Tove Jansson

Tove Jansson | |

|---|---|

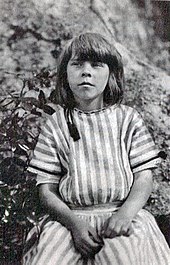

Jansson in 1956 with moomintroll dolls made by Atelier Fauni | |

| Born | Tove Marika Jansson 9 August 1914 Helsinki, Grand Duchy of Finland, Russian Empire |

| Died | 27 June 2001 (aged 86) Helsinki, Finland |

| Occupation | Artist, writer, painter |

| Language | Swedish |

| Nationality | Finnish |

| Notable works | The Moomins The Summer Book |

| Notable awards | Hans Christian Andersen Award 1966 Order of the Smile 1975 Pro Finlandia 1976 |

| Partner | Tuulikki Pietilä |

| Signature | |

Tove Marika Jansson (Swedish pronunciation: [ˈtuːve ˈjɑːnsːon] ; 9 August 1914 – 27 June 2001) was a Swedish-speaking Finnish author, novelist, painter, illustrator and comic strip author. Brought up by artistic parents, Jansson studied art from 1930 to 1938 in Stockholm, Helsinki and Paris. Her first solo art exhibition was held in 1943. Over the same period, she penned short stories and articles for publication, and subsequently drew illustrations for book covers, advertisements, and postcards. She continued her work as an artist and writer for the rest of her life.

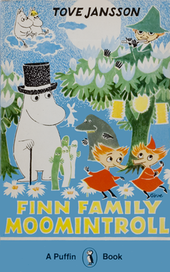

Jansson wrote the Moomin novel series for children, beginning publication in 1945 with the release of The Moomins and the Great Flood. The following two books, Comet in Moominland and Finn Family Moomintroll, published in 1946 and 1948 respectively, were highly successful, and sales of the first book increased correspondingly. For her work as a children's author she received the Hans Christian Andersen Medal in 1966,[1][2] and in 2016 Jansson was included in The Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame.

Starting with the semi-autobiographical Bildhuggarens dotter (Sculptor's Daughter) in 1968, Jansson wrote six novels, including the admired[3] Sommarboken (The Summer Book), and five short story collections for adults.

Early life

Tove Jansson was born in Helsinki, in the Grand Duchy of Finland, a part of the Russian Empire at the time. Her family, part of the Swedish-speaking minority of Finland, was an artistic one: her father, Viktor Jansson, was a sculptor, and her mother, Signe Hammarsten-Jansson, was a Swedish-born graphic designer and illustrator. Tove's siblings also became artists: Per Olov Jansson became a photographer and Lars Jansson an author and cartoonist. Whilst their home was in Helsinki, the family spent many of their summers in a rented cottage on an island near Porvoo, 50 km (31 miles) east of Helsinki;[4] among other things, the Söderskär Lighthouse island off Porvoo in the Gulf of Finland served as an important source of inspiration for her later literature (see Moominpappa at Sea).[5]

Jansson went to Läroverket för gossar och flickor in Helsinki and then studied at University College of Arts, Crafts and Design, in Stockholm in 1930–1933, the Graphic School of the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts in 1933–1937, and finally at L'École d'Adrien Holy and L'École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1938. She displayed a number of artworks in exhibitions during the 1930s and early 1940s, and her first solo exhibition was held in 1943.

At age 14, Jansson wrote and illustrated her first picture book Sara och Pelle och näckens bläckfiskar (Sara and Pelle and Neptune's Children).[6] It was not published until 1933. She also sold drawings that were published in magazines in the 1920s.[7]

During the 1930s Jansson made several trips to other European countries. She drew from these for her short stories and articles, which she also illustrated, and which were also published in magazines, periodicals and daily papers. During this period, Jansson also designed many book covers, adverts and postcards. Following her mother's example, she drew illustrations for Garm, an anti-fascist Finnish-Swedish satirical magazine.[7]

She was briefly engaged in the 1940s to Atos Wirtanen.[7] During her later studies, Jansson met her future partner Tuulikki Pietilä.[8] The two women collaborated on many works and projects, including a model of the Moominhouse, in collaboration with Pentti Eistola. This is now exhibited at the Moomin museum in Tampere.

