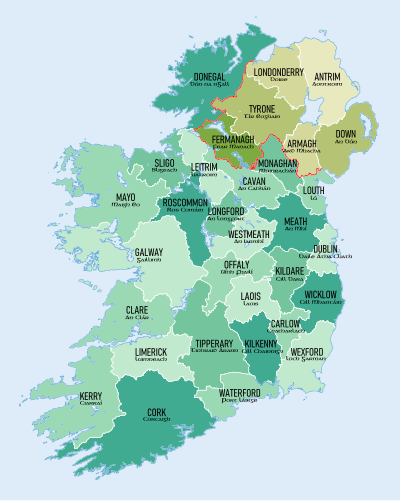

Counties of Ireland

The counties of Ireland (Irish: contaetha na hÉireann; Ulster-Scots: coonties o Airlann) are sub-national divisions that have been, and in some cases continue to be, used to geographically demarcate areas of local government. These land divisions were formed following the Norman invasion of Ireland in imitation of the counties then in use as units of local government in the Kingdom of England.[1] The older term ‘shire’ was historically equivalent to ‘county’. The principal function of the county was to impose royal control in the areas of taxation, security and the administration of justice at the local level. Cambro-Norman control was initially limited to the southeastern parts of Ireland; a further four centuries elapsed before the entire island was shired. At the same time, the now obsolete concept of county corporate elevated a small number of towns and cities to a status which was deemed to be no less important than the existing counties in which they lay. This double control mechanism of 32 counties plus 10 counties corporate remained unchanged for a little over two centuries until the early 19th century. Since then, counties have been adapted and in some cases divided by legislation to meet new administrative and political requirements.

The powers exercised by the Cambro-Norman barons and the Old English nobility waned over time. New offices of political control came to be established at a county level. In the Republic of Ireland, some counties have been split resulting in the creation of new counties. Along with certain defined cities, counties still form the basis for the demarcation of areas of local government in the Republic of Ireland. Currently, there are 26 county level, 3 city level and 2 city and county entities – the modern equivalent of counties corporate – that are used to demarcate areas of local government in the Republic.

In Northern Ireland, counties are no longer used for local government; districts are instead used. Upon the partition of Ireland in 1921, the county became one of the basic land divisions employed, along with county boroughs.

Terminology

The word "county" has come to be used in different senses for different purposes. In common usage, many people have in mind the 32 counties that existed prior to 1838 – the so-called traditional counties. However, in official usage in the Republic of Ireland, the term often refers to the 28 modern counties. The term is also conflated with the 31 areas currently used to demarcate areas of local government in the Republic of Ireland at the level of LAU 1.

In Ireland, usage of the word county nearly always comes before rather than after the county name; thus "County Roscommon" in Ireland as opposed to "Roscommon County" in Michigan, United States. The former "King's County" and "Queen's County" were exceptions; these are now County Offaly and County Laois, respectively. The abbreviation Co. is used, as in "Co. Roscommon". A further exception occurs in the case of those counties created after 1994 which often drop the word county entirely, or use it after the name; thus for example internet search engines show many more uses (on Irish sites) of "Fingal" than of either "County Fingal" or "Fingal County". There appears to be no official guidance in the matter, as even the local council uses all three forms.[2] In informal use, the word county is often dropped except where necessary to distinguish between county and town or city; thus "Offaly" rather than "County Offaly", but "County Antrim" to distinguish it from Antrim town. The synonym shire is not used for Irish counties, although the Marquessate of Downshire was named in 1789 after County Down.[nb 1]

Parts of some towns and cities were exempt from the jurisdiction of the counties that surrounded them. These towns and cities had the status of a County corporate, many granted by Royal Charter, which had all the judicial, administrative and revenue raising powers of the regular counties.

History

Pre-Norman divisions of Ireland

The political geography of Ireland can be traced with some accuracy from the 6th century. At that time Ireland was divided into a patchwork of petty kingdoms with a fluid political hierarchy which, in general, had three traditional grades of king. The lowest level of political control existed at the level of the túath (pl. túatha). A túath was an autonomous group of people of independent political jurisdiction under a rí túaithe, that is, a local petty king.[4] About 150 such units of government existed. Each rí túaithe was in turn subject to a regional or "over-king" (Irish: ruiri). There may have been as many as 20 genuine ruiri in Ireland at any time.

A "king of over-kings" (Irish: rí ruirech) was often a provincial (Irish: rí cóicid) or semi-provincial king to whom several ruiri were subordinate. No more than six genuine rí ruirech were ever contemporary. Usually, only five such "king of over-kings" existed contemporaneously and so are described in the Irish annals as fifths (Irish: cúigí). The areas under the control of these kings were: Ulster (Irish: Ulaidh), Leinster (Irish: Laighin), Connacht (Irish: Connachta), Munster (Irish: An Mhumhan) and Mide (Irish: An Mhídhe). Later record-makers dubbed them provinces, in imitation of Roman provinces. In the Norman period, the historic fifths of Leinster and Meath gradually merged, mainly due to the impact of the Pale, which straddled both, thereby forming the present-day province of Leinster.

