in vain to have his lecture stopped.[23]

In 1969, a group of Osho's friends established a foundation to support his work. At the end of June 1970, he left Jabalpur and moved to Mumbai.[24] On September 26, 1970, he initiated his first disciple or sannyasin at an outdoor meditation camp, one of the large gatherings where he lectured and guided group meditations. His concept of neo-sannyas entailed wearing the traditional orange dress of ascetic Hindu holy men, including a mala (beaded necklace) carrying a locket with his picture.[25] However, his sannyasins were expected to follow a celebratory, rather than ascetic lifestyle, renouncing only that which prevented them from living totally in the present.[26]

In December 1970, Osho moved to Woodlands Apartments in Mumbai, where he gave lectures and received visitors, among them the first Western visitors.[24] He now travelled very rarely, and stopped speaking at open public meetings.[24]

1971–1980

In 1971, he adopted the title Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.[27] Shree means Sir or Mister; the Sanskrit title Bhagwan means "blessed one", indicating a human being in whom the divine is no longer hidden, but apparent.[28][29]

The hot, humid climate of Mumbai appeared to have proved detrimental to his health; he had developed diabetes, asthma and numerous allergies.[27] So, in 1974, on the 21st anniversary of his enlightenment,[30] he and his group moved from the Mumbai apartment to a property in Koregaon Park, Pune, which was purchased with the help of Catherine Venizelos (Ma Yoga Mukta), a Greek shipping heiress.[31] Osho taught at the Pune Ashram from 1974 to 1981.

The two adjoining houses and six acres of land became the nucleus of an Ashram, and those two buildings are still at the heart of the present-day Osho International Meditation Resort. This space allowed for the regular audio recording of his discourses and, later, video recording and printing for worldwide distribution, which enabled him to reach far larger audiences internationally. The number of Western visitors increased sharply, leading to constant expansion.[32] The Ashram soon featured an arts-and-crafts centre that turned out clothing, jewelry, ceramics and organic cosmetics and put on performances of theatre, music and mime.[33]

Following the arrival of several therapists from the Human Potential Movement[34] in the early seventies, the Ashram began to offer a growing number of therapy groups as well as meditations.[35] The therapy groups became a major source of income for the ashram.[35]

A typical day in the Ashram began at 6:00 a.m. with Dynamic Meditation.[35] At 8:00 a.m., Osho gave a 60 to 90-minute spontaneous lecture in the Ashram's "Buddha Hall" auditorium, either commenting on literature from a religious tradition, or answering questions sent in by visitors and disciples.[35] Until 1981, lecture series held in Hindi alternated with series held in English.[36] During the day, various meditations and therapies took place, whose intensity was ascribed to the spiritual energy of Osho's "buddhafield".[37] Evenings were for darshans, where Osho engaged in personal conversation with small numbers of individual disciples or visitors.[33] Sannyasins came for darshan when departing or returning to the Ashram, or if they had an issue that they wanted to discuss with Osho.[37]

To decide which therapies to participate in, visitors either consulted Osho or made selections according to their own preferences.[35] Some of the early therapy groups in the Ashram, such as the Encounter group, were experimental and very controversial, allowing a degree of physical violence as well as sexual encounters between participants.[35][38] Conflicting reports of injuries sustained in encounter group sessions began to appear in the press.[39][40][41] Violence in the therapy groups eventually ended in January 1979, when the Ashram issued a press release stating that violence "had fulfilled its function within the overall context of the Ashram as an evolving spiritual commune."[42]

Besides the controversy around the therapies, allegations of drug use amongst sannyasins began to mar the Ashram's image.[43] Some Western sannyasins were financing their extended stays in India through prostitution and drug running; some were caught and ended up in prison.[44][45] A few sannyasins later claimed that, while Osho was not directly involved, they discussed such plans and activities with him in darshan, and he gave his blessing.[46]

The Pune Ashram was, by all accounts, an exciting and intense place to be, with an emotionally charged, madhouse-carnival atmosphere.[33][37] Many observers noted that Osho's lecture style changed in the late seventies, becoming intellectually less focused and featuring an increasing number of jokes intended to shock or amuse his audience.[47]

By the latter half of the 1970s it had become clear that the property in Pune was too small to contain the rapid growth of the Ashram and Osho asked that somewhere larger be found.[47] Sannyasins from around India started looking for property that could be purchased and used for a larger Ashram and alternatives were found, including in the province of Kutch, Gujarat and in the Himalayas.[47][48] Nothing came of many of the ideas, although a castle at Saswad, in the hills above Pune, was purchased and work started on a community there.[48]

However, plans for a large utopian commune in India were never implemented, as mounting tensions between the Ashram and the conservative Hindu government led by Morarji Desai resulted in an impasse.[48] Land use approval was denied and, more importantly, the government stopped issuing visas to foreign visitors who indicated the Ashram as their main destination in India.[49]

In addition, Desai's government cancelled the tax-exempt status of the Ashram, resulting in a claim of current and back taxes estimated at $5 million.[50] Conflicts with various Indian religious leaders added to the situation – by 1980, the Ashram had become so controversial that Indira Gandhi, despite a previous association between Osho and the National Congress Party dating back to his early speeches made in the sixties, was unwilling to intercede for it after her return to power.[50] During one of Osho's discourses in May 1980, an attempt on his life was made by a young Hindu fundamentalist.[47][51]

1981–1985

By 1981, Osho's Ashram hosted 30,000 visitors per year.[52] On 10 April 1981, having discoursed daily for nearly 15 years, Osho entered a three-and-a-half-year period of self-imposed public silence,[48] and satsangs – silent sitting and music, with readings from spiritual works such as Khalil Gibran's The Prophet or the Isha Upanishad – took the place of his discourses.[53] On 1 June 1981, Osho travelled to the United States on a medical visa; he now also suffered from a persistent and very painful back problem.[54][55] The move seems to have been instigated by Osho's secretary, Ma Anand Sheela, who said she wished to ensure the availability of medical facilities in the event of any further deterioration in Osho's health and generally considered America a more suitable location for the new commune.[54][55][56] The various conflicts that had marred the period preceding his departure from Pune played a role as well.[55][57]

Osho spent several months in Montclair, New Jersey.[58] On 13 June 1981, Sheela's husband bought, for US$5.75 million, a 64,229-acre (260 km2) ranch located across two Oregon counties (Wasco and Jefferson), previously known as "The Big Muddy Ranch".[59] The following month, work began on setting up the so-called Rancho Rajneesh commune; Osho moved there in late August.[60]

