State of socialist orientation

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism–Leninism |

|---|

|

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

In the political terminology of the former Soviet Union, the socialist-leaning countries (Template:Lang-ru) were the post-colonial Third World countries which the Soviet Union recognized as adhering to the ideas of socialism in the Marxist–Leninist understanding. As a result, these countries received significant economic and military support.[1] In Soviet press, these states were also called "countries on the path of the construction of socialism" (Template:Lang-ru) and "countries on the path of the socialist development" (Template:Lang-ru). All these terms meant to draw a distinction from the true socialist states (in Marxist–Leninist understanding).[2]

The use of the term was partly a result of a reassessment of national liberation movements in the Third World following World War II, widespread decolonization and the emergence of the Non-Aligned Movement as well as Nikita Khrushchev's Secret Speech to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the de-Stalinization of Soviet Marxism.[3] The discussion of anti-colonial struggle at the 2nd World Congress of the Comintern in 1920 had been formulated in terms of a debate between those for an alliance with the anti-imperialist national bourgeoisie (initially advocated by Vladimir Lenin) and those for a pure class line of socialist, anti-feudal as well as anti-imperialist struggle (such as M. N. Roy).[4] The revolutions of the post-war decolonization era (excepting those led by explicitly proletarian forces such as the Vietnamese Revolution), e.g. the rise of Nasserism, were initially seen by many communists as a new form of bourgeois nationalism and there were often sharp conflicts between communists and nationalists.[5] However, the adoption of leftist economic programs (such as nationalization and/or land reform) by many of these movements and governments as well as the international alliances between the revolutionary nationalists and the Soviet Union obliged communists to reassess their nature. These movements were now seen as neither classical bourgeois nationalists nor socialist per se, but rather offering the possibility of "non-capitalist development" as a path of "transition to socialism".[6] At various times, these states included Algeria, Angola, Central African Republic, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Libya, Mozambique, South Yemen and many others.[1][2]

In Soviet political science, "socialist orientation" was defined to be an initial period of the development in countries which rejected capitalism, but did not yet have the prerequisites for the socialist revolution or development. Along these lines, a more cautious synonym was used, namely "countries on the path of non-capitalist development". A 1986 Soviet reference book on Africa claimed that about one third of African states followed this path.[2]

In some countries designated as socialist-leaning by the Soviet Union such as India, this formulation was sharply criticized by emerging Maoist or Chinese-leaning groups such as the Communist Party of India (Marxist), who considered the doctrine class collaborationist as part of the larger Sino-Soviet split and the Maoist struggle against so-called Soviet revisionism.

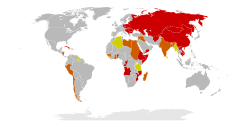

List of socialist-leaning states

Some of these countries had communist governments while others (italicized) did not.

Egypt (1954–1973)

Egypt (1954–1973) Syria (1955–1991)

Syria (1955–1991) Iraq (1958–1963, 1968–1991)

Iraq (1958–1963, 1968–1991) Guinea (1960–1978)

Guinea (1960–1978) Mali (1960–1968)

Mali (1960–1968) Somali Democratic Republic (1969–1977)[a]

Somali Democratic Republic (1969–1977)[a] Burma (1962–1988)

Burma (1962–1988) Algeria (1962–1990)

Algeria (1962–1990) Ghana (1964–1966)

Ghana (1964–1966) Peru (1968–1975)

Peru (1968–1975) Sudan (1969–1971)

Sudan (1969–1971) Equatorial Guinea (1968–1979)

Equatorial Guinea (1968–1979) Libya (1969–1991)

Libya (1969–1991) People's Republic of the Congo (1969–1991)

People's Republic of the Congo (1969–1991) Chile (1970–1973)

Chile (1970–1973) Cape Verde (1975–1991)

Cape Verde (1975–1991) Sao Tome and Principe (1975–1991)

Sao Tome and Principe (1975–1991) South Yemen (1967–1990)

South Yemen (1967–1990) Uganda (1972–1979)

Uganda (1972–1979) Indonesia (1960–1965)

Indonesia (1960–1965) India (1955–1989)

India (1955–1989) People's Republic of Bangladesh (1971–1975)

People's Republic of Bangladesh (1971–1975) Democratic Republic of Madagascar (1972–1991)

Democratic Republic of Madagascar (1972–1991) Guinea Bissau (1973–1991)

Guinea Bissau (1973–1991) Derg (1974–1987)

Derg (1974–1987) People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (1987–1991)

People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (1987–1991) Lao People's Democratic Republic (1975–1991)

Lao People's Democratic Republic (1975–1991) People's Republic of Benin (1975–1990)

People's Republic of Benin (1975–1990) People's Republic of Mozambique (1975–1990)

People's Republic of Mozambique (1975–1990) People's Republic of Angola (1975–1991)

People's Republic of Angola (1975–1991) Seychelles (1977–1991)

Seychelles (1977–1991) Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (1978–1991)

Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (1978–1991) People's Revolutionary Government of Grenada (1979–1983)

People's Revolutionary Government of Grenada (1979–1983) Nicaragua (1979–1990)

Nicaragua (1979–1990) People's Republic of Kampuchea (1979–1989)

People's Republic of Kampuchea (1979–1989) Burkina Faso (1983–1987)

Burkina Faso (1983–1987)

See also

- African socialism

- Arab socialism

- Bureaucratic collectivism

- Communist state

- Congress of the Peoples of the East

- Deformed workers' state

- Degenerated workers' state

- Developmentalism

- List of socialist states

- Marxism–Leninism

- New class

- Nomenklatura

- People's republic

- Politics of the Soviet Union

- Socialist state

- Soviet Bloc

- Soviet Empire

- State capitalism

- State socialism

Notes

- ^ At the outbreak of the Somali invasion of Ethiopia in 1977, the Soviet Union ceased to support Somalia, with the corresponding change in rhetoric. In turn, Somalia broke diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and the United States adopted Somalia as a Cold War ally.[7]

References

- ^ a b Trenin, Dmitri (2011). Post-Imperium: A Eurasian Story. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. p. 144.

- ^ a b c "Sotsialisticheskaya oriyentatsiya" (in Russian). An article from the 1986–1987 Soviet reference book Afrika. Entsiklopedicheskiy spravochnik.

- ^ Tareq, Ismael (2005). The Communist Movement in the Arab World. London: Rutledge. Print. pp. 24–25.

- ^ Lenin, Vladimir (1965) [19 July–7 August 1920). "Report of the Commission on the National and the Colonial Question". Collected Works. 31. Moscow: Progress Publishers. pp. 213–263.

- ^ Tareq, Ismael (2005). The Communist Movement in the Arab World. London: Rutledge. Print. p. 21.

- ^ Tareq, Ismael (2005). The Communist Movement in the Arab World. London: Rutledge. Print. p. 24.

- ^ Crockatt, Richard (1995). The Fifty Years War: The United States and the Soviet Union in World Politics. London and New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10471-5.