Transport in Berlin

Berlin has developed a highly complex transportation infrastructure providing very diverse modes of urban mobility.[1] 979 bridges cross 197 kilometers of innercity waterways, 5,334 kilometres (3,314 mi) of roads run through Berlin, of which 73 kilometres (45 mi) are motorways.[2] Long-distance rail lines connect Berlin with all of the major cities of Germany and with many cities in neighboring European countries. Regional rail lines provide access to the surrounding regions of Brandenburg and to the Baltic Sea.

Road transport

In 2013, 1.344 million motor vehicles were registered in the city.[3] With 377 cars per 1000 residents in 2013 (570/1000 in Germany), Berlin as a Western world city has one of the lowest numbers of cars per capita. Congestion pricing has been proposed.

Autobahn

Berlin is linked to the rest of Germany and neighbouring countries by the country's autobahn network, including the:

- A2 to Hannover and the Ruhr area, with links to Frankfurt am Main and western Germany

- A9 to Leipzig, Nuremberg and Munich, with links to Frankfurt am Main and southern Germany

- A11 to Szczecin, with links to north-east Germany and Poland

- A12 to Frankfurt (Oder), with links to Poland

- A13 to Dresden, with links to Poland and the Czech Republic

- A24 to Hamburg, with links to Rostock and north-west Germany

All of these autobahn terminate at the A10 Berliner Ring, a 196-kilometre-long (122 mi) autobahn that encircles the city at some distance from the centre, and largely in the surrounding state of Brandenburg. Central Berlin is connected to the A10 by several shorter autobahns:

- A111 to the northwest (towards the A24 and Tegel Airport)

- A113 to the southeast (towards the A12, A13 and Schönefeld Airport)

- A114 to the north (towards the A11)

- A115 to the southwest (towards the A2 and A9)

The A111, A113 and A115 connect with the A100 Berliner Stadtring, an autobahn that forms a half circle to the west of the inner city, and is one of the busiest motorways in Germany.[4] There are plans to extend this motorway to form a full circle around the inner city.

Bus

The Central Bus Station Berlin (Zentraler Omnibusbahnhof Berlin, or ZOB) is located in Berlin's western district Charlottenburg, close to the Messe Berlin exhibition grounds under the Funkturm. The bus station served as an alternative to the rail transit corridors during German partition. From ZOB intercity buses run to destinations throughout Germany and Europe. Some intercity buses also stop at various other points in Berlin, including the airports and major railway stations.

Taxicabs

In Berlin and Germany, taxicabs are mostly light yellow/beige ivory-coloured. The RAL number is 1015. Since 2005 the colour has not been compulsory anymore. Taxis have a small illuminated cylinder-like "TAXI" sign on the roof of the car (on when available, off otherwise).

Typically the taxicabs are Mercedes-Benz E-Class and S-Class along with other, mainly German, brands. Taxicabs are either sedans, station wagons, or MPVs. Common station wagon taxicabs include Mercedes-Benz C-Class. Among the MPVs, Mercedes-Benz B-Class, and Mercedes-Benz Vianos are common. Most taxicabs are automatic transmission, and some have navigation systems on board. Rates are usually near to other western European countries.[5]

In Berlin taxis have a special low fare (€4) called "Kurzstrecke" for distances less than 2 kilometers. "Street Hail" is a common practice in Berlin because cabs circle the cities when vacant. Other hailing methods such as telephone based calls or taxi apps are common as well.

Cycling

Berlin is known for its highly developed bike lane system. Among cities with more than one million inhabitants Berlin is a metropolis with one of the highest rates of bicycle commuting in the world. Around 1,500,000 daily rides account for 13% of total traffic in 2010. The Senate of Berlin aims to increase the number to 18% of city traffic by the year 2025.

Riders have access to 620 kilometres (390 mi) of bike paths including some 150 kilometres (93 mi) of mandatory bicycle paths, 190 kilometres (120 mi) of off-road bicycle routes, 60 kilometres (37 mi) of bike lanes on the roads, 70 kilometres (43 mi) of shared bus lanes which are also open to bicyclists, 100 kilometres (60 mi) of combined pedestrian/bike paths and 50 kilometres (31 mi) of marked bike lanes on sidewalks.[6][7]

The Berlin-Copenhagen Cycle Route (Radfernweg Berlin-Kopenhagen) is a 630 km (390 mi) long-distance cycling route that connects the German and Danish capital cities. The German portion of the route, between Berlin and Rostock, is approximately 370 km (230 mi); the Danish portion, between Gedser and Copenhagen, is approximately 260 km (160 mi). From Rostock to Gedser, cyclists must take a ferry.