The use of provinces as divisions of political power was supplanted by the system of counties after the Norman invasion. In modern times clusters of counties have been attributed to certain provinces but these clusters have no legal status. They are today seen mainly in a sporting context, as Ireland's four professional rugby teams play under the names of the provinces, and the Gaelic Athletic Association has separate Provincial councils and Provincial championships.

Plantagenet era

Lordships

With the arrival of Cambro-Norman knights in 1169, the Norman invasion of Ireland commenced. This was followed in 1172 by the invasion of King Henry II of England, commencing English royal involvement.[nb 2]

After his intervention in Ireland, Henry II effectively divided the English colony into liberties also known as lordships. These were effectively palatine counties and differed from ordinary counties in that they were disjoined from the crown and that whoever they were granted to essentially had the same authority as the king and that the king's writ had no effect except a writ of error.[5] This covered all land within the county that was not church land.[5] The reasons for the creating of such powerful entities in Ireland was due to the lack of authority the English crown had there.[5] The same process occurred after the Norman conquest of England where despite there being a strong central government, county palatines were needed in border areas with Wales and Scotland.[5] In Ireland this meant that the land was divided and granted to Richard de Clare and his followers who became lords (and sometimes called earls), with the only land which the English crown had any direct control over being the sea-coast towns and territories immediately adjacent.[5]

Of Henry II's grants, at least three of them—Leinster to Richard de Clare; Meath to Walter de Lacy; Ulster to John de Courcy—were equivalent to palatine counties in their bestowing of royal jurisdiction to the grantees.[5] Other grants include the liberties of Connaught and Tipperary.[5]

Division of lordships

These initial lordships were later subdivided into smaller "liberties", which appear to have enjoyed the same privileges as their predecessors.[5] The division of Leinster and Munster into smaller counties is commonly attributed to King John, mostly due to lack of prior documentary evidence, which has been destroyed. However, they may have had an earlier origin.[5] These counties were: in Leinster: Carlow (also known as Catherlogh), Dublin, Kildare, Kilkenny, Louth (also known as Uriel), Meath, Wexford, Waterford; in Munster: Cork, Limerick, Kerry and Tipperary.[5] It is thought that these counties did not have the administrative purpose later attached to them until late in the reign of King John, and that no new counties were created until the Tudor dynasty.[5]

The most important office in those that were palatine was that of seneschal.[5] In those liberties that came under Crown control this office was held by a sheriff.[5] The sovereign could and did appoint sheriffs in palatines; however, their power was confined to the church lands, and they became known as sheriffs of a County of the Cross, of which there seem to have been as many in Ireland as there were counties palatine.[5]

The exact boundaries of the liberties and shrievalties appears to have been in constant flux throughout the Plantagenet period, seemingly in line with the extent of English control.[5] For example, in 1297 it is recorded that Kildare had extended to include the lands that now comprise the modern-day counties of Offaly, Laois (Leix) and Wicklow (Arklow).[5] Some attempts had also been made to extend the county system to Ulster.[5]

However the Bruce Invasion of Ireland in 1315 resulted in the collapse of effective English rule in Ireland, with the land controlled by the crown continually shrinking to encompass Dublin, and parts of Meath, Louth and Kildare.[5] Throughout the rest of Ireland, English rule was upheld by the earls of Desmond, Ormond, and Kildare (all created in the 14th-century), with the extension of the county system all but impossible.[5] During the reign of Edward III (1327–77) all franchises, grants and liberties had been temporarily revoked with power passed to the king's sheriffs over the seneschals.[5] This may have been due to the disorganisation caused by the Bruce invasion as well as the renouncing of the Connaught Burkes of their allegiance to the crown.[5]

The Earls of Ulster divided their territory up into counties; however, these are not considered part of the Crown's shiring of Ireland. In 1333, the Earldom of Ulster is recorded as consisting of seven counties: Antrim, Blathewyc, Cragferus, Coulrath, del Art, Dun (also known as Ladcathel), and Twescard.[6][7]

Passage to the Crown

Of the original lordships or palatine counties:

- Leinster had passed from Richard de Clare to his daughter, Isabel de Clare, who had married William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke (second creation of title). This marriage was confirmed by King John, with Isabel's lands given to William as consort. The liberty was afterwards divided into five—Carlow, Kildare, Kilkenny, Leix and Wexford—one for each of Marshal's co-heiresses.[5]

