Environmental health

| Part of a series on |

| Public health |

|---|

|

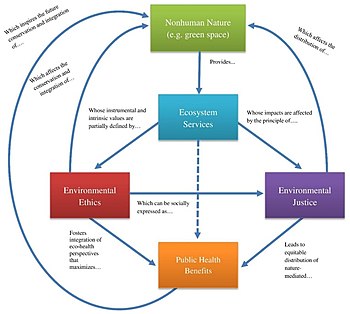

Environmental health is the branch of public health concerned with all aspects of the natural and built environment affecting human health. In order to effectively control factors that may affect health, the requirements that must be met in order to create a healthy environment must be determined.[1] The major sub-disciplines of environmental health are environmental science, toxicology, environmental epidemiology, and environmental and occupational medicine.[2]

Definitions

WHO definitions

Environmental health was defined in a 1989 document by the World Health Organization (WHO) as: Those aspects of human health and disease that are determined by factors in the environment.[3][4] It is also referred to as the theory and practice of accessing and controlling factors in the environment that can potentially affect health.[5]

A 1990 WHO document states that environmental health, as used by the WHO Regional Office for Europe, "includes both the direct pathological effects of chemicals, radiation and some biological agents, and the effects (often indirect) on health and well being of the broad physical, psychological, social and cultural environment, which includes housing, urban development, land use and transport."[6]

As of 2016[update], the WHO website on environmental health states that "Environmental health addresses all the physical, chemical, and biological factors external to a person, and all the related factors impacting behaviours. It encompasses the assessment and control of those environmental factors that can potentially affect health. It is targeted towards preventing disease and creating health-supportive environments. This definition excludes behaviour not related to environment, as well as behaviour related to the social and cultural environment, as well as genetics."[7]

The WHO has also defined environmental health services as "those services which implement environmental health policies through monitoring and control activities. They also carry out that role by promoting the improvement of environmental parameters and by encouraging the use of environmentally friendly and healthy technologies and behaviors. They also have a leading role in developing and suggesting new policy areas."[8][9]

Other considerations

The term environmental medicine may be seen as a medical specialty, or branch of the broader field of environmental health.[10][11] Terminology is not fully established, and in many European countries they are used interchangeably.[12]

Children's environmental health is the academic discipline that studies how environmental exposures in early life—chemical, nutritional, and social—influence health and development in childhood and across the entire human life span.[13]

Other terms referring to or concerning environmental health include environmental public health and health protection.[14]

Disciplines

Five basic disciplines generally contribute to the field of environmental health: environmental epidemiology, toxicology, exposure science, environmental engineering, and environmental law. Each of these five disciplines contributes different information to describe problems and solutions in environmental health. However, there is some overlap among them.

- Environmental epidemiology studies the relationship between environmental exposures (including exposure to chemicals, radiation, microbiological agents, etc.) and human health. Observational studies, which simply observe exposures that people have already experienced, are common in environmental epidemiology because humans cannot ethically be exposed to agents that are known or suspected to cause disease. While the inability to use experimental study designs is a limitation of environmental epidemiology, this discipline directly observes effects on human health rather than estimating effects from animal studies.[15] Environmental epidemiology is the study of the effect on human health of physical, biologic, and chemical factors in the external environment, broadly conceived. Also, examining specific populations or communities exposed to different ambient environments, Epidemiology in our environment aims to clarify the relationship that exist between physical, biologic or chemical factors and human health.[16]

- Toxicology studies how environmental exposures lead to specific health outcomes, generally in animals, as a means to understand possible health outcomes in humans. Toxicology has the advantage of being able to conduct randomized controlled trials and other experimental studies because they can use animal subjects. However, there are many differences in animal and human biology, and there can be a lot of uncertainty when interpreting the results of animal studies for their implications for human health.[17]

- Exposure science studies human exposure to environmental contaminants by both identifying and quantifying exposures. Exposure science can be used to support environmental epidemiology by better describing environmental exposures that may lead to a particular health outcome, identify common exposures whose health outcomes may be better understood through a toxicology study, or can be used in a risk assessment to determine whether current levels of exposure might exceed recommended levels. Exposure science has the advantage of being able to very accurately quantify exposures to specific chemicals, but it does not generate any information about health outcomes like environmental epidemiology or toxicology.[18]

- Environmental engineering applies scientific and engineering principles for protection of human populations from the effects of adverse environmental factors; protection of environments from potentially deleterious effects of natural and human activities; and general improvement of environmental quality.[19]

- Environmental law includes the network of treaties, statutes, regulations, common and customary laws addressing the effects of human activity on the natural environment.[20][21]

Information from epidemiology, toxicology, and exposure science can be combined to conduct a risk assessment for specific chemicals, mixtures of chemicals or other risk factors to determine whether an exposure poses significant risk to human health (exposure would likely result in the development of pollution-related diseases). This can in turn be used to develop and implement environmental health policy that, for example, regulates chemical emissions, or imposes standards for proper sanitation.[22][page needed] Actions of engineering and law can be combined to provide risk management to minimize, monitor, and otherwise manage the impact of exposure to protect human health to achieve the objectives of environmental health policy.

