Óscar Romero

The Most Reverend Blessed Óscar Romero y Galdámez | |

|---|---|

| Bishop and martyr | |

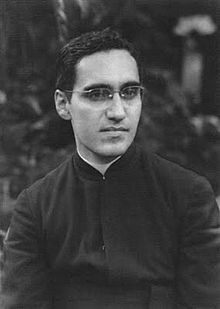

| File:Monseñor Romero 1979.jpg Romero c. 1979. | |

| Church | Roman Catholic Church |

| Archdiocese | San Salvador |

| See | San Salvador |

| Appointed | 3 February 1977 |

| Installed | 23 February 1977 |

| Term ended | 24 March 1980 |

| Predecessor | Luis Chávez |

| Successor | Arturo Rivera |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 4 April 1942 |

| Consecration | 21 June 1970 by Girolamo Prigione |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Óscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez 15 August 1917 Ciudad Barrios, San Miguel Department, El Salvador |

| Died | 24 March 1980 (aged 62) San Salvador, El Salvador |

| Buried | Metropolitan Cathedral of the Holy Savior, San Salvador, El Salvador |

| Nationality | Salvadoran |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Parents | Santos Romero & Guadalupe de Jesús Galdámez |

| Motto | Sentire cum Ecclesia (Feel with the Church) |

| Signature | |

| Coat of arms |  |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 24 March |

| Venerated in |

|

| Title as Saint | Bishop and martyr |

| Beatified | 23 May 2015 San Salvador, El Salvador by Cardinal Angelo Amato, S.D.B., representing Pope Francis |

| Attributes | Archbishop's attire |

| Patronage |

|

Óscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez (15 August 1917 – 24 March 1980) was a prelate of the Catholic Church in El Salvador, who served as the fourth Archbishop of San Salvador. He spoke out against poverty, social injustice, assassinations, and torture. In 1980, Romero was assassinated while offering Mass in the chapel of the Hospital of Divine Providence.

Pope Francis stated during Romero's beatification that "His ministry was distinguished by a particular attention to the most poor and marginalized."[3] Hailed as a hero by supporters of liberation theology inspired by his work, Romero, according to his biographer, "was not interested in liberation theology" but faithfully adhered to Catholic teachings on liberation and a preferential option for the poor,[4] desiring a social revolution based on interior reform. His spiritual life drew much early on from the spirituality of Opus Dei. While seen as a social conservative at his appointment as Archbishop in 1977, he was deeply affected by the murder of Rutilio Grande a few weeks after his own appointment and became more of a social activist from that time forward.

In 2010, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 24 March as the "International Day for the Right to the Truth Concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims" in recognition of the role of Archbishop Romero in defence of human rights. Romero actively denounced violations of the human rights of the most vulnerable people and defended the principles of protecting lives, promoting human dignity and opposition to all forms of violence.

In 1997, Pope John Paul II bestowed upon Romero the title of Servant of God, and a cause for beatification and canonization was opened for him. The cause stalled, but was reopened by Pope Benedict XVI in 2012. He was declared a martyr by Pope Francis on 3 February 2015, paving the way for his beatification which took place on 23 May 2015.

Latin American church groups often proclaim Romero an unofficial patron saint of the Americas and/or El Salvador; Catholics in El Salvador often refer to him as "San Romero". Outside of Catholicism, Romero is honored by other Christian denominations including Church of England and Anglican Communion through the Calendar in Common Worship, as well as in at least one Lutheran liturgical calendar. Archbishop Romero is also one of the ten 20th-century martyrs depicted in statues above the Great West Door of Westminster Abbey in London. In 2008, Europe-based magazine A Different View included Romero among its 15 Champions of World Democracy.[5]

Early life

Romero was born 15 August 1917[6] to Santos Romero and Guadalupe de Jésus Galdámez in Ciudad Barrios in the San Miguel department of El Salvador.[7] On 11 May 1919, at the age of one, Óscar was baptised into the Catholic Church by Fr. Cecilio Morales.[8] He had 5 brothers and 2 sisters: Gustavo, Zaída, Rómulo, Mamerto, Arnoldo, and Gaspar, and Aminta (who died shortly after birth).[9]

Romero entered the local public school, which offered only grades one through three. When finished with public school, Romero was privately tutored by a teacher, Anita Iglesias,[10] until the age of thirteen.[11] During this time Óscar's father, Santos, trained Romero in carpentry.[12] Romero showed exceptional proficiency as an apprentice. Santos wanted to offer his son the skill of a trade, because in El Salvador studies seldom led to employment.[13] However, the boy broached the idea of studying for the priesthood, which did not surprise those who knew him.[14]

Priesthood

Romero entered the minor seminary in San Miguel at the age of thirteen. He left the seminary for three months to return home when his mother became ill after the birth of her eighth child; during this time he worked with two of his brothers in a gold mine near Ciudad Barrios.[14] After graduation he enrolled in the national seminary in San Salvador. He completed his studies at the Gregorian University in Rome, where he received a Licentiate in Theology cum laude in 1941, but had to wait a year to be ordained because he was younger than the required age.[15] He was ordained in Rome on 4 April 1942.[16] His family could not attend his ordination because of travel restrictions due to World War II.[17] Romero remained in Italy to obtain a doctoral degree in Theology, specializing in ascetical theology and Christian perfection according to Venerable Luis de la Puente.[15] Before finishing, in 1943 at the age of 26, he was summoned back home from Italy by his bishop. He traveled home with a good friend, Father Valladares, who was also doing doctoral work in Rome. On the route home, they made stops in Spain and Cuba, where they were detained by the Cuban police, perhaps for having come from Fascist Italy,[18] and were placed in a series of internment camps. After several months in prison, Valladares became sick and Redemptorist priests helped to have the two transferred to a hospital. From the hospital they were released from Cuban custody and sailed on to Mexico, then traveled overland to El Salvador.[19]

Romero was first assigned to serve as a parish priest in Anamorós, but then moved to San Miguel where he worked for over 20 years.[16] He promoted various apostolic groups, started an Alcoholics Anonymous group, helped in the construction of San Miguel's cathedral, and supported devotion to Our Lady of Peace. He was later appointed rector of the inter-diocesan seminary in San Salvador. Emotionally and physically exhausted by his work in San Miguel, Romero took a retreat in January 1966 where he visited a priest for confession and a psychiatrist. He was diagnosed by the psychiatrist as having obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and by priests with scrupulosity.[20][21]

In 1966, he was chosen to be Secretary of the Bishops Conference for El Salvador. He also became the director of the archdiocesan newspaper Orientación, which became fairly conservative while he was editor, defending the traditional Magisterium of the Catholic Church. In 1970, Romero was appointed an auxiliary bishop for the Archdiocese of San Salvador. In 1974, he was appointed Bishop of the Diocese of Santiago de María, a poor, rural region.[16]

Archbishop

On 23 February 1977, Oscar was appointed Archbishop of San Salvador. While this appointment was welcomed by the government, many priests were disappointed, especially those openly supportive of Marxist ideology. The progressive priests feared that his conservative reputation would negatively affect liberation theology's commitment to the poor.

