Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil

| |

|---|---|

Merthyr Tydfil high street | |

Location within Merthyr Tydfil | |

| Population | 43,820 (2011 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SO 0506 |

| Principal area | |

| Preserved county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MERTHYR TYDFIL |

| Postcode district | CF47/CF48 |

| Dialling code | 01685 |

| Police | South Wales |

| Fire | South Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| UK Parliament | |

| Senedd Cymru – Welsh Parliament | |

Merthyr Tydfil (/ˈmɜːrθər ˈtɪdvɪl/;[2] Template:Lang-cy [ˈmɛrθɪr ˈtɪdvɪl]) is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough. The town is administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council and is about 23 miles (37 km) north of Cardiff, Wales. The town is often known as Merthyr.

The town is said to be named after Tydfil, a daughter of King Brychan of Brycheiniog. According to her legend, she was slain at Merthyr by pagans around 480 AD; the place was subsequently named Merthyr Tydfil in her honour.[3] Although merthyr generally means "martyr" in modern Welsh, the meaning here is closer to the Latin martyrium: the mausoleum or church built over the relics of a martyr. Similar examples, all from south Wales, are Merthyr Cynog, Merthyr Dyfan and Merthyr Mawr.

History

Pre-history

Peoples migrating north from Europe had lived in the area for many thousands of years. The archaeological record starts from about 1000 BC with the Celts. From their language, the Welsh language developed.[4] Hillforts were built during the Iron Age and the tribe that inhabited them in the south of Wales was called the Silures, according to Tacitus, the Roman historian of the Roman invaders.

The Roman invasion

The Romans arrived in Roman Wales by about 47–53 AD and established a network of forts, with roads to link them. They had to fight hard to consolidate their conquests, and in 74 AD they built an auxiliary fortress at Penydarren, overlooking the River Taff. It covered an area of about three hectares, and formed part of the network of roads and fortifications; remains were found underneath the football ground where Merthyr Town F.C. play. A road ran north–south through the area, linking the southern coast with Mid Wales and Watling Street via Brecon. Parts of this and other roads, including Sarn Helen, can be traced and walked.

The Silures resisted this invasion fiercely from their mountain strongholds, but the Romans eventually prevailed. In time, relative peace was established and the Penydarren fortress was abandoned by about 120 AD. This had an unfortunate effect upon the local economy, which had come to rely upon supplying the fortress with beef and grain, and imported items such as oysters from the coast. Intermarriage with local women had occurred and many auxiliary veterans had settled locally on farms.

With the Decline of the Roman Empire, Roman legions were withdrawn around 380 AD. By 402 AD, the army in Britain comprised mostly Germanic troops and local recruits, and the cream of the army had been withdrawn across to the continent of Europe. Sometime during this period, Irish Dalriadan (Scots) and Picts attacked and breached Hadrian's Wall. During the 4th and 5th centuries the coasts of Cambria (Wales) had been subject to the raids of Irish pirates, in much the same way as the south and east coasts of Britain had been raided by Saxon pirates from across the North Sea. Around the middle of the 5th century, Irish settlements had been established around Swansea and the Gower Peninsula and in Pembrokeshire and eventually petty kingdoms were established as far inland as Brecon. By about 490 AD hordes of Saxons invaded and settled in the east or "lowland" Britain and the locals were left to their own devices to fight off these new invaders.

The coming of Christianity

The Latin language and some Roman customs and culture became established before the withdrawal of the Roman army. The Christian religion was introduced throughout much of Wales by the Romans, but locally it may have been introduced later by monks from Ireland and France, who made their way into the region following rivers and valleys.

Local legends

Local tradition holds that a girl called Tydfil, daughter of a local chieftain named Brychan, was an early local convert to Christianity, and was pursued and murdered by a band of marauding Picts and Saxons while travelling to Hafod Tanglwys in Aberfan, a local farm that is still occupied. The girl was considered a martyr after her death in around 480 AD. "Merthyr" translates to "Martyr" in English, and tradition holds that, when the town was founded, the name was chosen in her honour. A church was eventually built on the traditional site of her burial.

The Normans

For several hundred years the valley of the River Taff was heavily wooded, with a few scattered farms on the mountain slopes. Norman barons moved in after the Norman Conquest of England, but by 1093 they occupied only the lowlands; the uplands remained in the hands of the local Welsh rulers. There were conflicts between the barons and the families descended from the Welsh princes, and control of the land passed to and fro in the Welsh Marches. During this time Morlais Castle was built two miles north of the town.