Work

Moomins

Jansson is principally known as the author of the Moomin books. Jansson created the Moomins, a family of trolls who are white, round and smooth in appearance, with large snouts that make them vaguely resemble hippopotamuses.

The first Moomin book, The Moomins and the Great Flood, was written in 1945. Although the primary characters are Moominmamma and Moomintroll, most of the principal characters of later stories were only introduced in the next book, so The Moomins and the Great Flood is frequently considered a forerunner to the main series. The book was not a success, but the next two installments in the Moomin series, Comet in Moominland (1946) and Finn Family Moomintroll (1948), brought Jansson some fame. The original title of Finn Family Moomintroll, Trollkarlens Hatt, translates as The Magician's Hat.

The style of the Moomin books changed as time went by. The first books, written starting just after the Second World War, up to Moominland Midwinter (1957), are adventure stories that include floods, comets and supernatural events. The Moomins and the Great Flood deals with Moominmamma and Moomintroll's flight through a dark and scary forest, where they encounter various dangers. In Comet in Moominland, a comet nearly destroys the Moominvalley (some critics have considered this an allegory of nuclear weapons[9]). Finn Family Moomintroll deals with adventures brought on by the discovery of a magician's hat. The Exploits of Moominpappa (1950) tells the story of Moominpappa's adventurous youth and cheerfully parodies the genre of memoir. Finally, Moominsummer Madness (1955) pokes fun at the world of the theatre: the Moomins explore an empty theatre and perform Moominpappa's pompous hexametric melodrama.

In addition to the Moomin novels and short stories, Tove Jansson also wrote and illustrated four original and popular picture books: The Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My (1952), Who will Comfort Toffle? (1960), The Dangerous Journey (1977) and An Unwanted Guest (1980). As the Moomins' fame grew, two of the original novels, Comet in Moominland and The Exploits of Moominpappa, were revised by Jansson and republished.

Critics have interpreted various Moomin characters as being inspired by real people, especially members of the author's family, and Jansson spoke in interviews about the backgrounds of, and possible models for, her characters.[7]

Pietilä's personality inspired the character Too-Ticky in Moominland Midwinter[4][7] and Moomintroll and Little My have been seen as psychological self-portraits of the artist.[4][7] Jansson referred to Moomintroll as her alter-ego.[10]

The Moomins, generally speaking, relate strongly to Jansson's own family – they were bohemian and lived close to nature. Jansson remained close to her mother until her mother's death in 1970; even after Tove had become an adult, the two often traveled together, and during her final years Signe also lived with Tove part-time.[7] Moominpappa and Moominmamma are often seen as portraits of Jansson's parents.[4][7][10][11]

Other writing

After Moominvalley in November Tove Jansson stopped writing about Moomins and started writing for adults. Jansson's first foray outside children's literature was Bildhuggarens dotter (Sculptor's Daughter), a semi-autobiographical novel published in 1968. After that, she wrote five more novels, including Sommarboken (The Summer Book) and five collections of short stories. The Summer Book is the best known of her adult fiction translated into English. It is a work of charm, subtlety and simplicity, describing the summer stay on an island of a young girl and her grandmother. The girl is modelled on her niece, Sophia Jansson; the girl's father on Sophia's father, Lars Jansson; and the grandmother on Tove's mother Signe.[3]