On 12 March 1977, Rutilio Grande, a Jesuit priest and personal friend of Romero who had been creating self-reliance groups among the poor, was assassinated. His death had a profound impact on Romero, who later stated: "When I looked at Rutilio lying there dead I thought, 'If they have killed him for doing what he did, then I too have to walk the same path.'"[22] Romero urged the government to investigate, but they ignored his request. Furthermore, the censored press remained silent.[23]

Tension was noted by the closure of schools and the lack of Catholic priests invited to participate in government. In response to Grande's murder, Romero revealed an activism that had not been evident earlier, speaking out against poverty, social injustice, assassinations and torture.[24][25]

In 1979, the Revolutionary Government Junta came to power amidst a wave of human rights abuses by paramilitary right-wing groups and the government, in an escalation of violence that would become the Salvadoran Civil War. Romero criticized the United States for giving military aid to the new government and wrote to President Jimmy Carter in February 1980, warning that increased US military aid would "undoubtedly sharpen the injustice and the political repression inflicted on the organized people, whose struggle has often been for their most basic human rights." Carter ignored Romero's pleas and military aid to the Salvadoran government continued.

As a result of his humanitarian efforts, Romero began to be noticed internationally. In February 1980, he was given an honorary doctorate by the University of Louvain. On his visit to Europe to receive this honor, he met Pope John Paul II and expressed his concern at what was happening in his country. Romero argued that it was problematic to support the Salvadoran government because it legitimized terror and assassinations.[23]

Statements on persecution of the Church

| Part of a series on |

| Persecutions of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

Romero denounced the persecution of members of the Catholic Church who had worked on behalf of the poor:[26]

In less than three years, more than fifty priests have been attacked, threatened, calumniated. Six are already martyrs--they were murdered. Some have been tortured and others expelled [from the country]. Nuns have also been persecuted. The archdiocesan radio station and educational institutions that are Catholic or of a Christian inspiration have been attacked, threatened, intimidated, even bombed. Several parish communities have been raided. If all this has happened to persons who are the most evident representatives of the Church, you can guess what has happened to ordinary Christians, to the campesinos, catechists, lay ministers, and to the ecclesial base communities. There have been threats, arrests, tortures, murders, numbering in the hundreds and thousands....

But it is important to note why [the Church] has been persecuted. Not any and every priest has been persecuted, not any and every institution has been attacked. That part of the church has been attacked and persecuted that put itself on the side of the people and went to the people's defense. Here again we find the same key to understanding the persecution of the church: the poor.

— Óscar Romero, Speech at the Université catholique de Louvain, Belgium, 2 February 1980.

Popular radio sermons

By the time of his death, Romero had built up an enormous following among Salvadorans. He did this largely through broadcasting his weekly sermons across El Salvador[27] on the Church's station, YSAX, "except when it was bombed off the air."[28] In these sermons, he listed disappearances, tortures, murders, and much more each Sunday.[27] This was followed by an hour-long speech on radio the following day. On the importance of these broadcasts, one writer noted that "the archbishop's Sunday sermon was the main source in El Salvador about what was happening. It was estimated to have the largest listenership of any programme in the country."[27] According to listener surveys, 73% of the rural population and 37% of the urban listened regularly.[28] Similarly, his diocesan weekly paper Orientación carried lists of cases of torture and repression every week.[27]

Theology

According to Jesús Delgado, his biographer and Postulator of the Cause for his canonization, Romero agreed with the Catholic vision of Liberation Theology and not with the materialist vision: "A journalist once asked him: ‘Do you agree with Liberation Theology’ And Romero answered: "Yes, of course. However, there are two theologies of liberation. One is that which sees liberation only as material liberation. The other is that of Paul VI. I am with Paul VI."[29] Delgado said that Romero did not read the books on Liberation Theology which he received, and he gave the lowest priority to Liberation Theology among the topics that he studied.[30]

Romero preached that "The most profound social revolution is the serious, supernatural, interior reform of a Christian."[31] He also emphasized: "The liberation of Christ and of His Church is not reduced to the dimension of a purely temporal project. It does not reduce its objectives to an anthropocentric perspective: to a material well-being or only to initiatives of a political or social, economic or cultural order. Much less can it be a liberation that supports or is supported by violence."[32][33] Romero expressed several times his disapproval for divisiveness in the Church. In a sermon preached on 11 November 1979 he said: "The other day, one of the persons who proclaims liberation in a political sense was asked: ‘For you, what is the meaning of the Church’?" He said that the activist "answered with these scandalous words: ‘There are two churches, the church of the rich and the church of the poor. We believe in the church of the poor but not in the church of the rich.’" Romero declared, "Clearly these words are a form of demagogy and I will never admit a division of the Church." He added, "There is only one Church, the Church that Christ preached, the Church to which we should give our whole hearts. ...There is only one Church, a Church that adores the living God and knows how to give relative value to the goods of this earth."[34]

Spiritual life

Romero noted in his diary on 4 February 1943: "In recent days the Lord has inspired in me a great desire for holiness. I have been thinking of how far a soul can ascend if it lets itself be possessed entirely by God." Commenting on this passage, James R. Brockman, S.J., Romero's biographer and author of Romero: A Life, said that "All the evidence available indicates that he continued on his quest for holiness until the end of his life. But he also matured in that quest."[35]

According to Brockman, Romero's spiritual journey had some of these characteristics:

- love for the Church of Rome, shown by his episcopal motto, "to be of one mind with the Church," a phrase he took from St. Ignatius' Spiritual Exercises;

- a tendency to make a very deep examination of conscience;

- an emphasis on sincere piety;

- mortification and penance through his duties;

- providing protection for his chastity;

- spiritual direction;

- "being one with the Church incarnated in this people which stands in need of liberation";

- eagerness for contemplative prayer and finding God in others;

- fidelity to the will of God;

- self-offering to Jesus Christ.