- Meath was divided between the granddaughters of Walter de Lacy: Maud and Margery. Maud's half became the liberty of Trim, and she married Geoffrey de Geneville. Margery's half retained the name Meath, and she married John de Verdon. After the marriage of Maud's daughter Joan to Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March, Trim later passed via their descendants to the English Crown. Meath, which had passed to the Talbots, was resumed by Henry VIII under the Statute of Absentees.[5]

- Ulster was regranted to the de Lacys from John de Courcy, whilst Connaught, which had been granted to William de Burgh, was at some point divided into the liberties of Connaught and Roscommon. William's grandson Walter de Burgh was in 1264 also made lord of Ulster, bringing both Connaught and Ulster under the same lord. In 1352 Elizabeth de Burgh, 4th Countess of Ulster married Lionel of Antwerp, a son of king Edward III. Their daughter Philippa married Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March. Upon the death of Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March in 1425, both lordships were inherited by Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York and thus passed to the Crown.[5]

- Tipperary was resumed by King James I, however under Charles II in 1662 was reconstituted for James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde.[5]

With the passing of liberties to the Crown, the number of Counties of the Cross declined, and only one, Tipperary, survived into the Stuart era; the others had ceased to exist by the reign of Henry VIII.[5]

Tudor era

It was not until the Tudors, specifically the reign of Henry VIII (1509–47), that crown control started to once again extend throughout Ireland.[5] Having declared himself King of Ireland in 1541, Henry VIII went about converting Irish chiefs into feudal subjects of the crown with land divided into districts, which were eventually amalgamated into the modern counties.[5] County boundaries were still ill-defined; however, in 1543 Meath was split into Meath and Westmeath.[5] Around 1545, the Byrnes and O'Tooles, both native septs who had constantly been a pain for the English administration of the Pale, petitioned the Lord Deputy of Ireland to turn their district into its own county, Wicklow, however this was ignored.[5]

During the reigns of the last two Tudor monarchs, Mary I (1553–58) and Elizabeth I (1568–1603), the majority of the work for the foundation of the modern counties was carried out under the auspices of three Lord Deputies: Thomas Radclyffe, 3rd Earl of Sussex, Sir Henry Sydney, and Sir John Perrot.[5]

Mary's reign saw the first addition of actual new counties since the reign of King John. Radclyffe had conquered the districts of Glenmaliry, Irry, Leix, Offaly, and Slewmargy from the O'Moores and O'Connors, and in 1556 a statute decreed that Offaly and part of Glenmaliry would be made into the county of King's County, whilst the rest of Glenmarliry along with Irry, Leix and Slewmargy was formed into Queen's County.[5] Radclyffe brought forth legislation to shire all land as yet unshired throughout Ireland and sought to divide the island into six parts—Connaught, Leinster, Meath, Nether Munster, Ulster, and Upper Munster. However, his administrative reign in Ireland was cut short, and it was not until the reign of Mary's successor, Elizabeth, that this legislation was re-adopted. Under Elizabeth, Radclyffe was brought back to implement it.[5]

Sydney during his three tenures as Lord Deputy created two presidencies to administer Connaught and Munster. He shired Connaught into the counties of Galway, Mayo, Roscommon, and Sligo.[5] In 1565 the territory of the O'Rourkes within Roscommon was made into the county of Leitrim. In an attempt to reduce the importance of the province of Munster, Sydney, using the River Shannon as a natural boundary took the former kingdom of Thomond (North Munster) and made it into the county of Clare as part of the presidency of Connaught in 1569.[5] A commission headed by Perrot and others in 1571 declared that the territory of Desmond in Munster was to be made a county of itself, and it had its own sheriff appointed, however in 1606 it was merged with the county of Kerry.[5] In 1575 Sydney made an expedition to Ulster to plan its shiring. However, nothing came to bear.[5]

In 1578 the go-ahead was given for turning the districts of the Byrnes and O'Tooles into the county of Wicklow. However, with the outbreak of war in Munster and then Ulster, they resumed their independence.[5] Sydney also sought to split Wexford into two smaller counties, the northern half of which was to be called Ferns, but the matter was dropped as it was considered impossible to properly administer.[5] The territory of the O'Farrells of Annaly, however, which was in Westmeath, in 1583 was formed into the county of Longford and transferred to Connaught.[5][8] The Desmond rebellion (1579–83) that was taking place in Munster stopped Sydney's work and by the time it had been defeated Sir John Perrot was now Lord Deputy, being appointed in 1584.[5]