Within a year of arriving, Osho's followers had become embroiled in a series of legal battles with their neighbours, the principal conflict relating to land use.[61] This conflict escalated to bitter hostility, and over the following years, the commune was subject to consistent and coordinated pressures from various coalitions of Oregon residents.[61][62] In May of 1982, the residents of Rancho Rajneesh (having grown larger in number than the local inhabitants) voted to incorporate the city of Rajneeshpuram.[61]

Osho resided at Rajneeshpuram, living in a purpose-built trailer complex with an indoor swimming pool and other amenities. He achieved notoriety for the large number of Rolls-Royce luxury cars[63] that his followers bought for his use, eventually numbering 93 vehicles.[64][65]

As part of his withdrawal from public life, Osho had given Ma Anand Sheela limited power of attorney in 1981, and removed the limits in 1982.[66] In 1983, Sheela announced that he would henceforth speak only with her.[67] He would later claim that she kept him in ignorance.[66] Many sannyasins expressed doubts about whether Sheela truly represented Osho.[68] An increasing number of dissidents left Rajneeshpuram, citing disagreements with Sheela's autocratic leadership style.[68]

The following years saw an increased emphasis on Osho's apocalyptic vision that the conventional world would destroy itself by nuclear war or other disasters sometime in the 1990s.[69] Osho had said as early as 1964 that "the third and last war is now on the way", and had commented in the intervening years on the need to create a "new humanity" to avoid global suicide.[70] By the early 1980s, this had become the basis for a new exclusivism, with a 1983 article in the Rajneesh Foundation Newsletter announcing that "Rajneeshism is creating a Noah's Ark of consciousness ... I say to you that except this there is no other way".[70] These warnings contributed to an increased sense of urgency in getting the Oregon commune established.[70]

In 1984, Sheela announced that Osho had predicted the death of two-thirds of humanity from AIDS.[70][71] As a precaution, sannyasins were required to wear rubber gloves and condoms while making love and to refrain from kissing.[72][73] This was widely seen as an extreme overreaction; AIDS was not considered a heterosexual disease at the time, and the use of condoms was not yet widely recommended for AIDS prevention.[74]

Osho ended his period of public silence in October 1984, announcing that it was time for him to "speak his own truths."[75] In July 1985, he resumed his daily public discourses in the commune's purpose-built, two-acre meditation hall. According to statements he made to the press, he did so against Sheela's wishes.[76]

On 16 September 1985, Sheela and her entire management team having suddenly left the commune for Europe a few days prior, Osho held a press conference in which he labelled Sheela and her associates a "gang of fascists."[77] He accused them of having committed a number of serious crimes, most of these dating back to 1984, and invited the authorities to investigate.[77] The alleged crimes, which he stated had been committed without his knowledge or consent, included the attempted murder of his personal physician, poisonings of public officials, wiretapping and bugging within the commune and within his own home, and a bioterror attack on the citizens of The Dalles, Oregon, using salmonella.[77] The subsequent investigation by the U.S. authorities confirmed these accusations and resulted in the conviction of Sheela and several of her lieutenants.[78] The salmonella attack has been described as the only confirmed instance of chemical or biological terrorism to have occurred in the United States.[79]

Osho claimed that because he was in silence and isolation, meeting only with Sheela, he was unaware of the crimes committed by the Rajneeshpuram leadership until Sheela and her "gang" left, and sannyasins came forward to inform him.[80] A number of commentators have stated that in their view Sheela was being used as a convenient scapegoat.[80][81][82] Others have pointed to the fact that although Sheela had bugged Osho's living quarters and made her tapes available to the U.S. authorities as part of her own plea bargain, no evidence has ever come to light that Osho had any part in her crimes.[83][84][85]

On 23 October 1985, a federal grand jury issued a thirty-five-count indictment charging Osho and several other disciples with conspiracy to evade immigration laws.[86] The indictment was returned in camera, but word was leaked to Osho's lawyer.[86] Negotiations to allow Osho to surrender to authorities in Portland if a warrant were issued failed.[86][87] Tension peaked amid rumours of a National Guard takeover, a planned violent arrest of Osho and fears of shooting.[88] On 28 October 1985, Osho, his personal physician and a small number of sannyasins accompanying them were arrested without a warrant aboard a rented Learjet at a North Carolina airstrip; the group were en route to Bermuda ($58,000 in cash and 35 watches and bracelets worth $1 million were also found on the aircraft).[89][90][88] Osho had by all accounts been neither informed of the impending arrest nor of the reasons for the journey.[87]

Osho's imprisonment and transfer across the country took the form of a public spectacle – he was displayed in chains, held first in North Carolina, then Oklahoma, and finally in Portland.[91] Officials took the full ten days legally available to them to transfer him from North Carolina to Portland for arraignment.[91] After initially pleading not guilty to all charges and being released on bail, Osho, on the advice of his lawyers, entered an "Alford plea" – through which a suspect does not admit guilt, but does concede there is enough evidence to convict him – to one count of making false statements to an immigration official, and one count of conspiracy to have followers stay in the country illegally by having them enter into sham marriages.[92] Under the deal his lawyers made with the United States Attorney's office, he was given a 10-year suspended sentence and placed on five years' probation; in addition, he agreed to pay $400,000 in fines and prosecution costs, to leave the United States and not to return for at least five years without the permission of the United States Attorney General.[78][90][93]

1986–1990

Osho then began a somewhat enforced world tour, speaking in Nepal, Crete and Uruguay, among others.[94][95] Being refused entry visas by twenty-one different countries, he returned to India in July 1986, and in January 1987, to his old Ashram in Pune, India.[96]

He resumed discoursing there, although with interruptions due to intermittent ill health.[97] Publishing efforts and therapy courses quickly resumed as well, though now in less controversial style, and the Ashram experienced a renewed period of expansion.[97] It now presented itself as a "Multiversity", a place where therapy was to function as a bridge to meditation.[97] Osho devised a number of new meditation techniques, among them the "Mystic Rose" method, and, after a gap of more than ten years, began to lead meditations personally again.[97]

Among his followers, the previous preference for communal living styles receded, most of them preferring to live ordinary and independent lives in society.[98] The former red or orange dress code for sannyasins, which had been optional for some time, was finally abandoned in 1987.[98]

In November 1987, Osho expressed his belief that his deteriorating health was the result of some form of poison administered to him by the U.S. authorities during the twelve days he was held without bail in various U.S. prisons.[99] His doctors hypothesised that he had been poisoned by radiation and thallium, and that he must have slept on his right side on a deliberately irradiated mattress, since his symptoms were concentrated on the right side of his body.[99] This allegation, as disseminated by Osho's one-time attorney, Philip J. Toelkes (Swami Prem Niren), was dismissed outright by U.S. attorney Charles H. Hunter, who stated: "It's a total and complete fiction and you have to consider the source ... the man has no credibility." Indeed, Toelkes conceded that there was no evidence to support the claim.[100] A less sinister explanation is that Osho, who had been a diabetic for many years, may have suffered from a series of systemic breakdowns in the final stages of his chronic disease, perhaps exacerbated by the stress he had experienced.[99]

From early 1988, his discourses focused exclusively on Zen.[97] In late December 1988, he said he no longer wished to be referred to as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, and in February 1989 took the name Osho.[97] His health continued to weaken, and he delivered his last public discourse in April 1989.[99] In the remaining months of that year, he only sat in silence with his followers.[99]

On January 19, 1990 Osho died, aged 58, with heart failure being the publicly reported cause. His ashes were placed in his newly built bedroom in one of the main buildings (LaoTsu House) at the Pune Ashram. The epitaph reads, "OSHO. Never Born, Never Died. Only Visited this Planet Earth between Dec 11 1931 – Jan 19 1990."