Concerns

Environmental health addresses all human-health-related aspects of the natural environment and the built environment. Environmental health concerns include:

- Biosafety.

- Disaster preparedness and response.

- Food safety, including in agriculture, transportation, food processing, wholesale and retail distribution and sale.

- Housing, including substandard housing abatement and the inspection of jails and prisons.

- Childhood lead poisoning prevention.

- Land use planning, including smart growth.

- Liquid waste disposal, including city waste water treatment plants and on-site waste water disposal systems, such as septic tank systems and chemical toilets.

- Medical waste management and disposal.

- Occupational health and industrial hygiene.

- Radiological health, including exposure to ionizing radiation from X-rays or radioactive isotopes.

- Recreational water illness prevention, including from swimming pools, spas and ocean and freshwater bathing places.

- Solid waste management, including landfills, recycling facilities, composting and solid waste transfer stations.

- Toxic chemical exposure whether in consumer products, housing, workplaces, air, water or soil.

- Vector control, including the control of mosquitoes, rodents, flies, cockroaches and other animals that may transmit pathogens.

According to recent estimates, about 5 to 10% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost are due to environmental causes in Europe. By far the most important factor is fine particulate matter pollution in urban air.[26] Similarly, environmental exposures have been estimated to contribute to 4.9 million (8.7%) deaths and 86 million (5.7%) DALYs globally.[27] In the United States, Superfund sites created by various companies have been found to be hazardous to human and environmental health in nearby communities. It was this perceived threat, raising the specter of miscarriages, mutations, birth defects, and cancers that most frightened the public.[28]

Air quality

Air quality includes ambient outdoor air quality and indoor air quality. Large concerns about air quality include environmental tobacco smoke, air pollution by forms of chemical waste, and other concerns.

Outdoor air quality

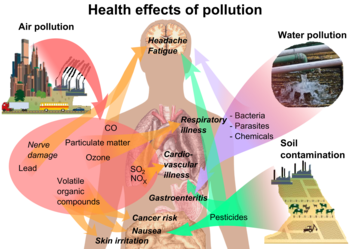

Air pollution is globally responsible for over 6.5 million deaths each year.[29] Air pollution is the contamination of an atmosphere due to the presence of substances that are harmful to the health of living organisms, the environment or climate.[30] These substances concern environmental health officials since air pollution is often a risk-factor for diseases that are related to pollution, like lung cancer, respiratory infections, asthma, heart disease, and other forms of respiratory-related illnesses.[31] Reducing air pollution, and thus developing air quality, has been found to decrease adult mortality.[32]

Common products responsible for emissions include road traffic, energy production, household combustion, aviation and motor vehicles, and other forms of pollutants.[33][34] These pollutants are responsible for the burning of fuel, which can release harmful particles into the air that humans and other living organisms can inhale or ingest.[35]

Air pollution is associated with adverse health effects like respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, cancer, related illnesses, and even death.[36] The risk of air pollution is determined by the pollutant's hazard and the amount of exposure that affects a person.[37] For example, a child who plays outdoor sports will have a higher likelihood of outdoor air pollution exposure compared to an adult who tends to spend more time indoors, whether at work or elsewhere.[37] Environmental health officials work to detect individuals who are at higher risks of consuming air pollution, work to decrease their exposure, and detect risk factors present in communities.[38]

Indoor air quality

Household air pollution contributes to diseases that kill almost 4.3 million people every year.[39] Indoor air pollution contributes to risk factors for diseases like heart disease, pulmonary disease, stroke, pneumonia, and other associated illnesses.[39] For vulnerable populations who spend large amounts of their time indoors, such as children and elderly populations, poor indoor air quality can be dangerous.[40]

Burning fuels like coal or kerosene inside homes can cause dangerous chemicals to be released into the air.[39] Dampness and mold in houses can cause diseases as well, but little studies have been performed on mold in schools and workplaces.[41] Environmental tobacco smoke is considered to be a leading contributor to indoor air pollution, since exposure to second and third-hand smoke is a common risk factor.[42] Tobacco smoke contains over 60 carcinogens, where 18% are known human carcinogens.[43] Exposure to these chemicals can lead to exacerbation of asthma, development of cardiovascular diseases, cardiopulmonary diseases, and increase the likelihood of cancer development.[44]

Climate change and its effects on health

Climate change makes extreme weather events more likely, including ozone smog events, dust storms, and elevated aerosol levels, all due to extreme heat, drought, winds, and rainfall.[45][46] These extreme weather events can increase the likelihood of undernutrition, mortality, food insecurity, and climate-sensitive infectious diseases in vulnerable populations.[47] The effects of climate change are felt by the whole world, but disproportionately affect disadvantaged populations who are subject to climate change vulnerability.[48]