Modal share

The modal share development within the city of Berlin in percentage:

| Modes of transport | 2008 | 2013 [8] | 2018 [9] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Walking | 32 | 31 | 30 |

| Motorized transport | 33 | 30 | 26 |

| Public transport | 24 | 27 | 27 |

| Cycling | 11 | 13 | 18 |

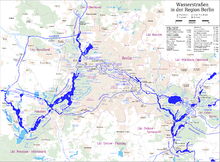

Water transport

Berlin is linked to the Baltic Sea, the North Sea, and the River Rhine by an extensive network of rivers, lakes and canals. An equally extensive network of waterways exists within the city boundaries, providing local access and various short-cuts. The waterways accommodate a mixture of commercial traffic, sightseeing tour boats, ferries and a large fleet of private leisure boats.

Waterways

Berlin city centre is located on the River Spree, which runs roughly east to west across the city. The River Dahme joins the Spree at Köpenick, in the city's eastern suburbs. At Spandau the Spree joins the River Havel, which flows roughly north to south along the city's western boundary. To both east and west of the centre of Berlin, all three of these rivers flow through substantial chains of lakes. These include the Tegeler See and Großer Wannsee to the west, and the Müggelsee, Langer See, Seddinsee and Zeuthener See to the east.[10]

The Elbe–Havel Canal links the River Havel downstream of Spandau with both the River Elbe, which flows into the North Sea at Hamburg, and with the Mittelland Canal, which stretches across Germany to a network of canals that provide a link to the River Rhine. Both the Oder–Havel and Oder–Spree canals provide routes from the Berlin area to the River Oder, which flows into the Baltic Sea near Szczecin and provides links to Poland. The Oder-Havel Canal links with the River Havel north of Spandau, whilst the Oder-Spree Canal links with the River Dahme east of Köpenick.[10]

The most important canals within Berlin run roughly east to west between the rivers Spree and Havel. The canal system to the north of the Spree begins with the Berlin-Spandau Ship Canal, which runs from the Spree near the Hauptbahnhof to the River Havel above Spandau. The Westhafen Canal and the Charlottenburg Canal, both near Charlottenburg, provide further connections between the Berlin-Spandau Ship Canal and the River Spree.[10]

The main canal to the south of the Spree is the Teltow Canal, which runs from the Dahme south of Köpenick through the southern part of Berlin to an arm of the Havel just east of Potsdam. A shorter canal, the Landwehr Canal, parallels the Spree through the centre of Berlin. It begins at the Spree between Treptow and Kreuzberg and rejoins the Spree in Charlottenburg. The Neukölln Ship Canal connects the Landwehr Canal with the Teltow Canal; while the Britz Canal connects the Teltow Canal with the Spree at Baumschulenweg.[10]

Whilst not within Berlin, the existence of the city and its partition led to the construction of the Havel Canal in 1951–2. This canal provides an alternative route between Hennigsdorf and Paretz, both then in East Germany, and avoids the stretch of the River Havel that was under the political control of West Berlin.[10]

Ports

Berlin's largest port is the Westhafen ("west port"), in Moabit (Mitte), with an area of 173,000 m2 (1,860,000 sq ft). It lies at the intersection of the Berlin-Spandau Ship Canal and the Westhafen Canal. It handles the shipping of grain and pieced and heavy goods. The Südhafen ("south port"), which actually lies along the Havel in Spandau, in far western Berlin, covers an area of about 103,000 m2 (1,110,000 sq ft) and also handles the shipping of pieced and heavy goods. The Osthafen ("east port"), with an area of 57,500 m2 (619,000 sq ft), lies along the Spree in Friedrichshain. The Hafen Neukölln, at only 19,000 m2 (200,000 sq ft), is located along the Neuköllner Ship Canal in Neukölln. It handles the shipping of building materials.