Legacy

While Osho's teachings met with strong rejection in his home country during his lifetime, there has been a sea change in Indian public opinion since Osho's death.[101] As early as 1991, an influential Indian newspaper counted Osho, among figures such as Gautama Buddha and Mahatma Gandhi, among the ten people who had most changed India's destiny; in Osho's case, by "liberating the minds of future generations from the shackles of religiosity and conformism".[102] Since then, his teachings have progressively become part of the cultural mainstream of India[101][103] and Nepal,[104][105] perhaps in part because of his status as a figure who had a large Western following.[2]

Osho is one of only two authors whose entire works have been placed in the Library of India's National Parliament in New Delhi (the other is Mahatma Gandhi).[101] Excerpts and quotes from his works appear regularly in the Times of India and many other Indian newspapers. Prominent admirers include the Indian Prime Minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh,[106] and the noted Indian novelist and journalist, Khushwant Singh.[106] The Osho disciple Vinod Khanna, who worked as Osho's gardener in Rajneeshpuram,[107] served as India's Minister of State for External Affairs from 2003 to 2004.[108]

Over 650 books[109] are credited to Osho, expressing his views on all facets of human existence.[62] Virtually all of them are renderings of his taped discourses.[62] His books are available in 55 different languages[110] and have entered best-seller lists in such varied countries as Italy and South Korea.[111][102]

After almost two decades of controversy and a decade of accommodation, Osho's movement has established itself in the international market of new religions.[19] His followers have redefined his contributions, reframing central elements of his teaching so as to make them appear less controversial to outsiders.[19] Societies in North America and Western Europe have met them half-way, becoming more accommodating to spiritual topics such as yoga and meditation.[19] His followers run stress management seminars for corporate clients such as IBM and BMW, making between $15 and $45 million annually in the U.S.[112][113]

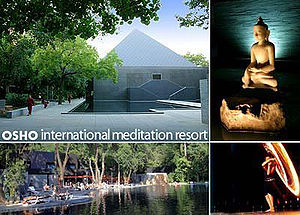

Osho's Ashram in Pune has become the Osho International Meditation Resort,[114] one of India's main tourist attractions.[115][116] According to press reports, it attracts some 200,000 people from all over the world each year;[106][117] prominent visitors have included politicians, media personalities and the Dalai Lama.[115] HIV/AIDS is still a concern for the Osho movement, and AIDS tests are mandatory for those wishing to enter the resort.[118]

Teachings

Osho's teachings were not static but changed in emphasis over time.[119] His lectures were not presented in a dry, academic setting, but interspersed with jokes, and delivered with an oratory that many found spellbinding.[120][121] He revelled in paradox and inconsistency, making it difficult to present more than a flavour of his work.[119]

Osho was very well read.[122] Conversant with all the Eastern religious traditions, he also drew on a great number of Western influences in his teaching.[123]

On the ego: man as a machine

Osho's view of man as a machine, condemned to the helpless acting out of unconscious, neurotic patterns, reflects the thought of Gurdjieff and Freud.[122][124] His vision of the "new man" who transcends the constraints of convention is reminiscent of Nietzsche's Beyond Good and Evil.[125] His views on sexual liberation bear comparison to the thought of D. H. Lawrence.[126] And while his contemporary Jiddu Krishnamurti does not seem to have been too fond of Osho, there are clear similarities between their respective teachings.[122]

Ultimately, Osho's message was a positive one.[127] He taught that we are all potential Buddhas, with the capacity for enlightenment.[127] According to him, every human being is capable of experiencing unconditional love and of responding rather than reacting to life.[127] He said: "You are truth. You are love. You are bliss. You are freedom."[128] He suggested that it is possible to experience innate divinity and to be conscious of "who we really are", even though our egos usually prevent us from enjoying this experience.[127] "When the ego is gone, the whole individuality arises in its crystal purity."[129] The problem, he said, is how to bypass the ego so that our innate being can flower; how to move from the periphery to the centre.[127]

Osho views the mind first and foremost as a mechanism for survival, replicating behavioural strategies that have proved successful in the past.[127] But by repeating the past, he says, we lose the ability to live authentically in the present.[127] We continually repress what we genuinely feel, closing ourselves off from experiencing the joy that arises naturally when we move into the present.[127][130] "The mind has no inherent capacity for joy. ... It only thinks about joy."[131] The result, he states, is that we unconsciously poison ourselves with various neuroses, jealousies, fears, etc., rather than living in joyous, authentic awareness.[130] By repressing sexual feelings, for example, we hope to pretend they do not exist.[130] But repression only leads to the re-emergence of these feelings in another guise to haunt our lives.[130] The result is a society that is obsessed with sex.[130] Instead of repressing, he argues, we should accept ourselves unconditionally.[130] "We have been repressing anger, greed, sex ... And that's why every human being is stinking. ... Let it become manure, ... and you will have great flowers blossoming in you."[132] This solution could not be intellectually understood, as the mind would only assimilate it as one more piece of baggage: instead, what was needed was meditation.[130]

On meditation

According to Osho, meditation is not just a practice, but a state of awareness that can be maintained in every moment.[130] He used Western psychotherapy as a means of preparing for meditation – a way to become aware of one's mental and emotional hang-ups – and also introduced his own, "Active Meditation" techniques, characterised by alternating stages of physical activity and silence.[133] In all, he suggested over a hundred meditation techniques.[133]

The most famous of these remains his first, known today as OSHO Dynamic Meditation.[133] This method has been described as a kind of microcosm of Osho's outlook.[134] It comprises five stages that are accompanied by music (except for stage 4).[133] In the first, the person engages in ten minutes of rapid breathing through the nose.[133] The second ten minutes are for catharsis: "[L]et whatever is happening happen. ... Laugh, shout, scream, jump, shake – whatever you feel to do, do it!"[133] For the next ten minutes, the person jumps up and down with their arms raised, shouting Hoo! each time they land on the flats of their feet.[135] In the fourth, silent stage, the person freezes, remaining completely motionless for fifteen minutes, and witnessing everything that is happening to them.[135] The last stage of the meditation consists of fifteen minutes of dancing and celebration.[135]