Climate impacts can affect exposure to water-borne pathogens through increased rates of runoff, frequent heavy rains, and the effects of severe storms.[49] Extreme weather events and storm surges can also exceed the capacity of water infrastructure, which can increase the likelihood that populations will be exposed to these contaminants.[49][50] Exposure to these contaminants are more likely in low-income communities, where they have inadequate infrastructure to respond to climate disasters and are less likely to recover from infrastructure damage as quickly.[51]

Problems like the loss of homes, loved ones, and previous ways of life, are often what people face after a climate disaster occurs. These events can lead to vulnerability in the form of housing affordability stress, lower household income, lack of community attachment, grief, and anxiety around another disaster occurring.[48]

Environmental racism

Certain groups of people can be put at a higher risk for environmental hazards like air, soil and water pollution. This often happens due to marginalization, economic and political processes, and racism. Environmental racism uniquely affects different groups globally, however generally the most marginalized groups of any region are affected. These marginalized groups are frequently put next to pollution sources like major roadways, toxic waste sites, landfills, and chemical plants.[52] In a 2021 study, it was found that racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States are exposed to disproportionately high levels of particulate air pollution.[53] Racial housing policies that exist in the United States continue to exacerbate racial minority exposure to air pollution at a disproportionate rate, even as overall pollution levels have declined.[53] Likewise, in a 2022 study, it was shown that implementing policy changes that favor wealth redistribution could double as climate change mitigation measures.[54] For populations who are not subject to wealth redistribution measures, this means more money will flow into their communities while climate effects are mitigated.[53][54]

Noise pollution

Noise pollution is usually non-environmental, machine-created sound that can disrupt activities or communication between humans and other life forms.[55] Exposure to persistent noise pollution can cause diseases like hearing impairment, sleep disturbances, cardiovascular problems, annoyance, problems with communication and other diseases.[56] For American minorities that live in neighborhoods of low socioeconomic status, they often experience higher levels of noise pollution compared to their higher socioeconomic counterparts.[57]

Noise pollution can cause or exacerbate cardiovascular diseases, which can further affect a large range of diseases, increase stress levels, and cause sleep disturbances.[57] Noise pollution is also responsible for cases of hearing loss, tinnitus, and other forms of hypersensitivity or lack thereof to sound.[57] These conditions can be dangerous to children and young adults who consistently experience noise pollution, as many of these conditions can develop into long-term problems.[57]

Children who attend school in noisy traffic zones have shown to have 20% lower memory development compared to other students who attended schools in quiet traffic zones, according to a Barcelona study.[58] This is consistent with research that suggests that children who are exposed to regular aircraft noise "have poorer performance on standardised achievement tests."[59]

Exposure to persistent noise pollution can cause one to develop hearing impairments, like tinnitus or impaired speech discrimination.[60] One of the largest factors in worsened mental health due to noise pollution is annoyance.[61][62] Annoyance due to environmental factors has been found to increase stress reactions and overall feelings of stress among adults.[63] The level of annoyance felt by an individual varies, but contributes to worsened mental health significantly.[62]

Noise exposure also contributes to sleep disturbances, which can cause daytime sleepiness and an overall lack of sleep, which contributes to worsened health.[64][62]

Safe drinking water

Access to safe drinking water is considered a "basic human need for health and well-being" by the United Nations.[65] According to their reports, over 2 billion people worldwide live without access to safe drinking water.[66] In 2017, almost 22 million Americans drank from water systems that were in violation of public health standards.[67] Globally, over 2 billion people drink feces-contaminated water, which poses the greatest threat to drinking water safety.[68] Contaminated drinking water could transmit diseases like cholera, dysentery, typhoid, diarrhea and polio.[68]

Harmful chemicals in drinking water can negatively affect health. Unsafe water management practices can increase the prevalence of water-borne diseases and sanitation-related illnesses.[69][70] Schools in the United States are not required by law to test for safe drinking water, meaning that many children can drink contaminants like lead in their water at school.[71][51] Inadequate disinfecting of wastewater in industrial and agricultural centers can also infect hundreds of millions of people with contaminated water.[68] Chemicals like fluoride and arsenic can benefit humans when the levels of these chemicals are controlled;but other, more dangerous chemicals like lead and metals can be harmful to humans.[68]

In America, communities of color can be subject to poor-quality water.[72] In communities in America with large hispanic and black populations, there is a correlated rise in SDWA health violations.[72] Populations who have experienced lack of safe drinking water, like populations in Flint, Michigan, are more likely to distrust tap water in their communities.[51] Populations to experience this are commonly low-income, communities of color.[73]

Hazardous materials management

Hazardous materials management, including hazardous waste management, contaminated site remediation, the prevention of leaks from underground storage tanks and the prevention of hazardous materials releases to the environment and responses to emergency situations resulting from such releases. When hazardous materials are not managed properly, waste can pollute nearby water sources and reduce air quality.[74]

According to a study done in Austria, people who live near industrial sites are "more often unemployed, have lower educations levels, and are twice as likely to be immigrants.[75] With the interest of environmental health in mind, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act was passed in the United States in 1976 that covered how to properly manage hazardous waste.[76]

Microplastic pollution

Soil pollution

Contaminated or polluted soil directly affects human health through direct contact with soil or via inhalation of soil contaminants that have vaporized; potentially greater threats are posed by the infiltration of soil contamination into groundwater aquifers used for human consumption, sometimes in areas apparently far removed from any apparent source of above-ground contamination. Toxic metals can also make their way up the food chain through plants that reside in soils containing high concentrations of heavy metals.[77] This tends to result in the development of pollution-related diseases.