Sightseeing boats operate on the central section of the River Spree and its adjoining waterways on a frequent basis. Common tours operated include short tours on the River Spree in the city centre, and a three-hour circuit of the city centre via the River Spree and the Landwehr Canal. Other sightseeing boats operate on the various lakes to the east and west of Berlin.[10][11]

Several ferry services operate on and across Berlin's waterways (see ferries below).

Railways

Long-distance rail lines connect Berlin with all of the major cities of Germany and with many cities in neighboring European countries. Regional rail lines of the Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg provide access to the surrounding regions of Brandenburg and to the Baltic Sea. The Berlin Hauptbahnhof is the largest grade-separated railway station in Europe.[12]

Deutsche Bahn runs high speed ICE trains to domestic destinations like Hamburg, Munich, Cologne, Stuttgart, Frankfurt am Main and others. It also runs a BER airport express rail service, as well as trains to several international destinations (some of them in cooperation with railroads in other countries) like Vienna, Prague, Zürich, Warsaw, Budapest and Amsterdam.

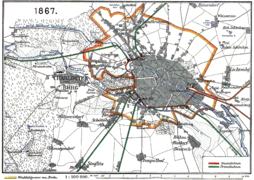

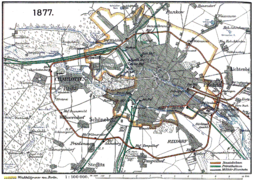

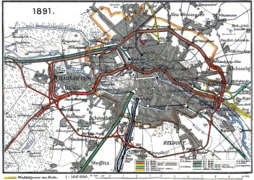

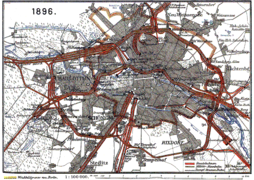

- Berlin Railways from 1846 to 1896 and their successive nationalization

-

1846

-

1867

-

1877

-

1882

-

1891

-

1896

Regional trains

Berlin is the centre of a system of regional trains operated by Deutsche Bahn, which operate to destinations within the Berlin-Brandenburg suburban area beyond the range of the S-Bahn. There are two kinds of regional trains, the frequently stopping Regionalbahn (RB), and the faster Regional-Express (RE).

Unlike the S-Bahn, the network of regional trains does not have its own segregated tracks, but rather shares tracks with longer distance passenger and freight services. Within Berlin, regional services stop less frequently than S-Bahn services, especially where they run parallel to U-Bahn or S-Bahn lines.

Regional trains often continue outside the Berlin-Brandenburg suburban area, but within that suburban area they use the common public transport tariff managed by the Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg (VBB). This covers the city of Berlin and approximately 20 kilometres (12 mi) beyond the city boundaries. These tickets are not valid on DB InterCity trains, Intercity-Express trains and international trains, even within Berlin.

Public transport

Berlin's local public transport network is under the regional transit authority named Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg (VBB), a common undertaking of the two federal states (Bundesland) Berlin and Brandenburg, plus the counties (Landkreis) and cities of the Land of Brandenburg. The VBB is the planning authority for regional transport, awards service contracts to private and public companies, and sets the tariffs. For transport lines and networks which do not pass a county's borders, the locality is responsible. This also means that the city-state of Berlin is the sole authority to award service contracts for networks and lines which do not pass beyond the city limits, but has to come to an agreement with the surrounding Land Brandenburg for regional rail and bus transport, i.e. the S-Bahn and regional trains.

The city's transit networks consists of several separate networks, with heavy and light rail transport with five different and incompatible electrification systems. These include the U-Bahn and S-Bahn urban rail systems, regional railway services, a tramway system, a bus network and a number of ferry services. There are a large number of common interchange stations between the different modes.