Early modern Merthyr

No permanent settlement was formed until well into the Middle Ages. People continued to be self-sufficient, living by farming and later by trading. Merthyr was little more than a village. An ironworks existed in the parish in the Elizabethan period, but it did not survive beyond the early 1640s at the latest. In 1754, it was recorded that the valley was almost entirely populated by shepherds. Farm produce was traded at a number of markets and fairs, notably the Waun Fair above Dowlais.[5]

The Industrial Revolution

Influence and growth of iron industry

Merthyr was close to reserves of iron ore, coal, limestone, lumber and water, making it an ideal site for ironworks. Small-scale iron working and coal mining had been carried out at some places in South Wales since the Tudor period, but in the wake of the Industrial Revolution the demand for iron led to the rapid expansion of Merthyr's iron operations. By the peak of the revolution, the districts of Merthyr housed four of the greatest ironworks in the world: Dowlais Ironworks, Plymouth Ironworks, Cyfarthfa Ironworks and Penydarren.[6] The companies were mainly owned by two dynasties, the Guest and Crawshay families. The families supported the establishment of schools for their workers.

Starting in the late 1740s, land within the Merthyr district was gradually being leased for the smelting of iron to meet the growing demand, with the expansion of smaller furnaces dotted around South Wales.[6] By 1759, with the management of John Guest, the Dowlais Ironworks was founded. This would later become the Dowlais Iron Company and also the first major works in the area. Following the success at Dowlais, Guest took a lease from the Earl of Plymouth which he used to build the Plymouth Ironworks.[6] However, this was less of a success until the arrival in 1763 of a "Cumberland ironmaster, Anthony Bacon, who leased an area of eight miles by five for £100 a year on which he started the Cyfarthfa Ironworks and also bought the Plymouth Works".[6] After the death of Anthony Bacon in 1786, the ownership of the works passed to Bacon's sons, and was divided between Richard Hill, their manager and Richard Crawshay. Hill now owned the Plymouth Iron Works and Crawshay the works at Cyfarthfa. The fourth ironworks was Penydarren, built by Francis Homfray and his son Samuel Homfray in 1784.

It was the need to export goods from Cyfarthfa that led to the construction of the Glamorganshire Canal running from their works right down the valley to Cardiff Bay, stimulating other enterprises along the way.

During the first few decades of the 19th century, the ironworks at Cyfarthfa (and neighbouring Dowlais) continued to expand, and at their height they were the most productive ironworks in the world. 50,000 tons of rails left just one ironworks in 1844, for the railways across Russia to Siberia. With the growing industry in Merthyr, several railway companies established routes linking the works with ports and other parts of Britain. They included the Brecon and Merthyr Railway, Vale of Neath Railway, Taff Vale Railway and Great Western Railway. They often shared routes to allow access to coal mines and ironworks through rugged country, which presented great engineering challenges. According to David Williams, in 1804, the world's first railway steam locomotive, "The Iron Horse", developed by the Cornish engineer Richard Trevithick, pulled 10 tons of iron with passengers on the new Merthyr Tramroad from Penydarren to Quakers Yard.[7] He also claims that this was the "first 'railway' and the work of George Stephenson was merely an improvement upon it".[7] A replica of this locomotive is in the National Waterfront Museum in Swansea. The tramway passed through what is arguably the oldest railway tunnel in the world, part of which can be seen alongside Pentrebach Road at the lower end of the town. The demand for iron was also fuelled by the Royal Navy, which needed cannon for its ships, and later by the railways. In 1802, Admiral Lord Nelson visited Merthyr to witness cannon being made.

Famously, upon visiting Merthyr in 1850, Thomas Carlyle wrote that the town was filled with such "unguided, hard-worked, fierce, and miserable-looking sons of Adam I never saw before. Ah me! It is like a vision of Hell, and will never leave me, that of these poor creatures broiling, all in sweat and dirt, amid their furnaces, pits, and rolling mills."[9]

Living conditions in Merthyr’s slum China

China was the name given to the slum in the Pont-Storehouse region of Merthyr Tydfil. The inhabitants of China were seen as a separate class, away from the respectable areas of Merthyr, and were clearly recognisable by their lifestyle and appearance. In his article, In search of the Celestial Empire, historian Keith Strange compares China to areas of Liverpool, Nottingham and Derby, and states that this area was just as bad if not worse than those "little sodoms".

The worst of housing conditions were to be found in this area, and China was also home to what many regarded as a criminal class. The inhabitants became known as the Chinese and formed a society that became known as the "Empire".

There were at least 1,500 people living in the slum, the inhabitants of which were the poorest of society and had a bad reputation. Their living conditions were some of the most squalid in Britain. The slum was based around narrow streets, badly ventilated and full of crowded houses that led to festering diseases. China became known as "Little Hell"[8] and was notorious for having no toilets but open sewers which caused diseases such as cholera and typhoid. Lice were common, especially amongst workers who worked and slept side by side in the cramped conditions of the slum. These conditions were a concern for the health visitors and housing inspectors who visited its dirty streets. Some of the most memorable and detested dwellings in the slum were the cellars, which were mere one- or two-roomed houses close together, and often with an outrageous number of inhabitants. In the 19th century, people lived in cellars only if they could not afford anything better; or perhaps they preferred being within four cell walls as they had proper shelter and were fed daily.