Most exposure is accidental, and exposure can happen through:[78]

- Ingesting dust or soil directly

- Ingesting food or vegetables grown in contaminated soil or with foods in contact with contaminants

- Skin contact with dust or soil

- Vapors from the soil

- Inhaling clouds of dust while working in soils or windy environments

Information and mapping

The Toxicology and Environmental Health Information Program (TEHIP)[79] is a comprehensive toxicology and environmental health web site, that includes open access to resources produced by US government agencies and organizations, and is maintained under the umbrella of the Specialized Information Service at the United States National Library of Medicine. TEHIP includes links to technical databases, bibliographies, tutorials, and consumer-oriented resources. TEHIP is responsible for the Toxicology Data Network (TOXNET),[80] an integrated system of toxicology and environmental health databases including the Hazardous Substances Data Bank, that are open access, i.e. available free of charge. TOXNET was retired in 2019.[81]

There are many environmental health mapping tools. TOXMAP is a geographic information system (GIS) from the Division of Specialized Information Services[82] of the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) that uses maps of the United States to help users visually explore data from the United States Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) Toxics Release Inventory and Superfund Basic Research Programs. TOXMAP is a resource funded by the US federal government. TOXMAP's chemical and environmental health information is taken from the NLM's Toxicology Data Network (TOXNET)[83] and PubMed, and from other authoritative sources.

Environmental health profession

Environmental health professionals may be known as environmental health officers, public health inspectors, environmental health specialists or environmental health practitioners. Researchers and policy-makers also play important roles in how environmental health is practiced in the field. In many European countries, physicians and veterinarians are involved in environmental health.[84] In the United Kingdom, practitioners must have a graduate degree in environmental health and be certified and registered with the Chartered Institute of Environmental Health or the Royal Environmental Health Institute of Scotland.[85] In Canada, practitioners in environmental health are required to obtain an approved bachelor's degree in environmental health along with the national professional certificate, the Certificate in Public Health Inspection (Canada), CPHI(C).[86] Many states in the United States also require that individuals have a bachelor's degree and professional licenses in order to practice environmental health.[87] California state law defines the scope of practice of environmental health as follows:[88]

- "Scope of practice in environmental health" means the practice of environmental health by registered environmental health specialists in the public and private sector within the meaning of this article and includes, but is not limited to, organization, management, education, enforcement, consultation, and emergency response for the purpose of prevention of environmental health hazards and the promotion and protection of the public health and the environment in the following areas: food protection; housing; institutional environmental health; land use; community noise control; recreational swimming areas and waters; electromagnetic radiation control; solid, liquid, and hazardous materials management; underground storage tank control; onsite septic systems; vector control; drinking water quality; water sanitation; emergency preparedness; and milk and dairy sanitation pursuant to Section 33113 of the Food and Agricultural Code.

The environmental health profession had its modern-day roots in the sanitary and public health movement of the United Kingdom. This was epitomized by Sir Edwin Chadwick, who was instrumental in the repeal of the poor laws, and in 1884 was the founding president of the Association of Public Sanitary Inspectors, now called the Chartered Institute of Environmental Health.[89]

See also

- EcoHealth

- Environmental disease

- Environmental medicine

- Environmental toxicology

- Epigenetics

- Exposure science

- Healing environments

- Health effects from noise

- Heavy metals

- Indoor air quality

- Industrial and organizational psychology

- NIEHS

- Nightingale's environmental theory

- One Health

- Pollution

- Volatile organic compound

Journals:

References

- ^ Dovjak, Mateja; Kukec, Andreja (2019), "Health Outcomes Related to Built Environments", Creating Healthy and Sustainable Buildings, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 43–82, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-19412-3_2, ISBN 978-3-030-19411-6, S2CID 190160283

- ^ Kelley T. The ecology of environmental health. Environ Health Insights. 2008 Jul 21;2:25-6. doi:10.1177/117863020800200001. PMID 21572828; PMCID: PMC3091335.

- ^ "Environmental Health - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2023-06-13.

- ^ "EHINZ". www.ehinz.ac.nz. Retrieved 2023-10-19.