There are other active meditation techniques, like OSHO Kundalini Meditation and OSHO Nadabrahma Meditation, which are less animated, although they also include physical activity of one sort or another.[133] His final formal technique is called OSHO Mystic Rose, comprising three hours of laughing every day for the first week, three hours of weeping each day for the second, with the third week for silent meditation. The result of these processes is said to be the experience of "witnessing", enabling the "jump into awareness".[133]

Osho believed such cathartic methods were necessary, since it was very difficult for people of today to just sit and be in meditation. Once the methods had provided a glimpse of meditation, people would be able to use other methods without difficulty.[136]

On the function of the master

Another key ingredient of his teaching is his own presence as a master: "A Master shares his being with you, not his philosophy. ... He never does anything to the disciple."[137] He delighted in being paradoxical and engaging in behaviour that seemed entirely at odds with traditional images of enlightened individuals.[137] All such behaviour, however capricious and difficult to accept, was explained as "a technique for transformation" to push people "beyond the mind."[137] The initiation he offered his followers was another such device: "... if your being can communicate with me, it becomes a communion. ... It is the highest form of communication possible: a transmission without words. Our beings merge. This is possible only if you become a disciple."[137] Ultimately though, Osho even deconstructed his own authority.[138] He emphasised that anything and everything could become an opportunity for meditation.[137]

On renunciation

Osho saw his sannyas as a totally new form of spiritual discipline, or "a totally ancient one which had been completely forgotten".[139] He felt traditional sannyas had turned into a mere system of social renunciation and imitation.[139] His neo-sannyas emphasised complete inner freedom and responsibility of the individual to himself, demanding no superficial behavioral changes, but a deeper, inner transformation.[139] Desires were to be transcended, accepted and surpassed rather than denied.[139] Once this inner flowering had taken place, even sex would be left behind.[139]

Osho said that he was "the rich man's guru" and taught that material poverty was not a genuine spiritual value.[140] He had himself photographed wearing sumptuous clothing and hand-made watches,[141] and while in Oregon drove a different Rolls-Royce each day – his followers reportedly wanted to buy him 365 of them, one for each day of the year.[64] Publicity shots of the Rolls-Royces (93 in the end) were sent to the press.[142][140] As a conscious display of wealth, they reflected both Osho's embrace of the material world and his desire to provoke American sensibilities, much as he had enjoyed offending Indian sensibilities earlier.[143][140]

On the "New Man"

By the aforementioned means, Osho hoped to create "a new man" combining the spirituality of Gautama Buddha with the zest for life embodied by Zorba the Greek in the novel by Nikos Kazantzakis:[137] "He should be as accurate and objective as a scientist ... as sensitive, as full of heart, as a poet ... [and as] rooted deep down in his being as the mystic."[144] This new man, "Zorba the Buddha", should reject neither science nor spirituality, but embrace them both.[137] He should be "all for matter, and all for spirit."[143] Osho believed humanity to be threatened with extinction due to over-population, impending nuclear holocaust, and diseases such as AIDS, and thought that many of society's ills could be remedied by scientific means.[137]

The new man would no longer be trapped in institutions such as family, marriage, political ideologies, or religions.[145] In this respect, Osho has much in common with other counter-culture gurus, and perhaps even certain postmodern and deconstructional thinkers.[146] His term the "new man" applied to men and women equally, whose roles he saw as complementary; indeed, most of his movement's leadership positions were held by women.[145]

Summary

In the course of his life, Osho spoke on all the major spiritual traditions, including Tantra, Taoism, Christianity, Buddhism, Yoga, the teachings of a variety of mystics, and on sacred scriptures such as the Upanishads and the Guru Granth Sahib.[145] But the topic that predominated, and on which he came to focus exclusively towards the end of his life, was Zen.[145]

If Osho's teachings seemed mad, playful or simply absurd, this was no doubt intentional: as an explicitly "self-deconstructing" or "self-parodying" guru, his teaching as a whole was said to be nothing more than a "game" or a joke.[146] His early lectures were famous for their humour and their refusal to take anything seriously.[146] His message of sexual, emotional, spiritual, and institutional liberation, as well as his contrariness, ensured that his life was surrounded by conjecture, rumour, and controversy.[145]

Reception

Osho was notorious all his life, becoming known as the "sex guru" in India, and as the "Rolls-Royce guru" in the United States.[148] He is generally considered one of the most controversial spiritual leaders to have emerged from India in the twentieth century.[149] Surrounded by scandals and accusations, he continued to attract crowds and retained a large number of disciples to the end of his life and beyond.[2][149]

Osho attacked traditional concepts of nationalism, expressed undisguised contempt for politicians and poked fun at leading figures of various religions.[150] Religious leaders in turn found his arrogance unbearable.[151] His ideas on sex, marriage, family and relationships contradicted traditional views of these matters and aroused a great deal of anger and opposition around the world.[58][152] According to the Indian sociologist Uday Mehta, his appeal to his Western disciples was based on his social experiments, which established a philosophical connection between the Eastern guru tradition and the Western growth movement.[149]

Appraisal as a thinker and speaker

There are widely diverging views on Osho's qualities as a thinker and speaker.

Khushwant Singh, eminent author, historian and former editor of the Times of India, has described him as "the most original thinker that India has produced: the most erudite, the most clearheaded and the most innovative",[153] writing that "Osho is really a free-thinking agnostic. He [...] can explain the most abstract conception in simple language illustrated with witty anecdotes. He mocks gods, prophets, scriptures and religious practices and gives a totally new dimension to religion."[154] Osho's commentary on the Sikh scripture known as Japuji was hailed as the best available by Giani Zail Singh, the former President of India.[101]

The German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk has called Osho a "Wittgenstein of religions", "one of the greatest figures of the 20th century"; in his view Osho had performed "a radical deconstruction of the word games played by the world's religions."[155] The American poet and Rumi translator Coleman Barks likened reading Osho's discourses to the "taste of fresh springwater."[156] The American author Tom Robbins wrote, "I am not, nor have I ever been, a disciple ... [of Osho], but I’ve read enough of his brilliant books to be convinced that he was the greatest spiritual teacher of the 20th century – and I’ve read enough vicious propaganda and slanted reports to suspect that he was one of the most maligned figures in history."[153]

