Bicycling and feminism

The bicycle had a significant impact on the lives of women in a majority of topics.[1][2][3] The greatest impact the bicycle had on the role of women occurred in the 1890s during the bicycle craze that swept American and European society.[4] During this time, the primary achievement the bicycle gained for the women's movement is that it gave women a greater amount of social mobility.[3][5] The feminist Annie Londonderry accomplished her around-the-globe bicycle trip as the first woman in this time.[6][7][8] Due to the expense and various payment plans offered by American bicycle companies, the bicycle was affordable to everyone in society.[3] However, the bicycle impacted upper and middle class white women the most.[3] This transformed their role in society from remaining in the private or domestic sphere as caregivers, wives, and mothers to one of greater public appearance and involvement in the community.[3][9]

Bikes in Space is a series of sci-fi books themed around bicycling and feminism.[10]

Pre–bicycle craze cycling

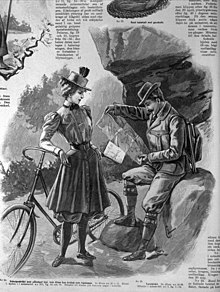

Before the 1890s, the bicycle was a vastly different vehicle and was by no means popular. Between the 1860s and the mid-1880s, the standard bicycle was the ordinary or high wheeler, which was both hard to master and dangerous to use. While the ordinary was exclusively used by men, women were allowed to use bicycles such as the two-seater sociable, the tandem, and the tricycle. Beginning in the late 1860s companionate riding became a popular social activity for men and women. These vehicles allowed men and women to develop new methods of coed socialization. However, up until the mid 1880s, women were primarily dependent upon men in order to participate in cycling. The presence of a man in control of the sociable assumed that the man could keep the woman safe from the dangers of riding a bike alone, thereby assuming the authority of man. So while companionate riding was revolutionary in the development in sociability between men and women, it kept women in an inferior position to men by assuming that the man had the power over the bicycle in that situation.[3][11]

Clothing

Between 1885 and 1895, inventors and engineers vastly improved the previous generation of bicycle to what was then called safety bicycle.[3] With these developments, a type of safety bicycle was designed for women in particular with a drop frame in order to accommodate women’s clothes. However, the long skirts and the tight-fitted bodices of this time period made cycling an even greater challenge. Therefore, several modified outfits were offered to women that would accommodate the bicycle. Some modifications included divided skirts, skirts that shortened with drawstrings, skirts that converted to bloomers, skirt-securing devices that kept the fabric close to the ankle, and a bicycle corset consisting of a sturdy, straight under-bodice with extra back support and a looser fit. Of all the bicycle costumes, the bloomer costume was and still is the most widely known from this time period. This consisted of full trousers, gathered at the ankle, worn with a calf-length skirt with a fashionable jacket on top.[11]

These clothes were met with mixed approval. Elizabeth Cady Stanton in her notes on whether or not women should ride a bicycle stated, "To sum up, I would say, let women ride .... If some prefer the [bulk] skirts flying in the wind exhausted in the wheels let them run the risk of their folly; If others prefer bloomers let them enjoy their choice- if others prefer knickerbockers, leave them in peace."[2] In instructive books written for women on how to ride a bicycle, many authors insist that wearing bicycle costumes made it easier to ride.[12] In both cases, it seems that the decision to wear these athletic costumes was a personal choice for women. By making this choice, women to a small degree were able to take control of their life. At the same time, it was presented as a rational choice as wearing the full fashion of the time could make cycling more difficult for the rider. Because of this the decision to wear these clothes was closely related to the decision to ride a bicycle.[11]

For the most part, men were the main opponents of women wearing bicycle clothing and in particular, bloomers. This can be seen in a lot of songs from this time period. For example, a rendition of “Mary Had a Little Lamb” from 1895 written by Stanislaus Stange had a verse that went:

“Dear Mary,” said the little lamb,“It gives me quite a fright To see the girls on bicycles, They’re such a novel sight.Why is it they all Bloomers wear?The sight my blood congeals.”Then Mary touched her forehead thus, And gently murmured: “Wheels.”[13]

In this case, the very idea of the bicycle suit and women's potential to wear it disturbed some men. They saw these suits and in particular bloomers as ugly or shameful. In particular, they saw these bicycle costumes as a physical representation of women stealing men’s characteristics, thereby blurring the lines between femininity and masculinity and what is socially acceptable for each group. What this fear reveals is a realistic notion that women were taking on a greater role of independence of which had previously been characterized as masculine.[3][11]

19th-century medicine

During the late nineteenth century, doctors began encouraging everyone in public to exercise more often and cycling became a popular activity in which to do so. However, doctors were worried about the effects of excessive cycling, particularly how it affected women. An 1895 article in “The Literary Digest” reviewed literature from the time period, which discussed the bicycle face, and noted that The Springfield Republican warned against excessive cycling by “women, girls, and middle-aged men.”[14] The bicycle face was described as a face usually flushed, but sometimes pale, often with lips ore or less drawn, and the beginning of dark shadows under the eyes, and always an expression of weariness.[14] These articles pushed forth the belief that excessive cycling made women vulnerable to many diseases such as developing an exophthalmic goiter, appendicitis, and internal inflammation.[15] His article was subsequently discussed and analyzed in The Advertiser.[16] Overall, these diagnoses reflect on how doctors during this time period viewed women and their bodies as weak.