Perrot would be most remembered for shiring the only province of Ireland that remained effectively outside of English control, that of Ulster.[5] Prior to his tenancy the only proper county in Ulster was Louth, which had been part of the Pale.[5] There were two other long recognised entities north of Louth—Antrim and Down—that had at one time been "counties" of the Earldom of Ulster and were regarded as apart from the unreformed parts of the province.[5] The date Antrim and Down became constituted is unknown.[5] Perrot was recalled in 1588 and the shiring of Ulster would for two decades basically exist on paper as the territory affected remained firmly outside of English control until the defeat of Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone in the Nine Years' War.[5] These counties were: Armagh, Cavan, Coleraine, Donegal, Fermanagh, Monaghan, and Tyrone.[5] Cavan was formed from the territory of the O'Reilly's of East Breifne in 1584 and had been transferred from Connaught to Ulster.[9] After O'Neill and his allies fled Ireland in 1607 in the Flight of the Earls, their lands became escheated to the Crown and the county divisions designed by Perrot were used as the basis for the grants of the subsequent Plantation of Ulster effected by King James I, which officially started in 1609.[5]

Around 1600 near the end of Elizabeth's reign, Clare was made an entirely distinct presidency of its own under the Earls of Thomond and would not return to being part of Munster until after the Restoration in 1660.[5]

It was not until the subjugation of the Byrnes and O'Tooles by Lord Deputy Sir Arthur Chichester that in 1606 Wicklow was finally shired.[5] This county was one of the last to be created, yet was the closest to the center of English power in Ireland.[5]

County Londonderry was incorporated in 1613 by the merger of County Coleraine with the barony of Loughinsholin (in County Tyrone), the North West Liberties of Londonderry (in County Donegal), and the North East Liberties of Coleraine (in County Antrim).

Demarcation of counties and Tipperary

Throughout the Elizabethan era and the reign of her successor James I, the exact boundaries of the provinces and the counties they consisted of remained uncertain. In 1598 Meath is considered a province in Hayne's Description of Ireland, and included the counties of Cavan, East Meath, Longford, and Westmeath.[5] This contrasts to George Carew's 1602 survey where there were only four provinces with Longford part of Connaught and Cavan not mentioned at all with only three counties mentioned for Ulster.[5] During Perrot's tenure as Lord President of Munster before he became Lord Deputy, Munster contained as many as eight counties rather than the six it later consisted of.[5] These eight counties were: the five English counties of Cork, Limerick, Kerry, Tipperary, and Waterford; and the three Irish counties of Desmond, Ormond, and Thomond.[5]

Perrot's divisions in Ulster were for the main confirmed by a series of inquisitions between 1606 and 1610 that settled the demarcation of the counties of Connaught and Ulster.[5] John Speed's Description of the Kingdom of Ireland in 1610 showed that there was still a vagueness over what counties constituted the provinces, however Meath was no longer reckoned a province.[5] By 1616 when the Attorney General for Ireland Sir John Davies departed Ireland, almost all counties had been delimited.[5] The only exception was the county of Tipperary, which still belonged to the palatinate of Ormond.[5]

Tipperary would remain an anomaly being in effect two counties, one palatine, the other of the Cross until 1715 during the reign of King George I where an act abolished the "royalties and liberties of the County of Tipperary" and "that whatsoever hath been denominated or called Tipperary or Cross Tipperary, shall henceforth be and remain one county for ever, under the name of the County of Tipperary."[5]

Sub-divisions of counties

To correspond with the subdivisions of the English shires into honours or baronies, Irish counties were granted out to the Anglo-Norman noblemen in cantreds, later known as baronies, which in turn were subdivided, as in England, into parishes. Parishes were composed of townlands. However, in many cases, these divisions correspond to earlier, pre-Norman, divisions. While there are 331[10] baronies in Ireland, and more than a thousand civil parishes, there are around sixty thousand townlands that range in size from one to several thousand hectares. Townlands were often traditionally divided into smaller units called quarters, but these subdivisions are not legally defined.

Counties corporate

The following towns/cities had charters specifically granting them the status of a county corporate:

- County of the Town of Carrickfergus (by 1325)

- County of the City of Cork (1608)

- County of the Town of Drogheda (1412)

- County of the City of Dublin (1548)

- County of the Town of Galway (1610)

- County of the City of Kilkenny (1610)

- County of the City of Limerick (1609)

- County of the City of Waterford (1574)

The only entirely new counties created in 1898 were the county boroughs of Londonderry and Belfast. Carrickfergus, Drogheda and Kilkenny were abolished; Galway was also abolished, but recreated in 1986.

Exceptions to the county system of control

Regional presidencies of Connacht and Munster remained in existence until 1672, with special powers over their subsidiary counties. Tipperary remained a county palatine until the passing of the County Palatine of Tipperary Act 1715, with different officials and procedures from other counties. At the same time, Dublin, until the 19th century, had ecclesiastical liberties with rules outside those applying to the rest of Dublin city and county. Exclaves of the county of Dublin existed in counties Kildare and Wicklow. At least eight other enclaves of one county inside another, or between two others, existed. The various enclaves and exclaves were merged into neighbouring and surrounding counties, primarily in the mid-19th century under a series of Orders in Council.