Others, expressing themselves in a context that was almost completely hostile, cynical or sarcastic about Osho's movement, found themselves unimpressed by his oratory.[157] The author and broadcaster Clive James, for example, scornfully referred to him as "Bagwash", a title which he found it "impossible not to call him if you have ever sat in a laundrette and watched your underwear revolve soggily for hours while exuding grey suds. The Bagwash talks the way that looks."[158] Responding to an enthusiastic review of Osho's talks by Bernard Levin in The Times, Dominik Wujastyk, also writing in The Times, similarly expressed his opinion that "the talk was of an extremely low standard, often factually wrong, and wearyingly repetitive."[158][159]

The religious scholar Hugh B. Urban, Assistant Professor of Religion and Comparative Studies at Ohio State University, found Osho's teachings "neither original nor particularly profound", but "consisting in large part of material borrowed from Eastern and Western philosophies."[146] What he found most original about Osho was his keen commercial instinct or "marketing strategy", by which he adapted these teachings to meet the changing desires of his audience,[146] a theme also picked up on by Gita Mehta in her book Karma Cola: Marketing the Mystic East.[160] Bob Mullan, a sociologist from the University of East Anglia, summed up Osho's vast body of writings as a kind of "postmodern pastiche". Although he considered his range and imagination second to none, and acknowledged that many of his statements were quite insightful and moving, even profound at times, what remained was a "potpourri of essentially counter-culturalist and post-counter-culturalist ideas, namely: strive for 'love' and freedom, live for the moment, self is important – 'you are okay', there is mystery in life, the fun ethic, the individual is responsible for his own destiny, drop ego (including fear and guilt), and so on."[161]

Charisma

Most people who saw Osho in person, whether detractors, admirers, sannyasins or disaffected followers, appear to agree that he was possessed of extraordinary charisma.[162] Many sannyasins and ex-followers have stated that hearing Osho speak, they "fell in love with him."[162][163] Sally Belfrage, who penned a rather disparaging account of life in Osho's Ashram in India, nevertheless confessed on viewing him in person that "he was AB-SO-LUTE-LY RI-VET-ING."[162] Frances FitzGerald, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who wrote a study of Rajneeshpuram for The New Yorker magazine, stated, "He was – in a way that could not be appreciated on videotape – a brilliant lecturer ... what I had not gathered from reading the lecturers was his talent as a comedian. The jokes sounded better than they read, but far better were the comic riffs he would go off into once or twice in a lecture – little experiments in language and the play of associations. Also, Rajneesh was a world-class hypnotist. One of his lectures ended with a description of a dewdrop sliding off a lotus leaf and being carried down a stream to the ocean. It put virtually everyone in his audience into an alpha-wave state at ten in the morning."[164] Hugh Milne, an ex-follower, writes of his first meeting with Osho, "Whatever this marvellous being is doing, it is far more than the words that are passing between us. There is no invasion of privacy, no alarm, but it is as if his soul is slowly slipping inside mine, and in a split second transferring vital information.[165]

Narcissism

A number of commentators have suggested that Osho, like other charismatic leaders, had a narcissistic personality.[166][167][168] In his paper The Narcissistic Guru: A Profile of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, Ronald O. Clarke, Emeritus Professor of Religious Studies at Oregon State University, argued that Osho exhibited a grandiose sense of self-importance and uniqueness; a preoccupation with fantasies of unlimited success; a need for constant attention and admiration; a set of characteristic responses to threats to self-esteem; disturbances in interpersonal relationships; a preoccupation with grooming combined with frequent resorting to prevarication or outright lying; and a lack of empathy.[168] Drawing on Osho's reminiscences of his childhood in his book Glimpses of a Golden Childhood, he suggests that Osho suffered from a fundamental lack of parental discipline, due to his growing up in the care of overindulgent grandparents.[168] Osho's self-avowed Buddha status, he concludes, was part of a delusional system associated with his narcissistic personality disorder; a condition of ego-inflation rather than egolessness.[168]

Alleged drug abuse

In Rajneeshpuram, Osho dictated three books while undergoing dental treatment under the influence of nitrous oxide (laughing gas): Glimpses of a Golden Childhood, Notes of a Madman, and Books I Have Loved.[169] Subsequently, there were allegations that Osho had been addicted to nitrous oxide gas.[170][171] In addition, Sheela claimed in a 1985 interview on the American CBS television show 60 Minutes that Osho took sixty milligrams of Valium every day.[171][172] When questioned by journalists about the allegations of daily Valium and nitrous oxide use, Osho categorically denied both, describing the allegations as "absolute lies".[173]

Planned biographical film

Guru of Sex has been a planned live action English language film about Osho, also known as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, written by Farrukh Dhondy.[174][175]

Development

Sir Ben Kingsley has been cast in the role of Osho.[176][177] The film is being written by MediaOne Ventures Ltd., which is a division of Chandigarh, India-based Compact Disc India Limited (CDI).[175] The film has a projected budget of USD$16 million, and will be shot in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, because the locations resemble the current Osho centre in Pune.[178][179][175] CDI has also signed a $20.15 million deal with the Los Angeles based company Motion Pixel Corporation to co-produce an animated soccer film called Goaaal!.[174][180] Voice actors signed on to Goaaal! include Ben Kingsley, Catherine Zeta Jones, Michael Douglas and Christina Aguilera.[180] Though the deals for both Goaaal! and Guru of Sex were signed by CDI, production will be handled by MediaOne Ventures.[174] The combined sales revenue of both films is projected at over $200 million.[174]

Response from Osho centres

Both the Osho Commune International in Pune and the Osho World Foundation in Delhi have not had favorable responses to news of the film.[178] Swami Chaitanya Keerti, editor of Osho World Magazine, stated "With such a title, it’s no mystery what kind of film it’s going to be," and said that the Osho centres will not cooperate with the film's production.[178] "We haven’t been contacted for any information, photographs or research for this film," said Ma Sadhana, a member of the Pune commune.[178] CDI chairman Suresh Kumar said that he contacted both of the Osho centres, but they refused to provide any help.[178] "We have called him a ‘guru of sex’ and obviously this is not how they would want him portrayed," said Kumar.[178]

Contents

The film is inspired by the life of Osho, and "will have a controversial theme of depicting the ‘not so sacred’ acts inside a holy cult."[181] The production company is taking steps to avoid legal controversies, and will refer to the main character as "Rajneesh" instead of "Osho", because Rajneesh is a more common name.[178] The film will chronicle Rajneesh's beginnings in Jabalpur and will follow his journey from India to the United States.[178] A disclaimer at the beginning of the film will state that "any resemblance to person, dead or alive, is incidental."[178] According to Suresh Kumar, "The climax makes the startling revelation that the guru of sex in fact never enjoyed sex."[178]

References

- Aveling, Harry (1994), The Laughing Swamis, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1118-6

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Aveling, Harry (ed.) (1999), Osho Rajneesh and His Disciples: Some Western Perceptions, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1599-8

{{citation}}:|first=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help). (Includes studies by Susan J. Palmer, Lewis F. Carter, Roy Wallis, Carl Latkin, Ronald O. Clarke and others previously published in various academic journals.)