- ^ academic.oup.com https://academic.oup.com/book/35585/chapter-abstract/306374236?redirectedFrom=fulltext#:~:text=Environmental%20health%20practice%20is%20concerned,can%20potentially%20affect%20human%20health. Retrieved 2023-10-19.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Novice, Robert, ed. (1999-03-29). "Overview of the environment and health in Europe in the 1990s" (PDF). World Health Organization.

- ^ WHO (n.d.). "Health topics: Environmental health". Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ Brooks Bryan, W, Gerding Justin, A, Landeen, E, et al. Environmental health practice challenges and research needs for U.S. Health Departments. Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127:125001.

- ^ MacArthur, I, Bonnefoy, X. Environmental health services in Europe 1. An overview of practice in the 1990s. WHO Reg Publ Eur Ser. 1997

- ^ "Experts See Growing Importance of Adding Environmental Health Content to Medical School Curricula". AAMC. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ^ Schwartz, Brian S.; Rischitelli, Gary; Hu, Howard (September 2005). "Editorial: The Future of Environmental Medicine in Environmental Health Perspectives: Where Should We Be Headed?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (9): A574–A576. doi:10.1289/ehp.113-1280414. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 1280414. PMID 16140601.

- ^ "environmental medicine — European Environment Agency". www.eea.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ^ Landrigan PL and Etzel RA. (2014). Textbook of Children's Environmental Health. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780199929573.

- ^ Jennings, Bruce (2016), H. Barrett, Drue; W. Ortmann, Leonard; Dawson, Angus; Saenz, Carla (eds.), "Environmental and Occupational Public Health", Public Health Ethics: Cases Spanning the Globe, Public Health Ethics Analysis, vol. 3, Cham (CH): Springer, pp. 177–202, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-23847-0_6, ISBN 978-3-319-23846-3, PMID 28590693, S2CID 168480156, retrieved 2023-06-13

- ^ Epidemiology, National Research Council (US) Committee on Environmental; Sciences, National Research Council (US) Commission on Life (1997). Environmental Epidemiology: The Context. National Academies Press (US).

- ^ National Research Council (US) Committee on Environmental Epidemiology (1991-01-01). Environmental Epidemiology, Volume 1. doi:10.17226/1802. ISBN 978-0-309-04496-7. PMID 25121252.

- ^ "Toxicology". National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ^ "Exposure Science". National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ^ "Environmental Engineers : Occupational Outlook Handbook: : U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics". www.bls.gov. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ^ "Environmental law". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ^ "INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL LAW AND BASIC PRINCIPLES OF ENVIRONMENTAL LAW – Folorunso and Co". 2021-02-05. Retrieved 2023-10-19.

- ^ Environmental Health: from Global to Local (2 Editor= Howard Frumkin ed.). San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons. 2010. ISBN 9780470567760.

- ^ World Resources Institute: August 2008 Monthly Update: Air Pollution's Causes, Consequences and Solutions Archived 2009-05-01 at the Wayback Machine Submitted by Matt Kallman on Wed, 2008-08-20 18:22. Retrieved on April 17, 2009

- ^ waterhealthconnection.org Overview of Waterborne Disease Trends Archived 2008-09-05 at the Wayback Machine By Patricia L. Meinhardt, MD, MPH, MA, Author. Retrieved on April 16, 2009

- ^ Pennsylvania State University – Potential Health Effects of Pesticides. Archived 2013-08-11 at the Wayback Machine by Eric S. Lorenz. 2007.

- ^ National and regional story (Netherlands) – Environmental burden of disease in Europe: the Abode project. EEA.

- ^ "Knows and unknowns on burden of disease due to chemicals: a systematic review". Press-Ustinov, A., et al. 2011. Environmental Health 10:9.

- ^ Schleicher, D. (1995). "Superfund’s Abandoned Hazardous Waste Sites". In A. Wildavsky (Ed.), But Is it True?: A Citizen’s Guide to Environmental Health and Safety Issues (153–184) . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [ISBN missing]

- ^ Richard Fuller, Philip J Landrigan, Kalpana Balakrishnan, Glynda Bathan, Stephan Bose-O'Reilly, Michael Brauer, Jack Caravanos, Tom Chiles, Aaron Cohen, Lilian Corra, Maureen Cropper, Greg Ferraro, Jill Hanna, David Hanrahan, Howard Hu, David Hunter, Gloria Janata, Rachael Kupka, Bruce Lanphear, Maureen Lichtveld, Keith Martin, Adetoun Mustapha, Ernesto Sanchez-Triana, Karti Sandilya, Laura Schaefli, Joseph Shaw, Jessica Seddon, William Suk, Martha María Téllez-Rojo, Chonghuai Yan, Pollution and health: a progress update, The Lancet Planetary Health, Volume 6, Issue 6, 2022, Pages e535-e547, ISSN 2542-5196, doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00090-0

- ^ "Air pollution". www.who.int. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ "7 million premature deaths annually linked to air pollution". www.who.int. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ Rovira J, Domingo JL, Schuhmacher M. Air quality, health impacts and burden of disease due to air pollution (PM10, PM2.5, NO2 and O3): Application of AirQ+ model to the Camp de Tarragona County (Catalonia, Spain). Sci Total Environ. 2020 Feb 10;703:135538. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135538. Epub 2019 Nov 18. PMID 31759725.