Romero was a strong advocate of the spiritual charism of Opus Dei. He received weekly spiritual direction from a priest of the Opus Dei movement.[36] In 1975 he wrote in support of the cause of canonization of Opus Dei's founder, "Personally, I owe deep gratitude to the priests involved with the Work, to whom I have entrusted with much satisfaction the spiritual direction of my own life and that of other priests."[37][38]

Martyrdom

On 23 March 1980, Romero delivered a sermon in which he called on Salvadoran soldiers, as Christians, to obey God's higher order and to stop carrying out the government's repression and violations of basic human rights.[40]

Romero spent 24 March in a recollection organized by Opus Dei,[41] a monthly gathering of priest friends led by Msgr. Fernando Sáenz Lacalle. On that day they reflected on the priesthood.[42] That evening, Romero celebrated Mass[43][44] at a small chapel at Hospital de la Divina Providencia (Divine Providence Hospital).[45] (a church-run hospital specializing in oncology and care for the terminally ill).[46] Romero finished his sermon, stepped away from the lectern, and took a few steps to stand at the center of the altar.[40]

As Romero finished speaking, a red automobile came to a stop on the street in front of the chapel. The gunman emerged from the vehicle, stepped to the door of the chapel, and fired one (possibly two) shots at Romero, probably using a silencer. Romero was struck in the heart, and the vehicle sped off.[45]

Funeral

Romero was buried in the Metropolitan Cathedral of San Salvador (Catedral Metropolitana de San Salvador). The Funeral Mass on 30 March 1980 in San Salvador was attended by more than 250,000 mourners from all over the world. Viewing this attendance as a protest, Jesuit priest John Dear has said, "Romero's funeral was the largest demonstration in Salvadoran history, some say in the history of Latin America."

At the funeral, Cardinal Ernesto Corripio y Ahumada, speaking as the personal delegate of Pope John Paul II, eulogized Romero as a "beloved, peacemaking man of God," and stated that "his blood will give fruit to brotherhood, love and peace."[47]

Massacre at Romero's funeral

During the ceremony, smoke bombs exploded on the streets near the cathedral and subsequently there were rifle shots that came from surrounding buildings, including the National Palace. Many people were killed by gunfire and in the stampede of people running away from the explosions and gunfire; official sources reported 31 overall casualties, while journalists recorded that between 30 and 50 died.[48] Some witnesses claimed it was government security forces that threw bombs into the crowd, and army sharpshooters, dressed as civilians, that fired into the chaos from the balcony or roof of the National Palace. However, there are contradictory accounts as to the course of the events and "probably, one will never know the truth about the interrupted funeral."[48]

As the gunfire continued, Romero's body was buried in a crypt beneath the sanctuary. Even after the burial, people continued to line up to pay homage to their martyred prelate.[17][49][50][51]

International reaction

Ireland

All sections of Irish political and religious life condemned his assassination, with the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs Brian Lenihan "expressing shock and revulsion at the murder of Dr Romero,"[52] while the leader of the Trócaire charity, Eamon Casey, revealed that he had received a letter from Romero that very day.[53] The previous October parliamentarians had given their support to the nomination that Archbishop Romero receive the Nobel Prize for Peace.[53] In March each year since the 1980s, the Irish-El Salvador Support Committee holds a mass in honour of Archbishop Romero.[54]

United Kingdom

In October 1978, 119 British parliamentarians nominated Romero for the Nobel Prize for Peace. In this they were supported by 26 members of the United States Congress.[27] When news of his assassination was reported, the new head of the Church of England, Robert Runcie, was about to be enthroned in Canterbury Cathedral. On hearing of Romero's death, one writer observed that Runcie "departed from the ancient traditions to decry the murder of Archbishop Oscar Romero in El Salvador."[55]

Investigations into the assassination

To date, no one has ever been prosecuted for the assassination, or confessed to it. The assassin has not been identified.[56]

It is widely believed that the four assassins were members of a death squad led by former Major Roberto D'Aubuisson.[57] This view was supported by ex-US ambassador Robert White, who in 1984 reported to the United States Congress that "there was sufficient evidence" to convict D'Aubuisson of planning and ordering Archbishop Romero's assassination.[58] It was also supported in 1993 by an official United Nations report which identified D'Aubuisson as the man who ordered the killing.[48] It is believed that D'aubisson had strong connections to the Nicaraguan National Guard and to its offshoot the Fifteenth of September Legion[59] and had also planned to overthrow the government in a coup. Later he founded the political party Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA), and organized death squads that systematically carried out politically motivated assassinations and other human rights abuses in El Salvador. Álvaro Rafael Saravia, a former captain in the Salvadoran Air Force, was chief of security for D'Aubuisson and an active member of these death squads. In 2003 a United States human rights organization, the Center for Justice and Accountability, filed a civil action against Saravia. In 2004, he was found liable by a US District Court under the Alien Tort Claims Act (ATCA) (28 U.S.C. § 1350) for aiding, conspiring, and participating in the assassination of Romero. Saravia was ordered to pay $10 million for extrajudicial killing and crimes against humanity pursuant to the ATCA;[60] he has since gone into hiding.[61] On 24 March 2010 – the thirtieth anniversary of Romero's death – Salvadoran president Mauricio Funes offered an official state apology for Romero's assassination. Speaking before Romero's family, representatives of the Catholic Church, diplomats, and government officials, Funes said those involved in the assassination "…unfortunately acted with the protection, collaboration, or participation of state agents."[62]

A 2000 article by then-UK's Guardian, later BBC, correspondent Tom Gibb attributes the murder to a detective of the Salvadoran National Police named Oscar Perez Linares, on orders of D'Aubuisson. The article cites an anonymous former death squad member who claimed he had been assigned to guard a house in San Salvador used by a unit of 3 counter-guerrilla operatives directed by D'Aubuisson. The guard, who Gibb identified as "Jorge," purported to have witnessed Linares fraternizing with the group, which was nicknamed the "Little Angels," and to have heard them praise Linares for the killing. The article furthermore attributes full knowledge of the assassination to the CIA as far back as 1983.[57] The article reports that both Linares and the Little Angels commander, who Jorge identified as "El Negro Mario," were killed by a CIA-trained Salvadoran special police unit in 1986; the unit had been assigned to investigate the murders. In 1983, Lt. Col. Oliver North, aide to then-Vice President George H.W. Bush, is alleged to have personally requested the Salvadoran military to "remove" Linares and several others from their service. Three years later they were pursued and extrajudicially killed – Linares after being found in neighboring Guatemala. The article cites another source in the Salvadoran military as saying, "they knew far too much to live."[63]

In a 2010 article for the El Salvador online newspaper article El Faro,[56] Saravia, who was interviewed from a mountain hideout,[56] named D'Aubuisson as giving the assassination order to him over the phone.[56][64] Saravia said that he and his cohorts drove the assassin to the chapel and paid him 1,000 Salvadoran colons after the event.[56]