- Bhawuk, Dharm P. S. (2003), "Culture's influence on creativity: the case of Indian spirituality", International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27 (1): Pages 1–22

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Carter, Lewis F. (1987), "The "New Renunciates" of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh: Observations and Identification of Problems of Interpreting New Religious Movements", Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 26 (2): Pages 148–172

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help), reprinted in Aveling 1999, pp. 175–218.

- Carrette, Jeremy; King, Richard (2004), Selling Spirituality: The Silent Takeover of Religion, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-41530-209-9.

- Carter, Lewis F. (1990), Charisma and Control in Rajneeshpuram: A Community without Shared Values, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-38554-7

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Carus, W. Seth (2002), Bioterrorism and Biocrimes (PDF), The Minerva Group, Inc., ISBN 1-41010-023-5

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Clarke, Ronald O. (1988), "The Narcissistic Guru: A Profile of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh", Free Inquiry (Spring 1988): Pages 33–35, 38–45

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help), reprinted in Aveling 1999, pp. 55–89.

- FitzGerald, Frances (22 Sept. 1986), "Rajneeshpuram", The New Yorker

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link).

- FitzGerald, Frances (29 Sept. 1986), "Rajneeshpuram", The New Yorker

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link).

- Fox, Judith M. (2002), Osho Rajneesh – Studies in Contemporary Religion Series, No. 4, Salt Lake City: Signature Books, ISBN 1-56085-156-2

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Goldman, Marion S. (1991), "Reviewed Work(s): Charisma and Control in Rajneeshpuram: The Role of Shared Values in the Creation of a Community by Lewis F. Carter", Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30 (4): pp. 557–558

{{citation}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Gordon, James S. (1987), The Golden Guru, Lexington, MA: The Stephen Greene Press, ISBN 0-8289-0630-0

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Heelas, Paul (1996), The New Age Movement: Religion, Culture and Society in the Age of Postmodernity, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-19332-4

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Huth, Fritz-Reinhold (1993), Das Selbstverständnis des Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh in seinen Reden über Jesus, Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Peter Lang GmbH (Studia Irenica, vol. 36), ISBN 3-631-45987-4

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Template:De icon.

- Joshi, Vasant (1982), The Awakened One, San Francisco, CA: Harper and Row, ISBN 0-06-064205-X

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Latkin, Carl A. (1992), "Seeing Red: A Social-Psychological Analysis", Sociological Analysis, 53 (3): Pages 257–271

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help), reprinted in Aveling 1999, pp. 337–361.

- Lewis, James R.; Petersen, Jesper Aagaard (eds.) (2005), Controversial New Religions, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 019515682X

{{citation}}:|first2=has generic name (help).

- Maslin, Janet (1981-11-13), "Ashram (1981) Life at an Ashram, Search for Inner Peace (movie review)", New York Times

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link).

- Mehta, Gita (1994), Karma Cola: Marketing the Mystic East, New York: Vintage, ISBN 0679754334

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Mehta, Uday (1993), Modern Godmen in India: A Sociological Appraisal, Bombay: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 81-7154-708-7

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Milne, Hugh (1986), Bhagwan: The God That Failed, London: Caliban Books, ISBN 0-85066-006-9

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help). (By Osho's one-time bodyguard.)

- Mullan, Bob (1983), Life as Laughter: Following Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, London, Boston, Melbourne and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul Books Ltd, ISBN 0-7102-0043-9

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Osho (2000), Autobiography of a Spiritually Incorrect Mystic, New York, NY: St. Martin's Griffin, ISBN 0-312-25457-1

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Osho (1985), Glimpses of a Golden Childhood, Rajneeshpuram: Rajneesh Foundation International, ISBN 0-88050-715-2

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Rebel Publishing House edition (1998) ISBN 81-7261-072-6.

- Palmer, Susan J. (1988), "Charisma and Abdication: A Study of the Leadership of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh", Sociological Analysis, 49 (2): Pages 119–135

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help), reprinted in Aveling 1999, pp. 363–394.

- Palmer, Susan J.; Sharma, Arvind (eds.) (1993), The Rajneesh Papers: Studies in a New Religious Movement, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1080-5

{{citation}}:|first2=has generic name (help).

- Prasad, Ram Chandra (1978), Rajneesh: The Mystic of Feeling, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 0896840239

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Sam (1997), Life of Osho (PDF), London: Sannyas

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Shunyo, Ma Prem (1993), My Diamond Days with Osho: The New Diamond Sutra, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1111-9

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Sloterdijk, Peter (1996), Selbstversuch: Ein Gespräch mit Carlos Oliveira, München, Wien: Carl Hanser Verlag, ISBN 3-446-18769-3

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Template:De icon.

- Storr, Anthony (1996), Feet of Clay – A Study of Gurus, London: Harper Collins, ISBN 000-255563-8

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Süss, Joachim (1996), Bhagwans Erbe, Munich: Claudius Verlag, ISBN 3-532-64010-4

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Template:De icon.

- Urban, Hugh B. (1996), "Zorba The Buddha: Capitalism, Charisma and the Cult of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh", Religion, 26 (2): Pages 161–182

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Urban, Hugh B. (2003), Tantra: Sex, Secrecy, Politics, and Power in the Study of Religion, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-23656-4

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Wallis, Roy (1986), "Religion as Fun? The Rajneesh Movement", Sociological Theory, Religion and Collective Action, Queen's University, Belfast: Pages 191–224

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help), reprinted in Aveling 1999, pp. 129–161.