- ^ Prüss-Ustün, A., J. Wolf, C. Corvalán, R. Bos, and M. Neira. "Preventing disease through healthy environments: A global assessment of the burden of disease from environmental risks. 2016." World Health Organization. https://apps. who. int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/204585/9789241565196_eng. pdf (2020)

- ^ US EPA, OAR (2015-09-10). "Overview of Air Pollution from Transportation". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ "Air Pollution and Your Health". National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ Abdo, Nour, Khader, Yousef S., Abdelrahman, Mostafa, Graboski-Bauer, Ashley, Malkawi, Mazen, Al-Sharif, Munjed and Elbetieha, Ahmad M.. "Respiratory health outcomes and air pollution in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: a systematic review" Reviews on Environmental Health 31, no. 2 (2016): 259-280. doi:10.1515/reveh-2015-0076

- ^ a b Vallero, Daniel., and Daniel. Vallero. Fundamentals of Air Pollution. 5th ed. San Diego: Elsevier Science & Technology, 2014.

- ^ Manisalidis, Ioannis; Stavropoulou, Elisavet; Stavropoulos, Agathangelos; Bezirtzoglou, Eugenia (2020). "Environmental and Health Impacts of Air Pollution: A Review". Frontiers in Public Health. 8. ISSN 2296-2565.

- ^ a b c “Cleaner Indoor air.(Public Health Round-up)(World Health Organization’s Guidelines to Improve Indoor Air quality)(Brief Article).” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 92, no. 12 (2014): 852-853.

- ^ Cincinelli, Alessandra, and Tania Martellini. “Indoor Air Quality and Health.” International journal of environmental research and public health 14, no. 11 (2017): 1286–1291.

- ^ Lanthier-Veilleux M, Baron G, Généreux M. Respiratory Diseases in University Students Associated with Exposure to Residential Dampness or Mold. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016 Nov 18;13(11):1154. doi:10.3390/ijerph13111154. PMID 27869727; PMCID: PMC5129364.

- ^ Mueller D, Uibel S, Braun M, Klingelhoefer D, Takemura M, Groneberg DA. Tobacco smoke particles and indoor air quality (ToPIQ) - the protocol of a new study. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2011 Dec 21;6:35. doi:10.1186/1745-6673-6-35. PMID 22188808; PMCID: PMC3260229.

- ^ Hoffmann, D., and I. Hoffmann. "Chapter 5; The Changing Cigarette: Chemical Studies and Bioassays." Risks Associated with Smoking Cigarettes with Low Machine-Measured Yields of Tar and Nicotine-Monograph 13: 160-170.

- ^ Vidale, Simone, A. Bonanomi, M. Guidotti, M. Arnaboldi, and R. Sterzi. "Air pollution positively correlates with daily stroke admission and in hospital mortality: a study in the urban area of Como, Italy." Neurological sciences 31 (2010): 179-182.

- ^ Paton-Walsh, Clare, Peter Rayner, Jack Simmons, Sonya L. Fiddes, Robyn Schofield, Howard Bridgman, Stephanie Beaupark, Richard Broome, Scott D. Chambers, Lisa Tzu-Chi Chang, Martin Cope, Christine T. Cowie, Maximilien Desservettaz, Doreena Dominick, Kathryn Emmerson, Hugh Forehead, Ian E. Galbally, Alan Griffiths, Élise-Andrée Guérette, Alison Haynes, Jane Heyworth, Bin Jalaludin, Ruby Kan, Melita Keywood, Khalia Monk, Geoffrey G. Morgan, Hiep Nguyen Duc, Frances Phillips, Robert Popek, Yvonne Scorgie, Jeremy D. Silver, Steve Utembe, Imogen Wadlow, Stephen R. Wilson, and Yang Zhang. 2019. "A Clean Air Plan for Sydney: An Overview of the Special Issue on Air Quality in New South Wales" Atmosphere 10, no. 12: 774. doi:10.3390/atmos10120774

- ^ Melita Keywood, Martin Cope, C.P. Mick Meyer, Yoshi Iinuma, Kathryn Emmerson, When smoke comes to town: The impact of biomass burning smoke on air quality, Atmospheric Environment, Volume 121, 2015, Pages 13-21, ISSN 1352-2310, doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.03.050