Another concern doctors had about women riding the bicycle was over their sexual health. Doctors believed that the bicycle saddle taught masturbation to women and girls. Riding astride anything was seen as too masculine for any proper woman. These physicians wrote in detail in medical journals about how the bicycle could be used for masturbation:

The saddle can be tilted in every bicycle as desired… In this way a girl… could, by carrying the front peak or pommel high, or by relaxing the stretched leather in order to let it form a deep, hammock-like concavity which would fit itself snugly over the entire vulva and reach up in front, bring about constant friction over the clitoris and labia. This pressure would be much increased by stooping forward and the warmth generated from vigorous exercise might further increase feeling.[5][failed verification]

These doctors were not concerned with sexual health, but rather sexual morality. Young women were supposed to be chaste and pure. They were trained from a young age to guard their sexual innocence. The fact that the bicycle had potential to awaken sexual feelings in women not only threatened their sexual purity, but also threatened to destroy gender definitions of sexual morality. Therefore, the bicycle is seen again as blurring the definition of masculine and feminine characteristics.[5]

At the same time as male doctors were stating the capabilities of women and the weakness of their bodies in relation to the bicycle, women began to express what their bodies were capable of through magazine articles. Women like Mary Bisland, Mary Sargent Hopkins, and Emma Moffett Tyng contested medical commonplaces and promoted new ones in their place. These women stated that cycling brought long-inactive muscles back to life, and helped riders feel better emotionally and encouraged women to use their own experiences with the bicycle to determine their physical limits. These women brought to public attention the positive aspects that help women riders. The bicycle not only makes them literally stronger, but also makes them more confident in their own abilities. This in turn not only gives women a greater agency over their body, but also mentally strengthens them to take on their previous domestic role and explore new roles in the public sphere.[17]

Bicycle enthusiasts disagreed with this medical assessment, and asserted that the physical activity was good to improve one's health and vitality.[18]

Solo female bicycle travelers

Bicycle touring is a type of adventure travel, whereby a traveler uses a bicycle as the major means of transportation. A bicycle traveler might also use panniers to transport her equipment. Such travel can be almost completely self-sustained and autonomous, once the equipment includes a tent, cooking tools, a medical pack, repair tools, cooking fuel, water containers and multiple days of food supplies. Women Cycle the World is one of the many websites, which offer a list solo female long-distance cyclists and their blog.[19] For instance, Rebecca Lowe crossed Iran, Dervla Murphy crossed Afganistan and Helen Lloyd crossed Africa.[20][21] The book WOW — Women on Wheels by solo female cycle traveler Loretta Henderson reported a global number of 245 solo female cycle travelers.[22] Annie Londonderry is the first woman to have cycled the world as early as in 1894–95.[8]

Issues of safety and security for solo female long-distance cyclists are often raised by those meeting them for the first time.[23][24] Such sources often come off with encouraging answers and useful advices, such as researching road and destination, staying visible on the road, and planning lodging options such as camping, bed and breakfast and Warm Showers ahead.[25][26][27]

Publications

During the 1890s, many women and some men wrote self-help books in order to help women learn how to ride a bicycle. Within these books, they gave tips and personal reflections about the impact of the bicycle on their lives. Frances Elizabeth Willard, the national president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) wrote a book called “A Wheel Within A Wheel”, in which she discusses the exhilaration and health benefits she received by learning to ride as well as how she used cycling as a compelling social activity to stop men and women from drinking.[1]

Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote that the bicycle was a tool which motivated women to gain strength and take on increased roles in society.[28] Susan B. Anthony stated in 1896: "Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel."[28]

Beatrice Grimshaw, who went on to a life of travel and adventure, describes a girlhood of Victorian propriety, in which she was: "the Revolting Daughter–as they called them then. I bought a bicycle, with difficulty. I rode it unchaperoned, mile and miles beyond the limits possible to the soberly trotting horses. The world opened before me. And as soon as my twenty-first birthday dawned, I went away from home, to see what the world might to give to daughters who revolted."[29]