Evolution of functions

The Church of Ireland exercised functions at the level of civil parish that would later be exercised by county authorities. Vestigial feudal power structures of major old estates remained well into the 18th century. Urban corporations operated individual royal charters. Management of counties came to be exercised by grand juries. Members of grand juries were the local payers of rates who historically held judicial functions, taking maintenance roles in regard to roads and bridges, and the collection of "county cess" taxes. They were usually composed of wealthy "country gentlemen" (i.e. landowners, farmers and merchants):

A country gentleman as a member of a Grand Jury...levied the local taxes, appointed the nephews of his old friends to collect them, and spent them when they were gathered in. He controlled the boards of guardians and appointed the dispensary doctors, regulated the diet of paupers, inflicted fines and administered the law at petty sessions.[11]

The counties were initially used for judicial purposes, but began to take on some governmental functions in the 17th century, notably with grand juries.

19th and 20th centuries

In 1836, the use of counties as local government units was further developed, with grand-jury powers extended under the Grand Jury (Ireland) Act 1836. The traditional county of Tipperary was split into two judicial counties (or ridings) following the establishment of assize courts in 1838. Also in that year, local poor law boards, with a mix of magistrates and elected "guardians" took over the health and social welfare functions of the grand juries.

Sixty years later, a more radical reorganisation of local government took place with the passage of the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898. This Act established a county council for each of the thirty-three Irish administrative counties. Elected county councils took over the powers of the grand juries. The boundaries of the traditional counties changed on a number of occasions. The 1898 Act changed the boundaries of Counties Galway, Clare, Mayo, Roscommon, Sligo, Waterford, Kilkenny, Meath and Louth, and others. County Tipperary was divided into two regions: North Riding and South Riding. Areas of the cities of Belfast, Cork, Dublin, Limerick, Derry and Waterford were carved from their surrounding counties to become county boroughs in their own right and given powers equivalent to those of administrative counties.[12][13][14]

Under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, the island was partitioned between Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland. For the purposes of the Act,

... Northern Ireland shall consist of the parliamentary counties of Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone, and the parliamentary boroughs of Belfast and Londonderry, and Southern Ireland shall consist of so much of Ireland as is not comprised within the said parliamentary counties and boroughs.[15]

The county and county borough borders were thus used to determine the line of partition. Southern Ireland shortly afterwards became the Irish Free State. This partition was entrenched in the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which was ratified in 1922, by which the Irish Free State left the United Kingdom with Northern Ireland making the decision to not separate two days later.

Under the Local Government Provisional Order Confirmation Act 1976, part of the urban area of Drogheda, which lay in County Meath, was transferred to County Louth on 1 January 1977. This resulted in the land area of County Louth increasing slightly at the expense of County Meath.[16] The possibility of a similar action with regard to Waterford City has been raised in recent years, though opposition from Kilkenny has been strong.

Historical and traditional counties

Areas that were shired by 1607 and continued as counties until the local government reforms of 1836, 1898 and 2001 are sometimes referred to as "traditional" or "historic" counties. These were distinct from the counties corporate that existed in some of the larger towns and cities, although linked to the county at large for other purposes. From 1898 to 2001, areas with county councils were known as administrative counties, while the counties corporate were designated as county boroughs. In other cases, the "traditional" county was divided to form two administrative counties. From 2001, certain administrative counties, which were originally "traditional" counties, underwent further splitting.

Current usage

In the Republic of Ireland

|

|---|

In the Republic of Ireland the traditional counties are, in general, the basis for local government, planning and community development purposes, are governed by county councils and are still generally respected for other purposes. Administrative borders have been altered to allocate various towns exclusively into one county having been originally split between two counties.

There are now 26 county councils, three city councils, and two city and county councils – a total of 31 local government areas.

County Tipperary was split into North and South Ridings in 1838. These Ridings were established as separate administrative counties under the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898. The Local Government Reform Act 2014 abolished North Tipperary and South Tipperary, and re-established County Tipperary.

County Dublin was abolished as an administrative county in 1994, while also remaining a point of reference for purposes other than local government. Its territory was divided into three administrative counties: Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Fingal, and South Dublin. The county borough of Dublin, together with the county boroughs of Cork, Galway, Limerick and Waterford, were re-styled as city councils under the Local Government Act 2001, with the same status in law as county councils.

The city councils of Limerick and Waterford were merged with their respective county councils by the Local Government Reform Act 2014, to form new city and county councils. The city of Kilkenny does not have a "city council" as it was a borough but not a county borough. It is now administered by its eponymous county council but is, exceptionally, permitted to retain the style of "city" for ornament only.

Of the administrative structures established under the 1898 Act, the only type to have been completely abolished was the Rural District, which was rendered void in the early years of the Irish Free State amidst widespread allegations of corruption. At a level above that of LAU is the Region which clusters counties together for NUTS purposes. The Regions are administered by Regional Authorities which were established by the Local Government Act 1991 and came into existence in 1994.