Legacy

International recognition

During his first visit to El Salvador in 1983, Pope John Paul II entered the cathedral in San Salvador and prayed at Romero's tomb, despite opposition from the government and from some within the Church who strongly opposed Liberation Theology. Afterwards, the Pope praised Romero as a "zealous and venerated pastor who tried to stop violence." John Paul II also asked for dialogue between the government and opposition to end El Salvador's civil war.[65]

On 7 May 2000, in Rome's Colosseum during the Jubilee Year celebrations, Pope John Paul II commemorated twentieth-century martyrs. Of the several categories of martyrs, the seventh consisted of Christians who were killed for defending their brethren in the Americas. Despite the opposition of some social conservatives within the Church, John Paul II insisted that Archbishop Romero be included. He asked the organizers of the event to proclaim Romero "that great witness of the Gospel."[66]

On 21 December 2010, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 24 March as the International Day for the Right to the Truth concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims which recognizes, in particular, the important work and values of Archbishop Óscar Arnulfo Romero.[67][68]

On 22 March 2011, U.S. President Barack Obama visited Romero's tomb during an official visit to El Salvador.[69]

President of Ireland Michael D. Higgins visited the Cathedral and tomb of Archbishop Romero on 25 October 2013 during a state visit to El Salvador.[70][71] Famed linguist Noam Chomsky speaks highly and often about Romero's social work and murder[72]

Sainthood

Process for beatification

In 1990, on the tenth anniversary of the assassination, the sitting Archbishop of San Salvador, Arturo Rivera y Damas, appointed a postulator to prepare documentation for a cause of beatification and eventual canonization of Romero. The documents were formally accepted by Pope John Paul II and the Congregation for the Causes of Saints in 1997, and Romero was given the title of Servant of God.

In March 2005, Vincenzo Paglia, the Vatican official in charge of the process, announced that Romero's cause had cleared a theological audit by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, at the time headed by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later elected Pope Benedict XVI) and that beatification could follow within six months.[73] Pope John Paul II died within weeks of those remarks. Predictably, the transition of the new pontiff slowed down the work of canonizations and beatifications. Pope Benedict instituted changes that had the overall effect of reining in the Vatican's so-called "factory of saints."[74] In an October 2005 interview, Cardinal Jose Saraiva Martins, the Prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, was asked if Paglia's predictions of a clearance for Romero's beatification remained on track. Cardinal Saraiva responded, "Not as far as I know today,"[75] In November 2005, a Jesuit magazine signaled that Romero's beatification was still "years away."[76]

Then in December 2012 Paglia said that Benedict XVI had informed him that he had decided to "unblock" the cause and allow it to move forward.[77] In 2013, Archbishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller, Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, stated that the Vatican doctrinal office has been "given the greenlight" to pursue sainthood for Romero.[78] In 2014, Gregorio Rosa Chávez, Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of San Salvador, said that the beatification process was in its final stages.[79]

Basis for canonization

The Congregation for Saints' Causes voted unanimously to recommend Pope Francis recognize Romero as a martyr. "He was killed at the altar. Through him, they wanted to strike the church that flowed from the Second Vatican Council." His assassination "was not caused by motives that were simply political, but by hatred for a faith that, imbued with charity, would not be silent in the face of the injustices that relentlessly and cruelly slaughtered the poor and their defenders."[77]

On Monday, 19 May 2014, an online news story article appearing on the Catholic News Service (CNS) website homepage stated that the incumbent Archbishop of San Salvador, José Luis Escobar Alas, and three other Salvadoran Catholic bishops, meeting with Pope Francis, urged him to come to San Salvador to personally beatify Archbishop Romero if and when he is beatified.

To be beatified, a posthumous, usually an unexplainable medical miracle (verified by the prelate members of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints after an archdiocesan and Vatican-based medical and theological investigation, and signed by the Pope) would need to be attributed to an intercession to him, or alternatively, he could be declared a martyr or the Pope could, extremely rarely, use his right to waive both of these requirements for beatification, which, somewhat like canonization is meant to be a definitive statement about his sanctity. The controversy was whether his assassination was solely out of hatred for the faith (the requirement for martyrdom), or was influenced by politics, liberation theology, or by his vocal criticisms of the regime at the time during the civil war.[80]

Beatification

On 18 August 2014, Pope Francis said that "[t]he process [of beatification of Romero] was at the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, blocked for 'prudential reasons', so they said. Now it is unblocked." Pope Francis stated that "There are no doctrinal problems and it is very important that [the beatification] is done quickly."[81][82][83] The beatification is widely seen as the pope's strong affirmation of Romero's work with the poor and as a major change in the direction of the church since he was elected.[84]

On Friday, 9 January 2015, an online news story article by Carol Glatz of Catholic News Service (CNS) stated that on Thursday, 8 January 2015: "A panel of theologians advising the Vatican's Congregation for the Causes of Saints voted unanimously to recognize the late Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero as a martyr, according to the newspaper of the Italian bishops' conference." It is a key step in his canonization process. Next, the Cardinals who are voting members of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints in the Roman Curia must vote to recommend to Pope Francis that Archbishop Romero be beatified. A miracle is not required for beatification candidates who the Pope decrees are martyrs to be beatified, as it would normally be otherwise. If he is beatified as a martyr, a miracle will then normally be needed for him to be canonized.[85]

On Tuesday, 3 February 2015, Pope Francis received Cardinal Angelo Amato, S.D.B., Prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, in a private audience, and authorized the Cardinal to promulgate (officially authorize) Archbishop Romero's decree of martyrdom, meaning it had gained the Congregation's voting members and the Pope's approval. This cleared the way for the Pope to later set a date for his beatification.[86]

The beatification of Romero was held in San Salvador on 23 May 2015 in the Plaza Salvador del Mundo under the Monumento al Divino Salvador del Mundo. Cardinal Angelo Amato presided over the ceremony on behalf of Pope Francis, who sent a letter to Archbishop of San Salvador José Luis Escobar Alas, marking the occasion and calling Romero "a voice that continues to resonate."[87] An estimated 250,000 people attended the service,[88] many watching on large television screens set up in the streets around the plaza.[89]

Canonization

Three miracles were submitted to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints in Rome in October 2016 that could have led to Romero's canonization. But each of these miracles were rejected after being investigated. A fourth (concerning the pregnant woman Cecilia Maribel Flores) was investigated in a diocesan process in San Salvador which concluded its initial investigation on 28 February 2017 before documentation was submitted to Rome via the apostolic nunciature.[90]

There were hopes that Romero would be canonized during a possible papal visit to El Salvador on 15 August 2017 – the centennial of the late bishop's birth. There have been other hopes that Romero could be canonized in Panama during World Youth Day in 2019.[91]

In popular culture

Institutions

- The Romero Centre in Dublin is today an important centre that "promotes Development Education, Arts, Crafts, and Awareness about El Salvador."[92]

- The Christian Initiative Romero is a non-profit organisation in Germany working in support of industrial law and human rights in Central American countries.[93]

- The Romero Institute, a nonprofit law and public policy center in Santa Cruz, California, headed by Daniel Sheehan, was named after Archbishop Romero in 1996.[94]

- Edmonton Catholic School System named in 2004 a High School in west Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, Archbishop Oscar Romero High School.