All these services are, as explained above, under the common public transport tariff run by the Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg (VBB). This covers the city of Berlin and approximately 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) beyond the city boundaries. The area is split into three zones. Zone A is the central parts of the city (inside the Ringbahn), and zone B is the outer parts of Berlin City. Zone C covers an area beyond the city boundaries.[13][14]

Ticket fares have a slight price difference between these three zones. For instance, in June 2012, a one-day ticket for zone A+B was priced at €6.30, a zone B+C one-day travel ticket was €6.60, and for all three zones A+B+C, the price was €6.80.[13][14]

| System | Stations / Lines / Net length | Passengers per year | Operator / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-Bahn | 166 / 15 / 327 km (203 mi) | 417,000,000 (2015) | DB / Mainly overground rapid transit rail system with suburban stops |

| U-Bahn | 173 / 10 / 146 km (91 mi) | 507,000,000 (2012) | BVG / Mainly underground rail system / 24h-service on weekends |

| Tram | 404 / 22 / 189 km (117 mi) | 181,000,000 (2014) | BVG / Operates predominantly in eastern boroughs |

| Bus | 3227 / 151 / 1,626 km (1,010 mi) | 405,000,000 (2014) | BVG / Extensive services in all boroughs / 62 Night Lines |

| Ferry | 5 lines | BVG / All modes of transport can be accessed with a single ticket |

U-Bahn

The U-Bahn is an urban rapid transit rail system, and is entirely within the city borders. Whilst the majority of the system is underground, some sections operate on elevated tracks or at street level. It is operated by the Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG), the city owned municipal transport operator, and uses the common public transport tariff managed by the Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg (VBB). In terms of system length the Berlin U-Bahn is the largest mainly underground metro system in Germany and the fifth largest in Europe.

The U-Bahn now comprises nine lines with 173 stations and a total length of 147 kilometres (91+1⁄2 mi). Trains run every two to five minutes during peak hours, every five minutes for the rest of the day and every ten minutes in the evening and on Sunday. They travel 132 million km (83 million mi), carrying 400 million passengers, over the year.[15][16]

The first line of the U-Bahn opened in 1902, and construction has continued spasmodically since then, with the most recent extension (U5 to Berlin Hauptbahnhof) opening in 2020. The first four lines to be built were built with a narrower loading gauge and a slightly different electrification method to the later lines. This is most noticeably seen in the narrower trains on the earlier lines, and rolling stock cannot easily be interchanged between the two groups of lines. However, trains designed for the lines U1-U4 have been used during rolling stock shortages on the other lines with so called "Blumenbretter" (flower boards) filling in the gap.

During the division of the city, the U-Bahn system was itself partitioned. One line – the U5 – was entirely within East Berlin, and another – the U2 – was operated in two sections, one by each of the two sides. The remaining lines were nominally within West Berlin, although two of them passed under East Berlin without stopping, except at the Friedrichstraße station, which served as a transfer point and border crossing. The U-Bahn stations physically located in East Berlin which West Berlin services passed through without stopping came to be known as ghost stations.

Whilst the city remained partitioned, there was major expansion of the U-Bahn in the west, driven both by the availability of funds from commercially successful West Germany and by the desire to provide alternatives to the East German run S-Bahn. East German authorities extended the sole line then entirely in East Berlin (today's U5) in stages from its then terminus at Friedrichsfelde all the way to the city boundary at Hönow Since reunification, expansion has been less fast, in part due to fewer funds being available and in part due to ongoing tram expansion.

S-Bahn

The S-Bahn has aspects of both rapid transit and commuter rail operation. Historically it developed from commuter services provided by main line railway operators, but now runs on tracks that are separate from, but often parallel to, other trains. Most of the system is operated at ground level, but there are significant sections of elevated tracks and tunnels. It has a somewhat longer average distance between stations than the U-Bahn, and it also serves some of the closer suburbs in Brandenburg. It is operated by a subsidiary of Deutsche Bahn, the national rail operator, and uses the common public transport tariff managed by the Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg (VBB).[17] In terms of system length the Berlin S-Bahn is among the Top10 largest metro systems in the world.

The S-Bahn now comprises 15 routes with 166 stations and a total length of 331 kilometres (205+1⁄2 mi). Over much of the network more than one route provides service over the same tracks, and these routes all feed into one of three core lines: a central, elevated east-west line (the Stadtbahn), a central, mostly underground north-south line (the Nord-Süd-Tunnel), and a circular, mostly elevated line (the Ringbahn).[18]