Wartime satire in Garm magazine

Tove Jansson worked as an illustrator and cartoonist for the Swedish-language satirical magazine Garm from the 1930s to 1953.[13] One of her political cartoons achieved a brief international fame: she drew Adolf Hitler as a crying baby in diapers, surrounded by Neville Chamberlain and other great European leaders, who tried to calm the baby down by giving it slices of cake – Austria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, etc. In the Second World War, during which Finland fought against the Soviet Union, part of the time cooperating with Nazi Germany,[14] her cover illustrations for Garm lampooned both Hitler and Joseph Stalin: in one, Stalin draws his sword from his impressively long scabbard, only to find it absurdly short; in another, multiple Hitlers ransack a house, carrying away food and artworks. In The Spectator's view, Jansson made Hitler a preposterous little figure, self-important and comic.[12]

Comic strip artist

Jansson also produced illustrations during this period for the Christmas magazines Julen and Lucifer (just as her mother had earlier) as well as several smaller productions. Her earliest comic strips were created for productions including Lunkentus (Prickinas och Fabians äventyr, 1929), Vårbrodd (Fotbollen som Flög till Himlen', 1930), and Allas Krönika (Palle och Göran gå till sjöss, 1933).[15]

The figure of the Moomintroll appeared first in Jansson's political cartoons, where it was used as a signature character near the artist's name. This "Proto-Moomin", then called Snork or Niisku,[7] was thin and ugly, with a long, narrow nose and devilish tail. Jansson said that she had designed the Moomins in her youth: after she lost a philosophical quarrel about Immanuel Kant with one of her brothers, she drew "the ugliest creature imaginable" on the wall of their outhouse and wrote under it "Kant". This Moomin later gained weight and a more pleasant appearance, but in the first Moomin book The Moomins and the Great Flood (originally Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen), the Immanuel-Kant-Moomin is still perceptible. The name Moomin comes from Tove Jansson's uncle, Einar Hammarsten: when she was studying in Stockholm and living with her Swedish relatives, her uncle tried to stop her pilfering food by telling her that a "Moomintroll" lived in the kitchen closet and breathed cold air down people's necks.[7]

In 1952, after Comet in Moominland and Finn Family Moomintroll had been translated into English, a British publisher asked if Tove Jansson would be interested in drawing comic strips about the Moomins. Jansson had already drawn a long Moomin comic adventure, Mumintrollet och jordens undergång (Moomintroll and the End of the World), based loosely on Comet in Moominland, for the Swedish-language newspaper Ny Tid, and she accepted the offer. The comic strip Moomintroll, started in 1954 in the London Evening News. Tove Jansson drew 21 long Moomin stories from 1954 to 1959, writing them at first by herself and then with her brother Lars Jansson. She eventually gave the strip up because the daily work of a comic artist did not leave her time to write books and paint, but Lars took over the strip and continued it until 1975.

The series was published in book form in Swedish; books 1 to 6 have been published in English, Moomin: The Complete Tove Jansson Comic Strip.

Painter and illustrator

Although she became known first and foremost as an author, Tove Jansson considered her careers as author and painter to be of equal importance. She painted her whole life, changing style from the classical impressionism of her youth to the highly abstract modernist style of her later years. Jansson displayed a number of artworks in exhibitions during the 1930s and early 1940s, and her first solo exhibition was held in 1943. Despite generally positive reviews, criticism induced Jansson to refine her style such that in her 1955 solo exhibition her style had become less overloaded in terms of detail and content. Between 1960 and 1970 Jansson held five more solo exhibitions.[7]

Jansson also created a series of commissioned murals and public works throughout her career, which may still be viewed in their original locations. These works of Jansson's included:

- The canteen at the Strömberg factory at Pitäjänmäki, Helsinki (1945)[7]

- The Aurora Children's Hospital in Helsinki[4]

- The Kaupunginkellari restaurant of Helsinki City Hall[4] – Transferred in 1974 to Helsinki Swedish-language Adult Education Centre "Workers' Institute" Arbis and in 2016 to a permanent Jansson exhibition at Helsinki Art Museum[16]

- The Seurahuone hotel at Hamina[7]

- The Wise and Foolish Virgins altarpiece in Teuva Church (1954)[7]

- A number of fairy-tale murals in schools and kindergartens including the kindergarten in Pori (1984)[7]

In addition to providing the illustrations for her own Moomin books, Jansson also illustrated Swedish translations of classics such as J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit[17] and Lewis Carroll's The Hunting of the Snark[18] and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland[19] (some used later in Finnish translations as well). She also illustrated her late work, The Summer Book (1972).