- A secondary school in the town of Hoorn, The Netherlands, is named after Archbishop Oscar Romero.

- The Toronto Catholic District School Board opened in 1989 a secondary school in Toronto, Canada, named after Archbishop Oscar Romero.[95]

Television and film

- The film Romero (1989) was based on the Archbishop's life story. It was directed by John Duigan and starred Raúl Juliá. It was produced by Paulist Productions (a film company run by the Paulist Fathers, a Roman Catholic society of priests). Timed for release ten years after Romero's death, it was the first Hollywood feature film ever to be financed by the order. The film received respectful, if less-than-enthusiastic, reviews. Roger Ebert typified the critics who acknowledged that "The film has a good heart, and the Juliá performance is an interesting one, restrained and considered. ...The film's weakness is a certain implacable predictability."[96]

- Oliver Stone's 1986 film, Salvador, contains a dramatisation of the assassination of Archbishop Romero (played in the movie by José Carlos Ruiz). The film tells the story of photojournalist Richard Boyle (James Woods) who undergoes a spiritual conversion while covering the death squad killings in El Salvador during the Civil War.

- Romero was also featured in the made-for-TV movie Choices of the Heart (NBC, 1983, René Enríquez as Romero) about the murder of four U.S. churchwomen in El Salvador.

- Romero was depicted in two biopics about Pope John Paul II, the U.S. television biopic Have No Fear: The Life of Pope John Paul II (ABC, 2005, Joaquim de Almeida as Romero) and the Italian biopic Karol, una papa rimasto uomo (English translation for Canadian TV Karol: The Pope, The Man) 2006, Carlos Kaniowsky as Romero.

- In 2005, while at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, Daniel Freed,[97] an independent documentary filmmaker and frequent contributor to PBS and CNBC, made a 30-minute film entitled The Murder of Monseñor[98] which not only documented Romero's assassination but also told the story of how Álvaro Rafael Saravia – whom a US District court found, in 2004, had personally organized the assassination – moved to the United States and lived for 25 years as a used car salesman in Modesto, California, until he became aware of the pending legal action against him in 2003 and disappeared, leaving behind his drivers license and social security card, as well as his credit cards and his dog.

- The Daily Show episode on 17 March 2010 showed clips from the Texas State Board of Education in which "a panel of experts" recommended including Romero in the state's history books,[99] but an amendment proposed by Patricia Hardy[100] to exclude Romero was passed on 10 March 2010. The clip of Ms. Hardy shows her arguing against including Romero because "I guarantee you most of you did not know who Oscar Romero was. ...I just happen to think it's not [important]." Romero has also had a house at Cardijn College named after him.

- A film about the Archbishop, Monseñor, the Last Journey of Óscar Romero, with Father Robert Pelton, C.S.C., serving as executive producer, had its United States premiere in 2010. This film won the Latin American Studies Association (LASA) Award for Merit in film, in competition with 25 other films. Father Pelton was invited to show the film throughout Cuba. It was sponsored by ecclesial and human rights groups from Latin America and from North America.[101] Alma Guillermoprieto in The New York Review of Books describes the film as a "hagiography," and as "an astonishing compilation of footage" of the final three years of his life.[102]

Visual arts

- John Roberts sculpted a statue of Óscar Romero that fills a prominent niche on the western facade of Westminster Abbey in London; it was unveiled in the presence of Queen Elizabeth II in 1998.[103] Barry Woods Johnston sculpted a statue of Óscar Romero displayed in the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. Italian sculptor Paolo Borghi crafted the catafalque that covers Romero's tomb in the crypt of the San Salvador cathedral and shows Romero "sleeping the sleep of the just" as four Evangelists stand guard.

- Brother Robert Lentz, O.F.M., painted a now-famous icon of Archbishop Romero based on traditional Church iconography but with updated conventional elements; for example, the traditional angels are replaced with military helicopters over red tiled roofs. Frank Diaz Escalet executed a series of "outsider art" paintings of Archbishop Romero, now exhibited in the permanent collection of the Organization of American States Museum in Washington, D.C., in the permanent collection of the Art Museum of Southeast Texas, Beaumont, Texas, in the Ella Noel Museum of Odessa, Texas, and in the Maryknoll Galleries in Ossining, New York.

- Bishop Romero is depicted in a 1998 painting by Puerto Rican artist Frank Diaz Escalet, entitled, ""Oscar Romero, Unregalo De Dios Para El Mundo Entero," a work painted with acrylic on a masonite panel. The English translation of the title is "“Oscar Romero, a gift from God for the whole world.” The painting depicts a haloed Bishop Romero, dressed in a simple white alb, cradling the Earth in his left hand and attended by flower-bearing, winged angels. The painting is now in a private collection in Sacramento, California.

Poetry and song

- The most famous reference to Romero's death in Spanish-language songs is "El Padre Antonio y su Monaguillo Andrés" ("Father Anthony and Acolyte Andrew"), written and sung by Panamanian Rubén Blades. This song describes the arrival in a Latin American country of an idealistic Spanish priest (a fictional representation of Archbishop Romero), his sermons condemning violence there, his talks about love and justice, and, finally, the murders of the priest and acolyte during a Mass.[104] Blades has said he wrote this song so that "the death of Romero is not forgotten."[citation needed]

- In 1981, Brazilian classical composer Jorge Antunes wrote a choral-symphonic work entitled "Elegia Violeta para Monsenhor Romero" ("Violet Elegy for Monsignor Romero") using texts from Che Guevara, Vassili Vassilikos, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Psalms, and Archbishop Romero himself as lyrics. The work finishes with the children's choir repeating, each time more strongly, "¡No se mata la justicia!" ("Justice cannot be killed!": the very words in which Archbishop Romero replied to a Brazilian reporter's question whether the archbishop was afraid he'd be killed because of his defense of the poor and his protest against the murders of priests) – until their voices are muted by seemingly panicked, syncopated instrumental sounds.