Citations

- ^ Heelas 1996, pp. 22, 40, 68, 72, 77, 95–96

- ^ a b c Urban 2003, p. 242

- ^ Joshi 1982, p. 14

- ^ a b c Fox 2002, p. 9

- ^ Mullan 1983, p. 11

- ^ Osho 1985, p. passim

- ^ Joshi 1982, pp. 22–25, 31, 45–48

- ^ a b c d e FitzGerald 1986a, p. 77

- ^ Smarika, Sarva Dharma Sammelan, 1974, Taran Taran Samaj, Jabalpur

- ^ Interview with Howard Sattler, 6PR Radio, Australia, video available here

- ^ a b Mullan 1983, p. 12

- ^ "My Awakening". Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ Osho: The Discipline of Transcendence, Vol. 2, Chapter 11

- ^ "University of Sagar website". Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ a b Gordon 1987, p. 25

- ^ a b c d Carter 1990, p. 44

- ^ Gordon 1987, pp. 26–27

- ^ a b Fox 2002, p. 10

- ^ a b c d e f Lewis & Petersen 2005, p. 122 Cite error: The named reference "Lewis122" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Osho 2000, p. 224

- ^ a b Carter 1990, p. 45

- ^ Joshi 1982, pp. 1–4

- ^ a b Joshi 1982, p. 88

- ^ a b c Joshi 1982, pp. 94–103

- ^ Fox 2002, p. 12

- ^ Fox 2002, p. 11

- ^ a b FitzGerald 1986a, p. 78

- ^ Süss 1996, pp. 29–30

- ^ Macdonell Practical Sanskrit Dictionary (see entry for bhagavat, which includes bhagavan as the vocative case of bhagavat)

- ^ FitzGerald 1986a, p. 87

- ^ Carter 1990, pp. 48–54

- ^ Fox 2002, p. 15

- ^ a b c FitzGerald 1986a, p. 80

- ^ Fox 2002, p. 16

- ^ a b c d e f Fox 2002, p. 17

- ^ Mehta 1993, p. 93

- ^ a b c Fox 2002, p. 18

- ^ Maslin 1981

- ^ Karlen, N., Abramson, P.: Bhagwan's realm, in: Newsweek, December 3 1984

- ^ Prasad 1978

- ^ Mehta 1994, pp. 36–38

- ^ Gordon 1987, p. 84

- ^ Mitra, S., Draper, R., and Chengappa, R.: Rajneesh: Paradise lost, in: India Today, December 15 1985

- ^ Fox 2002, p. 20

- ^ Sam 1997, pp. 57–58, 80–83, 112–114

- ^ Fox 2002, p. 47

- ^ a b c d FitzGerald 1986a, p. 85

- ^ a b c d Fox 2002, p. 21

- ^ Goldman 1991

- ^ a b Carter 1990, pp. 63–64

- ^ Times of India article dated 18 Nov. 2002

- ^ Mitra, S., Draper, R., and Chengappa, R.: Rajneesh: Paradise lost, in: India Today, December 15 1985

- ^ Joshi 1982, p. 159

- ^ a b Fox 2002, p. 22

- ^ a b c Gordon 1987, pp. 93–94

- ^ Palmer 1988, p. 127, reprinted in Aveling 1999, p. 377

- ^ Guru in Cowboy Country, in: Asia Week, July 29 1983, pp. 26–36

- ^ a b New York Times article dated 16 Sep. 1981

- ^ Carter 1990, p. 133

- ^ Carter 1990, pp. 136–138

- ^ a b c Latkin 1992, reprinted in Aveling 1999, pp. 339–341

- ^ a b c Carter 1987, reprinted in Aveling 1999, pp. 182, 189

- ^ Wakin D. J., Rajneesh-Rolls Royce, Associated Press Writer, APpa 07/26 1407

- ^ a b The Hindu article dated 16 May 2004

- ^ Palmer 1988, p. 128, reprinted in Aveling 1999, p. 380

- ^ a b Palmer 1988, p. 127, reprinted in Aveling 1999, p. 378

- ^ FitzGerald 1986a, p. 94

- ^ a b FitzGerald 1986a, p. 93

- ^ Wallis 1986, reprinted in Aveling 1999, p. 156

- ^ a b c d Wallis 1986, reprinted in Aveling 1999, p. 157

- ^ Fox 2002, p. 26

- ^ Palmer 1988, p. 129, reprinted in Aveling 1999, p. 382

- ^ Rajneesh Times, 16, 1st October, 1984:6

- ^ Palmer & Sharma 1993, pp. 155–158

- ^ Fox 2002, p. 27

- ^ Osho: The Last Testament, Vol. 2, Chapter 29 (transcript of interview with Stern magazine and ZDF TV, Germany)

- ^ a b c FitzGerald 1986b, p. 108

- ^ a b Carter 1990, pp. 233–238

- ^ Carus 2002, p. 50

- ^ a b Mehta 1993, p. 118

- ^ Aveling 1994, p. 205

- ^ FitzGerald 1986b, p. 109

- ^ Aveling 1999, p. 17

- ^ Fox 2002, p. 50

- ^ Gordon 1987, p. 210

- ^ a b c FitzGerald 1986b, p. 110

- ^ a b Carter 1990, p. 232

- ^ a b Palmer & Sharma 1993, p. 52

- ^ Carter 1990, pp. 232, 233, 238

- ^ a b FitzGerald 1986b, p. 111

- ^ a b Carter 1990, pp. 234–235

- ^ Gordon 1987, pp. 199–201

- ^ Latkin 1992, reprinted in Aveling 1999, p. 342

- ^ Carter 1990, p. 241

- ^ Shunyo 1993, pp. 121, 131, 151

- ^ Fox 2002, p. 29

- ^ a b c d e f Fox 2002, p. 34

- ^ a b Fox 2002, pp. 32–33

- ^ a b c d e Fox 2002, pp. 35–36

- ^ Akre B. S.: Rajneesh Conspiracy, Associated Press Writer, Portland (APwa 12/15 1455)

- ^ a b c d Bombay High Court tax judgment, sections 12–14

- ^ a b Fox 2002, p. 42

- ^ APS Malhotra: In memoriam, The Hindu, 23 Sep. 2006

- ^ News Post India article dated 19 January 2008

- ^ Former prime minister of Nepal, Krishna Prasad Bhattarai, on a visit to the Kathmandu Osho commune

- ^ a b c San Francisco Chronicle article dated 29 Aug. 2004

- ^ The Tribune article dated 25 July 2002 (8th from the top)

- ^ Parliamentary Biography

- ^ Süss 1996, p. 45

- ^ Tehelka article dated 30 June 2007

- ^ PublishingTrends.com

- ^ Carrette & King 2004, p. 154

- ^ Heelas 1996, p. 63

- ^ Page on virtualpune.com

- ^ a b Fox 2002, p. 41

- ^ Indian Embassy website, section "A modern Ashram"