- ^ Romanello M, McGushin A, Di Napoli C, Drummond P, Hughes N, Jamart L, Kennard H, Lampard P, Solano Rodriguez B, Arnell N, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Belesova K, Cai W, Campbell-Lendrum D, Capstick S, Chambers J, Chu L, Ciampi L, Dalin C, Dasandi N, Dasgupta S, Davies M, Dominguez-Salas P, Dubrow R, Ebi KL, Eckelman M, Ekins P, Escobar LE, Georgeson L, Grace D, Graham H, Gunther SH, Hartinger S, He K, Heaviside C, Hess J, Hsu SC, Jankin S, Jimenez MP, Kelman I, Kiesewetter G, Kinney PL, Kjellstrom T, Kniveton D, Lee JKW, Lemke B, Liu Y, Liu Z, Lott M, Lowe R, Martinez-Urtaza J, Maslin M, McAllister L, McMichael C, Mi Z, Milner J, Minor K, Mohajeri N, Moradi-Lakeh M, Morrissey K, Munzert S, Murray KA, Neville T, Nilsson M, Obradovich N, Sewe MO, Oreszczyn T, Otto M, Owfi F, Pearman O, Pencheon D, Rabbaniha M, Robinson E, Rocklöv J, Salas RN, Semenza JC, Sherman J, Shi L, Springmann M, Tabatabaei M, Taylor J, Trinanes J, Shumake-Guillemot J, Vu B, Wagner F, Wilkinson P, Winning M, Yglesias M, Zhang S, Gong P, Montgomery H, Costello A, Hamilton I. The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future. Lancet. 2021 Oct 30;398(10311):1619-1662. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01787-6. Epub 2021 Oct 20. Erratum in: Lancet. 2021 Dec 11;398(10317):2148. PMID 34687662.

- ^ a b Li A, Toll M, Martino E, Wiesel I, Botha F, Bentley R. Vulnerability and recovery: Long-term mental and physical health trajectories following climate-related disasters. Soc Sci Med. 2023 Mar;320:115681. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115681. Epub 2023 Jan 20. PMID 36731303.

- ^ a b "Climate Impacts on Human Health | Climate Change Impacts | US EPA". climatechange.chicago.gov. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ^ USGCRP (2016). Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment. Crimmins, A., J. Balbus, J.L. Gamble, C.B. Beard, J.E. Bell, D. Dodgen, R.J. Eisen, N.Fann, M.D. Hawkins, S.C. Herring, L. Jantarasami, D.M. Mills, S. Saha, M.C. Sarofim, J.Trtanj, and L.Ziska, Eds. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC. 312 pp. dx.doi.org/10.7930/J0R49NQX.

- ^ a b c "Creating the Healthiest Nation: Water and Health Equity". American Public Health Association.

- ^ Kaufman, Joel D., and Anjum Hajat. "Confronting environmental racism." Environmental Health Perspectives 129, no. 5 (2021): 051001.

- ^ a b c Tessum, Christopher W., David A. Paolella, Sarah E. Chambliss, Joshua S. Apte, Jason D. Hill, and Julian D. Marshall. “PM2.5 Polluters Disproportionately and Systemically Affect People of Color in the United States.” Science advances 7, no. 18 (2021).

- ^ a b Adua, Lazarus. “Super Polluters and Carbon Emissions: Spotlighting How Higher-Income and Wealthier Households Disproportionately Despoil Our Atmospheric Commons.” Energy policy 162 (2022): 7–10.

- ^ Jariwala, Hiral J., Huma S. Syed, Minarva J. Pandya, and Yogesh M. Gajera. "Noise pollution & human health: a review." Indoor Built Environ 1, no. 1 (2017): 1-4.

- ^ Basner, M., Babisch, W., Davis, A., Brink, M., Clark, C., THE LANCET, Volume 383, issue 9925(April, 2014), page 1325-1332.

- ^ a b c d "The Effects of Noise on Health". hms.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ^ Foraster, M., Esnaola, M., López-Vicente, M., Rivas, I., Álvarez-Pedrerol, M., Persavento, C., Sebastian-Galles, N., Pujol, J., Dadvand, P., & Sunyer, J. (2022). Exposure to road traffic noise and cognitive development in schoolchildren in Barcelona, Spain: A population-based cohort study. PLOS Medicine, 19(6), e1004001. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1004001

- ^ Basner, M., Clark, C., & Hansell, A. (2017). Aviation noise impacts: State of the science. Noise and Health, 19(87), 41–50. doi:10.4103/nah.NAH_104_16

- ^ Passchier, W., Passchier, W., Noise Exposure and Public Health, Environmental Health perspective, Vol. 108, Supplemental (March, 2000).

- ^ Hammersen F, Niemann H, Hoebel J. Environmental Noise Annoyance and Mental Health in Adults: Findings from the Cross-Sectional German Health Update (GEDA) Study 2012. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016 Sep 26;13(10):954. doi:10.3390/ijerph13100954. PMID 27681736; PMCID: PMC5086693.

- ^ a b c Mathias Basner, Wolfgang Babisch, Adrian Davis, Mark Brink, Charlotte Clark, Sabine Janssen, Stephen Stansfeld, Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health, The Lancet, Volume 383, Issue 9925, 2014, Pages 1325-1332, ISSN 0140-6736, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61613-X

- ^ Basner, Mathias, Wolfgang Babisch, Adrian Davis, Mark Brink, Charlotte Clark, Sabine Janssen, and Stephen Stansfeld. "Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health." The lancet 383, no. 9925 (2014): 1325-1332.