Theatre

Several stage productions have been made from Jansson's Moomin series, including a number that Jansson herself was involved in.

The earliest production was a 1949 theatrical version of Comet in Moominland performed at Åbo Svenska Teater.[7]

In the early 1950s, Jansson collaborated on Moomin-themed children's plays with Vivica Bandler. In 1952, Jansson designed stage settings and dresses for Pessi and Illusia, a ballet by Ahti Sonninen (Radio tekee murron) which was performed at the Finnish National Opera.[7] By 1958, Jansson began to become directly involved in theater as Lilla Teater produced Troll i kulisserna (Troll in the wings), a play with lyrics by Jansson and music composed by Erna Tauro. The production was a success, and later performances were held in Sweden and Norway.[4]

In 1974 the first Moomin opera was produced, with music composed by Ilkka Kuusisto.[4]

Personal life

Jansson had several male lovers, including the political philosopher Atos Wirtanen, who was the inspiration for the Moomin character Snufkin. However, she eventually "went over to the spook side" as she put it—a coded expression for homosexuality[20][21][22][23]—and developed a secret love affair with the married theater director Vivica Bandler.[24]

In 1956 Jansson met her lifelong partner, Tuulikki Pietilä – or "Tooti", as she was known. In Helsinki they lived separately, in neighbouring blocks, visiting each other privately through an attic passageway. In the 1960s, they built a house on a tiny uninhabited island in the Gulf of Finland, 100 kilometres (62 mi) from Helsinki, where they would escape for the summer months.[25] Jansson's and Pietilä's travels and summers spent together on the Klovharu island in Pellinki have been captured on several hours of film, shot by Pietilä. Several documentaries have been made of this footage, the latest being Haru, yksinäinen saari (Haru, the lonely island) (1998)[26] and Tove ja Tooti Euroopassa (Tove and Tooti in Europe) (2004).[27] It is speculated that the character Too-ticky, a wise human who wears a red striped shirt and carries a briefcase, was inspired by Pietilä.[24]

Jansson died on 27 June 2001 at the age of 86 from cancer. She is buried with her parents and younger brother, Lars, at the Hietaniemi Cemetery in Helsinki.[21][28][29][30][31]

Family

- Viktor Jansson (born 1829) married Ida Maria Lemström (born 1842)

- Julius Viktor Jansson (1862–1892) married Johanna Theresia Karlsson (1864–1938)

- Viktor Bernhard Jansson (1886–1958) married Signe Hammarsten (1882–1970)

- Tove Marika Jansson (1914–2001), intimate partnership with Tuulikki "Tooti" Pietilä (1956–until death)[32][a]

- Per Olov Jansson (1920–2019)

- Lars Jansson (1926–2000)

- Vivica Sophia Jansson (born 1962) married ______ Zambra

- James Zambra (born 1989)

- Thomas Zambra (born 1992)[33]

- Vivica Sophia Jansson (born 1962) married ______ Zambra

- Julius Edvard Jansson (born 1887) married Toini Maria Ilmonen

- Viktor Bernhard Jansson (1886–1958) married Signe Hammarsten (1882–1970)

- Julius Viktor Jansson (1862–1892) married Johanna Theresia Karlsson (1864–1938)

Cultural legacy

The biennial Hans Christian Andersen Award conferred by the International Board on Books for Young People is the highest recognition available to a writer or illustrator of children's books. Jansson received the writing award in 1966.[1][2]

In 1968, Swedish public TV, SVT, made a documentary about Tove called Moomins and the Harbor (39 min.).[34]

Jansson's books, originally written in Swedish, have been translated into 45 languages.[36] After the Kalevala and books by Mika Waltari, they are the most widely translated works of Finnish literature.