Poor living conditions and poverty led to the evolution of crime in China. Perhaps fewer children would have committed crimes if the standard of living had been higher. Some of these children were living with their families in these desperate conditions, but there were also numerous homeless, destitute children living on the streets. Many children were turned out of their home and left to fend for themselves at an early age, and many more ran away because of ill treatment.

Many youngsters who had experienced the living conditions in China's slum had grown up in a culture of poverty and often saw criminal offences, such as petty theft, as the only way to get regular meals. These meals were provided in the warmth of a prison cell, conditions many were unfamiliar with. Living conditions were so bad in China's slums that for many young offenders sent to prison, the prospect of regular meals and a roof over their head was an improvement on their normal living conditions.

The Merthyr Rising

After the Industrial Revolution, there was a dramatic decline in young men working in agriculture. Instead they were attracted by the higher wages available in industries such as iron. In 1829, the depression strongly affected Merthyr. Workers' rights did not exist; and sudden dismissal, wage reductions and short-term working had always been imposed by the ironmasters to maximise their profits. The sudden downturn in the market saw the ironmasters quickly dismiss surplus workers and cut the wages of those in work. The working classes were then immediately plunged into hardship, widening the gap in class hierarchy.[9]

The Merthyr Rising of 1831 was precipitated by a combination of the ruthless collection of debts, frequent wage reductions, and the imposition of truck shops. Some workers were paid in specially minted coins or credit notes, known as "truck", which could be exchanged only at shops owned by their employers. Many of the workers objected to both the price and quality of the goods sold in these shops.

Throughout May 1831, the coal miners and others who worked for William Crawshay took to the streets of Merthyr Tydfil, calling for reform, and protesting against the lowering of their wages and general unemployment.

Between 7,000 and 10,000 workers marched, and for four days magistrates and ironmasters were under siege in the Castle Hotel, with the protesters effectively controlling the whole town. Soldiers, called in from Brecon, clashed with the rioters, and several on both sides were killed. Despite the hope that they could negotiate with the owners, the skilled workers lost control of the movement. Several of the supposed leaders of the riots were arrested. One of them, popularly known as Dic Penderyn, was hanged for stabbing a soldier in the leg, becoming known as the first local working-class martyr. It was claimed in 1876 that it was not Lewis who stabbed Black, but another man, Ianto Parker, who fled to America following the incident in order to avoid prosecution.[10] These claims have never been fully verified, although Lewis' innocence is widely accepted throughout Merthyr.

The Chartist movement of 1831 did not consider the reforms put forward by The Reform Act of 1832 to be extensive enough.

The decline of coal and iron

The population of Merthyr reached 51,949 in 1861, but went into decline for several years thereafter. As the 19th century progressed, Merthyr's inland location became increasingly disadvantageous for iron production. Penydarren closed in 1859 and Plymouth in 1880; thereafter some ironworkers migrated to the United States or even Ukraine, where Merthyr engineer John Hughes established an ironworks in 1869, creating the new city of Donetsk in the process.[5]

In the 1870s the advent of coal mining to the south of the town gave renewed impetus to the local economy and population growth. New mining communities developed at Merthyr Vale, Treharris and Bedlinog, and the population of Merthyr rose to a peak of 80,990 in 1911. The growth of the town led to its grant of county borough status in 1908.[5]

A prime example of the decline is the Cyfarthfa Ironworks. The actions, or inactions, of Robert Crawshay ("The Iron King") can be seen as the main reasons for the downfall of Cyfarthfa. The Crawshays refused to modernise by replacing iron production with steel production, using the newly discovered Bessemer process. This led to the closure of the works in 1874, which caused economic hardship and unemployment in Merthyr.

After Robert's death in 1879 his son William Thompson Crawshay took over the Cyfarthfa works. William finally modernised the works, introducing steel production. However it took until 1882 to get the works back up and running. It never fully caught up with the times and with other steel making areas. The ironworks closed once again in 1910. The works briefly made a comeback during the First World War but finally closed for good in 1919. The local steel and coal industries began to decline after the war. By 1932, more than 80% of men in Dowlais were unemployed; 27,000 people emigrated from Merthyr in the 1920s and 1930s, and a Royal Commission recommended that the town's county borough status be abolished. The fortunes of Merthyr revived temporarily during World War II, as war industry was established in the area.

Post-Second World War

Immediately following the Second World War several large companies set up in Merthyr. In October 1948 the American-owned Hoover Company opened a large washing machine factory and depot in the village of Pentrebach, a few miles south of the town. The factory was purpose-built to manufacture the Hoover Electric Washing Machine, and at one point Hoover was the largest employer in the borough. Later the Sinclair C5 was built in the same factory.