The Stadtbahn carries both S-Bahn trains and regional and long-distance trains, on two separate pairs of tracks. This line passes through most of the city's long-distance and regional train stations, including Berlin Zoologischer Garten, Berlin Hauptbahnhof, Friedrichstraße, Alexanderplatz, and Berlin Ostbahnhof. The Ringbahn forms a circle around the inner city and crosses the Stadtbahn at Westkreuz ("west crossing") and Ostkreuz ("east crossing"). The Nord-Süd-Tunnel intersects the Stadtbahn at Friedrichstraße and the Ringbahn at Südkreuz and Gesundbrunnen.[18][19][20]

During the East German era the S-Bahn was run by the communist state, initially even in West Berlin. As a result, and as a protest against the building of the Berlin Wall, the S-Bahn was boycotted by West Berliners, and much of the system in West Berlin eventually closed through lack of traffic. In 1984 (after a 1980 S-Bahn strike in West Berlin) the BVG took over operation of the West Berlin section of the S-Bahn. After reunification, the two halves of the S-Bahn were reunited under the ownership of the Deutsche Bahn.[17] Several of the S-Bahn services shut down due to Berlin partition and the 1980 S-Bahn strike have still not been restored.

Trams

Berlin has a tram network comprising 22 tram lines serving 377 tram stops and measuring 293.78 kilometres (182 mi 44 ch) in length (two single tracks combined). All these services are operated by the Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) and use the common public transport tariff run by the Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg (VBB).[16] The Berlin light rail system is one of the five most extensive in Europe in terms of track lengths.

Of the 22 BVG-operated tram routes, nine are designated as part of the MetroNetz, which provide a high frequency service in areas poorly served by the U-Bahn and S-Bahn. These MetroTram tram lines are recognisable by an M prefix to their route number, and are the only tram routes to operate 24 hours a day.[16]

Berlin's first horse tram opened in 1865, running from Brandenburger Tor to Charlottenburg. In 1881, the world's first electric tramway was opened by Werner von Siemens in Groß-Lichterfelde, now part of Berlin. By 1910, the horse trams had been entirely replaced by electric trams. Historically the trams were operated by several independent companies which were slowly merged in the early twentieth century under the urging of Berlin politician Ernst Reuter and brought into public ownership to form what is today the BVG.

Prior to the division of Berlin, tram lines existed throughout the city, but all the tram lines in the former West Berlin had been replaced by bus or U-Bahn services by 1967. However East Berlin retained its tram lines, and the current network is still predominantly in that area, although there have been a few extensions back across the old border. After reunification tram expansion has been prioritized over U-Bahn expansion and there are plans for a pan-Berlin tram network to cover the entire city.

Besides the BVG tram routes, two further tram lines (numbered 87 and 88) cross the Berlin city boundary in order to connect suburban S-Bahn stations within the city to the Brandenburg towns of Woltersdorf, Schöneiche and Rüdersdorf. A similar line operates within the nearby town of Strausberg, whilst the adjacent city of Potsdam has its own sizable tram network. Whilst none of these lines is operated by the BVG, they all use the VBB common tariff.

Buses

Berlin has a network of 152 daytime bus routes serving 6.589 bus stops and with a total route length of 1.798 kilometres (1.117 mi). All these services are operated by the Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) and use the common public transport tariff run by the Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg (VBB).[16]

Of the BVG-operated bus routes, 19 are designated as part of the MetroNetz, which provides a high frequency service in areas poorly served by the U-Bahn and S-Bahn. Like the MetroTram tram routes, these MetroBus routes can be recognised by an M prefix to their route number. A further 13 BVG-operated bus routes are express routes with an X prefix to their route number.[16]

At nighttime, Berlin is served by a night bus network of 63 bus routes serving 1508 stops and a total route length of 795 kilometres (494 mi). One night bus runs parallel to each U-Bahn line during the weektime closing hours. Most of the MetroNetz bus and tram routes operate 24 hours a day, and form part of both the day and night networks. Again services are operated by BVG and use the VBB tariff.[16]

BVG bus service is provided by a fleet of 1550 buses, of which 145 are double-decker buses, but will be growing to a total of 200. Whilst such buses are common in both Ireland and the United Kingdom, their use elsewhere in Europe is extremely uncommon in regular service.[16]

Ferries

Berlin has an extensive network of waterways within its city boundaries, including the Havel, Spree and Dahme rivers, and many linked lakes and canals. These are crossed by six passenger ferry routes that are operated by the Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) and use the common public transport tariff managed by the Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg (VBB).[21]

There are also a number of other ferry routes that are not managed by BVG, and do not form part of the VBB common tariff. These include passenger and car ferries serving islands within Berlin's lakes, as well as a car ferry across the River Havel. The adjacent city of Potsdam operates a ferry that is within the VBB common tariff.