The Moomin Museum in Tampere displays much of Jansson's work on the Moomins. There is also a Moomin theme park named Moomin World in Naantali.

Tove Jansson was selected as the main motif in the 2004 minting of a Finnish commemorative coin, the €10 Tove Jansson and Finnish Children's Culture commemorative coin. The obverse depicts a combination of Tove Jansson portrait with several objects: the skyline, an artist's palette, a crescent and a sailing boat. The reverse design features three Moomin characters. In 2014 she was again featured on a commemorative coin, minted at €10 and €20 values, being the only person other than the former Finnish president Urho Kekkonen to be granted two such coins.[37] She was also featured on a €2 commemorative coin that entered general circulation in June 2014.[38]

Since 1988, Finland's Post has released several postage stamp sets and one postal card with Moomin motifs.[39] In 2014, Jansson herself was featured on a Finnish stamp set.[40]

In 2014 the City of Helsinki honored Jansson by renaming a park in Katajanokka as Tove Jansson's Park (Finnish: Tove Janssonin puisto, Swedish: Tove Janssons park). The park is located near Jansson's childhood home.[41][42]

In March 2014, the Ateneum Art Museum opened a major centenary exhibition showcasing Jansson's works as an artist, an illustrator, a political caricaturist and the creator of the Moomins. The exhibition drew nearly 300,000 visitors in six months.[43] After Helsinki the exhibition embarked on a tour in Japan to visit five Japanese museums.[44][45]

In 2012, the BBC broadcast a one-hour documentary on Jansson, Moominland Tales: The Life of Tove Jansson.[46]

From October 2017 to January 2018, the Dulwich Picture Gallery held an exhibition of Jansson's paintings, illustrations, and cartoons.[47] This was the first major retrospective exhibition of her work in the United Kingdom.[35]

With a new animated series, Moominvalley[48] broadcast in 2019, Rhianna Pratchett wrote an article about the impact Tove Jansson had had on her father Sir Terry Pratchett; he called Jansson one of the greatest children's writers there has ever been and credited her writing as one of the reasons he became an author.[49]

A biopic, titled Tove, directed by Zaida Bergroth was released in October 2020.[50]

Bibliography

The Moomin books

Novels

- Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (1945, The Moomins and the Great Flood)

- Kometjakten (1946, Comet in Moominland)

- Kometen kommer (1968; reworked edition of Comet in Moominland)

- Trollkarlens hatt (1948, Finn Family Moomintroll; in some editions The Happy Moomins)

- Muminpappans bravader (1950, The Exploits of Moominpappa)

- Muminpappans memoarer (1968, The Memoirs of Moominpappa; reworked edition of The Exploits of Moominpappa)

- Farlig midsommar (1954, Moominsummer Madness)

- Trollvinter (1957, Moominland Midwinter)

- Pappan och havet (1965, Moominpappa at Sea)

- Sent i november (1970, Moominvalley in November)

Short story collections

- Det osynliga barnet och andra berättelser (1962, Tales from Moominvalley)

Picture books

- Hur gick det sen? (1952, The Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My)

- Vem ska trösta Knyttet? (1960, Who Will Comfort Toffle?)