- Brazilian Bishop Dom Pedro Casaldáliga immortalized Romero as "San Romero de América" ("Saint Romero of the Americas") in a famous poem by that name written shortly after the archbishop's assassination. The poem, a variation on the Angelus, popularized the use of the phrase "San Romero" (instead of "Saint Oscar") throughout Latin America (and, for example, in Escalet's "San Romero" paintings or in the "San Romero de América" UCC Church in New York City).

- Welsh singer-songwriter Dafydd Iwan wrote about Romero's assassination in the song "Oscar Romero".[105]

- "Eulogy For Oscar Romero" is an instrumental piece composed and performed by Jean-Luc Ponty.

- "The Marching Song of the Covert Battalions," the third track on Billy Bragg's 1990 album The Internationale, pays homage to Romero.

- Romero is mentioned in the song "Same Thing" by the American alternative hip hop band Flobots.

- The British songwriter/preacher Garth Hewitt recorded a song about Oscar Romero on his 1985 Alien Brain album.

- The 2012 special event album "Martyrs Prayers" by The Project contains a track called "Romero" with lyrics consisting entirely of Óscar Romero's documented prayers. The accompaniment short film for the song uses footage issued by The University Of Notre Dame, stewards of the documentary footage for Monseñor: The Last Journey Of Óscar Romero.[106]

- Christy Moore mentions Archbishop Romero in his song "Casey".[107]

- Singer/songwriter Josh Ritter references Romero in his song "Harrisburg".

Literature

In their work Manufacturing Consent, Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman used the murders of Romero and other Latin American clergy, and their subsequent media coverage in the United States, as a case study of the propaganda model, where it is compared and contrasted with the coverage of the murder of Catholic priest Jerzy Popiełuszko in Communist Poland. Chomsky and Herman argued that being murdered by an enemy state, Popiełuszko would be seen as a "worthy victim" and thus receive extensive press coverage, while Romero and other Latin American clergy, being murdered by US client states, would be deemed as "unworthy victims", and thus would not receive as much press coverage.[108]

See also

Ordination history of Óscar Romero | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

Catholic priests assassinated in El Salvador during and after Óscar Romero's time as archbishop (1977–1980):

- Rutilio Grande, S.J.: assassinated 12 March 1977;

- Alfonso Navarro: assassinated 11 May 1977;

- Ernesto Barrera: assassinated 28 November 1978;

- Octavio Ortiz: assassinated 20 January 1979;

- Rafael Palacios: assassinated 20 June 1979;

- Napoleón Macías: assassinated 4 August 1979;

- Ignacio Martín-Baró, S.J.: assassinated 16 November 1989;

- Joaquín López y López, S.J.: assassinated 16 November 1989;

- Juan Ramón Moreno, S.J.: assassinated 16 November 1989;

- Segundo Montes, S.J.: assassinated 16 November 1989;

- Ignacio Ellacuría, S.J.: assassinated 16 November 1989;

- Amando López, S.J.: assassinated 16 November 1989.

Murder of U.S. missionaries in El Salvador on 2 December 1980: three Religious Sisters and one lay worker:

- Maura Clarke, Maryknoll

- Jean Donovan, lay missionary

- Ita Ford, M.M.

- Dorothy Kazel, Ursulines

References

- ^ "Oscar Romero, patron of Christian communicators? (in Spanish)". Aleteia. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "Romero co-patrono di Caritas Internationalis". Avvenire. 16 May 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Pope Francis sends letter for the beatification of Óscar Romero".

- ^ "Archbishop Romero had no interest in liberation theology, says secretary".

- ^ A Different View, Issue 19, January 2008.

- ^ Edward S. Mihalkanin; Robert F. Gorman (2009). The A to Z of Human Rights and Humanitarian Organizations. Scarecrow Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0810868748 – via books.google.com.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mario Bencastro; Arte Público Press (1996). A Shot in the Cathedral. books.google.com. p. 182. ISBN 978-1558851641.

- ^ James R. Brockman (1989). Romero: A Life. Orbis Books. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-88344-652-2.

The child was almost two years old before he was baptized in the church across the square by Father Cecilio Morales.

- ^ James R. Brockman (2005). Romero: A Life. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-57075-599-6.

Her first child was Gustavo, Oscar Arnulfo her second. Then followed Zaida, Rómulo (who died in 1939, while Oscar was studying in Rome), Mamerto, Arnoldo, and Gaspar. A daughter, Aminta, died at birth. Their father also had at least one illegitimate child, a daughter, who still lived in Ciudad Barrios at the time of Oscar Romero's death.

- ^ James R. Brockman (1982). The Word Remains: A Life of Oscar Romero. Orbis Books. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-88344-364-4.

- ^ James R. Brockman (2005). Romero: A Life. Orbis Books. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-57075-599-6.

The office was in the Romero home on the plaza, and the Romero children delivered letters and telegrams in the town. ... After that his parents sent him to study under a teacher named Anita Iglesias until he was twelve or thirteen.

- ^ Robert Royal (2000). The Catholic martyrs of the twentieth century: a comprehensive world history. Crossroad Pub. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-8245-1846-2.

- ^ Wright, Scott (26 February 2015). "Family". Oscar Romero and the Communion of Saints: A Biography. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-60833-247-2. "Most children never had the opportunity or the means to even consider [a vocation such as the priesthood]. At least that was his father's belief, and for that reason, he sent his son to learn a trade." Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ a b Adams, Jerome R. (2010). "Liberators, Patriots and Leaders of Latin America: 32 Biographies". McFarland & Company, Inc. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Wright, Scott (26 February 2015). "Family". Oscar Romero and the Communion of Saints: A Biography. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-60833-247-2. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ a b c "Biography of Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero - International Day for the Right to the Truth Concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims, 24 March".

- ^ a b "Romero biography" (PDF). Kellogg Institute, Notre Dame University. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ Italy had signed an armistice with the Allies two weeks earlier, but the ship on which they sailed had recently been suspected of espionage. Mort, Terry (2009). "The Hemingway Patrols: Ernest Hemingway and His Hunt for U-Boats". Scribner. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ "Oscar Romero's Odyssey in Cuba". Supermartyrio: The Martyrdom Files. December 21, 2015. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ Clarke, Kevin (2014). Oscar Romero: Love Must Win Out. Liturgical Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-8146-3757-9.

- ^ Schaller, George (2011). Congregants Of Silence. Lulu. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-105-19762-8.