- ^ Willamette Week Online, Portland, Orgeon, article dated 2 Feb. 2000

- ^ Osho Meditation Resort Website FAQ

- ^ a b Fox 2002, p. 1

- ^ Fox 2002, pp. 1–2

- ^ Mullan 1983, p. 1

- ^ a b c Fox 2002, p. 1

- ^ Mullan 1983, p. 33

- ^ Prasad 1978, pp. 14–17

- ^ Carter 1987, reprinted in Aveling 1999, p. 209

- ^ Carter 1990, p. 50

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fox 2002, p. 3

- ^ Osho: The Goose Is Out, p. 286, quoted in Fox 2002, p. 3

- ^ Osho: The Goose Is Out, p. 142, quoted in Fox 2002, p. 3

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fox 2002, p. 4

- ^ Osho: The Goose Is Out, p. 13, quoted in Fox 2002, p. 4

- ^ Osho: Be Silent and Know, p. 36, quoted in Fox 2002, p. 4

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fox 2002, p. 5

- ^ Urban 1996, p. 172

- ^ a b c Osho: Meditation: The First and Last Freedom, p. 35

- ^ Interview with Riza Magazine, Italy, video available here

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fox 2002, p. 6

- ^ Urban 1996, p. 170

- ^ a b c d e Aveling 1994, p. 86

- ^ a b c Gordon 1987, p. 114

- ^ Times of India article dated 3 Jan. 2004

- ^ FitzGerald 1986a, p. 47

- ^ a b Lewis & Petersen 2005, p. 129

- ^ Osho: Philosophia Perennis, p. 10, quoted in Fox 2002, p. 6

- ^ a b c d e Fox 2002, p. 7

- ^ a b c d e Urban 1996, p. 169

- ^ Osho: Come Follow To You, Vol. 2, Chapter 4

- ^ Gordon 1987, p. 114

- ^ a b c Mehta 1993, p. 133

- ^ Joshi 1982, p. 1

- ^ Mehta 1993, p. 83

- ^ Joshi 1982, p. 2

- ^ a b Bhawuk 2003, p. 14

- ^ Khushwant Singh, writing in the Indian Express, December 25, 1988, quoted e.g. here

- ^ Sloterdijk 1996, p. 105

- ^ Introduction to Osho's book Just like that

- ^ Mullan 1983, p. 2

- ^ a b Mullan 1983, pp. 8–9

- ^ Obituary of Bernard Levin in The Daily Telegraph dated 10 August 2004

- ^ Mehta 1994

- ^ Mullan 1983, p. 48

- ^ a b c Palmer 1988, p. 122, reprinted in Aveling 1999, p. 368

- ^ Mullan 1983, p. 67

- ^ FitzGerald 1986b, p. 106

- ^ Milne 1986, p. 48

- ^ Storr 1996, p. 50

- ^ Huth 1993, pp. 204–226

- ^ a b c d Clarke 1988, reprinted in Aveling 1999, pp. 55–89

- ^ Shunyo 1993, p. 74

- ^ Fox 2002, p. 48

- ^ a b Storr 1996, p. 59

- ^ Charlotte Observer article dated 4 November 1985

- ^ Osho: The Last Testament, Vol. 4, Chapter 19 (transcript of an interview with German magazine, Der Spiegel)

- ^ a b c d Staff (June 18, 2007). "Indian animation takes giant leap forward: With the industry expected to grow at 30% per annum, companies like CDI are going full throttle through overseas listing and projections of making four international films a year". livemint.com (Partner: The Wall Street Journal). Hindustan Times Media Limited. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Vashisht, Dinker (August 5, 2007). "Gandhi will return as Rajneesh, via Chandigarh: Chandigarh firm ropes in Ben Kingsley for its film, Guru of Sex". The Sunday Express. Indian Express Newspapers (Mumbai) Ltd. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Bhushan, Nyay (June 19, 2007). "Indian film firms go Alternative: Bollywood producer latest to raise cash via AIM IPO". Hollywood Reporter. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Staff (June 16, 2007). "New Compact Disc Arm to List on London SE". Business Line. Kasturi & Sons Ltd.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mehta, Sunanda (August 11, 2007). "Osho centres disown Guru of Sex movie: Preacher will be called Rajneesh to avoid legal wrangles, climax more controversial, says film company". PUNE Newsline. Indian Express Newspapers (Mumbai) Ltd. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Staff (June 13, 2007). "Compact Disc to float subsidiary in UK". The Economic Times. Times Internet Limited. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Khanna, Ruchika M. (May 22, 2007). "Chandigarh firm to co-produce soccer flick". Tribune News Service. The Tribune Trust, Chandigarh, India. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Staff (June 14, 2007). "CDI's MediaOne Venture to float on AIM, UK". Moneycontrol India. e-Eighteen.com Ltd. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Further reading

- Appleton, Sue (1987), Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh: The Most Dangerous Man Since Jesus Christ, Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, ISBN 3-89338-001-9

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Belfrage, Sally (1981), Flowers of Emptiness: Reflections on an Ashram, New York, NY: Doubleday, ISBN 0-385-27162-X

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Bharti, Ma Satya (1981), Death Comes Dancing: Celebrating Life With Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, London, Boston, MA and Henley: Routledge, ISBN 0-7100-0705-1

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Bharti Franklin, Satya (1992), The Promise of Paradise: A Woman's Intimate Story of the Perils of Life With Rajneesh, Barrytown, NY: Station Hill Press, ISBN 0-88268-136-2

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- FitzGerald, Frances (1987), Cities on a Hill: A Journey Through Contemporary American Cultures, New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-55209-0

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help). (Includes a 135-page section on Rajneeshpuram previously published in two parts in The New Yorker magazine, Sept. 22 and Sept. 29 1986 editions.)

- Forman, Juliet (2002), Bhagwan: One Man Against the Whole Ugly Past of Humanity, Cologne: Rebel Publishing House, ISBN 3-893-38103-1

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Guest, Tim (2005), My Life in Orange: Growing up with the Guru, London: Granta Books, ISBN 1-862-07720-7

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Gunther, Bernard (Swami Deva Amit Prem) (1979), Dying for Enlightenment: Living with Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, New York, NY: Harper & Row, ISBN 0-06-063527-4

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Hamilton, Rosemary (1998), Hellbent for Enlightenment: Unmasking Sex, Power, and Death With a Notorious Master, Ashland, OR: White Cloud Press, ISBN 1-883991-15-3

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).

- Latkin, Carl A., "Feelings after the fall: former Rajneeshpuram Commune members' perceptions of and affiliation with the Rajneeshee movement", Sociology of Religion, 55 (1): Pages 65-74, retrieved 2008-05-04

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help).

- McCormack, Win (1985), Oregon Magazine: The Rajneesh Files 1981-86, Portland, OR: New Oregon Publishers, Inc.

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) ASIN B000DZUH6E.

- Meredith, George (1988), Bhagwan: The Most Godless Yet the Most Godly Man, Poona: Rebel Publishing House

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) ASIN B0000D65TA. (By Osho's personal physician.)

- Quick, Donna (1995), A Place Called Antelope: The Rajneesh Story, Ryderwood, WA: August Press, ISBN 0-9643118-0-1

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help).