- ^ "Daytime Somnolence - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Martin. "Water and Sanitation". United Nations Sustainable Development. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ "— SDG Indicators". unstats.un.org. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Report on the environment: drinking water. Available at: https://cfpub.epa.gov. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Drinking-water". www.who.int. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ^ Omole, David O., and Julius M. Ndambuki. 2014. "Sustainable Living in Africa: Case of Water, Sanitation, Air Pollution and Energy" Sustainability 6, no. 8: 5187-5202. doi:10.3390/su6085187

- ^ Emenike, C.P., I.T. Tenebe, D.O. Omole, B.U. Ngene, B.I. Oniemayin, O. Maxwell, and B.I. Onoka. “Accessing Safe Drinking Water in Sub-Saharan Africa: Issues and Challenges in South–West Nigeria.” Sustainable cities and society 30 (2017): 263–272.

- ^ Environmental Protection Agency. (2019, March 15). Lead in Drinking Water in Schools and Childcare Facilities. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/dwreginfo/lead-drinking-waterschools-and-childcare-facilities

- ^ a b Switzer, David, and Manuel P Teodoro. “The Color of Drinking Water: Class, Race, Ethnicity, and Safe Drinking Water Act Compliance.” Journal of the American Water Works Association. 109, no. 9 (2017): 40–45.

- ^ Patel, A. I., & Schmidt, L. A. (2017). Water Access in the United States: Health Disparities Abound and Solutions Are Urgently Needed. American Journal of Public Health, 107(9), 13541356. doi:10.2105/ajph.2017.303972

- ^ Thomas T. Shen, Air pollution assessment of toxic emissions from hazardous waste lagoons and landfills, Environment International, Volume 11, Issue 1, 1985, Pages 71-76, ISSN 0160-4120, doi:10.1016/0160-4120(85)90104-7

- ^ Glatter-Götz, Helene, Paul Mohai, Willi Haas, and Christoph Plutzar. “Environmental Inequality in Austria: Do Inhabitants’ Socioeconomic Characteristics Differ Depending on Their Proximity to Industrial Polluters?” Environmental research letters 14, no. 7 (2019): 1–11.

- ^ US EPA, OLEM (2015-11-25). "Learn the Basics of Hazardous Waste". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ Hapke, H.-J. (1996). "Heavy metal transfer in the food chain to humans". Fertilizers and Environment. pp. 431–436. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-1586-2_73. ISBN 978-94-010-7210-6.

- ^ a b Rodríguez Eugenio, Natalia (2021). "Environmental, health and socio-economic impacts of soil pollution". Global assessment of soil pollution: Report. doi:10.4060/cb4894en. ISBN 978-92-5-134469-9.

- ^ "TEHIP". United States National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "TOXNET". United States National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2019-06-11. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ^ "TOXNET Update: New Locations for TOXNET Content". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

- ^ sis.nlm.nih.gov

- ^ "toxnet.nlm.nih.gov". Archived from the original on 2019-06-11. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ^ Ferri, Maurizio; Lloyd-Evans, Meredith (2021-02-27). "The contribution of veterinary public health to the management of the COVID-19 pandemic from a One Health perspective". One Health. 12: 100230. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100230. ISSN 2352-7714. PMC 7912361. PMID 33681446.

- ^ "Job Profiles: Environmental health officer". National Careers Service (UK). Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ^ "Canadian Institute of Public Health Inspectors". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ States, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Assess Training Needs for Occupational Safety and Health Personnel in the United (2000), "Occupational Safety and Health Professionals", Safe Work in the 21st Century: Education and Training Needs for the Next Decade's Occupational Safety and Health Personnel, National Academies Press (US), retrieved 2023-10-19

- ^ California Health and Safety Code, section 106615(e)

- ^ "History of CIEH". CIEH. Retrieved 2023-10-19.

Further reading

- Andrew M. Pope; David P. Rall (1995). Committee on Curriculum Development in Environmental Medicine at the Institute of Medicine (ed.). Environmental Medicine – Integrating a Missing Element into Medical Education. National Academies Press. ISBN 0309051401.

- Lifestyle factors that can induce an independent and persistent low-grade systemic inflammatory response: a wholistic approach George Vrousgos, N.D. – Southern Cross University

- Kate Davies (2013). The Rise of the U.S. Environmental Health Movement. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442221376.

- White, Franklin; Stallones, Lorann; Last, John M. (2013). Global Public Health: Ecological Foundations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-975190-7.

- Jouko Tuomisto (2005). "Arsenic to zoonoses – One hundred questions about the environment and health". Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos (National Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland). Archived from the original on 2015-01-15. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "Environment and Health A to Z" (PDF). NIEHS. 2023.