- ^ Michael A. Hayes (Chaplain); Tombs, David (April 2001). "Truth and memory: the Church and human rights in El Salvador and Guatemala". Gracewing Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85244-524-2.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help). - ^ a b "infed.org - Oscar Romero of El Salvador: informal adult education in a context of violence". infed.org.

- ^ Eaton, Helen-May (1991). The impact of the Archbishop Oscar Romero's alliance with the struggle for liberation of the Salvadoran people: A discussion of church-state relations (El Salvador) (M.A. thesis) Wilfrid Laurier University

- ^ Michael A. Hayes (Chaplain); Tombs, David (April 2001). "Truth and memory: the Church and human rights in El Salvador and Guatemala". Gracewing Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85244-524-2.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help). - ^ Oscar Romero, Voice of the Voiceless: The Four Pastoral Letters and Other Statements (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1985), pp. 177-187.

- ^ a b c d e Peadar Kirby, 'A Thoroughgoing Reformer', 26 March 1980, The Irish Times

- ^ a b A Shepherd's Diary, Foreword.

- ^ "Archbishop Oscar Romero: Pastor and Martyr – ZENIT – English". Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ .Jesús DELGADO, "La cultura de monseñor Romero," [Archbishop Romero’s Culture] in Óscar Romero un Obispo entre la guerra fría y la revolución, Editorial San Pablo, Madrid, 2003.

- ^ O. A. Romero, La Más Profunda Revolución Social [The Most Profound Social Revolution], DIARIO DE ORIENTE, No. 30867 – p. 1, August 28, 1973.

- ^ 6 August 1976 Sermon

- ^ "Adital - Comblin: Bastão de Deus que fustiga os acomodados".

- ^ Three Christian Forces for Liberation, 11 November 1979 Sermon

- ^ James Brockman, S.J. "The Spiritual Journey of Oscar Romero". Spirituality Today. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ "Pope declares Oscar Romero, hero to liberation theology, a martyr". 3 February 2015.

- ^ "Opus Dei - Oscar Romero". Retrieved 2015-01-15.

- ^ "Archbishop Oscar Romero: Letter to the Pope on Escriva's death". 5 February 2015.

- ^ Ediciones El País. "El Salvador hace justicia a monseñor Óscar Romero". EL PAÍS.

- ^ a b Julian Miglierini (24 March 2010). "El Salvador marks Archbishop Oscar Romero's murder". BBC News.

- ^ "Oscar Romero and St. Josemaria".

- ^ "The final hours of Monsignor Romero".

- ^ Mayra Gómez (2 October 2003). Human Rights in Cuba, El Salvador, and Nicaragua: A Sociological Perspective on Human Rights Abuse. Taylor & Francis. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-415-94649-0.

The following day, Archbishop Oscar Romero was shot dead in front of a full congregation as he was delivering mass (AI ...

- ^ Henry Settimba (1 March 2009). Testing Times: Globalisation and Investing Theology in East Africa. AuthorHouse. p. 223. ISBN 978-1-4678-9899-7.

- ^ a b "Salvador Archbishop Assassinated By Sniper While Officiating at Mass". The New York Times. March 25, 1980. pp. 1, 8.

- ^ "Salvadoran Archbishop Assassinated". The Washington Post. March 25, 1980. pp. A1, A12.

- ^ "El Salvador: Something Vile in This Land". Time Magazine. April 14, 1980. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- ^ a b c Morozzo p. 351-2, 354, 364

- ^ "Chronology" (PDF). Chronology of the Salvadoran Civil War, Kellogg Institute, University of Notre Dame. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ Walsh, Maurice (March 23, 2005). "Requiem for Romero". BBC News. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ Christopher Dickey. "40 Killed in San Salvador: 40 Killed at Rites For Slain Prelate; Bombs, Bullets Disrupt Archbishop's Funeral". Washington Post Foreign Service. pp. A1. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ 'Three ministers flee El Salvador, 29 March 1980

- ^ a b 'Romero letter received on day of killing;, 26 March 1980, The Irish Times

- ^ 'Permission given for Romero mass', 30 March 2007, The Irish Times

- ^ 'Runcie urges charity', 26 March 1980, The Irish Times

- ^ a b c d e O'Connor, Anne-Marie (6 April 2010). "Participant in 1980 assassination of Romero in El Salvador provides new details" – via washingtonpost.com.

- ^ a b

"The killing of Archbishop Oscar Romero was one of the most notorious crimes of the cold war. Was the CIA to blame?". The Guardian. 2000-03-22. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

in mid-1983, an unusually detailed CIA report, quoting a senior Salvadoran police source, named Linares as a member of a four-man National Police squad which murdered Romero. Other Salvadoran officers said the same thing. And the man who drove the car which took the killer to the church also picked out a photo-fit of Linares."

- ^ Nordland, Rod (March 23, 1984), "How 2 rose to vie for El Salvador's presidency", Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, PA, p. A1

- ^ Webb, Gary (1999). Dark Alliance. Seven Stories Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-888363-93-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Doe v. Rafael Saravia, 348 F. Supp. 2d 1112 (E.D. Cal. 2004). The documentation from the case provides an account of the events leading up, and subsequent, to Archbishop Romero's death.

- ^ "Doe v. Saravia - CJA".

- ^

"Official El Salvador apology for Oscar Romero's murder". BBC News. 2010-03-25. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

The archbishop, he said, was a victim of right-wing death squads "who unfortunately acted with the protection, collaboration or participation of state agents."

- ^ Gibb, Tom (22 March 2000). "The killing of Archbishop Oscar Romero was one of the most notorious crimes of the cold war. Was the CIA to blame?" – via The Guardian.

- ^ Anne-Marie O'Connor. "Participant in 1980 assassination of Romero in El Salvador provides new details" Washington Post, 6 April 2010.

- ^

Paul D. Newpower, M.M.; Stephen T. DeMott, M.M. (June 1983). ":"Pope John Paul II in Central America: What Did His Trip Accomplish?"". St. Anthony Messenger. United States. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

The pontiff went on to proclaim Archbishop Romero as "a zealous and venerated pastor who tried to stop violence. I ask that his memory be always respected, and let no ideological interest try to distort his sacrifice as a pastor given over to his flock." The right-wing groups did not want to hear that. They portray Romero as one who stirred the poor to violence. The other papal gesture that drew diverse reactions in El Salvador and rankled the Reagan administration was the pope's use of the word dialogue in talking about steps toward ending the civil war. A month before John Paul II journeyed to Central America, U.S. government representatives visited the Vatican and El Salvador to persuade Church officials to have the pope mention elections rather than dialogue.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Dziwisz, Stanislaw Life with Karol: My Forty-Year Friendship with the Man Who Became Pope , p. 217-218, Doubleday Religion, 2008 ISBN 0385523742

- ^ "International Day for the Right to the Truth Concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims, 24 March". www.un.org. United Nations. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ "International Day for the Right to the Truth Concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims, 24 March". www.un.org. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- ^

"Obama en El Salvador: una visita cargada de simbolismo". BBC MUNDO. 2011-03-22. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

El Salvador fue la etapa más llena de simbolismo de la gira por América Latina del presidente de Estados Unidos, Barack Obama.