Education

In 2013 Education and Training Boards (ETBs) were formed throughout the Republic of Ireland, replacing the system of Vocational Education Committees (VECs) created in 1930. Originally, VECs were formed for each administrative county and county borough, and also in a number of larger towns. In 1997 the majority of town VECs were absorbed by the surrounding county. The 33 VEC areas were reduced to 16 ETB areas, with each consisting of one or more local government county or city.[17]

The Institute of technology system was organised on the committee areas or "functional areas", these still remain legal but are not as important as originally envisioned as the institutes are now more national in character and are only really applied today when selecting governing councils, similarly Dublin Institute of Technology was originally a group of several colleges of the City of Dublin committee.

Elections

Where possible, Dáil constituencies follow county boundaries. Under the Electoral Act 1997, a Constituency Commission is established following the publication of census figures every five years. The Commission is charged with defining constituency boundaries, and the 1997 Act provides that the breaching of county boundaries shall be avoided as far as practicable.[18] This provision does not apply to the boundaries between cities and counties, or between the three counties in the Dublin area.

This system usually results in more populated counties having several constituencies: Dublin, including Dublin city, is subdivided into twelve constituencies, Cork into five. On the other hand, smaller counties such as Carlow and Kilkenny or Laois and Offaly may be paired to form constituencies. An extreme case is the splitting of Ireland's least populated county of Leitrim between the constituencies of Sligo–North Leitrim and Roscommon–South Leitrim.

Each county or city is divided into local electoral areas for the election of councillors. The boundaries of the areas and the number of councillors assigned are fixed from time to time by order of the Minister for Housing, Planning and Local Government, following a report by the Local Government Commission, and based on population changes recorded in the census.[19]

In Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, a major reorganisation of local government in 1973 replaced the six traditional counties and two county boroughs (Belfast and Derry[nb 3]) with 26 single-tier districts for local government purposes. In 2015, as a result of a reform process that started in 2005, these districts were merged to form 11 new single-tier "super districts".

The six traditional counties remain in use for some purposes, including the three-letter coding of vehicle number plates, the Royal Mail Postcode Address File (which records counties in all addresses although they are no longer required for postcoded mail) and Lord Lieutenancies (for which the former county boroughs are also used). There are no longer official 'county towns'. However the counties are still very widely acknowledged, for example as administrative divisions for sporting and cultural organisations.

Other uses

The administrative division of the island along the lines of the traditional 32 counties was also adopted by non-governmental and cultural organisations. In particular the Gaelic Athletic Association continues to organise its activities on the basis of GAA counties that, throughout the island, correspond almost exactly to the 32 traditional counties in use at the time of the foundation of that organisation in 1884. The GAA also uses the term "county" for some of its organisational units in Britain and further afield.

List of counties

The 35 divisions listed below include the ‘traditional’ counties of Ireland as well as those created or re-created after the 19th century. Twenty four counties still delimit the remit of local government divisions in the Republic of Ireland (in some cases with slightly redrawn boundaries). In Northern Ireland, the counties listed no longer serve this purpose. The Irish-language names of counties in the Republic of Ireland are prescribed by ministerial order, which in the case of three newer counties, omits the word contae (county).[20] Irish names form the basis for all English-language county names except Waterford, Wexford, and Wicklow, which are of Norse origin.

In the ’Region’ column of the table below, except for the six Northern Ireland counties the reference is to NUTS 3 statistical regions of the Republic of Ireland. ’County town’ is the current or former administrative capital of the county.

Cities which, in the Republic, are currently administered outside the county system, but with the same legal status as administrative counties, are not shown separately: these are Cork, Dublin and, Galway. Also omitted are the former county boroughs of Londonderry and Belfast which in Northern Ireland had the same legal status as the six counties until the reorganisation of local government in 1973. County Dublin, which was officially abolished in 1994, is included, as are the three new administrative counties which took over the functions of the defunct Dublin County Council.

| County | Native name (Irish)[21] | Ulster-Scots name(s) |

County town | Most populous city/town |

Province | Region | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antrim | Aontroim (Contae Aontroma) |