- Den farliga resan (1977, The Dangerous Journey)

- Skurken i Muminhuset (1980, Villain in the Moominhouse)

- Visor från Mumindalen (1993, Songs From Moominvalley; songbook. With Lars Jansson and Erna Tauro)

Comic strips

- Mumin, Books 1–7 (1977–1981, Moomin; Books 3–7 with Lars Jansson) (Books 1–6 released in English).[51]

Other books

Novels

- Sommarboken (1972, The Summer Book)

- Solstaden (1974, Sun City)

- Den ärliga bedragaren (1982, The True Deceiver)

- Stenåkern (1984, The Field of Stones)

- Rent spel (1989, Fair Play)

Short story collections

- Bildhuggarens dotter (1968, Sculptor's Daughter) (semi-autobiographical)

- Lyssnerskan (1971, The Listener)

- Dockskåpet och andra berättelser (1978, lit. "The Doll's House and Other Stories", translated as Art in Nature)

- Resa med lätt bagage (1987, Travelling Light)

- Brev från Klara och andra berättelser (1991, Letters from Klara and Other Stories)

- Meddelande. Noveller i urval 1971–1997 (1998 compilation, Messages: Selected Stories 1971–1997)

- A Winter Book (Sort of Books, 2006). Selected and introduced by Ali Smith, from Sculptor's Daughter, Messages, The Listener, Letters from Klara, and Traveling Light.

- The Woman Who Borrowed Memories (New York Review Books, 2014). Selections from The Listener, The Doll's House, Traveling Light, Letters from Klara, and Messages. Translated by Thomas Teal and Silvester Mazzarella.

Miscellaneous

- Sara och Pelle och näckens bläckfiskar (under the pseudonym of Vera Haij, 1933, Sara and Pelle and the Octopuses of the Water Sprite)

- Anteckningar från en ö (1993, Notes from an Island; autobiography; illustrated by Tuulikki Pietilä)

- Letters from Tove (2019) (personal letters written by Tove, edited by Boel Westin and Helen Svensson)

Awards

- Hans Christian Andersen Award (gold medal, 1966)[52]

- Award for State Literature (1963, 1971 and 1982)[4]

- Swedish Academy Finland Prize (1972)

- Order of the Smile (1975)

- Pro Finlandia Medal (1976)[4]

- Swedish Culture Foundation Honorary Award (1983)[53]

- The Finnish Cultural Award (1990)[53]

- Selma Lagerlöf Prize (1992)[53]

- The Finland Art Prize (1993)[53]

- Mercuri International pronssiomena (1994)[53]

- The Swedish Academy Award (1994)[53]

- The American-Scandinavian Foundation Honorary Cultural Award (1996)[53]

- WSOY Literary Foundation Award (1999)[53]

- Le Prix de l'Office Chrétien du Livre [53]

See also

Notes

- ^ Same-sex marriage was not legalized in Finland until 2017.

References

- ^ a b "Hans Christian Andersen Awards". International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY). Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ^ a b

"Tove Jansson" (pp. 32–33, by Sus Rostrup).

The Hans Christian Andersen Awards, 1956–2002. IBBY. Gyldendal. 2002. Hosted by Austrian Literature Online. Retrieved 2013-08-01. - ^ a b Westin, Boel (2013). Tove Jansson - Ord, bild, liv (in Swedish). Albert Bonniers. ISBN 978-9-51-501672-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Liukkonen, Petri. "Tove Jansson". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008.

- ^ "Söderskär Lighthouse". Helsinki This Week. 3 July 2019.

- ^ "ArchWay With Words". ArchWayWithWords.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Ahola, Suvi (2008). "Jansson, Tove (1914–2001)". Biografiakeskus. Translated by Fletcher, Roderick. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ Hassel, Ing-Marie. "Tove Janssons mumintroll" (in Swedish). Retrieved 9 April 2007.

- ^ Schoolfield, George C. (1998). A history of Finland's literature. University of Nebraska Press. p. 572. ISBN 978-0-8032-4189-3.

- ^ a b Karjalainen, Tuula (2014). Tove Jansson. Work and Love. Penguin UK. ISBN 9781846148491.

- ^ Rahunen, Suvi (Spring 2007). Om Översättning av Kulturbunda Element från Svenska till Finska och Franska i Två Muminböcker av Tove Jansson [About Translation of Culturally Based Elements from Swedish to Finnish and French in Two Moomin Books by Tove Jansson] (Thesis). University of Jyväskylä. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ^ a b McDonagh, Melanie (18 November 2017). "A chance to see the Moomins' creator for the genius she really was: Tove Janssons reviewed". The Spectator (November 2017).