Hoover and other companies targeted Merthyr, and its declining coal and iron industries gave space for new businesses to start up there and grow. There were ever-increasing numbers of unemployed workers in the area, and since the Second World War this included women too. "Initially 350 people were employed, by the mid 1970s that number had risen to near 5,000; making Hoover the largest employer in the borough", and therefore strongly filling in for the declining coal and iron industries.

The growing employment of women in Merthyr after the Second World War is extremely significant and can be seen as a result of the introduction of more light manufacturing and consumer-based business – a stark contrast to the heavy industry in the coal and ironworks which had an almost entirely male workforce.

Several other companies built factories, including the aviation components company Teddington Aircraft Controls, which opened in 1946 and closed in the early 1970s. The Merthyr Tydfil Institute for the Blind, founded in 1923, is the oldest active manufacturer in the town.[11]

Cyfarthfa, the former home of the ironmaster William Crawshay II, an opulent mock castle, is now a museum. It houses a number of paintings of the town, a large collection of artefacts from the town's Industrial Revolution period, and a notable collection of Egyptian tomb artefacts, including several sarcophagi.

In 1992, while testing a new angina treatment in Merthyr Tydfil, researchers discovered that the new drug had erection-stimulating side effects for some of the healthy volunteers in the trial study. This discovery formed the basis for Viagra.[12]

In 2006 inventor Howard Stapleton, based in Merthyr Tydfil, developed the technology that gave rise to the recent mosquitotone or Teen Buzz phenomenon.[13]

The Welsh language

In the United Kingdom Census 1891, 68.4% of the population of Merthyr—75,067 inhabitants out of a total of 110,569—spoke Welsh (Edwards, 2001: 131). By the 1911 Census, that figure had fallen to 50.9%, or 37,469 inhabitants out of a total of 74,596 (ibid.). The United Kingdom Census 2011 indicated that 8.9% of the population of Merthyr spoke Welsh.[14]

Industrial legacy

Merthyr has a long and varied industrial heritage, and was one of the seats of the industrial revolution (see history above). Since the end of the Second World War, much of this has declined, with the closure of long-established nearby collieries, and both steel and ironworks. Despite recent improvements, some parts of the town remain economically disadvantaged, and there is a significant proportion of the community who are long-term unemployed.[15][16] In 2006, a Channel 4 series ranked Merthyr Tydfil as the United Kingdom's third-worst place to live.[17] In the 2007 edition of the same series, Merthyr had improved to fifth-worst.[18]

Open cast mining

In 2006, a large open cast coal mine, which will extract 10 million tonnes of coal over 15 years, was authorised just east of Merthyr as part of the Ffos-y-fran open cast mine.

Government

The Municipal Borough of Merthyr Tydfil was created in 1905, with eight electoral wards, with the council taking over the roles of Merthyr Tydfil Urban District Council. Merthry Tydfil was granted county status in 1908, which it retained until 1974.[19] Governed by Mid Glamorgan County Council from 1974 to 1996, Merthyr Tydfil also elected representatives to Merthyr Tydfil District Council (with Vaynor joining the District).[19][20]

Since 1996 Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council has been the governing body for the town and the County Borough, which stretches as far south as Treharris and Bedlinog. The town includes the electoral wards of Park, Penydarren, Cyfarthfa, Gurnos, Dowlais, Vaynor, and Town.[21]

The Member of Parliament for the Merthyr Tydfil and Rhymney constituency is Gerald Jones, and the Senedd member is Dawn Bowden MS.

Religion

Anglican churches

Merthyr was regarded as a nonconformist stronghold in the 19th century, but the chapels declined rapidly from the 1920s onwards and most are now closed.

The Church did, however, seek to counterbalance the influence of nonconformity in the 19th century, and Merthyr had a succession of notable clergymen as parish priests. Among them was John Griffith, rector of Merthyr from 1858 until his death in 1885. Griffith had previously been the incumbent at Aberdare where he had created controversy for his evidence to the commissioners preparing the 1847 Education Reports. His views became more tempered over time however.[22] Griffith's move to Merthyr Tydfil saw him take over a much larger and more established parish than Aberdare. He became less than popular with the church authorities, however, as a result of his support for disestablishment. In July 1883 he stated "I have been for years convinced that nothing but Disestablishment, the separation of the Church from the State, can ever reform the Church in Wales."[23]

Griffith's funeral was said to have been attended by between 12,000 and 15,000 people.[24] "I venture to declare," wrote one correspondent, "no man in this part of the kingdom could be more popular in his day and generation than the Rev. John Griffith." Among the nonconformist ministers present at the funeral was his old rival, Dr Thomas Price of Aberdare.[25]

Another influential character is Sir John Guest, who contributed greatly to the building of St. John's Church, which was named after its founder and benefactor. Despite the generally small congregations of Anglican churches, St John's thrived: it held two services each Sunday, two services in English and also two in Welsh. This church was significant in the plan to counterbalance nonconformity in Merthyr. However, there are now plans for its conversion to residential flats which will retain its original structure.[citation needed]

Nonconformity

Merthyr was notable in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for a large number of nonconformist places of worship, most of which held services in the Welsh language. One of the earliest chapels was Ynysgau, which dated back to 1749. The chapel was unfortunately demolished in 1967 as part of the Merthyr Town Improvement Scheme.[26] The original cause at Ynysgau was established by various ‘dissenters’ from the Church of England[27] and it was acquired by the Independents (Congregationalists) by the early nineteenth century.[28] Other early chapels were Zion and Ebenezer (Baptists), Zoar and Bethesda (Independents) and Pontmorlais (Calvinistic Methodists).