Cableways

The IGA Cable Car is a 1.5 km (0.93 mi)-long Gondola lift[22] line serving and crossing the Erholungspark Marzahn. Built for the Internationale Gartenausstellung 2017 (IGA 2017), it is the first cableway opened in Berlin.[23][24] It has a separate, more expensive, ticketing scheme from VBB integrated services.

Berlin Public Transportation Statistics

The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Berlin, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 62 min. 15% of public transit riders, ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 10 min, while 10% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 9.1 km (5.7 mi), while 22% travel for over 12 km (7.5 mi) in a single direction.[25]

Airports

Berlin has one commercial international airport: Berlin Brandenburg Airport (BER), located just outside Berlin's south-eastern border in the state of Brandenburg. The airport opened in October 2020 after extensive delays and cost overruns, and replaced Tegel Airport (TXL) and Schönefeld Airport (SXF) as the single commercial airport of Berlin, integrating the existing facilities at Schönefeld Airport.[26] The BER will have an initial capacity of around 35 million passengers per year. Plans for future expansion bringing the terminal capacity to approximately 50 million commuters per year are in development.

Before the opening of Bradenburg Airport, Berlin was served by Tegel Airport and Schönefeld Airport. Tegel Airport was situated within the city limits while Schönefeld Airport was located near the current Bradenburg Airport site. Both airports together handled 29.5 million passengers in 2015. In 2014, 67 airlines served 163 destinations in 50 countries from Berlin.[27] Tegel Airport was focus city airport for Lufthansa and Eurowings and a hub of Air Berlin until its demise in 2017. The military aviation unit (Flugbereitschaft des Bundesministeriums der Verteidigung) of the Federal Republic of Germany was based there as well. Schönefeld served as an important destination for airlines like Germania, easyJet and Ryanair.

Berlin Brandenburg Airport

Following German reunification in 1990, the inefficiency of operating three separate airports became increasingly problematic. Berlin's airport authority (the Berliner Flughafen GmbH, a subsidiary of the Flughafen Berlin-Schönefeld GmbH) transferred all of Berlin's air traffic to a greatly expanded airport at Schönefeld, later renamed Berlin Brandenburg Airport.[28]

The existing airport in Schönefeld was greatly expanded to the south from its current state to allow this. In fact, the new airport only has the current southern runway (the new designated northern runway) in common with the existing airport.

Berlin Brandenburg Airport is predicted to be Germany's third busiest international airport, as Berlin's airports served around 33 million passengers in 2016.[29]

History

The first airport in Berlin was Johannisthal Air Field which opened on 26 September 1909. Followed shortly after by Staaken Airport around 1915, known for its two zeppelin halls and Deutsche Luft Hansa base. Then came Tempelhof Airport in 1923 and Gatow Air Field in 1934. Tegel Airport was built during the Berlin Blockade in 1948.

Tempelhof was the first airport in the world with regular passenger flights, opening in 1923 with flights to Königsberg (now Kaliningrad). Deutsche Luft Hansa started its operations from the airport in 1926, while zeppelins also frequented the airport. The airport expanded rapidly, becoming one of the largest airports in the world in the 1930s, fittingly provided with enormous halls, which are still visible today, unfinished though they may be. Tempelhof also had another first: it was the first airport to feature its own underground station.[30]

Following World War II, Tempelhof was used as a U.S. Air Force base, while the Soviet air force relocated to Schönefeld, outside Berlin, during 1946. The Soviets had reached Tempelhof before the Western Allies. Gatow Air Field, which was taken over by the RAF in July 1945, was partially outside Berlin. At the Potsdam Conference it was then decided to exchange the western half of Staaken, including Staaken Airport, for the needed territory in Gatow.[31] Staaken Airport was then used by the Soviet air force for some time to come.