Anthrim[22] Antrìm[23] Entrim[24] |

Ballymena (formerly Carrickfergus 1850–1970) |

Belfast (part) | Ulster | Northern Ireland – UKN0 | ||

| Armagh | Ard Mhacha (Contae Ard Mhacha) |

Airmagh[25] | Armagh | Craigavon | Ulster | Northern Ireland – UKN0 | ||

| Carlow | Ceatharlach (Contae Cheatharlach) |

Carlow | Carlow | Leinster | South-East – IE024 | ‡ | ||

| Cavan | An Cabhán (Contae an Chabháin) |

Cavan | Cavan | Ulster | Border – IE011 | ‡ | ||

| Clare | An Clár (Contae an Chláir) |

Ennis | Ennis | Munster | Mid-West – IE023 | ‡ | ||

| Cork | Corcaigh (Contae Chorcaí) |

Coark[26] | Cork | Cork | Munster | South-West – IE025 | ||

| Donegal | Dún na nGall (Contae Dhún na nGall) |

Dinnygal Dunnygal[26] |

Lifford | Letterkenny | Ulster | Border – IE011 | ‡ | |

| Down | An Dún (Contae an Dúin) |

Doon Doun |

Downpatrick | Belfast (part) | Ulster | Northern Ireland – UKN0 | ||

| Dublin | Baile Átha Cliath (Contae Bhaile Átha Cliath) |

Dublin | Dublin | Leinster | Dublin – IE021 | |||

| Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown | Dún Laoghaire–Ráth an Dúin | Dún Laoghaire | Dún Laoghaire | Leinster | Dublin – IE021 | ‡ | ||

| Fingal | Fine Gall | Swords | Swords | Leinster | Dublin – IE021 | ‡ | ||

| South Dublin | Áth Cliath Theas | Tallaght | Tallaght | Leinster | Dublin – IE021 | ‡ | ||

| Fermanagh | Fear Manach (Contae Fhear Manach) |

Fermanay | Enniskillen | Enniskillen | Ulster | Northern Ireland – UKN0 | ||

| Galway | Gaillimh (Contae na Gaillimhe) |

Galway | Galway | Connacht | West – IE013 | |||

| Kerry | Ciarraí (Contae Chiarraí) |

Tralee | Tralee | Munster | South-West – IE025 | ‡ | ||

| Kildare | Cill Dara (Contae Chill Dara) |

Naas | Newbridge | Leinster | Mid-East – IE022 | ‡ | ||

| Kilkenny | Cill Chainnigh (Contae Chill Chainnigh) |

Kilkenny | Kilkenny | Leinster | South-East – IE024 | ‡ | ||

| Laois | Laois (Contae Laoise) |

Portlaoise | Portlaoise | Leinster | Midlands – IE012 | ‡ | ||

| Leitrim | Liatroim (Contae Liatroma) |

Carrick-on-Shannon | Carrick-on-Shannon | Connacht | Border – IE011 | ‡ | ||

| Limerick | Luimneach (Contae Luimnigh) |

Lïmerick[26] | Limerick | Limerick | Munster | Mid-West – IE023 | ||

| Londonderry[nb 3] | Doire (Contae Dhoire) |

Lunnonderrie | Coleraine | Derry[nb 3] | Ulster | Northern Ireland – UKN0 | ||

| Longford | An Longfort (Contae an Longfoirt) |

Langfurd[26] | Longford | Longford | Leinster | Midlands – IE012 | ‡ | |

| Louth | Lú (Contae Lú) |

Dundalk | Drogheda | Leinster | Mid-East – IE022 | ‡ | ||

| Mayo | Maigh Eo (Contae Mhaigh Eo) |

Castlebar | Castlebar | Connacht | West – IE013 | ‡ | ||

| Meath | An Mhí (Contae na Mí) |

Navan (formerly Trim) |

Navan | Leinster | Mid-East – IE022 | ‡ | ||

| Monaghan | Muineachán (Contae Mhuineacháin) |

Ronelann[27] | Monaghan | Monaghan | Ulster | Border – IE011 | ‡ | |

| Offaly | Uíbh Fhailí (Contae Uíbh Fhailí) |

Tullamore (formerly Philipstown) |

Tullamore | Leinster | Midlands – IE012 | ‡ | ||

| Roscommon | Ros Comáin (Contae Ros Comáin) |

Roscommon | Roscommon | Connacht | West – IE013 | ‡ | ||

| Sligo | Sligeach (Contae Shligigh) |

Sligo | Sligo | Connacht | Border – IE011 | ‡ | ||

| Tipperary | Tiobraid Árann (Contae Thiobraid Árann) |

Nenagh (formerly Clonmel & Cashel) |

Clonmel | Munster | ‡ | |||

| Tyrone | Tír Eoghain (Contae Thír Eoghain) |

Owenslann[27] | Omagh | Omagh | Ulster | Northern Ireland – UKN0 | ||

| Waterford | Port Láirge (Contae Phort Láirge) |

Wattèrford[26] | Waterford | Waterford | Munster | South-East – IE024 | ||

| Westmeath | An Iarmhí (Contae na hIarmhí) |

Mullingar | Athlone | Leinster | South-East – IE024 | ‡ | ||

| Wexford | Loch Garman (Contae Loch Garman) |

Wexford | Wexford | Leinster | South-East – IE024 | ‡ | ||

| Wicklow | Cill Mhantáin (Contae Chill Mhantáin) |

Wicklow | Bray | Leinster | Mid-East – IE022 | ‡ | ||

‡ Also administrative

See also

- Gaelic Athletic Association county

- History of Ireland

- History of the United Kingdom

- Vehicle registration plates of the Republic of Ireland

- Vehicle registration plates of Northern Ireland

- List of Irish counties by area

- List of Irish counties by population

- List of Irish counties' coats of arms

- List of Irish county towns

- ISO 3166-2:GB

- ISO 3166-2:IE

Notes

- ^ Irish county constituencies at Westminster were written Corkshire, Tipperaryshire, etc. in some official British publications between the Acts of Union 1800 and the Irish Reform Act 1832.[3]