The Merthyr Hebrew Congregation

Merthyr Tydfil had the largest Jewish community in Wales in the 19th century: at its height there were around 400 Jewish people living in the town.[29] As the Jewish population had increased, the Merthyr Hebrew Congregation was founded in 1848 and a cemetery consecrated a few years later at Cefn-Coed.[29] The Merthyr synagogue was built in 1875. The Jewish community has now gone from the town. Religious services stopped when it had a male Jewish population of under 10 men, the minyan (quorum) for religious services.[29] In the 1980s the 120-year-old synagogue was put up for sale and it became a Christian Centre and then a gym. In 2009 permission was granted for the former synagogue to be turned into flats.[30]

Culture

The town has held many cultural events. Local poets and writers hold poetry evenings in the town, and music festivals are organised at Cyfarthfa Castle and Park. With this in mind, Menter Iaith Merthyr Tudful (the Merthyr Tydfil Welsh Language Initiative) has successfully transformed the Zoar Chapel and the adjacent vestry building in Pontmorlais into a community arts venue, Canolfan Soar and Theatr Soar, which run a whole programme of performance events and activities in both Welsh and English, together with a cafe and book shop, specialising in local interest and Welsh language books and CDs.[31] Also on Pontmorlais, Merthyr Tydfil Housing Association was successful in a number of funding bids to develop the Old Town Hall into a new cultural centre, working in partnership with Canolfan a Theatr Soar to turn the Pontmorlais area into a cultural quarter. The Old Town Hall facility was launched on Saint David's Day 2014 as an arts centre. With references to the 1831 Merthyr Rising and the building's red bricks, the venue has been named Redhouse Cymru.[32] Merthyr Tydfil College's Arts and Media departments occupy part of the building, holding occasional professional performances at Redhouse's Dowlais Theatre and providing opportunities for students to perform dance, musicals, plays, and instrumental and vocal concerts.

Merthyr Tydfil has several choirs. Dowlais Male Voice Choir, Ynysowen Male Voice Choir, Treharris Male Voice Choir, Merthyr Tydfil Ladies Choir, Con Voce, Cantorion Cyfarthfa, St David's Church Choir, St David's Choral Scholars, Merthyr Aloud and Tenovus. These choirs perform locally, around the world and in the media.

Merthyr has several historical and heritage groups:

The Merthyr Tydfil Heritage Regeneration Trust, which has as its aim – "To preserve for the benefit of the residents of Merthyr Tydfil and of the Nation at large whatever of the Historical, Architectural and Constructional Heritage may exist in and around Merthyr Tydfil in the form of buildings and artefacts of particular beauty or of Historical, Architectural or Constructional interest and also to improve, conserve and protect the environment thereto."[33]

The Merthyr Tydfil Historical Society, which has as its aim – "To advance the education of the public by promoting the study of the local history and architecture of Merthyr Tydfil".[34]

The Merthyr Tydfil Museum and Heritage Groups, which has as its aim – "To advance the education of the public by the promotion, support and improvement of the Heritage of Merthyr Tydfil and its Museums."[35]

Merthyr's Central Library, which is in a prominent position in the centre of the town, is a Carnegie library.

Merthyr hosted the National Eisteddfod in 1881 and 1901 and the national Urdd Gobaith Cymru Eisteddfod in 1987.

Merthyr, like nearby Aberdare, is known for its thriving music scene. The town has produced several bands that have achieved national success, including The Blackout and Midasuno. From 2011–14 the town held the Merthyr Rock Festival at Cyfarthfa Park.[36] To complement this, the town now holds the Merthyr Rising each year - a three day celebration of the town's history through local music which is held on the site of the Rising itself in Penderyn Square at the junction of Castle Street and High street.

Tourism

The town is in a South Wales Valleys environment just south of the Brecon Beacons National Park.

Transport

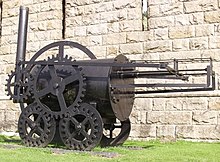

The "Pen-y-Darren" locomotive

In 1802, Homfray, the Master of the Penydarren Ironworks, commissioned engineer Richard Trevithick to build one of his high-pressure steam engines to drive a hammer at the Penydarren Ironworks. With the assistance of works engineer Rees Jones, Trevithick mounted the engine on wheels and turned it into a locomotive. In 1803, Trevithick sold the patents for his locomotives to Homfray.