In April 1948, as a result of growing tension between the Soviet and the Western Allied occupying powers, West Berlin was closed off from the surrounding Soviet sector. Supplies were flown in for over a year; enormous numbers of transport planes flew in and out of Berlin every day of this period. The capacity of the airports then in the three Western sectors was not large enough; to relieve pressure on Gatow and Tempelhof, Tegel Airport was built in the French sector. It was constructed by a labour force mainly consisting of Berlin women [citation needed], under the supervision of French engineers, within just 90 days [citation needed]. It featured a 2400 m runway - the longest in Europe at the time. Because of special Allied bylaws, Lufthansa was not allowed to use Tegel until after German reunification.

Tempelhof was returned to civil administration in 1951, Schönefeld in 1954 and Tegel in 1960. Gatow Airport remained a military airfield, used by the RAF until 1994 and closed in 1995. Tegel, the newest airport, became the main civilian airport for West Berlin, while Schönefeld served the population of East Berlin. Since the smaller airport at Tempelhof is surrounded by urban development, it could not expand.

See also

References

- ^ "Broke but dynamic, Berlin seeks new identity". IHT. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- ^ "Berlin fact sheet" (PDF). berlin.de. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- ^ "Straßenverkehr 2013". Amt für Statistik Belrin Brandenburg (in German). Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ "Spitzenbelastungen auf bundesdeutschen Autobahnen in Berlin, Köln und Frankfurt". The Federal Highway Research Institute. 2007-03-13. Archived from the original on 2010-03-02. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ Taxis fares comparison (2014)

- ^ "Bike City Berlin". Treehugger. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- ^ "Bicycle Routes and Facilities Bicycle Paths" (in German). Senate Department of Urban Development. Archived from the original on 2008-09-22. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ^ ""Mobilität in Städten – System repräsentativer Verkehrsbefragungen (SrV) 2013" - Mobilitätsdaten für Berlin". The Official Website of Berlin. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ ""Mobilität in Städten – System repräsentativer Verkehrsbefragungen (SrV) 2018" - Mobilitätsdaten für Berlin auch bezirksweise". The Official Website of Berlin. 16 August 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Sheffield, Barry (1995). Inland Waterways of Germany. St Ives: Imray Laurie Norie & Wilson. ISBN 0-85288-283-1.

- ^ Gawthrop, John; Williams, Christian (2008). The Rough Guide to Berlin. London - New York City - Delhi: Rough Guides. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-1-85828-382-1.

- ^ "Bahnhof Berlin Hbf Daten und Fakten". Berliner HBF (in German). Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Tickets / Ticket fares". Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- ^ a b "Tickets & Tarife" [Tickets & Fares] (in German). Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- ^ "The Berlin metro (U-Bahn)". Means of Transport & Routes. BVG. Archived from the original on 2007-08-20. Retrieved 2007-09-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Profil | BVG Unternehmen" [Profile | BVG Corporation] (in German). Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe. 2023-06-10. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ^ a b Hardy, Brian (2000). The Berlin S-Bahn Handbook. Capital Transport Publishing. ISBN 1-85414-185-6.

- ^ a b "S-Bahn + U-Bahn Routemap" (PDF). S-Bahn Berlin GmbH. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 29, 2009. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ "Map S-Bahn Stadtbahn". S-Bahn Berlin. Archived from the original on March 14, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ^ "BVG Route planner". Berlin Transport Authority. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ^ "Linien, Netze & Karten - Verkehrsmittel & Linien - Fähre" (in German). BVG. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ IGA Cable Car on gondolaproject.com

- ^ IGA Ropeway (IGA Berlin 2017 website)

- ^ (in German) "The construction of the IGA Cableway has officially begun". Berliner Woche

- ^ "Berlin Public Transportation Statistics". Global Public Transit Index by Moovit. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ "Berlin's new $7 billion airport has finally opened after 9 years of delays, corruption allegations, and construction woes— see inside". Business Insider. Business Insider. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "2014 summer flight schedule". FBB. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "Airport Berlin Brandenburg International". Airports Berlin. Archived from the original on 2008-09-22. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ^ "Die größten Flughäfen Deutschlands bei Rankaholics®". www.rankaholics.de. Archived from the original on 2008-03-02.

- ^ Historic Berlin Airport To Close in 2008 || Jaunted

- ^ "Großbritannien" (in German). Alliierte in Berlin e.V. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

External links

![]() Media related to Transport in Berlin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Transport in Berlin at Wikimedia Commons