Within the experiences of all these women, they indicate a similar experience of the world opening up to them. In the literal sense, they could leave the private sphere for the public sphere and in doing so escape the cult of domesticity in which societal norms kept them imprisoned. At the same time, they see the potential for new opportunities in which women can take an active role within their community. Through these readings, the women begin to see their potential as active and independent members of society.[30][12][1]

See also

- Islamic bicycle

- History of the bicycle

- Timeline of women's legal rights (other than voting)

- Victorian dress reform

References

- ^ a b c Willard, Frances Elizabeth (1895). A Wheel Within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle with Some Reflection By the Way. Fleming H. Revell Company. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. "Elizabeth Cady Stanton Papers: Speeches and Writings- 1902 Articles; Undated; "Shall Women Ride the Bicycle?" undated". Library of Congress. Library of Congress. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harmond, Richard (1971). "Progress and Flight: An Interpretation of the American Cycle Craze of the 1890s". Journal of Social History. 5 (2): 235–257. doi:10.1353/jsh/5.2.235. JSTOR 3786413.

- ^ Rubinstein, David (1977). "Cycling in the 1890s". Victorian Studies. 21 (1): 47–71. JSTOR 3825934.

- ^ a b c Hallenbeck, Sarah (2010). "Riding Out of Bounds: Women Bicyclists' Embodied Medical Authority". Rhetoric Review. 29 (4): 327–345. doi:10.1080/07350198.2010.510054. JSTOR 40997180.

- ^ Blickenstaff, Brian (23 September 2016). "Annie Londonderry: the Self-Promoting Feminist Who Biked Around the World". Vice. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "10 Things you Didn't Know about Annie Londonderry". Total Women's Cycling. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ a b "First woman to cycle the globe begins journey". Jewish Women's Archive. 25 June 1894. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Petty, Ross D. (2010). "Bicycling in Minneapolis in the Early 20th Century". Minnesota History. 62 (3): 66–101. JSTOR 25769527.

- ^ "Bikes in Space | Taking the Lane". takingthelane.com. Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- ^ a b c d Christie-Robin, J.; Ozada, B. T.; Lòpex-Gydosh, D. (2012). "From Bustles to Bloomers: Exploring the Bicycle's Influence on American Women's Fashion, 1880-1914". The Journal of American Culture. 35 (4). ProQuest 1285120225.

- ^ a b Brown, Herbert E. (1895). Betsey Jane on Wheels: A Tale of the Bicycle Craze. W. B. Conkey.

- ^ Edwards, Julian. "Songs and Selections from Madeleine, or The Magic Kiss". Levy Music Collection. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ a b "The 'Bicycle Face'". The Literary Digest. 11 (19): 8 (548). 7 September 1895.

- ^ Shadwell, A. (1 February 1897). "The hidden dangers of cycling". National Review.

- ^ "The Intoxicating Bicycle". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 16 March 1897. p. 6.

- ^ Garvey, Ellen Gruber (1995). "Reframing the Bicycle: Advertising-Supported Magazines and Scorching Women". American Quarterly. 47 (1): 66–101. doi:10.2307/2713325. JSTOR 2713325.

- ^ Herlihy, David V. (2006). Bicycle: The History. Yale University Press. pp. 270–273. ISBN 978-0300120479.

- ^ "About". Women Cycle The World. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ "Is it foolish for a woman to cycle alone across the Middle East?". BBC News. 1 April 2017. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Lloyd, Helen (2013). Desert snow : one girl's take on Africa by bike. ISBN 9780957660601.

- ^ Rosemary (14 October 2016). "WOW - Women on Wheels - a book for women cyclists". Women Travel The World.

- ^ Buhring, Juliana. "Is It Safe For Women To Go Bicycle Touring Alone?". bicycletouringpro.com. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ "Is It Safe For Women To Go Bicycle Touring Alone?". bicycletouringpro.com. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Lesley Reader; Lesley Ridout (2015). The Rough Guide to First-Time Asia. The Rough Guide.

- ^ Sheelagh (2019). "7 Tips for a Safe Solo Bike Tour". sheelaghdaly.com.

- ^ Anna Kitlar (2017). "Anna Kitlar ~ Bikexploring ~ Bikepacking". bicycletravellingwomen.com.

- ^ a b Vivanco, Luis Antonio (2013). Reconsidering the Bicycle: An Anthropological Perspective on a New (old) Thing. Routledge. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-0415503884.

- ^ Grimshaw, Beatrice (April 1939). "How I found adventure". Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ^ Ward, Maria E. (1896). Bicycling For Ladies. Brentano's.

Further reading

- Macy, Sue (2011). Wheels of Change: How Women Rode the Bicycle to Freedom (With a Few Flat Tires Along the Way). National Geographic. ISBN 978-1426307614.

- Shadwell, A. (1 February 1897). "The hidden dangers of cycling". National Review.