Homfray was so impressed with Trevithick's locomotive that he made another bet with Crawshay, this time for 500 guineas, that Trevithick's steam locomotive could haul 10 tons of iron along the Merthyr Tydfil Tramroad from Penydarren (51°45′03″N 3°22′33″W / 51.75083°N 3.37583°W) to Abercynon (51°38′44″N 3°19′27″W / 51.64556°N 3.32417°W), a distance of 9.75 miles (15.69 km). Amid great interest from the public, on 21 February 1804 it successfully carried 11.24 tons of coal, five wagons and 70 men over the full distance, in 4 hours and 5 minutes, at an average speed of 2.4 mph (3.9 km/h). As well as Homfray, Crawshay, and the passengers, other witnesses included Mr. Giddy, a respected patron of Trevithick, and an 'engineer from the Government'. The latter was probably a safety inspector, who would have been particularly interested in the boiler's ability to withstand high steam pressures. This opened the way for others to develop Trevithick's ideas and the railway as we know it today can rightly claim to have been born in Merthyr Tydfil.

In modern Merthyr, behind the monument to Trevithick's locomotive, is a stone wall, which is the sole remainder of the former boundary wall of Penydarren House. There is a full-scale working replica of Trevithick's 1804 steam-powered railway locomotive in the National Waterfront Museum, Swansea.

Roads

Road improvements mean the town is increasingly a commuter location and has shown some of the highest house price growth in the UK.[37][38]

Public transport

Regular trains services operate from Merthyr Tydfil railway station to Cardiff Queen Street and Cardiff Central. Merthyr Tydfil bus station is located on Castle Street to the north of the town centre. In 2019 building started on a new bus station on the site of the former police station in Swan Street, which was scheduled to open in 2020. The new bus station will be located closer to the railway station to facilitate passenger interchange as part of the proposed South Wales Metro network.[39]

Employment

Merthyr relies on a combination of public sector and manufacturing and service sector companies to provide employment. The Welsh Government has recently opened a major office in the town[40] near a large telecommunications call centre (T-Mobile & EE.) Hoover (now part of the Candy Group) has its Registered Office in the town and remained a major employer until it transferred production abroad in March 2009, with the loss of 337 jobs after the closure of its factory[41]

Sports and leisure

Boxing

Merthyr is particularly known for its boxers, both amateur and professional. Famous professional pugilists from the town include Johnny Owen, Howard Winstone, and Eddie Thomas with a series of bronze sculptures in the town commemorating their achievements.

Where the sculpture of Eddie Thomas stands was also the site of The Bethesda Community Arts Centre in the 1980s.

Football

Merthyr has a football team, Merthyr Town. 'The Martyrs' currently compete in England's Evostick Southern Football League and play their home games at Penydarren Park.

The town was home to the professional Football League club Merthyr Town F.C., which folded in the 1930s; Merthyr Tydfil AFC was founded in 1945. In 1987 they won the Welsh Cup and qualified for the European Cup Winners' Cup. In the first round, they won 2–1 against Italian football team Atalanta in the first leg at Penydarren Park. However, they lost the return leg, 3–2 on aggregate.

2008 marked the centennial of football at Penydarren Park. After going into liquidation in 2010, the club dropped down three divisions, reverted to the name of Merthyr Town and made Rhiw Dda’r their new home ground. Following promotion[42] the club moved back to Penydarren Park in July 2011.[43]

Rugby

- Union

The local rugby union club, Merthyr RFC, is known as 'the Ironmen'. It was one of the 12 founding clubs of the Welsh Rugby Union in 1881. The club competes in the Principality Premiership and play home games at The Wern.

- League

From 2017, semi-professional League 1 club South Wales Ironmen, previously known as South Wales Scorpions, will play in the town at Merthyr RFC's ground, The Wern. Merthyr is also home to the Tydfil Wildcats Rugby League team, which played at The Cage in Troedyrhiw until September 2010. Merthyr Tydfil was one of the first rugby league sides in Wales in 1907 and beat the first touring Australian side in 1908.

Mountain biking

Bikepark Wales, the UK's first purpose-built mountain biking centre, is located at Gethin Woods, Merthyr Tydfil.[44]

Outdoor pursuits

Parkwood Outdoors Dolygaer is an outdoor activity centre that was opened in 2015 on the site of a earlier centre operated by the local education authority. Activities include canoeing and stand-up Paddleboarding on the Pontsticill Reservoir.[45]

Education

Notable people

Among those born in Merthyr are:

- Gareth Abraham – professional footballer[46]

- Laura Ashley – fashion designer and retailer[47]

- Des Barry – author

- Members of The Blackout - Rock band featuring Sean Smith

- Mario Basini – journalist, broadcaster and author

- William Berry, 1st Viscount Camrose – newspaper proprietor, and his brothers Seymour Berry, 1st Baron Buckland and Gomer Berry, 1st Viscount Kemsley