- ^ Ant O’Neill (2017). "Moominvalley Fossils: Translating the Early Comics of Tove Jansson". Bookbird: A Journal of International Children's Literature. 55 (2): 52. doi:10.1353/bkb.2017.0023. ISSN 0006-7377. S2CID 151535137.

- ^ Taylor, Alan (23 May 2013). "Finland in World War II". The Atlantic. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ "Comic creator: Tove Jansson". lambiek.net. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ "Tove Jansson". Helsinki Art Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ "Hobbit illustrations". 20 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2014 – via Flickr.

- ^ "Hunting of the Snark illustrations". 20 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2014 – via Flickr.

- ^ "Alice in Wonderland illustrations". 20 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2014 – via Flickr.

- ^ "Mamma of all the Moomins". Evening Standard. 9 January 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ a b Prideaux, Sue (15 January 2014). "Tove Jansson: Life, Art, Words by Boel Westin – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ "The Gay Love Stories of Moomin and the Queer Radicality of Tove Jansson". Autostraddle. 3 October 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ Vanderhooft, JoSelle (2 May 2010). "Tove Jansson: Out of the Closet". Tor.com. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ a b Frank, Priscilla (14 September 2017). "Meet The Queer, Anti-Fascist Woman Behind The Freakishly Lovable 'Moomins'". HuffPost. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ Scott, Izabella (May 2018). "The Party" (PDF). So It Goes (11).

- ^ Haru: The Island of the Solitary at IMDb

- ^ Tove ja Tooti Euroopassa at IMDb

- ^ "Famous Deaths for Year 2001 (Part 2)". HistoryOrb.com. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ "Hietaniemen hautausmaa – merkittäviä vainajia" [Hietaniemi Cemetery - significant deceased] (PDF). Helsingin seurakuntayhtymä. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ The Life of Tove Jansson, BBC Scotland documentary

- ^ "Tove Jansson 1914–2001". BillionGraves Record.

- ^ Heti, Seila (30 March 2020). "Inside Tove Jansson's Private Universe". The New Yorker.

In 1956, [Jansson] met Tuulikki Pietilä ("Tooti"), a prolific graphic artist and engraver. They would remain partners for forty-five years, until Jansson's death. But, as Westin and Svensson put it, "anyone who lived with Tove Jansson also had to live with her family". Her mother, nicknamed Ham, stayed with Jansson on and off. Even as a teenager, preparing to go away to school, Jansson had worried about her mother. In a letter from 1961, she describes the stress of managing both Tooti and Ham in their "all-female household." She felt that it had become impossible to please one without displeasing the other, and during a time of intense strife she wrote to a friend, "Sometimes I think I hate them both and it makes me feel ill".

- ^ Saarinen, Riitta (23 June 2021). "Muumien matkassa". Perheyritys-lehti.

- ^ Mumin och havet [Moomins and the Harbor] (in Swedish), archived from the original on 6 April 2015, retrieved 15 March 2019

- ^ a b Kennedy, Maev (22 October 2017). "Moomins and more: UK show to exhibit Tove Jansson's broader work". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ Hällsten, Annika (22 January 2014). "Boksuccé efterlyses". Hufvudstadsbladet. p. 21.