- ^ Coinní Poiblí ag an Uachtarán Mícheál D. Ó hUigínn don tseachtain dar tús 21 Deireadh Fómhair, 2013 Áras an Uachtaráin, 2013-10-21.

- ^ President Higgins visits Archbishop Romero's tomb in El Salvador RTÉ News, 2013-10-26.

- ^ "Chomsky on Romero - Commonweal Magazine".

- ^ "Catholic World News : Beatification cause advanced for Archbishop Romero". Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ "Will the Pope ever make fewer saints?". Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ "30Days - Blessed among their people, Interview with Cardinal José Saraiva Martins". Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ "CNS STORY: Magazine says Archbishop Romero was killed for actions of faith". Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ a b "Catholic News Service".

- ^ Hafiz, Yasmine (10 September 2013). "Welcome Back Liberation Theology". Huffington Post.

- ^ "Prensa Latina News Agency".

- ^ "CBishops ask pope to beatify Archbishop Romero in El Salvador".

- ^ "BBC News - Pope lifts beatification ban on Salvadoran Oscar Romero". BBC News.

- ^ "Romero's beatification cause was "unblocked" by two Popes".

- ^ "In-Flight Press Conference of His Holiness Pope Francis from Korea to Rome (18 August 2014)".

- ^ Kington, Tracy Wilkinson, Tom. "Romero beatification signals Pope Francis' plan for Catholic Church".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Panel advising Vatican unanimous that Archbishop Romero is a martyr". catholicnews.com. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2015/02/03/0089/00190.html - Translator".

- ^ elsalvador.com. "404 - Página no encontrada".

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "Oscar Romero beatification draws huge El Salvador crowds". BBC News. 23 May 2015.

- ^ Kahn, Carrie (25 May 2015). "El Salvador's Slain Archbishop Romero Moves A Step Closer To Sainthood". NPR News.

- ^ "Vatican to study possible miracle by slain Archbishop Oscar Romero". Crux. 6 March 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Metalli, Alver (17 March 2017). "Romero santo, ma quando?". La Stampa. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ "Romero".

- ^ "About us". Christliche Initiative Romero e.V. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ http://romeroinstitute.org/about-us/our-name

- ^ "About us". Archbishop Romero Catholic Secondary School. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ Roger Ebert (8 September 1989). "Romero".

- ^ Freed, Daniel. "About Daniel Freed". The "About" page. The Daniel Freed website. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Freed, Daniel. "The Murder of Monseñor". A 30-minute documentary film (2005). The Daniel Freed Website. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/teks/social/AlphabetizedList_such_as.pdf

- ^ "SBOE Member District 11".

- ^ "Romero Days 24–29 March 2010". Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ Guillermoprieto, Alma (27 May 2010). "Death Comes for the Archbishop". The New York Review of Books. LVII (9): 41–2. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ "Westminster Abbey: Oscar Romero". Retrieved 2011-03-20.

- ^ ""El Padre Antonio y el Monaguillo Andrés" de Rubén Blades // #MúsicaEnProDaVinci « Prodavinci". prodavinci.com (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- ^ James, E. Wyn (2005). "Painting the World Green: Dafydd Iwan and the Welsh Protest Ballad". Folk Music Journal. 8 (5): 594–618.

- ^ "THE PROJECT: MARTYRS PRAYERS - THE OFFICIAL WEBSITE". themartyrsproject.com. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Casey - Christy Moore". Christy Moore.

- ^ Herman, Edward; Chomsky, Noam (2002). Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (2nd ed.). Pantheon Books. p. 37. ISBN 0375714499.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- his page on the Catholic Hierarchy website

- [1] the official website for Archbishop Romero's cause for beatification (scheduled for May 23, 2015)]

- the Romero Trust

- ctu.edu, the Chicago area-based Catholic Theological Union's (CTU) Romero Scholars Program

- the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) prayer, composed by Bishop Kenneth Untener of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Saginaw, for use in a 1979 homily by Detroit's Cardinal John Dearden for departed priests, but allegedly attributed to (but never spoken by) Archbishop Romero; can be used as a prayer for his cause and/or to him

- the official YouTube channel for his beatification

- a YouTube video called "The Last Journey of Oscar Romero"

- SUPER MARTYRIO, a blog "about the martyrdom" (of Romero)

- Collection of Romero's homilies and meditations

- Remembering Archbishop Oscar Romero (several contemporary and memorial articles)

- Article on Romero, contains picture of Lentz icon

- "Learn from History", 31st Anniversary of the Assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero, The National Security Archive

- Romero A description of the pursuit of justice for Óscar Romero

- El Salvador Marks Archbishop Oscar Romero's Murder by BBC News

- How we killed Archbishop Romero Interviews with Captain Álvaro Rafael Saravia and others

- Witnessing massacre of Romero's funeral Video footage and pictures of the massacre in front of the Cathedral.

- Fundación Monseñor Romero Monsignor Romero Foundation website.

- Westminster Abbey: Óscar Romero

- Archbishop Oscar Romero: A Shepherd's Diary Archbishop Romero's diary in English. It covers the time between March 31, 1978, and March 20, 1980. "Romero's awareness of the historic importance of what was happening in the Church of San Salvador impelled him to maintain this other and more personal record of his pastoral activities."

- Literature by and about Óscar Romero in the German National Library catalogue

- "Óscar Romero" in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- 1917 births

- 1980 deaths

- 1980 in El Salvador

- 20th-century Roman Catholic archbishops

- 20th-century Roman Catholic martyrs

- 20th-century venerated Christians

- Anti-poverty advocates

- Assassinated religious leaders

- Assassinated Salvadoran people

- Beatifications by Pope Francis

- Catholic martyrs of El Salvador

- Deaths by firearm in El Salvador

- Human rights in El Salvador

- Martyred Roman Catholic bishops

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- People from San Miguel Department (El Salvador)

- People murdered in El Salvador

- People of the Salvadoran Civil War

- People with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder

- Roman Catholic activists

- Roman Catholic archbishops of San Salvador

- Salvadoran beatified people

- Salvadoran religious leaders

- Unsolved murders in El Salvador