- Jamie Bevan – Welsh language activist[48]

- Nathan Craze – professional ice hockey goaltender[49]

- Gordon Davies - Fulham F.C. leading goal scorer and Wales international football player

- Martyn Davies – weather presenter, meteorologist and former child actor

- Richard Davies – actor

- Timothy Evans – wrongly convicted and hanged for murder

- Kevin Gall – professional footballer

- Sir Samuel Griffith – Australian politician and Premier of Queensland

- Richard Harrington – actor

- John Hughes – businessman

- Ciaran Jenkins – broadcaster and journalist

- Declan John – professional footballer

- David W. Jones (1815–1879), Wisconsin politician

- Glyn Jones – poet

- John Edward Jones – American politician and the eighth Governor of Nevada[50]

- William Ifor Jones – American conductor and organist

- Brian Law – Welsh international football player

- Chelsea Lewis - Welsh international netball player

- Peter Locke - Welsh professional darts player

- Julien Macdonald – fashion designer

- Man – prog-rock band

- Leslie Norris – poet

- Geoffrey Olsen – artist

- Johnny Owen – boxer

- Jonny Owen – actor, broadcaster and producer

- Morgan Owen - poet and author

- Joseph Parry – composer

- Gustavius Payne – artist

- Mark Pembridge – Wales international football player

- Robert Sidoli – Welsh rugby international

- Eddie Thomas – boxer

- Penry Williams – artist

- Howard Winstone – boxer

Other notable residents have included poet and author Mike Jenkins (his son Ciaran mentioned above) and daughter Plaid Cymru politician Bethan Jenkins; poet, journalist, and Welsh Nationalist Harri Webb; General Secretary of the PCS trade union Mark Serwotka; poet, author, and Welsh language activist Meic Stephens; and poet, author, and journalist Grahame Davies. Sam Hughes began his career as a noted player of the ophicleide in the Cyfarthfa Brass Band. One of the first two Labour MPs to be elected to parliament was the Scot Keir Hardie, for Merthyr Tydfil constituency.

Notable descendants of Merthyr include the singer-songwriter Katell Keineg, whose mother is a native of Merthyr; the "Chariots of Fire" athlete Harold Abrahams' mother Esther Isaacs; and the grandfather of Rolf Harris. The 1970s juvenile group The Osmonds have traced their ancestry to Merthyr.[51]

Lady Charlotte Guest, publisher and translator, married ironmaster John Josiah Guest in 1833 and moved to his mansion in Dowlais where she lived for many years and it was there she translated the stories of the Mabinogion in 1838–45 and 1877.[52]

References in art and literature

- Horatio Clare's retelling of one of the Mabinogion tales, The Prince's Pen (Seren) refers to Merthyr as being "declared an insurgent zone", and that people would refer to "'what happened at Merthyr' for years to follow".[53]

- In the third episode of the 1978 BBC sitcom Going Straight, Merthyr is referred to as having ".. more pubs.. than anywhere else in Britain, and they're all shut Sundays."

- In Jasper Fforde's Thursday Next series (set in an alternate history), Merthyr is the capital of an independent People's Republic of Wales.

- Australian poet Les Murray references his experiences in the town in his poem, "Vindaloo in Merthyr Tydfil".

- Canadian songwriter Jane Siberry once visited Merthyr Tydfil, and used the line "and my heart is black and heavy, it is slags of Merthyr Tydfil" as an image to convey feelings of abandonment and sadness in her song "You Don't Need", from the 1984 album, No Borders Here.

Twinnings

- Clichy, Hauts-de-Seine, France, since 1980[54][55]

See also

References

- ^ UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Merthyr Tydfil Built-up area (W37000363)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ Wells, John (12 January 2010). "Merthyr". John Wells's phonetic blog. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ^ Farmer, David Hugh. (1978). "Tydfil". In The Oxford Dictionary of Saints.

- ^ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 1757.

- ^ a b c The Welsh Academy Encyclopedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press 2008.

- ^ a b c d Williams, David (1963). A Short History of Modern Wales (3rd ed.). London: John Murray. p. 80.

- ^ a b Williams, David (1963). A Short History of Modern Wales (3rd ed.). London: John Murray. p. 83.

- ^ "The Story of Wales: Life in Merthyr Tydfil's 19th Century 'Little Hell'". BBC News. 12 March 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ "History of the Force: The Merthyr Rising". South Wales Police Force. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Lewis, Richard ('Dic Penderyn'; 1807/8 – 1831)". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- ^ MTIB.co.uk

- ^ Staff (4 September 2007). "Blue wonder: Happy birthday Viagra". independent.co.uk. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Firm's ringtone 'next Crazy Frog'". BBC News. 14 June 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ "Cyfrifiad 2011: canlyniadau a newidiadau er 2001" (in Welsh). Welsh Language Commissioner. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ "WalesOnline: News, sport, weather and events from across Wales". icwales.icnetwork.co.uk.