- ^ "Another collector coin is minted in honour of Tove Jansson". Mint of Finland. 30 January 2014. Archived from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Tove Jansson to feature on two-euro commemorative coin". Mint of Finland. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 13 June 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Norma Suomi 2011: Postimerkkiluettelo, pp. 147, 152, 169, 180, 195, 202, 219, 233. [Stamp catalogue.] Käpylän merkki, Helsinki 2010. ISSN 0358-1225

- ^ "The first stamps of 2014 celebrate Tove Jansson and ancient castles". Posti Group. 16 October 2013. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Tove Jansson saa puiston Katajanokalle" [Tove Jansson gets a park in Katajanokka]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). 11 March 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ "Katajanokanpuisto renamed Tove Jansson Park". Finland Times. 12 March 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ "The Tove Jansson centenary exhibition attracted 293,837 visitors". Ateneum Art Museum. 7 September 2014. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ "Tove Jansson 14.03.2014 – 07.09.2014". Ateneum Art Museum. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Ei vain muumien äiti – Tove Janssonilla oli taiteilijana sadat kasvot" [Not just the mother of the moomins – Tove Jansson had hundreds of faces as an artist] (in Finnish). Yle Uutiset. 13 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ "BBC Four - Moominland Tales: The Life of Tove Jansson". BBC.

- ^ "Tove Jansson (1914-2001)". Dulwich Picture Gallery. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "All-star cast for new Moomin animation series, Moominvalley". Moomin.com. 12 September 2017.

- ^ Pratchett, Rhianna (12 March 2018). "My family and other Moomins: Rhianna Pratchett on her father's love for Tove Jansson". The Guardian.

- ^ "New feature drama film about Tove Jansson to premiere in 2020". Moomin.com. 18 June 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "Products by Tove Jansson". Drawn & Quarterly. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ "People – Tove Jansson". thisisFINLAND. 11 March 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Engholm, Ahrvid (8 March 2015). "The Fanzines of Moonin's Mother Tove Jansson - Ahrvid Engholm (Sweden)". Europa SF. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

Further reading

- Gravett, Paul (2022). Tove Jansson. The Illustrators. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-09433-4.

External links

- Tove Jansson at www.moomin.com (in Finnish, Swedish, and English)

- Tove Jansson at Schildts (in Finnish and Swedish)

- Tove Jansson and the altarpiece "Ten Virgins" (in Finnish, Swedish, English, and Japanese)

- Tove Jansson at WSOY (in Finnish)

- thisisFINLAND: People – Tove Jansson: writer, painter and illustrator

- The Moomin Trove Comprehensive lists of Tove Jansson's Moomin books

- Tove Jansson and The Moomin Trove by Finland Travel Club

- Moominland Tales: The Life of Tove Jansson (BBC) by Eleanor Yule

- Tove Jansson at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Tove Jansson at Library of Congress, with 91 library catalogue records

- Jansson, Tove (1914–2001) at National Biography of Finland

- "Tove Jansson". Biografiskt lexikon för Finland (in Swedish). Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. urn:NBN:fi:sls-4317-1416928956923.

- 1914 births

- 2001 deaths

- Tove Jansson

- Writers from Helsinki

- People from Uusimaa Province (Grand Duchy of Finland)

- Finnish writers in Swedish

- Writers from Uusimaa

- Finnish comic strip cartoonists

- Finnish children's writers

- Finnish comics artists

- Finnish fantasy writers

- Finnish women illustrators

- Finnish women short story writers

- Finnish short story writers

- Finnish women novelists

- Finnish people of Swedish descent

- Konstfack alumni

- Bisexual novelists

- Bisexual painters

- Bisexual women artists

- Bisexual women writers

- LGBT comics creators

- Finnish LGBT novelists

- Finnish LGBT painters

- Finnish bisexual people

- Moomins

- Tolkien artists

- Finnish female comics artists

- Female comics writers

- Writers who illustrated their own writing

- Hans Christian Andersen Award for Writing winners

- Selma Lagerlöf Prize winners

- Finnish children's book illustrators

- Women science fiction and fantasy writers

- Finnish women children's writers

- Swedish-speaking Finns

- 20th-century Finnish novelists

- 20th-century Finnish women writers

- 20th-century Finnish women artists

- 20th-century Finnish LGBT people

- Artists from Helsinki

- 20th-century short story writers

- Burials at Hietaniemi Cemetery

- Finnish painters

- Modern painters

- Deaths from cancer in Finland