- ^ Whilst often today called English, a term which would not have been understood at the time, Henry II was in fact a Norman Frenchman, born in Le Mans and spent most of his early life there. His accession, which was essentially by force from his mother's cousin Stephen, was the continuance of the Norman subjugation of England

- ^ a b c The city and county officially named Londonderry are often called Derry. See Derry/Londonderry name dispute.

References

- ^ Bryne, T., Local Government in Britain, (1994)

- ^ Fingal County Council website, where (apart from references to the Council itself) both "Fingal County" and "County Fingal" appear, but much less frequently than "Fingal" alone.

- ^ See:

- G. E. E. (June 1802). Urban, Sylvanus (ed.). "Letter on the Royal Kalendar 1802". The Gentleman's Magazine. 72. London: 513. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

I do not like innovation, unless improvement accompanies it. I see, therefore no improvement in now calling the counties of Ireland shires, not one of the 32 being called so in my time there; and it has an awkward sound to say Downshire, Corkshire, Londonderryshire, &c.

- "Reform Bill — Second Reading — Division list". Hansard. 17 December 1831. HC Deb vol 9 cc546–547. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help)

- G. E. E. (June 1802). Urban, Sylvanus (ed.). "Letter on the Royal Kalendar 1802". The Gentleman's Magazine. 72. London: 513. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Michael Richter, Medieval Ireland, Revised edition, Dublin 2005

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh Falkiner, Caesar Litton. The Counties of Ireland: An Historical Sketch of Their Origin, Constitution, and Gradual Delimitation. Royal Irish Academy.

- ^ Bardon, Jonathan: A History of Ulster, page 45. The Black Staff Press, 2005. ISBN 0-85640-764-X

- ^ Hughes and Hannan: Place-Names of Northern Ireland, Volume Two, County Down II, The Ards, The Queen's University of Belfast, 1992. ISBN 085389-450-7

- ^ John G. Crawford, Anglicising the Government of Ireland: The Irish Privy Council & the Expansion of Tudor Rule 1556–1578, Blackrock, 1993

- ^ Desmond Roche, Local Government in Ireland, Dublin, 1982

- ^ "2011 Census Boundaries". census.cso.ie. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ McDowell, R. B (1975). T.W. Moody; J.C. Beckett; J.V. Kelleher (eds.). The Church of Ireland, 1869–1969. Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. p. 2. ISBN 0 7100 8072 7. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ "Proposed Alterations in Counties". Irish Times. 19 July 1898. p. 7.

- ^ "Orders declaring the boundaries of administrative counties and defining county electoral divisions". 27th Report of the Local Government Board for Ireland (Cmd.9480). Dublin: HMSO. 1900. pp. 235–330.

- ^ A Handbook of Local Government in Ireland (1899) "containing an Explanatory Introduction to the Local Government (Ireland) Act, 1898: together with the Text of the Act, the Orders in Council, and the Rules made thereunder relating to County Council, Rural District Council, and Guardian's Elections. With an Index"

- ^ Government of Ireland Act 1920 -text

- ^ Tully, James (19 October 1976). "Local Government Provisional Order Confirmation Act, 1976". Office of the Irish Attorney General. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ^ "01 July, 2013– Education and Training Boards replace VECs". Department of Education and Skills. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ Electoral Act 1997

- ^ "Local Government Act 2001, Section 23". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ^ Ministerial Order, 2003 setting out Irish-language names

- ^ Gasaitéar na hÉireann / Gazetteer of Ireland. Dublin: Brainse Logainmneacha na Suirbhéireachta Ordanáis / Placenames Branch of the Ordnance Survey. 1989. ISBN 978-0-7076-0076-5.

- ^ "Yierly report 2008". Tourism Ireland. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Bonamargy Friary (Ulster-Scots Translation)" (PDF). Department of the Environment (Northern Ireland). Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "The Ulster-Scot, June 2011". Ulster-Scots Agency. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ North-South Ministerial Council: 2006 Annual Report in Ulster Scots Archived 27 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e North/South Ministerial Council. "Noarth/Sooth Cooncil o Männystèrs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Fair faa ye tae Rathgannon Sooth Owenslann Burgh Cooncil". Dungannon & South Tyrone Borough Council. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2017.