- ^ "Ten reasons to love 'worst town'". BBC News. 10 August 2005. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ "Programmes – All – Channel 4". Channel 4. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Programmes – All – Channel 4". Channel 4. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Merthyr Tydfil Borough Records - Administrative / Biographical History". Archives Hub (Jisc). Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Merthyr Tydfil Welsh District Council Election Results 1973-1993" (PDF). The Elections Centre (Plymouth University). Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Election Maps". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ Wills. "John Griffith". Welsh Journal: 76.

- ^ "Welsh Biography Online". Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ "Death of the Rector of Merthyr". Aberdare Times. 2 May 1885. Archived from the original on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ Ap Gwilym (2 May 1885). "The Funeral". Weekly Mail. Archived from the original on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ "Merthyr Tydfil". Genuki. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ Rees, Thomas; Thomas, John (1871). Hanes Eglwysi Annibynnol Cymru, Vol. 2. p. 244. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ Brewer, Steve (18 November 2016). "The Birth of Non-Conformity in Merthyr". The Melting Pot. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ a b c George, Alan. "The Synagogue". Old Merthyr Tydfil. Alan George. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ "Merthyr synagogue in Thomastown set to be turned into flats". Wales Online. 18 November 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ fkcreate. "Merthyr Tudful". Theatr Soar. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ "Redhouse". Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Merthyr Tydfil Heritage Trust". Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Merthyr Tydfil Historical Society". Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Merthyr Tydfil Museum and Heritage Group". Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Index of /".

- ^ "Merthyr named UK's house hotspot". BBC News. 16 October 2004. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ "House price boom as market grows". BBC News. 8 August 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ Lewis, Anthony (31 July 2019). "Work starts on building Merthyr Tydfil's new bus station imminently". Wales Online. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "Assembly building in valleys town". BBC News. 30 November 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ "End of the line for Hoover plant". 13 March 2009 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Merthyr Town celebrate Western League promotion". BBC Sport. 4 April 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Match Report: Merthyr Town 1 – 9 Llanelli[permanent dead link]

- ^ http://www.bikeparkwales.com/about-us. Bikepark Wales, "About Us". Retrieved 21/07/14

- ^ "Courses at Dolygaer". Parkwood Outdoors Dolygaer. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "Gareth Abraham". Post War English & Scottish Football League A – Z Player's Database. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ "South East Wales Arts – Laura Ashley". BBC. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ "Gareth Jamie Bevan, Man Who Trashed Conservative MP's Office Over S4C, Jailed". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ "Nathan Craze". hockeyDB.com. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ "John Edward Jones". Find A Grave. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ "South East Wales - BBC News". BBC News.

- ^ "Lady Charlotte Guest". Data Wales. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Horatio Clare (18 October 2011). "The Prince's Pen". Seren Books. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ ""Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)." Retrieved on 12 January 2012. - ^ "http://www.francemag.com/france-travel-travel-guide-and-information-twin-towns--211." Retrieved on 12 January 2012.

The population given as 38,000 is for the parishes around the town centre: the population of the County Borough at the 2011 census was 58,800 and in 2014 the population was 59,500.

Bibliography

- A Brief History of Merthyr Tydfil by Joseph Gross. The Starling Press. 1986

- The Merthyr Rising by Gwyn A Williams. University of Wales Press,

- The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press,

- People, Protest and Politics, case studies in C19 Wales By David Egan, Gomer 1987

- Cyfres y Cymoedd: Merthyr a Thaf, edited by Hywel Teifi Edwards. Gomer, 2001

- Civilizing the Urban: Popular culture and Urban Space in Merthyr, c. 1870–1914 by Andy Croll. University of Wales Press. 2000. ISBN 978-0708316375

- Methyr Tydfil A.F.C. 1945–1954: The Glory Years By Philip Sweet. T.T.C. Books. 2008

- The Eccles, Antiquities of the Cymry; or The Ancient British Church by John Williams (1844), p116.

- Noteworthy Merthyr Tydfil Citizens by Keith L. Lewis-Jones. Merthyr Tydfil Heritage Trust 2008.mtht.co.uk

- Keith Strange, In Search Of The Celestial Empire, Llafur, Vol 3; no.1 (1980)

- Merthyr Historian volumes 1 – 21, Merthyr Tydfil Historical Society. mths.co.uk

- Wills, Wilton D. (1969). "The Rev. John Griffith and the revival of the established church in nineteenth century Glamorgan". Morgannwg. 13: 75–102. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

External links

- Old Merthyr Tydfil — Historical Photographs of Merthyr Tydfil.

- Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council

- "Merthyr Tydfil Life". BBC. Archived from the original on 3 October 2008.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 3 March 2008 suggested (help) - www.geograph.co.uk : photos of Merthyr Tydfil and surrounding area